Effect of Airflow Settings of an Orchard Sprayer with Two Individually Controlled Fans on Spray Deposition in Apple Trees and Off-Target Drift

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sprayer

2.1.1. Design and Construction

2.1.2. Fan Speed and Airflow Settings

- S—Symmetrical emission: L/R = 100%/100%(representing the conventional, reference technique);

- C—Compensating crosswind: L/R = 30%/100%(compensating for the effects of crosswinds and reducing spray loss);

- O—One-sided emission: L/R = 0%/100%(representing spray drift-reducing scenario).

2.2. Site and Conditions

2.3. Conduct of Experiments

- Q—spray volume rate [L ha−1];

- CH—canopy height [m];

- CD—mid-height canopy diameter across row [m];

- R—row spacing [m];

- k (here: 0.033)—efficacious unit volume rate [L m−3TRV].

2.3.1. In-Canopy Deposit—Treatment Quality

- Cw—concentration of tracer in wash solution (fluorimeter reading) [ng mL−1];

- Vw—volume of wash water used [mL];

- Cs—concentration of tracer in spray liquid [%(w/v)];

- Va—spray application rate [L ha−1];

- Ac—collector surface area [cm2].

2.3.2. Ground Deposit in Orchard—Spray Loss to Soil

2.3.3. Off-Target Deposition Drift

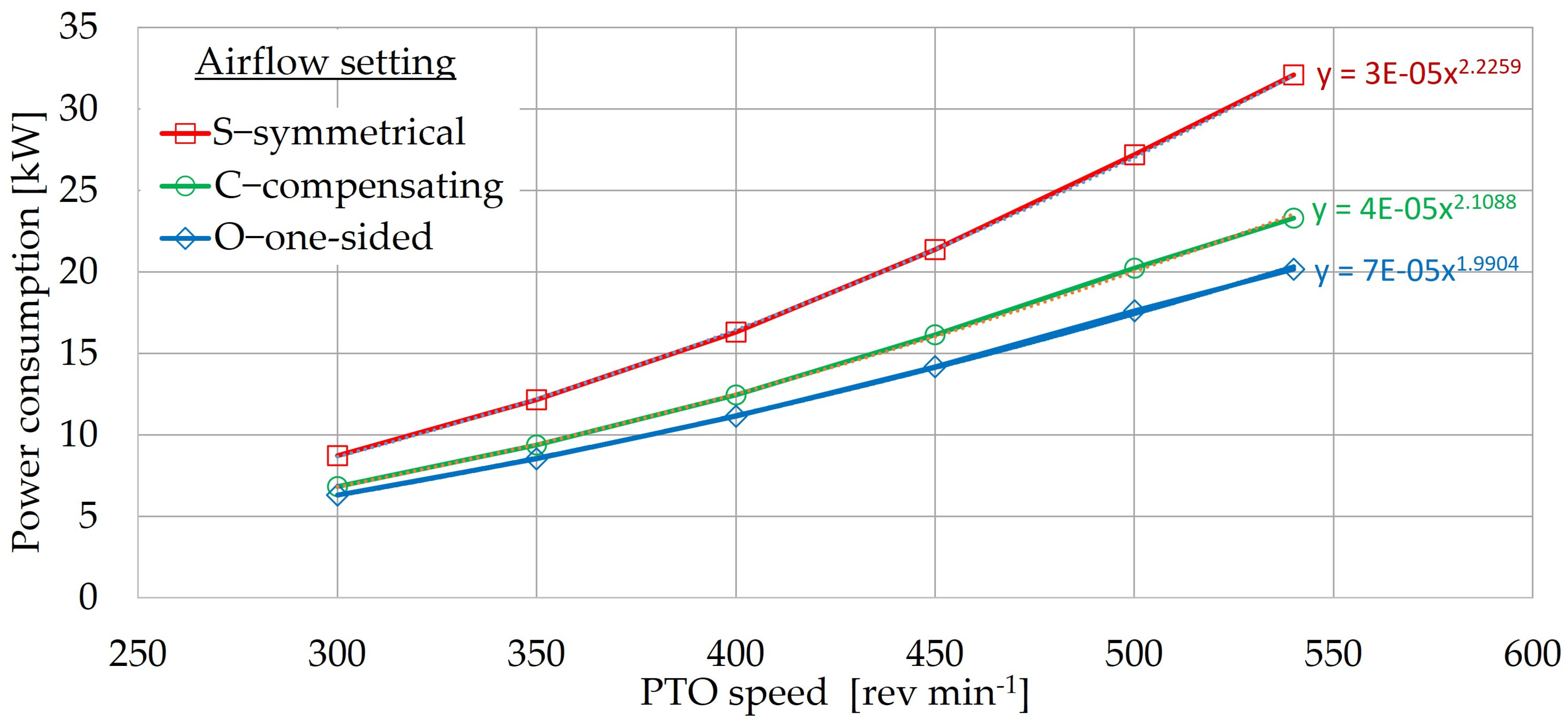

2.3.4. Power Consumption—CO2 Emission

- Scenario S: Pump (0.6 MPa) + LEFT fan 100% + RIGHT fan 100%;

- Scenario C: Pump (0.6 MPa) + LEFT fan 30% + RIGHT fan 100%;

- Scenario O: Pump (0.6 MPa) + LEFT fan 0% + RIGHT fan 100%.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. In-Canopy Spray Deposition

- S—Symmetrical (100%/100%);

- C—Compensatory (30%/100%);

- O—One-sided (0%/100%).

3.2. Ground Deposit in Orchard—Spray Loss to Soil

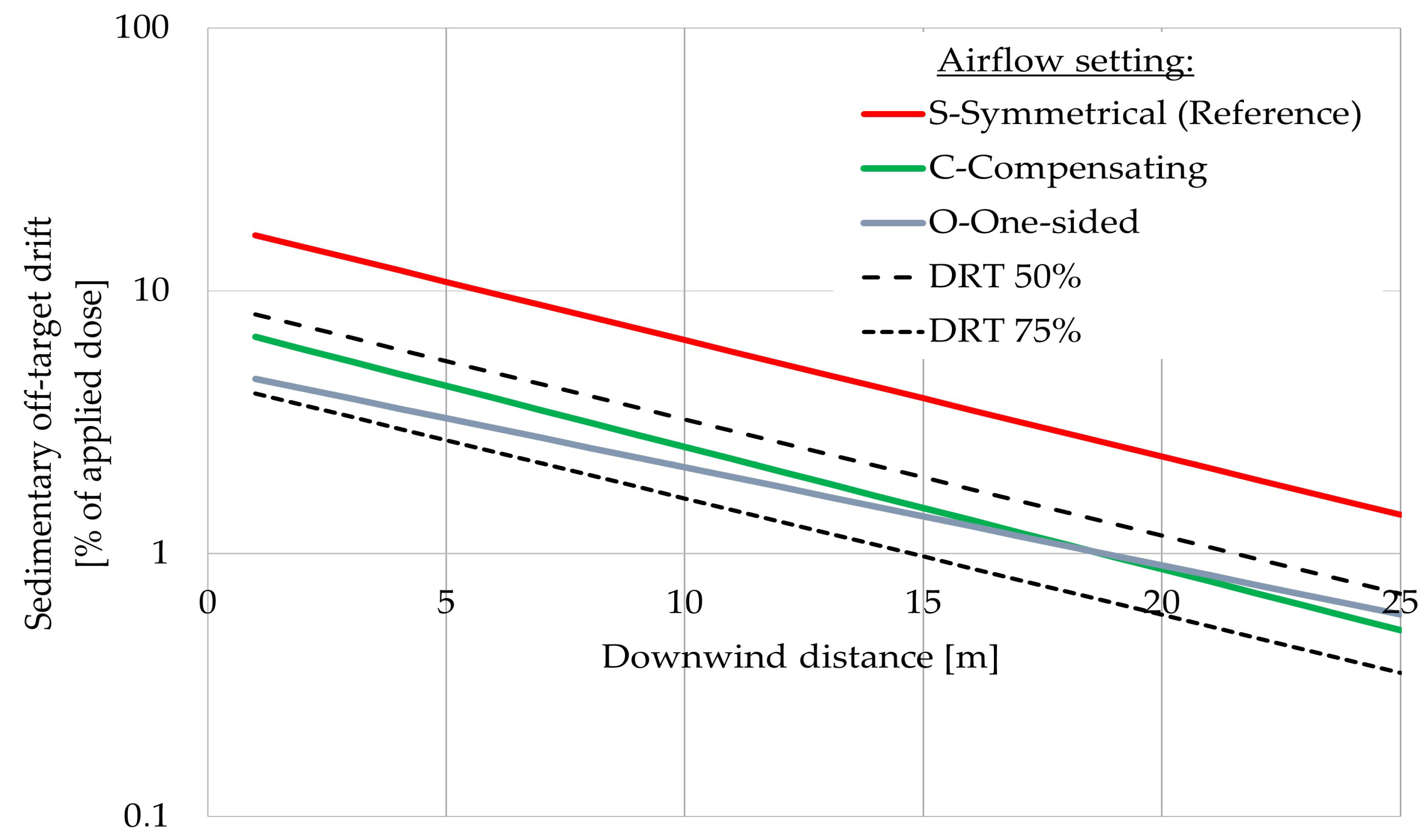

3.3. Off-Target Deposition Drift and Drift-Reduction Rate

- DRP(C,O)—drift-reduction potential for the evaluated scenario C or O [%],

- DPS—drift potential within the measurement range for the reference scenario S [%],

- DP(C,O)—drift potential within the measurement range for the evaluated scenario C or O [% of applied dose].

3.4. Power Consumption, Fuel Consumption, and CO2 Emission

- Volumetric energy density of diesel (heating value, i.e., the amount of thermal energy in one liter of diesel): W = 10.55 kWh L−1 [40];

- Efficiency of a heavy-duty diesel tractor engine (i.e., the ratio of effective mechanical energy produced by the engine to the thermal energy of the diesel fuel): η = 35% [41];

- Amount of CO2 produced from diesel combustion: G = 3.15 kg CO2 kg−1 fuel [42];

- Density of diesel: ρ = 0.838 g cm−3.

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Considerations

4.2. Penetration and Vertical Distribution of Spray Within the Canopy

4.3. In-Canopy Deposition Levels in Context of Literature Thresholds

4.4. Spray Losses to Soil and Implications for Environmental Risk

4.5. Off-Target Drift and Drift-Reduction Potential

4.6. Balancing Drift Reduction and Biological Efficacy

4.7. Energy Use, Fuel Consumption, and CO2 Emissions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Jia, W.; Ou, M.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Z. A Review on the Evolution of Air-Assisted Spraying in Orchards and the Associated Leaf Motion During Spraying. Agriculture 2025, 15, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jumaili, A.; Salyani, M. Variation in Deposition of an Air-Assisted Sprayer in Open Field Due to Wind Conditions. Trans. ASABE 2014, 57, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.V.; Walklate, P.J.; Murray, R.A.; Richardson, G.M. Spray deposits and losses in different sized apple trees from an axial fan orchard sprayer: 1. Effects of spray liquid flow rate. Crop Prot. 2001, 20, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endalew, A.M.; Debaer, C.; Rutten, N.; Vercammen, J.; Delele, M.A.; Ramon, H.; Nicolaï, B.M.; Verboven, P. Modelling pesticide flow and deposition from air-assisted orchard spraying in orchards: A new integrated CFD approach. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Zhao, S.Q.; Ding, W.M.; Sun, C.D.; Lu, J.; Li, Y.N.; Gu, J. Effects of fan speed on spray deposition and drift for targeting air-assisted sprayer in pear orchard. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2016, 9, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.W.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, H. CFD simulation of pesticide spray from air-assisted sprayers in an apple orchard: Tree deposition and off-target losses. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 175, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcera, C.; Moltó, E.; Izquierdo, H.; Balsari, P.; Marucco, P.; Grella, M.; Gioelli, F.; Chueca, P. Effect of the Airblast Settings on the Vertical Spray Profile: Imple-mentation on an On-Line Decision Aid for Citrus Treatments. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grella, M.; Gioelli, F.; Marucco, P.; Mozzanini, E.; Caffini, A.; Nuyttens, D.; Zwertvaegher, I.; Fountas, S.; Athanasakos, L.; Mylonas, N.; et al. Exploring variable air flow rate as a function of leaf area index for optimal spray deposition in trellised vineyards. International Advances in Pesticide Application. Asp. Appl. Biol. 2022, 147, 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, K.; Jin, H. Impact of airflow-assisted spraying technology on droplet drift: A solution for reducing pesticide drift under multidirectional strong wind conditions. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 3312–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; He, M.; Cui, H.; Lin, P.; Chen, Y.; Ling, G.; Huang, G.; Fu, H. Characterizing Droplet Retention in Fruit Tree Canopies for Air-Assisted Spraying. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Li, R.; Xue, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Chang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Dou, Q. Research Status, Methods and Prospects of Air-Assisted Spray Technology. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Yang, S.; Zou, W.; Zhai, C. Deposition Characteristics of Air-Assisted Sprayer Based on Canopy Volume and Leaf Area of Orchard Trees. Plants 2025, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derksen, R.C.; Krause, C.R.; Fox, R.D.; Brazee, R.D.; Zondag, R. Effect of Application Variables on Spray Deposition, Coverage, and Ground Losses in Nursery Tree Applications. J. Environ. Hortic. 2006, 24, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, H.; Qiu, W.; Lv, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, G. Model construction and validation of airflow velocity attenuation through pear tree canopies. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1026503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Ran, X.; Zhong, Y.; Jin, Y.; Song, J. Effect of airflow angle on abaxial surface deposition in air-assisted spraying. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 4, 1211104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyani, M.; Pai, N.; Sweeb, R.D. On-the-go changing of sprayer airflow based on tree foliage density. In Proceedings of the A: 9th Workshop on Sustainable Plant Protection Techniques in Fruit Growing (SuProFruit), Alnarp, Sweden, 12–14 September 2007; pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, N.; Salyani, M.; Sweeb, R.D. Regulating Airflow of Orchard Airblast Sprayer Based on Tree Foliage Density. Trans. ASABE 2009, 52, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, A.J. The Development of a Precision Canopy Sprayer for Orchards and Vineyards. In Proceedings of the 8th Fruit, Nut and Vegetable Production Engineering Symposium, Concepcion, Chile, 5–9 January 2009; pp. 485–493. [Google Scholar]

- Landers, A.J. Developments towards an automatic precision sprayer for fruit crop canopies. In Proceedings of the 2010 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 20–23 June 2010; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2010; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doruchowski, G.; Świechowski, W.; Hołownicki, R.; Godyń, A. Environmentally-Dependent Application System (EDAS) for safer spray application in fruit growing. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotech. 2009, 84, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsari, P.; Marucco, P.; Tamagnone, M. A crop identification system (CIS) to optimise pesticide applications in orchards. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotech. 2009, 84, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doruchowski, G.; Balsari, P.; Van de Zande, J. Development of a crop adapted spray application system for sustainable plant protection in fruit growing. Acta Hortic. 2009, 824, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Zhai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Gu, C.; Yang, S. Research on decoupled air speed and air volume adjustment methods for air-assisted spraying in orchards. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1250773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Dou, H.; Zhai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, W.; Hao, J. Design and Experiment of Orchard Air-Assisted Sprayer with Airflow Graded Control. Agronomy 2025, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hołownicki, R.; Doruchowski, G.; Świechowski, W.; Godyń, A.; Konopacki, P. Variable air assistance system for orchard sprayers: Concept, design and preliminary testing. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 163, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, R.; Fonte, A.; Grella, M.; Garcera, C.; Chueca, P. Blade pitch and air-outlet width effects on the airflow generated by an airblast sprayer with wireless remote-controlled axial fan. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 190, 106428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenneker, M.; Nieuwenhuizen, A.T.; Zande, V.D.J.C.; Balsari, P.; Doruchowski, G.; Marucco, P. Advanced drift reduction in orchard spraying. International Advances in Pesticide Application. Asp. Appl. Biol. 2012, 114, 421–427. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Yu, S.; Wang, P.; Liu, H.; Yang, X. Anti-Drift Technology Progress of Plant Protection Applied to Orchards: A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.; Walklate, P.; Murray, R.; Richardson, G. Spray deposits and losses in different sized apple trees from an axial fan orchard sprayer: 3. Effects of air volumetric flow rate. Crop Prot. 2003, 22, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, L.; Campos, J.; Salas, B.; Fabregas, F.X.; Zhu, H.; Gil, E. Advanced spraying systems to improve pesticide saving and reduce spray drift for apple orchards. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1526–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenneker, M.; Van de Zande, J.C. Spray drift reducing effects of natural windbreaks in orchard spraying. International Advances in Pesticide Application. Asp. Appl. Biol. 2008, 84, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Grella, M.; Gallart, M.; Marucco, P.; Balsari, P.; Gil, E. Ground Deposition and Airborne Spray Drift Assessment in Vineyard and Orchard: The Influence of Environmental Variables and Sprayer Settings. Sustainability 2017, 9, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, R.; Zhu, H.; Ozkan, E.; Falchieri, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z. Reducing ground and airborne drift losses in young apple orchards with PWM-controlled spray system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 189, 106389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dong, X.; Jia, W.; Ou, M.; Yu, P.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y.; Lu, F. Influence of Wind Speed on the Motion Characteristics of Peach Leaves (Prunus persica). Agriculture 2024, 14, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duga, A.T.; Dekeyser, D.; Ruysen, K.; Bylemans, D.; Nuyttens, D.; Nicolai, B.M.; Verboven, P. Numerical Analysis of the Effects of Wind and Sprayer Type on Spray Distribution in Different Orchard Training Systems. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2015, 157, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failla, S.; Bisaglia, C.; Schillaci, G.; Longo, D.; Romano, E. Sprayer Axial Fan Layout Affecting Energy Consumption and Carbon Emissions. Resources 2020, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcera, C.; Doruchowski, G.; Chueca, P. Harmonization of plant protection products dose expression and dose adjustment for high growing 3D crops: A review. Crop Prot. 2021, 140, 105417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 22866:2005; Equipment for Crop Protection—Methods for Field Measurement of Spray Drift. International Organization for Standardization: London, UK, 2005.

- Nuyttens, D. Drift from Field Crop Sprayers: The Influence of Spray Application Technology Determined Using Indirect and Direct Drift Assessment Means. Ph.D. Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven-Faculteit Bio-ingenieurswetenschappen, Leuven, Belgium, 2007; p. 772, ISBN 978-90-8826-039-1. [Google Scholar]

- Speight, J.G. 2-Production, properties and environmental impact of hydrocarbon fuel conversion. In Advances in Clean Hydrocarbon Fuel Processing; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Khan, M.R., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2011; pp. 54–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvengadam, A.; Pradhan, S.; Thiruvengadam, P.; Besch, M.; Carder, D.; Delgado, O. Heavy-Duty Vehicle Diesel Engine Efficiency Evaluation and Energy Audit; Final Report; Center for Alternative Fuels, Engines & Emissions-West Virginia University: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2014; p. 61. Available online: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/HDV_engine-efficiency-eval_WVU-rpt_oct2014.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Baráth, B.; Jagicza, M.; Sütheö, G.; Tóth, G.L. Examination of the Load’s Effect on Fuel Consumption and CO2 Emissions, in the Case of a Diesel and LNG Powered Tractor. Eng. Proc. 2024, 79, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ozkan, H.E.; Zhu, H.; Derksen, R.C.; Krause, C.R. Spray Deposition inside Tree Canopies from a Newly Developed Variable-Rate Air-Assisted Sprayer. Trans. ASABE 2013, 56, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Zou, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhai, C. Wind loss model for the thick canopies of orchard trees based on accurate variable spraying. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1010540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, H.; Weisser, P. Spray deposits of crop protection products on plants—The potential exposure of non-target arthropods. Chemosphere 2001, 44, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.; Sinha, R.; Khot, L.R.; Hoheisel, G.-A.; Grieshop, M.J.; Ledebuhr, M. Effect of Emitter Modifications on Spray Performance of a Solid Set Canopy Delivery System in a High-Density Apple Orchard. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doruchowski, G.; Roettele, M.; Herbst, A.; Balsari, P. Drift evaluation tool to raise awareness and support training on the sustainable use of pesticides by drift mitigation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 97, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessler, L.; Nackley, L.; Warneke, B.; Pscheidt, J.; Lockwood, D.; Wright, W.C.; Sun, X.; Fulcher, A. Refining spray application rate with a laser-guided variable-rate sprayer. HortScience 2020, 55, 1522–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Derksen, R.C.; Krause, C.R.; Brazee, R.D.; Reding, M.E.; Zondag, R.H.; Fox, R.D. Spray deposition and off-target loss in nursery tree crops with conventional nozzle, air induction nozzle and drift retardant. In Proceedings of the 2005 ASAE Annual Meeting, Tampa, FL, USA, 17–20 July, 2005; Paper No. 051007. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Application Scenario | Replicate | Wind Azimuth [°] | Wind Velocity [m s−1] | Mean Wind Velocity [m s−1] | Air Temp [°C] | Mean Air Temp [°C] | Air RH [%] | Mean Air RH [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S Symmetrical | I | 310 (NW) | 4.59 | 3.96 | 18.1 | 18.2 | 64.0 | 60.2 |

| II | 293 (W/NW) | 4.60 | 17.9 | 72.5 | ||||

| III | 299 (W/NW) | 2.69 | 18.6 | 44.0 | ||||

| C Compensating | I | 288 (W/NW) | 4.59 | 3.30 | 19.1 | 18.4 | 59.9 | 60.4 |

| II | 270 (W) | 2.66 | 17.2 | 79.5 | ||||

| III | 282 (W/NW) | 2.64 | 19.0 | 41.9 | ||||

| O One-sided | I | 305 (NW) | 5.78 | 4.09 | 18.6 | 18.2 | 67.6 | 61.6 |

| II | 306 (NW) | 3.41 | 16.4 | 79.8 | ||||

| III | 237 (W/SW) | 3.08 | 19.5 | 37.3 |

| Application Scenario with Airflow Setting | Mean Deposit [% of Applied Dose] | Coefficient of Variation CV [%] |

|---|---|---|

| S—Symmetrical emission: L/R = 100%/100% | 59.69 a | 38.0 |

| C—Compensating emission: L/R = 30%/100% | 57.09 a | 54.2 |

| O—One-sided emission: L/R = 0%/100% | 41.70 b | 71.8 |

| Application Scenario with Airflow Setting | Parameters: | |

|---|---|---|

| a | b | |

| S—Symmetrical emission: L/R = 100%/100% | 18.002 | −0.102 |

| C—Compensating emission: L/R = 30%/100% | 7.4218 | −0.107 |

| O—One-sided emission: L/R = 0%/100% | 5.0329 | −0.086 |

| Application Scenario with Airflow Setting | DP [%] | DRP [%] |

|---|---|---|

| S—Symmetrical emission: L/R = 100%/100% | 145.60 | - |

| C—Compensating emission: L/R = 30%/100% | 57.54 | 60.5 |

| O—One-sided emission: L/R = 0%/100% | 46.88 | 67.8 |

| Airflow Setting Scenario | Power Consumption P [kW] | Fuel Consumption F F [L h−1] | CO2 Emission E [kg h−1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| S—Symmetrical | 15.17 | 4.11 | 10.84 |

| C—Compensating crosswind | 11.60 | 3.14 | 8.29 |

| O—One-sided | 10.44 | 2.83 | 7.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Doruchowski, G.; Świechowski, W.; Hołownicki, R.; Godyń, A.; Bartosik, A. Effect of Airflow Settings of an Orchard Sprayer with Two Individually Controlled Fans on Spray Deposition in Apple Trees and Off-Target Drift. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2520. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232520

Doruchowski G, Świechowski W, Hołownicki R, Godyń A, Bartosik A. Effect of Airflow Settings of an Orchard Sprayer with Two Individually Controlled Fans on Spray Deposition in Apple Trees and Off-Target Drift. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2520. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232520

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoruchowski, Grzegorz, Waldemar Świechowski, Ryszard Hołownicki, Artur Godyń, and Andrzej Bartosik. 2025. "Effect of Airflow Settings of an Orchard Sprayer with Two Individually Controlled Fans on Spray Deposition in Apple Trees and Off-Target Drift" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2520. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232520

APA StyleDoruchowski, G., Świechowski, W., Hołownicki, R., Godyń, A., & Bartosik, A. (2025). Effect of Airflow Settings of an Orchard Sprayer with Two Individually Controlled Fans on Spray Deposition in Apple Trees and Off-Target Drift. Agriculture, 15(23), 2520. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232520