Abstract

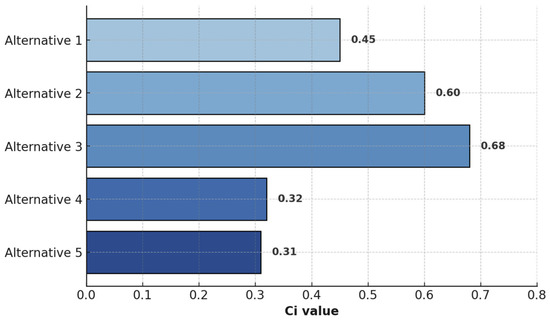

Rural tourism and agritourism are essential drivers of sustainable economic development in mountain regions, generating income opportunities while preserving cultural and natural heritage. The North-West region of Romania has significant potential in this sector. Yet, tourism development is unevenly distributed, and the integration of local economic activities remains limited, an imbalance that reduces the overall impact of tourism on regional sustainability and economic resilience. To assess viable strategies for agritourism development, the study applies the TOPSIS method, evaluating four key criteria: infrastructure accessibility, diversity of tourism experiences, service quality, and long-term economic sustainability. A survey was conducted with 102 respondents, and the collected data were analyzed using the TOPSIS framework to determine the most effective development approaches. The findings indicated that the ecotourism trails represent the most favorable strategy (Ci = 0.678), followed by promoting local products within tourism (Ci = 0.602) and expanding rural guesthouses (Ci = 0.467). In contrast, integrated tourism packages and tourist information centers ranked lower, suggesting that infrastructure investment and the strategic use of local resources should be prioritized. These insights provide practical recommendations for policymakers, investors, and local stakeholders, emphasizing the need for targeted support in ecotourism and rural economic initiatives. Furthermore, the study contributes to academic research by offering a structured, replicable approach to evaluating rural tourism development. By highlighting sustainable investment directions, the findings support efforts to enhance Romania’s rural tourism competitiveness while fostering economic growth in mountain regions.

1. Introduction

Agritourism represents a strategic approach to economic development, integrating sustainability principles with preserving natural and cultural heritage [1]. In mountain regions, where traditional economic activities face limitations due to geographical constraints and insufficient infrastructure, agritourism emerges as a viable alternative because it stimulates local economies and diversifies income sources for rural communities. By promoting regional identity through authentic products and traditions, agritourism helps mitigate rural depopulation and reduces socioeconomic disparities between urban and rural areas [2]. Experiences of European countries such as Austria, Switzerland, and Italy demonstrate that mountain regions can evolve into competitive tourism destinations when supported by coherent policies and targeted investments [3,4]. These countries have successfully transformed rural mountain villages into vibrant economic hubs by capitalizing on their natural and cultural assets while ensuring environmental sustainability. On the other hand, in Romania, although the potential for agritourism is considerable, its development remains uneven, considering the factors that influence this situation, such as infrastructure accessibility, the diversification of tourism services, and also the capacity of local communities to innovate and adapt to market demands [5]. Recent studies highlight that the long-term success of agritourism depends on its ability to provide authentic and immersive experiences deeply connected to the local environment and traditions [6,7,8]. Equally important is the active involvement of local populations in shaping and managing tourism initiatives. Also, it is important to specify that beyond its economic benefits, agritourism contributes to biodiversity conservation and the revitalization of marginalized rural areas, positioning itself as a fundamental pillar of sustainable regional development policies.

The North-West region of Romania, comprising the counties of Maramureș, Bihor, Bistrița-Năsăud, Cluj, and Sălaj, possesses considerable agritourism potential due to a distinctive mix of unspoiled mountain landscapes, well-preserved rural settlements, and a rich cultural heritage that continues to attract both domestic and international visitors. This region offers a diverse range of agritourism opportunities, rooted in the valorization of local traditions, craftsmanship, and sustainable rural lifestyles. Maramureș, for instance, is internationally recognized for its UNESCO-listed wooden churches and deeply rooted artisanal traditions [9], while Cluj and Bihor provide extensive mountain trails and ecotourism assets that further enrich the region’s appeal [10]. Despite its strengths, agritourism development across the region remains highly uneven. Some locations, such as Răchițele in Cluj and Stâna de Vale in Bihor, have benefited from targeted infrastructure investments and sustained promotional efforts, transforming them into well-established tourist hubs [11]. However, many rural communities continue to face structural limitations, including insufficient infrastructure, underutilized tourism resources, and restricted market access, disparities that are highlighting the pressing need for a strategic and integrated approach to agritourism development, ensuring that investments are directed toward initiatives with the highest potential for economic and social impact. The examining process of this region provides valuable insights into how agritourism can serve as a mechanism for reducing rural-urban development disparities while safeguarding cultural and natural heritage. A thorough analysis of successful agritourism models, coupled with an assessment of the barriers facing less developed areas, can inform the design of tailored policies and strategies, an approach that would foster a more balanced and sustainable economic trajectory for the entire region, maximizing the long-term benefits of agritourism for local communities. A major obstacle regarding the effective development of agritourism in Romania’s northwest region is the lack of a well-defined, data-driven strategy that takes into account both tourist expectations and the specific challenges faced by local entrepreneurs [12].

Although the region possesses substantial agritourism potential, many initiatives operate in isolation, lacking coordination and long-term strategic direction, fragmentation that leads to inefficient resource utilization, and deepening developmental disparities among rural communities, limiting the sector’s overall impact [13]. In light of these aspects, the research aims to address these gaps by identifying and analyzing the key priorities necessary for sustainable agritourism growth in the region. In this context, the research is guided by three central questions:

- -

- What are the primary priorities for agritourism development in the region, considering both the needs of tourists and the local resources available?

- -

- How can financial, human, and material resources be allocated more effectively to maximize agritourism’s economic and social benefits?

- -

- Which development strategies offer the highest potential for success, and what structural or operational challenges hinder their implementation?

To provide a structured and objective analysis, we decided to employ the TOPSIS method (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution), a multi-criteria decision-making approach [14]. This method enables the ranking of development alternatives based on economic impact, environmental sustainability, and community involvement. By applying this analytical framework, the research offers a practical tool for policymakers and local stakeholders, facilitating strategic resource allocation and identifying high-impact projects that can drive balanced and sustainable agritourism development.

1.1. The Main Purpose of the Research

The main purpose of the research is to assess and prioritize strategic agritourism development alternatives in the mountainous areas of Romania’s North-West region by applying the TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) method. The research seeks to identify the key factors influencing agritourism growth, determine the most effective investment strategies, and provide data-driven recommendations for policymakers, investors, and local stakeholders.

By systematically ranking development alternatives based on infrastructure accessibility, diversity of tourism offerings, service quality, environmental sustainability, and economic feasibility, the study aims to offer an objective framework for decision-making. The ultimate goal is to contribute to the sustainable growth of rural tourism, ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently, local economies are strengthened, and agritourism initiatives align with regional development priorities.

The research employs the TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) method, a multi-criteria decision-making approach to evaluate and rank agritourism development alternatives in Romania’s North-West mountain region. The methodology integrates primary data from stakeholder surveys (guesthouse owners, farmers, local authorities, and tourists) and secondary data from official tourism reports and statistical sources. Four key evaluation criteria—infrastructure accessibility, diversity of tourism offerings, quality of services, and economic sustainability—were weighted based on stakeholder input. The TOPSIS model systematically ranks development alternatives through data normalization, weighting, and distance calculations from ideal and anti-ideal solutions. This approach ensures objective prioritization of investment strategies, providing policy recommendations for decision-makers, investors, and local communities to enhance agritourism growth in a sustainable and economically viable manner.

1.2. Originality of the Research

Existing studies on agritourism in Romania predominantly adopt descriptive approaches, focusing on broad assessments of tourism potential or qualitative evaluations of visitor experiences [15,16,17,18,19,20]. While these contributions offer valuable insights, they often lack structured, data-driven frameworks to guide investment decisions and policy formulation. In contrast, this study introduces a quantitative analytical perspective, applying the TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) method, a well-established multi-criteria decision-making tool widely used in economic analysis but rarely explored in the context of Romanian rural tourism. By employing this approach, the research provides a systematic and objective mechanism for evaluating and ranking agritourism development alternatives, addressing a significant gap in the existing literature.

A key element of originality lies in the study’s methodological framework, which extends beyond the traditional expert-based approach commonly used in similar analyses [21,22,23,24,25]. Instead of relying solely on a narrow expert perspective, this research integrates insights from a diverse respondent base, including agritourism guesthouse owners, farmers, tourists, and local government representatives. This broader participation ensures a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the sector, enhancing the reliability and applicability of findings. The use of a structured survey targeting heterogeneous stakeholders strengthens the empirical foundation of the study, allowing for the identification and prioritization of actionable solutions based on economic viability and long-term sustainability.

By bridging theoretical research with practical applications, this study offers a valuable tool for policymakers, investors, and rural entrepreneurs, facilitating evidence-based decision-making in agritourism development. Its data-driven recommendations contribute not only to the academic discourse but also to the formulation of sustainable policies that can foster long-term rural development in Romania.

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Definition and Role of Agritourism in Sustainable Development

Agritourism extends beyond conventional tourism by integrating agricultural practices with visitor experiences, creating a sustainable economic model that supports rural development [26]. This sector fosters the promotion of local culture and natural landscapes while providing economic benefits through entrepreneurial activities and diversified income streams. Unlike mass tourism, which often imposes environmental and social pressures on host communities, agritourism follows a more balanced approach, one that seeks to preserve resources while simultaneously driving economic growth [27,28,29].

In the context of accelerating urbanization and workforce migration to industrial and service sectors, it is a known fact that agritourism presents a viable alternative for revitalizing rural economies [30,31]. Encouraging local entrepreneurship and strengthening short supply chains can help mitigate the risks associated with fluctuating agricultural markets. Furthermore, the expansion of employment opportunities in related sectors, such as hospitality, artisanal crafts, and traditional food production [32], can slow population decline and enhance overall living standards in rural areas.

Mountain regions, in particular, stand to benefit significantly from agritourism because their rich natural landscapes and well-preserved traditions offer unique advantages in attracting visitors seeking authentic rural experiences [33]. However, realizing that the full potential of agritourism requires more than just natural beauty and cultural heritage, a well-structured strategy is necessary to transform these assets into a sustainable economic driver. Without targeted investments in infrastructure, workforce training, and strategic marketing, agritourism risks remaining an underutilized opportunity rather than a key contributor to regional development, a situation in which for agritourism to thrive as a pillar of rural economies, collaboration between policymakers, investors, and local entrepreneurs is essential, and coordinated efforts can ensure that resources are allocated efficiently, maximizing long-term benefits while fostering a resilient and competitive agritourism sector.

2.2. Case Studies and Experiences from Similar Regions

Examining successful agritourism models across Europe reveals that the development of this sector is not spontaneous. Instead, it results from well-structured public policies, strategic investments, and the active involvement of private stakeholders. In numerous EU member states, agritourism has evolved into a key driver of rural economic development [34], effectively integrating tourism with agriculture, a synergy that has not only generated sustainable economic benefits but has also contributed to revitalizing rural communities, particularly in areas facing economic decline.

A compelling example is Austria, where small-scale farms in mountain regions have flourished due to targeted government subsidies and specialized training programs for agritourism operators [35]. These initiatives have enabled farmers to expand their income sources by offering tailored tourism experiences while maintaining the region’s agricultural character. As a result, previously isolated Alpine villages have been successfully transformed into internationally recognized tourist destinations, demonstrating the fact that Austria’s approach has balanced economic expansion with heritage conservation, preventing the negative externalities associated with mass tourism.

Tuscany, Italy, presents another notable case, illustrating how rural identity can be effectively harnessed to create a thriving agritourism sector [36]. Through a combination of public policy support and entrepreneurial initiatives, traditional farmhouses, vineyards, and olive groves have been repurposed into high-end rural accommodations. The “Agriturismo” [37] brand has become synonymous with quality and authenticity, thanks to a cohesive marketing strategy and the seamless integration of local products and experiences into the tourism offering, a model that highlights the significance of regional branding and identity, important for enhancing a destination’s market competitiveness.

A more regionally relevant example is Bucovina, Romania, where rural guesthouses have successfully attracted visitors by promoting local businesses, traditional architecture, and authentic cuisine. However, unlike the Austrian or Italian models, Bucovina’s agritourism development has been uneven and fragmented, largely due to the absence of a strategic, long-term vision. The result has been an overconcentration of tourist activity in a few key areas, while other communities with similar potential remain underdeveloped, a disparity that underscores the stringent need for an integrated policy approach, one that ensures balanced investment distribution and mitigates the risks of over-tourism while preserving the sustainability of local resources [38,39,40,41,42,43].

From these case studies, it can be concluded that a clear pattern emerges: the success of agritourism depends on a coordinated strategy that prioritizes infrastructure development, financial incentives, and effective regional promotion. Without a systematic approach, rural tourism risks becoming disjointed, inefficient, and economically unsustainable. Therefore, collaborative policymaking, public-private partnerships, and targeted financial mechanisms are critical to maximizing the long-term economic and social benefits of agritourism.

Decision models for evaluating tourism development priorities: justification for the TOPSIS method and the relevance of the study. Multi-criteria decision analysis is widely used in economic and strategic planning, with various methodologies available to assess and rank development alternatives and each method presents distinct advantages and limitations, influencing its applicability in different contexts. Within the field of tourism and economic resource allocation, some of the most recognized approaches include:

- -

- Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is a widely used method that relies on pairwise comparisons to determine the relative importance of criteria. While effective for structuring decision problems hierarchically, AHP becomes increasingly complex and resource-intensive when dealing with a large number of alternatives [44].

- -

- DEMATEL (Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory) is a methodology designed to identify cause-effect relationships between decision criteria. It is particularly valuable for analyzing the interdependencies of factors in complex decision-making scenarios but less suited for directly ranking alternatives [45].

- -

- ELECTRE (Elimination and Choice Expressing Reality) is a technique that filters out alternatives that fail to meet predefined essential criteria. Although effective in eliminating unsuitable options, it does not offer a structured ranking of alternatives based on their overall performance [46].

- -

- TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) is a ranking model that assesses alternatives based on their proximity to an ideal solution while also considering their distance from the least favorable option. This method provides an objective and easily interpretable classification, making it highly applicable in contexts requiring clear and actionable results [47].

Among these, the TOPSIS model was chosen for the study due to its practical advantages in economic and strategic decision-making because it was considered that this method is intuitive, does not require extensive pairwise comparisons like AHP, and directly ranks alternatives, making it a suitable tool for prioritizing tourism development strategies.

Its effectiveness has been demonstrated in various domains, ranging from human resource management [48] and investment risk assessment [49] to optimizing public sector funding allocation. In the tourism industry, TOPSIS has been applied in evaluating destination competitiveness, ranking accommodation facilities, and determining infrastructure investment priorities [50]. For instance, in Poland, it has been employed to classify cities based on their touristic appeal [51], while in China, it has facilitated the identification of high-impact investment areas for rural tourism growth [52].

The research proposes the employment of TOPSIS as a decision-making model to evaluate and rank agritourism development alternatives in a structured and data-driven manner. By incorporating quantifiable indicators and well-defined evaluation criteria, this methodology ensures objectivity and comparability in assessing various strategies. Unlike traditional qualitative analyses, which often rely on subjective assessments, TOPSIS provides a systematic and transparent framework, making it easier to identify the most effective solutions based on their economic, social, and environmental relevance.

At the same time, the study contributes to the existing body of knowledge by offering a replicable analytical approach tailored to Romania’s agritourism sector. Instead of being guided solely by broad market trends or expert opinions, the study introduces a method that quantifies key decision factors, ensuring that strategic planning is grounded in empirical evidence. The findings are designed to serve as a decision-support tool for policymakers, private investors, and local stakeholders, enabling them to allocate resources efficiently and promote sustainable rural tourism development.

Furthermore, for the northwest region of Romania, applying TOPSIS will facilitate the ranking of agritourism development options based on measurable performance indicators, providing an analytical foundation for informed and strategic decision-making. By reducing the risk of inefficient investments and subjective biases, this approach has the potential to provide a more balanced, long-term, and sustainable expansion of rural tourism in the region.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area: The North-West Region of Romania and Its Agritourism Potential

The North-West region of Romania, which includes the counties of Maramureș, Bihor, Bistrița-Năsăud, Cluj, and Sălaj, presents significant potential for agritourism development [53], potential that stems from a combination of picturesque mountain landscapes, well-preserved cultural traditions, and a rural economy still largely dependent on agriculture. Despite these advantages, the region also faces structural barriers, such as insufficient infrastructure, accessibility limitations in certain areas, and a lack of comprehensive tourism integration within the regional economic strategy.

Maramureș stands out as a key destination for rural tourism, largely due to its traditional wooden architecture, craftsmanship, and distinctive cultural heritage [54]. However, tourism development is concentrated around a few high-profile attractions, including the Mocănița steam train on the Vaser Valley and the Merry Cemetery (Cimitirul Vesel) in Săpânța. As a result, other areas with significant agritourism potential remain underexploited, leading to resource pressures in overcrowded areas while limiting the economic benefits for the broader region.

Bihor boasts a diverse tourism landscape, with renowned spa resorts (e.g., Băile Felix, Băile 1 Mai) and extensive mountain trails in the Apuseni Mountains [55]. However, agritourism remains underdeveloped, largely due to the lack of integration between tourism services and the local economy. While wellness and adventure tourism have flourished, rural tourism has not received the same level of strategic support, leaving many communities without direct economic benefits from tourism-related activities.

Cluj and Bistrița-Năsăud benefit from better-developed infrastructure and their proximity to major urban centers, which facilitates steady tourist flows. However, despite these logistical advantages, agritourism remains in an early stage, with few structured initiatives leveraging the region’s natural landscapes, culinary heritage, and traditional crafts [56].

Finally, Sălaj, though characterized by a strong cultural identity, has struggled to position itself as a notable agritourism destination of the analyzed region. The limited promotion of its rural assets, linked with insufficient investment in infrastructure, has restricted its ability to attract visitors and integrate tourism into its economic framework [57].

These disparities in agritourism development across counties emphasize the need for a comparative assessment based on objective criteria, which is why identifying priority areas for investment and implementing a regionally coordinated strategy could maximize local resource utilization while enhancing the region’s competitiveness within both Romania and the broader Central European market.

Given these dynamics, a multi-criteria decision analysis model such as TOPSIS offers a valuable tool for ranking strategic development alternatives and optimizing decision-making in agritourism. The North-West region of Romania is uniquely positioned to expand its agritourism sector, yet its development remains fragmented, influenced by factors such as infrastructure quality, accessibility, marketing efforts, and local economic integration.

To provide a clearer perspective on each county’s agritourism potential and challenges, the following table outlines their strengths and weaknesses, offering a comparative framework for identifying development opportunities in the region (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of agritourism potential in the counties of Romania’s North-West Region.

The comparative assessment of the counties in Romania’s North-West region highlights significant variations in agritourism development. While each county benefits from distinct natural and cultural resources, disparities in infrastructure quality, promotional efforts, and integration within the local economy influence both the attractiveness and long-term viability of this sector. We consider that addressing these imbalances requires a well-structured development strategy that prioritizes targeted investments, infrastructure modernization, and enhanced visibility of agritourism offerings. By adopting a more cohesive and regionally coordinated approach, stakeholders can maximize the economic potential of agritourism while ensuring its sustainability and competitiveness in the broader tourism market.

3.2. Selection of the Alternatives and the Criteria of the Decision Analysis

Identifying the most effective agritourism development strategies for Romania’s North-West region required a structured and methodologically rigorous approach. The selection of alternatives and evaluation criteria was based on a comprehensive multi-step process that integrated documentary research, expert consultations, and an in-depth analysis of tourism market trends. These methodological components ensured that the decision-making framework was data-driven, aligned with industry realities, and reflective of regional specificities.

To achieve a balanced and well-substantiated selection of alternatives, several critical factors were considered:

- Existing research on rural tourism in Romania and Europe, including comparative studies on agritourism models implemented in countries with similar geographic and economic conditions. The literature provided valuable insights into best practices and common challenges in agritourism development [58,59].

- Assessment of tourist preferences and demand patterns, collected from regional tourism reports and statistical data, to identify trends in visitor expectations and behavioral shifts. This analysis helped pinpoint high-demand agritourism experiences most relevant to the region [60,61].

- Direct consultations with local stakeholders, including public authorities, tourism entrepreneurs, local producers, and rural community representatives. These interviews and focus groups provided first-hand perspectives on economic feasibility, market opportunities, and challenges related to agritourism development [62,63,64].

- Economic feasibility and long-term sustainability considerations, ensuring that the selected alternatives are financially viable, environmentally responsible, and capable of generating stable income streams for local communities [65,66].

Following these guiding principles, five core agritourism development alternatives were selected, each representing a strategic investment pathway tailored to maximize the region’s tourism potential and ensure economic sustainability:

A1: Development of rural guesthouses—Investing in rural accommodations remains a fundamental pillar of agritourism growth. The rising demand for authentic lodging experiences makes this alternative highly attractive, as it generates direct income for rural households and creates employment opportunities within local communities. Drawing from successful European models, where rural accommodations serve as anchors for sustainable tourism, this strategy strengthens the economic resilience of rural areas while preserving cultural authenticity [67,68].

A2: Promotion of local products in tourism—Integrating regional agro-food products, such as artisan cheeses, honey, and handcrafted goods, into the tourism experience is a proven method for boosting rural economies. This alternative diversifies income sources for local producers while enhancing the visitor experience through cultural and gastronomic immersion. As consumer preferences increasingly shift toward authentic, locally sourced products, this approach creates a distinct competitive advantage for the region [69,70,71].

A3: Implementation of ecotourism routes—Developing thematic hiking, cycling, and nature exploration trails aligns with the growing demand for sustainable and active tourism. This approach leverages the region’s natural beauty and biodiversity, supporting tourism growth while reducing visitor concentration in overdeveloped areas. Ecotourism not only enhances environmental sustainability but also stimulates local economies through eco-friendly tourism services [72,73,74].

A4: Development of integrated tourism packages—Offering bundled tourism experiences that combine accommodation, traditional gastronomy, and local activities enhances economic viability by encouraging longer visitor stays. This model has been successfully implemented in mature tourism markets and is particularly effective in generating steady income flows and boosting regional competitiveness [75,76,77].

A5: Creation of tourist information centers—One of the main obstacles to rural tourism expansion is the lack of accessible and structured visitor information. Establishing regional information centers can improve tourism coordination and marketing, helping visitors discover lesser-known agritourism attractions. These centers strengthen visitor engagement and serve as a bridge between tourists and local businesses [78,79,80,81].

Each of these development alternatives presents a strategic pathway for maximizing agritourism’s economic impact in Romania’s North-West region, ensuring that investments align with long-term sustainability goals.

3.2.1. Representation of Respondents Across Counties

To further substantiate the selection of agritourism development alternatives, the study included data from respondents across the five counties that comprise the North-West region of Romania. The distribution was as follows: Bihor—28.43% of respondents; Bistrița-Năsăud—25.49% of respondents; Maramureș—24.51% of respondents; Sălaj—15.69% of respondents; Cluj—5.88% of respondents. The high representation of Bihor, Bistrița-Năsăud, and Maramureș in the survey aligns with these counties’ strong agritourism traditions and active tourism sectors. In contrast, Sălaj and Cluj had lower response rates, which may reflect underdeveloped agritourism infrastructure or lower industry engagement. However, their inclusion ensures that the analysis remains regionally comprehensive, capturing a broad spectrum of agritourism development levels.

3.2.2. Evaluation Criteria for Agritourism Initiatives

The assessment of agritourism development alternatives required a structured evaluation process, considering key factors that influence investment feasibility and long-term success. As a result, the following dimensions were used as essential evaluation criteria:

C1: Infrastructure accessibility—the degree to which a region is easily reachable plays a critical role in attracting visitors and facilitating business growth. Developed road networks, public transportation access, and essential utilities are fundamental for enhancing agritourism investments, as limited connectivity hinders tourism expansion [82,83,84].

C2: Diversity of tourism offers—a varied tourism portfolio increases a destination’s attractiveness by catering to different traveler preferences. A balanced mix of nature-based activities, cultural experiences, and gastronomic tourism enhances a region’s market positioning and mitigates seasonality challenges [85,86,87].

C3: Quality of tourism services—a positive visitor experience depends on high service standards across accommodation, hospitality, and local products. Investing in service excellence fosters tourist satisfaction, repeat visits, and long-term economic stability [88,89,90].

C4: Economic sustainability—ensuring that agritourism remains profitable is crucial for both investors and rural communities. A self-sustaining tourism sector generates stable benefits by stimulating local economies, creating jobs, and attracting further investment [91,92,93,94].

By applying these evaluation criteria in conjunction with the TOPSIS method, a data-driven framework is established for prioritizing agritourism investments. The structured, quantitative approach minimizes subjectivity, enhances strategic planning, and reduces the risk of inefficient resource allocation. Ultimately, the findings support the formulation of a sustainable agritourism development strategy for Romania’s North-West region, ensuring long-term competitiveness and economic resilience.

3.3. Research Design

3.3.1. Demographic Analysis of Respondents

Ensuring a comprehensive and representative dataset, the study utilized a sample of 102 respondents, carefully selected to reflect the diverse range of stakeholders actively engaged in agritourism development. The selection process followed predefined criteria, prioritizing professional experience and level of involvement in rural tourism to ensure a balanced and multi-perspective analysis of both opportunities and constraints within the sector.

The composition of respondents was structured to include key actors shaping the agritourism landscape. Rural guesthouse owners (40%) were surveyed to provide insights on profitability, market demand, and operational challenges. Farmers and local producers (25%) contributed perspectives on integrating local products into tourism services and enhancing rural value chains. Visitors and tourists (20%) were included to capture consumer preferences and key factors influencing travel decisions. Meanwhile, local government representatives (15%) provided viewpoints on policy frameworks, public investments, and tourism-supportive infrastructure development.

A geographical balance across the North-West region of Romania was ensured by distributing responses proportionally across Bihor (28.43%), Bistrița-Năsăud (25.49%), Maramureș (24.51%), Sălaj (15.69%), and Cluj (5.88%). This allocation reflects the varied levels of agritourism development across the counties, ensuring the study captured insights from both established and emerging agritourism destinations. While counties like Bihor and Maramureș have a strong tradition in rural tourism, Cluj and Sălaj are at different stages of sectoral expansion, allowing for a comparative analysis of regional disparities and potential growth trajectories.

To ensure efficient data collection and minimize external biases, the survey was administered online using a structured digital questionnaire. This method facilitated broad accessibility and allowed respondents to complete the survey at their convenience while reducing potential interviewer influence. The survey was distributed through professional agritourism networks, local business associations, and tourism development organizations, ensuring that targeted respondents actively involved in agritourism participated. Additionally, personalized email invitations were sent to selected stakeholders, supplemented by weekly reminder notifications to enhance response rates. The survey remained open for four weeks, ensuring that participants had adequate time to provide well-informed responses.

3.3.2. Questionnaire Development and Validation

A well-structured and methodologically robust questionnaire was designed to ensure clarity, conciseness, and ease of completion, while simultaneously capturing in-depth insights from stakeholders. To prevent ambiguities and respondent fatigue, particular attention was given to formulating and sequencing questions, ensuring that the survey maximized engagement and data accuracy. The data collection took place in 2024, ensuring that the insights gathered accurately reflect the current state of agritourism in Romania’s North-West region.

The questionnaire was divided into three core sections, each targeting a specific dimension of agritourism development. The first section focused on demographic information, collecting key respondent characteristics such as gender, age, county of residence, occupation, and tourism-related experience. This segmentation allowed for a deeper interpretation of stakeholder perspectives based on socio-professional backgrounds.

The second section involved the assessment of agritourism development alternatives, requiring participants to evaluate five proposed strategies: rural guesthouses, local product promotion, ecotourism routes, integrated tourism packages, and tourist information centers. Each alternative was rated on a scale from 1 to 10, with four decision-making criteria forming the basis of evaluation: infrastructure accessibility, diversity of tourism offers, service quality, and economic sustainability. This structured rating system allowed for objective comparisons and provided empirical backing for alternative prioritization.

The third section focused on weighting the importance of decision criteria, where respondents ranked the four key factors based on their perceived influence in investment and policy formulation for agritourism development. Using an ordinal scale, this step ensured that the final rankings accounted for stakeholder priorities and sector-specific realities.

To enhance the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, a pilot study was conducted before full-scale distribution. A small yet diverse group of stakeholders, including representatives from each respondent category, participated in this preliminary phase. The pilot study helped identify inconsistencies, assess question clarity, and refine survey wording to eliminate misinterpretations. Based on the feedback received, minor structural and wording adjustments were made to optimize data collection and ensure that the final instrument was well-calibrated for empirical analysis.

By employing a structured, multi-phase approach to questionnaire design and administration, the study minimized response bias, strengthened data accuracy, and ensured a holistic representation of agritourism stakeholders across the North-West region. The methodology also reinforced alignment between survey findings and real-world agritourism challenges, providing a robust foundation for strategic decision-making in rural tourism development.

3.4. The TOPSIS Model: Foundations, Application Procedures, and Statistical Tools Applied

This approach allowed us to objectively rank alternatives by assessing their proximity to an ideal solution while measuring their divergence from the least favorable option. One key advantage of TOPSIS is its ability to introduce transparency and reduce subjectivity, which is relevant in investment and policy decisions within agritourism. To ensure a data-driven evaluation, a structured questionnaire survey and the responses using statistical techniques. By calculating arithmetic means for each alternative, we established a solid quantitative basis for ranking. The implementation followed a standardized six-step methodology, ensuring both reliability and consistency in the findings.

Using a structured model like TOPSIS is essential in agritourism, where decisions must balance economic, environmental, and social considerations. Without such an objective framework, investment choices risk being influenced by short-term market trends rather than long-term sustainability.

The present study highlights the importance of data-driven decision-making in fostering sustainable agritourism development. The application of TOPSIS followed a standardized six-step methodology, ensuring the consistency and reliability of the results:

- Decision matrix construction: raw data from the questionnaire were structured into a decision matrix, where each row corresponded to an agritourism development alternative, and each column represented an evaluation criterion. This organization of data ensured that all key variables were systematically included for comparative analysis.

- Normalization of data: given that the selected evaluation criteria used different measurement scales (e.g., rating scores, economic impact values), the dataset was normalized to establish comparability across all factors to eliminate potential distortions in the ranking process.

- Assignment of weightings to criteria: to reflect the relative importance of each evaluation criterion, weight values were assigned based on survey responses. By incorporating stakeholder priorities, this step ensured that the ranking aligned with real-world market dynamics and policy considerations.

- Identification of ideal and anti-ideal solutions: the best-performing values for each criterion (ideal solution) and the least favorable values (anti-ideal solution) were determined, an important step in establishing benchmarks, allowing for a more precise comparison of each alternative.

- Calculation of distances to benchmark solutions: using a Euclidean distance formula, the proximity of each alternative to the ideal solution and its divergence from the anti-ideal solution was computed, and the closer an alternative was to the ideal reference point and the farther it was from the least desirable option, the higher its relative performance score.

- Computation of the TOPSIS Performance Coefficient (Ci): based on the calculated distances, a performance index (Ci) was assigned to each alternative. This final step allowed for the ranking of agritourism development strategies based on their quantitative viability. Alternatives with higher Ci scores were deemed more suitable for investment and policy implementation, while those with lower scores indicated areas requiring further development or strategic adjustments.

By adopting this methodologically rigorous approach, we can affirm that the study offers a structured decision-making framework for agritourism development as long as the use of TOPSIS enables evidence-based prioritization, facilitating more effective resource allocation, strategic investment planning, and sustainable policy implementation.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Collected Data

A thorough demographic analysis of respondents is mandatory for capturing stakeholder perspectives on agritourism development in Romania’s North-West region. By examining factors such as county of origin, professional background, tourism experience, gender, and age, significant trends that influence rural tourism can be identified. These insights provide a foundation for designing targeted policies that align with regional needs and support sustainable agritourism growth.

The data reveal a high concentration of respondents in Bihor (28.43%), Bistrița-Năsăud (25.49%), and Maramureș (24.51%), highlighting strong regional engagement in agritourism. In contrast, Sălaj (15.69%) and Cluj (5.88%) had lower participation, potentially reflecting slower rural tourism growth. These disparities indicate the need for region-specific development efforts. Regarding their professional roles, farmers (21.57%) and local government representatives (19.61%) emerged as the most engaged, emphasizing the role of agriculture and public policy in agritourism. Meanwhile, guesthouse owners (17.65%) and tourists (17.65%) provide insights into market demand and business operations, while diverse stakeholders (23.53%) contribute additional perspectives. The strong presence of farmers reinforces the link between local production and tourism, while government involvement signals institutional interest in the sector. Tourism experience levels vary, with 60.78% having prior experience in mountain tourism and 39.22% being new to the field. This suggests both a knowledgeable respondent base and a growing interest in agritourism investments. Gender distribution is relatively balanced (52.94% male, 47.06% female), reflecting equal access to agritourism opportunities despite male dominance in farming and governance roles, while the age analysis shows strong engagement from younger generations, with 31.37% aged 25–34 and 21.57% under 25, highlighting rural tourism’s appeal to younger travelers and entrepreneurs. Meanwhile, older respondents (35–55+) remain active, presenting opportunities for investment and experience-driven contributions. To enhance comparability, the obtained data were structured into a table, facilitating regional analysis, stakeholder insights, and demographic trends, providing a data-driven foundation for agritourism strategy development (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic analysis of respondents.

The demographic profile of respondents provides valuable insights into the stakeholders shaping rural tourism development in Romania’s North-West region. The high engagement from counties with strong mountain tourism traditions suggests regional interest in sector growth, while the notable presence of farmers and local government representatives highlights the importance of public-private collaboration. With most respondents having experience in mountain tourism, the data reflect credible industry perspectives and active involvement in its advancement. The balanced gender distribution and strong participation of younger individuals indicate growth potential, emphasizing the need for innovative promotion and policies supporting rural entrepreneurship. At the same time, the findings serve as a foundation for strategic decision-making, guiding efforts to attract investment, optimize local resources, and enhance agritourism’s economic sustainability.

4.2. Application of the TOPSIS Model: Intermediate and Final Results

In this section, the TOPSIS method was employed to evaluate and rank the given alternatives based on specific criteria. The analysis followed a structured process, beginning with the normalization of the decision matrix to ensure comparability across varying units of measurement. Next, the weighted normalized matrix was computed, integrating the significance of each criterion into the evaluation. Following this, both the ideal and negative-ideal solutions were determined, serving as reference points for assessing the relative performance of each alternative. The calculation of distances from these benchmarks allowed for a precise measurement of how closely each alternative aligned with the optimal scenario. Finally, the relative closeness coefficient was computed, establishing a clear ranking of the alternatives in order of preference. The following subsections provide a detailed breakdown of each step, outlining the rationale behind these methodological choices and the key insights derived from the results. The application of the TOPSIS method began with the normalization of the decision matrix, a necessary step to standardize all criteria on a common scale. Given that the criteria varied in units and range, direct comparisons would have introduced bias into the analysis. Normalization eliminated these inconsistencies, ensuring a fair and objective evaluation of alternatives. In this study, four criteria and five alternatives were assessed using the TOPSIS methodology. The decision matrix, constructed based on the survey results, is presented in the following table, forming the foundation for the subsequent calculations (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Normalization of the decision matrix.

The normalization formula applied in this study transformed the raw data into a standardized format, ensuring that all criteria were evaluated on a common scale. This step was essential for maintaining fairness in the comparison process, as it prevented any single criterion from disproportionately influencing the results due to differences in measurement units or magnitude. By normalizing the data, a clearer representation of how each alternative performed relative to the others across all criteria was achieved (see Table 4).

Table 4.

The normalized matrix.

To achieve this, we used the following normalization formula:

4.2.1. Weighted Normalized Decision Matrix

After normalizing the decision matrix, weighting was employed in order to reflect the relative importance of each criterion in the evaluation process. Since all criteria in this study were considered equally significant, each was assigned a weight of 0.25. To incorporate these weights, each value in the normalized matrix by the corresponding criterion weight. This step ensured that the ranking process accounted not only for the relative performance of alternatives but also for the predefined importance of each criterion. The weighted normalized decision matrix was calculated using the following formula:

After completing the normalization process, the next step was to apply weights to the normalized decision matrix. These weights represented the relative importance of each criterion in the decision-making process, ensuring that the final rankings accurately reflected their significance. In this study, all criteria were assigned equal importance, with a weight of 0.25 each.

By multiplying the normalized values by their respective weights, the weighted normalized decision matrix was obtained. This transformation allowed us to integrate both the raw performance of each alternative and the assigned importance of the criteria, and the weighted matrix served as the foundation for the next steps, where it was identified the ideal and negative-ideal solutions and calculated the distances of each alternative from these benchmarks (see Table 5).

Table 5.

The weighted normalized matrix.

4.2.2. Determination of Positive and Negative Ideal Solutions

In this step, the positive ideal solution (PIS) and negative ideal solution (NIS) were used to measure how close each alternative was to the best and worst possible outcomes. The PIS represents the most favorable values for each criterion, while the NIS reflects the least desirable ones. These benchmarks were determined using the following formulas:

So that

where j1 and j2 denote the negative and positive criteria, respectively.

The TOPSIS method evaluates alternatives by comparing them to ideal benchmarks. The positive ideal solution (PIS) represents the best possible performance across all criteria, while the negative ideal solution (NIS) reflects the worst. These are identified by selecting the maximum and minimum values for each criterion in the weighted normalized matrix. Serving as reference points, these solutions help measure how close each alternative is to the optimal or least favorable outcome (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Positive and negative ideal solutions.

4.2.3. Distance from Positive and Negative Ideal Solutions

After determining the ideal solutions, further work was made on the Euclidean distance of each alternative from both the positive ideal solution (PIS) and the negative ideal solution (NIS). The distance to the PIS reflects how close an alternative is to the best possible performance, while the distance to the NIS indicates how far it is from the worst-case scenario. These distances were computed using the following formulas:

These distances play a key role in determining the relative closeness degree, which ultimately ranks the alternatives. A shorter distance to the positive ideal solution (PIS) and a greater distance from the negative ideal solution (NIS) indicate a stronger overall performance. This relative closeness measure serves as the basis for the final ranking of alternatives (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Distance to positive and negative ideal points.

4.2.4. Relative Closeness Degree and Ranking of Alternatives

The final step in the TOPSIS method was calculating the relative closeness degree (Ci) for each alternative. This value measured how close an alternative was to the positive ideal solution (PIS) relative to its distance from the negative ideal solution (NIS). A higher Ci indicated stronger performance, with 1 being the optimal score. Based on these values, the alternatives were ranked accordingly.

Based on the Ci values, the alternatives were ranked, offering a clear and objective prioritization of options for agrotourism development. This ranking helped identify the most favorable choices, ensuring that decisions were guided by a systematic and data-driven approach (see Table 8).

Table 8.

The ci value and ranking.

4.3. Identification and Prioritization of Agrotourism Development Priorities

In this section of the study, we analyzed the findings of the TOPSIS evaluation to identify and prioritize the most feasible strategies for agritourism development. By ranking the available alternatives, critical insights into which options best meet essential criteria, such as accessibility to infrastructure, the variety of tourism experiences, service quality, and long-term economic sustainability. Understanding these rankings allows us to assess which alternatives hold the greatest potential for fostering sustainable growth in rural tourism. At the same time, to provide a deeper perspective, we focus on the highest-ranked alternatives, examining their key advantages and potential challenges. This approach enables us to evaluate their broader impact on the agritourism sector and determine how they can contribute to regional development, while the findings offer valuable guidance for policymakers and stakeholders looking to implement well-informed, data-driven strategies that support both local economies and sustainable tourism practices.

4.3.1. Ranking of Alternatives Based on TOPSIS Results

By applying the TOPSIS method, we were able to evaluate and rank the alternatives based on their relative closeness degree (Ci) to identify the most effective strategies for agritourism development. This ranking offers critical insights into which initiatives best align with key evaluation criteria and demonstrate the highest potential for success. The top-ranked alternative emerges as the most viable option, whereas lower-ranked ones may need further adjustments, strategic refinement, or additional support to maximize their effectiveness and long-term impact.

Alternative 3: Implementation of ecotourism routes (Ci = 0.678)—this alternative emerged as the most promising option, highlighting the growing demand for sustainable and nature-based tourism experiences.

Alternative 2: Promotion of local products in tourism (Ci = 0.602)—the second most important alternative is a strong contender, emphasizing the importance of integrating local heritage into the visitor experience.

Alternative 1: Development of rural guesthouses (Ci = 0.467)—this alternative represents a valuable option that supports community-based tourism but may require improvements in infrastructure and service quality.

Alternative 4: Development of integrated tourism packages (Ci = 0.326)—it is a strategic approach that could enhance visitor engagement but needs further refinement to increase its viability.

Alternative 5: Creation of tourist information centers (Ci = 0.316)—while useful, this alternative ranked lower, suggesting that standalone information centers may be less impactful without complementary initiatives.

4.3.2. Analysis of the Top-Ranked Alternatives

Following the analysis, we examined the strengths of the alternatives across key criteria: infrastructure accessibility, diversity of tourism offerings, quality of services, and economic sustainability, gaining valuable insights into their potential for agrotourism development and their impact on the local economy. The highest-ranked alternative, the implementation of ecotourism routes (Alternative 3), proved to be the most promising option, having the shortest distance from the positive ideal solution and the greatest distance from the negative ideal solution, indicating a strong alignment with the best conditions for agrotourism growth. This suggested that ecotourism routes had significant potential to attract nature-conscious travelers, promote sustainable tourism, and preserve the local environment, while also enhancing visitor experiences. Ranked second, the promotion of local products in tourism (Alternative 2) stood out due to its strong performance in economic sustainability and tourism service quality. By integrating locally made products into the tourism experience, this alternative supported regional businesses and traditional crafts, making the visitor experience more authentic and immersive. The results indicated that this approach helped strengthen the connection between tourism and local communities, creating opportunities for sustainable growth. The development of rural guesthouses (Alternative 1) ranked third, showing moderate potential, particularly in terms of infrastructure accessibility and variety of tourism services. Rural guesthouses played a mandatory role in accommodating visitors and offering authentic, community-based experiences, but the analysis suggested that their impact could be improved through better facilities and stronger integration within the broader tourism network (See Figure 1). These findings provided a clear understanding of the most effective strategies for agrotourism development. By focusing on these key areas, we identified pathways to build a sustainable and economically viable agrotourism sector, ensuring long-term benefits for both visitors and local communities.

Figure 1.

Top-ranked alternatives. Source: authors’ elaboration, not derived or adapted from any other source.

5. Discussion

5.1. Practical Implications for Agritourism Development in Romania’s North-West Region

The TOPSIS analysis identified ecotourism route implementation (Alternative 3) as the most effective strategy for advancing sustainable agritourism in Romania’s North-West region, with a relative proximity coefficient of 0.678. This alternative aligns strongly with key sustainability criteria, including infrastructure accessibility, tourism offer diversity, service quality, and economic viability. Well-planned ecotourism trails not only stimulate adventure tourism but also minimize environmental degradation, ensuring that increased visitor traffic does not compromise the long-term ecological balance of rural landscapes. Compared to unsustainable agritourism practices—such as uncontrolled expansion of tourism facilities in ecologically sensitive areas—responsible ecotourism development fosters low-impact, nature-based tourism, supports local conservation efforts, and provides rural communities with long-term economic incentives to preserve their natural surroundings. The promotion of local products in tourism (Alternative 2, Ci = 0.602) emerged as another high-impact approach, reinforcing the integration of rural economies into sustainable tourism development. Establishing local markets, gastronomic experiences, and cultural events around traditional products not only enhances destination attractiveness but also supports small producers and artisans, fostering economic resilience in rural communities. Unlike mass tourism models that rely on imported goods and standardized services, sustainable agritourism strengthens regional identity, promotes seasonal and organic farming, and reduces the environmental footprint associated with large-scale tourism operations. The development of rural guesthouses (Alternative 1, Ci = 0.467) holds moderate potential for expanding accommodation capacity in underutilized rural areas. However, sustainability challenges arise when guesthouse expansion lacks proper regulatory oversight, leading to overdevelopment and loss of authenticity. To ensure that community-run lodging establishments contribute to sustainable rural tourism, investments should focus on infrastructure improvements such as transport connectivity, waste management solutions, and responsible visitor management systems.

Conversely, integrated tourism packages (Alternative 4, Ci = 0.326) and the creation of tourist information centers (Alternative 5, Ci = 0.316) ranked lower. While these initiatives enhance visitor experiences, they are not primary drivers of sustainable agritourism growth. Findings suggest that before prioritizing secondary measures, it is essential to first strengthen core tourism infrastructure and ensure the inclusion of local businesses in sustainable tourism value chains.

Incorporating these results into policy planning and investment strategies can facilitate the long-term viability of agritourism. Unlike unsustainable models, which prioritize short-term economic gains over environmental and cultural preservation, this study underscores the need for strategically structured investments, public-private partnerships, and comprehensive marketing strategies that align economic benefits with sustainability principles.

5.2. Strategic Recommendations Based on the TOPSIS Results

The findings emphasize the need for a cohesive and sustainability-focused agritourism strategy, integrating environmental conservation, economic resilience, and community engagement.

For policymakers, priority should be given to infrastructure projects that enhance accessibility to rural destinations while preserving the region’s environmental integrity. This means prioritizing low-impact transportation networks, waste management systems, and zoning regulations that prevent overdevelopment. A well-balanced tourism regulatory framework should also be established to ensure visitor flows are managed sustainably, preventing the negative consequences of overtourism in sensitive ecological areas. For investors, the results highlight opportunities in ecotourism and gastronomic tourism, particularly in eco-friendly accommodations, sustainable outdoor activity centers, and local product branding. Unlike mass-market investments that often lead to resource depletion, sustainable tourism infrastructure—such as off-grid lodges, farm-to-table restaurants, and agri-experience hubs—can generate long-term returns while aligning with global sustainability trends. Partnerships between investors and local producers can enhance regional supply chains, ensuring that tourism revenues directly benefit rural communities rather than being absorbed by external stakeholders. For local communities, sustainable agritourism presents an opportunity to diversify income streams while preserving cultural traditions and natural heritage. Small-scale producers and rural entrepreneurs can capitalize on regional branding, integrating traditional markets, farm visits, and experiential tourism into a cohesive agritourism offering. Closer collaboration between farmers and tourism operators can create innovative agritourism experiences, maximizing economic impact without compromising environmental sustainability.

Based on the findings and recommendations, a multi-stakeholder approach—involving policymakers, investors, and local communities—is essential to establishing a sustainable agritourism model that balances economic growth with responsible resource management. Unlike conventional tourism approaches, which often prioritize short-term profit over long-term viability, sustainable agritourism ensures that rural development is both economically viable and environmentally responsible, securing long-term benefits for all involved stakeholders.

5.3. Theoretical Implications and Alignment with International Research

The findings of the study contribute to the broader academic discourse on sustainable agritourism development, aligning with international research that underscores the necessity of balancing economic growth with environmental and cultural preservation. Existing studies in European contexts, such as Austria and Italy, mentioned in the introduction of the paper, highlight the transformative role of agritourism in revitalizing rural economies through policy-driven investments in ecotourism and local production integration. Similar to these models, the results of this research reinforce that ecotourism routes and local product promotion represent the most viable development pathways in Romania’s North-West region. By emphasizing nature-based tourism and strengthening rural supply chains, these approaches align with established best practices observed in sustainable tourism models across Europe.

Furthermore, international studies on agritourism in North America and Australia suggest that guesthouse development can significantly contribute to rural economic sustainability, provided that regulatory frameworks prevent overdevelopment and environmental degradation [95,96,97,98,99]. This study confirms the findings by demonstrating that, while rural guesthouses have moderate potential for tourism expansion in Romania, their long-term success hinges on infrastructure investments and sustainable visitor management policies. Without these structural interventions, unchecked expansion could lead to loss of authenticity and increased strain on local resources, mirroring the challenges documented in other tourism-dependent rural regions. The findings also relate to research from emerging agritourism markets, such as China, where government-supported tourism information centers and integrated tourism packages have been positioned as key facilitators of sectoral growth [98]. However, in contrast to these contexts, this study found that in Romania’s North-West region, these initiatives have lower immediate impact, suggesting that a more fundamental investment in core agritourism infrastructure is necessary before such secondary measures can drive meaningful growth. This distinction highlights the importance of adapting international strategies to local economic conditions and development stages.

By situating these results within the global body of agritourism literature, this research strengthens the theoretical understanding of sustainable agritourism as a multi-dimensional process, dependent on strategic prioritization of investment, policy support, and responsible tourism planning. The findings reinforce the applicability of multi-criteria decision-making tools such as TOPSIS, which was successfully used in this research, in structuring tourism development strategies, further supporting international research advocating for data-driven, sustainability-focused approaches in rural tourism planning.

6. Conclusions

The study applied the TOPSIS methodology to assess and rank agritourism development strategies in Romania’s North-West region, providing a structured, data-driven prioritization of alternatives. Findings indicate that the implementation of ecotourism routes represents the most viable and impactful strategy (Ci = 0.678), highlighting the region’s natural resources and existing infrastructure as strong enablers of sustainable tourism expansion. Beyond environmental conservation, this approach has the potential to stimulate local economic growth, increase sustainable tourist inflows, and enhance rural community resilience. The second-ranked alternative, promoting local products in tourism (Ci = 0.602), reinforces the importance of integrating local economies into the tourism sector. The findings suggest that emphasizing regional products, including traditional foods and handicrafts, not only supports local producers but also strengthens cultural identity, positioning tourism as a driver of community-based economic development. Strengthening the connection between tourism and small businesses creates opportunities for sustainable economic diversification and enhances market access for rural producers. The development of rural guesthouses (Ci = 0.467) demonstrates moderate potential for expanding accommodation capacity, though its success depends on strategic infrastructure investments, particularly in road access and complementary tourism services. Without these enhancements, expanding accommodation alone may not significantly improve visitor attraction. Lower-ranked alternatives, such as integrated tourism packages (Ci = 0.326) and tourist information centers (Ci = 0.316), appear to have a lower impact in the early stages of agritourism development. The results suggest that these initiatives become more effective once essential tourism infrastructure is well-established and local businesses are fully integrated into the sector.

Overall, the findings indicate that priority should be given to ecotourism route development, closely followed by promoting local products within tourism, as these strategies exhibit the highest potential for fostering sustainable agritourism and stimulating rural economic growth. However, long-term success will depend on continuous investments in infrastructure, policy support, and active community involvement, ensuring a holistic and sustainable approach to agritourism development in the region.

6.1. Contribution to Sustainable Development and Agritourism

This research contributes to sustainable development by applying a quantifiable decision-making model, offering replicable and adaptable insights for policymakers, researchers, and tourism planners. The results reinforce the strategic role of ecotourism in preserving biodiversity, reducing environmental impact, and ensuring equitable economic benefits within rural communities. The findings further emphasize the importance of balancing natural resource conservation with economic development, ensuring that tourism revenues are distributed fairly across rural areas rather than being concentrated in isolated locations.

By integrating local agriculture, diversifying tourism offerings, and implementing long-term infrastructure improvements, Romania has the opportunity to strengthen its position in the rural tourism sector. The structured framework developed in this study provides valuable insights for decision-makers, supporting the formulation of evidence-based policies, investment strategies, and further research on sustainable rural tourism development.

6.2. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

While the TOPSIS method provided a structured and objective ranking of sustainable agritourism development alternatives, several limitations must be acknowledged to enhance future research accuracy. One notable constraint is the equal weighting of evaluation criteria (0.25 for each factor), which may not fully reflect their relative importance in sustainable decision-making. For instance, economic sustainability might have greater significance in regions facing economic hardship, while environmental factors might be more critical in areas with high biodiversity sensitivity. Future studies could address this issue by applying dynamic weighting techniques, such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), to refine priority rankings based on regional sustainability needs. Another limitation stems from the sample size, which, while relevant to the North-West region, may not capture wider sustainability dynamics across Romania. Expanding research to additional rural and mountainous regions could enable a comparative assessment, offering deeper insights into regional variations in agritourism sustainability. Additionally, seasonality and evolving tourism trends were not explicitly analyzed. Given that agritourism demand fluctuates across seasons, future research could integrate predictive modeling techniques to evaluate long-term sustainability and off-season tourism potential. The comparison of the TOPSIS method with alternative multi-criteria decision-making frameworks such as ELECTRE or PROMETHEE would also strengthen the methodological robustness of sustainable agritourism decision-making. Furthermore, qualitative insights—such as tourist preferences, environmental impact assessments, and perceptions of local entrepreneurs—should be incorporated to complement quantitative rankings, ensuring that sustainability recommendations reflect both empirical data and community-driven perspectives.

Although the study establishes a solid analytical foundation for sustainable agritourism development, refining methodological precision, expanding geographic scope, and integrating qualitative dimensions will enhance its practical applicability for policymakers and investors, ensuring that future agritourism initiatives are scientifically grounded and sustainability-oriented.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study and the writing of this article R.V.B. and R.C. conceived the general idea. T.I. and C.M.M. was responsible for the design of the research. M.A.D., A.I.C., A.E.M.G., V.G.H., A.U. and D.P.B. collected and analyzed the data and synthetized the information and, drew the main conclusions, and developed the proposals. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Oradea, Str. Barbu Ştefănescu Delavrancea nr. 4, Oradea, 410087, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available based upon request from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funding institute had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ammirato, S.; Felicetti, A.M.; Raso, C.; Pansera, B.A.; Violi, A. Agritourism and sustainability: What we can learn from a systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacter, R.V.; Gherdan, A.E.M.; Dodu, M.A.; Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Pîrvulescu, L.; Brata, A.M.; Ungureanu, A.; Bolohan, R.M.; Chebeleu, I.C. The Influence of Legislative and Economic Conditions on Romanian Agritourism: SWOT Study of Northwestern and Northeastern Regions and Sustainable Development Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucki, E.W.; Roque, O.; Schuler, M.; Perlik, M. National Report for the Study on “Analysis of Mountain Areas in the European Union and in the Applicant Countries”. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/ManfredPerlik/publication/261365205 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Cattivelli, V. Climate Adaptation Strategies and Associated Governance Structures in Mountain Areas. The Case of the Alpine Regions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăgoi, M.C.; Iamandi, I.E.; Munteanu, S.M.; Ciobanu, R.; Țarțavulea, R.I.; Lădaru, R.G. Incentives for developing resilient agritourism entrepreneurship in rural communities in Romania in a European context. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khampusaen, D.; Naiyanit, B.; Chanprasopchai, T. Transforming Rural Landscapes: Unleashing Agro-Tourism Potential Through Digital Media Interconnectivity. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 2054–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuil, I.; Stăncioiu, E.L.; Ionica, A.C.; Leba, M. Sustainable Agritourism: Integrating Emerging Technologies within Community-Centric Development. Entren. Enterp. Res. Innov. 2024, 10, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andéhn, M.; L’Espoir Decosta, J.P. Authenticity and product geography in the making of the agritourism destination. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1282–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, C.; Padhi, S.S.; Pati, R.K.; Stoleriu, O.M. Tourist choice of heritage sites in Romania: A conjoint choice model of site attributes and variety seeking behavior. J. Herit. Tour. 2021, 16, 646–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tătar, C.F.; Dincă, I.; Linc, R.; Stupariu, M.I.; Bucur, L.; Stașac, M.S.; Nistor, S. Oradea Metropolitan Area as a space of interspecific relations triggered by physical and potential tourist activities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buza, M.; Dimen, L.; Pop, G.; Turnock, D. Environmental protection in the Apuseni Mountains: The role of environmental non-governmental organisations (ENGOs). GeoJournal 2001, 55, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badulescu, D.; Giurgiu, A.; Istudor, N.; Badulescu, A. Rural tourism development and financing in Romania: A supply-side analysis. Agric. Econ. Zemědělská Ekon. 2015, 61, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soare, I.; Dobrea NC, R.C.; Nastase, M. The rural tourist entrepreneurship–new opportunities of capitalizing the rural tourist potential in the context of durable development. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, D.; Batuk, F. Technique for order preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) for spatial decision problems. In Proceedings of the ISPRS, Sydney, Australia, 10–15 April 2011; Volume 1. Available online: https://www.isprs.org/proceedings/2011/gi4dm/pdf/pp12.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Oltean, R.; Chifor, C.; Isarie, V.I.; Arion, I.D.; Muresan, I.C.; Arion, F.H. Environmental and agrifood cultural tradition preservation as part of rural tourism. A systematic literature review in Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2023, 23, 501–516. Available online: https://managementjournal.usamv.ro/pdf/vol.23_2/Art57.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Ispas, A.; Untaru, E.N.; Candrea, A.N. Environmental management practices within agritourism boarding houses in Romania: A qualitative study among managers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]