Adsorption Performance and Mechanisms of Copper by Soil Glycoprotein-Modified Straw Biochar

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. GRSP Preparation

2.2. Preparation of Straw Biochar

2.3. Preparation of GRSP Modified Straw Biochar

2.4. Copper Adsorption Experiment and Determination of Copper Content

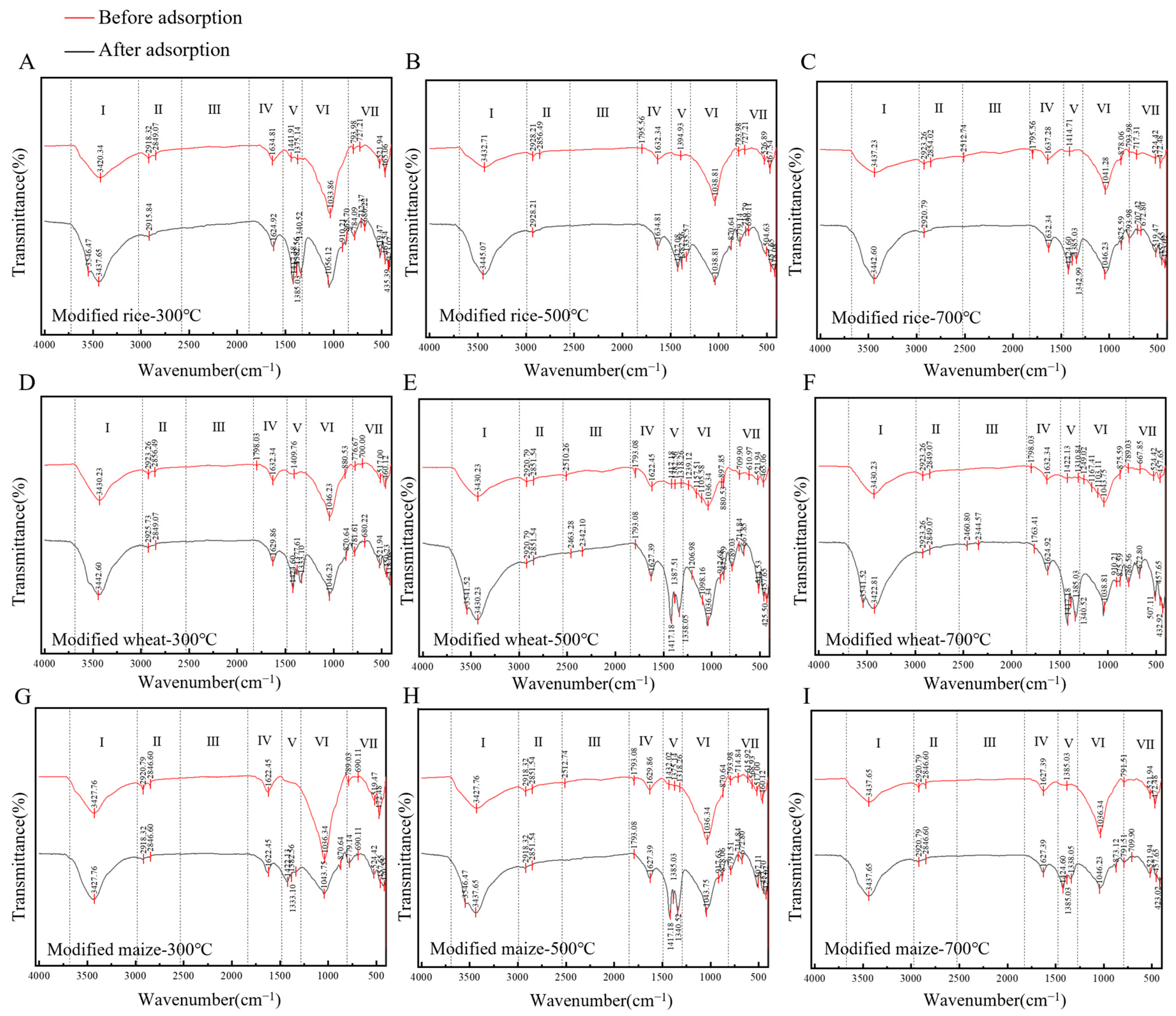

2.5. Characterization by FTIR and SEM-EDS

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

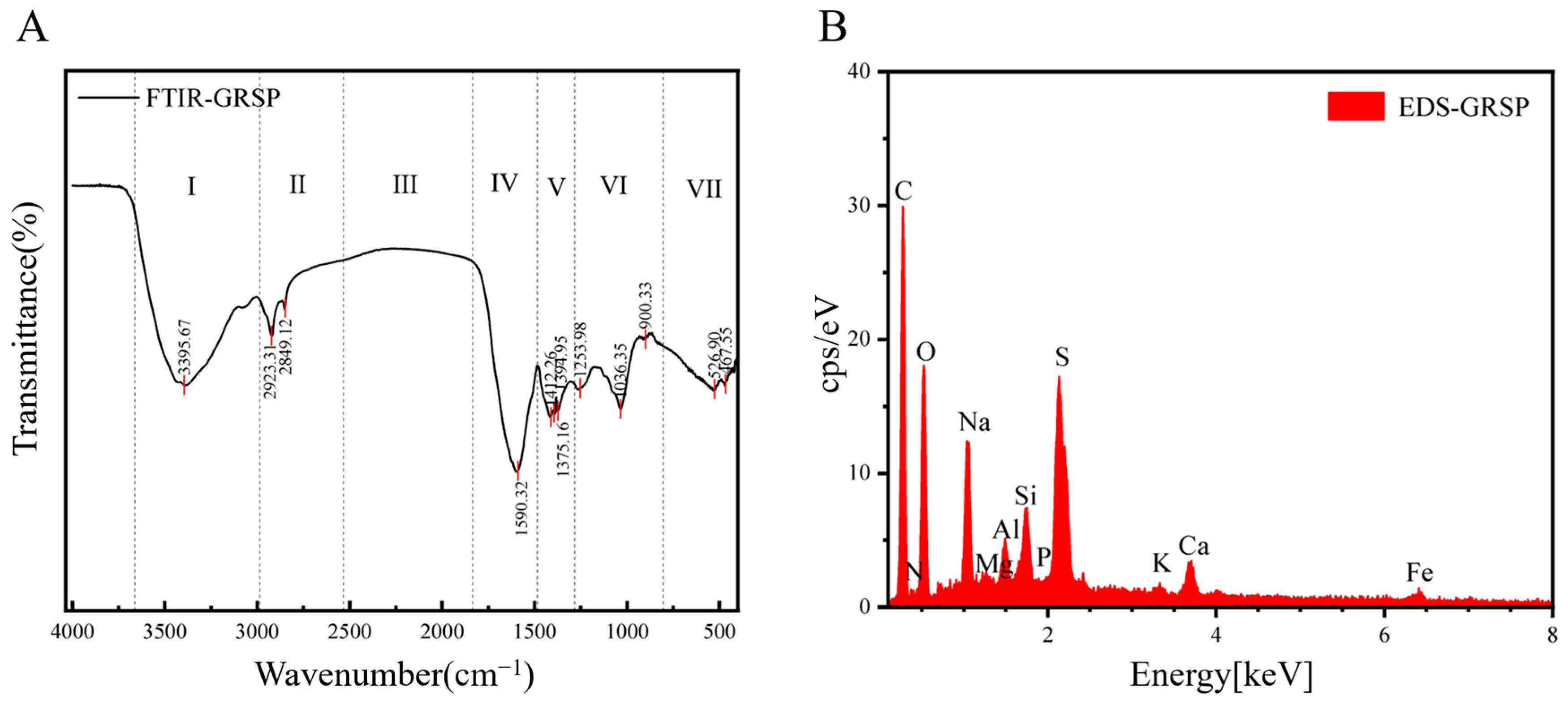

3.1. GRSP Characterization

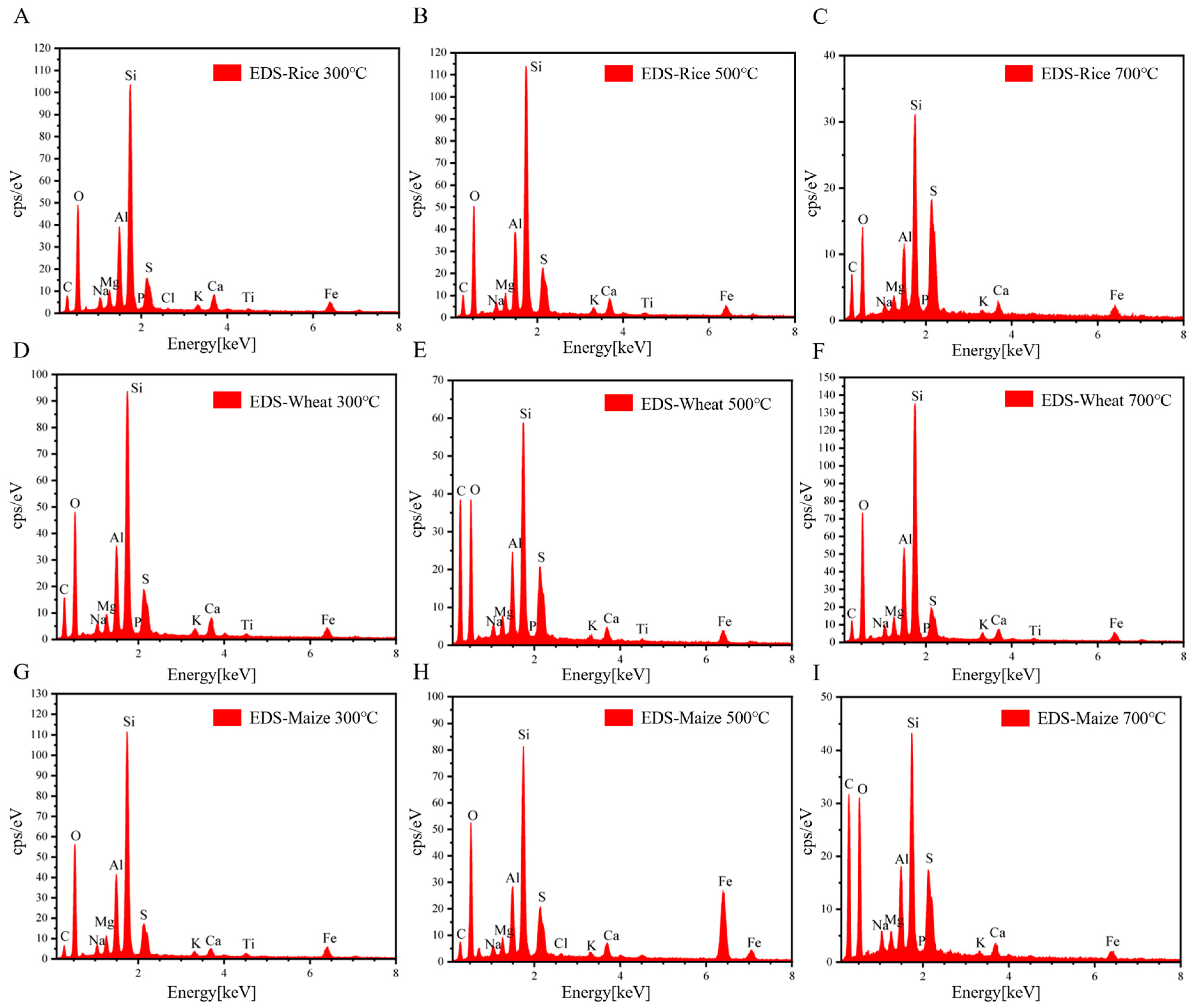

3.2. Characterization of Straw Biochar

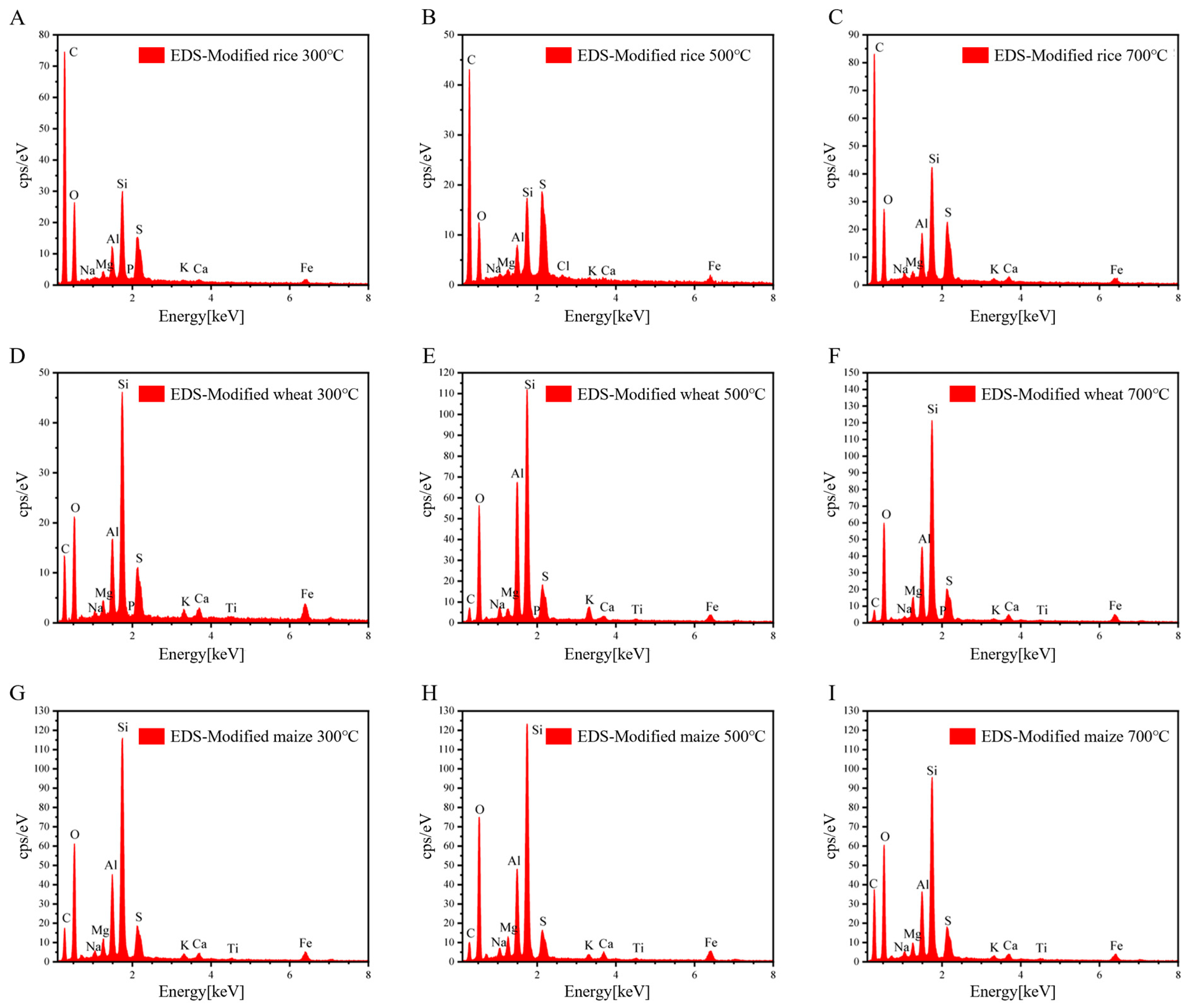

3.3. Characterization of GRSP Modified Straw Biochar

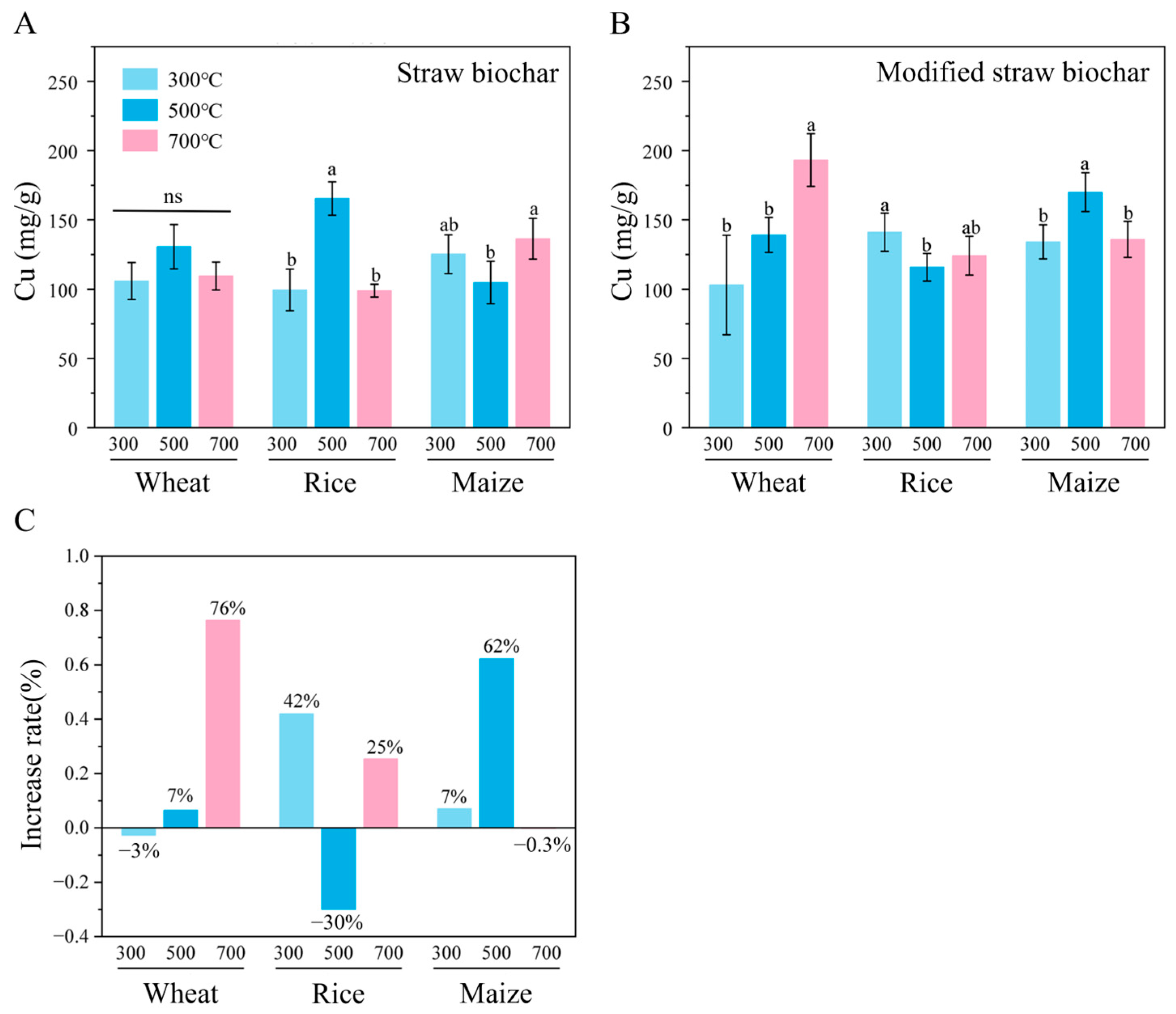

3.4. Adsorption of Copper by Different Types of Straw Biochar

4. Discussion

4.1. GRSP Modified Straw Biochar

4.2. Adsorption Performance of GRSP Modified Straw Biochar for Cu2+

4.3. Adsorption Mechanism of GRSP Modified Straw Biochar for Cu2+

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GRSP | Glomalin-related soil Protein |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| SEM-EDS | Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| Cu | Copper |

References

- Wang, J.; Chen, C. Biosorbents for heavy metals removal and their future. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 195–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Harindintwali, J.D.; Wang, F.; Redmile-Gordon, M.; Chang, S.X.; Fu, Y.; He, C.; Muhoza, B.; Brahushi, F.; Bolan, N.; et al. Integrating Biochar, Bacteria, and Plants for Sustainable Remediation of Soils Contaminated with Organic Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 16546–16566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A. Persistent organic pollutants (POPs): A global issue, a global challenge. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 4223–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Jia, X.; Wang, L.; McGrath, S.P.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, F.-J.; Bank, M.S.; O’Connor, D.; Nriagu, J. Global soil pollution by toxic metals threatens agriculture and human health. Science 2025, 388, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yuan, B.; Yan, C.; Lin, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Lu, H.; Zhu, H.; Hong, H. Extraction and purification of glomalin-related soil protein (GRSP) to determine the associated trace metal(loid)s. Methodsx 2022, 9, 101670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Harris, S.; Anandhi, A.; Chen, G. Predicting biochar properties and functions based on feedstock and pyrolysis temperature: A review and data syntheses. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, N.A.A.; Mohammed, R.H.; Lawal, D.U. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater: A comprehensive and critical review (vol 4, 36, 2021). npj Clean Water 2021, 4, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benis, K.Z.; Soltan, J.; McPhedran, K.N. A novel method for fabrication of a binary oxide biochar composite for oxidative adsorption of arsenite: Characterization, adsorption mechanism and mass transfer modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 356, 131832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P.; Han, L. Effects and mechanism of pyrolysis temperature on physicochemical properties of corn stalk pellet biochar based on combined characterization approach of microcomputed tomography and chemical analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 329, 124907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, P.; Miller, A.Z.; Knicker, H.; Costa-Pereira, M.F.; Merino, A.; Maria De la Rosa, J. Chemical, physical and morphological properties of biochars produced from agricultural residues: Implications for their use as soil amendment. Waste Manag. 2020, 105, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhane, Y.; Belkessa, N.; Bouzaza, A.; Wolbert, D.; Assadi, A.A. Continuous air purification by front flow photocatalytic reactor: Modelling of the influence of mass transfer step under simulated real conditions. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajtor, M.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Prospects for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) to assist in phytoremediation of soil hydrocarbon contaminants. Chemosphere 2016, 162, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, N.; Liu, J.; Guo, Z.; Guan, H.; Bai, Y. A multisource mass transfer model for simulating VOC emissions from paints. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 165945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, V.; de Almeida, D.S.; de Oliveira Miglioranza, G.H.; Steffani, E.; Barbosa-Coutinho, E.; Schwaab, M. Analysis of commonly used batch adsorption kinetic models derived from mass transfer-based modelling. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 79875–79889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Hong, H.; Yang, D.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Pan, C.; Lu, H.; Liu, J.; Yan, C. Health risk assessment of heavy metal and its mitigation by glomalin-related soil protein in sediments along the South China coast. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Masson, V.; Bonhomme, M.; Ginestet, S. Numerical method for solving coupled heat and mass transfer through walls for future integration into an urban climate model. Build. Environ. 2023, 231, 110028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Chávez, M.C.; Carrillo-González, R.; Wright, S.F.; Nichols, K.A. The role of glomalin, a protein produced by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, in sequestering potentially toxic elements. Environ. Pollut. 2004, 130, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, N.A.A.; Fulazzaky, M.A.; Puteh, M.H.; Khamidun, M.H.; Yusoff, A.R.M.; Abdullah, N.H.; Fulazzaky, M.; Zaini, M.A.A. Mass Transfer Kinetics and Mechanisms of Phosphate Adsorbed on Waste Mussel Shell. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhan, L.; Ok, Y.S.; Gao, B. Minireview of potential applications of hydrochar derived from hydrothermal carbonization of biomass. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 57, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zheng, Y.-l.; Lin, Y.-L.; Chen, C.; Yang, F.-Y. Effects of biochar, phosphorus addition and AMF inoculation on switchgrass growth and soil properties under Cd stress. Acta Pratacult. Sin. 2021, 30, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, J. Evaluation of Five Gas Diffusion Models Used in the Gradient Method for Estimating CO2 Flux with Changing Soil Properties. Sustainability 2021, 13, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Finkel, M.; Grathwohl, P. First order approximation for coupled film and intraparticle pore diffusion to model sorption/desorption batch experiments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 429, 128314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, C.H.; Moretti, A.L.; Diorio, A.; Braga, M.U.C.; Scheufele, F.B.; Barros, M.A.S.D.; Arroyo, P.A. The influence of electrolytes in the adsorption kinetics of reactive BF-5G blue dye on bone char: A mass transfer model. Environ. Technol. 2024, 45, 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgin, J.; Franco, D.S.P.; Netto, M.S.; de Salomon, Y.L.O.; Piccilli, D.G.A.; Foletto, E.L.; Dotto, G.L. Adsorption and mass transfer studies of methylene blue onto comminuted seedpods from Luehea divaricata and Inga laurina. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 20854–20868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Gao, P.; Chu, G.; Pan, B.; Peng, J.; Xing, B. Enhanced adsorption of Cu(II) and Cd(II) by phosphoric acid-modified biochars. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 229, 846–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Liao, B.; Lin, L.; Qiu, W.; Song, Z. Adsorption of Cu(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solutions by ferromanganese binary oxide-biochar composites. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-X.; Jiang, H. Amino modification of biochar for enhanced adsorption of copper ions from synthetic wastewater. Water Res. 2014, 48, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Yin, W.; Bo, S.; Jin-Fa, L.; Ren-Xue, X.J.P. Relationships between arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis and soil fertility factors in citrus orchards along an altitudinal gradient. Pedosphere 2015, 25, 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger, H.; Walker, C.; Schuessler, A. ‘Glomus intraradices DAOM197198′, a model fungus in arbuscular mycorrhiza research, is not Glomus intraradices. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 1176–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C. Arbuscular mycorrhizae, glomalin, and soil aggregation. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2004, 84, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lu, H.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Williams, M.A.; Wu, S.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, G.; Yan, C. Interactions of soil metals with glomalin-related soil protein as soil pollution bioindicators in mangrove wetland ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 136051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wei, J.; Qi, S.; Wu, B.; Cheng, S. Sustainable Remediation of Soil and Water Utilizing Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi: A Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Xiong, J.; Fang, L.; Han, F.; Zhao, X.; Fan, Q.; Tan, W. Sequestration of heavy metals in soil aggregates induced by glomalin-related soil protein: A five-year phytoremediation field study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 437, 129445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Mei, D.; Chen, J.; Lin, Y.; Liu, J.; Lu, H.; Yan, C. Sequestration of heavy metal by glomalin-related soil protein: Implication for water quality improvement in mangrove wetlands. Water Res. 2019, 148, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Ledezma, C.; Negrete-Bolagay, D.; Figueroa, F.; Zamora-Ledezma, E.; Ni, M.; Alexis, F.; Guerrero, V.H. Heavy metal water pollution: A fresh look about hazards, novel and conventional remediation methods. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 22, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Liu, L.; Ling, Q.; Cai, Y.; Yu, S.; Wang, S.; Fu, D.; Hu, B.; Wang, X. Biochar for the removal of contaminants from soil and water: A review. Biochar 2022, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.; Wang, B.; Wu, P.; Lee, X.; Xing, Y.; Chen, M.; Gao, B. Adsorption of emerging contaminants from water and wastewater by modified biochar: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, A.U.; Chen, S.S.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Zhang, M.; Vithanage, M.; Mandal, S.; Gao, B.; Bolan, N.S.; Ok, Y.S. Engineered/designer biochar for contaminant removal/immobilization from soil and water: Potential and implication of biochar modification. Chemosphere 2016, 148, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Bai, X.; Wu, D.; Li, F.; Jiang, K.; Ma, N.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Fang, L. Sulfur-functional group tunning on biochar through sodium thiosulfate modified molten salt process for efficient heavy metal adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 134441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Yuan, B.; Wang, Y.; Cao, W.; Liu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Liu, Q. Improving Cu(II) sorption by biochar via pyrolyzation under CO2: The importance of inherent inorganic species. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 5105–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, M.; Kumar, R.; Neogi, S. Activated biochar derived from Opuntia ficus-indica for the efficient adsorption of malachite green dye, Cu+2 and Ni+2 from water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 392, 122441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, H. Biochar/MnAl-LDH composites for Cu (II) removal from aqueous solution. Colloids Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 538, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, K.; Yin, H.; Cai, Y.; Yan, C.; Yuan, Y.; Ouyang, X. Simultaneous removal of As (III) and Cu (II) by biochar modified siderite: The key roles of ROS and mineral conversion. J. Environ. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Gao, Z.; Xue, Y.; Yao, X.; Shao, H.; Wang, Q. Adsorption Performance and Mechanisms of Copper by Soil Glycoprotein-Modified Straw Biochar. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2495. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232495

Chen Z, Gao Z, Xue Y, Yao X, Shao H, Wang Q. Adsorption Performance and Mechanisms of Copper by Soil Glycoprotein-Modified Straw Biochar. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2495. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232495

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zhenyu, Zhiyuan Gao, Yiyuan Xue, Xinchi Yao, Haiyan Shao, and Qiang Wang. 2025. "Adsorption Performance and Mechanisms of Copper by Soil Glycoprotein-Modified Straw Biochar" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2495. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232495

APA StyleChen, Z., Gao, Z., Xue, Y., Yao, X., Shao, H., & Wang, Q. (2025). Adsorption Performance and Mechanisms of Copper by Soil Glycoprotein-Modified Straw Biochar. Agriculture, 15(23), 2495. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232495