The Interplay of Pro-Innovative Behavior, Trust, and Farm Viability for Sustainability in the United Winemaking Agricultural Cooperative of Samos †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Concepts and Measurement

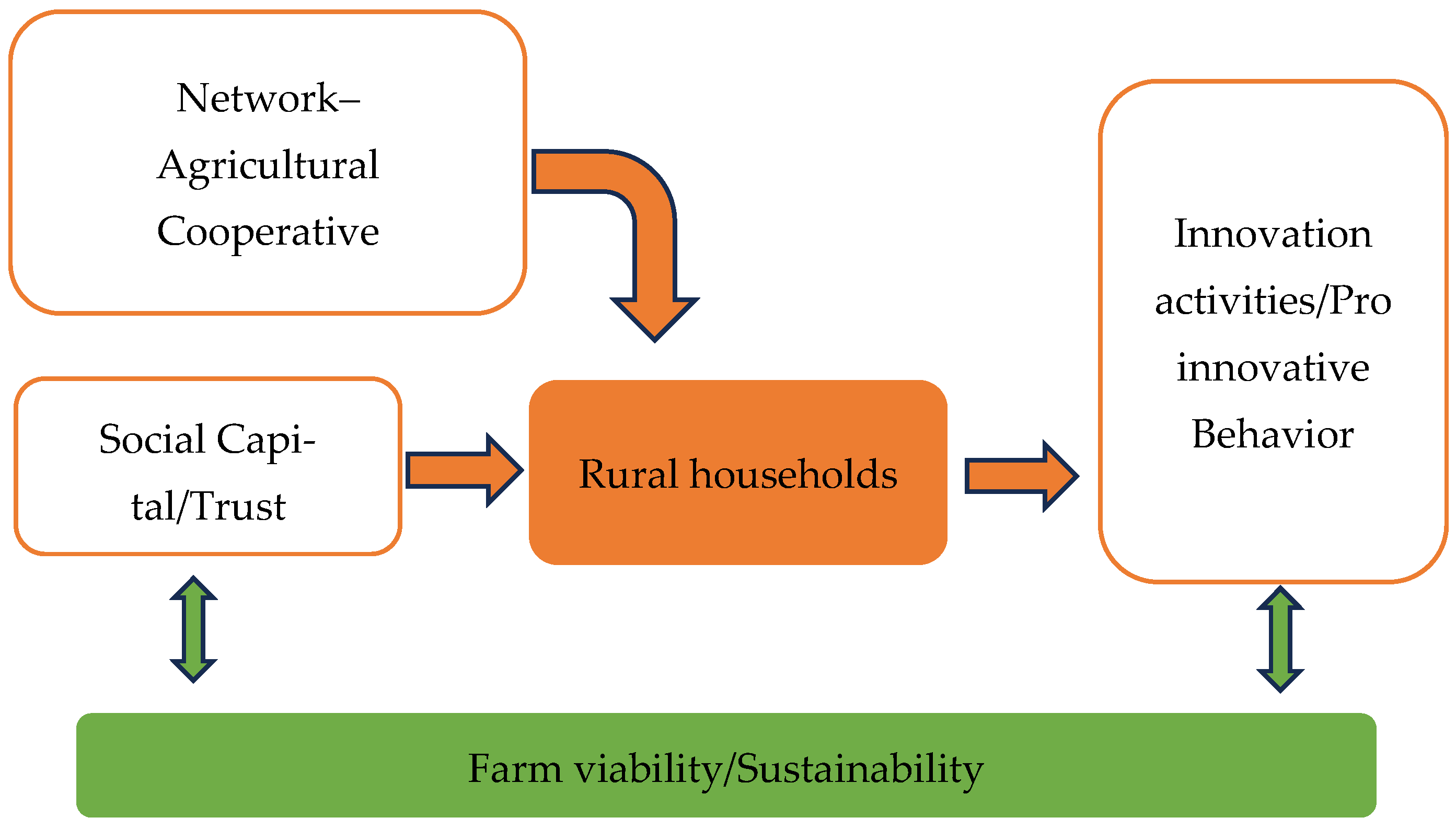

3. Theoretical Framework: Interdependencies and Linkages

3.1. Research Questions

3.2. Paper Structure

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Approach and Analysis

- (i)

- A preliminary desk survey was carried out to collect general information on the case study network involving different actors related to it. The result is a database including contact details with key employees and members of the network.

- (ii)

- For the research needs, a questionnaire was prepared, including both quantitative and qualitative items. The questionnaire comprised the following sections: (a) open-ended questions for innovation in their farms and in the cooperative; (b) personal/demographic data of the interviewee; and (c) social and economic aspects such as employment and income.

- (iii)

- Actors from the preliminary desk survey, by using snowball sampling, were selected for an online survey with the use of a semi-structured questionnaire due to pandemic COVID-19 impacts to travel permissions.

- (iv)

- Personal in-depth interviews were conducted with the producers and different actors of the network cooperative in order to collect mostly qualitative data to understand the relationship between the concepts of this study and the existing situation.

- (v)

- Quantitative data were analyzed to measure innovation, trust and economic viability by selecting appropriate variables and indexes. The qualitative data were used and referred analytically in order to describe and justify the quantitative data.

- K-DOC: Kaufman’s Domains of Creativity Scale;

- GRiPS: General Risk-Taking Propensity;

- PCI: Proactive Coping Inventory.

- ST: social trust;

- IT: institutional trust;

- FSN: formal social networks.

- MO: main occupation;

- WF: workers on the farm;

- FM: number of family members;

- YF: years in farming;

- SF: satisfaction from farming;

- I: income from farming;

- FP: farm profitability.

4.2. The Case Study Context

4.2.1. The Samos Island Viticultural Landscape

4.2.2. The UWC SAMOS Cooperative

Justification of the Case Study

4.2.3. Research Context and Participant Selection

5. Results

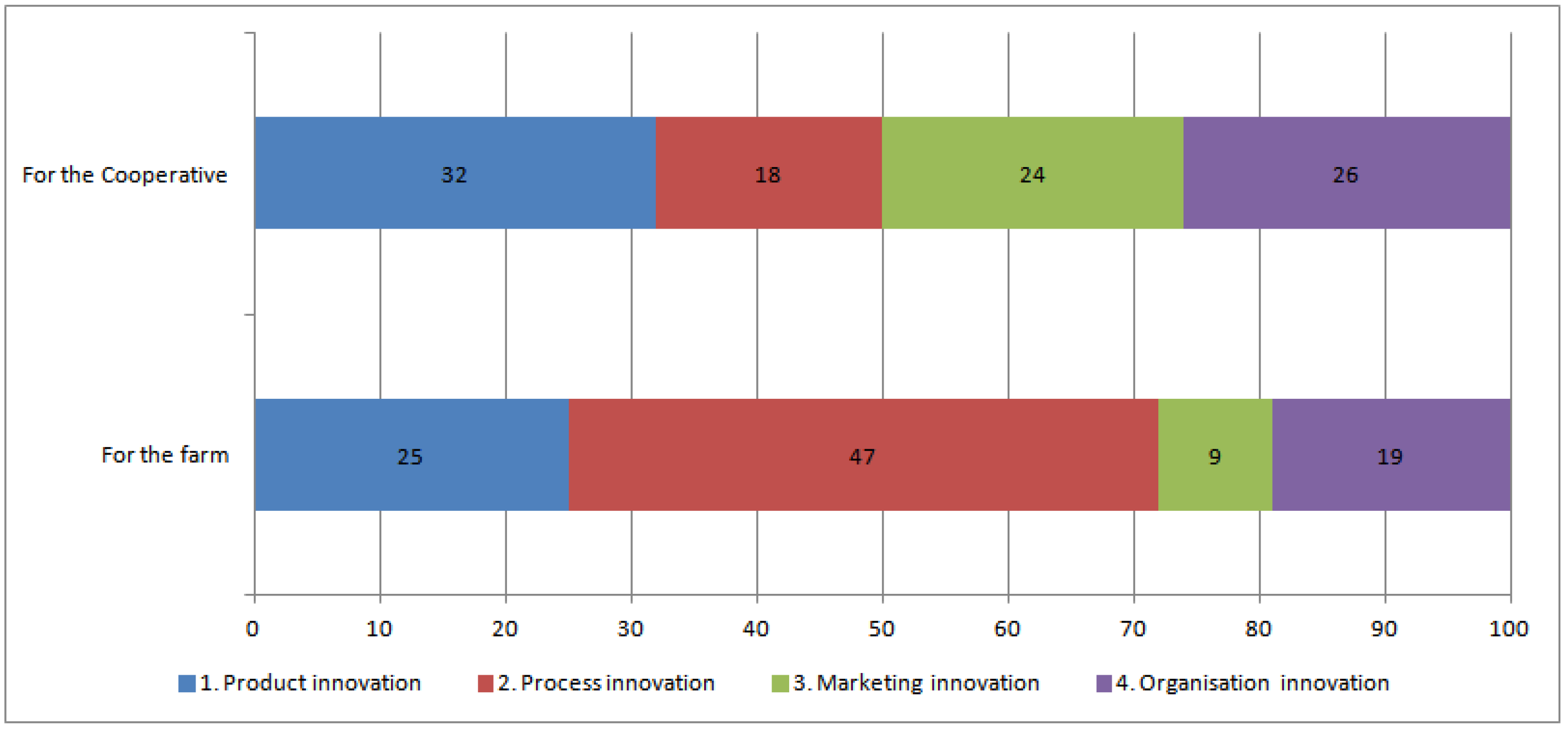

5.1. Types of Innovation

“There is nothing new to do with the vineyard. It is a method that we have learned from our grandfathers.”

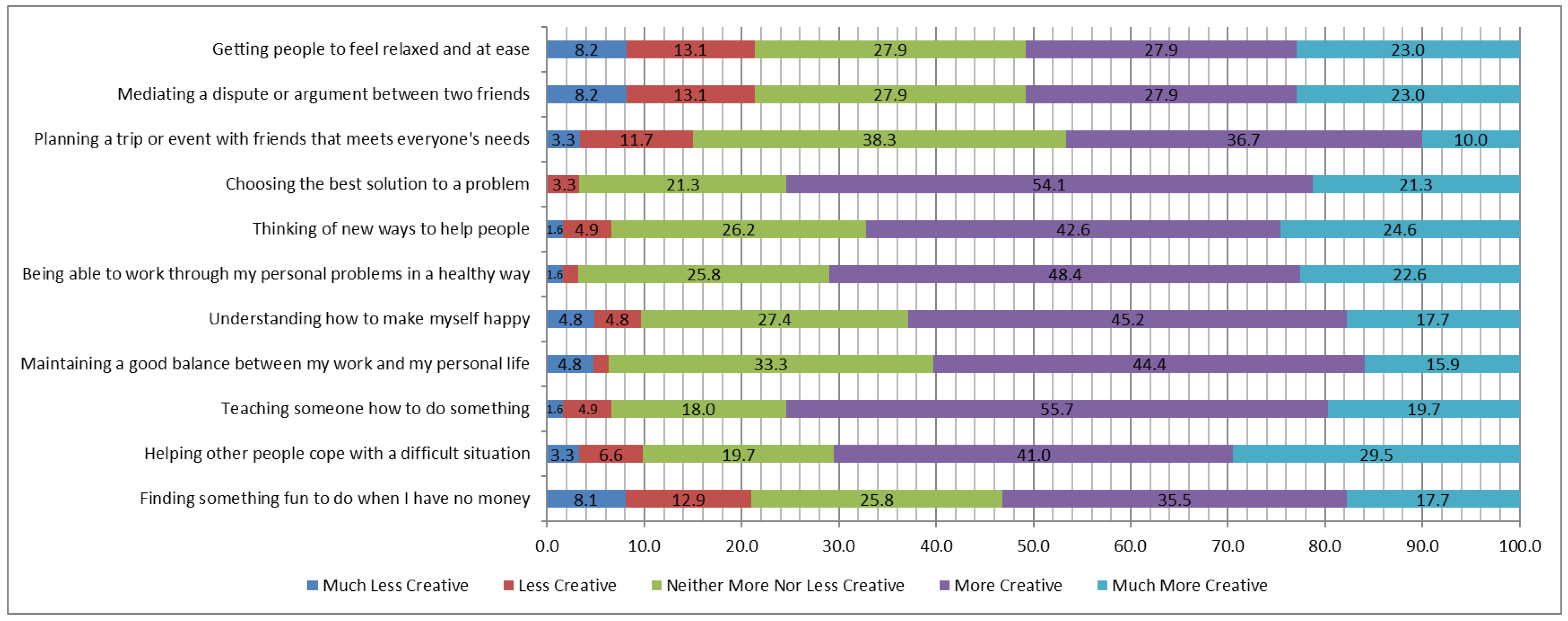

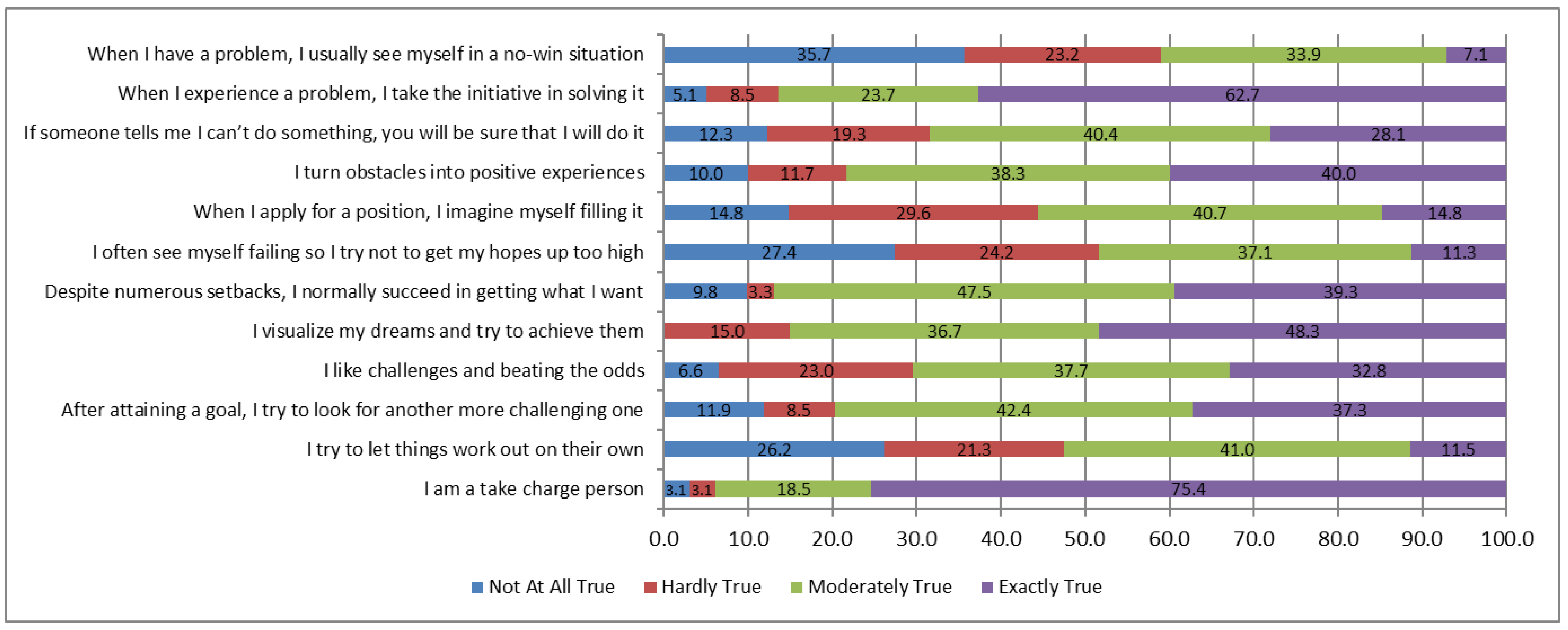

5.2. Pro-Innovative Behavior

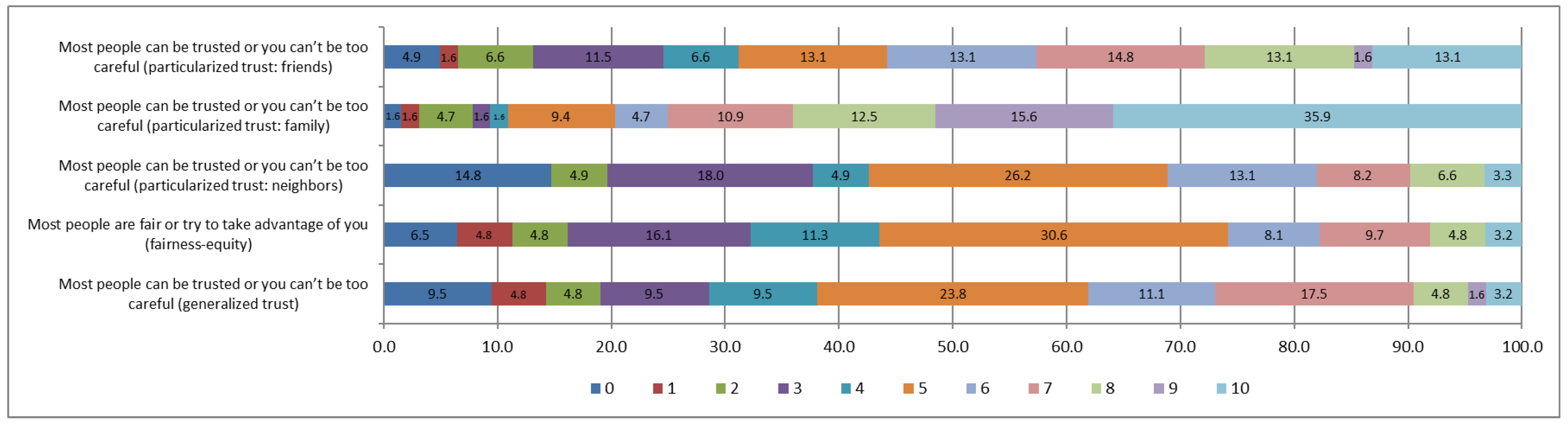

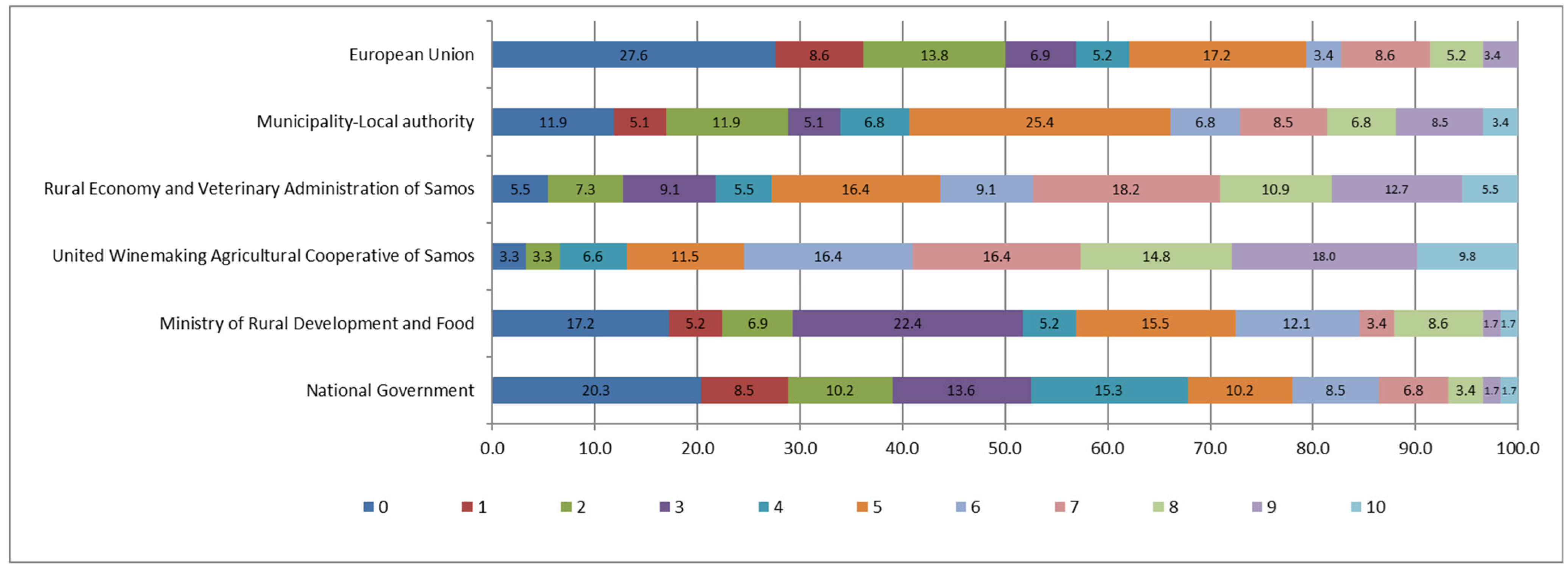

5.3. Trust

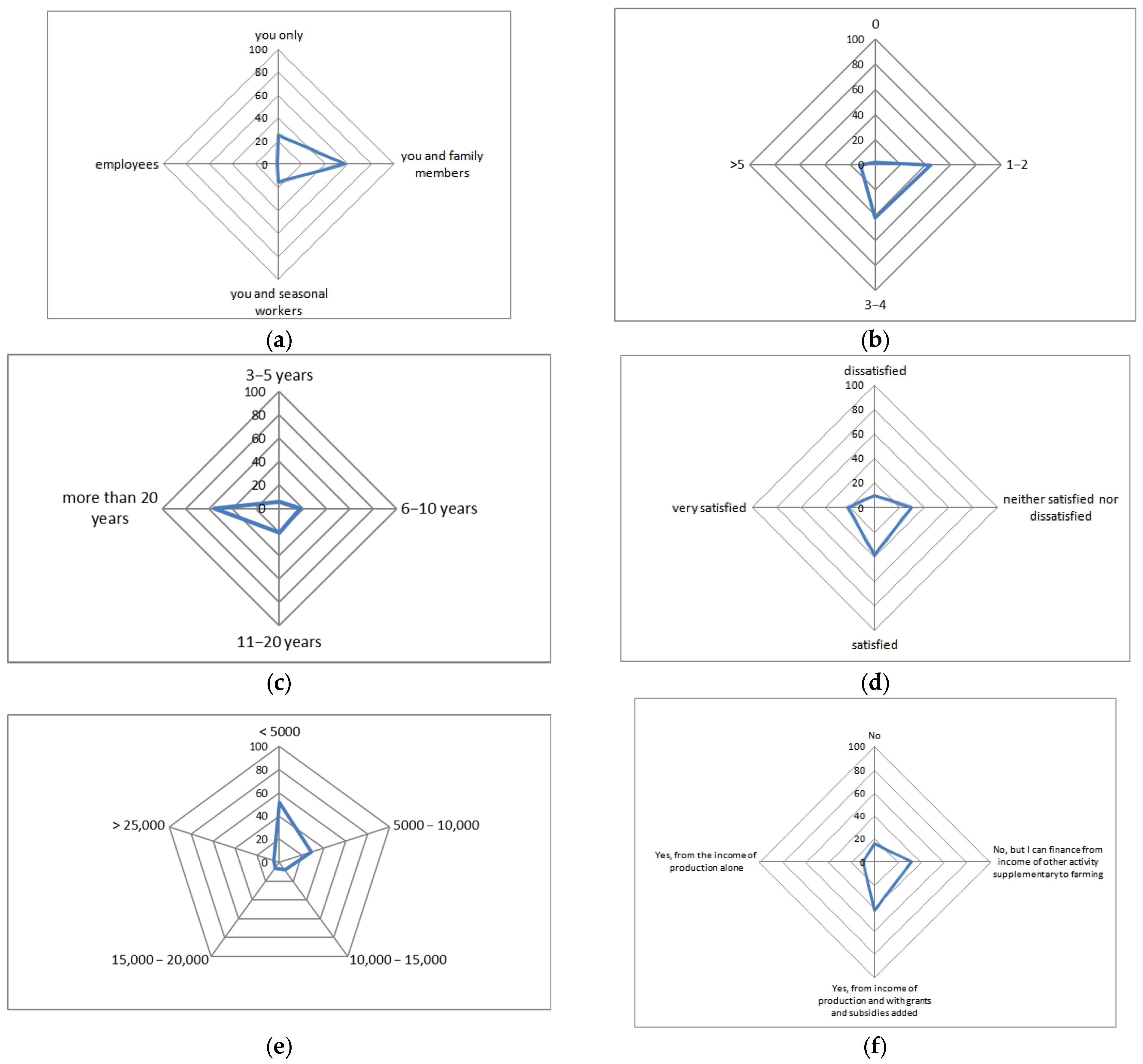

5.4. Economic Viability

- ▪

- Only 40% of the sample stated “farmer” as their main occupation, with the remaining 60% also being engaged with other job(s), e.g., civil servant, pensioner, freelancer.

- ▪

- Mainly the farmers themselves (26%) and their family (56%) work on their farm, while seasonal workers can be found only in the one fifth of the farms in the survey.

- ▪

- More than 40% of the interviewees said that they worked in their farms with 1–2 to 3–4 family members.

- ▪

- Around 60% began farming more than 10 years ago and another 20% started between 11 and 20 years ago.

- ▪

- As regards satisfaction from farming, the respondents usually say that they are “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their circumstances (60%), but it is rather important that 30% of the farmers are neither satisfied nor dissatisfied and another 10% are dissatisfied.

- ▪

- A significant number of farms are not viable (52% of the sample has an income from agriculture od less than EUR 5000 and 29% has one between EUR 5000 and 10,000) but perhaps provide their owners with additional income in pluri-active farm households, as many of the interviewees are engaged in more than one job.

- ▪

- Only 10% of the sample stated that their farm is profitable based on the income gained exclusively due to production. Most of the respondents (42%) indicated that they become profitable only if they take grants and subsidies into account, while 32% answered “no way” but they can finance their farming activity through other supplementary sources of income, and 16% claimed that their farm is clearly making a loss, which is confirmed from the answers related to income from farming.

6. Discussion

“One of the most distinctive problems in the diffusion of innovations is that the participants are usually quite heterophilous… usually on different variables knowledge and experience with an innovation, highly related to social status, education and the like”.

“It is not the same for an island region to sell a product like a sweet wine”.

“Important drivers of innovation are absent because of their “organizational thinness” and lack of dynamic clusters and support organizations and because of their distance to other regions and external knowledge”.

“They can see the world only through the eyes of the cooperative as they could not imagine themselves out of it”.

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Monge, M.; Hartwich, F.; Halgin, D. How Change Agents and Social Capital Influence the Adoption of Innovations Among Small Farmers: Evidence from Social Networks in Rural Bolivia; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kleysen, R.F.; Street, C.T. Toward a multi-dimensional measure of individual innovative behavior. J. Intellect. Cap. 2001, 2, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. The Diffusion of Innovation, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsouris, A. The role of Extension in Agricultural Technology Transfer: A critical review. In From Agriscience to Agribusiness—Theories, Policies and Practices in Technology Transfer and Commercialization; Kalaitzandonakes, N., Carayannis, E., Grigoroudis, E., Rozakis, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 337–359. [Google Scholar]

- Iwińska, K.; Bieliński, J.; Calheiros, C.S.C.; Koutsouris, A.; Kraszewska, M.; Mikusiński, G. The primary drivers of private-sphere pro-environmental behaviour in five European countries during the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 393, 136330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Lu, H.; Wang, X. Social capital, member participation, and cooperative performance: Evidence from China’s Zhejiang. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 49–78. [Google Scholar]

- Karampela, S.; Papazoglou, C.; Kizos, T.; Spilanis, I. Sustainable local development on Aegean Islands: A meta-analysis of the literature. Isl. Stud. J. 2017, 12, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, H.W.; Read, R. Insularity, remoteness, mountains and archipelagoes: A combination of challenges facing small states? In Proceedings of the Europe at the Margins: EU Regional Policy, Peripherality and Rurality Regional Studies Association Conference, Angers, France, 15–16 April 2004; University of Angers: Angers, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Proikaki, M.; Jones, N.; Vouros, P.; Evangelinos, K. Entrepreneurship and Social Capital in Island Regions. In Islandness and Sustainability: The Case of Aegean Islands; Spilanis, I., Kizos, T., Karampela, S., Eds.; University of the Aegean: Mytilene, Greece, 2015; pp. 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Galani-Moutafi, V. Rural space (re) produced–Practices, performances and visions: A case study from an Aegean island. J. Rural. Stud. 2013, 32, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/Eurostat. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, 3rd ed.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven, A.H. Central problems in the management of innovation. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.; Chepes, G.H.; Gheorghe, E.; Ene, H.; Larionescu, M. Socio-economic structures and diffusion of innovation in the Rumanian co-operative village. Sociol. Rural. 1971, 11, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, G. The contribution of ‘social capital’ to economic growth: Lessons from island jurisdictions. Round Table 2005, 94, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsouris, A.; Zarokosta, E. Farmers’ networks and the quest for reliable advice: Innovating in Greece. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2022, 28, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomay, K.; Tuboly, E. The role of social capital and trust in the success of local wine tourism and rural development. Sociol. Rural. 2022, 63, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint Ville, A. Using Social Network Analysis (SNA) to Map Social Capital and Social Networks of Smallholder Farmer Knowledge Networks to Enhance Innovation and Food Security Policy in the Caribbean Community; Research to Practice Policy Briefs; Institute for the Study of International Development, McGill University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Borzaga, C.; Sforzi, J. Social Capital, Cooperatives and Enterprises. In Social Capital and Economics: Social Values, Power and Social Identity; Christoforou, A., Davis, J.B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, G.; Hickey, G.M. Contrasting innovation networks in smallholder agricultural producer cooperatives: Insights from the Niayes Region of Senegal. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2016, 4, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena López, J.A.; Sánchez Santos, J.M. The Olson—Putnam Controversy: Some Empirical Evidence. Econ. Bull. 2007, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- King, B.; Fielke, S.; Bayne, K.; Klerkx, L.; Nettle, R. Navigating shades of social capital and trust to leverage opportunities for rural innovation. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 68, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigkas, M.; Partalidou, M.; Lazaridou, D. Trust and Other Historical Proxies of Social Capital: Do They Matter in Promoting Social Entrepreneurship in Greek Rural Areas? J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 12, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.-A.; Mills, J.; Ingram, J.; Dwyer, J.; Blackstock, K. Considering the source: Commercialisation and trust in agri-environmental information and advisory services in England. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 118, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.; Hung, A. Trust and financial advice. J. Pension Econ. Financ. 2021, 20, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Chervany, N.L. Conceptualizing trust: A typology and e-commerce customer relationships model. In Proceedings of the 34th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Caïs, J.; Torrente, D.; Bolancé, C. The Effects of Economic Crisis on Trust: Paradoxes for Social Capital Theory. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 153, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, A.H.; Lo, C. Robust emergency management: The role of institutional trust in organized volunteers. Public Adm. 2023, 101, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumarani, R.; Hangjunk, Z. Why people participate in online political crowdfunding: A civic voluntarism perspective. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 91, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzouramani, I.; Mantziaris, S.; Karanikolas, P. Assessing sustainability performance at the farm level: Examples from Greek agricultural systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljatović, A.; Tomaš Simin, M.; Vukoje, V. Key Determinants of the Economic Viability of Family Farms: Evidence from Serbia. Agriculture 2025, 15, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczyński, A.; Kołoszycz, E. Economic resilience of EU dairy farms: An evaluation of economic viability. Agriculture 2021, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Spreitzer, G.M. Explaining Change During Downsizing: The Effects of Trust, Empowerment, and Downsizing History on Survival. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 576–588. [Google Scholar]

- Nooteboom, B. Trust: Forms, Foundations, Functions, Failures and Figures; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Olson Jr, M. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, With a New Preface and Appendix; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971; Volume 124. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer, A.; McEvily, B.; Perrone, M. Does Trust Matter? Exploring the Effects of Interorganizational and Interpersonal Trust on Performance. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chloupkova, J.; Svendsen, G.L.H.; Svendsen, G.T. Building and destroying social capital: The case of cooperative movements in Denmark and Poland. Agric. Hum. Values 2003, 20, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.L. The future of U.S. agricultural cooperatives: A neoliberal perspective. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1995, 77, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uphoff, N. Understanding social capital: Learning from the analysis and experience of participation. Soc. Cap. A Multifaceted Perspect. 2000, 6, 215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, M. The Place of Social Capital in Understanding Social and Economic Outcomes. Can. J. Policy Res. 2001, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J. Social Capital and the Collective Management of Resources. Science 2003, 302, 1912–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampela, S.; Kizos, T.; Koutsouris, A. Discovering Innovation, Social Capital and Farm Viability in the Framework of the United Winemaking Agricultural Cooperative of Samos. Proceedings 2024, 94, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampela, S.; Kizos, T. Innovation and sustainability in rural households: Towards a theoretical framework. In Proceedings of the 16th ETAGRO Conference Sustainable Agriculture, Food Security, and Climate Change: Challenges and Opportunities in Bio-Economy, Athens, Greece, 9–10 October 2020; Agricultural University of Athens: Attica, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J.C. Counting the muses: Development of the Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOCS). Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.C.; Highhouse, S.; Nye, C.D. Development and validation of the general risk propensity scale (GRiPS). J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2019, 32, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenglass, E.; Schwarzer, R.; Jakubiec, D.; Fiksenbaum, L.; Taubert, S. The proactive coping inventory (PCI): A multidimensional research instrument. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference of the Stress and Anxiety Research Society (STAR), Cracow, Poland, 12–14 July 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oorschot, W.; Arts, W.; Gelissen, J. Social capital in Europe: Measurement and social and regional distribution of a multifaceted phenomenon. Acta Sociol. 2006, 49, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, H. Guidelines for Cooperative Legislation; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wine Plus. Vin & Gastronome. Available online: https://wineplus.gr/en/home/ (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- United Winemaking Agricultural Cooperative of Samos Greece. Available online: https://www.samoswine.gr/en/ (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Baran, M.; Hazenberg, R.; Iwińska, K.; Kasianiuk, K.; Perifanos, I.; Ferreira Da Silva, J.M.; Vasconcelos, C. Between innovative and habitual behavior. Evidence from a study on sustainability in Greece, Poland, Portugal, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 10, 1030418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalo, J.A.; Flynn, F.J.; Kim, S.H. Are two narcissists better than one? The link between narcissism, perceived creativity, and creative performance. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 1484–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ierapetritis, D.G. Social capital, regional development and innovation in Greece: An interregional analysis. Int. J. Innov. Reg. Dev. 2019, 9, 22–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N. Influence of emotional intelligence of employees on their innovative behaviour and the mediating effect of internal social capital. Rev. Argent. Clín. Psicol. 2020, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.F.; Sun, R. The influence of internal social capital on employees’ innovation behavior-based on the mediating effect of knowledge sharing. East China Econ. Manag. 2013, 27, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, B.; Buizer, M. Forests, discourses, institutions: A discursive-institutional analysis of global forest governance. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessein, J.; Bock, B.B.; De Krom, M.P. Investigating the limits of multifunctional agriculture as the dominant frame for Green Care in agriculture in Flanders and the Netherlands. J. Rural. Stud. 2013, 32, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räisänen, J.; Tuovinen, T. Digital innovations in rural micro-enterprises. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 73, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampela, S.; Perifanos, I.; Koutsouris, A. Digital skills: The gap between younger and experienced farmers in S-E Europe. In Proceedings of the 16th ETAGRO Conference Sustainable Agriculture, Food Security, and Climate Change: Challenges and Opportunities in Bio-economy, Athens, Greece, 9–10 October 2020; Agricultural University of Athens: Attica, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tödtling, F.; Trippl, M. One size fits all? Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1203–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsouris, A.; Zarokosta, E. Supporting bottom-up innovative initiatives throughout the spiral of innovations: Lessons from rural Greece. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 73, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROAKIS—Prospects for Farmers’ Support: Advisory Services in European AKIS. Agricultural Knowledge and Information Systems in Europe: Weak or Strong, Fragmented or Integrated? 2015. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/docs/results/311/311994/final1-20150928_pro-akis-final-publishable-summary-report.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Dakhli, M.; De Clercq, D. Human capital, social capital, and innovation: A multi-country study. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2004, 16, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baycan, T.; Öner, Ö. The dark side of social capital: A contextual perspective. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2022, 70, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, A. Social capital and economic development in regional Australia: A case study. J. Rural. Stud. 2006, 22, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluvankova, T.; Nijnik, M.; Spacek, M.; Sarkki, S.; Perlik, M.; Lukesch, R.; Melnykovych, M.M.; Valero, D.; Brnkalakova, S. Social innovation for sustainability transformation and its diverging development paths in marginalised rural areas. Sociol. Rural. 2021, 61, 344–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, E.; Koutsouris, A. The agronomist to trust as my advisor: A Greek case study. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2025, 31, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frater, P.; Franks, J. Measuring agricultural sustainability at the farm-level: A pragmatic approach. Int. J. Agric. Manag. 2013, 2, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, D.; Ranjbar, Z.; Karami, E. Measuring agricultural sustainability. In Biodiversity, Biofuels, Agroforestry and Conservation Agriculture; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Latruffe, L.; Diazabakana, A.; Bockstaller, C.; Desjeux, Y.; Finn, J.; Kelly, E.; Ryan, M.; Uthes, S. Measurement of sustainability in agriculture: A review of indicators. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2016, 118, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sălășan, C.; Moisa, S.; Bălan, I.M.; Dumitrescu, C. General innovation framework and the innovation expectations of rural actors. Rev. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2017, 6, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Innovation for Sustainable Rural Development; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Aspects | Dimensions | Variables | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Proposed types of innovation | Product innovation | 1 |

| Process innovation | 2 | ||

| Marketing innovation | 3 | ||

| Organizational innovation | 4 | ||

| Pro-Innovative Behavior (PIB) | Kaufman’s (2012) Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOC) (Self-Everyday Creativity Subscale Only) [48] | Finding something fun to do when I have no money | 1 = Much Less Creative 2 = Less Creative 3 = Neither More Nor Less Creative 4 = More Creative 5 = Much More Creative |

| Helping other people cope with a difficult situation | |||

| Teaching someone how to do something | |||

| Maintaining a good balance between my work and my personal life | |||

| Understanding how to make myself happy | |||

| Being able to work through my personal problems in a healthy way | |||

| Thinking of new ways to help people | |||

| Choosing the best solution to a problem | |||

| Planning a trip or event with friends that meets everyone’s needs | |||

| Mediating a dispute or argument between two friends | |||

| Getting people to feel relaxed and at ease | |||

| General Risk-Taking Propensity (GRiPS) [49] | Taking risks makes life more fun | 1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neither Agree Nor Disagree 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree | |

| My friends would say that I’m a risk taker | |||

| I enjoy taking risks in most aspects of my life | |||

| I would take a risk even if it meant I might get hurt | |||

| Taking risks is an important part of my life | |||

| I commonly make risky decisions | |||

| I am a believer of taking chances | |||

| I am attracted, rather than scared, by risk | |||

| Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI) [50] | I am a take charge person | 1 = Not At All True 2 = Hardly True 3 = Moderately True 4 = Exactly True | |

| I try to let things work out on their own | |||

| After attaining a goal, I try to look for another more challenging one | |||

| I like challenges and beating the odds | |||

| I visualize my dreams and try to achieve them | |||

| Despite numerous setbacks, I normally succeed in getting what I want | |||

| I often see myself failing so I try not to get my hopes up too high | |||

| When I apply for a position, I imagine myself filling it | |||

| I turn obstacles into positive experiences | |||

| If someone tells me I can’t do something, you will be sure that I will do it | |||

| When I experience a problem, I take the initiative in solving it | |||

| When I have a problem, I usually see myself in a no-win situation | |||

| Trust (T) | Social trust (ST) | Most people can be trusted or you can’t be too careful (generalized trust) | 0–10 (low to high level) |

| Most people can be trusted or you can’t be too careful (particularized trust: neighbors, family, friends) | |||

| Most people are fair or try to take advantage of you (fairness-equity) | |||

| Institutional trust (IT) | National Government | 0–10 (low to high level) | |

| Ministry of Rural Development and Food | |||

| United Winemaking Agricultural Cooperative of Samos | |||

| Directorate of Rural Economy and Veterinary of Samos | |||

| Municipality-Local authority | |||

| European Union | |||

| Formal Social networks (FSN) | Members of NGOs | 0 = No 1 = Yes | |

| Voluntary work for NGOs | |||

| Economic Viability (EV) | Main occupation | Farmer or something else (MO) | 0 = No |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| Employment | Workers on the farm (WF) | 1 = you only 2 = you and family members 3 = you and seasonal workers 4 = employees | |

| Number of family members (FMs) | 0 = 0 1 = 1–2 2 = 3–4 3 = >5 | ||

| Years in farming | (YF) | 1 = Less than 3 years 2 = 3–5 years 3 = 6–10 years 4 = 11–20 years 5 = more than 20 years | |

| Satisfaction from farming | (SF) | 1 = very dissatisfied 2 = dissatisfied 3 = neither satisfied nor dissatisfied 4 = satisfied 5 = very satisfied | |

| Earnings from the activities | Income from farming (I) | 1 = <5000 2 = 5000–10,000 3 = 10,000–15,000 4 = 15,000–20,000 5 = 20,000–25,000 6 = >25,000 | |

| Farm profitability | (FP) | 0 = No 1 = No, but I can finance from income of other activity supplementary to farming 2 = Yes, from income of production and with grants and subsidies added 3 = Yes, from the income of production alone |

| Types of Innovation | For the Farm N (%) | For the Cooperative N (%) | Examples Referred |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Product innovation | 8 (25%) | 12 (32%) | ● new products ● new services (agritourism) |

| 2. Process innovation | 15 (47%) | 7 (18%) | ● new equipment ● development of new applications related to information technology |

| 3. Marketing innovation | 3 (9%) | 9 (24%) | ● e-shop ● direct selling ● development of distribution network(s) |

| 4. Organization innovation | 6 (19%) | 10 (26%) | ● training for the members ● sharing knowledge from various members and agronomists of the cooperative ● broaden external relations |

| Total | 32 (100%) | 38 (100%) |

| Variables | Values | N Total | % | Pro-Innovative Behavior (PIB) | Trust (T) | Economic Viability (EV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (N = 86) | Male | 66 | 66 | 3.06 | 1.42 | 2.30 |

| Female | 20 | 20 | 3.26 | 1.57 | 2.37 | |

| Total | 86 | 86 | 3.11 | 1.46 | 2.32 | |

| Age (N = 86) | 18–30 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 31–45 | 28 | 28 | 3.20 | 1.52 | 2.22 | |

| 46–60 | 44 | 44 | 3.00 | 1.41 | 2.32 | |

| More than 60 | 14 | 14 | 3.25 | 1.49 | 2.52 | |

| Total | 86 | 86 | 3.11 | 1.46 | 2.32 | |

| Education (N = 86) | Primary education | 9 | 13 | 3.11 | 1.09 | 2.43 |

| Secondary education | 21 | 24.4 | 3.09 | 1.47 | 2.28 | |

| Post-secondary non-tertiary education | 34 | 39.5 | 3.06 | 1.63 | 2.38 | |

| Short-cycle tertiary education | 13 | 15.1 | 3.18 | 1.54 | 2.00 | |

| Bachelor’s or equivalent level | 15 | 17.4 | 3.22 | 1.33 | 2.39 | |

| Master’s or equivalent level | 3 | 3.5 | 3.51 | 1.93 | 1.75 | |

| Total | 86 | 100.0 | 3.13 | 1.47 | 2.30 | |

| Main occupation (N = 86) | Farmer | 34 | 39.5 | 3.11 | 1.32 | 2.53 * |

| Other | 52 | 60.5 | 3.17 | 1.45 | 2.15 * | |

| Total | 86 | 100.0 | 3.13 | 1.40 | 2.30 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karampela, S.; Kizos, T.; Koutsouris, A. The Interplay of Pro-Innovative Behavior, Trust, and Farm Viability for Sustainability in the United Winemaking Agricultural Cooperative of Samos. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181921

Karampela S, Kizos T, Koutsouris A. The Interplay of Pro-Innovative Behavior, Trust, and Farm Viability for Sustainability in the United Winemaking Agricultural Cooperative of Samos. Agriculture. 2025; 15(18):1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181921

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarampela, Sofia, Thanasis Kizos, and Alex Koutsouris. 2025. "The Interplay of Pro-Innovative Behavior, Trust, and Farm Viability for Sustainability in the United Winemaking Agricultural Cooperative of Samos" Agriculture 15, no. 18: 1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181921

APA StyleKarampela, S., Kizos, T., & Koutsouris, A. (2025). The Interplay of Pro-Innovative Behavior, Trust, and Farm Viability for Sustainability in the United Winemaking Agricultural Cooperative of Samos. Agriculture, 15(18), 1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181921