Abstract

Agriculture is central to Nepal’s economy but faces growing challenges such as environmental degradation, labor shortages, and the increasing feminization of farming due to male outmigration. Environmental Conservation Agriculture (ECA) offers a sustainable solution, yet adoption remains inconsistent due to knowledge gaps and resource constraints. This study examines the socio-demographic, economic, and environmental factors influencing the farmers’ willingness to learn about ECA and its relationship with women’s empowerment. A cross-sectional survey of 383 ECA farmers across the Kavre, Dhading, and Chitwan districts in Bagmati Province reveals that 72.6% are willing to learn about ECA, driven by climate change concerns, economic incentives, and market access. Farmers who have experienced climate-related crop losses (64%) and those engaged in consumer-driven markets (59%) show a greater inclination to learn ECA. Spearman correlation analysis highlights key factors influencing willingness to learn, including perceptions of ECA as a climate-resilient practice, interest in ECA, and awareness of FAO’s promotion of ECA. Farmers who believe that ECA enhances sustainability, resilience, and income are also more likely to engage, while market dissatisfaction presents a challenge. Receiving ECA subsidies is positively associated with willingness to learn, highlighting the role of financial support in adoption. Women play a crucial role in agriculture but face barriers such as household responsibilities (22%), lack of education and training (18%), and limited financial access (12%). Key motivators for their participation include capacity-building initiatives (48%), financial support (16%), and empowerment programs (5%). Notably, households where women participate in early decision-making are 19% more likely to express willingness to learn about ECA, and perceptions of ECA as empowering women are positively linked to willingness to learn. Addressing these barriers through targeted policies, institutional support, and market-based incentives is essential for fostering inclusive and sustainable agricultural development. This study provides actionable insights for strengthening ECA adoption, promoting gender equity, and enhancing Nepal’s climate resilience.

1. Introduction

Agriculture is a cornerstone of Nepal’s economy and cultural identity, employing approximately 67% of households and contributing 24% to the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [1]. Predominantly managed by small-scale farmers, the sector faces challenges such as low literacy rates, labor shortages, and environmental degradation [2]. The growing feminization of agriculture, driven by the outmigration of men and youth to urban areas or abroad, has increasingly placed women at the forefront of agricultural production. This demographic shift underscores the critical need for women’s empowerment and inclusion in sustainable agricultural practices to enhance the sector’s resilience and productivity [3].

Environmental Conservation Agriculture (ECA) provides a sustainable pathway for addressing these challenges. By promoting practices such as minimal soil disturbance, crop diversification, and environmentally friendly input use, ECA seeks to reduce adverse environmental impacts and enhance sustainability in agricultural systems. Furthermore, ECA aligns with Nepal’s goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2045 [4], offering potential for soil carbon sequestration, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and improved resource efficiency. Despite its benefits, engagement with and adoption of ECA remain inconsistent, largely due to knowledge gaps, limited resources, and systemic barriers. This study seeks to understand the socio-demographic, environmental, and economic factors influencing farmers’ willingness to learn about ECA. Additionally, it explores the role of ECA in empowering women who face unique challenges due to cultural norms, restricted access to resources, and limited decision-making authority. By investigating these interconnected themes in the districts of Kavre, Dhading, and Chitwan in Bagmati Province, this research aims to provide actionable insights for fostering inclusive and sustainable agricultural systems, supporting Nepal’s climate goals, and improving livelihoods and community resilience.

1.1. Environmental Conservation Agriculture in Nepal

Environmental Conservation Agriculture (ECA) is increasingly recognized as a transformative approach to sustainable farming, particularly in regions facing ecological and socio-economic pressures [5,6]. ECA is an innovative farming approach that merges traditional and modern practices to enhance sustainability, resilience, and climate adaptation. It emphasizes reducing chemical inputs, conserving water, improving soil health, and preserving local biodiversity while integrating principles of minimal soil disturbance, permanent soil cover, and crop rotation to promote long-term agricultural viability. These principles are especially critical in Nepal, where traditional farming systems are under strain due to soil degradation, climate change, and the overuse of high-input agricultural practices [7]. By adopting ECA, Nepalese farmers can mitigate these challenges while improving crop yields and ensuring food security.

Research indicates that ECA practices, such as crop rotation and organic matter management, can significantly enhance soil organic carbon levels, thereby improving soil health and fertility. A meta-analysis demonstrated that conservation agriculture could increase soil carbon sequestration, contributing to climate change mitigation [8]. Additionally, studies have shown that conservation agriculture practices can reduce greenhouse gas emissions, further highlighting ECA’s role in climate change mitigation [9]. A study from Japan also supports ECA’s potential to lower emissions, reinforcing its role in climate resilience strategies [10]. In regions such as the Ifugao Rice Terraces, where traditional farming practices already align closely with ECA principles, its adoption offers a viable strategy for maintaining delicate ecosystems while securing sustainable livelihoods for farmers [11].

Bagmati Province, one of Nepal’s seven provinces, plays a crucial role in the country’s agricultural sector. With its diverse agro-ecological zones ranging from the mid-hills to the fertile plains of Chitwan, the province supports a wide variety of crops, including cereals, vegetables, and fruits. However, the region faces significant environmental and agricultural challenges, such as soil erosion, deforestation, declining soil fertility, and the overuse of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. While some farmers and local organizations have started adopting ECA principles to counter these issues, large-scale implementation remains limited due to socio-economic constraints, lack of technical knowledge, and limited access to resources. Strengthening ECA adoption in Bagmati Province could enhance soil health, improve water management, and contribute to long-term agricultural sustainability, making it a critical focus area for research and policy interventions. The districts of Dhading, Kavre, and Chitwan in Nepal exemplify both the potential and challenges associated with implementing Environmental Conservation Agriculture (ECA). Dhading’s diverse topography supports a variety of crops; however, excessive use of pesticides and fertilizers has led to soil acidification and water contamination [12]. Similarly, Kavre, a major vegetable-producing district, faces significant soil erosion and declining water resources due to deforestation and unsustainable farming practices [13]. In Chitwan, located in the fertile Terai plains and serving as an agricultural hub for livestock and poultry farming, intensive agricultural practices have resulted in greenhouse gas emissions and soil nutrient depletion [14].

Research indicates that ECA practices, such as crop rotation and organic matter management, can significantly enhance soil organic carbon levels, thereby improving soil health and fertility [10]. However, socio-economic barriers, including issues related to land ownership, limited financial capital, and perceived risks of yield reductions, hinder widespread adoption of ECA practices among farmers in these regions [15]. Addressing these challenges through targeted interventions is crucial for promoting sustainable agriculture and improving livelihoods in these districts.

1.2. Women Farmers’ Involvement in ECA

Women are indispensable to agricultural production, performing tasks such as land preparation, sowing, harvesting, livestock management, and post-harvest processing. Across Asia, women contribute 50% to 90% of labor in rice fields [16]. In Nepal, the feminization of agriculture has further expanded women’s roles to include irrigation management, labor allocation, and input procurement as men migrate for work. Despite their critical contributions, women often face structural barriers, including limited access to resources and decision-making power, which hinder their full participation in sustainable practices like ECA.

Empowering women in agriculture is essential for achieving sustainability. Studies show that women’s involvement in decision-making improves agricultural productivity and resource management [17]. In Nepal, women’s roles in manure application, crop selection, and fertilizer decisions have increased over the last two decades [18]. However, transitioning to ECA often increases women’s labor, particularly for tasks like intercropping and reduced tillage. For example, Halbrendt et al. (2014) reported a 2.17% rise in women’s labor with intercropped crops [19]. Without active participation in adoption decisions, these additional labor demands can create long-term barriers to sustaining ECA practices.

Global initiatives such as the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [20] and sustainable development goals (SDGs) [21] prioritize gender equity in agriculture. Tools like the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) quantify progress, highlighting the need to address disparities that limit women’s empowerment [22]. Given that women disproportionately experience the effects of climate change due to limited access to resources, empowering them through ECA is vital for fostering resilience and sustainability.

1.3. Previous Studies That Investigated Farmers’ Willingness to Learn About ECA

Several studies have explored the factors influencing farmers’ willingness to learn about ECA, offering insights into the socio-economic, cultural, and informational elements that affect their engagement with sustainable practices [5,6,10,11]. Socio-economic factors such as age, education level, farm size, and income play significant roles in shaping farmers’ openness to learning. For example, a study conducted by Meijer et al. (2015) across sub-Saharan Africa found that younger farmers with higher education levels were more receptive to innovative agricultural techniques due to their greater exposure to new information and capacity to adapt [23]. Similarly, larger farm sizes and higher incomes provided farmers with the financial capital needed to invest in ECA technologies, further encouraging learning.

Access to agricultural extension services is another pivotal factor influencing learning. Studies have shown that farmers who regularly interact with extension agents and participate in training programs are more likely to adopt sustainable practices. For instance, Läpple and Van Rensburg (2011), in their study in Ireland, demonstrated that high-quality extension services enhanced farmers’ willingness to adopt ECA by improving their knowledge and reducing uncertainties [24]. This finding aligns with the experience of the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) [25], which has systematically provided extensive support measures for farmer training and skills development, emphasizing structured training programs and knowledge dissemination mechanisms to enhance farmers’ competencies in sustainable agricultural practices. Moreover, perceived benefits and risks associated with ECA also influence learning motivation. Knowler and Bradshaw (2007), in a global review spanning North America, South America, and Asia, found that farmers were more likely to engage with ECA when they recognized tangible benefits such as improved soil fertility, increased yields, and reduced input costs [26]. However, concerns about potential yield reductions or economic losses during the transition phase discouraged some farmers from participating.

Cultural and social influences also play a crucial role in shaping farmers’ learning behaviors. Peer influence and community norms significantly impact decision-making, as farmers are often encouraged by observing successful ECA practices among their peers. Baumgart-Getz et al. (2012), in their meta-analysis of studies in the United States, emphasized the role of strong social networks in facilitating knowledge sharing and providing support for adopting new farming methods [27]. These findings align with the principles of Social Learning Theory, which underscores the importance of observation, interaction, and community-level dynamics in the learning process.

Understanding these factors, including successful policy interventions such as those implemented through the European Union’s CAP, is essential for designing effective educational programs and interventions. By tailoring educational programs to address specific barriers and leveraging motivators, stakeholders can foster an enabling environment for farmers to learn and adopt sustainable practices. The integration of these findings into the study’s theoretical foundation further strengthens its framework for analyzing the dynamics of learning and empowerment in sustainable agriculture.

1.4. Theoretical Foundation

The theoretical foundation of this study is rooted in Social Learning Theory [28,29,30] and Empowerment Theory [31], both of which offer valuable insights into the dynamics of learning and women’s empowerment in ECA participation. Social Learning Theory explains how individuals acquire new knowledge and skills through observation, imitation, and interaction within their social contexts [30]. It highlights the significance of demonstration plots, peer networks, and extension services in enhancing farmers’ willingness to learn about ECA. When farmers observe the successful implementation of ECA and perceive its benefits, such as improved yields, reduced input costs, and better soil health, they are more motivated to engage. However, barriers such as limited access to resources and low literacy levels can hinder the learning process, underscoring the need for supportive and inclusive educational initiatives.

Empowerment Theory focuses on the processes through which individuals and communities gain control over their lives, access resources, and participate in decision-making [31]. This framework is particularly relevant for exploring the role of ECA in empowering women farmers, who often face structural barriers such as restricted access to land, credit, and education. Empowerment through ECA can enable women to take leadership roles in sustainable agriculture, enhancing their agency, improving productivity, and fostering resilience to climate change. Empowered women are also more likely to share knowledge within their networks, creating a ripple effect that benefits the broader community.

By integrating these two frameworks, this study connects the factors influencing farmers’ willingness to learn with the transformative potential of empowering women in agriculture. Social Learning Theory provides a lens for analyzing the mechanisms of knowledge acquisition, while Empowerment Theory addresses the structural and social changes required to ensure gender equity. Together, these frameworks guide the analysis of the study, ensuring that its findings contribute to inclusive and effective strategies for promoting sustainable agricultural development.

2. Study Area and Methods

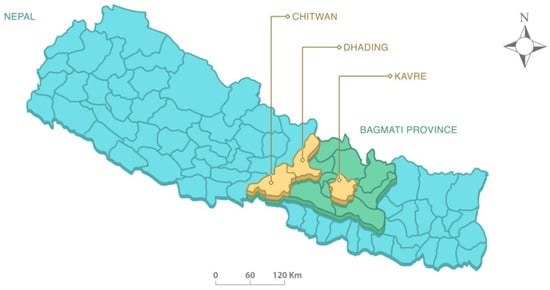

This study examines the factors influencing farmers’ willingness to learn about Environmental Conservation Agriculture (ECA) and the role of ECA in empowering women farmers. The research was conducted among 383 ECA farmers across three key districts in Bagmati Province, Nepal: Kavre, Dhading, and Chitwan. Bagmati Province is a significant agricultural region with diverse agro-ecological zones, ranging from the mid-hills to the fertile lowlands, making it a critical area for studying ECA adoption. While agriculture remains a primary livelihood source, challenges such as soil degradation, deforestation, excessive chemical use, and water scarcity threaten sustainability. Although ECA initiatives are growing in the region, adoption remains uneven due to socio-economic constraints and limited technical resources.

The selected study sites represent the province’s agro-ecological diversity. Kavre is a mid-hill district, and the surveyed area is in a montane region at higher altitudes, where temperate-zone farming practices are prevalent. Dhading, also a mid-hill to mountain district, has its survey area at lower altitudes, close to a highway, within the temperate zone. In contrast, Chitwan, located in the subtropical plains, serves as an agricultural hub with intensive farming systems. Together, these three districts capture distinct environmental conditions and farming practices within Bagmati Province, providing a comprehensive perspective on the challenges and opportunities associated with promoting sustainable farming practices and gender empowerment in agriculture (Figure 1). By focusing on these diverse agro-ecological zones, this study aims to contribute valuable insights into policy development and targeted interventions for scaling up ECA adoption and supporting women farmers in sustainable agriculture.

Figure 1.

Sampling sites of the study in Bagmati Province, Nepal.

Kavre District, situated in the mid-hills of Nepal, has a population of approximately 364,039 people as per the 2021 Nepal census. Known for its vegetable production, Kavre supplies fresh produce to the capital city, Kathmandu. Farmers in the district face challenges such as extreme weather events, water scarcity, and soil degradation, which have led to a dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Efforts to promote sustainable practices include initiatives by the Center for Environmental and Agricultural Policy Research, Extension, and Development (CEAPRED), which introduced organic solutions like “jholmal” as alternatives to chemical inputs. These initiatives provide a foundation for examining how ECA can enhance sustainable practices and empower women farmers in decision-making roles.

Dhading District, with a population of approximately 325,710, is characterized by its diverse topography, ranging from lowland areas to high hills, supporting a mix of subsistence farming, vegetable production, and agroforestry. The district has gained recognition for its commercial vegetable production, particularly in Dhunibesi Municipality, where pesticide use is prevalent. These conditions highlight the need for ECA to mitigate environmental and health risks while also offering an opportunity to study the factors that influence farmers’ willingness to learn about sustainable practices and women’s evolving roles in agriculture.

Chitwan District, located in the Terai plains and home to 719,859 people, is an agricultural hub for livestock and poultry production. With intensive farming practices, the district faces challenges such as soil nutrient depletion, greenhouse gas emissions, and environmental degradation. Chitwan also has a rapidly growing role for women in agriculture, driven by the outmigration of men. This makes the district an important site for exploring the intersection of ECA learning and women’s empowerment, particularly in the context of sustainable farming.

Data Collection and Analysis

This study employed a structured mixed-methods research model comprising several sequential and interrelated steps, clearly correlated with specific research methods:

- Step 1: Sampling and Site Selection

Primary data were collected using a multistage random sampling approach, ensuring representative selection of ECA-practicing farmers across three districts (Kavre, Dhading, and Chitwan). Slovin’s formula was applied to determine an appropriate sample size, resulting in the inclusion of a total of 383 farmers in the study. Study sites were chosen based on agricultural relevance and prevalence of ECA practices.

- Step 2: Survey Instrument Development and Data Acquisition

Data were acquired through face-to-face interviews using a semi-structured questionnaire designed explicitly for this research. The questionnaire captured detailed socio-demographic characteristics, agricultural practices, resource access, perceptions of climate change, willingness to adopt ECA, women’s involvement, and household decision-making dynamics. The survey instrument underwent pre-testing with 20 farmers in a neighboring district to ensure clarity, relevance, and reliability. Feedback from pre-testing was used to refine the questionnaire before final administration.

- Step 3: Field Data Collection

The survey was conducted over an eight-day period in February 2022 using KoboToolbox for digital data collection. Interviews were conducted by trained researchers, who received intensive training on ethical research practices, data quality management, informed consent procedures, and adherence to COVID-19 safety protocols. Ethical approval for the research procedures was secured from the Research Ethics Board of Hiroshima University.

- Step 4: Data Processing and Quantitative Analysis

The collected data were systematically cleaned and coded for analysis. Quantitative data analysis involved Spearman correlation to identify initial associations, followed by ordinal logistic regression modeling to determine significant drivers influencing farmers’ willingness to learn ECA. Principal component analysis (PCA), conducted with SPSS v.27 (IBM, New York, NY, USA), was used to identify latent factors related to women’s participation and decision-making roles.

- Step 5: Qualitative Analysis

To enrich the quantitative results, thematic analysis was conducted to explore qualitative data from open-ended survey responses, specifically identifying barriers and motivational factors influencing women’s participation in ECA practices.

- Step 6: Integration and Interpretation of Results

The final stage integrated insights from both quantitative (ordinal regression, PCA) and qualitative (thematic analysis) approaches. This provided a holistic understanding of the socio-demographic, institutional, and gender-related factors shaping ECA learning and empowerment.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and ECA-Related Data of the Nepalese Farmers

The study involving 383 ECA farmers provided insightful findings on the effects of climate change, farming adaptations, and perceptions of ecological and climate-adaptive ECA practices (Supplementary Table S1). With a near-equal distribution of females (50.7%) and males (49.3%), respondents represented various districts, predominantly from Kavre (40.2%), Dhading (38.6%), and Chitwan (21.1%). The age group most represented was 40–49 years (25.1%), followed by 30–39 years (21.7%), and 50–59 years (21.4%). Regarding caste/ethnicity, Bahuns comprised the majority (50.4%), followed by Janajatis (27.4%). Educational attainment showed that 39.9% had primary education, while 31.6% had secondary education, and only 4.7% had tertiary education. Farming experience was diverse, with the largest proportion (35.0%) having 10–20 years of experience.

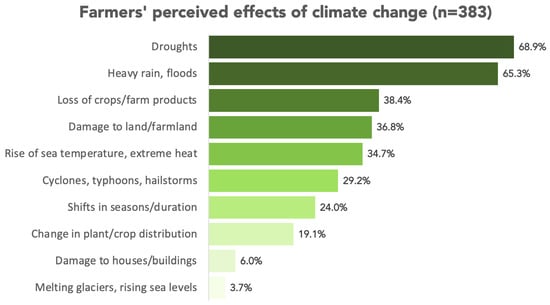

The majority of farmers (84.6%) reported their farming practices were affected by climate change (Figure 2), with drought being the most commonly cited impact (68.9%), followed by heavy rain and flooding (65.3%). Other reported effects included damage to crops or farm products (38.4%), damage to farmland (36.8%), and extreme heat days (34.7%). A smaller proportion of farmers cited changes in seasonal duration (24.0%), cyclones and hailstorms (29.2%), and changes in crop distribution (19.1%). Less frequently mentioned were damage to houses or buildings (6.0%) and melting glaciers or sea-level rise (3.7%).

Figure 2.

Perceived effects of climate change among ECA farmers in Bagmati Province, Nepal.

To adapt to these changes, farmers implemented various strategies. Improved pest and disease management (54.6%) and adjustments to planting times or seasons (48.6%) were the most common measures. Other adaptations included planting high-yielding crops (30.5%) or drought-tolerant varieties (25.3%), selecting alternative crops (30.5%), and managing soil nutrients (24.3%). Less frequent strategies involved improved water management (13.8%), changes in land use patterns such as crop diversification (6.5%), and technological adjustments like the use of ICT tools (6.0%). Market-related adaptations, such as insurance or market exchange initiatives, were the least reported (5.2%).

Farmers primarily sold their ECA products through middlemen or traders (70.8%) and local markets or periodic open markets (42.6%). Direct-to-consumer sales accounted for 26.4%, while 25.1% of products were reserved for self-consumption. Cooperatives (5.5%), processors or millers (8.6%), and restaurants or hotels (3.7%) were less frequently utilized, with supermarkets being the least reported sales channel (1.0%). Dissatisfaction with the prices of ECA products was high, with 83.8% of farmers expressing dissatisfaction.

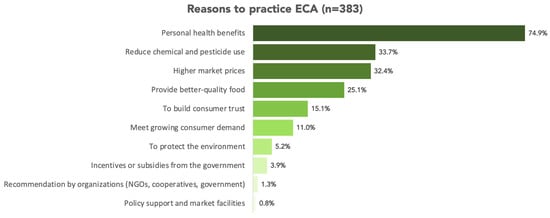

The adoption of ECA practices was driven by multiple factors (Figure 3), with self-health benefits being the most significant motivator (74.9%), followed by expectations of reduced costs of chemicals and pesticides (33.7%) and better prices for products (32.4%). Other motivators included the desire to supply better food to consumers (25.1%), meet growing consumer demand (11.0%), and build trust with consumers (15.1%). External recommendations, such as those from NGOs (1.3%) or government incentives and subsidies (3.9%), were less influential.

Figure 3.

Reasons to practice among ECA farmers in Bagmati Province, Nepal.

Farmers expected ECA to yield benefits such as increased agricultural income (44.6%), reduced climate hazards (33.4%), and contributions to agro-biodiversity conservation (22.7%), water quality improvement (22.5%), and groundwater conservation (22.5%). Other expectations included enhancing the quality of agricultural products (20.6%), mitigating climate change (18.5%), and promoting local industries (16.2%).

The perceived benefits of switching to ECA included health improvements (68.7%) and the potential for higher prices (45.2%). Other reasons were reducing the cost of chemicals and pesticides (27.9%), supplying better-quality food (29.2%), and meeting growing demand (15.9%). Farmers also believed ECA could build trust with consumers (11.0%), improve the local and global environment (4.2%), and enhance sustainability. However, awareness of FAO’s promotion of ECA was limited, with 62.1% of participants being unaware of such efforts.

Overall, these findings underscore the significant challenges farmers face due to climate change and their varied responses to these challenges. While interest in ECA practices is high, barriers such as market access, price dissatisfaction, and limited policy support highlight the need for targeted interventions to enhance ECA adoption, build resilience, and ensure sustainable farming practices.

3.2. Women’s Participation in ECA

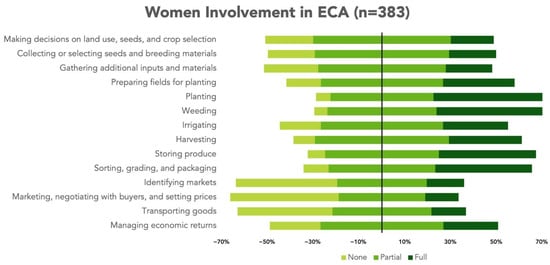

The findings highlight significant insights into women’s involvement, decision-making, and access and control in ecological and climate-adaptive (ECA) practices (Supplementary Table S2). Women’s participation varied across different activities, with full participation reported in specific areas but generally showing a trend of partial involvement dominating most tasks.

In terms of involvement, full participation was highest in planting (48.6%) and weeding (46.5%), followed by storing produce (42.6%) and sorting, grading, and packaging (42.3%) (Figure 2). Activities like harvesting (31.9%) and preparing fields for planting (31.3%) also saw relatively high levels of full involvement. However, decision-making on land use, seeds, and crop selection saw only 18.8% full participation, with the majority (60.3%) having partial involvement. Similarly, identifying markets (16.4%), marketing and negotiating with buyers (14.6%), and transporting goods (15.1%) saw lower levels of full participation, reflecting a gender gap in tasks linked to economic activities and market interactions.

The diverging stacked bar chart (Figure 4) provides a clear visual representation of these patterns. The chart is structured with full involvement on the positive side, no involvement on the negative side, and partial involvement in the middle. A vertical line at the center serves as a reference point, dividing positive and negative responses. This format allows for an easy comparison of women’s participation across different activities, revealing both their strong presence in farm labor and their limited engagement in decision-making and market-related roles.

Figure 4.

Women’s involvement in ECA.

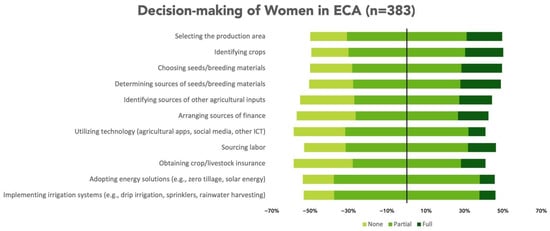

In decision-making, women exhibited higher partial participation across most activities (Figure 5). Selecting the production area and identifying crops saw partial participation levels of 62.4% and 60.8%, respectively, while choosing seeds or breeding materials showed 56.9% partial involvement. Decisions related to adopting energy solutions and implementing irrigation systems were also largely led by partial participation (76.0% and 75.7%, respectively). Full participation remained limited in most areas, with the highest being in choosing seeds and determining sources of breeding materials (21.1%). Decisions involving technology use, sourcing labor, and arranging finances saw even lower full involvement (8.9%, 14.6%, and 15.9%, respectively).

Figure 5.

Decision-making of women in ECA.

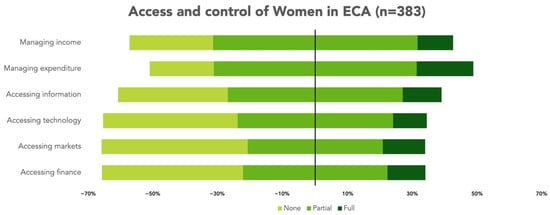

Access and control over resources and opportunities further reflected disparities (Figure 6). Partial access was most prominent, particularly in managing income (63.2%), managing expenditure (62.7%), and accessing information (54.0%). Full control was notably low, with the highest reported in managing expenditure (17.5%) and accessing markets (13.1%). The women’s access to technology (10.4%) and finances (11.7%) was particularly limited, with none reporting full access in critical areas such as agricultural innovation and funding.

Figure 6.

Access and control of women in ECA.

These findings suggest that while women play a significant role in various aspects of ECA practices, particularly in production-related tasks, their participation and decision-making are often restricted to partial involvement. Economic and market-related activities, as well as access to resources like technology and finance, remain areas where women face significant barriers. Addressing these gaps through targeted policies, capacity-building initiatives, and support systems is essential to enhancing women’s agency and contributions to sustainable agricultural practices.

3.3. Key Barriers and Motivations of Women’s Participation in ECA

This section explores the top barriers and motivations that women face in their participation in Environmental Conservation Agriculture (ECA). Based on responses from 383 farmers, these factors reveal the challenges and opportunities influencing women’s active involvement in sustainable agricultural practices. The key barriers faced by women in ECA can be classified into three main categories: socio-cultural barriers, resource and knowledge deficits, and institutional and structural challenges. These interconnected obstacles significantly limit women’s participation in ECA initiatives. Socio-cultural barriers emerged as the most significant, accounting for 42% of the responses. A notable 22% of farmers emphasized household responsibilities, highlighting how domestic chores disproportionately occupy women’s time and leave little opportunity for their participation in ECA activities. Male-dominated societal structures and a lack of freedom were identified by 12% of respondents as major challenges, reflecting deeply ingrained gender biases that restrict women’s mobility, decision-making power, and opportunities for collaboration. Additionally, 8% of farmers pointed out that women often prefer traditional agricultural methods, likely due to cultural norms or resistance to adopting new practices.

Resource and knowledge deficits constituted 37% of the identified barriers. Among these, a lack of education, training, and knowledge was cited by 18% of respondents as a critical obstacle that limits women’s ability to understand and implement innovative ECA practices. Insufficient access to resources such as financial capital, technology, and irrigation systems was highlighted by 12%, while another 7% mentioned limited access to information about sustainable agriculture. These deficits underscore the urgent need for initiatives that address both the technical and material gaps preventing women from effectively engaging in ECA. Institutional and structural challenges made up the remaining 21% of barriers. Within this category, 10% of respondents identified a lack of family and institutional support, including insufficient incentives and limited assistance from local bodies, as a significant challenge. Market access and infrastructure gaps, such as inadequate irrigation systems and delays in obtaining agricultural inputs like seeds and fertilizers, were cited by 7%. Additionally, 4% of farmers highlighted women’s low decision-making power in family and community settings as a major hindrance. These findings illustrate how systemic weaknesses further exacerbate the challenges faced by women in accessing and benefiting from sustainable agricultural programs [32,33].

In contrast to the barriers, the analysis also identified three major categories of motivating factors for women’s involvement in ECA: capacity building and knowledge development, support systems and incentives, and empowerment and motivation. Capacity building and knowledge development emerged as the most significant motivator, encompassing 48% of responses. Farmers repeatedly emphasized the importance of equipping women with the necessary skills and knowledge through initiatives such as training programs (18%), education opportunities (12%), awareness campaigns (10%), and exposure visits (8%). These activities were identified as critical for empowering women to participate actively and effectively in ECA. Respondents stressed the value of organized training sessions and awareness campaigns focused on sustainable farming practices and environmentally friendly techniques.

Support systems and incentives accounted for 38% of the motivating factors. Financial assistance and subsidies were highlighted by 16% of farmers as essential to reducing the financial burden associated with agricultural inputs like seeds, fertilizers, and technology. Access to markets and fair pricing mechanisms were identified by 12% as crucial for ensuring the economic viability of women engaged in agriculture. Additionally, family and community support (6%) and the availability of resources such as irrigation facilities and modern tools (4%) were noted as important motivators. These findings emphasize the necessity of providing comprehensive support systems to sustain women’s participation in ECA [34].

Empowerment and motivation represented the final category of motivating factors, making up 14% of responses. Farmers identified women’s empowerment programs (5%) as vital for fostering independence, respect, and leadership opportunities in agriculture. Recognition of women’s achievements (5%) was also seen as a key motivator, as it helps build women’s confidence and sense of agency. Furthermore, involving women in decision-making processes at both household and community levels (4%) was highlighted as an important factor in enhancing their participation. This category underscores the deeper social and cultural dimensions of women’s involvement in ECA, emphasizing the need to recognize and include women as equal contributors to agricultural and environmental sustainability.

3.4. Exploratory Factor Analysis of Variables Related to Women’s Engagement in ECA

The factor analysis reveals three distinct themes illustrating how women engage in various stages of ECA (Table 1). The first theme, “Core Production and Post-Harvest Activities”, covers tasks from preparing fields for planting through sorting, grading, and packaging, highlighting women’s significant involvement in field preparation, planting, weeding, irrigating, harvesting, and storing produce. The second theme, “Value Chain and Economic Gains”, encompasses sorting, grading, and packaging through managing economic returns, underscoring women’s role in identifying markets, negotiating with buyers, setting prices, transporting goods, and ultimately securing economic benefits. Lastly, the third theme, “Early-Stage Planning and Resource Mobilization”, groups tasks from making decisions on land use, seeds, and crop selection through gathering additional inputs and materials, reflecting women’s involvement in the foundational stages of agricultural production. Taken together, these findings indicate that women participate across all phases of ECA—from the initial decision on what and how to plant, to managing production, to marketing and revenue management. Recognizing and supporting these multifaceted roles carries important implications for policy and program interventions, as it highlights women’s contributions to both on-farm work and strategic, market-oriented decisions [35]. By addressing their needs and acknowledging the breadth of their involvement, efforts to enhance productivity, economic returns, and the overall sustainability of ECA can be more effectively realized [36].

Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis a of the 14 variables related to women’s involvement in ECA in Chitwan, Dhading, and Kavre districts at Bagmati Province, Nepal.

A second factor analysis of women’s decision-making, and their access to and control over resources, reveals four distinct themes (Table 2). The first theme, “Foundational Planning and Financing”, centers on selecting the production area, identifying crops, choosing seeds/breeding materials, determining sources of seeds/breeding materials, identifying sources of other agricultural inputs, and arranging sources of finance, indicating women’s involvement in essential early-stage decisions. The second theme, “Innovative and Risk Management Practices”, highlights the use of technology (e.g., agricultural apps and other ICT), sourcing labor, obtaining crop/livestock insurance, and adopting energy solutions and irrigation systems. Here, women’s decision-making extends to implementing innovations that boost productivity and resilience. The third theme, “External Resource and Market Access”, brings together accessing information, accessing technology, accessing markets, and accessing finance, emphasizing women’s reliance on external support to fully participate in agricultural ventures. Lastly, the fourth theme, “Financial Management and Day-to-Day Operations”, includes the use of energy solutions and irrigation systems, coupled with managing income, managing expenditure, and accessing information, underscoring women’s active role in operational decisions as well as financial responsibilities. Overall, these themes highlight the breadth of women’s contributions, spanning planning, resource allocation, innovation adoption, financial management, and market engagement, while also underscoring the importance of broader systems of support to facilitate their decision-making capacity and success in agriculture.

Table 2.

An exploratory factor analysis a of the 17 variables related to decision-making as well as access and control of women in ECA in the Chitwan, Dhading, and Kavre districts in Bagmati Province, Nepal.

3.5. Relationships Between Socio-Demographic and Farm-Related Factors and ECA Continuation

The ordinal regression analysis revealed several significant factors influencing farmers’ willingness to learn Environmental Conservation Agriculture (ECA) in Chitwan, Dhading, and Kavre, Nepal (Table 3). Among the perceived effects of climate change, farmers who recognized the rise in sea temperature and extreme heat as threats were 20% more likely to be willing to learn ECA, highlighting how worsening climatic conditions drive the need for sustainable agricultural practices. Additionally, farmers who experienced crop losses due to climate change were 64% more likely to seek knowledge on ECA, emphasizing that direct economic losses serve as a strong motivator for adopting conservation-oriented farming.

Table 3.

Relationship of socio-demographic and farm-related factors with farmers’ willingness to learn ECA in Chitwan, Dhading, and Kavre districts at Bagmati Province, Nepal.

Regarding adaptation strategies, farmers already engaged in improved pest and disease management were more than twice as likely to be willing to learn ECA, suggesting that those familiar with proactive farming techniques see value in expanding their knowledge. Similarly, those planting high-yielding crops were 74% more likely to learn ECA, likely because they associate ECA with further productivity gains. However, farmers who had already adopted heat- and drought-tolerant crop varieties were 69% less likely to be willing to learn ECA, indicating that they may feel their current strategies sufficiently address climate challenges. A similar pattern emerged with the use of ICT tools and social media for farming, where farmers relying on these technologies were 67% less likely to seek additional knowledge, implying that they may perceive digital tools as adequate sources of information.

Market dynamics also played a role in farmers’ willingness to learn ECA. Those who sold their products through middlemen and traders were 70% more likely to be interested in learning, suggesting that these intermediaries may encourage sustainable farming practices or provide incentives for farmers who adopt them. Likewise, those selling in local open-air markets, known as hat bazars, were 59% more likely to learn, possibly because consumers in these markets demand eco-friendly and high-quality agricultural products. In contrast, farmers who sold their produce to large-scale processors or millers were 83% less likely to be willing to learn ECA, likely because these markets prioritize volume and standardization over conservation practices. Interestingly, farmers who primarily consumed their own produce were more than twice as likely to seek knowledge about ECA, suggesting that those prioritizing food security recognize the value of sustainable and chemical-free farming.

Personal motivations also significantly influenced the willingness to learn ECA. Farmers who cited personal health benefits as a reason for practicing ECA were 35% more likely to be willing to learn, underscoring the perception that sustainable farming leads to healthier food production. Similarly, those who believed that ECA enhances product quality were 43% more likely to seek further knowledge, reinforcing the idea that high-quality crops drive interest in conservation agriculture. Economic incentives also played a key role, with farmers who expected higher prices for ECA products being 27% more likely to learn, highlighting the importance of profitability in shaping willingness to adopt sustainable practices.

Gender dynamics were also significant, as women’s participation in early-stage planning and resource mobilization increased the likelihood of farmers being willing to learn ECA by 19%. This finding suggests that involving women in the decision-making process from the outset encourages greater engagement with ECA.

These findings are further supported by the Spearman correlation analysis, which highlights additional factors influencing farmers’ willingness to learn ECA (Table 4). Farmers who perceived their farming methods as climate-resilient or climate-smart exhibited a positive correlation with willingness to learn ECA, suggesting that those already engaged in sustainable farming practices are more inclined to continue expanding their knowledge. Likewise, farmers who expressed a general interest in ECA (r = 0.198, p < 0.01) were more likely to seek further education on the topic.

Table 4.

Spearman correlation of farmers’ willingness to learn ECA with ECA-related variables.

Institutional support also played a crucial role, as farmers aware of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) promoting ECA showed a significant positive correlation with willingness to learn. Similarly, those who received subsidies for ECA-related activities were more motivated to pursue additional knowledge, emphasizing the importance of financial support in driving adoption.

Perceptions regarding the broader benefits of ECA also influenced learning motivation. Farmers who believed that ECA could achieve sustainable income and productivity, improve adaptive capacity and resilience, and reduce greenhouse gases showed a significant positive correlation. Furthermore, those who perceived ECA as a tool for women’s empowerment were more inclined to learn, reinforcing the role of gender inclusivity in sustainable agriculture.

Interestingly, satisfaction with ECA product prices exhibited a negative correlation with willingness to learn. This suggests that farmers who are content with current price structures may see less need for additional knowledge or improvements in their practices.

Overall, these findings highlight that farmers’ willingness to learn ECA is driven by a mix of climate change experiences, economic opportunities, personal health concerns, and market dynamics. Institutional and financial support, along with perceived environmental and social benefits, further influence this willingness. While those already implementing certain adaptation strategies may feel less need for further learning, farmers experiencing climate-related crop losses, seeking higher-quality produce, and targeting consumer-driven markets show a strong inclination toward acquiring more knowledge about ECA. Additionally, the role of women in early planning stages underscores the importance of inclusive decision-making in fostering greater interest in sustainable agricultural practices. Moving forward, efforts to promote ECA should emphasize its economic and health benefits, align with market demands, and engage women in early planning to maximize adoption.

4. Discussion

This study provides critical insights into the socio-demographic, economic, and environmental factors influencing farmers’ willingness to learn about Environmental Conservation Agriculture (ECA) in Nepal, particularly in the context of gender dynamics and women’s empowerment in sustainable agriculture. Grounded in Social Learning Theory [30] and Empowerment Theory [31], the findings highlight the interplay between knowledge acquisition, social influences, and structural empowerment in promoting ECA adoption. These results have far-reaching implications for the future of Nepal’s agriculture, particularly in fostering climate resilience, improving livelihoods, and advancing gender equity. These also contribute to agrarian science by offering empirical evidence that connects social learning mechanisms and empowerment processes to sustainable agricultural practices in a developing-country context.

The findings reveal that 72.6% of farmers express a willingness to learn about ECA, reflecting a growing awareness of its benefits. However, willingness alone does not necessarily translate into actual adoption, as several external factors influence decision-making. Social Learning Theory suggests that individuals learn and adopt new behaviors by observing their environment, engaging with peers, and recognizing tangible benefits. In this study, farmers who have experienced climate-related crop losses (64%) are more inclined to learn about ECA, indicating that environmental stressors serve as catalysts for adaptation. This aligns with global research showing that climate vulnerability is a significant driver of conservation-oriented agricultural decisions (Meijer et al., 2015) [23]. Similarly, farmers engaged in consumer-driven markets (59%) demonstrate higher willingness to learn, likely due to the market incentives that favor eco-friendly practices. This is consistent with studies indicating that market access, consumer demand, and certification programs play a crucial role in driving sustainable agricultural transitions [24,37].

Spearman correlation analysis further strengthens these findings by identifying key ECA-related factors that significantly influence farmers’ willingness to learn. The study finds a positive correlation between farmers’ perception of ECA as a climate-resilient or climate-smart farming method and their willingness to engage with ECA. This aligns with the literature highlighting ECA’s role in enhancing soil carbon sequestration and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, demonstrating its tangible climate benefits [8,9,10]. Such evidence supports the importance of demonstration plots and peer interactions, which align with the Social Learning Theory, in clearly communicating ECA’s benefits. Additionally, interest in ECA and recognition of FAO’s promotion of ECA are significantly associated with willingness to learn, emphasizing the role of international organizations in shaping local farming practices. Farmers who perceive ECA as a means to achieve sustainable income, improved adaptive capacity, and reduced greenhouse gases are also more likely to engage in learning activities, highlighting the importance of economic and environmental messaging in ECA promotion [5,10].

Market dynamics also play a crucial role, as the correlation analysis reveals that price satisfaction for ECA products is negatively associated with willingness to learn. This suggests that dissatisfaction with current market prices for ECA products may serve as a barrier to engagement, reinforcing the need for improved market incentives, certification schemes, and cooperative-led pricing mechanisms to enhance profitability for ECA farmers. Conversely, farmers who receive ECA subsidies are more likely to be willing to learn, indicating that financial support mechanisms can significantly impact the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices.

A key contribution of this study is its exploration of the relationship between women’s empowerment and ECA adoption. In alignment with Empowerment Theory, the results indicate that households where women actively participate in early-stage agricultural decision-making are 19% more likely to express willingness to learn about ECA. This aligns with Empowerment Theory, which suggests that when individuals—particularly marginalized groups—gain access to decision-making processes and resources, they become more capable of driving meaningful change. Gender-inclusive agricultural policies, therefore, have the potential to not only enhance women’s roles in farming but also accelerate the adoption of sustainable practices. Further supporting this, the correlation analysis finds that perceptions of ECA as a tool for women’s empowerment are significantly associated with willingness to learn. This suggests that increasing recognition of the role of ECA in gender equity can further drive interest and participation in ECA [38,39].

This study’s identification of key barriers faced by women, such as socio-cultural constraints, resource and knowledge deficits, and institutional challenges, highlights critical areas for targeted interventions. For instance, addressing socio-cultural barriers by reducing women’s household workload and challenging gender norms can significantly enhance women’s active participation. Similarly, overcoming resource and knowledge deficits through educational programs, accessible financial support, and improved infrastructure aligns directly with the motivations identified in this research. These findings emphasize that tailored capacity-building initiatives, financial incentives, and supportive institutional structures are essential to overcoming barriers and leveraging motivators for increased ECA adoption among women.

Despite these promising trends, several barriers continue to hinder farmers’ ability to engage with ECA. The most significant constraints include financial limitations, restricted market access, and perceived risks associated with transitioning to ECA-based farming methods. The study also highlights that farmers who have already adopted other adaptation strategies, such as drought-resistant crops or ICT-based farming solutions, exhibit lower willingness to learn ECA. This suggests a substitution effect, wherein farmers who perceive their current strategies as sufficient may be reluctant to invest additional time and resources into learning new practices. Similar findings have been documented in previous research, where the perceived effectiveness of existing solutions reduced engagement with conservation agriculture [26]. These findings emphasize the need for tailored extension services that not only introduce ECA as a sustainable alternative but also integrate it with existing climate adaptation strategies to encourage broader adoption.

The findings of this study have several important policy and practical implications for Nepal’s agricultural sector. The practical policy implications derived from this study also link identified barriers to actionable solutions. Given that exposure to climate impacts and market incentives increases willingness to learn ECA, expanding peer-learning networks, farmer field schools, and participatory training programs could further accelerate adoption. Policies should encourage demonstration plots and model farms to showcase successful ECA practices, community-based knowledge-sharing initiatives where experienced farmers mentor others, and the incorporation of ICT-based agricultural extension services using mobile applications and radio programs to disseminate ECA knowledge more effectively. Since households where women are involved in decision-making are more likely to adopt ECA, policies should aim to increase women’s participation in agricultural leadership, which aligns with the Empowerment Theory. This can be achieved through targeted agricultural training programs for women, ensuring they gain technical knowledge and decision-making skills, microfinance and credit schemes tailored for women farmers, helping them access capital to implement ECA practices, and encouraging women’s representation in farmer cooperatives and community agricultural boards, ensuring they have a voice in shaping local agricultural policies.

Given women’s disproportionate agricultural constraints, interventions should aim to reduce their labor burdens associated with ECA through labor-saving technologies, childcare support, and policy incentives recognizing women’s agricultural contributions. Such initiatives are crucial given the increased labor demands on women farmers associated with practices like intercropping and reduced tillage, as documented by Halbrendt et al. (2014) [19].

Since market-driven farmers are more likely to engage with ECA, integrating sustainable farming into high-value markets could further incentivize adoption. Key strategies include providing premium prices for ECA-certified products through organic certification schemes, developing cooperative-led marketing strategies allowing small-scale farmers to collectively negotiate better prices, and investing in climate-resilient supply chains, ensuring farmers can transition to sustainable practices without financial risk. Since women face disproportionate constraints in agriculture, targeted interventions should aim to reduce the time and labor burden associated with ECA. This includes promoting labor-saving technologies, such as mechanized planting and irrigation systems, providing child-care support and social infrastructure allowing women to participate in training programs, and ensuring institutional recognition of women’s agricultural contributions through land tenure reforms and policy incentives.

Studying farmers’ willingness to learn ECA and its connection to women’s empowerment is crucial for Nepal’s agricultural development. With the country’s growing vulnerability to climate change, the transition to sustainable, conservation-based farming is not just an economic necessity but a strategic imperative for food security and rural livelihoods. By enhancing farmers’ access to knowledge, integrating gender-responsive policies, and providing market-based incentives, Nepal can improve climate resilience by reducing dependence on chemical-intensive agriculture, enhance economic opportunities for smallholder farmers, particularly women, and foster inclusive agricultural development, ensuring that marginalized groups—especially women—can actively participate in shaping Nepal’s agricultural future [40,41].

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the critical role of social learning, economic incentives, and gender empowerment in shaping ECA adoption in Nepal. Farmers’ willingness to learn ECA is strongly influenced by climate-related experiences, market access, and women’s involvement in decision-making. The findings reinforce the idea that gender-inclusive agricultural policies are not only necessary for women’s empowerment but are also instrumental in fostering climate-resilient farming communities. Women’s participation in early agricultural planning and decision-making creates more openness to innovation, reinforcing the need for institutional support that strengthens their leadership in agriculture.

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design captures farmers’ willingness to learn at a single point in time, limiting our ability to assess long-term behavioral shifts. Future research should employ longitudinal studies to track ECA adoption patterns over time and measure whether willingness translates into sustained implementation. Second, while the study focuses on three districts (Kavre, Dhading, and Chitwan), expanding research to other agro-ecological zones in Nepal would enhance the generalizability of findings. Additionally, qualitative research exploring women’s lived experiences in ECA adoption would provide deeper insights into the socio-cultural barriers influencing gender roles in sustainable agriculture.

The study’s findings underscore the need for targeted policy interventions and practical measures to enhance ECA adoption while promoting gender-inclusive agricultural development [36]. Given that exposure to climate stressors and market incentives increases willingness to learn ECA, expanding farmer-to-farmer knowledge-sharing platforms, demonstration plots, and participatory training programs can accelerate the dissemination of sustainable agricultural practices. Market-driven incentives, such as certification programs and premium pricing for ECA products, should be promoted to encourage greater participation among farmers. For instance, establishing certification standards through collaboration with local and international certification bodies can create tangible market opportunities. Furthermore, setting up district-level demonstration plots managed by successful adopters can provide real-world examples that clearly illustrate economic benefits, reducing farmers’ uncertainty about transitioning to ECA.

In Nepal, each municipality and rural municipality has an agriculture and agriculture extension section which disseminates agricultural technology, good practices in the locality, and distributes better seeds to the farmers from the central departments. For the specific real-world example in this study area, ECA products can be sold to the bulk buyers, such as resort hotels in Dhulikhel in Kavre, national park resorts in Chitwan, and Kurintar resorts adjacent to Dhading. Such resorts and hotels serving international and domestic tourists purchase quality ECA products at relatively high prices from the local farmers on trust-based transactions. Local ECA farmers can benefit from such buyers, and each municipality and rural municipality can be the linchpin. Thus, this can be applicable to any such region elsewhere.

Another significant implication of this study is the necessity for gender-inclusive policies in agriculture. Given that households where women participate in decision-making are more likely to adopt ECA, policymakers should focus on increasing women’s leadership roles in farming cooperatives, agricultural committees, and community resource management initiatives. Providing targeted training programs for women farmers, ensuring access to credit, and implementing land tenure reforms are crucial steps toward achieving this goal. Furthermore, recognizing and reducing the unpaid labor burden on women through labor-saving technologies, childcare support, and community-based agricultural assistance programs can further enhance their engagement in sustainable agriculture. For example, the government could implement targeted micro-financing programs specifically aimed at women farmers, accompanied by capacity-building workshops on financial management and agricultural best practices. Additionally, introducing simple, cost-effective labor-saving tools and machinery, such as hand-operated seed planters or affordable drip irrigation systems, could significantly alleviate women’s workload.

The practical contributions of these findings to sustainable agricultural development are substantial. By clearly identifying and addressing the barriers to ECA adoption—such as limited market access, insufficient financial incentives, and gender disparities in resource access—this research provides concrete pathways for achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly those related to gender equality (SDG 5), climate action (SDG 13), and sustainable agriculture (SDG 2). Enhanced ECA adoption can lead to improved soil health, reduced environmental degradation, and increased agricultural productivity, directly benefiting food security and rural livelihoods in the region. Furthermore, empowering women through targeted interventions aligns with broader national development priorities, creating inclusive growth opportunities and strengthening community resilience against climate impacts.

To accelerate ECA adoption and support Nepal’s climate resilience goals, policymakers, development organizations, and agricultural stakeholders must implement knowledge-sharing initiatives, financial incentives, and institutional reforms that prioritize gender equity. Expanding farmer education programs, improving access to markets, and integrating ECA into national agricultural strategies will be crucial in achieving sustainable food production and climate resilience. Moreover, addressing gender disparities in land ownership, financial resources, and agricultural training will further empower women, ensuring they play a central role in Nepal’s agricultural transformation.

Nepal stands at a pivotal moment in its agricultural development. By addressing key barriers and leveraging economic motivators, the country can foster a more inclusive, sustainable, and climate-resilient agricultural sector. Moving forward, an integrated approach that combines economic, environmental, and social strategies will be essential in ensuring that ECA adoption not only improves productivity but also strengthens rural livelihoods and gender equity. Only through such comprehensive efforts can Nepal achieve long-term food security, economic stability, and environmental sustainability in its agricultural sector.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15070726/s1, Table S1. Socio-demographic and ECA-related characteristics of the sampled ECA farmers in Chitwan, Dhading, and Kavre, Nepal. Table S2. Women involvement, decision-making, access, and control in ECA in Chitwan, Dhading, and Kavre, Nepal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.M. and C.M.G., methodology, K.L.M.; software, K.L.M. and C.M.G.; validation, K.L.M. and C.M.G.; formal analysis, K.L.M. and C.M.G.; investigation, K.L.M.; resources, K.L.M.; data curation, K.L.M. and C.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L.M. and C.M.G.; writing—review and editing, K.L.M. and C.M.G.; visualization, K.L.M. and C.M.G.; supervision, K.L.M.; project administration, K.L.M.; funding acquisition, K.L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University (Approval code: HUIDEC-2022-0090).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all the farmers who participated in this study for their valuable time and insights. The authors would also like to thank Manjeshwori Singh and Shree Kumar Maharjan for their contributions in managing the surveys to collect the data. Authors also extend their gratitude to Ruth Joy Sta. Maria for her expertise in creating the map featured in this paper and to Zoe Kahlille L. Tagubar for her contributions in designing the graphs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- MOF. Economic Survey 2023/24; MOF: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Krupnik, T.; Timsina, J.; Devkota, K.; Tripathi, B.; Karki, T.; Urfels, A.; Gaihre, Y.; Choudhary, D.; Beshir, A.; Pandey, V.; et al. Agronomic, socio-economic, and environmental challenges and opportunities in Nepal’s cereal-based farming systems. Adv. Agron. 2021, 170, 155–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, B.; Thapa, R.; Dhakal, S.C.; Devkota, D.; Kattel, R.R. Feminization of Agriculture in Nepal and its implications: Addressing Gender in Workload and Decision Making. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 10, 2484–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Nepal. Nepal’s Long-Term Strategy for Net-Zero Emissions; Government of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2021.

- Maharjan, K.L.; Gonzalvo, C.; Aala, W. Dynamics of Environmental Conservation Agriculture (ECA) Utilization among Fujioka Farmers in Japan with High Biodiversity Conservation Awareness but Low ECA Interest. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, K.; Gonzalvo, C.; Singh, M. Farmer Perspectives on the Economic, Environmental, and Social Sustainability of Environmental Conservation Agriculture (ECA) in Namobuddha Municipality, Kavre, Nepal. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R. Farmers’ perception on agro-ecological implications of climate change in the Middle-Mountains of Nepal: A case of Lumle Village, Kaski. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkama, E.; Kunypiyaeva, G.; Zhapayev, R.; Karabayev, M.; Zhusupbekov, E.; Perego, A.; Schillaci, C.; Sacco, D.; Moretti, B.; Grignani, C.; et al. Can conservation agriculture increase soil carbon sequestration? A modelling approach. Geoderma 2020, 369, 114298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Hobbie, E.A.; Feng, P.Y.; Niu, L.A.; Hu, K.L. Can conservation agriculture mitigate climate change and reduce environmental impacts for intensive cropping systems in North China Plain? Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharjan, K.L.; Gonzalvo, C.M.; Aala, W.F. Drivers of Environmental Conservation Agriculture in Sado Island, Niigata Prefecture, Japan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, K.L.; Gonzalvo, C.M.; Baggo, J.C. Balancing Tradition and Innovation: The Role of Environmental Conservation Agriculture in the Sustainability of the Ifugao Rice Terraces. Agriculture 2025, 15, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, J.; Regmi, R.; Ghimire, R.; Puri, K.; Gyawaly, S.; Poudel, S. Farmers’ Knowledge on Pesticide Safety and Pest Management Practices: A Case Study of Vegetable Growers in Chitwan, Nepal. Agriculture 2018, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, K.; Udas, E.; Bhatta, L. Ecosystem-based adaptation for increased agricultural productivity by smallholder farmers in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, N.; Sitaula, B.K.; Bajracharya, R.M. Agricultural Intensification: Linking with Livelihood Improvement and Environmental Degradation in Mid-hills of Nepal. J. Agric. Environ. 2010, 11, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.; Ghimire, R.; Kharel, T.; Mishra, U.; Clay, S. Conservation agriculture for food security and climate resilience in Nepal. Agron. J. 2021, 113, 4484–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Gender and Access to Land; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2002.

- Balayar, R.; Mazur, R. Women’s decision-making roles in vegetable production, marketing and income utilization in Nepal’s hills communities. World Dev. Perspect. 2021, 21, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, N.; Raya, B.; Sitaula, B.; Bajracharya, R.; Kristjanson, P. Gender roles and greenhouse gas emissions in intensified agricultural systems in the mid-hills of Nepal. In CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security; CGIAR: Montpellier, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halbrendt, J.; Kimura, A.H.; Gray, S.A.; Radovich, T.; Reed, B.; Tamang, B.B. Implications of Conservation Agriculture for Men’s and Women’s Workloads Among Marginalized Farmers in the Central Middle Hills of Nepal. Mt. Res. Dev. 2014, 34, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008.

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Pillarisetti, J.R.; McGillivray, M. Human Development and Gender Empowerment: Methodological and Measurement Issues. Dev. Policy Rev. 1998, 16, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, S.; Catacutan, D.; Ajayi, O.; Sileshi, G.; Nieuwenhuis, M. The role of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions in the uptake of agricultural and agroforestry innovations among smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2015, 13, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Läpple, D.; Van Rensburg, T. Adoption of organic farming: Are there differences between early and late adoption? Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczyk, J. The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy and Food Security. In Proceedings of the 10th International Scientific Conference: Economic Policy in the European Union Member Countries, Karvina, Czech Republic, 1 January 2013; pp. 228–238. [Google Scholar]

- Knowler, D.; Bradshaw, B. Farmers’ adoption of conservation agriculture: A review and synthesis of recent research. Food Policy 2007, 32, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart-Getz, A.; Prokopy, L.; Floress, K. Why farmers adopt best management practice in the United States: A meta-analysis of the adoption literature. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 96, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenmann, G.; Schaer, M. Social Learning Theories. Sprache-Stimme-Gehor 2006, 30, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRUSEC, J. Social-Learning Theory and Developmental-Psychology-The Legacies of Sears, Robert and Bandura, Albert. Dev. Psychol. 1992, 28, 776–786. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, D.; Zimmerman, M. Empowerment theory, research, and application. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 569–579. [Google Scholar]

- Spangler, K.; Christie, M. Renegotiating gender roles and cultivation practices in the Nepali mid-hills: Unpacking the feminization of agriculture. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upreti, B.; Ghale, Y.; Shivakoti, S.; Acharya, S. Feminization of Agriculture in the Eastern Hills of Nepal: A study of Women in Cardamom and Ginger Farming. Sage Open 2018, 8, 2158244018817124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balayar, R.; Mazur, R. Beyond household income: The role of commercial vegetable farming in moderating socio-cultural barriers for women in rural Nepal. Agric. Food Secur. 2022, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, P.; Devkota, N.; Maraseni, T.; Khanal, G.; Deuja, J.; Khadka, U. Does joint land ownership empower rural women socio-economically? Evidence from Eastern Nepal. Land Use Policy 2024, 138, 107052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, K.L.; Singh, M.; Gonzalvo, C.M. Drivers of environmental conservation agriculture and women farmer empowerment in Namobuddha municipality, Nepal. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 13, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastase, P.; Toader, M. Study Regarding Organic Agriculture and Certification of Products. Sci. Pap. Ser. A-Agron. 2016, 59, 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Ondiba, H.; Matsui, K. Drivers of environmental conservation activities among rural women around the Kakamega forest, Kenya. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 10666–10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, T.; Athinuwat, D. Key factors of women empowerment in organic farming. Geojournal 2021, 86, 2501–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, M.; Clement, F.; Leder, S. Women?s empowerment and the will to change: Evidence from Nepal. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 94, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Pingali, P.; Pinstrup-Andersen, P. Women’s empowerment in Indian agriculture: Does market orientation of farming systems matter? Food Secur. 2017, 9, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).