Study on the Detection Model of Tea Red Scab Severity Class Using Hyperspectral Imaging Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

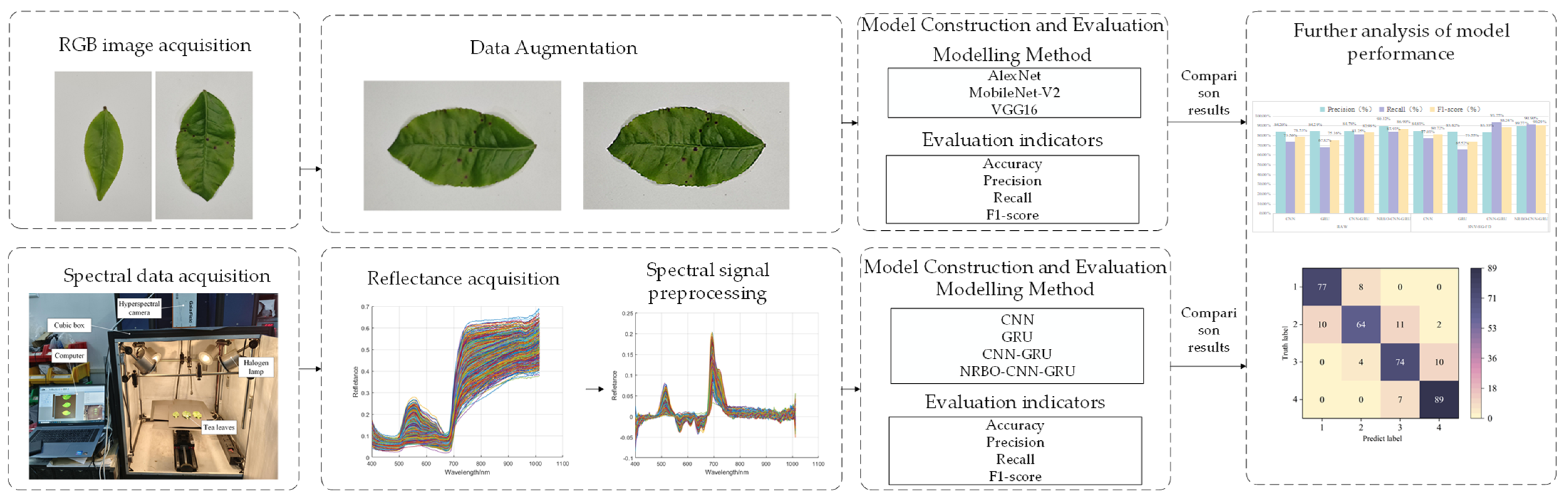

2. Materials and Methods

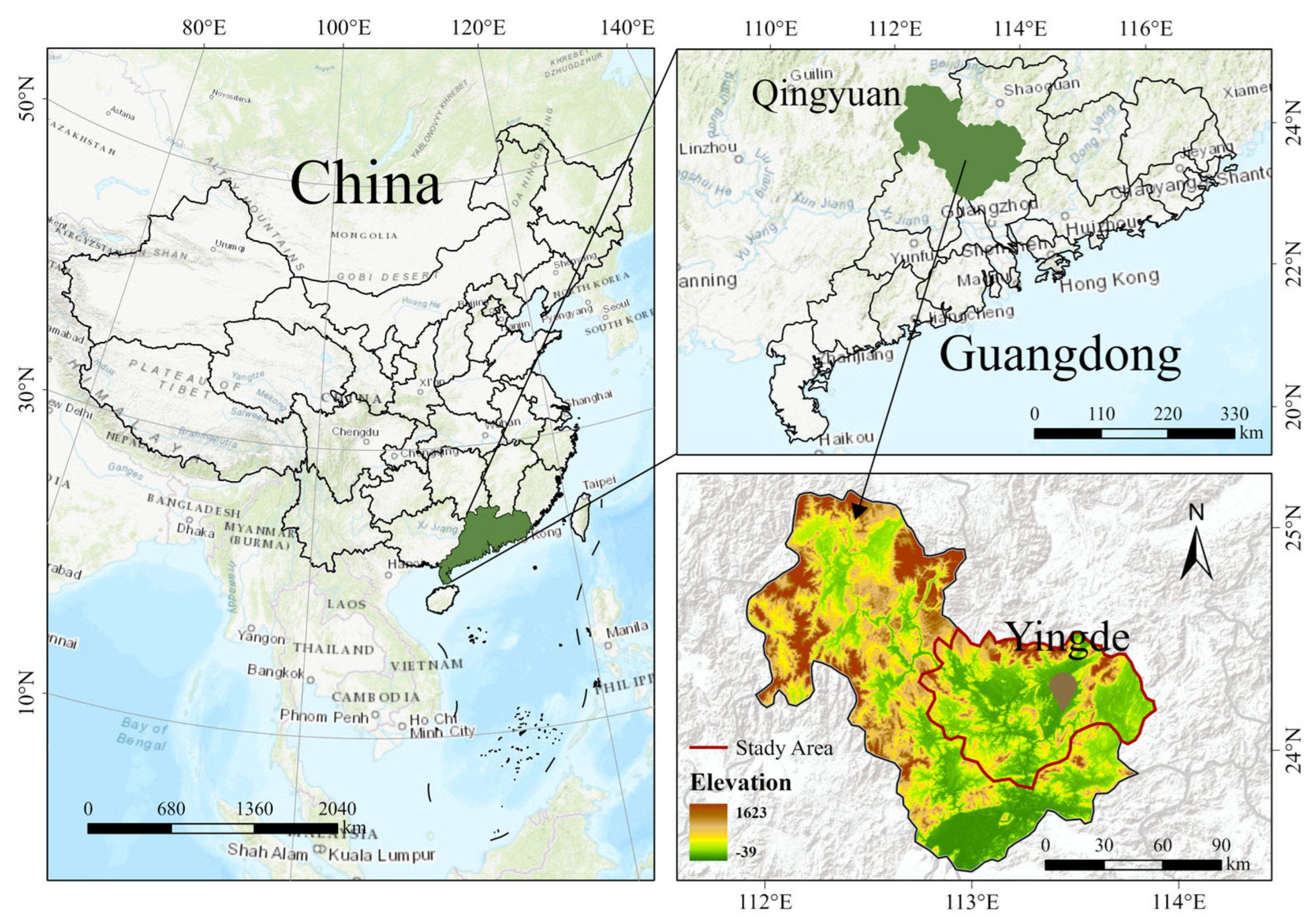

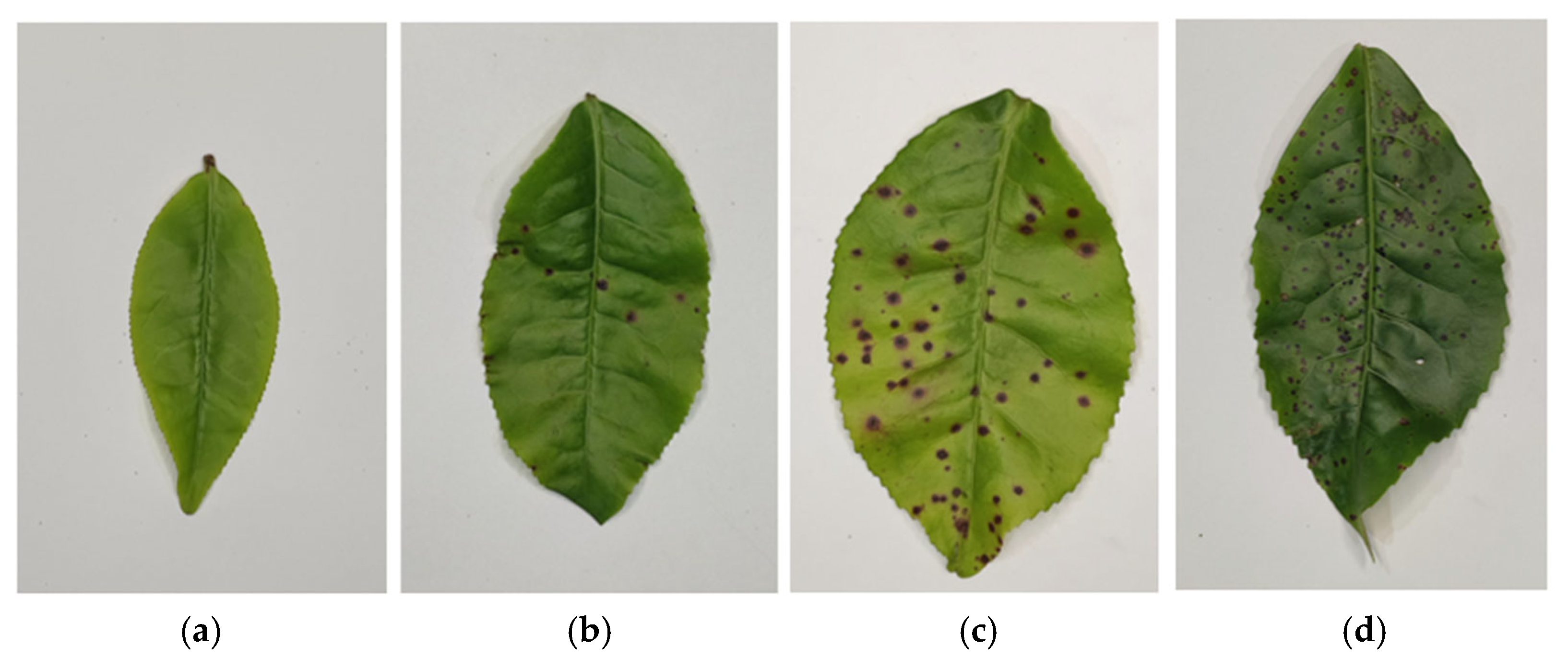

2.1. Acquisition of Tea Red Scab Samples and Disease Classification

2.2. RGB Image Processing Methods and Model Construction

2.2.1. RGB Image Preprocessing

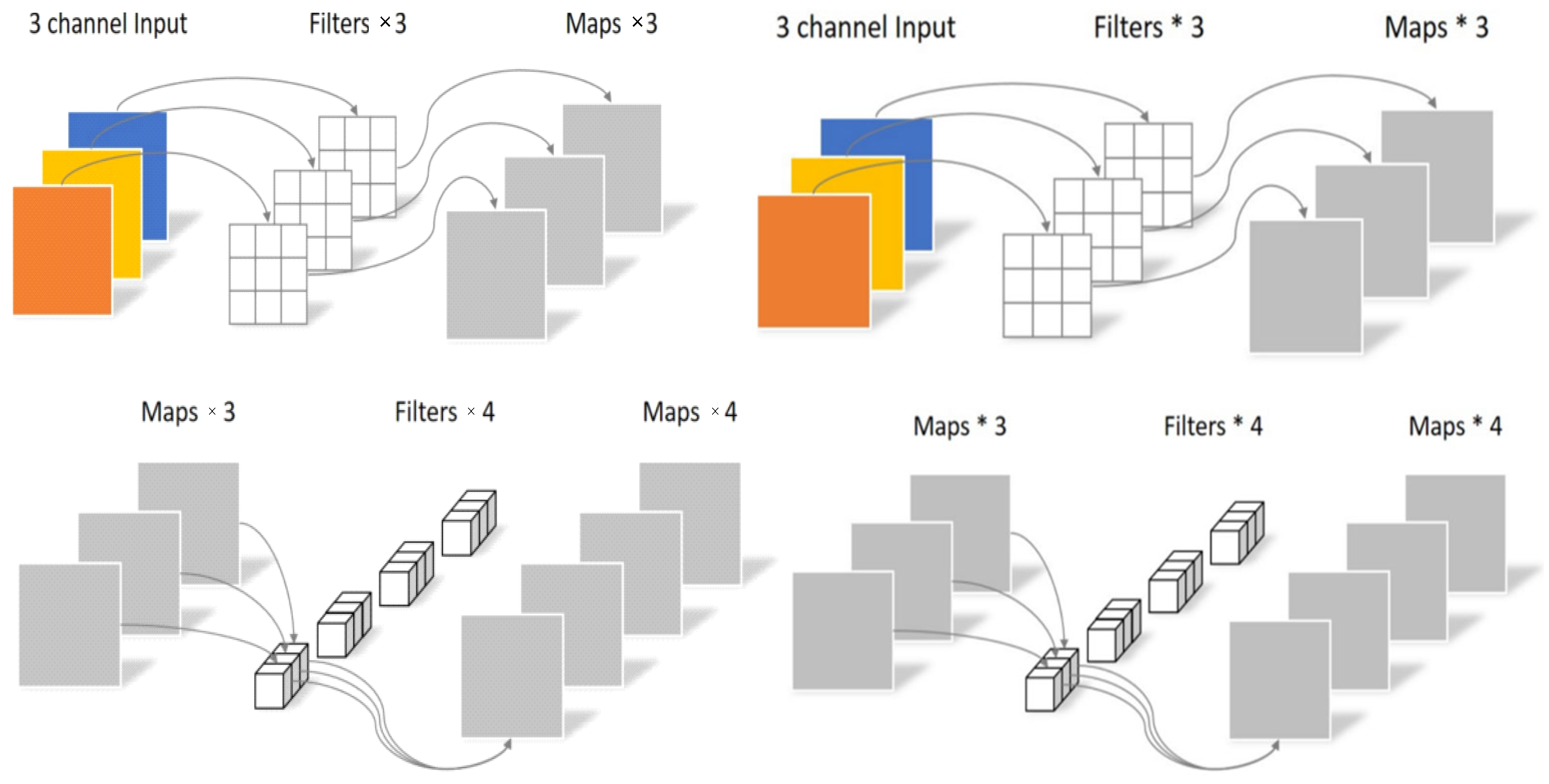

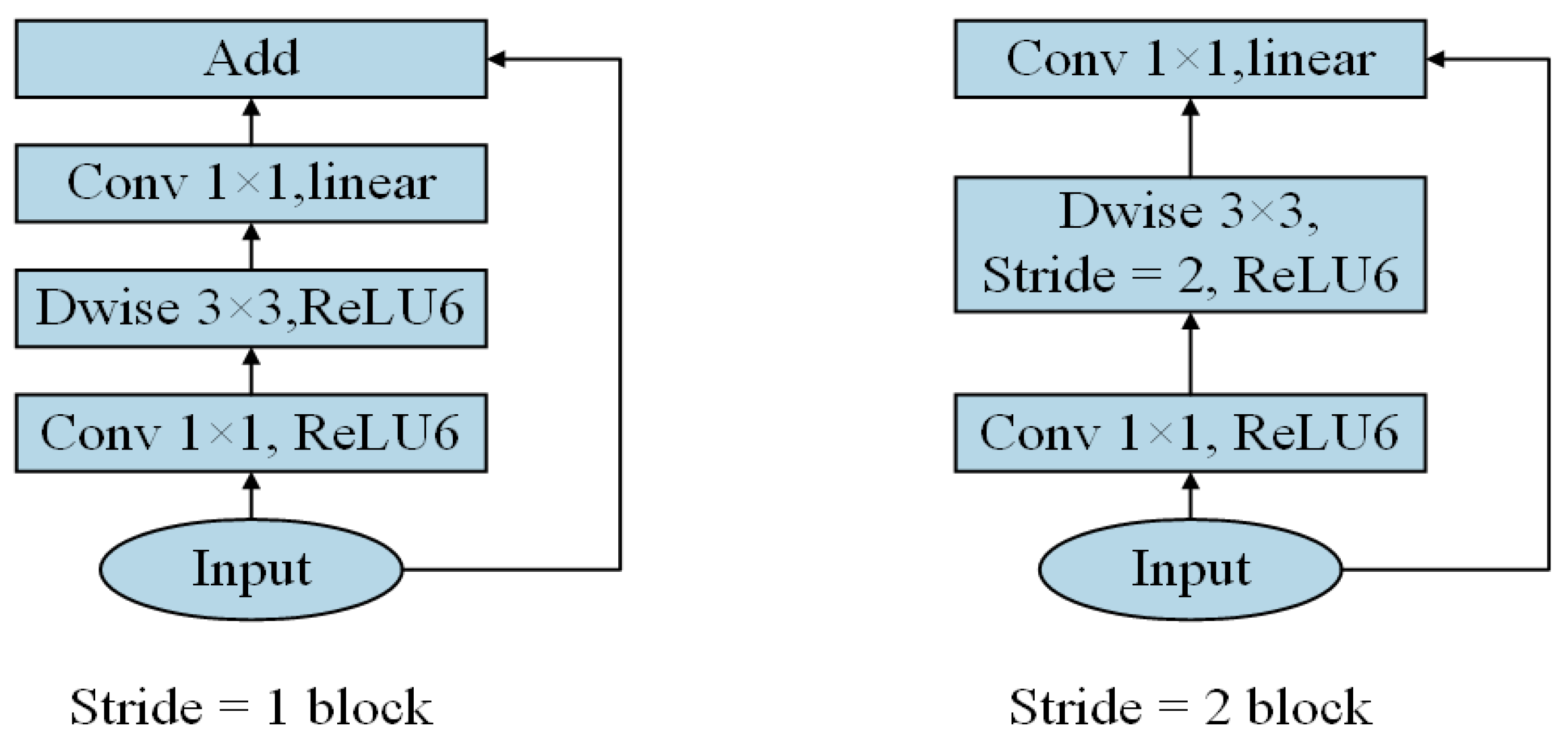

2.2.2. Classification Modelling Methods

2.3. Hyperspectral Image Preprocessing Methods and Model Construction

2.3.1. Spectral Signal Preprocessing

2.3.2. Classification Models and Optimisation Algorithms

One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network

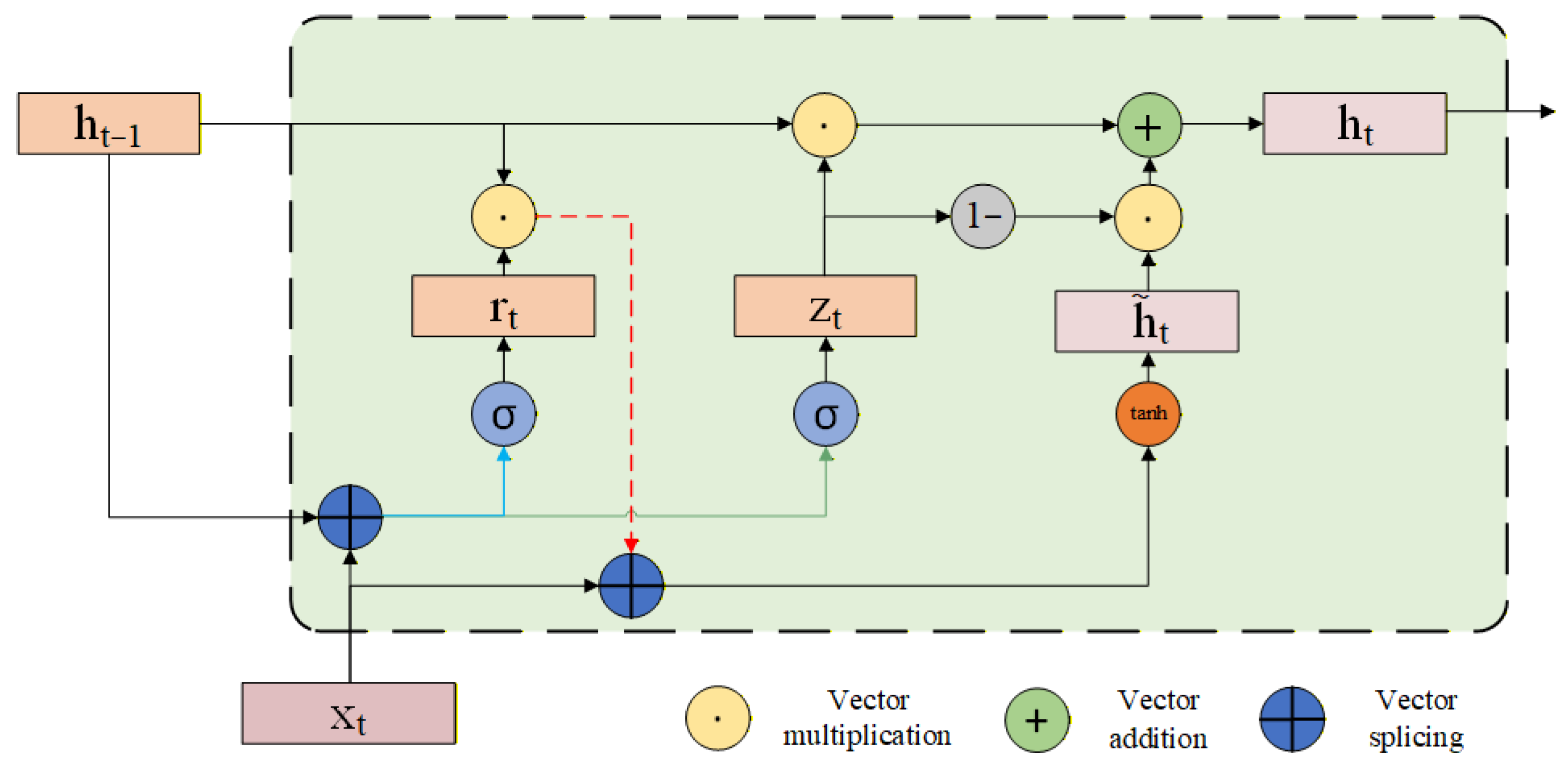

Gate Recurrent Unit

2.3.3. Newton-Raphson-Based Optimizer

2.3.4. Model Construction

2.4. Model Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. RGB Image Model Results

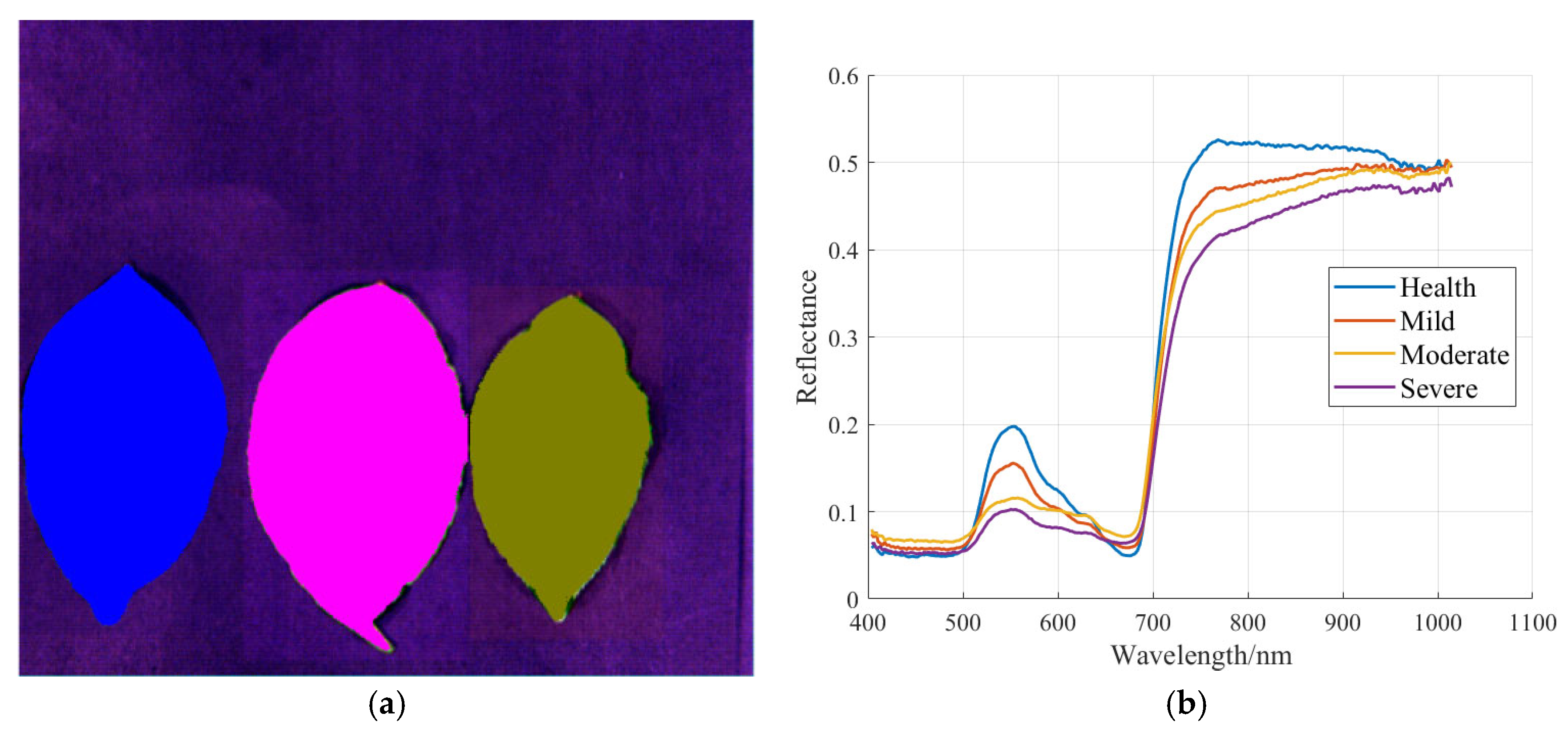

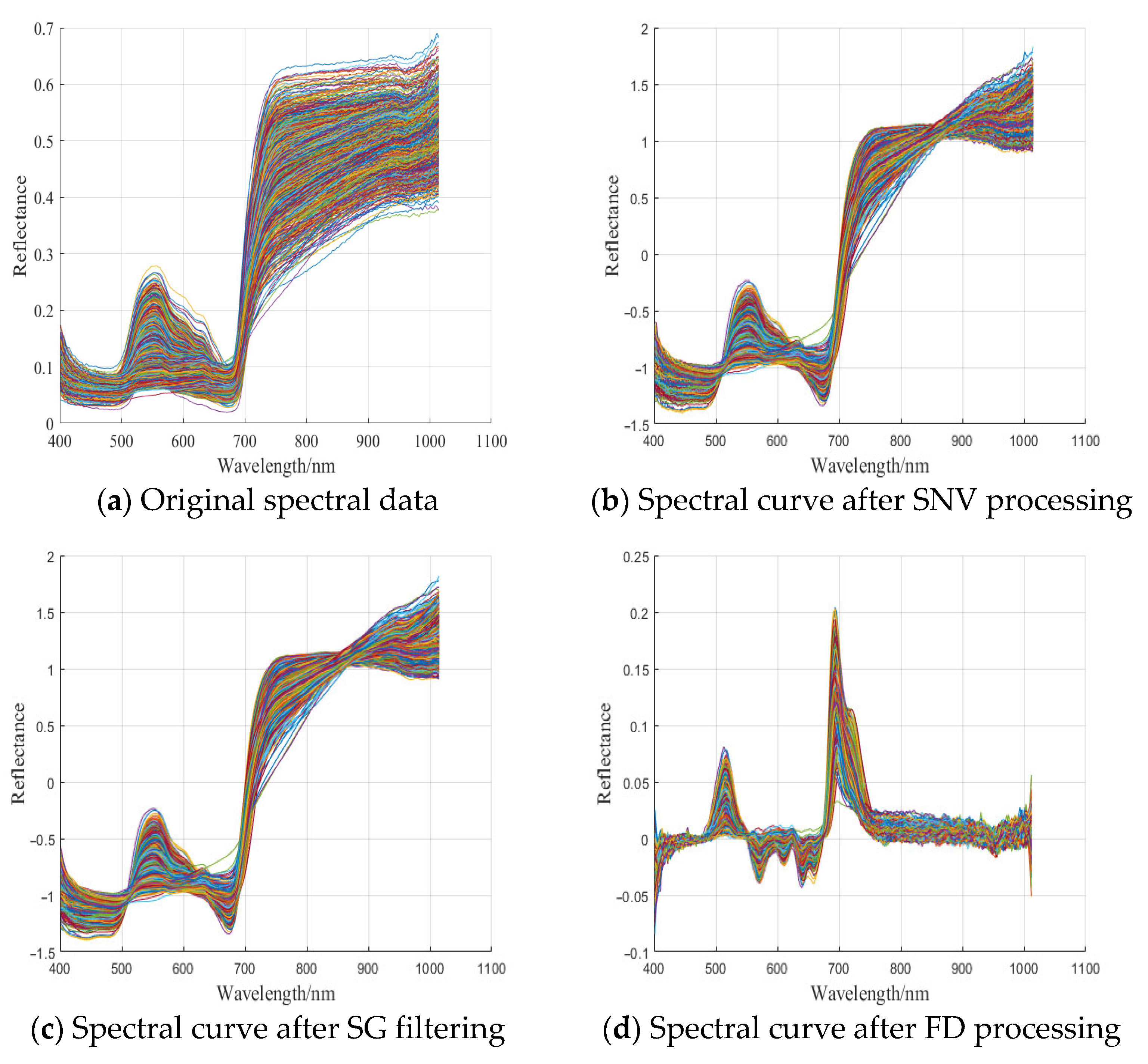

3.2. Sample Hyperspectral Curve and Pre-Processing Results

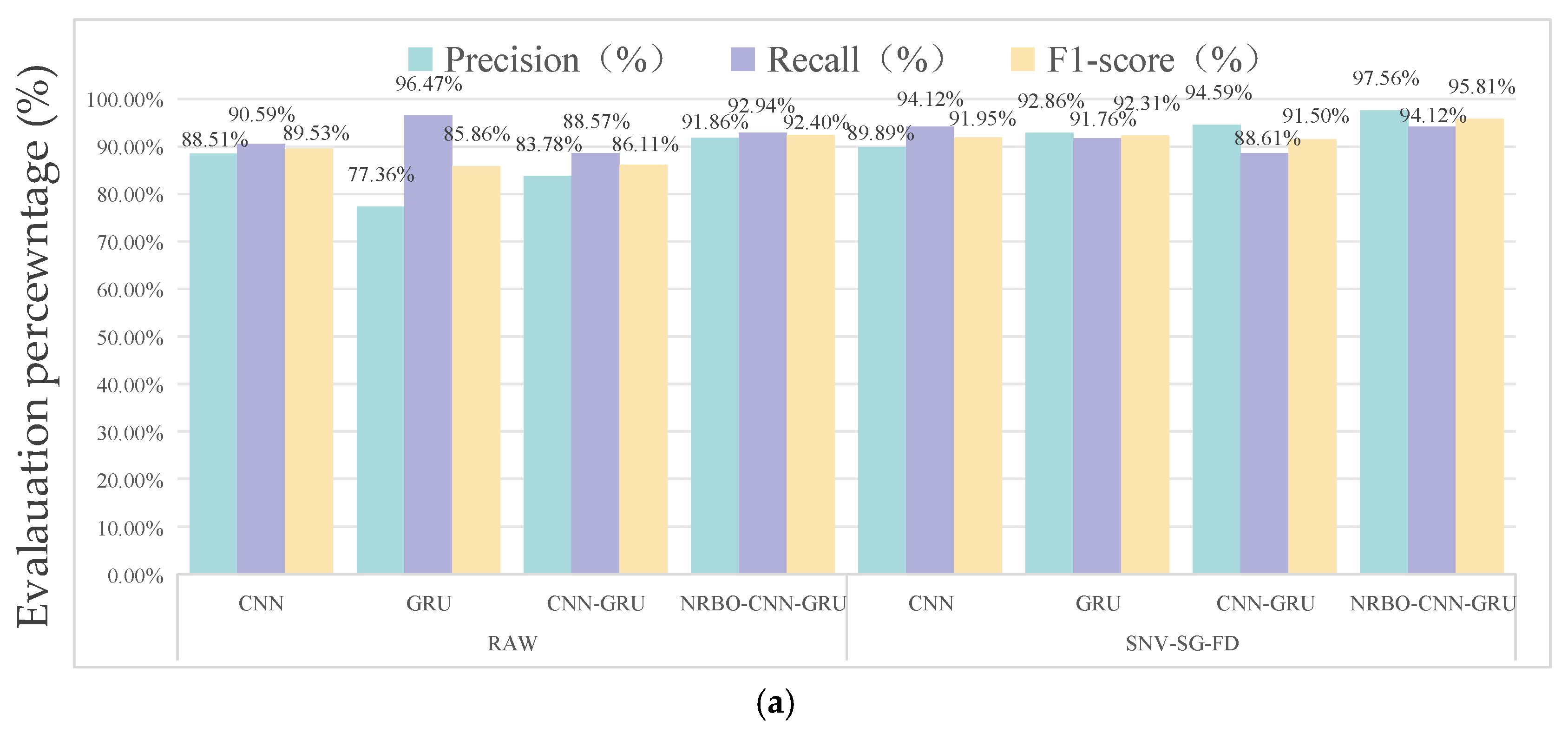

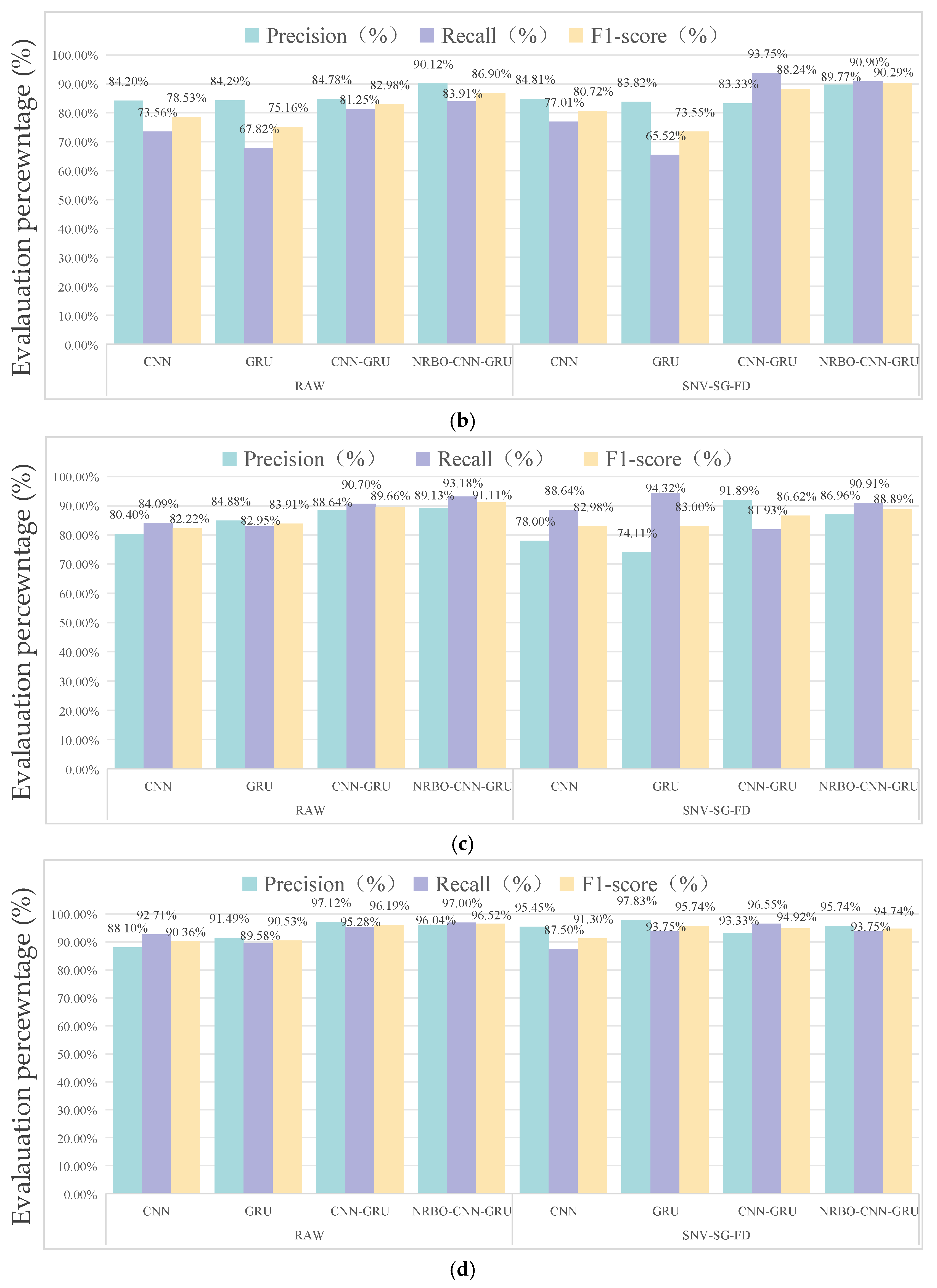

3.3. Performance Results of Different Network Models for Data Classification

3.4. Analysis of Model Validity

3.4.1. Comparison of Model Performance for Different Sample Categories

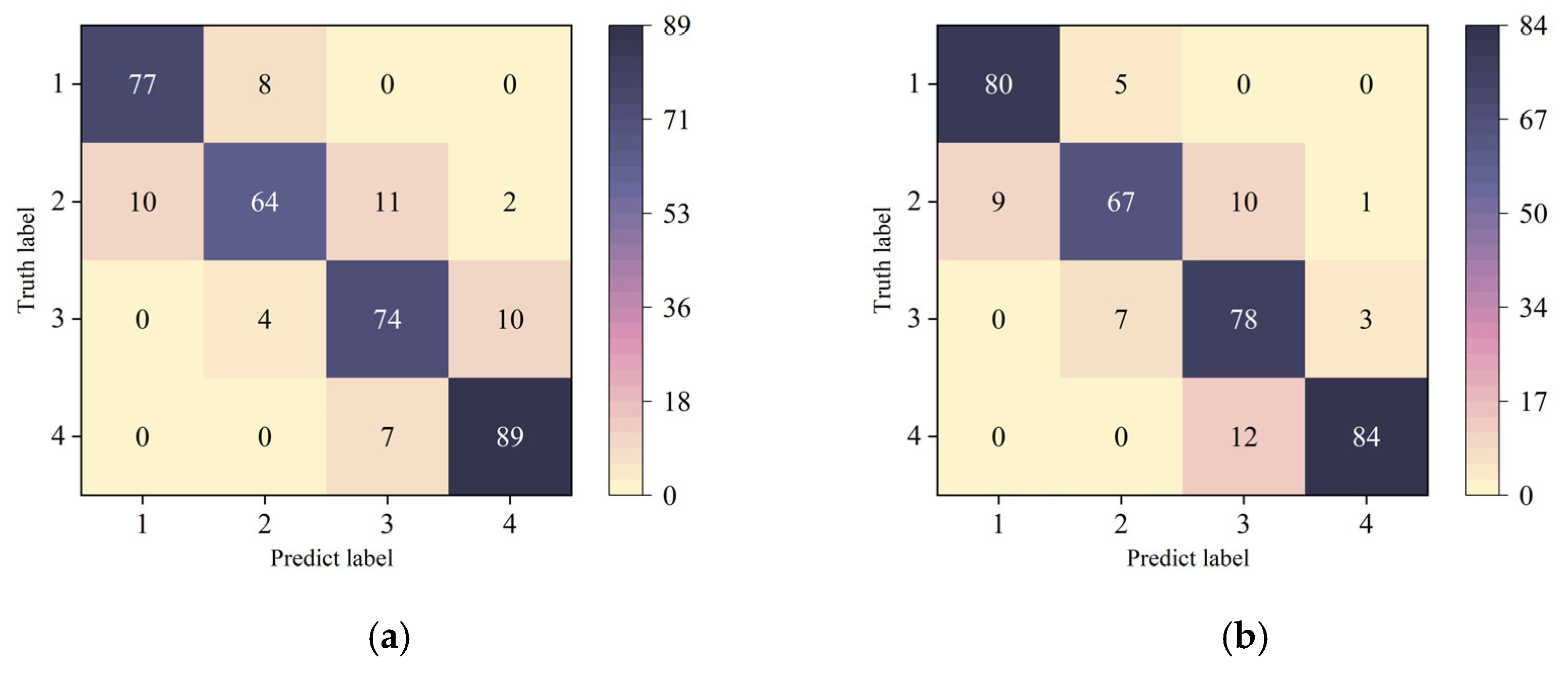

3.4.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Result Analysis

4.2. Challenges and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HSI | Hyperspectral Imaging | LRN | local response normalization |

| SG | Savitzky-Golay | GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| MSC | Multiplicative Scatter Correction | VGG | Visual Geometry Group |

| 1D-CNN | One-Dimensional Convolution Neural Network | RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit | NRSR | Newton-Raphson Search Rule |

| NRBO | Newton-Raphson-based optimizer | TAO | Trap Avoidance Operator |

| RF | Random Forest | ROI | Region of Interest |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machines | ILSVRC | ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge |

References

- Dong, Z.F.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y. Survey of the occurency and distribution of major disease and insect pest species of tea plants in Shangluo. J. Shanxi Agric. Univ. 2018, 38, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Yuan, D.; Guo, G.Y.; Yang, G.Y.; Ye, N.X. Identification of anthracnose pathogen in tea plant. J. South. Agric. 2017, 48, 448–453. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, W.Z. Investigation and research on Cercospora sp. J. Tea 1983, 1, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ponmurugan, P.; Manjukarunambika, K.; Gnanamangai, B.M. Impact of various foliar diseases on the biochemical, volatile and quality constituents of green and black teas. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2016, 45, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.N.; Lu, A.X.; Kun, J.R.; Wang, B.; Miao, Y.W.; Chen, Y.J.; Ho, C.T.; Meng, Q.; Tong, H.R. Characterization of triterpenoids as possible bitter-tasting compounds in teas infected with bird’s eye spot disease. Food Res. Int. 2023, 167, 112643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.N.; Miao, Y.W.; Zhou, J.Y.; Huang, R.; Dai, H.W.; Liu, M.; Lin, Y.Z.; Chen, Y.J.; Ho, C.T.; Tong, H.R.; et al. Sensory-directed isolation and identification of an intense salicin-like bitter compound in infected teas with bird’s eye spot disease. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.T.; Ren, Z.; Zhu, L.; Tang, X.M.; Fu, C.W.; Wang, Z.F.; Wang, X.Z.; Yi, K.; Hu, Y.J. Effects of soil conditioner and Bacillus subtilis fungicide on the growth and development of tobacco and diseases of tobacco. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2022, 50, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, S.; Zhang, B.R.; Zhang, D.H. Foresight from the hometown of green tea in china: Tea farmers’ adoption of pro-green control technology for tea plant pests. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.S.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, M.Z. Detection and severity analysis of tea leaf blight based on deep learning. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 90, 107023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trippa, D.; Scalenghe, R.; Basso, F.M.; Panno, S.; Davino, S.; Morone, C.; Giovino, A.; Oufensou, S.; Luchi, N.; Yousefi, S.; et al. Next-generation methods for early disease detection in crops. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2023, 80, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, C.P.; Menounos, B.; Viner, N.; Skiles, S.M.; Beffort, S.; Denouden, T.; Arriola, S.G.; White, R.; Heathfield, D. Bridging the gap between airborne and spaceborne imaging spectroscopy for mountain glacier surface property retrievals. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 299, 113849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; Gao, L. Visual tea leaf disease recognition using a convolutional neural network model. Symmetry 2019, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Cai, M.D.; Yi, X.M.; Wang, G.Y.; Mo, L.F.; Chola, M.; Kapapa, C. Sweetgum Leaf Spot Image Segmentation and Grading Detection Based on an Improved DeeplabV3+ Network. Forests 2023, 14, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xuan, C.Z.; Ma, Y.H.; Tang, Z.H.; Gao, X.Y. An efficient and precise dynamic neighbor graph network for crop mapping using unmanned aerial vehicle hyperspectral imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 230, 109838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.T.; Ma, B.X.; Wang, H.T.; Li, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.J.; Yu, G.W. Non-Destructive Detection of Different Pesticide Residues on the Surface of Hami Melon Classification Based on tHBA-ELM Algorithm and SWIR Hyperspectral Imaging. Foods 2023, 12, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Luo, Q.; Yang, L.; Gao, C.L.; Ling, C.J.; Wu, W.B. Research review on quality detection of fresh tea leaves based on spectral technology. Foods 2023, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.H.; Zhang, J.C.; Huang, Y.B.; Tian, Y.Y.; Yuan, L. Detection and discrimination of disease and insect stress of tea plants using hyperspectral imaging combined with wavelet analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 193, 106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.G.; Zhang, J.; Huang, S.Y.; Wang, J.P.; Yao, H.Y.; Song, Y.Y. Recognition of tea diseases under natural background based on particle swarm optimization algorithm optimized support vector machine. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 18th International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN), Warwick, UK, 20–23 July 2020; Volume 1, pp. 547–552. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.H.; Lin, X.R.; Chen, S.F. Application of hyperspectral imaging for identification of types and levels of pest damage on tea leaves. In Proceedings of the 2023 American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers Annual International Meeting, Omaha, NE, USA, 9–12 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.X.; Zhao, Y.R.; Bu, H.C.; Wu, X.Y. Oilseed Rape Sclerotinia in Hyperspectral Images Segmentation Method Based on Bi-GRU and Spatial-Spectral Information Fusion. Smart Agric. 2024, 6, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Saviolo, A.; Bonotto, M.; Evangelista, D.; Imperoli, M.; Lazzaro, J.; Menegatti, E.; Pretto, A. Learning to segment human body parts with synthetically trained deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Autonomous Systems, Wuhan, China, 14–16 May 2021; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 412, pp. 696–712. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Q.; Zhao, X.Y.; Xu, H.N.; Zhang, L.M.; Xie, B.Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, L.C.; Fan, D.C.; Li, L. An Interpretable High-Accuracy Method for Rice Disease Detection Based on Multisource Data and Transfer Learning. Plants 2023, 12, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Guo, Y.G.; Lu, X.B. Classification Method of UAV Remote Sensing ImageBased on Improved AlexNet Network. J. Hunan Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2023, 38, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.H.; Yan, L.J.; Zhao, X.H.; Yuan, L.; Jin, J.; Zhang, J.C. Detection and Discrimination of Tea Plant Stresses Based on Hyperspectral Imaging Technique at a Canopy Level. Phyton 2021, 90, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, Z.B.; Li, C.; Wu, J.; Yue, J. High performance vegetable classification from images based on AlexNet deep learning model. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, E.G. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.P.; Liu, Y.Y.; Shao, Z.E.; Huang, K.W. An improved VGG16 model for pneumonia image classification. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A.X.; Xiao, Y.C.; Li, D.C.; Xue, J.Y. Status Recognition of Magnetic Fluid Seal Based on High-Order Cumulant Image and VGG16. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 929795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Sheu, R.K.; Peng, W.Y.; Wu, H.J.; Tseng, C.H. Video-based parking occupancy detection for smart control system. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.T.; Jiang, D.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tao, B.; Kong, J.Y.; Tian, J.R.; Tong, X.L.; Xu, M.M.; Fang, Z.F. Real-Time Target Detection Method Based on Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 861286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.T.; Ding, L.Y.; Ji, J.T.; Jin, X.; Feng, Z.H.; Hao, M.C. Design and experiment of variable-spray system based on deep learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.H.; Wang, B.; Yang, J.Y.; Yin, F.; He, L.S. Research on Hyperspectral Inversion of Soil Organic Carbon in Agricultural Fields of the Southern Shaanxi Mountain Area. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.Q.; Zhong, N.; Zhou, Y.H.; Chen, S.B.; Dong, Z.B.; Qi, L.; Feng, X. Synergistic spectral-spatial fusion in hyperspectral Imaging: Dual attention-based rice seed varieties identification. Food Control 2025, 176, 111411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.W.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, D.; Shi, Y.B.; Shou, H.Y.; Li, M.X.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, C.X. Application of flash GC e-nose and FT-NIR combined with deep learning algorithm in preventing age fraud and quality evaluation of pericarpium citri reticulatae. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, X.X.; Li, S.K.; Du, G.R.; Jiang, L.W.; Liu, X.; Ding, S.H.; Shan, Y. A rapid and nondestructive approach for the classification of different-age citri reticulatae pericarpium using portable near infrared spectroscopy. Sensors 2020, 20, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z.C.; Hu, R.J.; She, B.; Pan, Z.G.; Zhou, X.G.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, D.Y. Hyperspectral and imagery integrated analysis for vegetable seed vigor detection. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2023, 131, 104605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Z.; Li, F.; Hu, Y.C.; Yu, K. NTRI: A novel spectral index for developing a precise nitrogen diagnosis model across pre- and post-anthesis stages of maize plants. Field Crop Res. 2025, 325, 109829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.K.; Yu, J.B. Gearbox Fault Diagnosis Based on One-dimension Residual Convolutional Auto-encoder. J. Mech. Eng. Chin. Ed. 2020, 56, 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Xie, X.G.; Sun, W.W.; Li, Y.M. Tool wear prediction model using multi-channel 1d convolutional neural network and temporal convolutional network. Lubricants 2024, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Xue, B.; Yang, M.Y.; Zhang, M.J.; Xu, Z.G.; Wang, J.Y.; Chen, S.L.; Liu, Y. Evolutionary neural architecture search for automatically designing CNN-GRU-Attention neural networks for turntable servo systems. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2025, 283, 127765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arathy, N.G.R.; Adarsh, S. Innovative knowledge-based system for streamflow hindcasting: A comparative assessment of Gaussian Process-Integrated Neural Network with LSTM and GRU models. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 188, 106433. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Lu, H.; Shi, R.J.; Fan, X.C.; Deng, Z.H. A novel fault diagnosis method for key transmission sections based on Nadam-optimized GRU neural network. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 233, 110522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.T.; Chen, W.H.; Liu, J.; Cheng, L.S.; Xia, M. Trustworthy and intelligent fault diagnosis with effective denoising and evidential stacked GRU neural network. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 35, 3523–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, R.; Manoharan, P.; Pradeep, J. Newton-Raphson-based optimizer: A new population-based metaheuristic algorithm for continuous optimization problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, M.J.; Bates, D.M. Newton—Raphson and EM Algorithms for Linear Mixed-Effects Models for Repeated-Measures Data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadianfar, I.; Bozorg-Haddad, O.; Chu, X. Gradient-based optimizer: A new metaheuristic optimization algorithm. Inf. Sci. 2020, 540, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Lu, F. Research on prediction of ash content in flotation-recovered clean coal based on nrbo-cnn-lstm. Minerals 2024, 14, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Y.; Hu, Q.H.; Liu, C.P.; Yang, J.W. Food image recognition based on transfer learning and batch normalization. Comput. Appl. Softw. 2021, 38, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Junges, A.H.; Marcus, A.K.A.; Thor, V.M.F.; Jorge, R.D. Leaf hyperspectral reflectance as a potential tool to detect diseases associated with vineyard decline. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2020, 45, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Dao, P.D.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Shang, J. Recent Advances of Hyperspectral Imaging Technology and Applications in Agriculture. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.Y.S.; Pan, N.; Lin, Z.Y.; Chen, X.T.; Wu, J.N.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Z.Y. Research Progress on the Vibrational Spectroscopy Technology in the Quality Detection of Fish Oil. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2025, 45, 301–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bouslihim, Y.; Bouasria, A. Potential of EnMAP Hyperspectral Imagery for Regional-Scale Soil Organic Matter Mapping. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.M.; Chen, A.; Yang, X.C.; Xing, X.Y. Estimation of crude protein content in natural pasture grass using unmanned aerial vehicle hyperspectral data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 109714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.C.; He, J.; Liu, G.; Li, W.L.; Li, Z.; Li, Z. Inversion analysis of soil nitrogen content using hyperspectral images with different preprocessing methods. Ecol. Inf. 2023, 78, 102381. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.Z.; Xu, S.H.; Teng, J.H.; Jiang, X.H.; Zhang, H.; Qin, Y.Z.; He, Y.S.; Fan, L. Deep learning assisted ATR-FTIR and Raman spectroscopy fusion technology for microplastic identification. Microchem. J. 2025, 212, 113224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H.Y.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Z.D.; Li, K.; Yu, Y.Q.; Li, Q. Improved Attention Mechanism MobileNetV2 Network for SERS Classification of Water Pollution. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2025, 62, 073004. [Google Scholar]

- Muzakka, K.; Sören, M.; Stefan, K.; Jan, E.; Alina, B.; Helene, H.; Sebastian, S.; Martin, F. Analysis of Rutherford backscattering spectra with CNN-GRU mixture density network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Cao, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, F.; Fan, S.; Yan, L.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, G.; Xu, B.; et al. Prediction of multi-task physicochemical indices based on hyperspectral imaging and analysis of the relationship between physicochemical composition and sensory quality of tea. Food Res. Int. 2025, 19, 116455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disease Level | Health | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion density | 0 | D ≤ 0.75 | 0.75 ≤ D ≤ 1.5 | D ≥ 1.5 |

| Sample quantity | 285 | 289 | 293 | 321 |

| Parameter | Set Value |

|---|---|

| MiniBatchSize | 128 |

| Range of L2 Regularization Coefficient | [1 × 10−4, 1 × 10−1] |

| Number of hidden nodes range | [10, 30] |

| Learning rate range | [1 × 10−3, 1 × 10−2] |

| Epoch | 100 |

| Maximum number of iterations | 10 |

| Modelling Methods | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlexNet | 63.48% | 63.77% | 64.23% | 63.75% |

| MobileNet-V2 | 79.26% | 79.15% | 78.95% | 78.73% |

| VGG16 | 65.73% | 71.50% | 65.18% | 65.99% |

| Ordinal Number | MSC | SNV | SG-FD | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 84.58% | |||

| 2 | √ | 85.74% | ||

| 3 | √ | 85.46% | ||

| 4 | √ | 85.91% | ||

| 5 | √ | √ | 85.17% | |

| 6 | √ | √ | 86.83% | |

| 7 | √ | √ | 84.66% | |

| 8 | √ | √ | √ | 84.86% |

| Datatypes | Modelling Methods | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAW | CNN | 85.25% | 85.30% | 85.24% | 85.16% |

| GRU | 84.24% | 84.51% | 84.21% | 83.87% | |

| CNN-GRU | 88.96% | 88.58% | 88.95% | 88.74% | |

| NRBO-CNN-GRU | 91.74% | 91.79% | 91.76% | 91.73% | |

| SNV-SG-FD | CNN | 86.83% | 87.04% | 86.82% | 86.74% |

| GRU | 86.36% | 87.16% | 86.34% | 86.15% | |

| CNN-GRU | 90.23% | 90.79% | 90.21% | 90.32% | |

| NRBO-CNN-GRU | 92.43% | 92.51% | 92.42% | 92.43% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, W.; Tang, T.; Duan, Y.; Qiu, W.; Duan, L.; Lv, J.; Zeng, Y.; Guo, J.; Luo, Y. Study on the Detection Model of Tea Red Scab Severity Class Using Hyperspectral Imaging Technology. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222372

Wu W, Tang T, Duan Y, Qiu W, Duan L, Lv J, Zeng Y, Guo J, Luo Y. Study on the Detection Model of Tea Red Scab Severity Class Using Hyperspectral Imaging Technology. Agriculture. 2025; 15(22):2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222372

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Weibin, Ting Tang, Yuxin Duan, Wenlong Qiu, Linhui Duan, Jinhong Lv, Yunfang Zeng, Jiacheng Guo, and Yuanqiang Luo. 2025. "Study on the Detection Model of Tea Red Scab Severity Class Using Hyperspectral Imaging Technology" Agriculture 15, no. 22: 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222372

APA StyleWu, W., Tang, T., Duan, Y., Qiu, W., Duan, L., Lv, J., Zeng, Y., Guo, J., & Luo, Y. (2025). Study on the Detection Model of Tea Red Scab Severity Class Using Hyperspectral Imaging Technology. Agriculture, 15(22), 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222372