Intersectoral Linking of Agriculture, Hospitality, and Tourism—A Model for Implementation in AP Vojvodina (Republic of Serbia)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Models of Intersectoral Linkages in Tourism

2.2. Development of a Model for Intersectoral Linkages Between Agriculture, Hospitality, and Tourism in Vojvodina

2.3. Heterogeneity of Stakeholder Attitudes Toward Intersectoral Linkages in Tourism

2.4. Subjects Involved in Intersectoral Linkages in AP Vojvodina

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Researched Area

3.2. Research Model

3.3. Research Procedure and Instrument

3.4. Participants in the Research

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.2. Analysis and Validation of the Model—Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Model Fit Indices

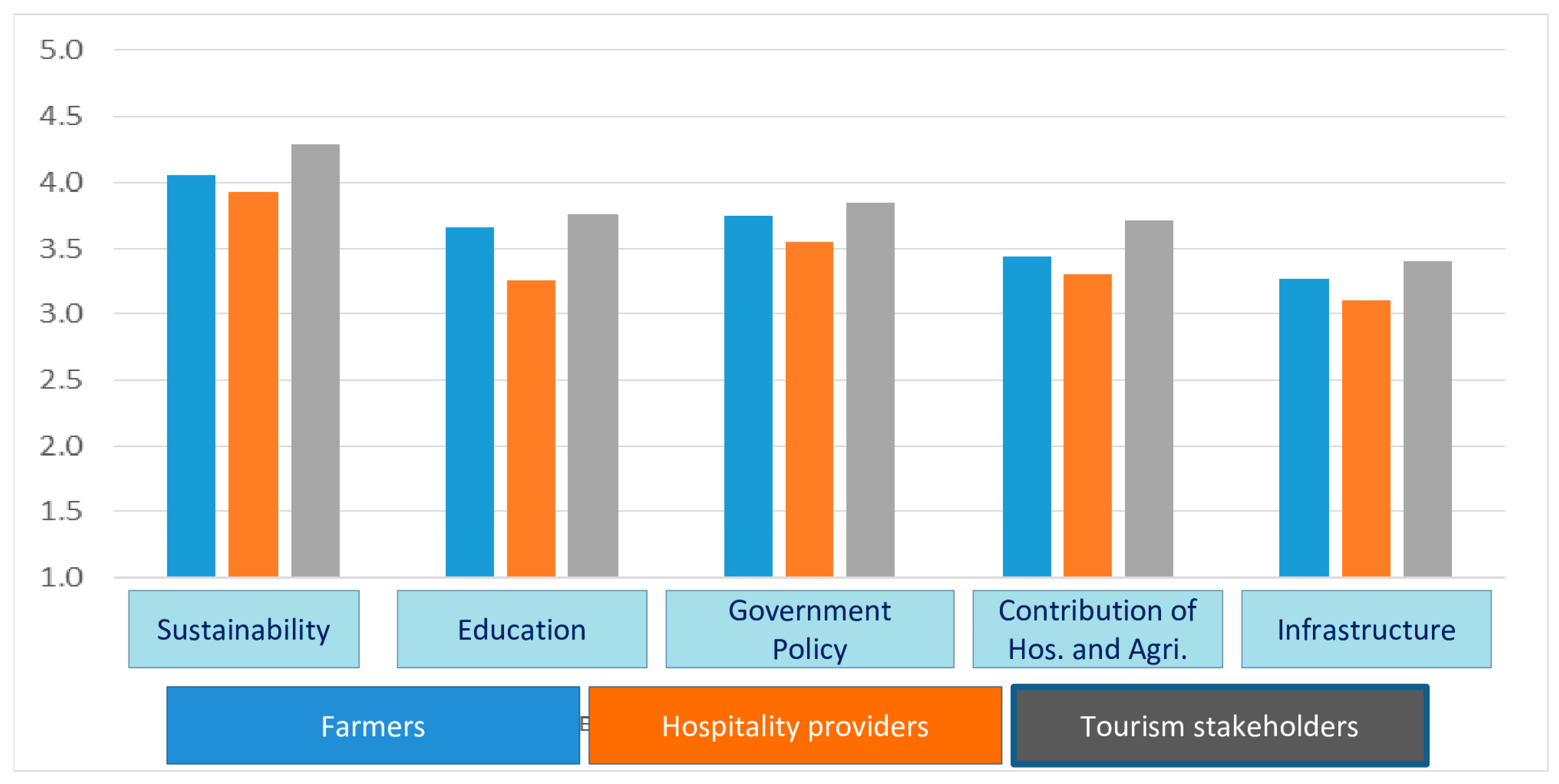

4.3. Analysis of Respondents’ Attitude Heterogeneity Toward Intersectoral Connection

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Socci, P.; Errico, A.; Castelli, G.; Penna, D.; Preti, F. Terracing: From Agriculture to Multiple Ecosystem Services. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Environ. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Venturi, M.; Agnoletti, M. Agricultural Heritage Systems and Landscape Perception among Tourists. The Case of Lamole, Chianti (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.A.; Yagüe, J.L.; De Nicolás, V.L.; Díaz-Puente, J.M. Characterization of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Valeri, M.; Shekhar. Understanding the relationship among factors influencing rural tourism: A hierarchical approach. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2022, 35, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D.; Mossberg, L.; Therkelsen, A. Food and tourism synergies: Perspectives on consumption, production and destination development. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, M.A.; Law, R.; Cagri Dogan, I. Exploring the social structure of strategic management research with a hospitality industry focus. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 1, 436–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachao, S.; Breda, Z.; Fernandes, C.; Joukes, V. Food tourism and regional development: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiao, Y. Planning island sustainable development policy based on the theory of ecosystem services: A case study of Zhoushan Archipelago, East China. Isl. Stud. J. 2020, 15, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santeramon, F.G.; Seccia, A.; Nardone, G. The synergies of the Italian wine and tourism sectors. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 6, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, F.; Botti, A.; Grimaldi, M.; Monda, A.; Vesci, M. Social innovation in smart tourism ecosystems: How technology and institutions shape sustainable value co-creation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adongo, R.; Choe, J.Y.; Han, H. Tourism in Hoi An, Vietnam: Impacts, perceived benefits, community attachment and support for tourism development. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2017, 17, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.G.; Neuhofer, B. Airbnb—An exploration of value co-creation experiences in Jamaica. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2361–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulauskaite, D.; Powell, R.; Coca-Stefaniak, A.; Morrison, A. Living like a local: Authentic tourism experiences and the sharing economy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckert, M.; Peters, M.; Pilz, G. The co-creation of host–guest relationships via couchsurfing: A qualitative study. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.C.; Mendes, J.; Do Valle, P.O.; Scott, N. Co-creation of tourist experiences: A literature review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truțescu, M.N.; Rotarus, A. Approach on sustainable development through the involvement of local community in tourism food industry: A case study of Azuga resort, Romania. J. Environ. Tour. 2018, 8, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.; Getz, D.; Dolnicar, S. Food tourism subsegments: A data-driven analysis. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugosi, P. Developing and Publishing Interdisciplinary Research: Creating Dialogue, Taking Risks. Hosp. Soc. 2020, 10, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugosi, P. Exploring the hospitalitytourism nexus: Directions and questions for past and future research. Tour. Stud. 2021, 21, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islahuddin, I.; Akib, H.; Eppang, B.M.; Salim, M.A.M.; Darmayasa, D. Reconstruction of the actor collaboration model in the development of marine tourism destinations in the new normal local economy. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2021, 5, 1505–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, K.B.; Joshi, B.R. Community Collaboration with Tourism Stakeholders: Issues and Challenges to Promote Sustainable Community Development in Annapurna Sanctuary Trail, Nepal. Saudi J. Eng. Technol. 2023, 8, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenfeld, A.; Hall, C.M. Tourism and innovation: A cross sectoral and interregional perspective. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 652–664. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, P.; Song, H. Multiple Effects of Agricultural Cultural Heritage Identity on Residents’ Value Co-Creation—A Host–Guest Interaction Perspective on Tea Culture Tourism in China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W. Linkages between tourism and agriculture for inclusive development in Tanzania: A value chain perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2018, 1, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipokusumo, B.; Sjah, T. Key sectors and inter-sectoral linkages in economic development in East Lombok Regency, West Nusa Tenggara Province. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 681, 012062. [Google Scholar]

- Tchouamou Njoya, E.; Nikitas, A. Assessing agriculture–tourism linkages in Senegal: A structure path analysis. GeoJournal 2020, 85, 1469–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihoglu, G.; Gezici, F. Linkages Between Tourism and Agriculture: The Case of Turkey. In Regional Science Perspectives on Tourism and Hospitality; Ferrante, M., Fritz, O., Öner, Ö., Eds.; Advances in Spatial Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizou, E.; Karelakis, C.; Galanopoulos, K.; Mattas, K. The role of agriculture as a development tool for a regional economy. Agric. Syst. 2020, 173, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sych, V.; Yavorska, V.; Kolomiyets, K. Formation of regional inter-sectoral complexes of recreation and tourism activity as a sign of structural reorganization of the economy. J. Educ. Health Sport 2021, 11, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Sastri, R.; Edziah, B.K.; Setiyawan, A. Exploring the inter-sectoral and inter-regional effect of tourism industry in Indonesia based on input-output framework. Kybernetes 2024. ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjac, M. Sinergija poljoprivrede i ugostiteljstva u funkciji razvoja turizma u Vojvodini. In Faculty of Sciences; University of Novi Sad: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2022. Available online: https://nardus.mpn.gov.rs/handle/123456789/20574 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Novković, N.; Vukelić, N.; Mutavdžić, B.; Tekić, D. Development Opportunities of Agribusiness in the AP Vojvodina. Contemp. Agric. 2023, 72, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tešanović, D.; Banjac, M.; Radivojević, G.; Stanković, A. The influence of local agriculture in tourism development. In Proceedings of the Contemporary Trends in Tourism and Hospitality 2019, Get Ready for iGeneration, Novi Sad, Serbia, 12–13 September 2019; pp. 62–63, ISBN 978-86-7031-519-8. [Google Scholar]

- Banjac, M.; Tešanović, D.; Dević Blanuša, J. Importance of connection between agricultural holding and catering facilities in development of tourism in Vojvodina. In Proceedings of the Međunarodni Naučni Skup “Nauka i Praksa Poslovnih Studija”, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 15 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tešanović, D.; Kalenjuk, B.; Banjac, M. Food and tourism synergy-inpact on sustainable development of the region. In Proceedings of the Jahorina Business Forum 2018, Sustainable Tourism and Institutional Environment, Jahorina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 22–24 March 2017; pp. 209–213, ISSN 2303-8969. [Google Scholar]

- Novaković, T.; Mutavdžić, B.; Milić, D.; Tekić, D. Analysis of the subsidy structure in agriculture of Vojvodina. J. Process. Energy Agric. 2019, 23, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategija Razvoja Turizma R. Srbije 2016–2025. Available online: https://mto.gov.rs/extfile/sr/207/strategija.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Strategija Razvoja Poljoprivrede i Ruralnih Područja 2014–2024. Available online: https://pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/strategija/2014/85/1 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Grubor, B.; Banjac, M.; Đerčan, B.; Tešanović, D.; Šmugović, S.; Radivojević, G.; Ivanović, V.; Vujasinović, V.; Stošić, T. The Sustainability of Gastronomic Heritage and Its Significance for Regional Tourism Development. Heritage 2023, 6, 3402–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmugović, S.; Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Ivanović, V.; Tešanović, D.; Novaković, D.; Marić, A.; Lazarević, J.; Paunić, M. The Effects of the Characteristics of Catering Establishments and Their Managers on the Offering of Dishes Prepared with Traditional Food Products in Bačka Region, Serbia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirić, M.; Tešanović, D.; Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Ćirić, I.; Banjac, M.; Radivojević, G.; Grubor, B.; Tošić, P.; Simović, O.; Šmugović, S. Analyses of the Attitudes of Agricultural Holdings on the Development of Agritourism and the Impacts on the Economy, Society and Environment of Serbia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.; Memery, J. Tourists, local food and the intention-behaviour gap. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Sasaki, N.; Shivakoti, G.; Zhang, Y. Effective governance in tourism development—An analysis of local perception in the Huangshan mountain area. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Sasaki, N.; Jourdain, D.; Kim, S.M.; Shivakoti, P.G. Local livelihood under different governances of tourism development in China: A case study of Huangshan mountain area. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, G.; Vieri, S. Cultural and rural tourism: Potential synergies for a new economic development pattern. The Italian case. Cactus Tour. J. 2018, 18, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Broccardo, L.; Culasso, F.; Truant, E. Unlocking Value Creation Using an Agritourism Business Model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, S.; Rahayu, E.S.; Riani, A.L.; Suminah, S.; Udin, U.D.I.N. Empowerment model for sustainable tourism village in an emerging country. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choya, K.L.; Leea, W.B.; Lob, V. Design of an intelligent supplier relationship management system: A hybrid case based neural network approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2003, 24, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson-Ngwenya, P.; Momsen, J. Tourism and agriculture in Barbados: Changing relationships. In Tourism and Agriculture; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, M. The Development of an E Elopment of an Eco-Gastro-Gastronomic Tourism (egt) Supply Tourism (egt) Supply Chain-Analyzing Linkages Between Farmer, Restaurants, and Tourists in Aruba; University of Central Florida: Orlando, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pavluković, V.; Kovačić, S.; Pavlović, D.; Stankov, U.; Cimbaljević, M.; Panić, A.; Radojević, T.; Pivac, T. Tourism destination competitiveness: An application model for Serbia. J. Vac. Mark. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesen, M.; Sundbo, D.; Sundbo, J. Local food and tourism: An entrepreneurial network approach. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J. A dynamic model of sustainable tourism. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidali, K.L.; Hemmerling, S. Developing an authenticity model of traditional food specialties: Does the self-concept of consumers matter? Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, N.; Babović, M. Radna Snaga i Aktivnosti Poljoprivrednih Gazdinstava [Labour Force and Activities of Agricultural Holdings]; Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bubalo-Živković, M.; Kalenjuk, B.; Lukić, T.; Đerčan, B. Who Is Still Engaged in Agriculture in Vojvodina? Eur. Geogr. Stud. 2018, 5, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Đerčan, B.; Gatarić, D.; Bubalo-Živković, M.; Belij Radin, M.; Vukoičić, D.; Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Lukić, T.; Vasić, P.; Nikolić, M.; Lutovac, M.; et al. Evaluating farm tourism development for sustainability: A case study of farms in the peri-urban area of Novi Sad (Serbia). Sustainability 2023, 15, 12952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republički Zavod za Statistiku. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.rs/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Šmugović, S.; Tekić, D.; Ivanović, V.; Novaković, A.; Tešanović, D.; Banjac, M.; Đerčan, B.; Peulić, T.; Mutavdžić, B.; et al. Characteristics of traditional food products as a segment of sustainable consumption in Vojvodina’s hospitality industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubor, B.; Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Đerčan, B.; Tešanović, D.; Banjac, M.; Lukić, T.; Živković, M.B.; Udovičić, D.I.; Šmugović, S.; Ivanović, V.; et al. Traditional and authentic food of ethnic groups of Vojvodina (Northern Serbia)—Preservation and potential for tourism development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuksanović, N.; Tešanović, D.; Kalenjuk, B.; Portić, M. Gender, age and education differences in food consumption within a region: Case studies of Belgrade and Novi Sad (Serbia). Acta Geogr. Slov. 2019, 59, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichholzer, G. The Delphi method: Eliciting experts’ knowledge in technology foresight. In Interviewing Experts; Bogner, A., Littig, B., Menz, W., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doke, E.R.; Swanson, N.E. Decision variables for selecting prototyping in information systems development: A Delphi study of MIS managers. Inf. Manag. 1995, 29, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulmoski, G.J.; Hartman, F.T.; Krahn, J. The Delphi method for graduate research. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2007, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, L.M. Pilot studies. Medsurg. Nurs. 2008, 17, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Little, R.J.A.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, D. Statistical Methods for Psychology, 8th ed.; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, B.P. SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2000, 32, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Widaman, K.F.; Preacher, K.J.; Hong, S. Sample size in factor analysis: The role of model error. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2001, 36, 611–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.H. The Structural Equation Modeling Approach: Basic Concepts and Fundamental Issues. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications, 1st ed.; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 1995; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches-Pereira, A.; Onguglo, B.; Pacini, H.; Gómez, M.F.; Coelho, S.T.; Muwanga, M.K. Fostering local sustainable development in Tanzania by enhancing linkages between tourism and small-scale agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1567–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurić, K. Poljoprivreda i Ruralni Razvoj Srbije u Procesu Evropskih Integracija; Poljoprivredni Fakultet, Univerzitet u Novom Sadu: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cvijanović, D.; Subić, J.; Paraušić, V. Poljoprivredna Gazdinstva Prema Ekonomskoj Veličini i Tipu Proizvodnje u Republici Srbiji; Republički Zavod za Statistiku: Belgrade, Serbia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, X.Y. Networking and collaboration between tourism and agriculture: Food tourism experiences along the National Tourist Routes of Norway. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Zhou, Z.; Kim, D.-J. A new path of sustainable development in traditional agricultural areas from the perspective of open innovation—A coupling and coordination study on the agricultural industry and the tourism industry. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojević, J.; Krstić, B. Intersectoral linkages and their contribution to economic growth in the Republic of Serbia. Facta Univ. 2019, 16, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsouris, A.; Gidarakou, I.; Grava, F.; Michailidis, A. The phantom of (agri)tourism and agriculture symbiosis? A Greek case study. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 12, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y. Assessing managerial efficiency of educational tourism in agriculture: Case of dairy farms in Japan. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Álvarez, F.J.; del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C.; Álvarez-García, J.; Durán-Sánchez, A. Limitations of Rural Tourism as an Economic Diversification and Regional Development Instrument. The Case Study of the Region of La Vera. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample 1 | |||

| Description of the Sample | Agricultural Sector n = 94 | Hospitality Sector n = 101 | Tourism Sector n = 101 |

| Age | |||

| min-max (years old) | 21–82 | 18–72 | 18–71 |

| AS (SD) | 50.12 (13.05) | 34.45 (11.55) | 37.22 (10.30) |

| Gender | |||

| men | 67 (71.3%) | 67 (66.3%) | 55 (54.5%) |

| women | 27 (28.7%) | 34 (33.7%) | 46 (45.5%) |

| Highest level of completed education | |||

| elementary school | 15 (16.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0% |

| high school | 60 (63.8%) | 49 (48.5%) | 28 (27.7%) |

| college | 6 (6.4%) | 30 (29.7%) | 28 (27.7%) |

| university | 13 (13.8%) | 22 (21.8%) | 45 (44.6%) |

| Please indicate how many years you have been in agriculture, hospitality, and tourism (years) | 1–65 | 1–40 | 1–39 |

| AS (SD) | 21.98 (14.26) | 11.69 (8.19) | 18.90 (10.60) |

| Sample 2 | |||

| Description of the Sample | Agricultural Sector n = 94 | Hospitality Sector n = 100 | Tourism Sector n = 100 |

| Age | |||

| min-max (years old) | 20–84 | 17–73 | 17–73 |

| AS (SD) | 49.53 (13.21) | 33.96 (11.70) | 36.77 (10.45) |

| Gender | |||

| men | 68 (72.3%) | 66 (66.0%) | 53 (53.0%) |

| women | 26 (27.7%) | 34 (34.0%) | 47 (47.0%) |

| Highest level of completed education | |||

| elementary school | 15 (16.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| high school | 61 (64.9%) | 49 (49.0%) | 28 (28.0%) |

| college | 6 (6.4%) | 30 (30.0%) | 28 (28.0%) |

| university | 12 (12.7%) | 21 (21.0%) | 44 (44.0%) |

| Please indicate how many years you have been in agriculture, hospitality, and tourism (years) | 1–65 | 1–40 | 1–39 |

| AS (SD) | 21.98 (14.26) | 11.69 (8.19) | 18.90 (10.60) |

| No. of Factors | Initial Values | After Extraction | λ After Rotation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel Analysis | Λ | % of Variance | Cumulative % | % Variances | Cumulative % | ||

| 1 | 1.62 | 11.815 | 31.025 | 31.025 | 28.732 | 28.732 | 10.102 |

| 2 | 1.53 | 2.745 | 7.214 | 38.239 | 5.689 | 34.421 | 6.725 |

| 3 | 1.47 | 1.682 | 4.375 | 42.614 | 2.845 | 37.266 | 6.785 |

| 4 | 1.42 | 1.542 | 3.995 | 46.609 | 2.562 | 39.828 | 5.821 |

| 5 | 1.38 | 1.421 | 3.725 | 50.334 | 2.194 | 42.022 | 1.604 |

| 6 | 1.35 | 1.262 | 3.330 | 53.664 | |||

| Items | Loadings |

|---|---|

| Intersectoral collaboration contributes to increasing revenue from tourism, agriculture, and hospitality. | 0.77 |

| Investing in intersectoral cooperation brings economic benefits to the local community. | 0.90 |

| Intersectoral collaboration can contribute to improving the standard of living of local communities. | 0.46 |

| Tourism and agriculture together contribute to employment in rural areas. | 0.74 |

| Sustainable intersectoral cooperation can help preserve traditional skills and cultural values. | 0.52 |

| Intersectoral collaboration between tourism, agriculture, and hospitality helps in preserving natural resources. | 0.38 |

| Preserving local customs and traditions should be a priority in tourism development. | 0.39 |

| Through intersectoral cooperation, the authenticity of the destination can be preserved. | 0.41 |

| Improving infrastructure in tourism and agriculture positively affects intersectoral collaboration. | 0.55 |

| Technological innovations can contribute to the sustainable development of tourism in the region. | 0.63 |

| Well-established communication between sectors is key to successful intersectoral cooperation. | 0.79 |

| Collaboration between farmers, hoteliers, and tourism stakeholders reduces operating costs in all sectors. | 0.68 |

| Investing in transportation and communication networks is essential for the development of intersectoral cooperation. | 0.73 |

| Transparency in operations can improve collaboration among different sectors. | 0.67 |

| Lack of flexibility in business models hampers intersectoral cooperation. | 0.63 |

| There is a lack of trust between farmers, hoteliers, and tourism stakeholders. | 0.55 |

| The use of environmentally friendly methods in production is a necessity in tourism development. | 0.57 |

| Items | Loadings |

|---|---|

| There is a need for organizing educational programs that connect farmers, hoteliers, and tourism stakeholders. | 0.38 |

| There is insufficient education on how intersectoral collaboration can contribute to sustainable tourism development in our region. | 0.56 |

| There is a need for organizing educational programs that connect farmers, hoteliers, and tourism stakeholders. | 0.35 |

| Education on sustainable practices in tourism should be part of training for all sector actors. | 0.80 |

| Farmers and hoteliers should be introduced to new technologies and methods that support the sustainability of tourism. | 0.49 |

| Farmers, hoteliers, and tourism stakeholders should participate in joint workshops and seminars that support intersectoral cooperation. | 0.35 |

| Exchange of experiences and best practices among stakeholders from different sectors can improve intersectoral collaboration. | 0.46 |

| Tourism workers need additional training to learn how to communicate better with farmers and hoteliers. | 0.48 |

| Introducing joint educational sessions can contribute to better collaboration between sectors. | 0.36 |

| Items | Loadings |

|---|---|

| Government policies should encourage greater private sector involvement in the development of tourism, agriculture, and hospitality. | 0.38 |

| The government should provide more support to local communities in developing intersectoral collaboration that includes agriculture, hospitality, and tourism. | 0.50 |

| The government should develop specific policies that encourage intersectoral collaboration between agriculture, hospitality, and tourism. | 0.79 |

| Government subsidies and financial incentives should be available to farmers, hoteliers, and tourism stakeholders to encourage them to engage in intersectoral collaboration. | 0.78 |

| Items | Loadings |

|---|---|

| There is a disagreement between farmers and hoteliers regarding the prices and quality of products used in tourism. | 0.62 |

| Hoteliers believe that intersectoral linking can improve their business model and attract more tourists. | 0.51 |

| Hoteliers expect greater consistency in product quality from farmers to enhance the tourism offering. | 0.68 |

| There is a disagreement between farmers and hoteliers regarding the constant availability of products on the hospitality and tourism market. | 0.64 |

| Farmers and hoteliers recognize the importance of intersectoral collaboration for the development of sustainable tourism. | 0.39 |

| Items | Loadings |

|---|---|

| Infrastructure for the direct sale of local products is not sufficiently developed to support tourism. | 0.50 |

| There is a need for infrastructure projects that would enable the promotion and distribution of local products as tourist attractions. | 0.38 |

| Scales of the Questionnaire | AS | SD | α | MIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | 4.09 | 0.62 | 0.92 | 0.41 |

| Education | 3.56 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 0.32 |

| Government Policy | 3.71 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.42 |

| Contribution of Hospitality and Agriculture | 3.48 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.34 |

| Infrastructure | 3.26 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.43 |

| Fit Index | Value | Recommended Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square (χ2, p-value) | 312.45 (p = 0.06) | p > 0.05 (ideal) | The model fits the data well. |

| CFI (Comparative Fit Index) | 0.93 | ≥0.90 (good), ≥0.95 (excellent) | The model shows a high degree of alignment. |

| TLI (Tucker–Lewis Index) | 0.91 | ≥0.90 (good), ≥0.95 (excellent) | The model has an adequate structure. |

| RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) | 0.05 | ≤0.08 (good), ≤0.05 (excellent) | The model shows minimal error. |

| SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Residual) | 0.06 | ≤0.08 (good) | The model is consistent with the data. |

| Item | Sustainability | Education | Government Policy | Contribution | Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1 | 0.79 | - | - | - | - |

| s2 | 0.77 | - | - | - | - |

| s3 | 0.74 | - | - | - | - |

| s4 | 0.71 | - | - | - | - |

| s5 | 0.78 | - | - | - | - |

| s6 | 0.76 | - | - | - | - |

| s7 | 0.80 | - | - | - | - |

| s8 | 0.74 | - | - | - | - |

| s9 | 0.73 | - | - | - | - |

| s10 | 0.79 | - | - | - | - |

| s11 | 0.81 | - | - | - | - |

| s12 | 0.77 | - | - | - | - |

| s13 | 0.76 | - | - | - | - |

| s14 | 0.78 | - | - | - | - |

| s15 | 0.75 | - | - | - | - |

| s16 | 0.80 | - | - | - | - |

| s17 | 0.77 | - | - | - | - |

| s18 | - | 0.82 | - | - | - |

| s19 | - | 0.79 | - | - | - |

| s20 | - | 0.76 | - | - | - |

| s21 | - | 0.75 | - | - | - |

| s22 | - | 0.78 | - | - | - |

| s23 | - | 0.79 | - | - | - |

| s24 | - | 0.81 | - | - | - |

| s25 | - | 0.77 | - | - | - |

| s26 | - | 0.75 | - | - | - |

| s27 | - | - | 0.70 | - | - |

| s28 | - | - | 0.72 | - | - |

| s29 | - | - | 0.75 | - | - |

| s30 | - | - | 0.76 | - | - |

| s31 | - | - | - | 0.74 | - |

| s32 | - | - | - | 0.78 | - |

| s33 | - | - | - | 0.80 | - |

| s34 | - | - | - | 0.77 | - |

| s35 | - | - | - | 0.75 | - |

| s36 | - | - | - | - | 0.71 |

| s37 | - | - | - | - | 0.69 |

| Factor | Sustainability | Education | Government Policy | Contribution | Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.47 |

| Education | 0.58 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.45 |

| Government Policy | 0.50 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.46 |

| Contribution of Hospitality and Agriculture | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| Infrastructure | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| Dimensions | F (2,586) | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | 18.68 | 0.000 | 0.06 |

| Education | 34.46 | 0.000 | 0.11 |

| Government Policy | 8.00 | 0.000 | 0.03 |

| Contribution of Hospitality and Agriculture | 17.27 | 0.000 | 0.06 |

| Infrastructure | 4.51 | 0.011 | 0.02 |

| Dependent Variable | (I) Group | (J) Group | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | 1.00 farmers | 2.00 hospitality providers | 0.13073 | 0.06086 | 0.096 |

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | −0.23011 | 0.06086 | 0.001 | ||

| 2.00 hospitality providers | 1.00 farmers | −0.13073 | 0.06086 | 0.096 | |

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | −0.36084 | 0.05975 | 0.000 | ||

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | 1.00 farmers | 0.23011 | 0.06086 | 0.001 | |

| 2.00 hospitality providers | 0.36084 | 0.05975 | 0.000 | ||

| Education | 1.00 farmers | 2.00 hospitality providers | 0.41511 | 0.06620 | 0.000 |

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | −0.09298 | 0.06620 | 0.482 | ||

| 2.00 hospitality providers | 1.00 farmers | −0.41511 | 0.06620 | 0.000 | |

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | −0.50808 | 0.06499 | 0.000 | ||

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | 1.00 farmers | 0.09298 | 0.06620 | 0.482 | |

| 2.00 hospitality providers | 0.50808 | 0.06499 | 0.000 | ||

| Government Policy | 1.00 farmers | 2.00 hospitality providers | 0.19108 | 0.07498 | 0.033 |

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | −0.09872 | 0.07498 | 0.565 | ||

| 2.00 hospitality providers | 1.00 farmers | −0.19108 | 0.07498 | 0.033 | |

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | −0.28980 | 0.07362 | 0.000 | ||

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | 1.00 farmers | 0.09872 | 0.07498 | 0.565 | |

| 2.00 hospitality providers | 0.28980 | 0.07362 | 0.000 | ||

| Contribution of Hospitality and Agriculture | 1.00 farmers | 2.00 hospitality providers | 0.14129 | 0.07082 | 0.140 |

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | −0.26170 | 0.07082 | 0.001 | ||

| 2.00 hospitality providers | 1.00 farmers | −0.14129 | 0.07082 | 0.140 | |

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | −0.40299 | 0.06953 | 0.000 | ||

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | 1.00 farmers | 0.26170 | 0.07082 | 0.001 | |

| 2.00 hospitality providers | 0.40299 | 0.06953 | 0.000 | ||

| Infrastructure | 1.00 farmers | 2.00 hospitality providers | 0.15258 | 0.10128 | 0.397 |

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | −0.14593 | 0.10128 | 0.450 | ||

| 2.00 hospitality providers | 1.00 farmers | −0.15258 | 0.10128 | 0.397 | |

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | −0.29851 | 0.09944 | 0.008 | ||

| 3.00 tourism stakeholders | 1.00 farmers | 0.14593 | 0.10128 | 0.450 | |

| 2.00 hospitality providers | 0.29851 | 0.09944 | 0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paunić, M.; Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Tešanović, D.; Ivanović, V.; Vujasinović, V.; Gagić Jaraković, S.; Vulić, G.; Ćirić, M. Intersectoral Linking of Agriculture, Hospitality, and Tourism—A Model for Implementation in AP Vojvodina (Republic of Serbia). Agriculture 2025, 15, 604. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060604

Paunić M, Kalenjuk Pivarski B, Tešanović D, Ivanović V, Vujasinović V, Gagić Jaraković S, Vulić G, Ćirić M. Intersectoral Linking of Agriculture, Hospitality, and Tourism—A Model for Implementation in AP Vojvodina (Republic of Serbia). Agriculture. 2025; 15(6):604. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060604

Chicago/Turabian StylePaunić, Maja, Bojana Kalenjuk Pivarski, Dragan Tešanović, Velibor Ivanović, Vesna Vujasinović, Snježana Gagić Jaraković, Gordana Vulić, and Miloš Ćirić. 2025. "Intersectoral Linking of Agriculture, Hospitality, and Tourism—A Model for Implementation in AP Vojvodina (Republic of Serbia)" Agriculture 15, no. 6: 604. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060604

APA StylePaunić, M., Kalenjuk Pivarski, B., Tešanović, D., Ivanović, V., Vujasinović, V., Gagić Jaraković, S., Vulić, G., & Ćirić, M. (2025). Intersectoral Linking of Agriculture, Hospitality, and Tourism—A Model for Implementation in AP Vojvodina (Republic of Serbia). Agriculture, 15(6), 604. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060604