Spring Oat Yields in Crop Rotation and Continuous Cropping: Reexamining the Need for Crop Protection When Growing Modern Varieties

Abstract

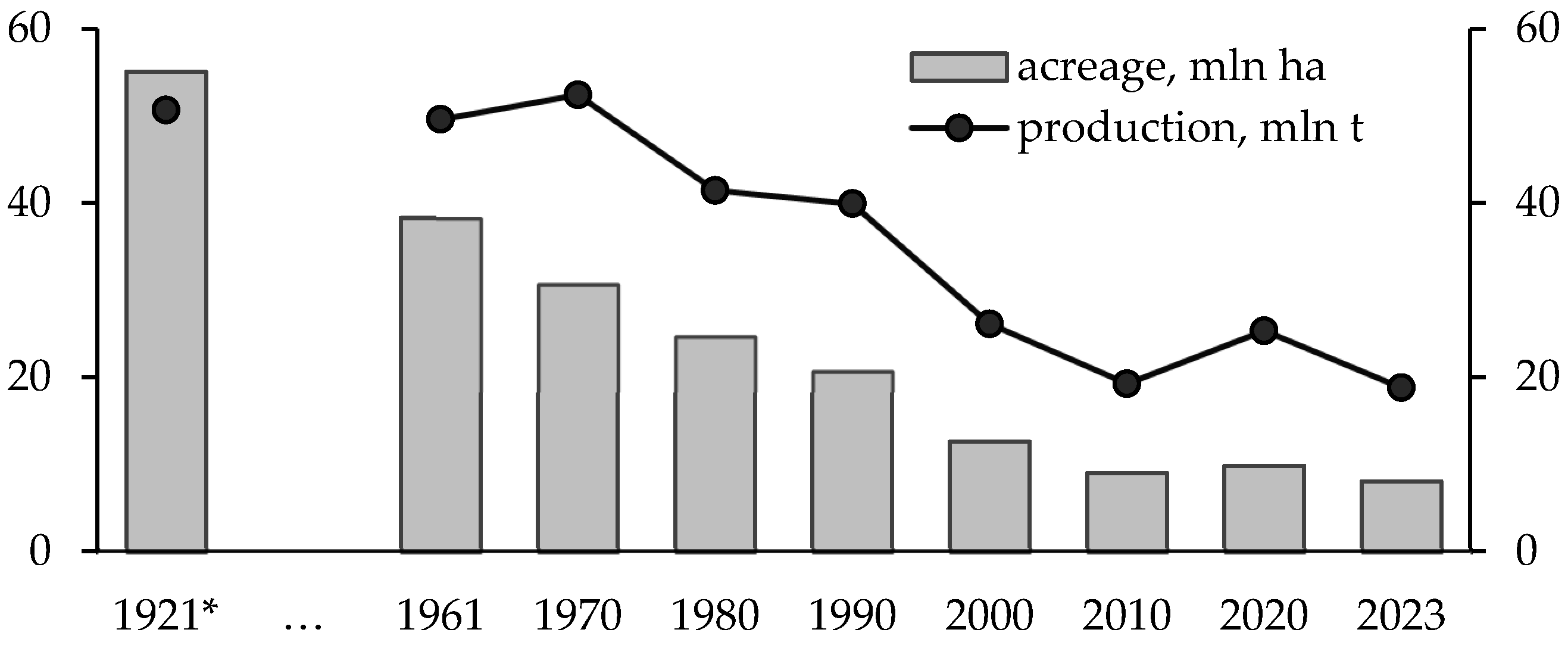

1. Introduction

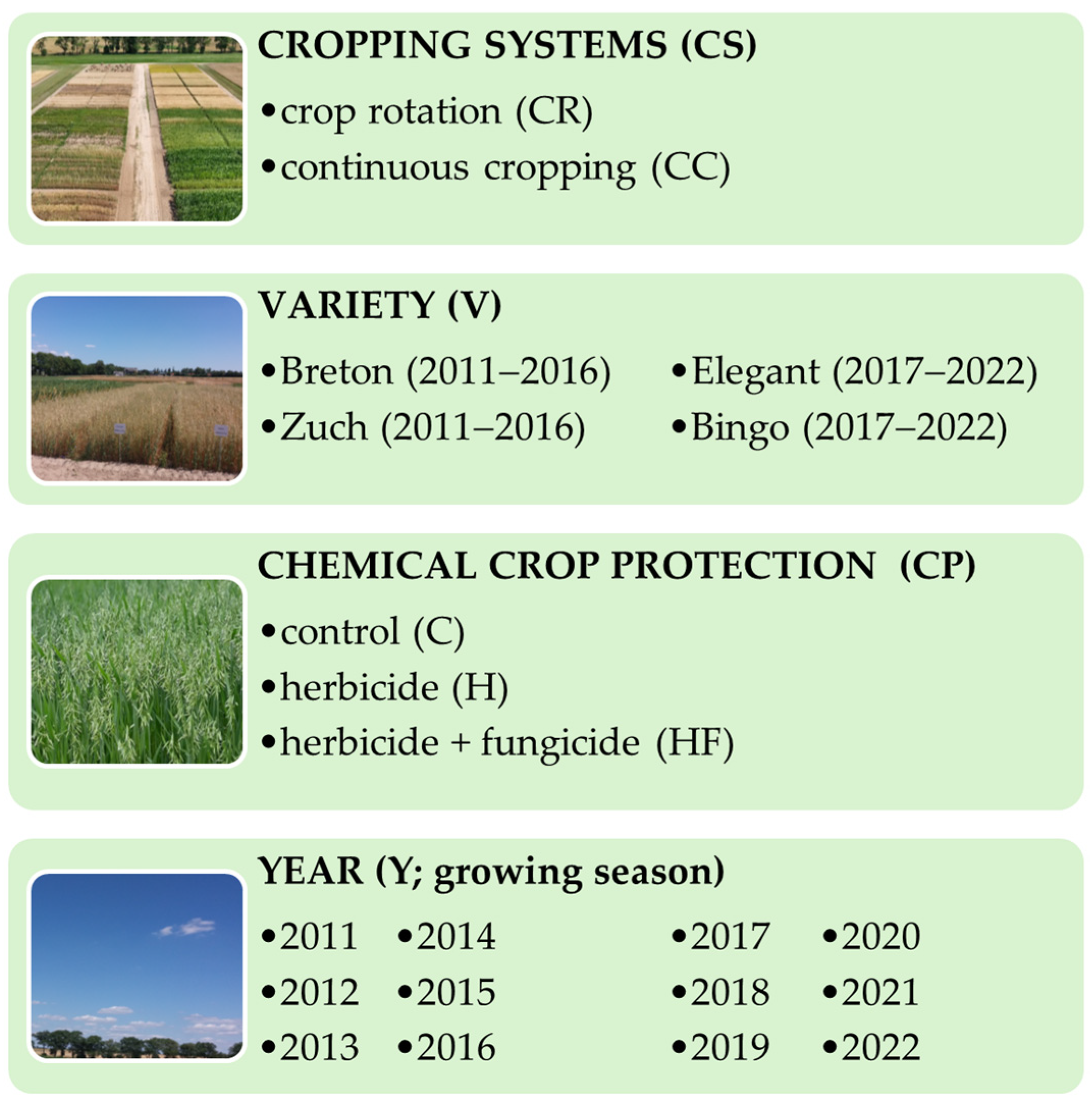

2. Materials and Methods

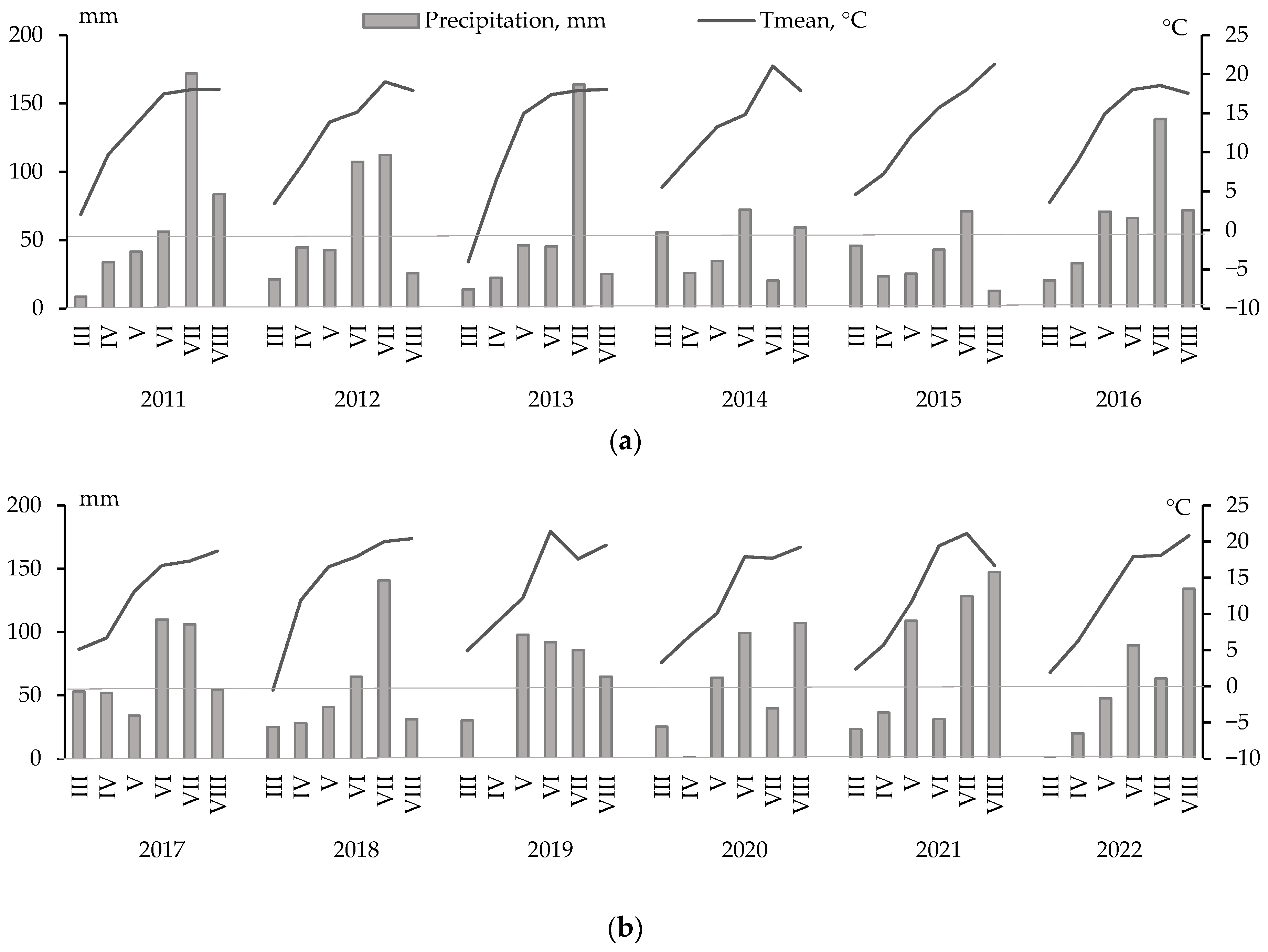

2.1. Study Site and Basic Long-Term Experiment Description

2.2. Study Design and Description

2.3. Agronomic Management and Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

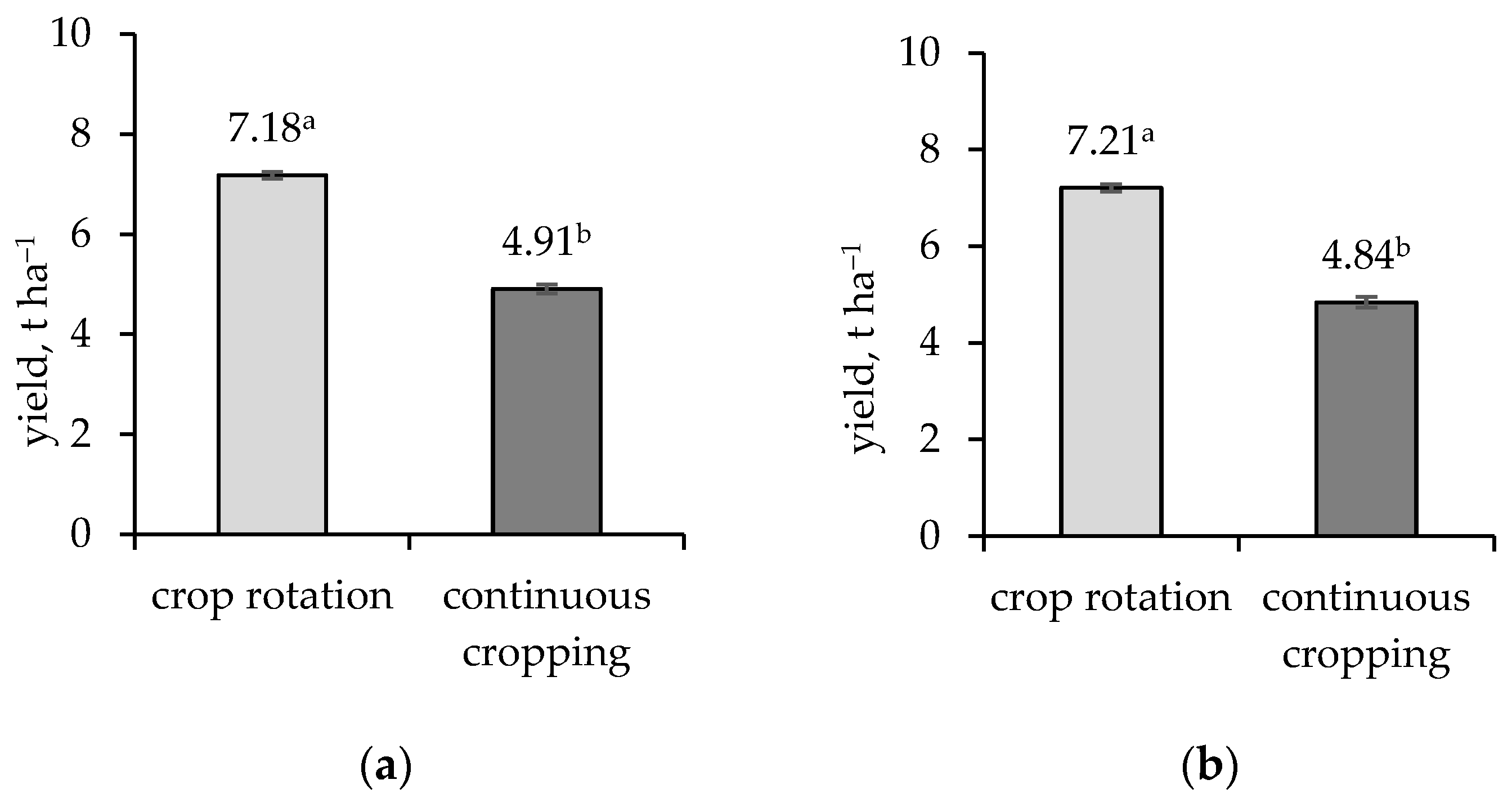

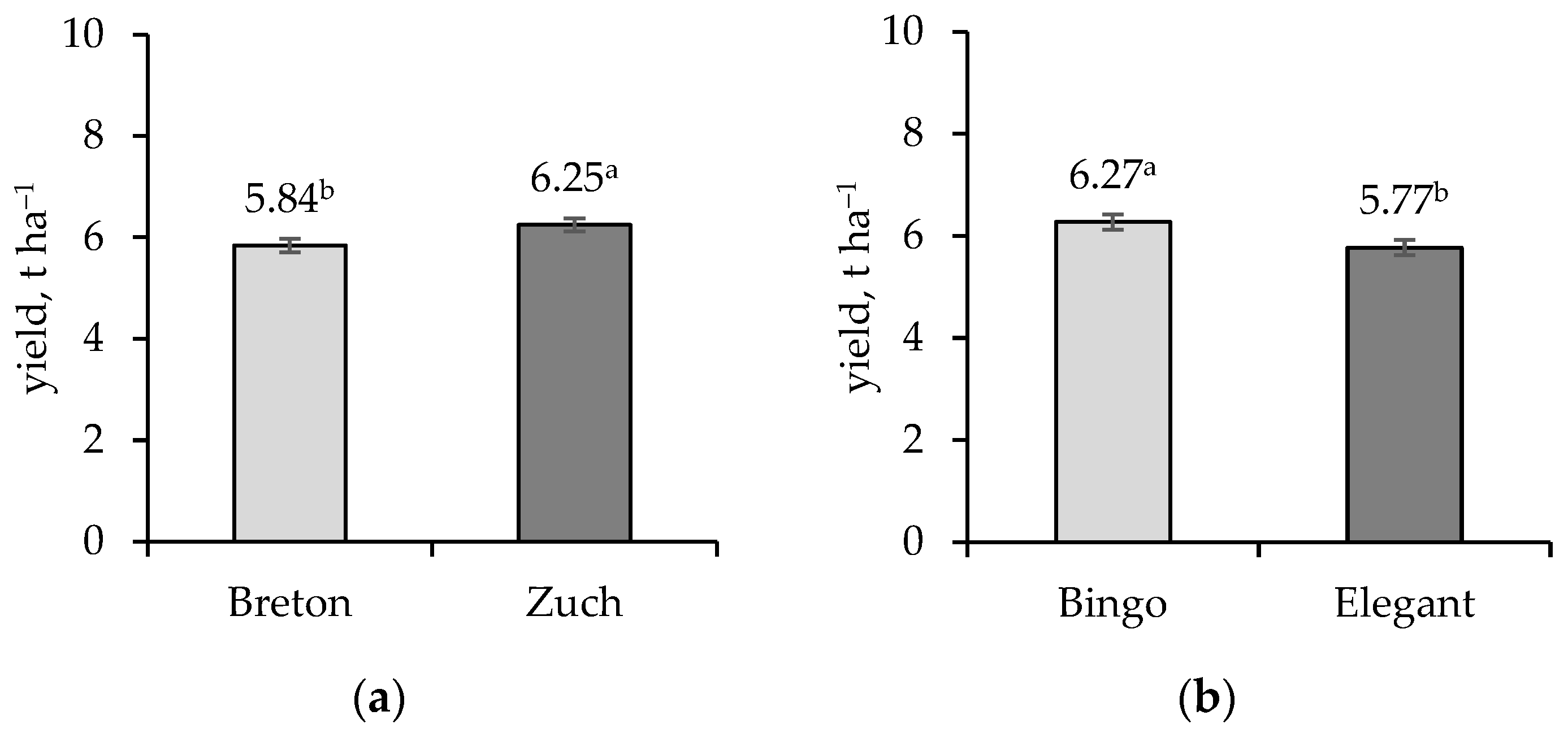

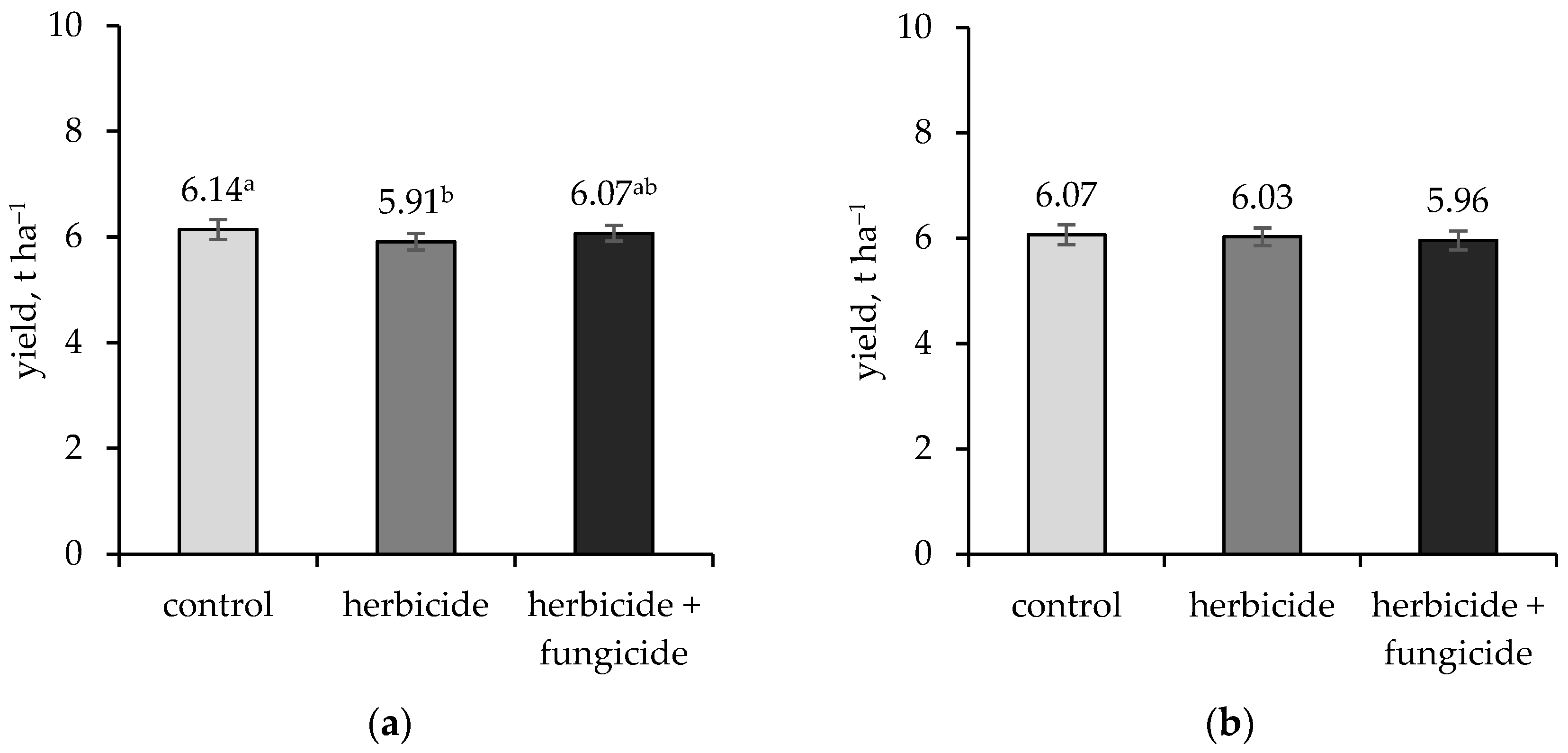

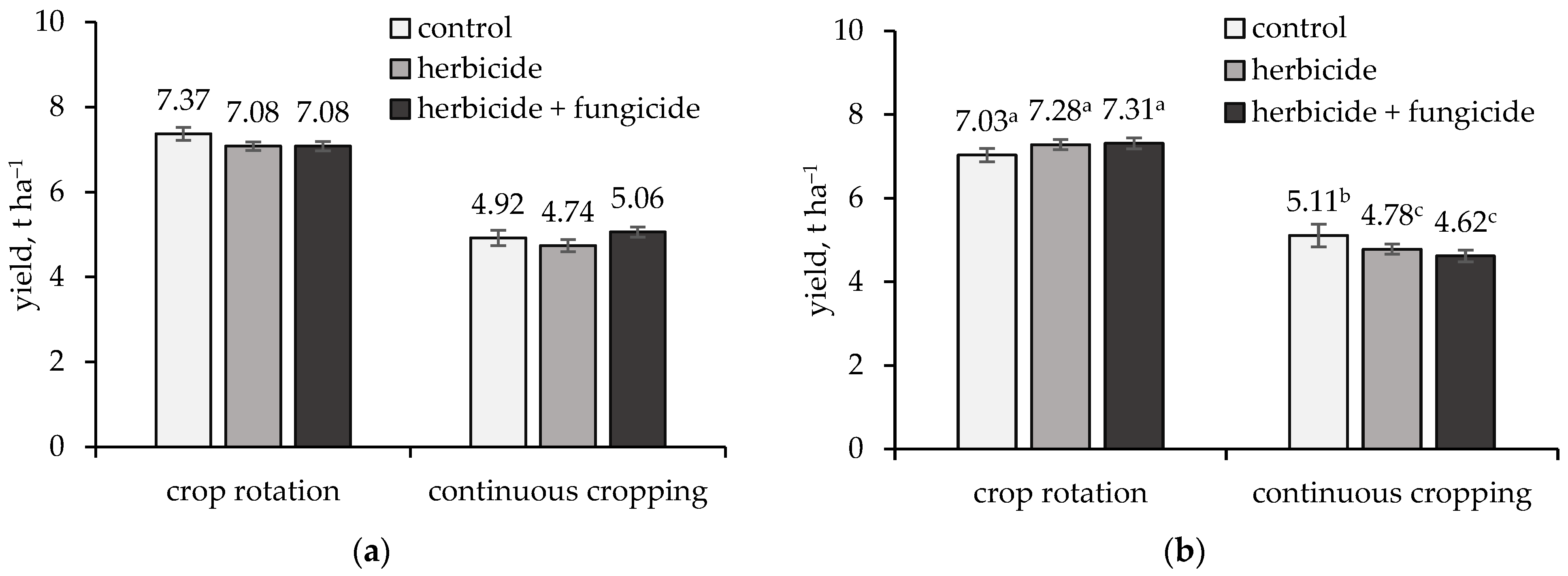

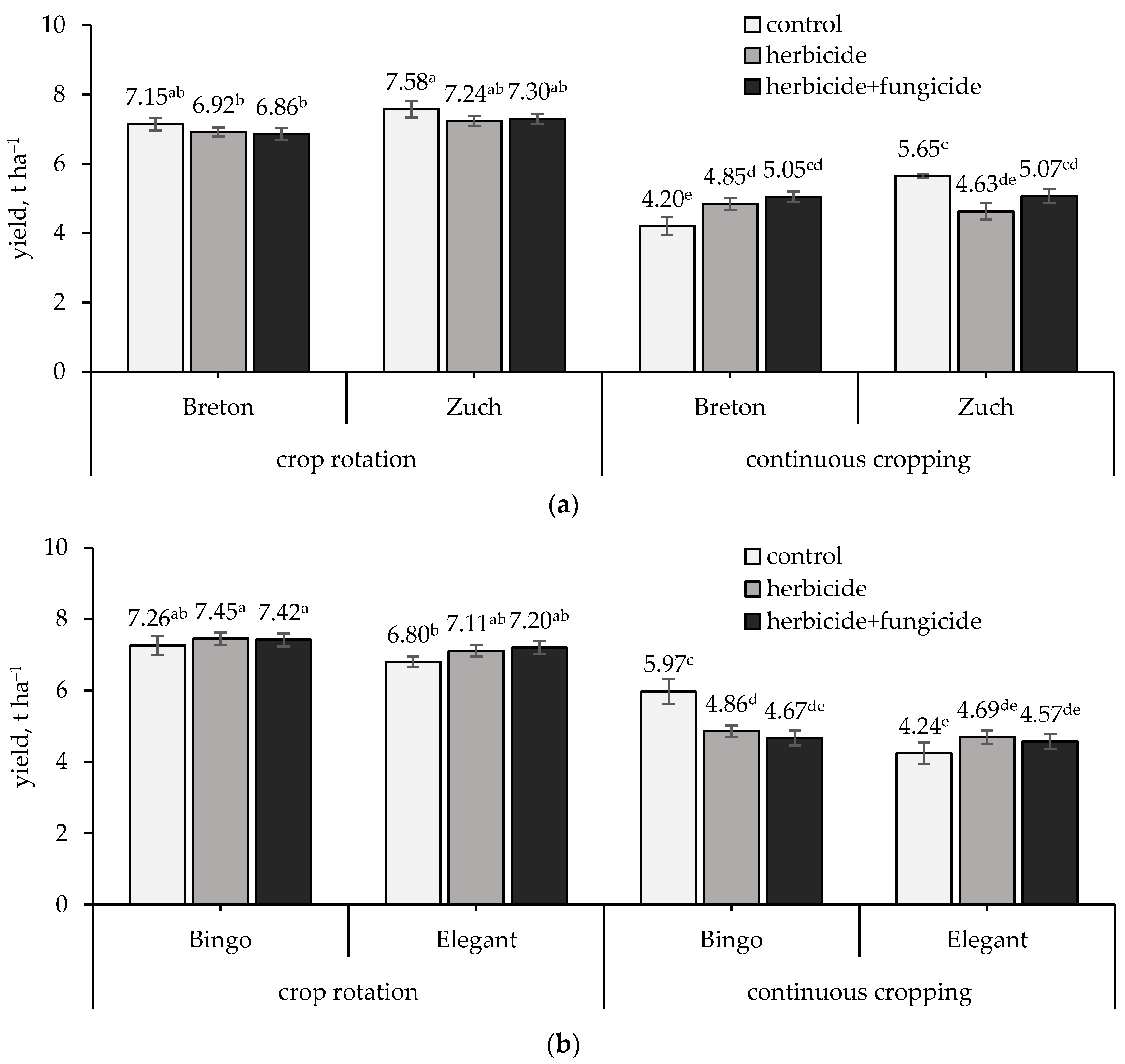

3.1. Individual Effects of the Cropping System, Variety, Crop Protection, and Year Factors

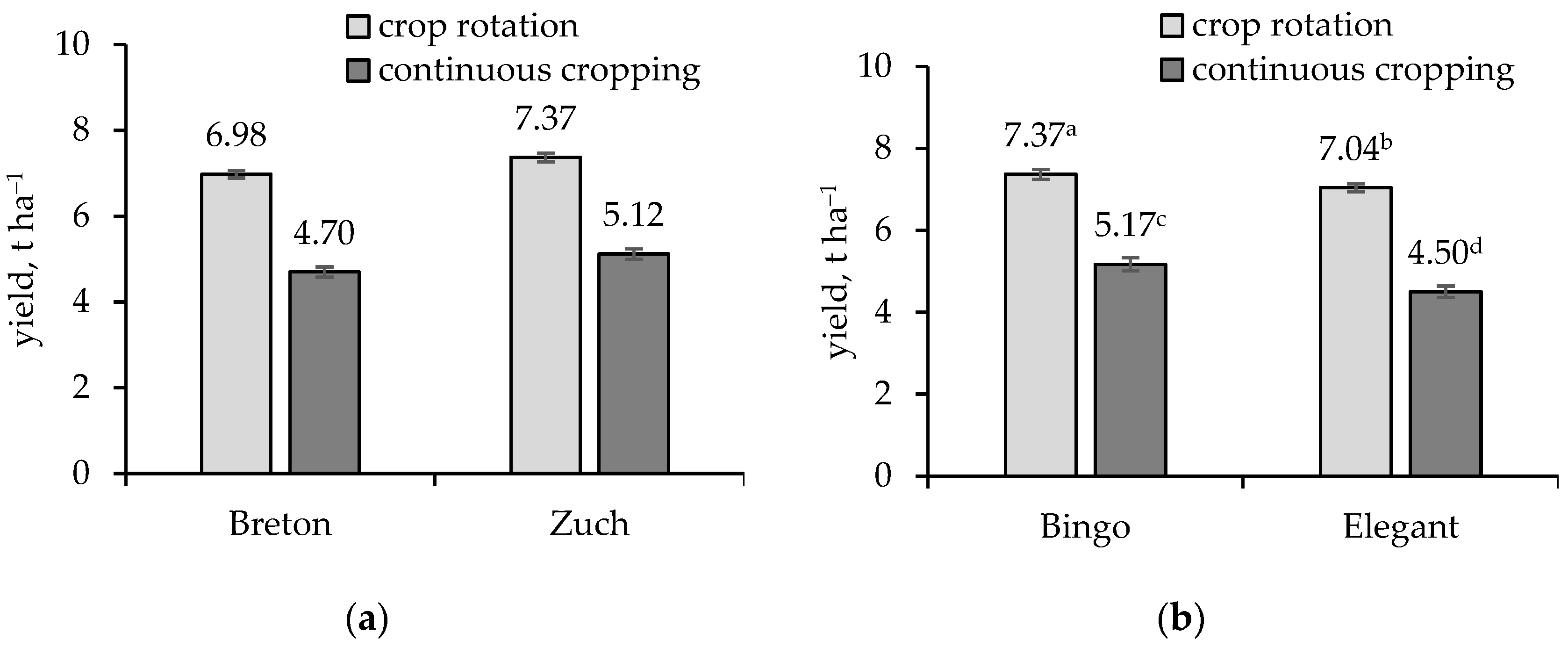

3.2. Interaction Effects Between Experimental Factors

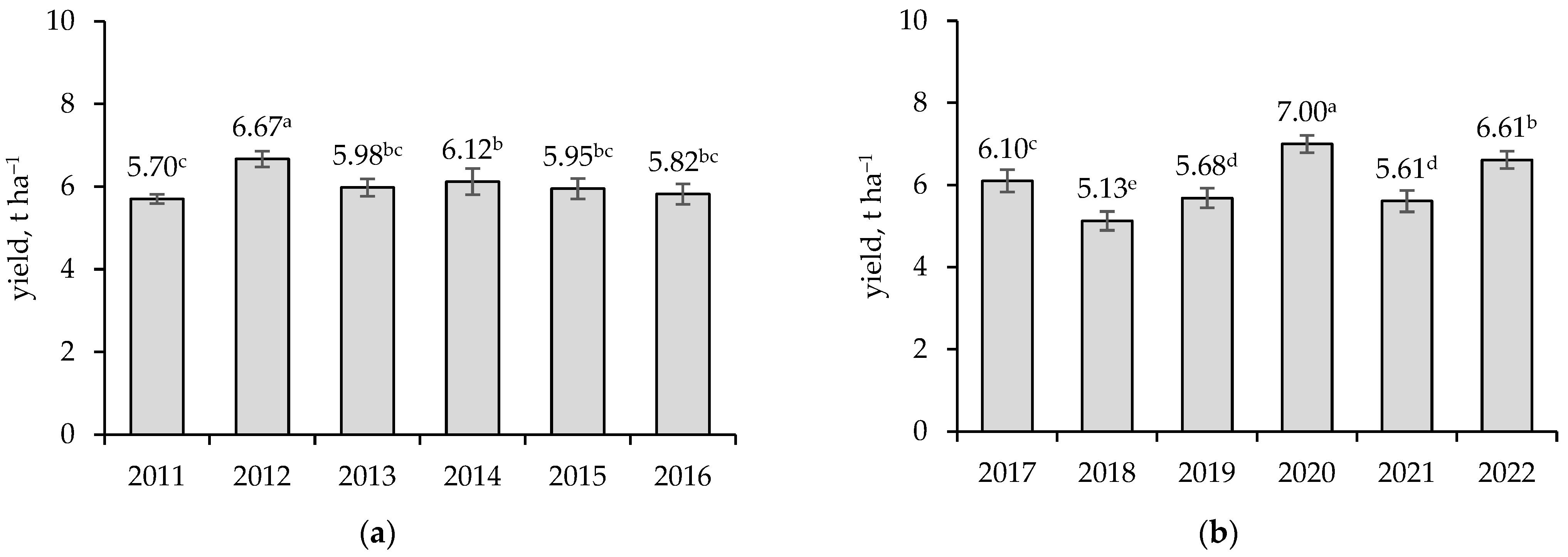

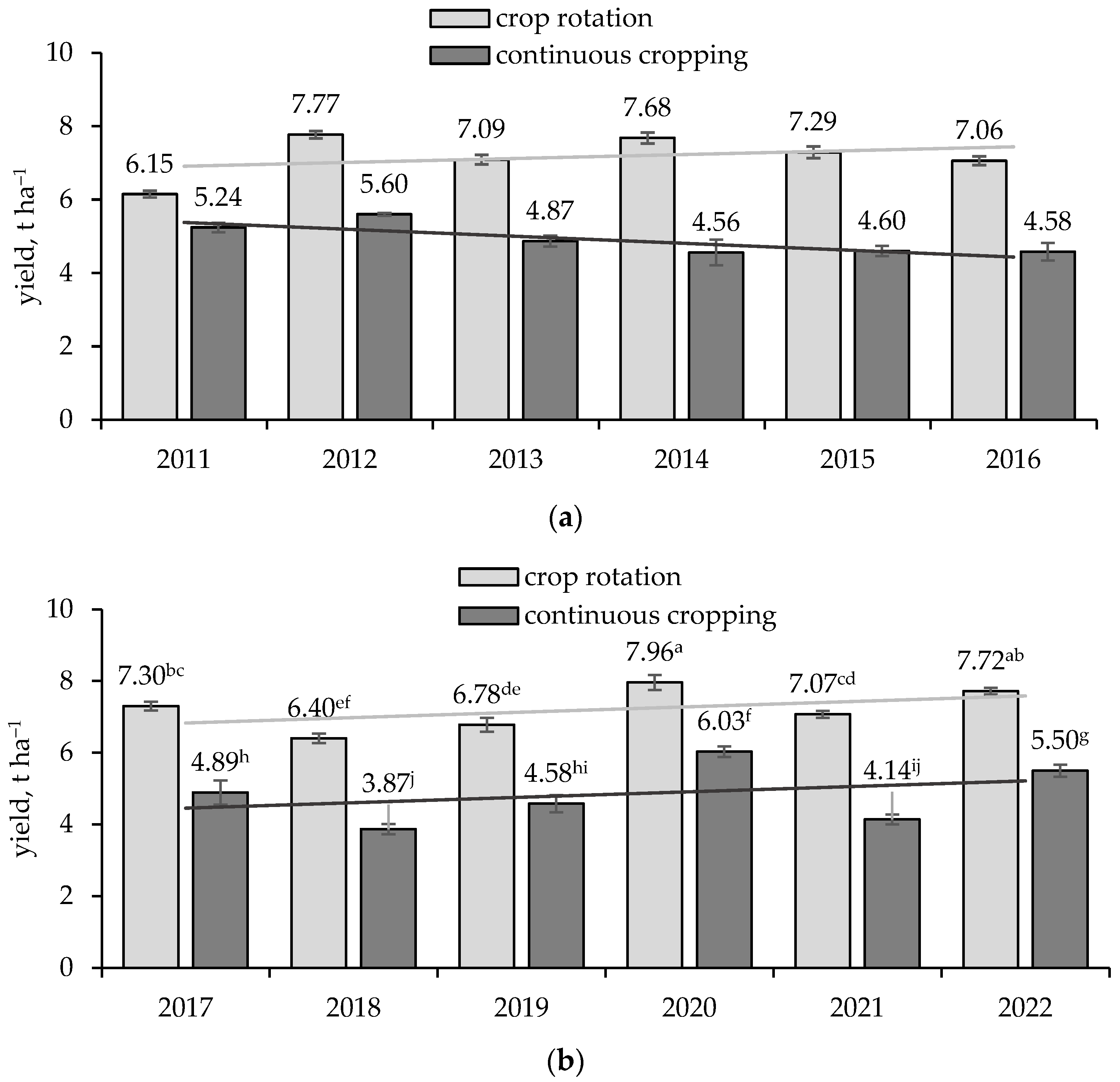

3.3. Interannual Yield Variability

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of the Cropping System, Variety, Crop Protection Factors, and Their Interactions

4.2. Effects of the Year Factor and Interactions Between Year and the Agronomic Factors

4.3. Interannual Yield Variability

4.4. Study Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| C | control treatment |

| CC | continuous cropping |

| COBORU | Centralny Ośrodek Badania Odmian Roślin Uprawnych (Research Center for Cultivar Testing) |

| CP | crop protection |

| CR | crop rotation |

| CS | cropping system |

| CV | variation coefficient |

| FYM | farmyard manure |

| H | herbicide protection |

| HF | herbicide plus fungicide protection |

| NLI | Polish National List (of agricultural plant varieties) |

| V | variety |

| Y | year |

References

- Jain, D.; Singh, P.; Rani, K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Prajapati, A. Oat, a distinct cereal origin, history, production practices, and production economics. In Oat (Avena sativa): Production to Plate; Tomar, M., Singh, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu, G.F.; Forsido, S.F.; Tola, Y.B.; Amare, E. Nutritional and phytochemical composition and associated health benefits of oat (Avena sativa) grains and oat-based fermented food products. Sci. World 2023, 2023, 2730175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorash, A.; Armonienė, R.; Mitchell Fetch, J.; Liatukas, Ž.; Danytė, V. Aspects in oat breeding: Nutrition quality, nakedness and disease resistance, challenges and perspectives. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2017, 171, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowa, S.; Paczos-Grzęda, E. A study of crown rust resistance in historical and modern oat cultivars representing 120 years of Polish oat breeding. Euphytica 2020, 216, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.-L.; Zheng, Z.; Ren, C. Oat. In Crop Physiology Case Histories for Major Crops; Sadras, V.O., Calderini, D.F., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 222–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, L.R.; Murphy, K.M.; Jones, S.S. The history of oats in western Washington and the evolution of regionality in agriculture. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT Database; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Smith, M.E.; Vico, G.; Costa, A.; Bowles, T.; Gaudin, A.C.M.; Hallin, S.; Watson, C.A.; Alarcón, R.; Berti, A.; Blecharczyk, A.; et al. Increasing crop rotational diversity can enhance cereal yields. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holopainen-Mantila, U.; Vanhatalo, S.; Lehtinen, P.; Sozer, N. Oats as a source of nutritious alternative protein. J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 116, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.S.; Hermansen, C.; Vuong, Q.V. Oat Milk By-Product: A review of nutrition, processing and applications of oat pulp. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 1538–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Tomar, M.; Singh, A.K.; Yadav, V.K.; Saini, R.P.; Swami, S.R.; Mahesha, H.S.; Singh, T. International scenario of oat production and its potential role in sustainable agriculture. In Oat (Avena sativa); Tomar, M., Singh, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Inforegio—Smart Regions: The European Project “Re-Cereal” Is Bringing Back Traditional Cereal Crops to Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/newsroom/news/2022/09/09-01-2022-smart-regions-the-european-project-re-cereal-is-bringing-back-traditional-cereal-crops-to-europe (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Healthy Minor Cereals. Available online: https://healthyminorcereals.eu/en/about-project/about (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Koroluk, A.; Sowa, S.; Boczkowska, M.; Paczos-Grzęda, E. Utilizing genomics to characterize the common oat gene pool—The story of more than a century of Polish breeding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtacki, M.; Żuk-Gołaszewska, K.; Gołaszewski, J. Modeling the effects of agronomic factors and physiological and climatic parameters on the grain yield of hulled and hulless oat. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 162, 127425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, K.; Jauhiainen, L.; Rajala, A.A.; Jalli, M.; Kujala, M.; Laine, A. Different responses to weather events may change the cultivation balance of spring barley and oats in the future. Field Crop Res. 2020, 259, 107956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, H.E. Statistics of Oats, Barley, and Grain Sorghums: Year Ended December 31, 1928, with Comparable Data for Earlier Years; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1930.

- Kurowski, T.P. Studia nad Chorobami Podsuszkowymi Zboz Uprawianych w Wieloletnich Monokulturach; Rozprawy i Monografie, 56; Wydawnictwo UWM: Olsztyn; Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski, W. Reakcja owsa siewnego na uprawę w płodozmianach uproszczonych. Biul. Inst. Hod. Aklim. Rośl. 2006, 239, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, E. Struktura Zachwaszczenia i Produktywność Wybranych Agrocenoz Zbóż Ozimych i Jarych w Zależności od Systemu Następstwa Roślin i Ochrony Łanu; Rpzprawy i Monografie, 129; Wydawnictwo UWM: Olsztyn, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adamiak, E.; Adamiak, J. Reaction of oat varieties to the protection level in different crop sequence systems. Prog. Plant Prot. 2013, 53, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecharczyk, A.; Małecka-Jankowiak, I.; Sawińska, Z.; Piechota, T.; Waniorek, W. 60-letnie doświadczenie nawozowe w Brodach z uprawą roślin w zmianowaniu i monokultutrze. In Eksperymenty Wieloletnie w Badaniach Rolniczych w Polsce; Marks, M., Jastrzębska, M., Kostrzewska, M.K., Eds.; Wydawnictwo UWM: Olsztyn, Poland, 2018; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, M.; Rychcik, B.; Treder, K.; Tyburski, J. 50-letnie badania nad uprawą roślin w płodozmianie i monokulturze -źródło wiedzy i pomnik kultury rolnej. In Eksperymenty Wieloletnie w Badaniach Rolniczych w Polsce; Marks, M., Jastrzębska, M., Kostrzewska, M., Eds.; Wydawnictwo UWM: Olsztyn, Poland, 2018; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, A.E.; Poulton, P.R. The importance of long-term experiments in agriculture: Their management to ensure continued crop production and soil fertility; the Rothamsted experience. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 69, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holatko, J.; Brtnicky, M.; Baltazar, T.; Smutny, V.; Frouz, J.; Kintl, A.; Jaskulska, I.; Ryant, P.; Radziemska, M.; Latal, O.; et al. Long-term effects of wheat continuous cropping vs wheat in crop rotation on carbon content and mineralisation, aggregate stability, biological activity, and crop yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 158, 127218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulton, P.R.; Powlson, D.S.; Glendining, M.J.; Gregory, A.S. Why do we make changes to the long-term experiments at Rothamsted? Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 154, 127062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merbach, W.; Deubel, A. Long-term field experiments—Museum relics or scientific challenge? Plant Soil Environ. 2008, 54, 219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Jastrzębska, M.; Kostrzewska, M.K.; Marks, M. Over 50 years of a field experiment on cropping systems in Bałcyny, Poland: Assessing pesticide residues in soil and crops from the perspective of their field application history. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 159, 127270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X. Production and genetic improvement of minor cereals in China. Crop. J. 2017, 5, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostrzewska, M.K.; Jastrzębska, M. Hybrid cultivar and crop protection to support winter rye yield in continuous cropping. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, N.; Yao, X.; He, D.; Sun, H.; Ao, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; St. Martin, S.; Xie, F.; et al. Continuous-cropping-tolerant soybean cultivars alleviate continuous cropping obstacles by improving structure and function of rhizosphere microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1048747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, T.; Manolii, V.P.; Zhou, Q.; Hwang, S.-F.; Strelkov, S.E. Effect of canola (Brassica napus) cultivar rotation on Plasmodiophora brassicae pathotype composition. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2019, 100, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautsalo, J.; Jauhiainen, L.; Hannukkala, A.; Manninen, O.; Veteläinen, M.; Pietilä, L.; Peltoniemi, K.; Jalli, M. Resistance to Fusarium head blight in oats based on analyses of multiple field and greenhouse studies. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 158, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, F.J.; Montilla-Bascón, G.; Gallego-Sánchez, L.M.; Flores, F.; Rispail, N.; Prats, E. Deciphering Main climate and edaphic components driving oat adaptation to Mediterranean environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 780562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chai, J.; Zhao, G.; Zeng, L. Study on the adaptability of 15 oat varieties in different ecological regions. Agronomy 2025, 15, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congruence Market Insights. Oat Seeds Market Trends and Future Opportunities Report [2032]. Available online: https://www.congruencemarketinsights.com/report/oat-seeds-market (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Jastrzębska, M.; Kostrzewska, M.; Saeid, A. Chapter 1—Conventional agrochemicals: Pros and cons. In Smart Agrochemicals for Sustainable Agriculture; Chojnacka, K., Saeid, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowski, T.P.; Adamiak, E. Occurrence of stem base diseases of four cereal species grown in long-term monocultures. Pol. J. Nat. Sci. 2007, 22, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawislak, K.; Adamiak, E. Płodozmlan i pestycydy jako czynniki integrowanej uprawy owsa. Acta Acad. Agric. Tech. Olst. Agric. 1998, 66, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- COBORU. Post-Registration Variety Testing System and Variety Recommendation; Centralny Ośrodek Badania Odmian Roślin Uprawnych: Słupia Wielka, Poland, 2025. Available online: https://www.coboru.gov.pl/pdo (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Noworolnik, K.; Sułek, A. Plonowanie odmian owsa w zależności od warunków glebowych. Pol. J. Agron. 2017, 31, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatSoft. TIBCO Software Inc. Statistica (Data Analysis Software System), Version 13.3; TIBCO Software Inc.: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017.

- Kuś, J.; Smagacz, J. Plonowanie zbóż w zmianowaniach z różnym ich udziałem w trwałym doświadczeniu w Grabowie. In Eksperymenty Wieloletnie w Badaniach Rolniczych w Polsce; Marks, M., Jastrzębska, M., Kostrzewska, M., Eds.; Wydawnictwo UWM: Olsztyn, Poland, 2018; pp. 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Pervaiz, Z.H.; Iqbal, J.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, D.; Wei, H.; Saleem, M. Continuous Cropping Alters multiple biotic and abiotic indicators of soil health. Soil Syst. 2020, 4, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koper, J.; Maniewska, R.; Piotrowska, A.; Kaszeska, J. Nastepcze oddzialywanie zmianowania tradycyjnego i monokultury na stan fitosanitarny gleby pod uprawa owsa siewnego (Avena sativa L.). Zesz. Probl. Post. Nauk. Rol. 2003, 492, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, A. Effect of crop rotation and cereal monoculture on the yield and quality of winter wheat grain and on crop infestation with weeds and soil properties. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2019, 13, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwiercz, A.T.; Zatoń, K.K.; Adamiak, E.; Szelągowska, P.; Hury, G. Plant parasitic nematodes in the soil and roots of winter wheat grown in crop rotation and long–term monoculture. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2018, 58, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, M.; Tritean, N.; Racz, I.; Kadar, R.; Russu, F.; Fițiu, A.; Muntean, E.; Vâtcă, A. Yield performance of spring oats varieties as a response to fertilization and sowing distance. Agronomy 2021, 11, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feledyn-Szewczyk, B.; Kuś, J.; Stalenga, J.; Berbeć, A.K.; Radzikowski, P. The role of biological diversity in agroecosystems and organic farming. In Organic Farming—A Promising Way of Food Production; Konvalina, P., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Li, Z.; Guo, H.; Chen, B.; Wang, T.; Miao, F.; Yang, C.; Xiong, W.; Sun, J. Annual weeds suppression and oat forage yield responses to crop density management in an oat-cultivated grassland: A case study in Eastern China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawislak, K. Regulacyjna funkcja płodozmianu wobec chwastów w agrofitocenozach zbóż. Acta Acad. Agric. Techn. Olst. Agric. 1997, 64, 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- May, W.E.; Ames, N.; Irvine, R.B.; Kutcher, H.R.; Lafond, G.P.; Shirtliffe, S.J. Are fungicide applications to control crown rust of oat beneficial? Can. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 94, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, W.E.; Brandt, S.; Hutt-Taylor, K. Response of oat grain yield and quality to nitrogen fertilizer and fungicides. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehlert, D.C.; McMullen, M.S.; Hammond, J.J. Genotypic and environmental effects on grain yield and quality of oat grown in North Dakota. Crop. Sci. 2001, 41, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, K. Genetic responses of oat genotypes to environmental factors. Field Crop. Res. 1998, 56, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecio, A.; Bichonski, A. Nitrogen fertilization and fungicide application as elements of oat production. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 19, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, J. Weed suppression by cereals: Beyond ‘competitive ability’. Weed Res. 2023, 63, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storkey, J.; Neve, P. What good is weed diversity? Weed Res. 2018, 58, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, C.D.; Wong, M.L.; Carr, P.M.; Seipel, T. Cool semi-arid cropping treatments alter Avena fatua’s performance and competitive intensity. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2024, 3, e12078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupnicka-Rodzynkiewicz, E.; Stepnik, K.; Lepiarczyk, A. Wpływ zmianowania, sposobu uprawy roli i herbicydów na bioróżnorodność zbiorowisk chwastów. Acta Sci. Pol. Agric. 2004, 3, 235–245. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Xiong, X.; Tan, L.; Deng, Y.; Du, X.; Yang, X.; Hu, Q. Soil microbial community assembly and stability are associated with potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) fitness under continuous cropping regime. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1000045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; He, D.; Zhao, X.; Tan, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xie, F.; Wang, J. Integrated microbiology and metabolomics analysis reveal how tolerant soybean cultivar adapt to continuous cropping. Agronomy 2025, 15, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chloupek, O.; Hrstkova, P.; Schweigert, P. Yield and its stability, crop diversity, adaptability and response to climate change, weather and fertilisation over 75 years in the Czech Republic in comparison to some European countries. Field Crop. Res. 2004, 85, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, L.; St-Martin, A.; Vico, G.; Baldoni, G.; Berti, A.; Blecharczyk, A.; Malecka-Jankowiak, I.; Morari, F.; Sawinska, Z.; Bommarco, R. Crop rotations sustain cereal yields under a changing climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 124011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Musawi, Z.K.; Vona, V.; Kulmány, I.M. Utilizing different crop rotation systems for agricultural and environmental sustainability: A review. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Location | North-eastern Poland, 53.60° N, 19.85° E, 136.9 m above sea level; Agricultural Experiment Station in Bałcyny, Poland, owned by the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Poland (formerly the Academy of Agriculture and Technology) |

| Landforms | slight undulations of post-glacial origin |

| Climate | temperate (Cfb according to the Köppen climate classification); mean annual air temperature—8.1 °C, mean yearly precipitation—614.6 mm (Table S2); high weather variability, interannual variations in seasonal patterns (irregular, brief periods of drought, mostly in July and August, and heavy precipitation) |

| Soil type | Luvisols formed from silty light clay |

| Characteristics | Unit | Breton | Zuch | Bingo | Elegant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breeder/maintainer | DANKO Hodowla Roślin sp. z o.o. | Hodowla Roślin Strzelce sp. z o.o. Grupa IHAR | |||

| Entry into NLI 1 | year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2016 |

| COBORU tests | years | 2007–2018 | 2008–2016 | 2009–2022 | 2016–2020 |

| Germination ability | % | 90–99 | 90–100 | 90–98 | 92–99 |

| 1000-grain weight | g | 35.0–43.1 | 33.5–44.0 | 39.2–47.8 | 36.1–41.0 |

| Plant height | cm | 88–115 | 90–119 | 90–117 | 92–109 |

| Heading (from 1.01) | days | 154–170 | 160–172 | 152–168 | 154–166 |

| Wax maturity (from 1.01) | days | 196–213 | 201–211 | 196–213 | 197–213 |

| Resistance to lodging | 9-point scale | 5.5–7.2 | 5.6–7.3 | 5.6–7.3 | 5.9–7.3 |

| Resistance to diseases | 9-point scale | ||||

| —Blumeria graminis | 6.8–8.2 | 6.9–8.0 | 7.1–8.4 | 6.1–8.2 | |

| —Puccinia coronata | 7.0–8.2 | 6.5–8.2 | 7.0–8.2 | 7.4–7.8 | |

| —Pyrenophora avenae | 7.3–8.0 | 7.2–7.9 | 7.2–7.9 | 7.1–7.8 | |

| —Septoria tritici | 6.8–8.4 | 7.3–8.1 | 7.0–8.1 | 7.3–7.9 | |

| Grain yield with hulls | t ha–1 | 5.63–7.30 | 5.78–7.59 | 5.75–7.77 | 5.61–6.84 |

| Hull percentage | % | 23.6–27.8 | 23.2–28.2 | 22–27.7 | 20.3–28.4 |

| Year | Sowing | Harvest | Year | Sowing | Harvest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| the 2011–2016 cycle | the 2017–2022 cycle | ||||

| 2011 | 31 March | 17 August | 2017 | 31 March | 13 August |

| 2012 | 26 March | 6 August | 2018 | 6 April | 25 July |

| 2013 | 19 April | 6 August | 2019 | 28 March | 31 July |

| 2014 | 11 March | 2 August | 2020 | 28 March | 31 July |

| 2015 | 18 March | 14 August | 2021 | 28 March | 31 July |

| 2016 | 30 March | 12 August | 2022 | 26 March | 28 July |

| Source of Variation | Degrees of Freedom | For the 2011–2016 Cycle | For the 2017–2022 Cycle | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | ||

| Cropping system (CS) | 1 | 856.34 | <0.001 | 1431.98 | <0.001 |

| Variety (V) | 1 | 27.81 | <0.001 | 64.27 | <0.001 |

| Crop protection (CP) | 2 | 3.23 | 0.042 | 0.95 | 0.391 |

| Year (Y) | 5 | 13.37 | <0.001 | 80.87 | <0.001 |

| CS × V | 1 | 0.01 | 0.906 | 6.87 | 0.010 |

| CS × CP | 2 | 2.82 | 0.063 | 13.49 | <0.001 |

| V × CP | 2 | 12.25 | <0.001 | 22.50 | <0.001 |

| CS × Y | 5 | 15.57 | <0.001 | 4.93 | <0.001 |

| V × Y | 5 | 3.00 | 0.013 | 6.13 | <0.001 |

| CP × Y | 10 | 1.42 | 0.179 | 1.97 | 0.040 |

| CS × V × CP | 2 | 10.44 | <0.001 | 13.93 | <0.001 |

| CS × V × Y | 5 | 0.86 | 0.509 | 5.70 | <0.001 |

| CS × CP × Y | 10 | 0.73 | 0.699 | 1.98 | 0.040 |

| V × CP × Y | 10 | 3.48 | <0.001 | 3.93 | <0.001 |

| CS × V × CP × Y | 10 | 0.69 | 0.729 | 12.36 | <0.001 |

| Crop Rotation Cycle | Cropping System (CS) | Variety (V) | Chemical Crop Protection (CP) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (C) | Herbicide (H) | Herbicide + Fungicide (HF) | |||

| 2011–2016 | Crop rotation (CR) | Breton | 8.4 | 6.5 | 8.0 |

| Zuch | 12.3 | 5.9 | 6.8 | ||

| Continuous cropping (CC) | Breton | 25.0 | 6.2 | 6.2 | |

| Zuch | 3.9 | 13.0 | 9.5 | ||

| 2017–2022 | Crop rotation (CR) | Bingo | 14.4 | 8.1 | 8.6 |

| Elegant | 8.7 | 7.2 | 9.1 | ||

| Continuous cropping (CC) | Bingo | 23.8 | 11.7 | 15.3 | |

| Elegant | 29.0 | 14.6 | 13.7 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jastrzębska, M.; Kostrzewska, M.K.; Marks, M. Spring Oat Yields in Crop Rotation and Continuous Cropping: Reexamining the Need for Crop Protection When Growing Modern Varieties. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242618

Jastrzębska M, Kostrzewska MK, Marks M. Spring Oat Yields in Crop Rotation and Continuous Cropping: Reexamining the Need for Crop Protection When Growing Modern Varieties. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242618

Chicago/Turabian StyleJastrzębska, Magdalena, Marta K. Kostrzewska, and Marek Marks. 2025. "Spring Oat Yields in Crop Rotation and Continuous Cropping: Reexamining the Need for Crop Protection When Growing Modern Varieties" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242618

APA StyleJastrzębska, M., Kostrzewska, M. K., & Marks, M. (2025). Spring Oat Yields in Crop Rotation and Continuous Cropping: Reexamining the Need for Crop Protection When Growing Modern Varieties. Agriculture, 15(24), 2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242618