1. Introduction

The competitive nature of European agriculture is shaped by a multitude of determinants, encompassing political, production-related, environmental, and sustainability dimensions. Agriculture has historically constituted, and persists in being, a pivotal sector within the European economy, especially amidst the contemporary economic, social, climatic, and geopolitical challenges engendered by the global crisis and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine [

1].

The European Union endeavors to bolster its member states through a comprehensive agricultural policy that promotes investments in agricultural output, the endorsement of premium agricultural products, environmental sustainability, rural advancement, enhanced market transparency, and the facilitation of innovation within the agricultural sector. The predominant challenges confronting agricultural production within the European Union encompass competition in the global marketplace, economic and political upheavals, climate change, and escalating production expenses. The European Union aspires to furnish support for sustainable agricultural incomes and the overall stability of the agricultural sector while making significant contributions to the financing of agriculture in its member states. In this regard, it ambitiously seeks to guarantee long-term food security and agricultural diversity across its member states [

2].

Cheba and Szopik-Depczyńska [

3] ask whether it is possible to speak of equality in the competitiveness of economies in today’s globalized world. This issue is especially significant for political and economic entities such as the European Union. Economic competitiveness is among the most widely debated topics today. Beyond the challenges of defining the concept, there are also critical questions concerning how to measure competitiveness.

According to Nowak and Zakrzewska [

4], the assessment of variations in agricultural competitiveness among EU member states necessitates the formulation of a suitable array of indicators to ascertain whether a nation is enhancing its competitive stature. Their investigation reveals that disparities exist in agricultural competitiveness across member states. Between the years 2012 and 2021, Denmark, The Netherlands, and Belgium emerged as the most competitive nations. Throughout this decade-long interval, the hierarchy of agricultural competitiveness underwent alterations, with Finland, Slovakia, and Ireland exhibiting the most substantial advancements. Nevertheless, considerable disparities persist between the older and newer member states. None of the newer member states managed to secure a position within the top ten in terms of agricultural competitiveness. The authors deduced that the proportion of EU agricultural production within the EU’s agricultural product exports elucidates the variances in agricultural competitiveness among member states. The expansion of the European Union in the years 2004, 2007, and 2013 facilitated the emergence of opportunities for unimpeded trade, culminating in augmented trade flows and an escalated demand for agricultural products. While the processes of integration have amplified competition among member states, they concurrently have engendered novel prospects. Empirical studies indicate that notwithstanding the enhancement in labor productivity within the new member states relative to the original EU member states (designated as the EU-15), a disparity persists in the effective utilization of production factors. The comprehensive competitiveness of the EU-13 nations within the agricultural trade sector in the common market has seen an improvement; however, a more granular examination uncovers disparities among the individual states. In the year 2020, the principal exporters exhibiting a comparative advantage included Hungary, Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Croatia, whereas Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Estonia experienced a comparative disadvantage and were categorized as net importers [

5].

According to Mastylo [

6], farms represent a unique category of agricultural enterprises, serving as the organizational and economic foundation for rural development. Their role in enhancing the competitiveness of the domestic agricultural sector continues to grow. Farm competitiveness is shaped by both external and internal factors, which are evaluated in the context of regional development trends. The institutional environment plays a crucial role in regulating these factors by addressing the knowledge gaps among farmers and reducing transactional costs through the development of tailored business plans and behavioral models. Given the specific characteristics of agricultural sector development and the effort to strengthen the competitiveness of agro-holdings, numerous challenges hinder farm development. These include inadequate technical and technological support, selling products below cost, marketing and sales difficulties, seasonal inflationary trends, limited access to credit resources, and insufficient state subsidies. Addressing these challenges requires a strategic approach to managing farm competitiveness. A strategic analysis that takes a systematic approach to studying the relationships between quantitative and qualitative aspects of farm development—while also considering restrictive factors such as low demand for products, unfavorable weather conditions, labor shortages, limited access to materials and equipment, financial constraints, and insufficient managerial skills—enables the identification of key objectives. These objectives aim to resolve critical issues and uncover opportunities for improving farm efficiency by analyzing the internal and external environment.

The recent legislative initiatives pertaining to the reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for the period of 2021–2027 are designed to bolster a sustainable and competitive agricultural sector. The revised CAP actively promotes the role of agriculture in advancing climate protection, enhancing biodiversity, conserving the environment, and augmenting the competitive position of farms within the agri-food sector in the European framework. The focus on robust outcomes and performance within the CAP legislation necessitates ongoing evaluation and monitoring of the efficacy of the measures implemented [

7].

Agricultural subsidies are a controversial topic in the global debate on the profitability, competitiveness, and sustainability of farms. The impact of agricultural subsidies on the profitability and sustainability of farms worldwide has also been the focus of the latest studies, such as Mamun [

8]; Georgieva [

9]; Abad-Segura et al. [

10]; Sopian et al. [

11]; Sha et al. [

12]; Kargi and Bachev [

13]; Kravčáková Vozárová and Kotulič [

14]; Kravčáková Vozárová et al. [

15]; Jablowski [

16]; Volyk et al. [

17]; Svobodova et al. [

18]; Arisoy [

19]; and Valach [

20].

The study by Mishra et al. [

21] combines an extensive review of the existing literature, with data analysis to assess the effectiveness of various subsidy programs in boosting agricultural production and stabilizing incomes. The results indicate that although subsidies have facilitated short-term increases in agricultural production and farmer income, their long-term implications for profitability and sustainability remain ambiguous. In many cases, subsidies have led to overproduction, market imbalances, and environmental damage, ultimately undermining the long-term sustainability of agricultural systems. The research underscores the necessity for a more focused and efficient strategy for agricultural support that prioritizes the conservation of resources, resilience to climate change, and rural development. It also highlights the significance of allocating resources towards research, development, infrastructure, and advisory services to bolster the competitiveness and sustainability of the agricultural sector. The study concludes by advocating for a gradual transition from input-based subsidies to more decoupled forms of assistance, to more effectively align agricultural policies with the objectives of profitability and sustainability.

Agricultural subsidies are prevalent in nearly all nations across the globe. The primary objective of these subsidies is to ensure adequate food production while securing a fundamental income for agricultural producers. In most nations, this is accomplished by elevating long-term price levels above those determined by free market dynamics and/or by delivering direct financial transfers to farmers. Nevertheless, subsidies have faced scrutiny due to their potential detrimental impacts on economic welfare, environmental integrity, and public health. [

22].

According to Rovný [

23], given the structure of farms in Slovakia, the greatest influencer of agriculture is the subsidy policy. Just like any other country, Slovakia has its own specific conditions that affect agricultural production, and changes in subsidy policies have caused problems for many enterprises operating according to the conditions of their respective regions. Lower subsidies for agro-commodities, previously supported due to higher costs (e.g., potatoes in mountainous areas, vegetable production in the southern regions of Slovakia, livestock farming, and sheep breeding), have resulted in reduced yields and, consequently, liquidation. The area-based payment system completely changed the situation in Slovak agriculture. The result of this subsidy policy has been a shift from traditional and cost-intensive crops to the cultivation of monoculture cereals and oilseeds, which have much lower production costs. This, combined with support per hectare of cultivated land, significantly affects the profitability of production. Since a large percentage of agricultural land in Slovakia is managed by a small number of agricultural enterprises, about a fifth of the beneficiaries receive approximately 94% of direct payments, which is the highest percentage among EU countries in terms of concentration of direct payments. This prioritization in production is a result of the interest in increasing the profitability of agricultural production. On the other hand, Svobodová et al. [

18] state that, when comparing with the Czech Republic, the assessment of the subsidy-to-agricultural-production ratio reveals that small farms received agricultural subsidies 2.3 times higher per unit of agricultural production than very large farms. However, the largest farms achieved the highest profitability ratios, followed by medium-sized farms, and then small farms. A comparable study was carried out in Poland by Staniszewski and Borychowski [

24], where the findings support the hypothesis that the effect of subsidies on efficiency is influenced by farm size. A statistically significant, positive impact of subsidies was observed only among the largest farms. The authors argue that these findings question the effectiveness of the CAP and suggest that, in its current form, the policy may disrupt market mechanisms and lead to the phenomenon of “rent-seeking”.

In the fiscal framework for the years 2021–2027, the European Commission has designated a sum of €365 billion for the sectors of agriculture and rural development under the auspices of the CAP, in contrast to the €416 billion allocated in the preceding fiscal framework. Of the earmarked resources for the present financial framework, €265.2 billion is specifically allocated for direct payments (previously €294.9 billion), while €78.8 billion has been reserved for rural development (previously €95.3 billion). Furthermore, an allocation of €20 billion has been established for market support and an additional €10 billion for the Horizon Europe research initiative. Collectively, the budgeted resources from the EU budget in the financial framework for 2021–2027 account for 88% of the allocations in the preceding framework pertaining to CAP measures. The newly instituted funding regulations denote an expanded range of authorities conferred by the European Commission to member states within the context of subsidiarity. Consequently, member states will be empowered to exercise their fiscal authorities to a greater degree, thereby accommodating local conditions and requirements in the strategic planning of agricultural and rural domains. The primary objective of the CAP, consistent with the previous framework, will be to implement measures that bolster sustainable agriculture and facilitate rural development within individual member states [

25].

The competitiveness of farms refers to a farm’s ability to produce goods efficiently and at a lower cost while maintaining quality, in comparison to other farms in the same market. Farms that are competitive can better adapt to market demands, technological advancements, and economic conditions. This ability enhances their market share and financial efficiency. Therefore, we examined the impact of subsidies, i.e., financial support, on the competitiveness of farms in Slovakia in a broader context. The aim was to determine how these subsidies influence cost-effectiveness, productivity, and the ability of farms to compete in the market, not only in the short term but also in the long term.

2. Materials and Methods

Financial assistance for agricultural businesses is a key priority of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), making the assessment of transfer efficiency a crucial aspect of policy evaluation. The analysis is based on data which were provided by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of the Slovak Republic (MPRV SR) in the form of anonymized data sheets. These sheets contained economic and financial data from entities managing 81.3% of the agricultural land in the country and served as the basis for analyzing annual trends in chosen economic and financial metrics. This material was a key source of information about the actual economic condition of farms, and therefore, it is important to emphasize that this database provides sufficiently extensive and relevant foundation for the foundational data. The sample consisted only of businesses with consistent financial records throughout the study period, ensuring data accuracy and balanced financial statement control (

Table 1). This study examines a group of farms within Slovakia’s agricultural sector over a 16-year span, from 2004 to 2019, incorporating the most recent available data. We are continuing our efforts to acquire more recent data, as the process is highly time intensive. Data from 2020 onwards were obtained from the MPRV SR; however, changes in the data collection methodology led to incompatibility with the database from the earlier period. This fact, however, does not exclude the possibility of conducting competitive analysis using the RCR index once the current data is obtained.

The methods used include an empirical analysis of the literature collected from both domestic and international scientific studies. To analyze competitiveness, we applied Porter’s generic strategy of cost minimization, also known as cost leadership, which emphasizes gaining a competitive edge through cost optimization. This approach was evaluated using the Relative Cost Ratio (RCR), which helps determine how efficiently farms manage their costs compared to competitors. The RCR index functions as a ratio-based measure, incorporating two key variables in its calculation [

26]:

where RCR

i is the RCR coefficient in year i, C

i denotes costs in year i, and R

i represents revenues in year i. Costs (C) include procurement costs + production consumption + personal expenses + depreciation + taxes and fees. Revenues (R) consist of sales revenues + production + subsidies. If the RCR falls between 0 and 1, it indicates a clear competitive advantage, as revenues surpass costs. Conversely, if the RCR exceeds 1, it signals a competitive disadvantage, as revenues are inadequate to cover the costs of non-tradable domestic inputs.

To achieve the main aim of this study, we sought answers to the following research hypotheses:

H1: We hypothesize that there is a statistically significant relationship between the competitiveness of Slovak farms and financial support through EU subsidies.

H2: We hypothesize that there are statistically significant differences in the competitiveness of Slovak farms between those that receive subsidies and those that do not.

3. Results

The Common Agricultural Policy represents a regulatory framework that is subject to continual amendments in response to evolving domestic conditions and dynamic global changes. One of its primary objectives has historically been and remains the enhancement of agricultural competitiveness. Presently, there exists a discernible further transition in European Union policy towards an augmented emphasis on environmental and climatic considerations. Consequently, a critical dimension must be considered to mitigate disparities in the developmental status and competitive position of agriculture across individual states of the EU, alongside the competitive international standing of EU agriculture. To bolster agricultural competitiveness, it is imperative to focus on harmonizing the instruments of structural policy with the specific requirements of the respective member states [

27].

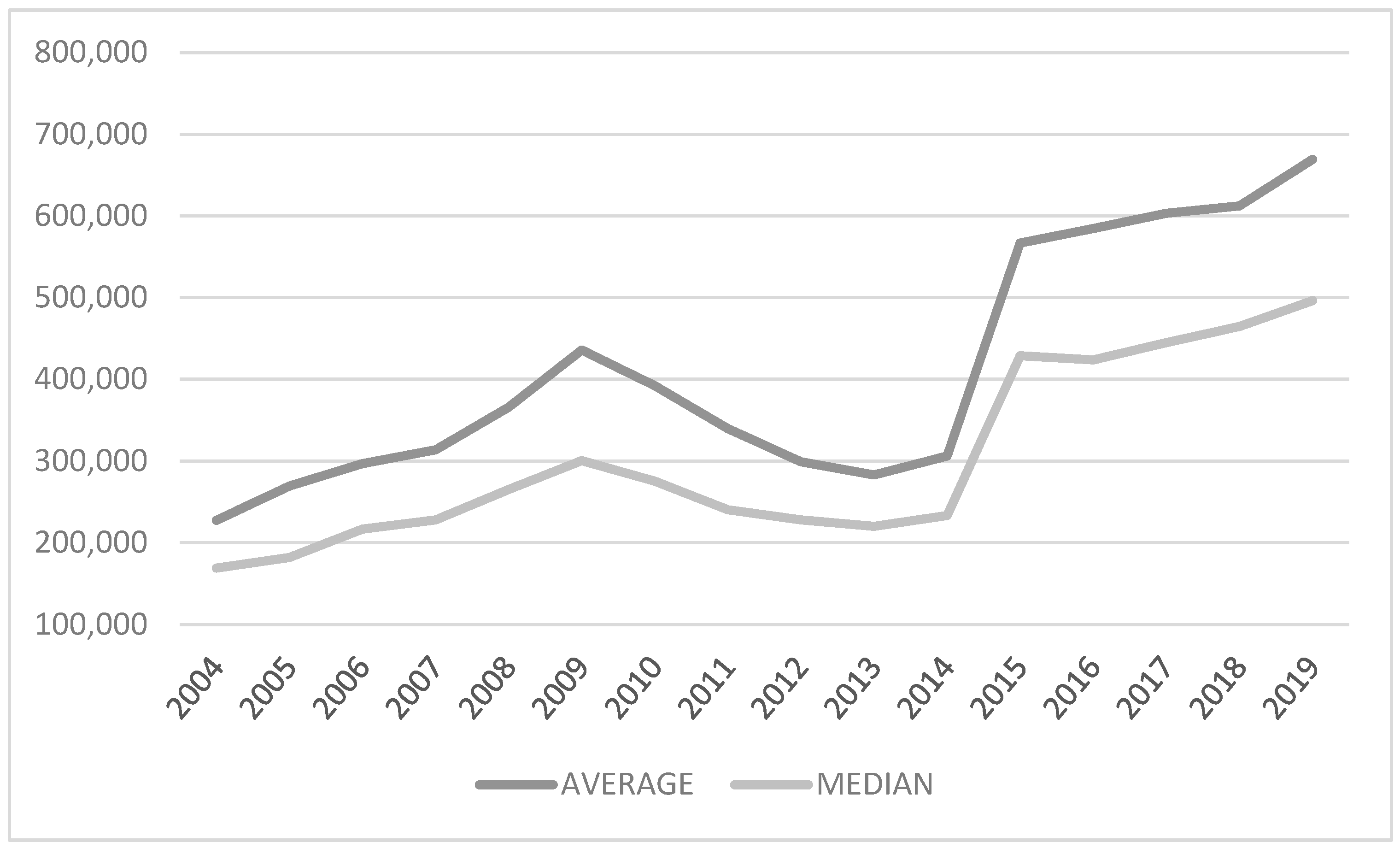

In the following section, we will address the relationship between the competitiveness of Slovak farms in the context of EU subsidies within the observed period. In 2009, the average annual support amount was €435,775, which represents an increase of 47.79% compared to 2004. After that year, the support amount decreased, reaching its lowest point in 2013. According to data from the MPRV SR [

28], agriculture recorded a negative pre-tax operating result for 2013, with a loss of €6.3 million. Year-on-year, the operating result decreased by €41.3 million, which led to a decline in the economic performance of agriculture. Compared to 2009, the average annual support per enterprise decreased by 35%. The operating result in 2013 was influenced by several factors, primarily the faster decline in revenues (20.3%) compared to costs (18.8%), a drop in the sales of own products (4.3%), a degressive price trend for commodities, and significant price disparities, which were reflected in widening price gaps, i.e., a reduction in agricultural product prices and a rise in input costs. In 2013, there was also a 6.0% decline in agricultural production, with a significant reduction in labor costs, which was more closely related to a decrease in the number of employees in the agricultural sector compared to the previous year, as well as the impact of climate change with fluctuating weather patterns throughout the year, causing local effects on agricultural production. An important factor was also the sale (hedging) of commodities through futures markets at pre-determined prices, which led to a greater import of finished food products and an increase in the export of primary agricultural raw materials. As a result, this led to a decrease in production, employment, and particularly a reduction in the share of domestic production in the Slovak market.

A subsequent increase occurred in 2015, when agriculture achieved a positive operating result, i.e., a profit of €30.5 million. The share of total subsidies in revenues reached 36.7%, and their volume increased by 23.6% year-on-year. This was due to the drawdown of financial resources from the Rural Development Program of the Slovak Republic 2007–2013 and the new Rural Development Program 2014–2020. This also demonstrated that subsidies improved the operating result, and without them, most farms would have been unprofitable [

29]. These results are confirmed by the median payment values (

Figure 1).

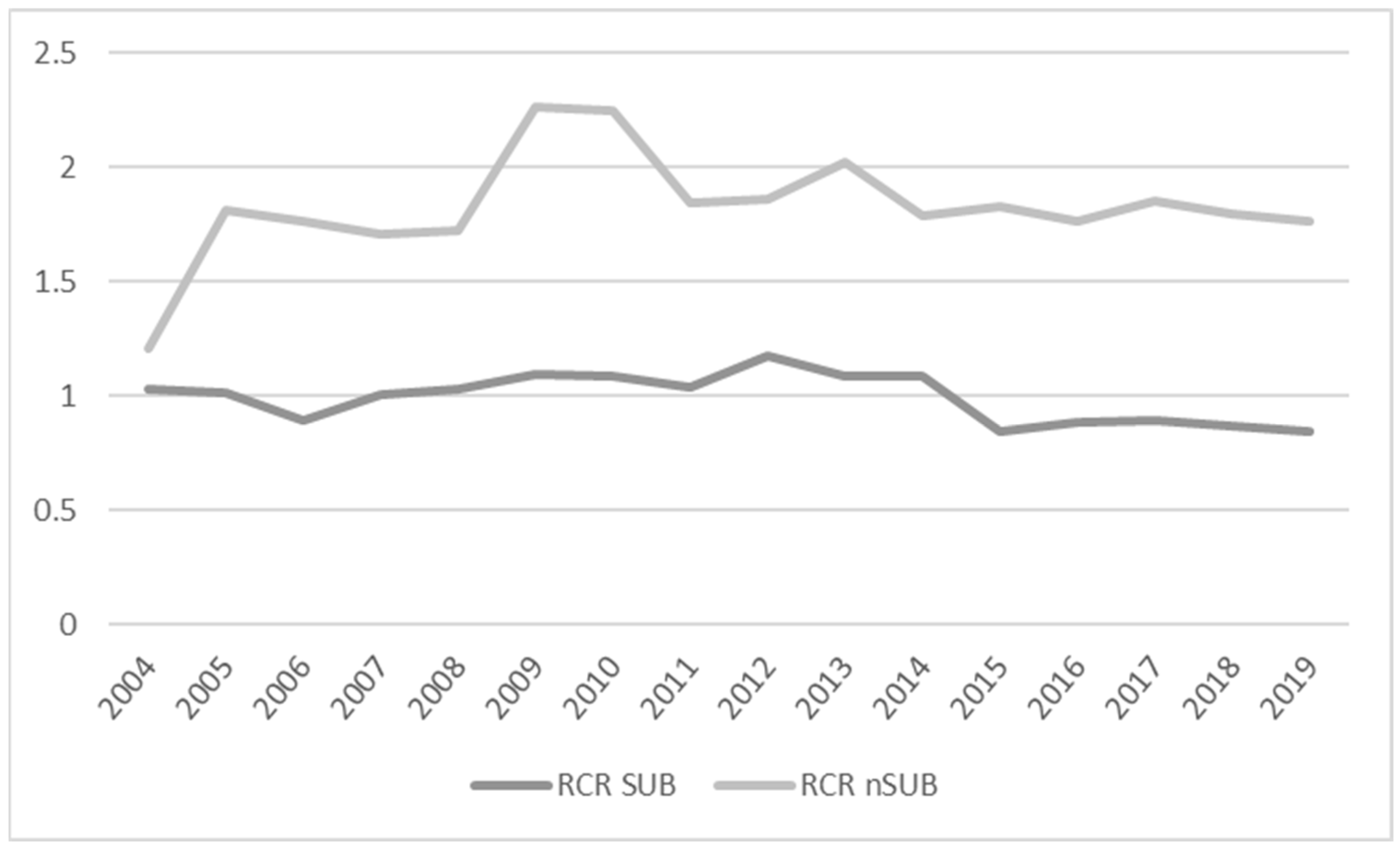

The following part aims to verify the existence of a relationship between the competitiveness of farms, expressed through the RCR coefficient, and financial support through subsidies. Since the RCR coefficient represents the ratio of costs and revenues, including subsidies, we expected to find a relationship. However, we were primarily interested in the strength of this relationship. To verify Hypothesis 1, we used Spearman’s correlation coefficient ρS, and the values are presented in

Table 2. The hypothesis was tested using comprehensive data for the entire observed period, i.e., from 2004 to 2019 (all years), as well as individually for the observed years.

Using Spearman’s correlation coefficient, a statistically significant negative correlation was confirmed between the competitiveness of agricultural enterprises and financial support through subsidies in all observed years and for the entire observed period, except for the year 2013. Although a relationship between the observed variables was confirmed, the correlation coefficients indicate that the strength of this relationship is weak.

This is also evident when testing the specific relationship between the mentioned variables for the entire observed period using linear regression (i.e., the least squares method), see

Table 3. Although the calculated coefficients for subsidies are statistically significant, the resulting model explains less than 1% of the variability in the RCR coefficient with subsidies. While we can say that there is some relationship between the variables, this relationship is unfortunately weak, and therefore, it is necessary to consider additional variables entering the model. These findings suggest the need to identify additional factors that could more effectively support the competitiveness of farms in Slovakia. From the viewpoint of Slovak farmers, their competitiveness is mainly affected by the import of food products that are heavily subsidized from abroad. As a result, establishing a fair subsidy system for all EU countries and eliminating discrimination against Eastern European nations is a crucial issue for them.

Figure 2 reveals a notable disparity in competitive levels between businesses that received EU subsidies and those that did not. The figure also clearly shows that subsidies significantly contribute to the revenue side of the RCR coefficient, pushing its value downward. Although in 2004, the competitiveness level had a positive result of 1.028, the RCR coefficient fell below 1 when revenues exceeded costs as early as 2006.

The agricultural sector achieved a positive pretax result in 2006 of 1.3 billion SKK (43.15 million EUR). This positive profitability development was due to a faster increase in revenues of 8.1%. Sales of own products increased by 1.4% year-on-year, but the decisive factor for the more competitive economic development of agricultural enterprises was the year-on-year growth in subsidies, particularly direct payments, which rose by 6.7%. A key factor affecting the financial performance of Slovak farms in 2006, apart from the increase in direct payments, was the shift away from inefficient production, the rise in input prices, the drop in agricultural product prices, and changes in internal organizational inventories [

30].

In 2012, businesses reached their lowest competitiveness level, which may have been caused by a decline in the economic performance of agriculture, evidenced by a significant year-on-year reduction in revenues (by as much as 23.8%). According to MPRV SR [

30], subsidies remained the primary financial source for the operation of businesses. EU resources set a limit for direct subsidies under SAPS at 90% of the EU-15 average. These funds could be increased from national sources through national compensatory payments up to 10%, i.e., to 100% of the EU-15 average. The modulation of direct payments also subsequently affected the amount of the national compensatory payment for 2012. The national budget approved 4.5% (18 million EUR) from the 10% limit for national compensatory payments, meaning that the total level of direct payments in Slovakia in 2012 remained below the average of the old EU member countries (EU-15), which impacted the competitiveness of Slovak farmers on the European market.

To verify Hypothesis 2, we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and the results are shown in

Table 4. The test confirmed the existence of statistically significant differences in the competitiveness of agricultural enterprises in the case of receiving/not receiving subsidies. These results, like those in the case of H1, suggest that subsidies have an impact on the competitiveness of agricultural enterprises in Slovakia.

4. Discussion

Slovak agriculture has a relatively smaller production share within the European Union, as Slovakia is a country with a smaller land area and thus a more limited share of agricultural land compared to larger member states such as Germany, France, or Poland.

Typical for the Slovak agricultural sector is the targeting of most payments as direct payments, with less investment in the structural development of agriculture. The adaptation of larger farms to this policy is natural, and the effort to achieve profitability is understandable. However, agriculture should not only be assessed from a business perspective, i.e., achieving profit, but also from the standpoint of its function in ensuring the food security of the population and its impact on the country and region. The cultivation of large areas with cereals and oilseeds creates the potential for the export of raw materials. This affects the structure of exports, where the primary production, which is mainly exported, is economically the least advantageous. As a result, there is an import of processed products. Often, this involves the initial export of raw materials, which, after processing, are imported back into the country of origin, of course, with added value. This represents a significant loss for the agro-industry, which naturally impacts Slovakia’s economic performance [

23].

According to Uhrinčaťová et al. [

31], the agricultural sector holds a specific position within the economic sectors of Slovakia, due to the functions it performs for society. It is not only about food production but also about shaping the state of the country, impacting the quality of the environment, playing an irreplaceable environmental role, and representing a way to increase the potential for developing supplementary activities, such as agri-business in tourism. Slovak agriculture is an integral part of the national economy, and recently, structural changes have been occurring that significantly influence Slovak agricultural production, food price development, and rural development. The Slovak Republic has implemented a new Strategic Plan for the Common Agricultural Policy for 2023–2027, which emphasizes sustainable agriculture, environmental protection, and adaptation to climate change. In this context, it can be stated that Slovak agriculture in 2023 has undergone a period of adaptation to new challenges and opportunities, focusing on increasing its competitiveness within the European Union.

Agricultural competitiveness represents a subject of longstanding discourse; however, it has recently re-emerged as a focal point for scholarly investigation due to various factors including climate change, food security, price volatility, and structural transformations. This resurgence of interest has resulted in a proliferation of scholarly articles addressing this theme, thereby shaping research trends and the organizational framework within this domain. In the prevailing context of globalization and transformation, food supply, food security, and agricultural advancement constitute pivotal elements of stability for each nation-state. The agricultural sector necessitates the enhancement of competitiveness alongside the cultivation of competitive advantages, given that agricultural production entails a high degree of business risk. Competitive advantages are a fundamental aspect of competitiveness; thus, the enhancement of the competitiveness of agricultural enterprises and the optimization of their operations amidst uncertain conditions are paramount objectives for the agricultural sector within every national economy [

17,

32].

Dombrovschii [

33] argues that the primary goal of agricultural enterprises is driven by the growing demands of the population and the processing industry for agricultural goods, along with the economic and financial outcomes. Achieving this goal depends on running a profitable business supported by a well-structured system of state assistance. This assistance is facilitated via fiscal allocations from the governmental budget aimed at stimulating investments within the agricultural domain. Subsidies function as a mechanism of governmental support for agrarian enterprises and households, contributing to the enhancement of their revenue, the advancement of agricultural output, and the modulation of the pricing structures for these commodities. Furthermore, subsidies are instrumental in offsetting the expenses associated with agricultural production.

Financial management in agricultural businesses is shaped by various factors that are unique to this sector compared to others. Subsidies play a significant role in achieving various economic and social goals. As a result, the question of their effectiveness and benefits naturally arises. Economists often examine whether subsidies lead to higher productivity and profitability and what mechanisms affect their efficiency. The agricultural sector is economically vulnerable as it is significantly influenced by both natural and economic factors. Since the price elasticity of supply is generally higher than the price elasticity of demand, agricultural production can experience significant fluctuations. Government subsidies are one of the tools that can contribute to stabilizing agricultural production and the agricultural market [

34,

35]. Various governments support the agricultural sector through subsidies to increase production for the domestic market or for export. In many countries, especially in developing areas, the farmers’ market is fragmented, meaning there are many producers with varying levels of productivity [

36].

Sha et al. [

12] conducted a comprehensive analysis of the effect of agricultural subsidies on the shared prosperity of farmers. Their findings indicated that subsidies play a significant role in boosting the income of rural households, narrowing income disparities, promoting overall development, and advancing the goal of common prosperity. However, the effect of financial support on shared prosperity differs based on factors such as political environments, natural conditions, economic development levels, and the size of agricultural enterprises across various regions. These factors play a key role in shaping costs and revenues, directly affecting the farm’s prosperity and success, which is reflected in its financial health. Conversely, the findings from the research conducted by Staniszewski and Borychowski [

24] supported the idea that the impact of subsidies on efficiency depends on the size of the farms. A statistically significant beneficial impact of subsidies was noted solely within the group of the largest farms. The authors of this investigation contend that their findings pose critical inquiries regarding the efficacy of the CAP in fostering the further advancement of the European agricultural model. Frýd and Sokol [

37] assert that the discourse surrounding agricultural subsidies within the European Union has persisted for an extended period. Nevertheless, even after extensive deliberation, it remains ambiguous whether these subsidies exert a positive or negative impact on agricultural efficiency. In the empirical section, they scrutinized a sample of Czech farms, and this analysis corroborated that the effect of subsidies is detrimental and varies according to the farm’s technical efficiency. Farms exhibiting higher efficiency experience a less distorting impact compared to those with lower efficiency. According to Minviel and Latruffe [

38], due to ongoing reforms in agricultural policies and the pressure on public finances, exploring the relationship between public subsidies and farm technical efficiency has become a key topic in production economics. Technical efficiency refers to a farm’s ability to utilize available technology effectively, meaning it either produces the highest possible output with a given set of inputs or uses the least number of inputs to achieve a specific level of output. Generally, public subsidies are not designed specifically to improve technical efficiency, but rather to boost production, support farmers’ incomes, or encourage the production of certain outputs, including environmental ones. However, if subsidies inadvertently reduce technical efficiency, it raises the question of whether there might be a more effective way to support farms. When providing subsidies, the issue of sustainability is also important, as the agricultural sector is crucial in the shift towards sustainability, since it can contribute to the protection of the climate and biodiversity but can also harm them. While some agricultural subsidies appear to be environmentally beneficial, the majority are considered environmentally harmful. The findings of the study by Heyl et al. [

39] suggest that agricultural subsidies should be significantly reduced and used only as supplementary tools, as other policy tools, like quantity control measures, are more effective in tackling the root causes of unsustainability, such as the consumption of fossil fuels and the practice of livestock farming. However, subsidies can still serve as useful supplementary tools for rewarding the provision of public goods, provided they are designed to avoid typical governance issues. Moreover, there is a need to enhance data collection and transparency, increase funding for research and development, and integrate environmental objectives into EU legislation to ensure that all agricultural subsidies are in line with global environmental goals.

Herda-Kopańska and Kulawik [

40] assert that subsidies associated with agricultural production constitute a prevalent mechanism of support across numerous nations, including those that are less developed and grappling with economic adversities in attaining food self-sufficiency, as well as in highly developed countries. The authors elucidate that during the transition from the 20th to the 21st century, this mode of support experienced a decline in favorability; however, within the second decade of the 21st century, it underwent a resurgence, commonly referred to as recoupling. The COVID-19 pandemic, along with the ongoing conflict between Ukraine and Russia, are pivotal factors that have augmented interest in the examination of the agricultural sector’s competitiveness, and these dynamics will substantially influence the future trajectory and interrelation of scholarly inquiries within this domain. Nevertheless, the pronounced alteration in the geopolitical landscape has underscored the necessity of not overlooking the original objectives of the primary sector. Conversely, it is imperative that concerted efforts are undertaken to systematically achieve these aims. Considering recent events in Ukraine, food self-sufficiency has become a top priority for individual European Union member states once again. Consequently, farm productivity should be regarded as a fundamental determinant in the judicious allocation of public support among agricultural producers [

18].

An intriguing investigation addressing the topic discussed was also conducted by Bernini and Galli [

41], whose results indicate that, alongside comprehending the influence of subsidies on the environmental and economic results of agriculture, it is imperative to examine both the direct and indirect mechanisms arising from CAP subsidies on farmers’ economic performance and environmental sustainability, with the objective of attaining enduring sustainability and competitiveness. In addition to their immediate effect on agricultural performance, subsidies can also affect farmers’ efficiency levels through inter-farmer relationships. An individual’s work motivation may be shaped by the practices of proximal farmers, leading to the dissemination of knowledge, analogous investment decisions, and collective choices in the adoption of more efficient methodologies. Consequently, farmers operating within the same region may emulate one another, and an individual farmer may realize efficiency enhancements by acquiring insights on resource utilization from neighboring farmers, resulting in shared business practices.

Based on the previous considerations, we can conclude that effective support for agriculture depends on the proper setting of subsidy policy, which must be tailored to the specific needs and problems of the sector in each country. While strengthening the first pillar may be useful in the case of low farm incomes, in the case of long-term structural problems, such as low production or deteriorating environmental conditions, attention should be directed towards investments and modernization. Such an approach will not only support family farms but also improve the overall competitiveness and sustainability of agriculture in the long term.

From the perspective of more efficient functioning of Slovak agriculture in the context of political recommendations, supporting family farms is justified. This recommendation is relevant because it is necessary to perceive business activities in the agricultural sector also in the context of social and cultural aspects. Supporting family farming is a crucial strategy for ensuring the long-term sustainability of this sector. Family farms play an invaluable role in the economy, as their operations are based on strong family ties, which positively influence their economic efficiency as well as the need to preserve the cultural and natural values of the respective regions. For this reason, it is necessary to support family farms not only through direct subsidies but also through investments in modernization and technological advancement, which will allow them to face long-term structural challenges.

5. Conclusions

Our study offers a deeper understanding of the competitiveness of Slovak farms up to 2019. EU financial support continues to be vital for boosting the competitiveness of Slovak farms. It offers crucial funding for innovation, infrastructure, sustainability, and rural development, allowing farms to increase productivity and adjust to shifting market conditions. However, issues such as the unequal distribution of support, reliance on subsidies, and competition from larger agricultural nations need to be tackled. By prioritizing innovation, sustainability, and market diversification, Slovak farms can enhance their competitiveness both within the European Union and globally. In our analyzed findings, this study provided the following conclusions. When testing the first hypothesis, a statistically significant correlation was confirmed between the competitiveness of agricultural enterprises and financial support through subsidies in all observed years and for the entire observed period, except for the year 2013. When testing the second hypothesis, it was also accepted, confirming the existence of statistically significant differences in the competitiveness of agricultural enterprises depending on whether they received subsidies or not.

These results need to be considered in light of the inherent limitations of this study. The main limitation is that the data are only available up to 2019, meaning they do not cover the period when Slovak agriculture was impacted by the recent external shocks, such as the military conflict in Ukraine and the energy crisis. Although data from 2020 onward were solicited from the MPRV SR, alterations in the methodology for data collection rendered it incompatible with the database established during the preceding period. Another limitation was related to the research sample, which, despite being large, faced difficulties in conducting the panel data analysis due to the 16-year period under study. During this time, some companies underwent changes in their legal structure or location, some shut down completely, and others were newly established.

The next phase of this research would aim to explore the competitiveness of Slovak farms, considering the effects of recent major external shocks, while also considering the conditions of the most recent CAP reform. In future research, after obtaining data from 2020 onwards from the MPRV SR, we aim to concentrate not only on the overall competitiveness but also on a thorough analysis of the most effective subsidy forms in the context of enhancing the competitiveness of the agricultural sector in Slovakia.