Do Pastures Diversified with Native Wildflowers Benefit Honeybees (Apis mellifera)?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

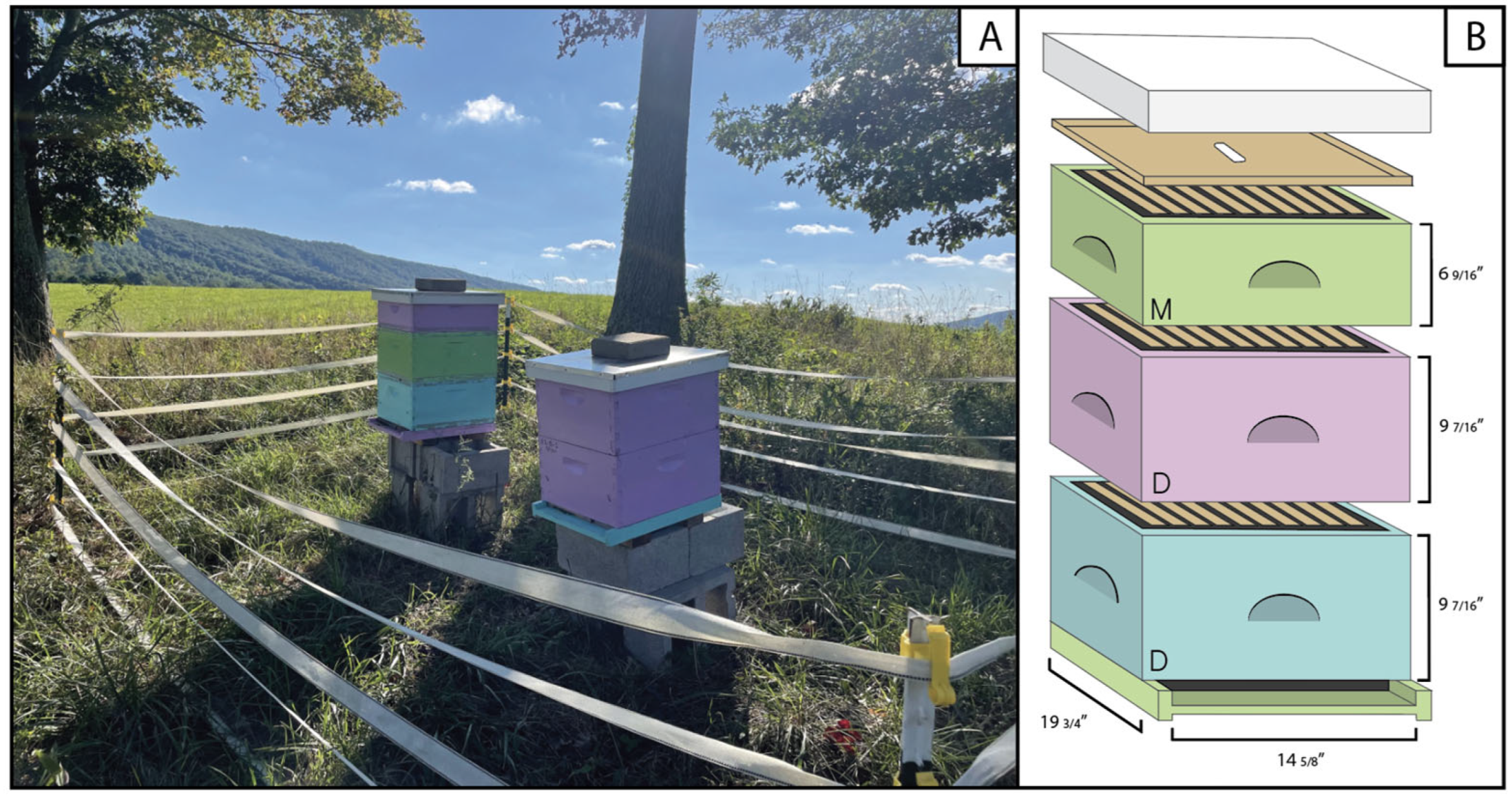

2.2. Hive Attributes

2.3. Pollen Analysis

2.4. In-Pasture Floral Resources

2.5. Pollinator Counts

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Hive Attributes

3.2. Pollen Analysis

3.3. Species-Level eDNA Indices

3.4. Pasture Floral Resources

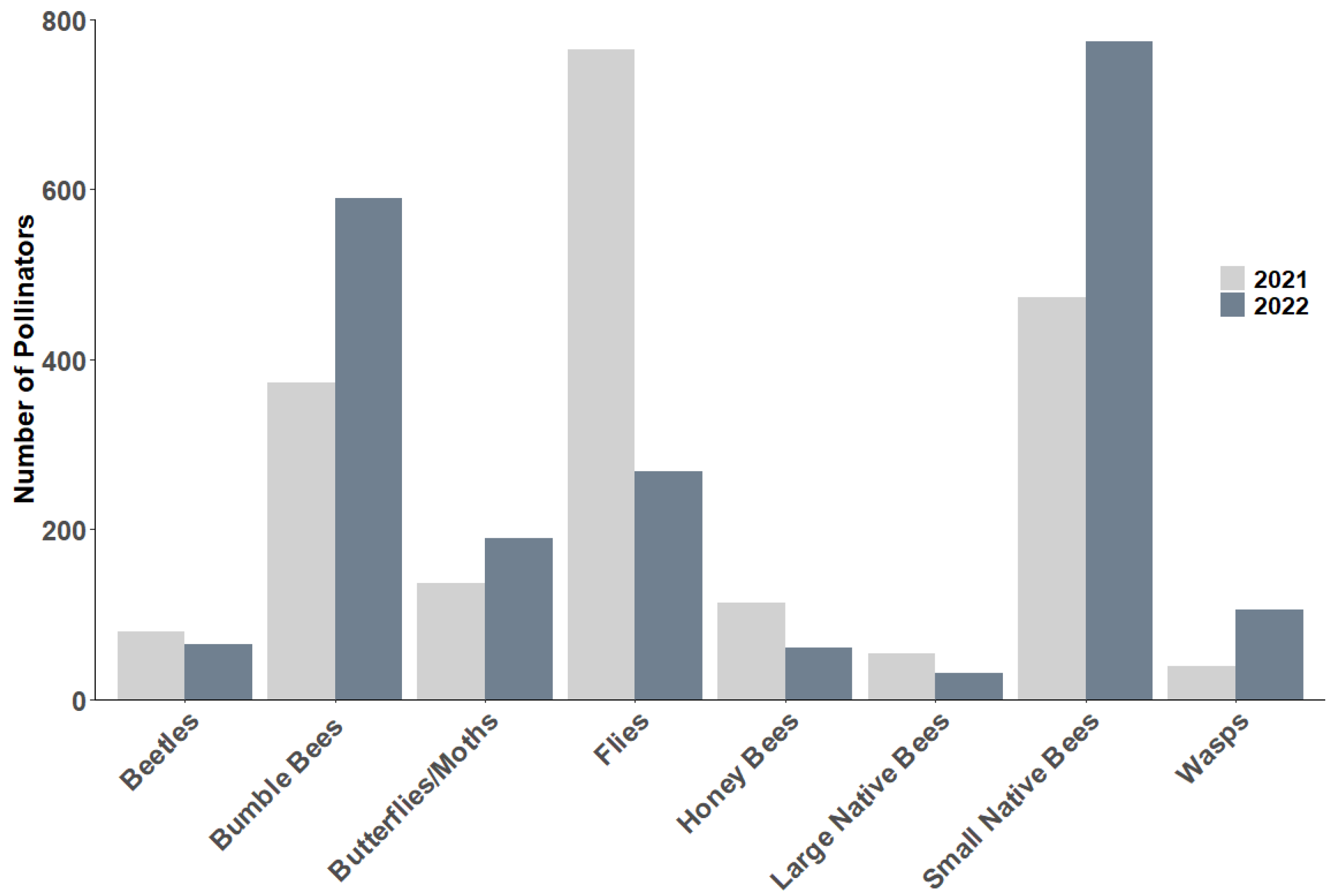

3.5. Pollinator Observations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sleper, D.A.; West, C.P. Tall Fescue. In Cool-Season Forage Grasses; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 471–502. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, C.W.; Porter, J.K.; Robbins, J.D.; Luttrell, E.S. Epichloë typhina from toxic tall fescue grasses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977, 34, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoveland, C.S. Importance and economic significance of the Acremonium endophytes to performance of animals and grass plant. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1993, 44, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoveland, C.S. Origin and History. In Tall Fescue for the Twenty-First Century; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lebuhn, G.; Droege, S.; Connor, E.F.; Gemmill-Herren, B.; Potts, S.G.; Minckley, R.L.; Griswold, T.; Jean, R.; Kula, E.; Roubik, D.W.; et al. Detecting insect pollinator declines on regional and global scales. Conserv. Biol. 2013, 27, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plascencia, M.; Philpott, S.M. Floral abundance, richness, and spatial distribution drive urban garden bee communities. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2017, 107, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renne, I.J.; Rios, B.G.; Fehmi, J.S.; Tracy, B.F. Low allelopathic potential of an invasive forage grass on native grassland plants: A cause for encouragement? Basic. Appl. Ecol. 2004, 5, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frances, A.L.; Reinhardt Adams, C.; Norcini, J.G. Importance of Seed and Microsite Limitation: Native Wildflower Establishment in Non-native Pasture. Restor. Ecol. 2010, 18, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, B.A.; Savage, J.; Bullock, J.M.; Nowakowski, M.; Orr, R.; Tallowin, J.R.B.; Pywell, R.F. Enhancing floral resources for pollinators in productive agricultural grasslands. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 171, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, F.; Tscharntke, T.; Bischoff, G.; Grass, I. Floral resource diversification promotes solitary bee reproduction and may offset insecticide effects—Evidence from a semi-field experiment. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaland, C.; Naisbit, R.E.; Bersier, L.F. Sown wildflower strips for insect conservation: A review. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2011, 4, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, E.-L.; Hyvönen, T.; Lindgren, S.; Kuussaari, M. Can pollination services, species diversity and conservation be simultaneously promoted by sown wildflower strips on farmland? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 179, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheper, J.; Bommarco, R.; Holzschuh, A.; Potts, S.G.; Riedinger, V.; Roberts, S.P.M.; Rundlöf, M.; Smith, H.G.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Wickens, J.B.; et al. Local and landscape-level floral resources explain effects of wildflower strips on wild bees across four European countries. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltham, H.; Park, K.; Minderman, J.; Goulson, D. Experimental evidence that wildflower strips increase pollinator visits to crops. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 3523–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noreika, N.; Bartomeus, I.; Winsa, M.; Bommarco, R.; Öckinger, E. Pollinator foraging flexibility mediates rapid plant-pollinator network restoration in semi-natural grasslands. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, W.; Dupont, Y.L.; Søegaard, K.; Eriksen, J. Optimizing yield and flower resources for pollinators in intensively managed multi-species grasslands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 302, 107062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shaara, H.F. The foraging behaviour of honey bees, Apis mellifera: A review. VeterináRní Med. íNa 2014, 59, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvillon, M.J.; Ratnieks, F.L.W. Environmental consultancy: Dancing bee bioindicators to evaluate landscape “health”. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, A.R. Honeybee Colony Weight as an Index of Honey Production and Nectar Flow: A Critical Evaluation. J. Appl. Ecol. 1977, 14, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaplane, K.; Van der Steen, J.; Guzman, E. Standard methods for estimating strength parameters of Apis mellifera colonies. J. Apic. Res. 2013, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.V.; Goblirsch, M.; McDermott, E.; Tarpy, D.R.; Spivak, M. Is the brood pattern within a honey bee colony a reliable indicator of queen quality? Insects 2019, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vanEngelsdorp, D.; Tarpy, D.R.; Lengerich, E.J.; Pettis, J.S. Idiopathic brood disease syndrome and queen events as precursors of colony mortality in migratory beekeeping operations in the eastern United States. Prev. Vet. Med. 2013, 108, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.; Danner, N.; Grimmer, G.; Ankenbrand, M.; von der Ohe, K.; von der Ohe, W.; Rost, S.; Härtel, S.; Steffan-Dewenter, I. Evaluating multiplexed next-generation sequencing as a method in palynology for mixed pollen samples. Plant Biol. 2015, 17, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.L.; de Vere, N.; Keller, A.; Richardson, R.T.; Gous, A.; Burgess, K.S.; Brosi, B.J. Pollen DNA barcoding: Current applications and future prospects. Genome 2016, 59, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMinn-Sauder, H.; Lin, C.-H.; Eaton, T.; Johnson, R. A comparison of springtime pollen and nectar foraging in honey bees kept in urban and agricultural environments. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 825137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponsler, D.B.; Johnson, R.M. Honeybee success predicted by landscape composition in Ohio, USA. PeerJ 2015, 3, e838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Le, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, F. SeqKit: A cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for fasta/q file manipulation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daubenmire, R.F. Canopy coverage method of vegetation analysis. Northwest Sci. 1959, 33, 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Garbuzov, M.; Ratnieks, F.L.W. Quantifying variation among garden plants in attractiveness to bees and other flower-visiting insects. Funct. Ecol. 2014, 28, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesmeijer, J.C.; Roberts, S.P.; Reemer, M.; Ohlemüller, R.; Edwards, M.; Peeters, T.; Schaffers, A.P.; Potts, S.G.; Kleukers, R.; Thomas, C.D.; et al. Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science 2006, 313, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretagnolle, V.; Gaba, S. Weeds for bees? A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, A.L.S.; Zhang, G.; Dolezal, A.G.; O’Neal, M.E.; Toth, A.L. Diversified farming in a monoculture landscape: Effects on honey bee health and wild bee communities. Environ. Entomol. 2020, 49, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcom, R. Honey Bee Colony Resource Acquisition, Population Growth, and Pollen Foraging in Diversified Native Grass-Wildflower Grazing System. Master’s Thesis, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Woodard, S.H.; Jha, S. Wild bee nutritional ecology: Predicting pollinator population dynamics, movement, and services from floral resources. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2017, 21, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoan, R.E.; O’Connor, L.D.; Starks, P.T. Seasonality of honeybee (Apis mellifera) micronutrient supplementation and environmental limitation. J. Insect Physiol. 2018, 107, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolezal, A.G.; Toth, A.L. Feedbacks between nutrition and disease in honeybee health. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 26, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchling, S.; Kopacka, I.; Kalcher-Sommersguter, E.; Schwarz, M.; Crailsheim, K.; Brodschneider, R. Investigating the role of landscape composition on honeybee colony winter mortality: A long-term analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.K.; Seeley, T.D. Foraging strategy of honeybee colonies in a temperate deciduous forest. Ecology 1982, 63, 1790–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekman, M.; Ratnieks, F.L.W. Long-range foraging by the honeybee, Apis mellifera L. Funct. Ecol. 2000, 14, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Murray, C.J.; Clair, A.L.S.; Cass, R.P.; Dolezal, A.G.; Schulte, L.A.; Toth, A.L.; O’Neal, M.E. Native vegetation embedded in landscapes dominated by corn and soybean improves honey bee health and productivity. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 60, 1032–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulston, T.a.H.; Cane, J.H.; Buchmann, S.L. What governs protein content of pollen: Pollinator preferences, pollen–pistil interactions, or phylogeny? Ecol. Monogr. 2000, 70, 617–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.M.; Awmack, C.S.; Murray, D.A.; Williams, I.H. Are honeybees’ foraging preferences affected by pollen amino acid composition? Ecol. Entomol. 2003, 28, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, F.P.; Brunet, J. Honeybees exhibit greater patch fidelity than bumble bees when foraging in a common environment. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Jeon, H.; Jung, C. Foraging behaviour and preference of pollen sources by honeybee (Apis mellifera) relative to protein contents. J. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 44, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, G.M.; Milbrath, M.O.; Otto, C.R.V.; Isaacs, R. Honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies benefit from grassland/pasture while bumble bee (Bombus impatiens) colonies in the same landscapes benefit from non-corn/soybean cropland. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuell, J.K.; Fiedler, A.K.; Landis, D.; Isaacs, R. Visitation by wild and managed bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) to eastern U.S. native plants for use in conservation programs. Environ. Entomol. 2008, 37, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Clair, A.L.S.; Dolezal, A.G.; Toth, A.L.; O’Neal, M.E. North American prairie is a source of pollen for managed honeybees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J. Insect Sci. 2021, 21, ieab001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morandin, L.A.; Kremen, C. Bee preference for native versus exotic plants in restored agricultural hedgerows. Restor. Ecol. 2013, 21, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warzecha, D.; Diekötter, T.; Wolters, V.; Jauker, F. Attractiveness of wildflower mixtures for wild bees and hoverflies depends on some key plant species. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2018, 11, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabors, A.; Hung, K.-L.J.; Corkidi, L.; Bethke, J.A. California native perennials attract greater native pollinator abundance and diversity than nonnative, commercially available ornamentals in southern California. Environ. Entomol. 2022, 51, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Elevation (m) | Hectares | Dominant Soil | Planting Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diversified | 310 | 1.8 | Minnieville Loam | 5 June 2020 |

| Diversified | 827 | 1.9 | Chester-Glenelg Loam | 6 June 2020 |

| Diversified | 810 | 2 | Chester-Glenelg Loam | 7 June 2020 |

| Diversified | 426 | 2.6 | Braddock Fine Sandy Loam | 8 June 2020 |

| Diversified | 1174 | 4.3 | Tate Loam | 20 May 2020 |

| Conventional | 772 | 6.7 | Pigeonroost Loam | - |

| Conventional | 765 | 4.3 | Tate Loam | - |

| Conventional | 555 | 4 | Nicelytown Tilt Loam | - |

| Conventional | 682 | 4 | Frederick Gravelly Silt Loam | |

| Conventional | 682 | 4 | Frederick Gravelly Silt Loam |

| Scientific Name | Common Name | Mix Proportion | kg/ha Seeding Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andropogon gerardii | Big Bluestem | 0.32 | 3.59 |

| Schizachyrium scoparium | Little Bluestem | 0.20 | 2.24 |

| Sorghastrum nutans | Indian Grass | 0.30 | 3.36 |

| Coreopsis lanceolata | Lance Leaved Coreopsis | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| Linum perenne | Blue Flax | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| Tradescantia ohiensis | Ohio Spiderwort | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Rudbeckia hirta | Blackeyed Susan | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Echinacea purpurea | Purple Coneflower | 0.04 | 0.45 |

| Agastache foeniculum | Lavender Hyssop | 0.003 | 0.03 |

| Ratibida pinnata | Gray-headed Coneflower | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Helianthus maximiliani | Maximillian Sunflower | 0.03 | 0.34 |

| Solidago rigida | Rigid Goldenrod | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Gaillardia pulchella | Indian Blanket | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| 2021 | 2022 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diversified | Conventional | p-Value | Diversified | Conventional | p-Value | |

| Eggs (cm2) | 4606 | 3603 | 0.004 | 2736 | 3647 | 0.05 |

| Larvae (cm2) | 4820 | 4066 | 0.06 | 2521 | 3258 | 0.78 |

| Capped Brood (cm2) | 11,956 | 9929 | 0.06 | 6478 | 7812 | 0.91 |

| Honey (cm2) | 21,925 | 24,706 | 0.26 | 28,041 | 26,087 | 0.91 |

| Nectar (cm2) | 10,758 | 8373 | 0.07 | 8395 | 7919 | 0.75 |

| Pollen (cm2) | 8539 | 9060 | 0.59 | 5209 | 5426 | 0.73 |

| Genus Species | Diversified | Conventional |

|---|---|---|

| Cichorium intybus | TR | TR |

| Brassica juncea | - | 0.045 |

| Daucus carota | TR | 0.003 |

| Centaurea nigra | 0.034 | - |

| Coreopsis lanceolata * | 0.001 | TR |

| Gaillardia pulchella * | 0.022 | 0.002 |

| Erigeron annuus | TR | TR |

| Erigeron philadelphicus | TR | TR |

| Hypericum nitidum | - | 0.040 |

| Nyssa sylvatica | - | 0.051 |

| Plantago lanceolata | 0.109 | 0.055 |

| Plantago major | 0.039 | - |

| Rosa rubus | 0.053 | 0.059 |

| Rubus perrobustus | - | 0.048 |

| Solanum carolinense | TR | 0.001 |

| Rudbeckia hirta * | 0.001 | TR |

| Solidago canadensis | 0.030 | 0.000 |

| Solidago juncea | 0.042 | 0.117 |

| Symphyotrichum novae-angliae | 0.078 | 0.143 |

| Taraxacum officinale | TR | TR |

| Toxicodendron radicans | 0.104 | - |

| Trifolium pratense | 0.030 | - |

| Trifolium repens | 0.408 | 0.368 |

| Verbascum thapsus | 0.052 | 0.065 |

| Conventional | Diversified | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus Species | June | July | August | Mean | June | July | August | Mean |

| Agastache foeniculum * | - | - | - | - | 0 | 1.29 | 0.47 | 0.59 |

| Coreopsis lanceolata * | - | - | - | - | 2.28 | 0.27 | 0.53 | 1.03 |

| Coreopsis tinctoria * | - | - | - | - | 0 | 0.53 | 0 | 0.18 |

| Desmodium canadense * | - | - | - | - | 0 | 2.2 | 1.87 | 1.36 |

| Echinacea purpurea * | - | - | - | - | 0.33 | 0.39 | 1.04 | 0.59 |

| Gaillardia pulchella * | - | - | - | - | 1.01 | 0.53 | 1.33 | 0.96 |

| Helianthus maximiliani * | - | - | - | - | 0 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.4 |

| Heliopsis helianthoides * | - | - | - | - | 0 | 1.55 | 1.04 | 0.86 |

| Linum perenne * | - | - | - | - | 2.13 | 0 | 0.27 | 0.8 |

| Monarda fistulosis * | - | - | - | - | 0 | 2.83 | 3.6 | 2.14 |

| Ratibida pinnata * | - | - | - | - | 0 | 1.88 | 2.05 | 1.31 |

| Rudbeckia hirta * | - | - | - | - | 0.61 | 2.66 | 1.72 | 1.66 |

| Bellis perennis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.33 | 1.92 | 0 | 0 | 0.64 |

| Calystegia sepium | - | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.13 |

| Chamaecrista fasciculata | - | - | - | - | 0 | 3.07 | 1.47 | 1.51 |

| Cichorium intybus | 1.17 | 1.33 | 0.33 | 0.94 | 0 | 0 | 0.67 | 0.22 |

| Daucus carota | 0 | 0 | 0.67 | 0.22 | 0 | 0 | 0.88 | 0.29 |

| Desmodium paniculatum | - | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | 3.29 | 1.1 |

| Diodia virginiana | - | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | 3.73 | 1.24 |

| Erigeron spp. | - | - | - | - | 1.04 | 24 | 5.42 | 10.15 |

| Plantago lanceolata | 0.58 | 1.28 | 0.56 | 0.81 | - | - | - | - |

| Plantago major | 0 | 0 | 1.08 | 0.36 | - | - | - | - |

| Polygonum spp. | 0 | 0.5 | 1.78 | 0.76 | - | - | - | - |

| Solanum carolinense | 0.33 | 0.92 | 0.56 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.27 | 0.09 |

| Sisymbrium officinale | 0 | 4.67 | 0 | 1.56 | - | - | - | - |

| Taraxacum officinale | 0.33 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 | - | - | - | - |

| Trifolium pratense | 0.41 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 1.49 | 1.05 | 0.48 | 1.01 |

| Trifolium repens | 0.76 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 1.09 | 1.73 | 1.65 | 0.37 | 1.25 |

| Verbena urticifolia | - | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2.67 |

| Totals | 7.3 | 32.2 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Larcom, R.; Kietzman, P.; O’Rourke, M.; Tracy, B. Do Pastures Diversified with Native Wildflowers Benefit Honeybees (Apis mellifera)? Agriculture 2025, 15, 1924. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181924

Larcom R, Kietzman P, O’Rourke M, Tracy B. Do Pastures Diversified with Native Wildflowers Benefit Honeybees (Apis mellifera)? Agriculture. 2025; 15(18):1924. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181924

Chicago/Turabian StyleLarcom, Raven, Parry Kietzman, Megan O’Rourke, and Benjamin Tracy. 2025. "Do Pastures Diversified with Native Wildflowers Benefit Honeybees (Apis mellifera)?" Agriculture 15, no. 18: 1924. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181924

APA StyleLarcom, R., Kietzman, P., O’Rourke, M., & Tracy, B. (2025). Do Pastures Diversified with Native Wildflowers Benefit Honeybees (Apis mellifera)? Agriculture, 15(18), 1924. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181924