Biochar Addition Effects on Rice Yield and Climate Change from Rice in the Rice–Wheat System: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Introduction of GWP and GHGI

2.4. Meta-Analysis

2.5. Publication Bias

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

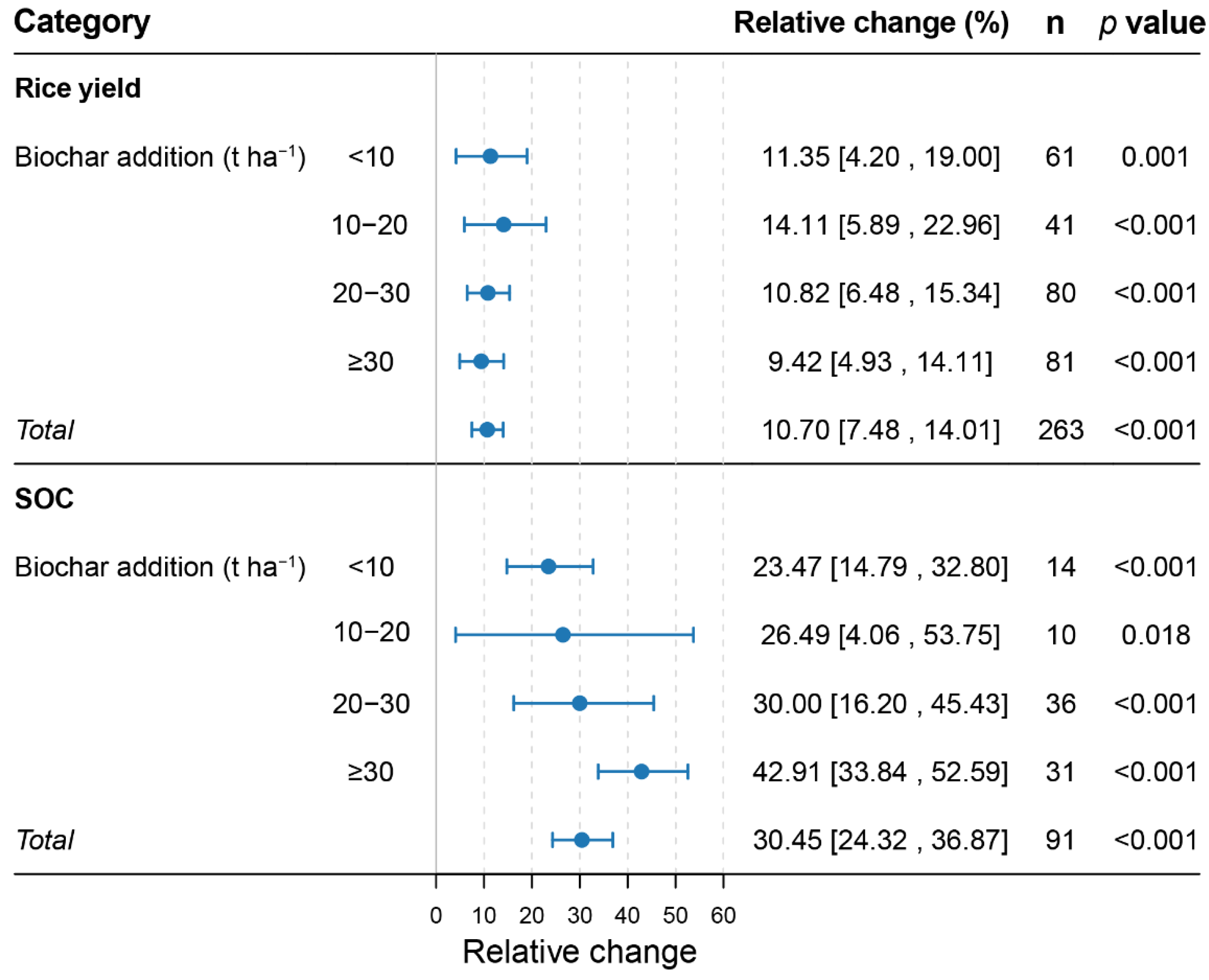

3.1. Response of Rice Yield and SOC to Using Biochar

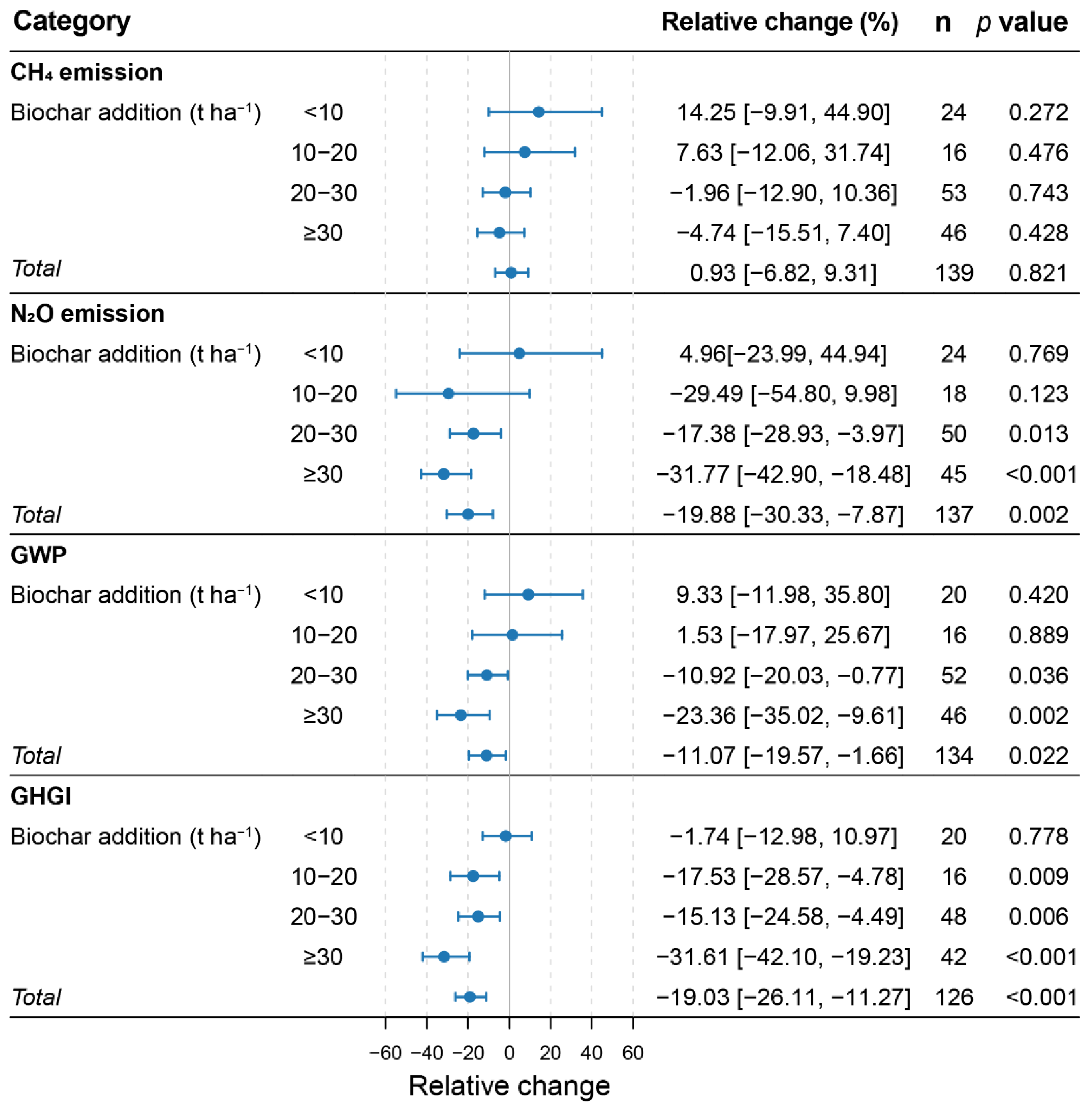

3.2. Response of GHG Emissions to Using Biochar

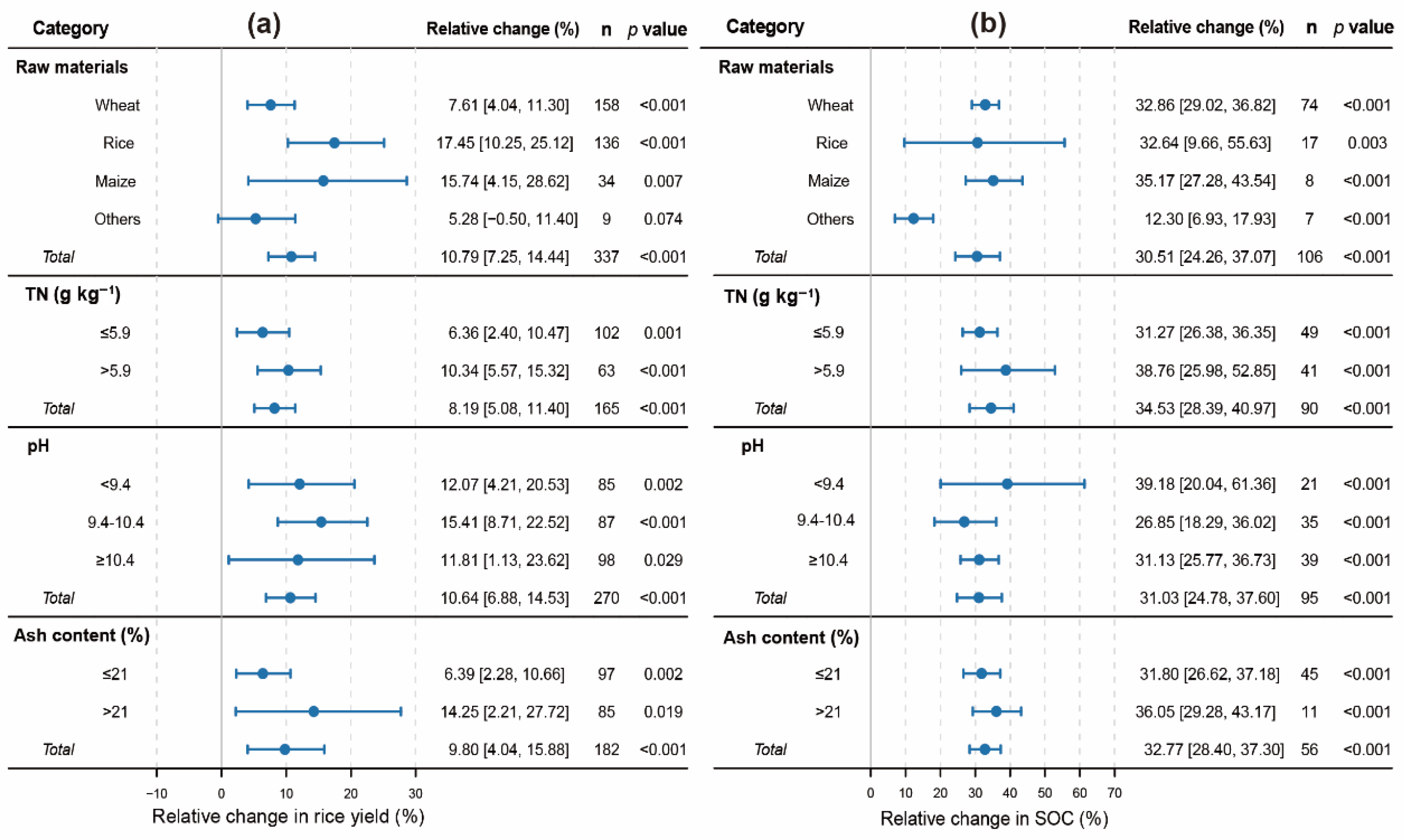

3.3. Effect of Biochar Properties on Yield and SOC

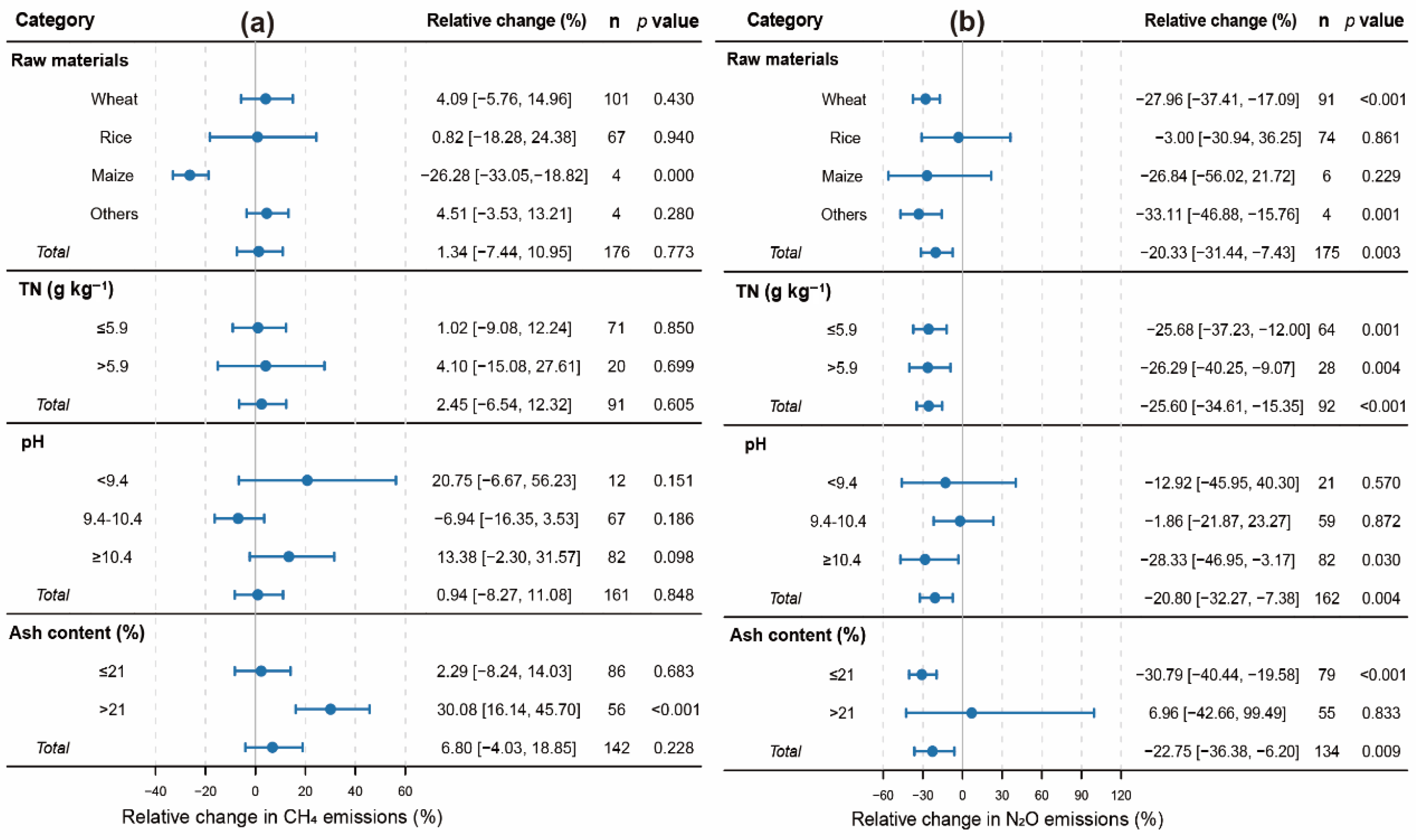

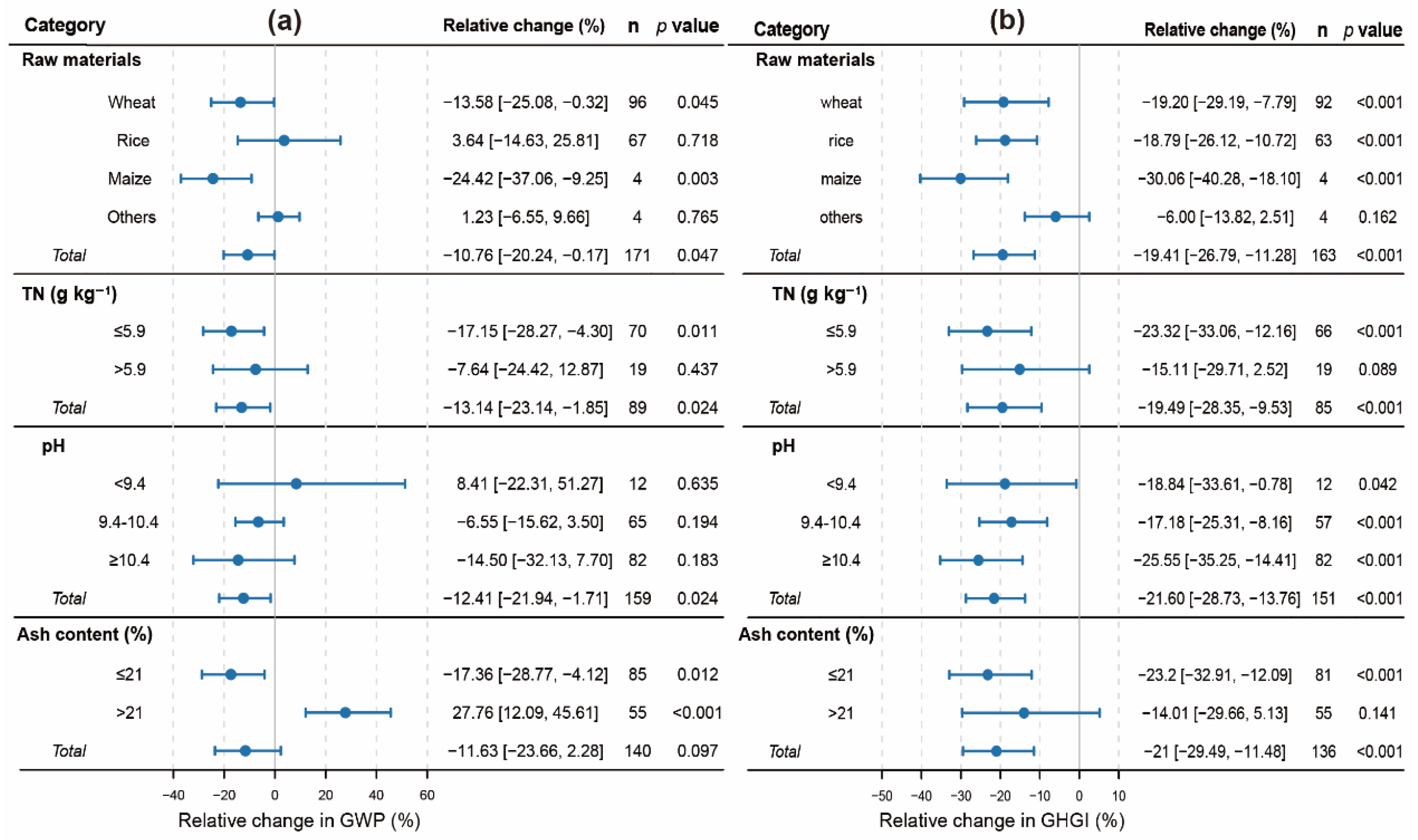

3.4. Effect of Biochar Properties on GHG Emissions

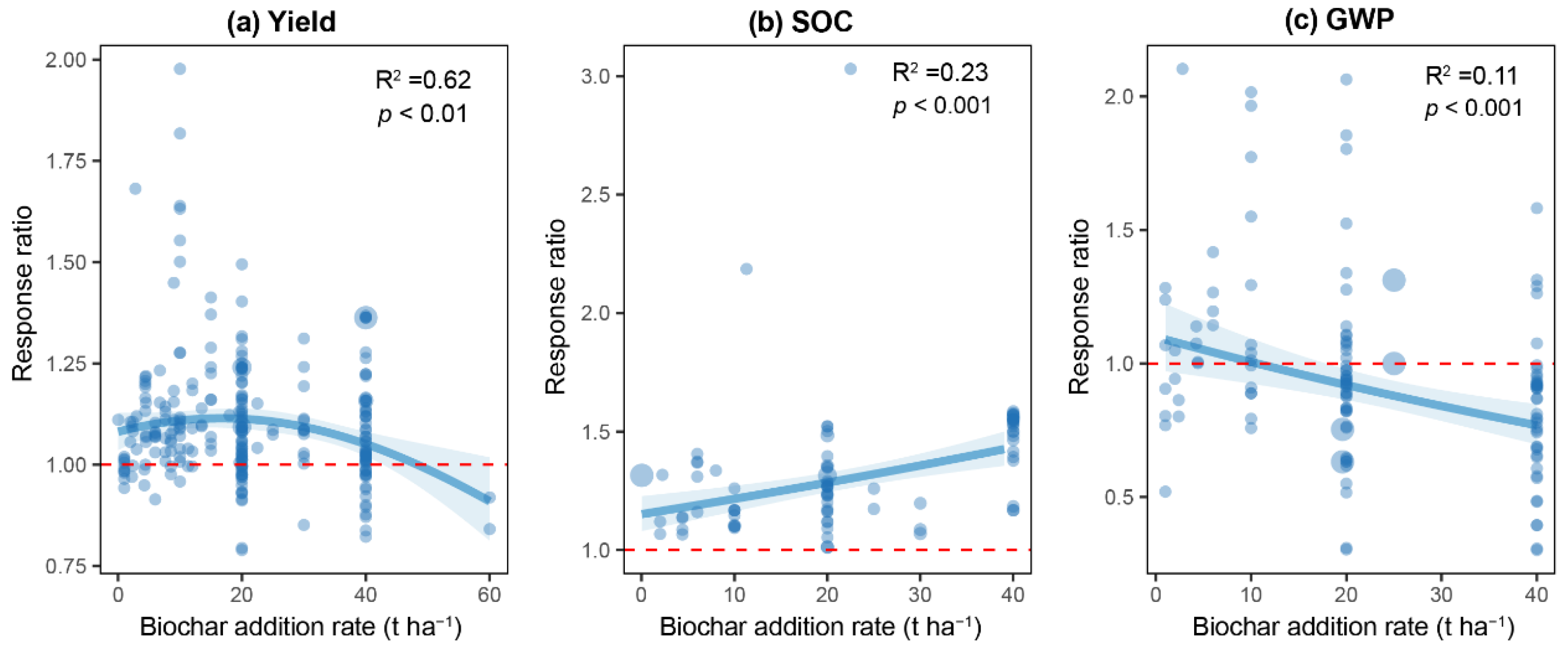

3.5. The Relationship Between Biochar Addition Rate and Yield and Climate Change

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanism of Rice Yield Increase

4.2. Improvement of Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration by Biochar

4.3. Mitigation of GHG Emissions by Biochar

4.4. Biochar Benefits Sustainable Agriculture and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tao, W.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Wen, C.; Gao, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Xu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Higher rice productivity and lower paddy nitrogen loss with optimized irrigation and fertilization practices in a rice-upland system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 374, 109176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ge, T.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Cheng, K.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Guggenberger, G.; et al. Rice paddy soils are a quantitatively important carbon store according to a global synthesis. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Hu, Q.; Tang, J.; Li, C.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, J.; Cao, M. Key influencing factors and technical system of carbon sequestration and emission reduction in rice production in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2022, 30, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021-The Physical Science Basis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Guo, C.; Xu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Chadwick, D.; Gao, X.; Zhou, F.; Lakshmanan, P.; Wang, X.; Guan, X.; et al. Co-benefits for net carbon emissions and rice yields through improved management of organic nitrogen and water. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Zhu, X.; Huang, S.; Linquist, B.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wassmann, R.; Minamikawa, K.; Martinez-Eixarch, M.; Yan, X.; Zhou, F.; et al. Greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation in rice agriculture. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 716–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lian, Z.; Ouyang, W.; Yan, L.; Liu, H.; Hao, F. Potential of optimizing irrigation and fertilization management for sustainable rice production in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 432, 139738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpel, C.; Lehmann, J.; Chabbi, A. ‘4 per 1000’initiative will boost soil carbon for climate and food security. Nature 2018, 553, 7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Chen, W.; Lu, B.; Wang, S.; Xiao, L.; Liu, B.; Yang, H.; Huang, C.-L.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Climate mitigation potential of sustainable biochar production in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 175, 113145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, D.; Amonette, J.E.; Street-Perrott, F.A.; Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Sustainable biochar to mitigate global climate change. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, T.; Mahmoud, A.; Li, J.; Zhu, R.; Jiao, X.; Jing, P. A quantitative review of the effects of biochar application on rice yield and nitrogen use efficiency in paddy fields: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 830, 154792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Cui, L.; Pan, G.; Li, L.; Hussain, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J.; Crowley, D. Effect of biochar amendment on yield and methane and nitrous oxide emissions from a rice paddy from Tai Lake plain, China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 139, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Zhou, S. Long term comparison of GHG emissions and crop yields in response to direct straw or biochar incorporation in rice-wheat rotation systems: A 10-year field observation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 374, 109188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Chi, Z.; Zheng, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J.; Cheng, K.; Bian, R.; Pan, G. Biochar provided limited benefits for rice yield and greenhouse gas mitigation six years following an amendment in a fertile rice paddy. Catena 2019, 179, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, S. Optimal Straw Retention Strategies for Low-Carbon Rice Production: 5 Year Results of an In Situ Trial in Eastern China. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, H.; Gao, J.; Wan, X.; Yan, B.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, G.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W. Effects of biochar application methods on greenhouse gas emission and nitrogen use efficiency in paddy fields. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 169809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhao, Z.; Ding, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, S.; Shao, Q.; Liu, X.; Cheng, K.; Bian, R.; Zheng, J.; et al. Crop Residue Biochar Rather Than Manure and Straw Return Provided Short Term Synergism Among Grain Production, Carbon Sequestration, and Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction in a Paddy Under Rice-Wheat Rotation. Food Energy Secur. 2024, 13, e70009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, T.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Dai, W.; Chi, D.; Xia, G. Biochar decreased N loss from paddy ecosystem under alternate wetting and drying in the Lower Liaohe River Plain, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 305, 109108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ren, T.; Yang, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Lu, J. Biochar return in the rice season and straw mulching in the oilseed rape season achieve high nitrogen fertilizer use efficiency and low greenhouse gas emissions in paddy-upland rotations. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 148, 126869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Cao, L.; Yang, Y.; Ti, C.; Liu, Y.; Smith, P.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Lehmann, J.; Lal, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; et al. Integrated biochar solutions can achieve carbon-neutral staple crop production. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y.; Li, B.; Xiong, Z. Biochar amendment reduced greenhouse gas intensities in the rice-wheat rotation system: Six-year field observation and meta-analysis. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 278, 107625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, D.; Wu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Yang, S. Assessment of the straw and biochar application on greenhouse gas emissions and yield in paddy fields under intermittent and controlled irrigation patterns. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 359, 108745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, L.; Li, M.; Du, Z.; Zhou, G.; Shao, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Hosseini Bai, S.; et al. Effects of biochar application on soil greenhouse gas fluxes: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2017, 9, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, L.; Huang, W.; Zhao, L.; Cao, X. Biochar-amended soil can further sorb atmospheric CO2 for more carbon sequestration. Commun. Earth. Environ. 2025, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xue, L.; Liu, J.; Xia, L.; Jia, P.; Feng, Y.; Hao, X.; Zhao, X. Biochar application reduced carbon footprint of maize production in the saline−alkali soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 368, 109001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinger, A.; Muller, A.; Haeni, M.; Skinner, C.; Fliessbach, A.; Buchmann, N.; Mader, P.; Stolze, M.; Smith, P.; Scialabba Nel, H.; et al. Enhanced top soil carbon stocks under organic farming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18226–18231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Wei, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Zhang, F. Conservation tillage or plastic film mulching? A comprehensive global meta-analysis based on maize yield and nitrogen use efficiency. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Agathokleous, E.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, H.; Huo, Z. Nitrogen and organic matter managements improve rice yield and affect greenhouse gas emissions in China’s rice-wheat system. Field Crops Res. 2025, 326, 109838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Cao, H.; Qi, C.; Hu, Q.; Liang, J.; Li, Z. Straw management in paddy fields can reduce greenhouse gas emissions: A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2024, 306, 109218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Luo, N.; Liu, J.; Fang, Y.; Qi, Z.; Li, S.; Gao, Z.; Feng, Y.; Chu, Q.; Dai, H. Data-driven strategies to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions intensity while sustaining global rice production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2026, 224, 108547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Tian, F.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, F. Fertilization enhances microbial-driven N2O emissions while film mulching mitigates fertilization-driven emissions. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 171, 127804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, K.; Liao, P.; Xu, Q. Effect of agricultural management practices on rice yield and greenhouse gas emissions in the rice–wheat rotation system in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 916, 170307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Subbotina, I.; Chen, H.; Bogomolova, I.; Xu, X. Black carbon decomposition and incorporation into soil microbial biomass estimated by 14C labeling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, X.; Chai, N.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, F.-M. Biochar effects on crop yield variability. Field Crops Res. 2024, 316, 109518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Jiu, A.; Kan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Yang, H.; Li, F.-M. Deep tillage combined with straw biochar return increases rice yield by improving nitrogen availability and root distribution in the subsoil. Field Crops Res. 2024, 315, 109481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, S.; Sun, H.; Lu, F.; He, P. Three-year rice grain yield responses to coastal mudflat soil properties amended with straw biochar. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 239, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Song, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yan, X.; Gunina, A.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Xiong, Z. Effects of six-year biochar amendment on soil aggregation, crop growth, and nitrogen and phosphorus use efficiencies in a rice-wheat rotation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, X.; Pan, G.; Zheng, J.; Chi, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J. Changes in soil properties, yield and trace gas emission from a paddy after biochar amendment in two consecutive rice growing cycles. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2012, 45, 4844–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Q.; Tang, L.; Chi, W.; Waqas, M.; Wu, W. The implication from six years of field experiment: The aging process induced lower rice production even with a high amount of biochar application. Biochar 2023, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, B.; Shen, J.; Zhu, X.; Yi, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. Contrasting effects of straw and straw-derived biochar applications on soil carbon accumulation and nitrogen use efficiency in double-rice cropping systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 311, 107286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriphirom, P.; Rossopa, B. Assessment of greenhouse gas mitigation from rice cultivation using alternate wetting and drying and rice straw biochar in Thailand. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 290, 108586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Bian, R.; Xia, X.; Cheng, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Legacy of soil health improvement with carbon increase following one time amendment of biochar in a paddy soil–A rice farm trial. Geoderma 2020, 376, 114567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Li, G.; Zhao, X.; Lin, Q.; Wang, X. Biochar application significantly increases soil organic carbon under conservation tillage: An 11-year field experiment. Biochar 2023, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.S.; Mack, R.; Castillo, X.; Kaiser, M.; Joergensen, R.G. Microbial biomass, fungal and bacterial residues, and their relationships to the soil organic matter C/N/P/S ratios. Geoderma 2016, 271, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, L.; Ma, J.; Ma, J.; Ye, J.; Yu, Q.; Zou, P.; Sun, W.; Lin, H.; Wang, F.; et al. Long-term successive biochar application increases plant lignin and microbial necromass accumulation but decreases their contributions to soil organic carbon in rice–wheat cropping system. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2024, 16, e13137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.; Bromm, T.; Glaser, B. Soil organic carbon sequestration after biochar application: A global meta-analysis. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, H.; Gao, J.; Feng, Y.; Yan, B.; Li, K.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, W. Effects of nitrogen co-application by different biochar materials on rice production potential and greenhouse gas emissions in paddy fields in northern China. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, S.; Shan, J.; Xia, Y.; Lin, J.; Yan, X. A 2-year study on the effect of biochar on methane and nitrous oxide emissions in an intensive rice–wheat cropping system. Biochar 2019, 1, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Yang, S.; Pang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Sun, X.; Qi, S.; Yu, W. Biochar improved soil health and mitigated greenhouse gas emission from controlled irrigation paddy field: Insights into microbial diversity. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Han, J.; Liu, Z.; Xia, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Bian, R.; Cheng, K.; Zheng, J.; et al. Biochar compound fertilizer increases nitrogen productivity and economic benefits but decreases carbon emission of maize production. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 241, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enebe, M.C.; Ray, R.L.; Griffin, R.W. The impacts of biochar on carbon sequestration, soil processes, and microbial communities: A review. Biochar 2025, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Hou, R.; Fu, Q.; Li, T.; Wang, J.; Su, Z.; Shen, W.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, M. Modified biochar reduces the greenhouse gas emission intensity and enhances the net ecosystem economic budget in black soil soybean fields. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 237, 105978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, K.; Wei, H. Biochar Addition Effects on Rice Yield and Climate Change from Rice in the Rice–Wheat System: A Meta-Analysis. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2537. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242537

Zhang L, Zhang F, Zhang K, Wei H. Biochar Addition Effects on Rice Yield and Climate Change from Rice in the Rice–Wheat System: A Meta-Analysis. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2537. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242537

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Li, Feng Zhang, Kaiping Zhang, and Huihui Wei. 2025. "Biochar Addition Effects on Rice Yield and Climate Change from Rice in the Rice–Wheat System: A Meta-Analysis" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2537. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242537

APA StyleZhang, L., Zhang, F., Zhang, K., & Wei, H. (2025). Biochar Addition Effects on Rice Yield and Climate Change from Rice in the Rice–Wheat System: A Meta-Analysis. Agriculture, 15(24), 2537. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242537