Virtuous and Vicious Circles in Organic Agriculture: A Comparative Typology Between Denmark and Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Danish Organic Production Development

2.2. Brazilian Organic Production Development

3. Materials and Methods

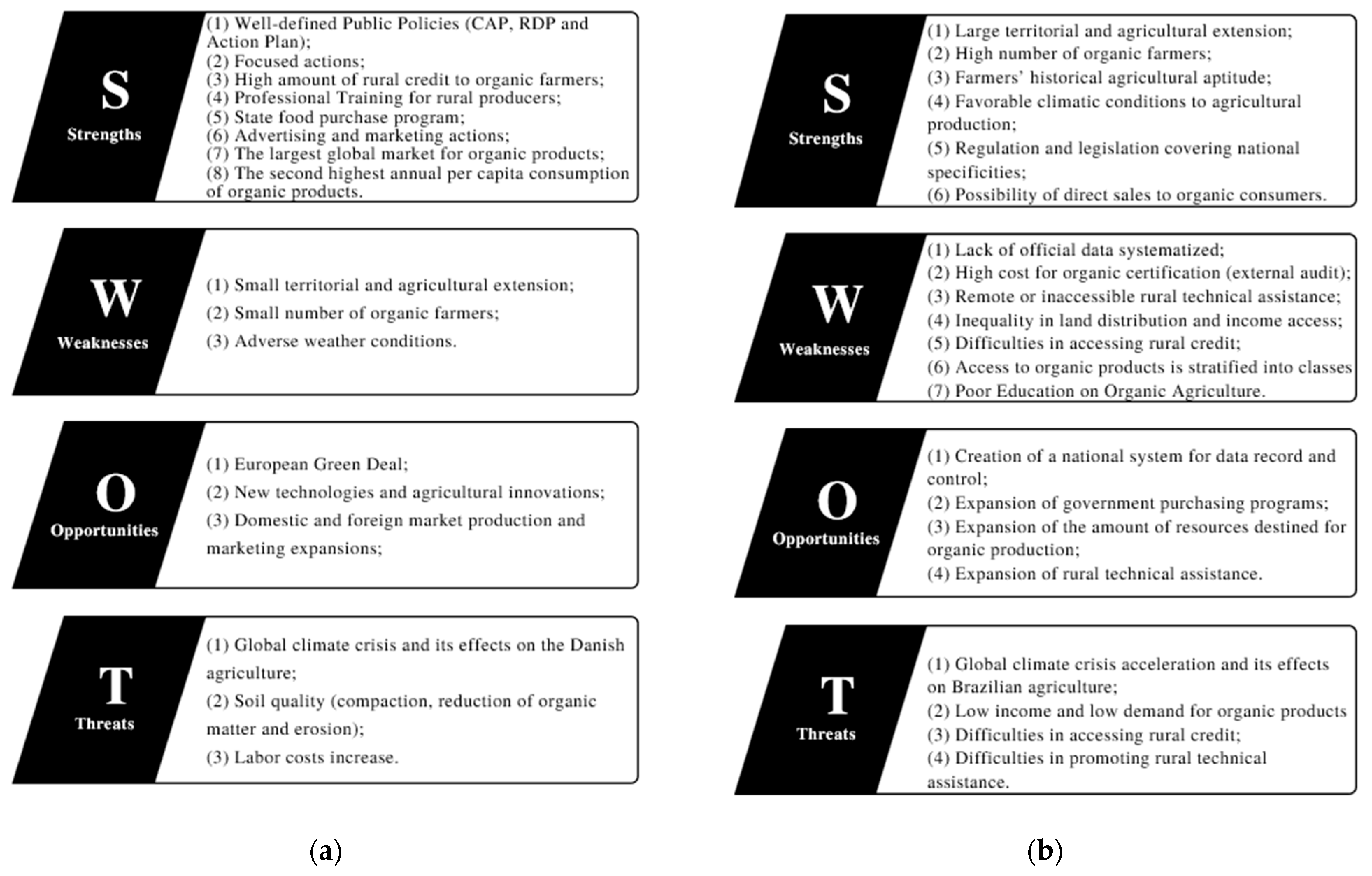

3.1. SWOT Analysis Applied to the Danish and Brazilian Organic Production

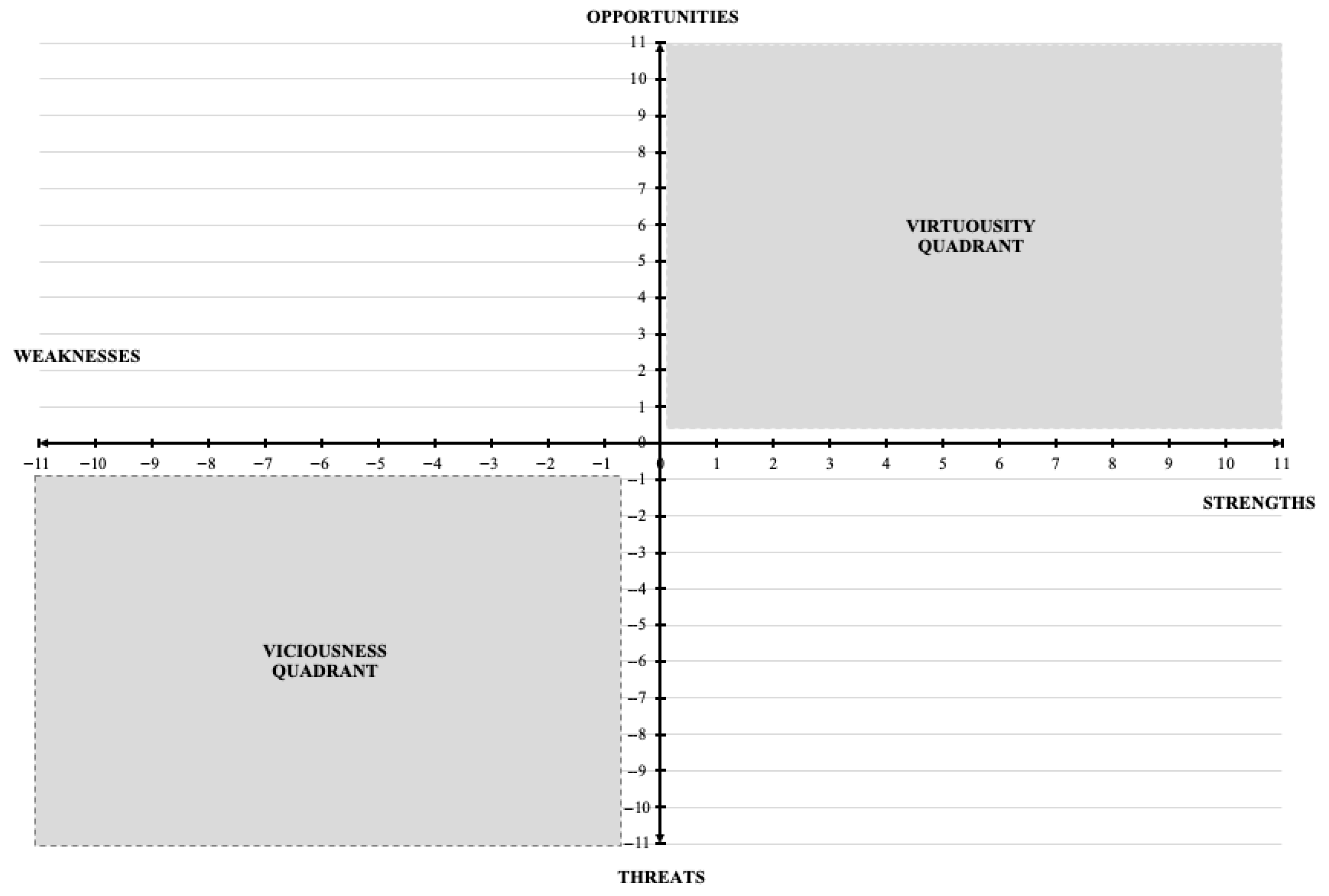

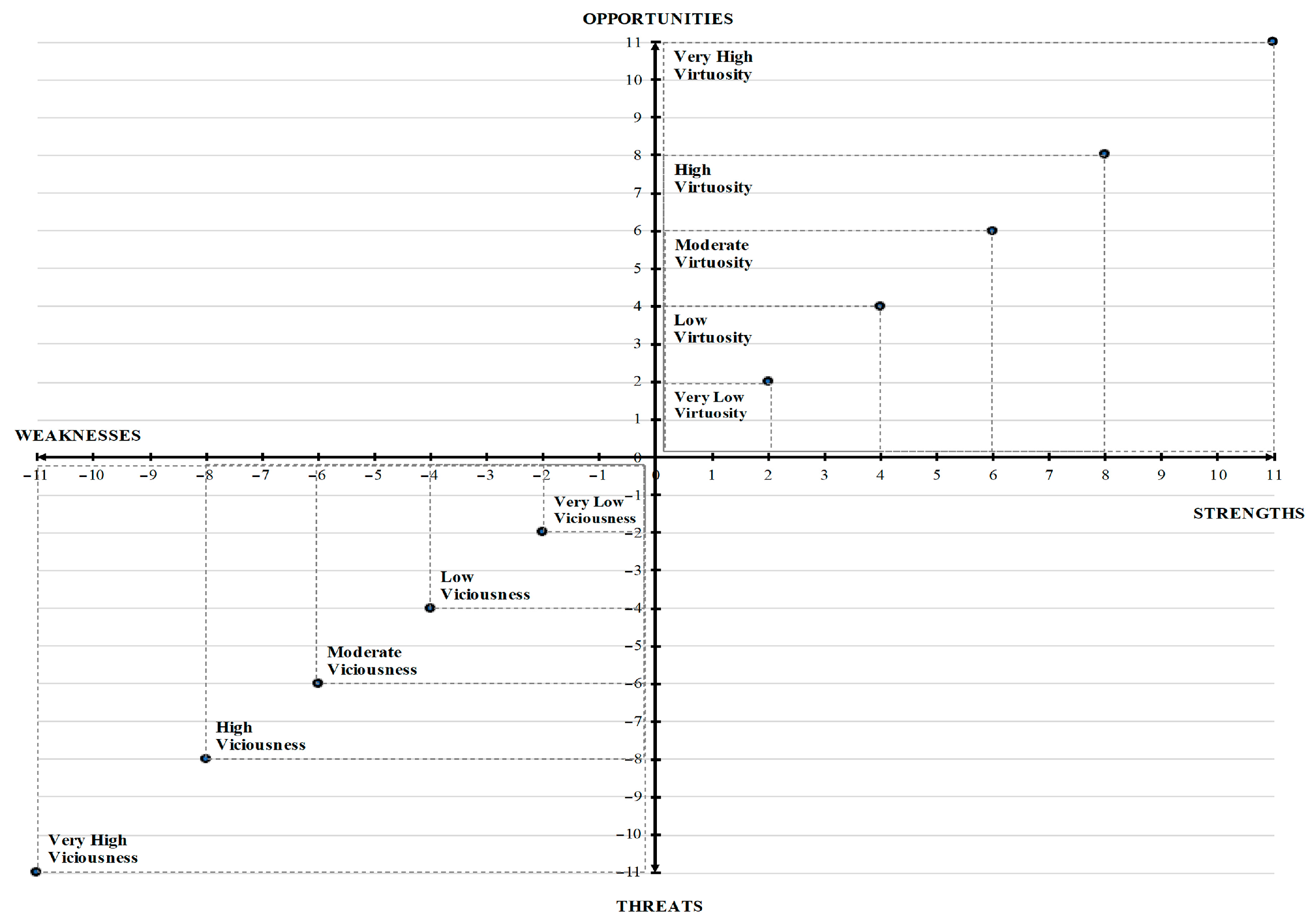

3.2. Factorial Space Construction

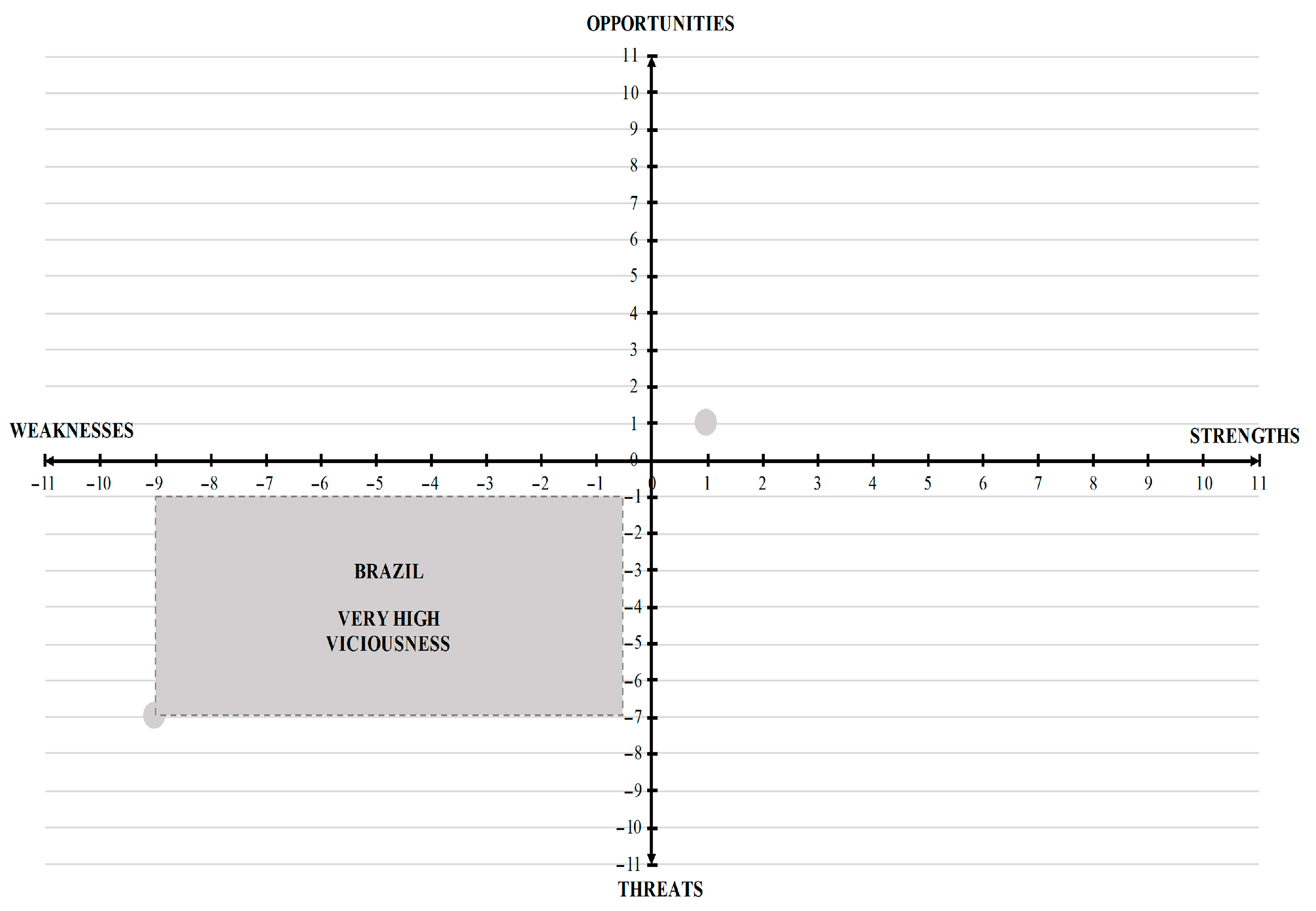

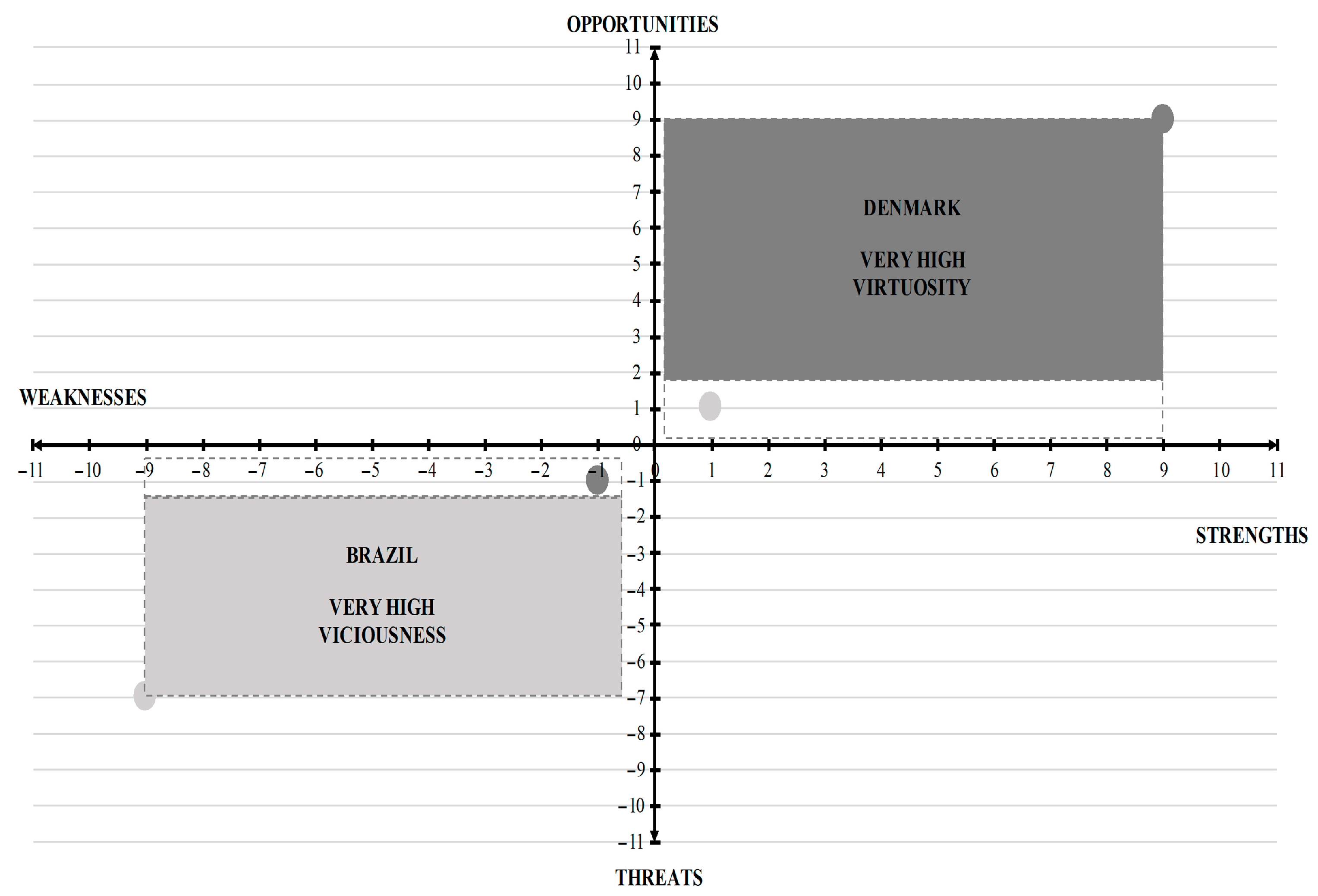

- Virtuous Quadrant: Factor 1: Strengths (positive X-Axis) versus Factor 2: Opportunities (positive Y-Axis). This factorial space was determined as the Virtuous Quadrant. To be in this quadrant, the country should receive scores of +1 (plus 1) or 0 (zero) in all determinant variables of the critical factors.

- Vicious Quadrant: Factor 1: Weaknesses (negative X-Axis) versus Factor 2: Threats (negative Y-Axis). This factorial space was determined to be the Vicious Quadrant. To be in this quadrant, the country should receive scores of −1 (minus 1) or 0 (zero) in all determinant variables of the critical factors.

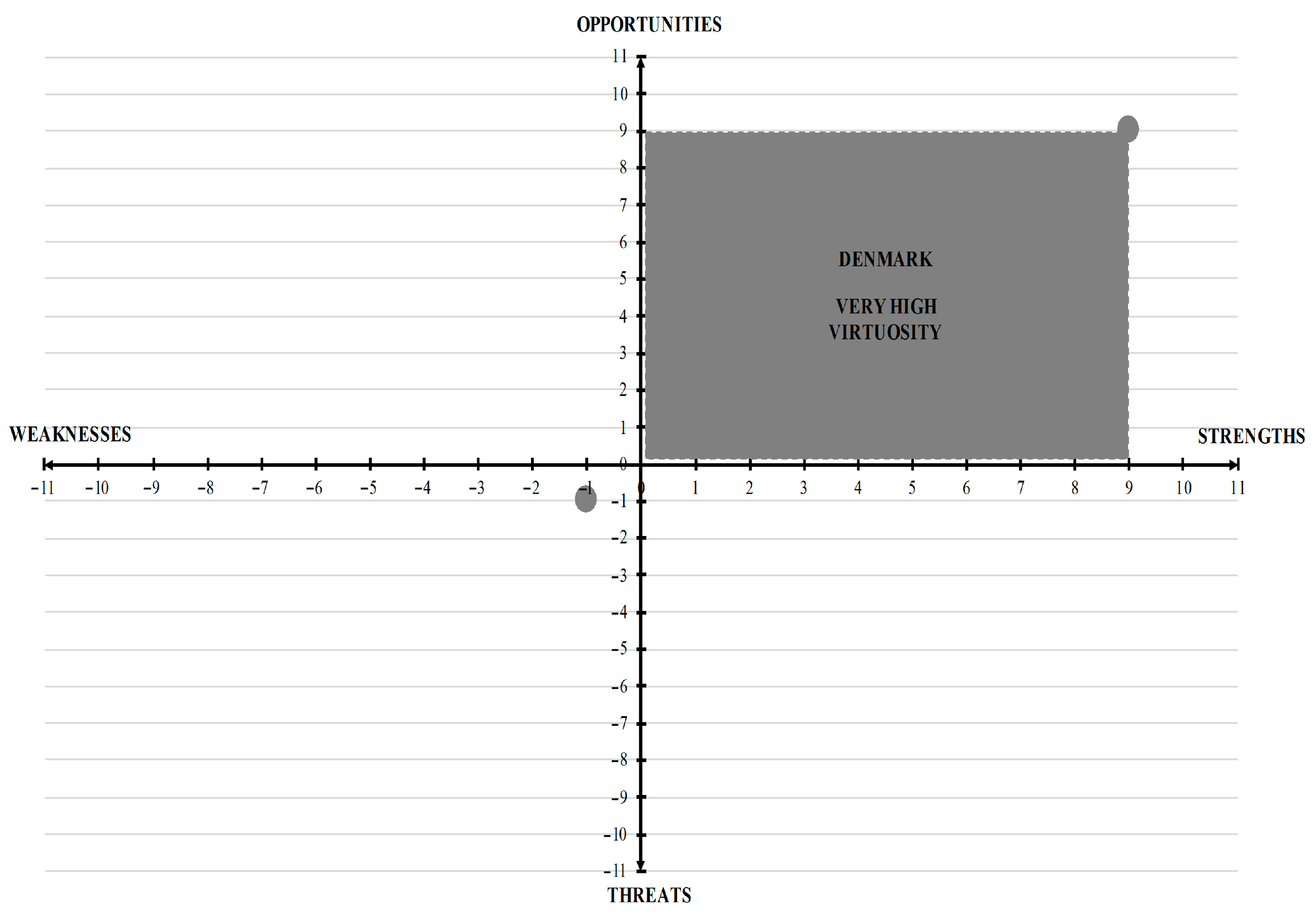

4. Results

4.1. Danish Organic Agriculture

4.2. Brazilian Organic Agriculture

5. Discussion

5.1. The Danish Context

5.2. The Brazilian Scenario

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAP | Danish action plans for organic farming |

| AS-PTA | Advice and Services-Alternative Agriculture Project |

| DKK | Danish Krone (Danish currency) |

| CPOrg | Organic Production Commission of São Paulo |

| DØJ | Danish Organic Agriculture National School |

| EBAA | Brazilian Alternative Agriculture Meetings |

| EMBRAPA | Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FDB | Danish retail group (supermarket) |

| IDB | Inter-American Development Bank |

| LØJ | Danish National Association of Organic Agriculture |

| MAPA | Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Supply |

| NGO’s | Non-Governmental Organizations |

| PGPM-Bio | Brazilian Minimum Price Guarantee Policy for Socio-Biodiversity Products |

| PNAE | Brazilian National School Feeding Program |

| PNSAN | Brazilian National Food and Nutrition Security Policy |

| PRONAF | Brazilian National Program to Strengthen Family Farming |

| PTA | Alternative Technologies Project Network |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SISOrg | Brazilian Organic Conformity Assessment System |

| SNCR | Brazilian National Program for Rural Credit for Conventional Agriculture |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats |

| UNCED | United Nations Conference on Environment and Development |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

References

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.; Tignor, M.; Poloczanska, E.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; et al. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; p. 3056. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. General Assembly Resolution A/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- UNEP. United Nations Environment Programme. Global Resources Outlook 2024: Bend the Trend—Pathways to a Liveable Planet as Resource Use Spikes; International Resource Panel: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Helga, W.; Trávníček, J.; Schlatter, B. (Eds.) The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2024; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL, Frick, and IFOAM—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Helga, W.; Trávníček, J.; Schlatter, B. (Eds.) The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2025; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL, Frick, and IFOAM—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE. Agricultural Census 2017; Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, L.F.; Abreu, L.S.; Romeiro, A.R. Políticas públicas e o desenvolvimento de sistemas agroalimentares orgânicos: O caso da Dinamarca. Rev. Bras. Agroecol. 2023, 18, 724–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.F. Análise Comparada da Trajetória do Desenvolvimento da Agricultura Orgânica no Brasil e na Dinamarca. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Economia, Campinas, Brasil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ingemann, J.H. The Evolution of Organic Agriculture in Denmark; OASE Working Paper No. 2006: 4. Economics, Politics and Public Administration; Aalborg University: Aalborg, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, J. Alternativer-Natur-Landbrug; Akademisk Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Geer, T.; Jørgensen, T.V. Ø-Mærket; Erhvervsskolernes Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Statistik Danmarks. Organic Production and Trade—2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/emner/miljoe-og-energi/oekologi (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Sørensen, N.N.; Lassen, A.D.; Løje, H.; Tetens, I. The Danish Organic Action Plan 2020: Assessment method and baseline status of organic procurement in public kitchens. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 23502357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlers, E. Agricultura Sustentável: Origens e Perspectivas de um Novo Paradigma; Livros da Terra: São Paulo, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, E. A agricultura alternativa: Uma visão histórica. Estud. Econômicos 1994, 24, 231–262. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, F.F.; Rigotto, R.M.; da Silva Augusto, L.G.; Friedrich, K.; Burigo, A.C. Dossiê ABRASCO: Um Alerta Sobre os Impactos dos Agrotóxicos na Saúde; EPSJV: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Expressão Popular: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bombardi, L.M. Geografia do Uso de Agrotóxicos no Brasil e Conexões com a União Europeia; FFLCH-USP: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bombardi, L.M. Agrotóxicos e Colonialismo Químico; Editora Elefante: São Paulo, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abreu, L.S.; Bellon, S.; Brandenburg, A.; Ollivier, G.; Lamine, C.; Darolt, M.R.; Aventurier, P. Relações entre agricultura orgânica e agroecologia: Desafios atuais em torno dos princípios da agroecologia. Desenvolv. Meio Ambiente 2012, 26, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, R.L.; Romeiro, A.R. Agroecologia e agricultura orgânica: Controvérsias e tendências. Desenvolv. Meio Ambiente 2002, 6, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianna, A. Agricultura Orgânica: A Subjacente Construção de Relações Sociais e Saberes. Master’s Thesis, CPDA/UFRRJ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, I.F. Antecedentes e aspectos fundantes da agroecologia e da produção orgânica na agenda das políticas públicas no Brasil. In A Política Nacional de Agroecologia e Produção Orgânica no Brasil: Uma Trajetória de Luta Pelo Desenvolvimento Rural Sustentável; Sambuichi, R.H.R., Moura, I.F.d., Mattos, L.M.d., Avila, M.L.d., Spinola, P.A.C., Silva, A.P.M.d., Eds.; IPEA: Brasília, Brazil, 2017; pp. 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, M.F.A.C. Agricultura Orgânica: Regulamentos Técnicos para Acesso aos Mercados dos Produtos Orgânicos no Brasil; Pesagro-Rio: Niterói, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grisa, C.; Schneider, S. Políticas Públicas de Desenvolvimento Rural no Brasil; Editora da UFRGS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Von Der Weid, J.M. Construindo políticas públicas em apoio à agroecologia. Agric. Práticas Políticas Públicas 2006, 3, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- EMBRAPA. Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária. Marco Referencial em Agroecologia; Embrapa Informação Tecnológica: Brasília, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Decreto N.º 7.272, de 25 de Agosto de 2010. Regulamenta a Lei no 11.346, de 15 de Setembro de 2006, que cria o Sistema Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional—Sisan, com Vistas a Assegurar o Direito Humano à Alimentação Adequada, Institui a Política Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional—PNSAN, Estabelece os Parâmetros para a Elaboração do Plano Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional, e dá Outras Providências; Presidência da República: Brasília, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, C.J.; Grisa, C. Agroecologia, mercados e políticas públicas: Uma análise a partir dos instrumentos de ação governamental. In Agroecologia: Práticas, Mercados e Políticas Para uma Nova Agricultura; Nierdele, P.A., Almeida, L., Vezzani, F.M., Eds.; Kairós: Curitiba, Brazil, 2013; pp. 215–266. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Decreto Nº 1.946, de 28 de Junho de 1996. Cria o Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar—PRONAF e dá Outras Providências; Presidência da República: Brasília, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bojanic, A.J.; França, C.G.D.; Marques, V.P.M.D.A.; Del Grossi, M.E. Superação da Fome e da Pobreza Rural: Iniciativas Brasileiras; Organização das Nações Unidas para a Alimentação e a Agricultura (FAO): Brasília, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Plano Nacional de Agroecologia e Produção Orgânica: Relatório de Balanço 2013–2015; MDA: Brasília, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wesz Junior, V.J. O PRONAF pós-2014: Intensificando a sua seletividade? Dossiê: PRONAF 25 anos: Histórico, transformações e tendências. Revista Grifos-Unochapecó 2020, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossá, J.L.; da Luz, A.A.; Renk, A.A.; Villwock, A.P.S.; Matte, A. A falta de financiamento de crédito rural: Reflexões a partir do PRONAF linhas “verdes”. Colóquio-Rev. Desenvolv. Reg. 2023, 20, 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, L.; Romeiro, A.R.; Abreu, L.S.; Mangabeira, J.A.C. Construção de uma tipologia para a produção orgânica no Brasil. In Proceedings of the Congresso da Sociedade Brasileira de Economia, Administração e Sociologia Rural, Brasília, Brazil, 2 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarche, H. A Agricultura Familiar, Comparação Internacional; Unicamp: Campinas, Brazil, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche, H. L’Agriculture Familiale II: Du Mythe à la Réalité; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, L.D.; Bana e Costa, C.A. Transparent prioritisation, budgeting, and resource allocation with multi-criteria decision analysis and decision conferencing. Ann. Oper. Res. 2007, 154, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bana e Costa, C.A.B.; Ensslin, L.; Cornêa, É.C.; Vansnick, J.C. Decision support systems in action: Integrated application in a multicriteria decision aid process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1999, 113, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bana e Costa, C.A.B.; Vansnick, J.C. MACBETH—An Interactive Path Towards the Construction of Cardinal Value Functions. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 1994, 1, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioro, N.P.X. Sistemas Técnicos de Produção Agrícola: O caso do município de Morretes. In Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente-em Busca da Interdisciplinaridade; Raynaut, C., Ed.; UFPR: Curitiba, Brazil, 2002; Capter 3; pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Buainain, A.M.; Batalha, M.O. Cadeia Produtiva de Produtos Orgânicos. Série Agronegócios, Brasília, 2007. Available online: https://repositorio-dspace.agricultura.gov.br/bitstream/1/497/1/BR0704923.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Assad, E.D.; Lopes-Assad, M.L. Mudanças do clima e agropecuária: Impactos, mitigação e adaptação. Desafios e oportunidades. Estud. Avançados 2024, 38, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, M. Exploring Policy Approaches for Further Development of Organic Farming in Denmark. J. Rural Probl. 2024, 60, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFOAM Organics Europe. Environmental Impacts of Achieving the EU’s 25% Organic Land Target by 2030: A Preliminary Assessment. Report for IFOAM Organics Europe, Brussels, 2022. Available online: https://www.organicseurope.bio/library/environmental-impacts-of-achieving-the-eus-25-organic-land-by-2030-target-a-preliminary-assessment/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Olesen, J.E. Organic farming and the challenges of climate change. Ecol. Farming 2009, 44, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Schjønning, P.G.; Heckrath, G.; Christensen, B.T. Threats to Soil Quality in Denmark: A Review of Existing Knowledge in the EU Soil Thematic Strategy Context; DJF Report Plant Science No. 143; Aarhus University, Det Jordbrugsvidenskabelige Fakultet: Aarhus, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, J.; Bones, C.; Clinton, L.; Dodgson, C.; Bennett, T.; Bragg, N.; Cross, J.; Houston, S.; Stevenson, A.; Tipples, J.; et al. Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board Annual Report and Accounts 2011/12. 2011. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7b7d9d40f0b62826a03ec7/0238.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Lima, L.O.; Medeiros, M.B.; Silva, M.J.R. Identificação das dificuldades de acesso ao PRONAF pelos agricultores familiares no Nordeste brasileiro. Rev. Extensão Univasf Pet. 2019, 7, 6–25. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, R.d.S.; Rodrigues, M.S.; de Souza, R.F.; Olinda, D.R. Challenges and perspectives related to climate change and food security in Brazil. Rev. Multidiscip. Nordeste Min. 2025, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, A.C.O.; Angelkorte, G.B.; Bakman, T.; Baptista, L.B.; Cruz, T.; Diuana, F.A.; Morais, T.N.; Rathmann, R.; Silva, F.d.; Tagomori, I.S.; et al. How climate change is impacting the Brazilian agricultural sector: Evidence from a systematic literature review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | Virtuosity (Number of Scores +1) | Viciousness (Number of Scores −1) |

|---|---|---|

| Very Low | up to 2 variables | up to 2 variables |

| Low | between 3 and 4 variables | between 3 and 4 variables |

| Moderate | between 5 and 6 variables | between 5 and 6 variables |

| High | between 7 and 8 variables | between 7 and 8 variables |

| Very High | between 9 and 11 variables | between 9 and 11 variables |

| Denmark | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Factors | Strengths (Scores: +1 or 0) | Opportunities (Scores: +1 or 0) | Weaknesses (Scores: −1 or 0) | Threats (Scores: −1 or 0) |

| 1. Demand | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. Supply | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 |

| 3. Trade and International Negotiations | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4. Product Safety | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Research Support | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. Technical Assistance and Rural Extension | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 7. Access to Rural Credit | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 8. Education Support | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9. Market Access | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 10. Relationship between public and private agents | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 11. Climate crisis and its effects on agriculture | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 |

| Results | 9 | 9 | −1 | −1 |

| Brazil | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Factors | Strengths (Scores: +1 or 0) | Opportunities (Scores: +1 or 0) | Weaknesses (Scores: −1 or 0) | Threats (Scores: −1 or 0) |

| 1. Demand | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 |

| 2. Supply | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 |

| 3. Trade and International Negotiations | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 |

| 4. Product Safety | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Research Support | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 |

| 6. Technical Assistance and Rural Extension | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 |

| 7. Access to Rural Credit | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 |

| 8. Education Support | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 |

| 9. Market Access | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 |

| 10. Relationship between public and private agents | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 |

| 11. Climate crisis and its effects on agriculture | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 |

| Results | 1 | 1 | −9 | −7 |

| Public Policies | Impacted Critical Factors | Responsible for Policy Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Promotion of production (support for land transfers and tax incentives) | 2, 3, 7, 9, 10 | Federal Government |

| Rural infrastructure (electrification, roads, internet, and water) | 2, 3, 6, 9, 10 | Federal and State Governments |

| Technical assistance and rural extension | 2, 5, 6, 8 | Federal, State, and Municipal Governments |

| Support for fairs and short marketing circuits | 1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 10 | Municipal Governments |

| Government purchases and other demand-generation instruments for family farming production | 2, 9, 10 | Federal, State, and Municipal Governments |

| Policies for the recognition and protection of Indigenous and Traditional Communities’ Territories | 2, 5, 8, 11 | Federal Government |

| Support for the rescue and multiplication of creole seeds (Community Seed Banks—CSB) | 2, 5, 6, 11 | Federal, State, and Municipal Governments and NGO’s |

| Support for rural women and youth groups | 1, 2, 7, 10 | Federal, State, and Municipal Governments |

| Promotion of adequate and healthy food by marketing and advertising | 1, 2, 5, 8, 10 | Federal Government |

| Degraded areas recovery | 2, 3, 11 | Federal, State, and Municipal governments |

| Urban Agriculture | 1, 2, 9, 7 | Municipal Governments and NGO’s |

| Expansion of the Organic Production Commission action scope | 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10 | Federal Government |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lima, L.F.; Romeiro, A.R.; Abreu, L.S.d.; Mangabeira, J.A.d.C.; Tôsto, S.G. Virtuous and Vicious Circles in Organic Agriculture: A Comparative Typology Between Denmark and Brazil. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232429

Lima LF, Romeiro AR, Abreu LSd, Mangabeira JAdC, Tôsto SG. Virtuous and Vicious Circles in Organic Agriculture: A Comparative Typology Between Denmark and Brazil. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232429

Chicago/Turabian StyleLima, Lucas Ferreira, Ademar Ribeiro Romeiro, Lucimar Santiago de Abreu, João Alfredo de Carvalho Mangabeira, and Sérgio Gomes Tôsto. 2025. "Virtuous and Vicious Circles in Organic Agriculture: A Comparative Typology Between Denmark and Brazil" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232429

APA StyleLima, L. F., Romeiro, A. R., Abreu, L. S. d., Mangabeira, J. A. d. C., & Tôsto, S. G. (2025). Virtuous and Vicious Circles in Organic Agriculture: A Comparative Typology Between Denmark and Brazil. Agriculture, 15(23), 2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232429