Development of an Innovative Mechanical–Aeraulic Device for Sustainable Vector Control of Nymphs of Philaenus spumarius

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Components of the Developed Mechanical–Aeraulic Device

2.1.1. Motorized Agricultural Wheelbarrow

2.1.2. Employed Air Heaters

2.2. Design and Construction of the Mechanical–Aeraulic Device

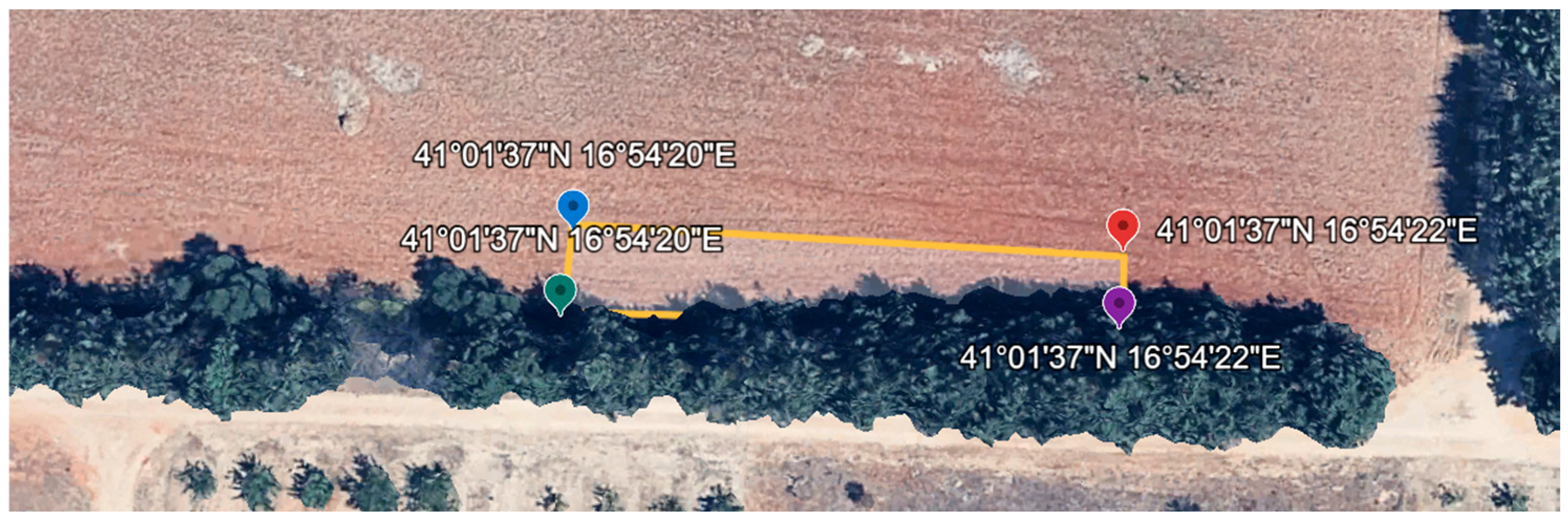

2.3. Field Tests

3. Results

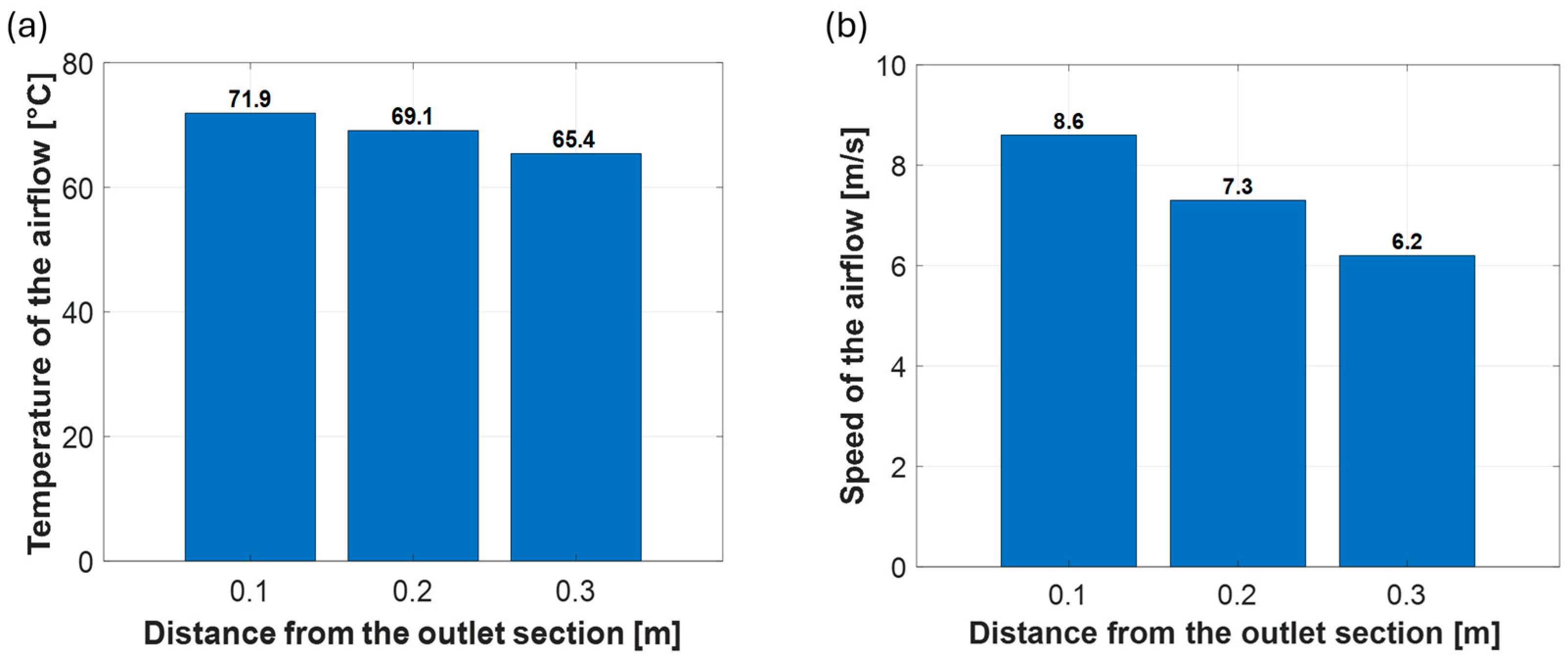

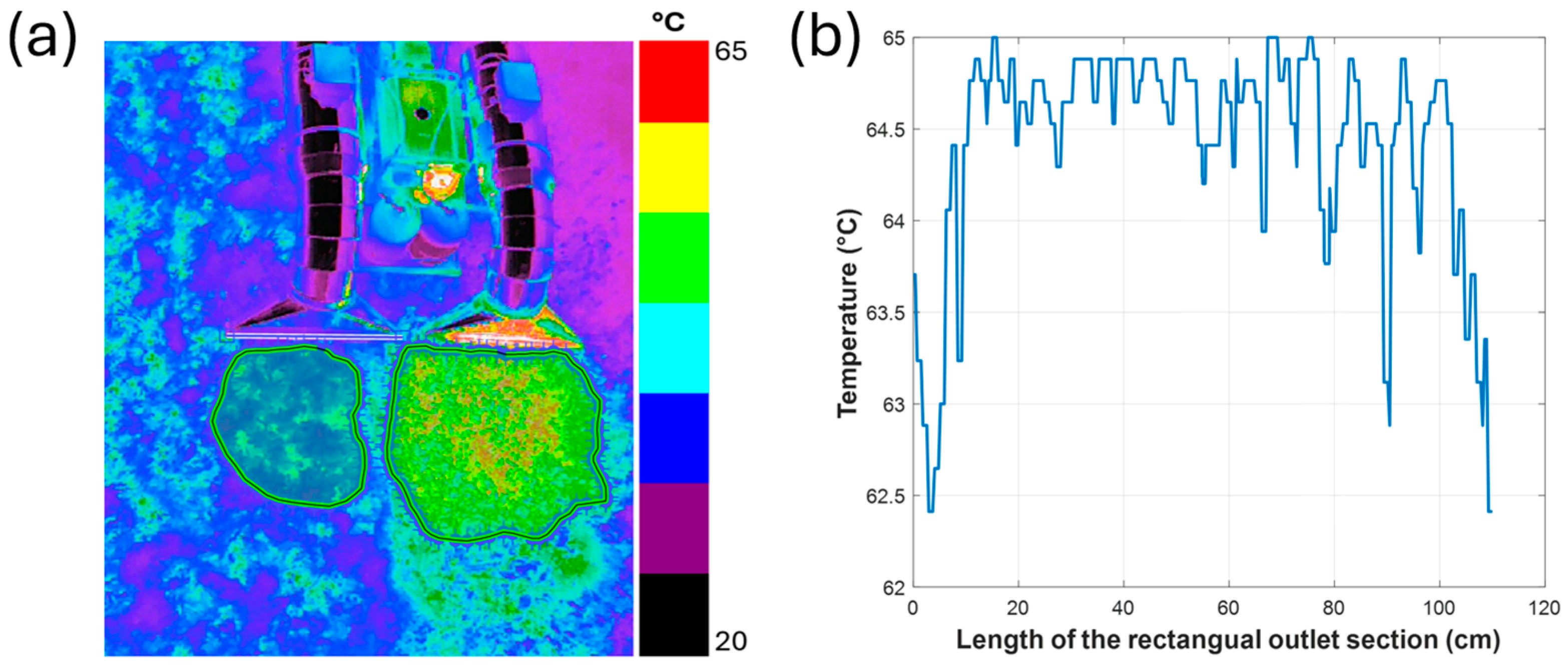

3.1. Characterization of the Developed Mechanical–Aeraulic Device

3.2. Effectiveness of the Employed Method Against Nymphs of P. spumarius

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanism of Action of the Proposed Physical Vector Control Strategy

4.2. Technical Performance of the Developed Mechanical–Aeraulic Device

4.3. Comparison of the Employed Method with Control Strategies Based on Chemical Insecticides and Natural Compounds

4.4. Economic Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| OQDS | Olive Quick Decline Syndrome |

| EC | European Commission |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| IPM | Integrated Pest Management |

| LPG | Liquefied Petroleum Gas |

| LHV | Lower Heating Value |

References

- Wells, J.M.; Raju, B.C.; Hung, H.-Y.; Weisburg, W.G.; Mandelco-Paul, L.; Brenner, D.J. Xylella fastidiosa gen. nov., sp. nov:Gram-negative, xylem-limited, fastidious plant bacteria related to Xanthomonas spp. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1987, 37, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, D. Xylella fastidiosa: Xylem-Limited Bacterial Pathogen of Plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1989, 27, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.P.; Blua, M.J.; Lopes, J.R.; Purcell, A.H. Vector transmission of Xylella fastidiosa: Applying fundamental knowledge to generate disease management strategies. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2005, 98, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeger, M.; Caffier, D.; Candresse, T.; Chatzivassiliou, E.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Gilioli, G.; Grégoire, J.; Jaques Miret, J.A.; MacLeod, A.; Navajas Navarro, M.; et al. Updated pest categorisation of Xylella fastidiosa. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Attoma, G.; Morelli, M.; De La Fuente, L.; Cobine, P.A.; Saponari, M.; de Souza, A.A.; De Stradis, A.; Saldarelli, P. Phenotypic Characterization and Transformation Attempts Reveal Peculiar Traits of Xylella fastidiosa Subspecies pauca Strain De Donno. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, G.P. The current status of the quick decline syndrome of olive in southern Italy. Phytoparasitica 2015, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saponari, M.; Loconsole, G.; Cornara, D.; Yokomi, R.K.; De Stradis, A.; Boscia, D.; Bosco, D.; Martelli, G.P.; Krugner, R.; Porcelli, F. Infectivity and Transmission of Xylella fastidiosa by Philaenus spumarius (Hemiptera: Aphrophoridae) in Apulia, Italy. J. Econ. Entomol 2014, 107, 1316–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, H.; Pingel, M.; Voigt, D.; Wyss, U.; Gorb, S. Adhesive properties of Aphrophoridae spittlebug foam. J. R. Soc. Interface 2024, 21, 20230521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, M.; Gomes, G.; Silva, W.D.; Magri, N.T.C.; Vieira, D.M.; Aguiar, C.L.; Bento, J.M.S. Spittlebugs produce foam as a thermoregulatory adaptation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EU). Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2015/789 of 18 May 2015 as regards measures to prevent the introduction into and the spread within the Union of Xylella fastidiosa (Wells et al.). Off. J. Eur. Union 2015, 125, 36–53. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EU). Commission implementing regulation (EU) 2020/1201 of 14 August 2020, as regards measures to prevent the introduction into and the spread within the Union of Xylella fastidiosa (Wells et al.). Off. J. Eur. Union 2020, 269, 2–39. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, R.P.; Nunney, L. How Do Plant Diseases Caused by Xylella fastidiosa Emerge? Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regional Government Decisions No. 1866/2022 and 570. Available online: https://burp.regione.puglia.it/documents/20135/2174105/DEL_590_2023.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Labadessa, R.; Adamo, M.; Tarantino, C.; Vicario, S. The side effects of the cure: Large-scale risks of a phytosanitary action plan on protected habitats and species. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Regional Council Resolution No. 1593/2024. Available online: https://burp.regione.puglia.it/documents/20135/2560952/DEL_1593_2024.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Del Coco, L.; Migoni, D.; Girelli, C.R.; Angilè, F.; Scortichini, M.; Fanizzi, F.P. Soil and Leaf Ionome Heterogeneity in Xylella fastidiosa Subsp. Pauca-Infected, Non-Infected and Treated Olive Groves in Apulia, Italy. Plants 2020, 9, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; García-Madero, J.M.; Jos, Á.; Saldarelli, P.; Dongiovanni, C.; Kovacova, M.; Saponari, M.; Baños Arjona, A.; Hackl, E.; Webb, S.; et al. Xylella fastidiosa in olive: A review of control attempts and current management. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleve, G.; Gallo, A.; Altomare, C.; Vurro, M.; Maiorano, G.; Cardinali, A.; D’Antuono, I.; Marchi, G.; Mita, G. In vitro activity of antimicrobial compounds against Xylella fastidiosa, the causal agent of the olive quick decline syndrome in Apulia (Italy). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 365, fnx281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.L.; Courtenay, O.; Kelly-Hope, L.A.; Scott, T.W.; Takken, W.; Torr, S.J.; Lindsay, S.W. The importance of vector control for the control and elimination of vector-borne diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0007831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, B.L.; Purcell, A.H. Populations of Xylella fastidiosa in plants required for transmission by an efficient vector. Phytopathology 1997, 87, 1197–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornara, D.; Saponari, M.; Zeilinger, A.R.; De Stradis, A.; Boscia, D.; Loconsole, G.; Bosco, D.; Martelli, G.P.; Almeida, R.P.P.; Porcelli, F. Spittlebugs as vectors of Xylella fastidiosa in olive orchards in Italy. J. Pest. Sci. 2017, 90, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.; Santos, S. Sustainable approach to weed management: The role of precision weed management. Agronomy 2022, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serio, F.D.; Bodino, N.; Cavalieri, V.; Demichelis, S.; Carolo, M.D.; Dongiovanni, C.; Fumarola, G.; Gilioli, G.; Guerrieri, E.; Picciotti, U.; et al. Collection of data and information on biology and control of vectors of Xylella fastidiosa. EFSA Support. Publ. 2019, 16, 1628E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongiovanni, C.; Di Carolo, M.; Fumarola, G.; Tauro, D.; Altamura, G.; Cavalieri, V. Evaluation of insecticides for the control of juveniles of Philaenus spumarius L., 2015–2017. Arthropod Manag. Tests 2018, 43, tsy073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dáder, B.; Viñuela, E.; Moreno, A.; Plaza, M.; Garzo, E.; Del Estal, P.; Fereres, A. Sulfoxaflor and natural Pyrethrin with Piperonyl Butoxide are effective alternatives to Neonicotinoids against juveniles of Philaenus spumarius, the european vector of Xylella fastidiosa. Insects 2019, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, A.; Zeilinger, A.R.; Vanhove, M.; Schartel, T.E.; Beal, D.J.; Daugherty, M.P.; Almeida, R.P. Xylella fastidiosa: Insights into an emerging plant pathogen. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018, 56, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, E.; Ruschioni, S.; Riolo, P.; Isidoro, N.; Romani, R. Fine structure of antennal sensilla of the spittlebug Philaenus spumarius L. (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aphrophoridae). I. Chemoreceptors and thermo-/hygroreceptors. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2016, 45, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avosani, S.; Franceschi, P.; Ciolli, M.; Verrastro, V.; Mazzoni, V. Vibrational playbacks and microscopy to study the signalling behaviour and female physiology of Philaenus spumarius. J. Appl. Entomol. 2021, 145, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Industrial Dehumidification, Cooling & Air Quality Solutions|Munters. Available online: https://www.munters.com/it-it/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Webley, N. Air Heaters. In The Coen &: Hamworthy Combustion Handbook; Taylor and Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; pp. 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciolla, F.; Popeo, G.; Farella, A.; Pascuzzi, S. Agronomic Information Extraction from UAV-Based Thermal Photogrammetry Using MATLAB. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacaze, B.; Dudek, J.; Picard, J. Grass gis software with qgis. In QGIS and Generic Tools; Wiley-ISTE: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 67–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chartois, M.; Mesmin, X.; Quiquerez, I.; Borgomano, S.; Farigoule, P.; Pierre, E.; Thuillier, J.; Streito, J.; Casabianca, F.; Hugot, L.; et al. Environmental factors driving the abundance of Philaenus spumarius in mesomediterranean habitats of Corsica (France). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongiovanni, C.; Cavalieri, V.; Bodino, N.; Tauro, D.; Di Carolo, M.; Fumarola, G.; Altamura, G.; Lasorella, C.; Bosco, D. Plant selection and population trend of spittlebug immatures (Hemiptera: Aphrophoridae) in olive groves of the Apulia region of Italy. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terblanche, J.S.; Clusella-Trullas, S.; Deere, J.A.; Chown, S.L. Thermal tolerance in a south-east African population of the tsetse fly Glossina pallidipes (Diptera, Glossinidae): Implications for forecasting climate change impacts. J. Insect Physiol. 2008, 54, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoiemma, G.; Tamburini, G.; Sanna, F.; Mori, N.; Marini, L. Landscape composition predicts the distribution of Philaenus spumarius, vector of Xylella fastidiosa, in olive groves. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 92, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefroid, M.; Morente, M.; Schartel, T.; Cornara, D.; Prucell, A.; Gallego, D.; Moreno, A.; Pereira, J.A.; Fereres, A. Climate tolerances of Philaenus spumarius should be considered in risk assessment of disease outbreaks related to Xylella fastidiosa. J. Pest Sci. 2022, 95, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilioli, G.; Simonetto, A.; Weber, I.D.; Gervasio, P.; Sperandio, G.; Bosco, D.; Bodino, N.; Dongiovanni, C.; Di Carolo, M.; Cavalieri, V.; et al. A model for predicting the phenology of Philaenus spumarius. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyaphongkul, J.; Pritchard, J.; Bale, J. Can tropical insects stand the heat? A case study with the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens (Stål). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdel-Rahman, A. A Review of Effects of Initial and Boundary Conditions on Turbulent Jets. WSEAS Trans. Fluid Mech. 2010, 5, 257–275. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, M.; Bätge, T.; Bodenschatz, E.; Wilczek, M.; Bagheri, G. Estimating the turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate from one-dimensional velocity measurements in time. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2024, 17, 627–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongiovanni, C.; Altamura, G.; Di Carolo, M.; Fumarola, G.; Saponari, M.; Cavalieri, V. Evaluation of Efficacy of Different Insecticides Against Philaenus spumarius L., Vector of Xylella fastidiosa in Olive Orchards in Southern Italy, 2015–2017. Arthropod Manag. Tests 2018, 43, tsy034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, C.; Cornara, D.; Minutillo, S.A.; Moreno, A.; Fereres, A. Feeding behaviour and mortality of Philaenus spumarius exposed to insecticides and their impact on Xylella fastidiosa transmission. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 4841–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EU). Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 485/2013 of 24 May 2013 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011, as regards the conditions of approval of the active substances clothianidin, thiamethoxam and imidacloprid, and prohibiting the use and sale of seeds treated with plant protection products containing those active substances. OJ 2013, 139, 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EU). Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/783 of 29 May 2018 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011 as regards the conditions of approval of the active substance imidacloprid. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, 132, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Blonda, P.; Tarantino, C.; Scortichini, M.; Maggi, S.; Tarantino, M.; Adamo, M. Satellite monitoring of bio-fertilizer restoration in olive groves affected by Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specification | Value |

|---|---|

| Dimension (L × W × H) | 901 mm × 300 mm × 204 mm |

| Weight | 178 kg |

| Fuel tank capacity | 3.6 L |

| Specification | Value |

|---|---|

| Heat output | 95 Kw |

| Flow rate | 6000 m3/h |

| Power intake/nominal voltage/nominal current | 700 W/230 V/4.5 A |

| LPG consumption | 7.7 kg/h |

| Gas pressure | 2 bar |

| Weight | 32 kg |

| Dimensions | 1140 mm × 470 mm × 610 mm |

| Test Area | Initial Nymphs’ Population Density (Nymphs/m2) | Nymphs’ Population Density (Nymphs/m2) After the Use of the Developed Machine | Mortality Rate [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 ± 1.07 | 2 ± 0.25 | 85.7 |

| 2 | 12 ± 1.07 | 2 ± 0.25 | 83.3 |

| 3 | 17 ± 1.07 | 3 ± 0.25 | 82.4 |

| 4 | 18 ± 1.07 | 3 ± 0.25 | 83.3 |

| 5 | 15 ± 1.07 | 2 ± 0.25 | 86.7 |

| Active Ingredient | Efficacy |

|---|---|

| deltamethrin | 100% after 1.5 h |

| acetamiprid | 100% after 2 h |

| pyrethrin | 12.5% after 4 h |

| kaolin, sulfoxaflor, and spinosad | No effects |

| pyrethroids pymetrozine and spirotetramat | 86.8% at 1 DAT 20% at 1 DAT |

| pyrethrin + piperonyl butoxide, | 95% at 1 DAT |

| azadirachtin and kaolin | 26% at 3 DAT |

| Method applied in this study | Efficacy |

| convective heating + aerodynamic force | 84.2% just after the use of the machine |

| Commercial Product | Number of Applications per Year | Price Per Liter [€ L−1] | Recommended Quantity [L ha−1] | Estimated Cost [€ ha−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dentamet® (zinc–copper–citric acid bio complex) | 6 | 20 | 3.9 | 468 |

| Epik SL (acetamiprid) | 5 | 40 | 1.5 | 300 |

| Decis Jet EC (deltamethrin) | 5 | 40 | 1.15 | 230 |

| Confidor 200 O-Teq (imidacloprid) | 5 | 30 | 1.15 | 173 |

| Karathe Zeon 1.5 CS (λ-cyhalothrin) | 5 | 30 | 2.5 | 375 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paciolla, F.; Farella, A.; Betrò, G.; Milella, A.; Pascuzzi, S. Development of an Innovative Mechanical–Aeraulic Device for Sustainable Vector Control of Nymphs of Philaenus spumarius. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2609. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242609

Paciolla F, Farella A, Betrò G, Milella A, Pascuzzi S. Development of an Innovative Mechanical–Aeraulic Device for Sustainable Vector Control of Nymphs of Philaenus spumarius. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2609. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242609

Chicago/Turabian StylePaciolla, Francesco, Alessia Farella, Gerardo Betrò, Annalisa Milella, and Simone Pascuzzi. 2025. "Development of an Innovative Mechanical–Aeraulic Device for Sustainable Vector Control of Nymphs of Philaenus spumarius" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2609. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242609

APA StylePaciolla, F., Farella, A., Betrò, G., Milella, A., & Pascuzzi, S. (2025). Development of an Innovative Mechanical–Aeraulic Device for Sustainable Vector Control of Nymphs of Philaenus spumarius. Agriculture, 15(24), 2609. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242609