Agricultural Drought Early Warning in Hunan Province Based on VPD Spatiotemporal Characteristics and BEAST Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Method

2.3.1. VPD Calculation

2.3.2. Bayesian Estimator of Abrupt Change, Seasonality, and Trend

3. Results

3.1. VPD Spatiotemporal Distribution

3.1.1. Spatial Distribution

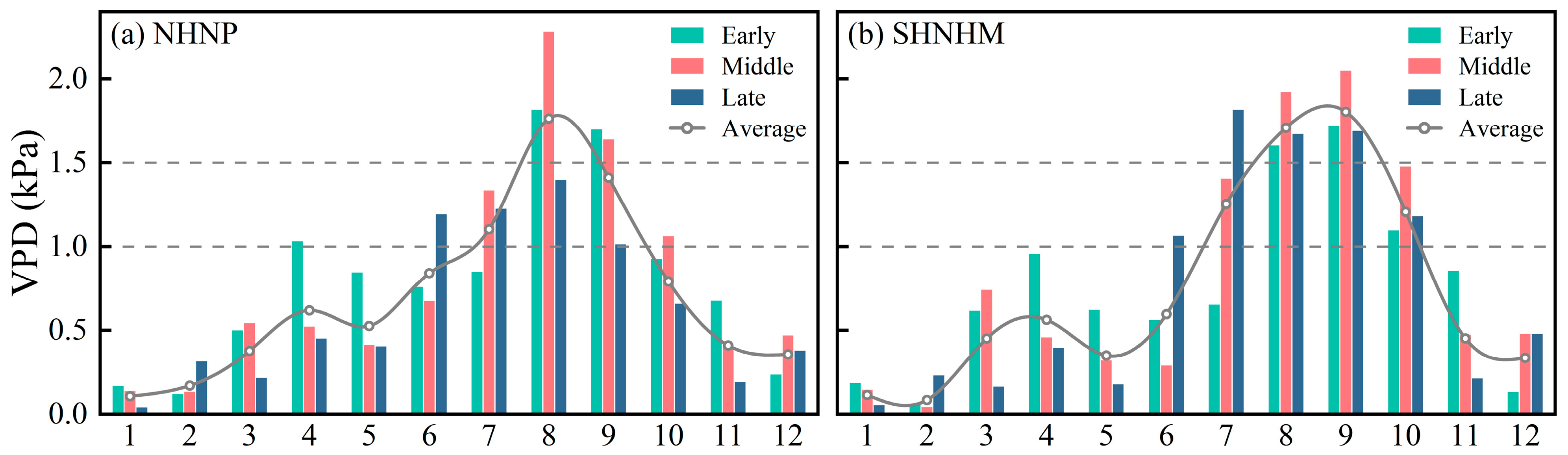

3.1.2. Temporal Distribution

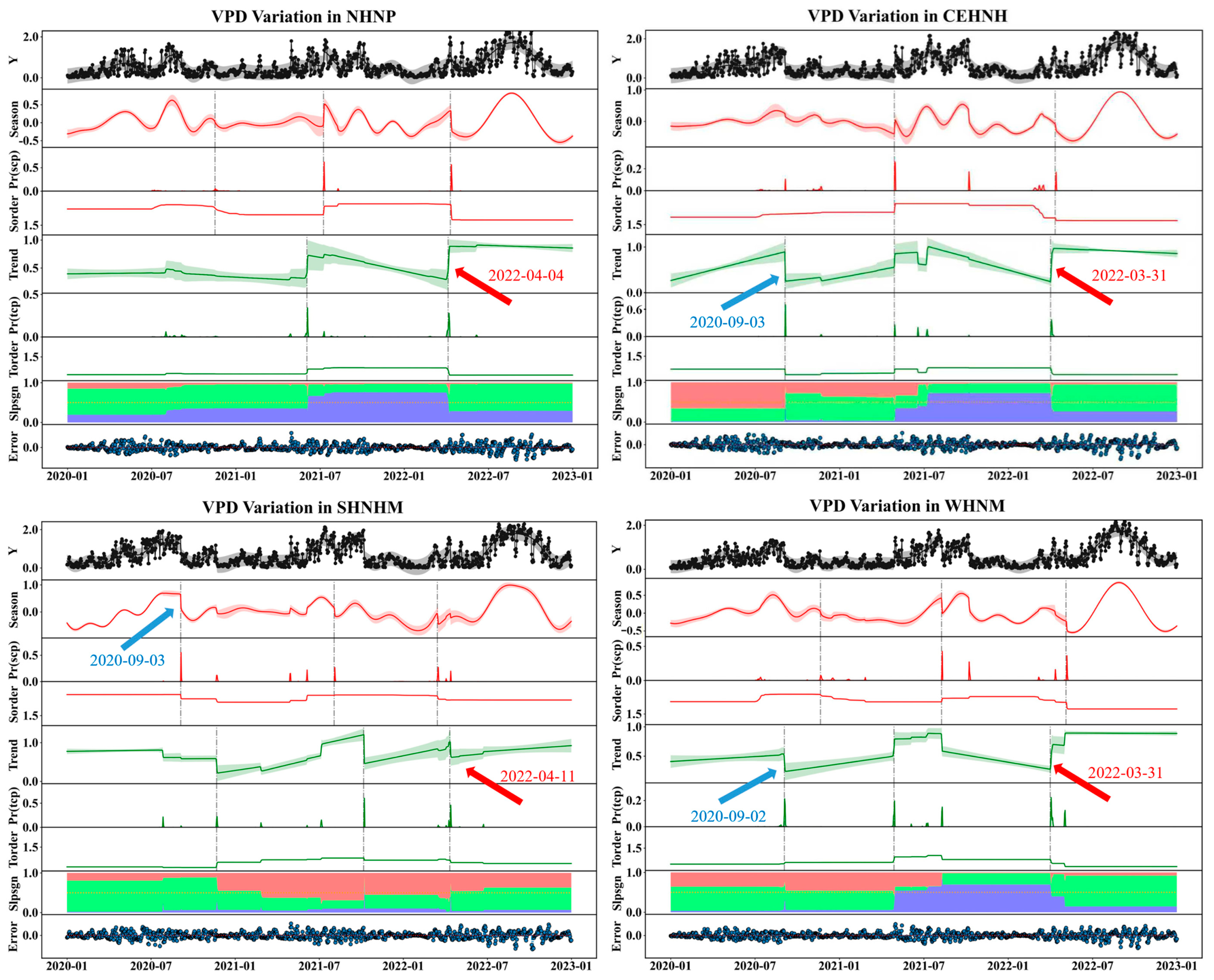

3.2. Detection of Abrupt Changes in Time Series

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact Factor of VPD Changes

4.2. Agricultural Risk Assessment of Extreme VPD Events

4.3. Mechanisms of the Occurrence of Abnormally High VPD in 2022

4.4. Drought Early Warning Based on VPD

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The VPD in Hunan Province exhibits a spatial distribution characteristic of “higher in the south/east and lower in the north/west.” In 2022, influenced by a compound high-temperature drought event, the annual average VPD rose to 0.72 ± 0.11 kPa. And summer and autumn are identified as high-risk periods for drought.

- (2)

- The BEAST algorithm accurately identified the change timing of VPD, such as the key change point during the early rice transplanting period in April 2022. The change points exhibit a spatiotemporal gradient characteristic of “from east to west and from south to north,” revealing the transmission path of drought risk and providing an important early warning window for irrigation scheduling by region and time period.

- (3)

- The changes in VPD are jointly regulated by temperature and humidity, with the being the dominant factor at the annual scale (contribution rate > 57%). At the seasonal scale, RH dominates in spring across the province, while summer shows regional differentiation—NHNP and WHNM are dominated by RH, whereas CEHNH and SHNHM are dominated by

- (4)

- In 2022, 92 meteorological stations in the province experienced extreme drought events (VPD > 1.5 kPa for 3 days). Considering the change characteristics of VPD in Hunan Province and the critical growth periods of double-crop rice, it is recommended to set VPD = 1 kPa as the agricultural drought warning threshold for the northern and southern regions to enhance drought risk prevention and control capabilities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, T.; Cheng, Y. Drought Area, Intensity and Frequency Changes in China under Climate Warming, 1961–2014. J. Arid Environ. 2021, 193, 104596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.R.; Skeg, J.; Buendia, E.C.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Zhai, P.; Slade, R.; Connors, S.; Diemen, S.; et al. (Eds.) Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ficklin, D.L.; Novick, K.A. Historic and Projected Changes in Vapor Pressure Deficit Suggest a Continental-Scale Drying of the United States Atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 2061–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Zuo, Z.; Lin, Z.; You, Q.; Wang, H. The Decadal Abrupt Change in the Global Land Vapor Pressure Deficit. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2023, 66, 1521–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Way, D.A.; Sadok, W. Systemic Effects of Rising Atmospheric Vapor Pressure Deficit on Plant Physiology and Productivity. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1704–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, G.; Chai, Y.; Miao, L.; Fiifi Tawia Hagan, D.; Sun, S.; Huang, J.; Su, B.; Jiang, T.; Chen, T.; et al. Increasing Vapor Pressure Deficit Accelerates Land Drying. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625, 130062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.L.; Sinclair, T.R.; Allen, L.H. Transpiration Responses to Vapor Pressure Deficit in Well Watered ‘Slow-Wilting’ and Commercial Soybean. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabel, A.; Girardin, M.P.; Metsaranta, J.; Way, D.; Reich, P.B. Increasing Atmospheric Dryness Reduces Boreal Forest Tree Growth. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seager, R.; Hooks, A.; Williams, A.P.; Cook, B.; Nakamura, J.; Henderson, N. Climatology, Variability, and Trends in the U.S. Vapor Pressure Deficit, an Important Fire-Related Meteorological Quantity. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2015, 54, 1121–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, J.; Swann, A.L.S.; Kim, S.-H. Maize Yield under a Changing Climate: The Hidden Role of Vapor Pressure Deficit. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 279, 107692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, G.; Li, S.; Hagan, D.F.T.; Ullah, W. The Combined Effects of VPD and Soil Moisture on Historical Maize Yield and Prediction in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1117184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Brandt, M.; Abdi, A.M.; Fensholt, R. Globally Increasing Atmospheric Aridity Over the 21st Century. Earths Future 2022, 10, e2022EF003019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wu, L.; Zeng, W.; Xiao, X.; He, J. Analysis of Spatial-Temporal Trends and Causes of Vapor Pressure Deficit in China from 1961 to 2020. Atmos. Res. 2024, 299, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Li, Z.; Cheng, D. Temporal and Spatial Variation and Influencing Factors of Saturated Water Vapor Pressure Difference in the Hai River Basin. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Tan, Y.; Shen, T.; Schaefer, D.A.; Chen, H.; Zhou, S.; Xu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, G.; et al. Spatiotemporal Trends of Atmospheric Dryness during 1980–2021 in Yunnan, China. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1397028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Tu, X.; Zhou, L.; Singh, V.P.; Chen, X.; Lin, K. Mutual-Information of Meteorological-Soil and Spatial Propagation: Agricultural Drought Assessment Based on Network Science. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhang, L.; Xu, T.; Yang, S.; Guo, J.; Si, L.; Kang, R.; Kaufmann, H.J. An Integrated Drought Index (Vapor Pressure Deficit–Soil Moisture–Sun-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence Dryness Index, VMFDI) Based on Multisource Data and Its Applications in Agricultural Drought Management. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunan Provincial Bureau Statistics Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of Hunan Province in 2022. Available online: https://tjj.hunan.gov.cn/hntj/m/tjgb_1/202303/t20230323_29289710.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Long, Z.; Sun, G.; Huang, J.; Jiang, F.; Feng, Q.; Wu, Y. Characteristics and variations of soil fertility in cultivated land across different regions of Hunan Province in the past 40 years. Chin. J. Soil Fertil. 2024, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Jiang, Z.; Li, L. Anthropogenic Influence on the Record-Breaking Compound Hot and Dry Event in Summer 2022 in the Yangtze River Basin in China. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E1928–E1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. (Eds.) Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; FAO irrigation and drainage paper; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998; ISBN 978-92-5-104219-9.

- Zhao, K.; Wulder, M.A.; Hu, T.; Bright, R.; Wu, Q.; Qin, H.; Li, Y.; Toman, E.; Mallick, B.; Zhang, X.; et al. Detecting Change-Point, Trend, and Seasonality in Satellite Time Series Data to Track Abrupt Changes and Nonlinear Dynamics: A Bayesian Ensemble Algorithm. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 232, 111181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, G.H.; Montgomery, D.R.; Hallet, B. Orographic Precipitation and the Relief of Mountain Ranges. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2003, 108, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auler, A.C.; Cássaro, F.A.M.; da Silva, V.O.; Pires, L.F. Evidence That High Temperatures and Intermediate Relative Humidity Might Favor the Spread of COVID-19 in Tropical Climate: A Case Study for the Most Affected Brazilian Cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 139090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Qiu, B.; Miao, X.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Tian, X.; Zhao, S.; Guo, W. Shift of Soil Moisture-Temperature Coupling Exacerbated 2022 Compound Hot-Dry Event in Eastern China. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 014059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fu, J.; Tang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fang, X. Spatiotemporal Variations of Drought and the Related Mitigation Effects of Artificial Precipitation Enhancement in Hengyang-Shaoyang Drought Corridor, Hunan Province, China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Yu, R.; Zhang, J.; Drange, H.; Cassou, C.; Deser, C.; Hodson, D.L.R.; Sanchez-Gomez, E.; Li, J.; Keenlyside, N.; et al. Why the Western Pacific Subtropical High Has Extended Westward since the Late 1970s. J. Clim. 2009, 22, 2199–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S.; Xu, H.; Cai, W. Response of Remote Water Vapor Transport to Large Topographic Effects and the Multi-Scale System during the “7.20” Rainstorm Event in Henan Province, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1106990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Han, L.; Liu, Q.; Li, C.; Pan, Z.; Xu, K. Spatial and Temporal Changes in Wetland in Dongting Lake Basin of China under Long Time Series from 1990 to 2020. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, G.; Fu, Z.; Ciais, P.; Feng, X.; Li, J.; Fu, B. Compound Droughts Slow down the Greening of the Earth. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 3072–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Wu, S. Diverse Spatiotemporal Patterns of Vapor Pressure Deficit and Soil Moisture across China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 52, 101712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, X.; Li, X. Spatial Variations of Climate-Driven Trends of Water Vapor Pressure and Relative Humidity in Northwest China. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 2019, 55, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Hu, X.-X.; Ma, Q.-R.; Feng, T.-C.; Feng, G.-L.; Ma, D. The 2022 Record-Breaking High Temperature in China: Sub-Seasonal Stepwise Enhanced Characteristics, Possible Causes and Its Predictability. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2023, 14, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.-Z.; Gao, H.; Gao, R.; Ding, T. Extreme Characteristics and Causes of the Drought Event in the Whole Yangtze River Basin in the Midsummer of 2022. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2023, 14, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhou, T.; Wu, B.; Chen, X. Seasonal Prediction of the Record-Breaking Northward Shift of the Western Pacific Subtropical High in July 2021. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 40, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Chen, J.; She, D. Impacts and countermeasures of extreme drought in the Yangtze River Basin in 2022. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2022, 53, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chan, J.C.L. The East Asian Summer Monsoon: An Overview. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2005, 89, 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Response of Stomatal Conductance and Phytohormones of Leaves to Vapor Pressure Deficit in Some Species of Plants. Ph.D. Thesis, Shan Dong University, Jinan, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sadok, W.; Lopez, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Tamang, B.G.; Muehlbauer, G.J. Sheathing the Blade: Significant Contribution of Sheaths to Daytime and Nighttime Gas Exchange in a Grass Crop. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 1844–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, N.; Krarti, M. Review of Energy Efficiency in Controlled Environment Agriculture. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, T.; Jia, F.; Cai, W.; Wu, L.; Gan, B.; Jing, Z.; Li, S.; McPhaden, M.J. Increased Occurrences of Consecutive La Niña Events under Global Warming. Nature 2023, 619, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Guan, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, L. The Anomalously Strong and Persistent Western Pacific Subtropical High in Summer 2022 in Association with the Extreme Heatwaves in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 2025, 83, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Cai, W.; Huang, G.; Hu, K.; Ng, B.; Wang, G. Increased Variability of the Western Pacific Subtropical High under Greenhouse Warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2120335119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Climate Center China Climate Bulletin 2022. China Meteorological Administration, Beijing. Available online: https://www.cma.gov.cn/zfxxgk/gknr/qxbg/202303/t20230324_5396394.html (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Berg, A.; Findell, K.; Lintner, B.; Giannini, A.; Seneviratne, S.I.; van den Hurk, B.; Lorenz, R.; Pitman, A.; Hagemann, S.; Meier, A.; et al. Land–Atmosphere Feedbacks Amplify Aridity Increase over Land under Global Warming. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; König, M.; Carminati, A.; Abdalla, M.; Javaux, M.; Wankmüller, F.; Ahmed, M.A. Transpiration Response to Soil Drying and Vapor Pressure Deficit Is Soil Texture Specific. Plant Soil 2024, 500, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gudmundsson, L.; Hauser, M.; Qin, D.; Li, S.; Seneviratne, S.I. Soil Moisture Dominates Dryness Stress on Ecosystem Production Globally. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Li, X.; Tong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, X. Vegetation Dynamics Dominate the Energy Flux Partitioning across Typical Ecosystem in the Heihe River Basin: Observation with Numerical Modeling. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Sunaga, M.; Ito, M.; Yuchen, Q.; Matsushima, Y.; Sakoda, K.; Yamori, W. Minimizing VPD Fluctuations Maintains Higher Stomatal Conductance and Photosynthesis, Resulting in Improvement of Plant Growth in Lettuce. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 646144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, S.; Gao, W.; Li, S.; Chen, Q.; Jiao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Qu, Y.; Chen, Q. Rapidly Mining Candidate Cotton Drought Resistance Genes Based on Key Indicators of Drought Resistance. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region | Trend Change | Season Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Probability | Time | Probability | |

| NHNP | — | — | 2020-11-15 | 0.87887 |

| 2021-06-02 | 0.94418 | 2021-07-08 | 0.98530 | |

| 2022-04-04 | 0.98960 | 2022-04-09 | 1.00000 | |

| CEHNH | 2020-09-03 | 0.94763 | — | — |

| 2021-04-27 | 0.99843 | 2021-04-27 | 1.00000 | |

| 2022-03-31 | 0.99525 | 2022-04-11 | 1.00000 | |

| SHNHM | 2020-11-20 | 0.82282 | 2020-09-03 | 1.00000 |

| 2021-10-06 | 0.99848 | 2021-08-02 | 1.00000 | |

| 2022-04-11 | 0.98507 | 2022-03-15 | 0.99565 | |

| WHNM | 2020-09-02 | 0.99978 | 2020-11-19 | 1.00000 |

| 2021-04-27 | 0.99928 | 2021-08-08 | 1.00000 | |

| 2022-03-31 | 0.71002 | 2022-05-04 | 0.91597 | |

| Region | Annual | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHNP | (57.1) > RH (42.9) | RH (53.4) > (46.6) | RH (64.8) > (35.2) | (60.8) > RH (39.2) | (60.4) > RH (39.6) |

| CEHNH | (58.2) > RH (41.8) | RH (55.1) > (44.9) | (52.3) > RH (47.7) | (64.9) > RH (35.1) | (59.2) > RH (40.8) |

| SHNHM | (60.6) > RH (39.4) | RH (53.7) > (46.3) | (56.2) > RH (43.8) | (66.4) > RH (33.6) | (61.4) > RH (38.6) |

| WHNM | (57.5) > RH (42.5) | RH (50.4) > (49.6) | RH (62.1) > (37.9) | (58.7) > RH (41.3) | (56.7) > RH (43.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, W.; Liang, J.; Yang, L.; Zhou, B.; Meng, S.; Gu, W.; Zhou, T. Agricultural Drought Early Warning in Hunan Province Based on VPD Spatiotemporal Characteristics and BEAST Detection. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242581

Fu W, Liang J, Yang L, Zhou B, Meng S, Gu W, Zhou T. Agricultural Drought Early Warning in Hunan Province Based on VPD Spatiotemporal Characteristics and BEAST Detection. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242581

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Wenyan, Ji Liang, Lian Yang, Bi Zhou, Saiying Meng, Weibin Gu, and Ting Zhou. 2025. "Agricultural Drought Early Warning in Hunan Province Based on VPD Spatiotemporal Characteristics and BEAST Detection" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242581

APA StyleFu, W., Liang, J., Yang, L., Zhou, B., Meng, S., Gu, W., & Zhou, T. (2025). Agricultural Drought Early Warning in Hunan Province Based on VPD Spatiotemporal Characteristics and BEAST Detection. Agriculture, 15(24), 2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242581