Abstract

Centella asiatica (L.) Urban or Asiatic pennywort is an important medicinal plant used in traditional medicine, cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries; it is also an indigenous vegetable in Asian countries. A total of 169 Centella accessions were collected from all regions of Thailand and assessed for 29 traits, including morphological traits, plant biomass, and centelloside contents. Experiments were conducted in two growing systems, soil and hydroponics, with two harvests every month. The centelloside concentrations were determined by high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) procedure. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), correlation matrix, genetic parameters, principal component analysis (PCA), and hierarchical clustering were determined both across all environments and for each growing system separately. The ANOVA revealed significant differences in genotypes and growing systems, along with their interactions. Hydroponic culture produced three- to four-fold higher biomass than soil system while triterpenoid sapogenin concentrations were notably greater in hydroponics. Biomass-related traits showed strong positive correlations with centelloside yields, and genetic analyses revealed moderate to high heritability for these characteristics. PCA and cluster analyses classified accessions into four distinct groups, identifying elite genotypes with both high biomass and centelloside yield. These findings provide a solid foundation for targeted selection in Centella breeding programs.

1. Introduction

Centella asiatica (L.) Urb., commonly known as Indian pennywort, Asiatic pennywort, or gotu kola, is a perennial herbaceous plant belonging to the Apiaceae family. It is a creeping plant with slender, stoloniferous stems that can root at the nodes. It typically grows up to 50 cm long, spreading horizontally across the ground. The leaves are simple and round to reniform (kidney-shaped), and are borne on long petioles. This plant prefers damp, swampy environments and is commonly found in wetlands, along riverbanks, and in other moist habitats [1]. It has a widespread distribution across the globe, primarily in tropical and subtropical regions including Africa, Asia, Australia, and islands in the western Pacific Ocean [2]. In Asian countries, this plant is distributed in tropical regions, especially in the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and some parts of East Asia, with reports of it being found in India, Sri Lanka, China, Japan, Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand [3,4,5]. People from these areas have used it for centuries in traditional medicine systems including Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, and Unani medicine [6]. As well as being used for skin treatment, C. asiatica is also recommended for memory and cognitive enhancement, as a treatment for nervous system disorders, for improving mental health, and for reducing symptoms in the digestive system [7]. In addition, this medicinal herb is also known for cardioprotective, neuroprotective, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities [8].

Key active compounds in C. asiatica, known as centellosides, include asiaticoside, asiatic acid, madecassoside, and madecassic acid. Asiatic acid and madecassic acid are triterpenoid sapogenins, while asiaticoside and madecassoside are their corresponding triterpenoid saponins formed via glycosylation [9]. Other phytochemicals include phenolic acids, triterpene steroids, volatile oils, flavonoids, tannins, and phytosterols [10]. Centellosides exhibit diverse pharmacological activities, such as neuroprotection, anti-aging, anti-inflammation, antioxidant effects, and wound healing, with applications in cognitive health, dermatology, and tissue regeneration [11,12].

Centella asiatica can be grown in well-drained, rich, and moist soils with a pH of 6–7 and is able to tolerate waterlogged soil. Seeds or runners are used for planting and plants can be harvested 30–60 days after planting from runners or up to 100 days from seed germination depending on accessions or the environment [13]. Although soil cultivation is common for pennywort production, several studies have reported that soil contamination posed a significant challenge in the production of C. asiatica, particularly due to the accumulation of heavy metals [14,15]. In addition, soil-borne pathogens such as Sclerotium spp. and Ralstonia solanacearum reduce the biomass yield significantly [16]. Besides conventional production, hydroponic systems have been used to produce numerous medicinal plants, including C. asiatica. Centelloside accumulation and biomass have been significantly increased in hydroponic growing systems by adjusting the electrical conductivity (EC) and pH of the nutrient solution. Moreover, a hydroponic system provides a clean cultivating environment, reducing soil-borne diseases and contamination which is crucial for medicinal plant production [17].

There have been several reports from different countries on differences in the amount of plant biomass and centelloside contents in plants from different locations, which can be the result of several environmental factors, such as soil type, temperature, humidity, shading, altitude, and cultivation practices [13,18]. However, genetic diversity is the key factor in the variation in centelloside contents. Wild accessions from different areas in India and Nepal contained various concentrations of centellosides, ranging from 0.34 to 8.13 of asiaticoside [3,19,20,21,22]. In Malaysia, accessions from different regions were tested to detect the different chemical profiles between three triterpenes and four triterpene compounds which highlighted the importance of germplasm collection from several locations [23,24]. Additionally, Truong et al. [25] have investigated 26 accessions of C. asiatica from Vietnam and Laos and found the diverse morphologies and genetic diversity from the collection. Two accessions have been selected as elite cultivars for local production.

Recently, some studies on C. asiatica cultivation and determination of centelloside contents have been conducted in Thailand [26,27,28,29,30,31]. For instance, two studies assessed the effects of water irrigation on a C. asiatica accession from Nakhon Pathom Province by measuring photosynthetic parameters, biomass, and centelloside content [26,27]. Another study employed a hydroponic system with different nutrient formulas and light intensities to improve the yield and phytochemical content of C. asiatica collected from Chumphon Province [28]. Additionally, 25 accessions of C. asiatica from 22 provinces across Thailand were collected and evaluated for genetic diversity across three seasons, revealing that centelloside concentrations varied according to location and harvesting season [31]. However, the accessions examined in these studies do not represent the full range of cultivation areas in Thailand. Despite the plant’s widespread use, there is lack of information on how genotype, environment, and their interaction affect the performance of different Centella germplasm. Furthermore, comparative studies between traditional soil cultivation and hydroponic systems, particularly for evaluating potential improvements in biomass and phytochemical production, remain limited.

To address these gaps, this study provides a comprehensive evaluation of key traits in C. asiatica. We compared the performance of 169 accessions from Thailand and other countries grown under both hydroponic and conventional soil systems. Specifically, we assessed agro-morphological variation within Thai germplasm, analyzed genotype-by-environment interactions (GEI) and heritability, and identified high-performing accessions as candidate parents for breeding. Elite accessions selected for yield improvement can benefit traditional cultivation for local farmers, while those with high centelloside content can support commercial production for the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Sites

A total of 169 Asiatic pennywort (Centella asiatica (L.) Urb.) accessions were collected from six different areas in Thailand and other countries (Table S1). All plants were grown in the greenhouse at the National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA) and selected to develop pure lines. All 169 pure lines were propagated in vitro for four weeks; hardened for two weeks under conditions of 28 ± 2 °C, PPFD 50–100 μmol m−2 s−1, and 16 h. per day; and used as plant materials.

2.2. Experimental Design

The experiment was conducted in a randomized complete block design (RCBD), with five replications per system with one plant per replication. For the soil system, plants from tissue culture were transferred to peat moss and grown under greenhouse conditions. The soil experiment was conducted at the Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Kasetsart University, Bangkok. For the hydroponic system, plants were transferred to a dynamic root floating technique (DRFT) hydroponic system in Enshi solution at a pH 5.5–6.0 and EC of 1.8–2.0 mS cm−1 [32]. The hydroponic experiment was conducted in a netted greenhouse at the Rice Science Center, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Nakhon Pathom. Plants in both systems received full sunlight conditions at a light intensity of 350–450 μmol m−2 s−1, 32 ± 1 °C and relative humidity of 50 ± 10%. The above-ground tissue of each plant was collected every month after planting and used to evaluate phenotypic traits.

2.3. Trait Evaluation

A total of 29 traits were assessed. For each plant, we recorded the number of leaves from the main plant (ML), leaves from the stolon (SL), petiole thickness (PT), longest petiole from the main plant (PH) to represent plant height, color of stolon (SC), number of stolons (S), length of the longest stolon (SMax), and average length of stolons (SAv). Subsequently, samples were separated into three parts—the leaf, petiole, and stolon—and their fresh and dried biomasses were measured. Dried leaves were used to extract the chemical profile of centelloside contents, including asiaticoside, asiatic acid, madecassoside, and madecassic acid, and measured by high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) using a method modified from Singh et al. (2022) [21]. Crude extract analysis was carried out on 20 × 10 cm TLC aluminum precoated plates (normal phase) with a 0.2 mm layer of silica gel 60 F254 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Spots (extracts and standards) with a bandwidth of 6 mm were applied on HPTLC plates and positioned 10 mm from the bottom and 15 mm from the side with a Linomat 5 automated TLC applicator (CAMAG, Muttenz, Switzerland) using a CAMAG 100 μL syringe under a 150 nL/s flow rate of N2 gas. The plate was developed in a twin tank chamber 20 × 10 cm with a solvent system for 25 min. The solvent system consisted of chloroform/ethylacetate acid/methanol/water (6:20:8.8:4, v/v/v/v). The plates were allowed to develop up to 8 cm from the application point for complete separation of bands. For the visualization of bands, the plates were derivatized with 10% sulfuric acid reagent, followed by densitometric scanning at 513 nm using a CAMAG TLC scanner 3 (CAMAG, Muttenz, Switzerland). Quantification of selected active markers in the sample(s) was performed using a Camag VisionCATS 4.1 (CAMAG, Muttenz, Switzerland) software based on the regression curve of standard markers and is expressed as a percentage (%) of the dry weight of the crude sample. The yield of each phytochemical per plant was calculated by multiplying the chemical concentration by the dried biomass of each plant. The trait evaluation is presented in Table S2.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software v.4.2.0 [33]. Significant differences in genotypes and the interaction between the genotype and cut and genotype and system were determined using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedure at the level of Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT), with p ≤ 0.05, in the Agricolae R package v.1.3-7 [34]. The correlations among traits were determined using the Pearson correlation coefficient formula and visualization using the Corrplot R package v.0.92 [35]. The phenotypic, genotypic, and environmental variations, along with the broad sense heritability (H2) and genetic advance (GA) with 5% selection intensity were calculated with variability R package v.0.1.0 [36]. The Factoextra R package v.1.0.7 was utilized for the principal component analysis (PCA) with the z-score standardization [37]. The dendextend package (v.1.19.1) in R was used to generate dendrograms of phenotypic variation through hierarchical clustering [38].

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Identification and Variation

Based on the 169 accessions, Table S2 summarizes 29 traits, showing the range, mean, SD, SE, and CV across all environments, plus the means and SE for each growing system. In terms of morphological characteristics, plants in the hydroponic system had bigger canopies with 9.08 cm in PH and 28.52 cm in SMax, compared with 7.30 cm and 20.76 cm, respectively, in soil production. Moreover, plants grown in the hydroponic system produced more leaves from both main (25.69) and stolon (29.18) plants, while we could harvest only 10.10 (ML) and 10.08 (SL) from the soil system. The overall FW across all environments ranged from 0.01 to 140.89 g, while the DW ranged from 0.0001 to 15.149 g per plant with average of 11.59 and 1.40 g, respectively. The FW in hydroponic (17.60 g) was three times higher than the FW in soil (5.41 g), similar to the DW results (2.24 g in hydroponic and 0.57 g in soil). Each phytochemical compound had a wide range from 0 to over 100 mg/g DW in A and AA, while the maximum concentrations of M and MA reached over 439 and 229 mg/g DW, respectively. The average concentrations of A and M were similar in the overall results, and those for the soil and hydroponic systems, reaching 11.84, 11.23 and 11.95 mg/g DW in A and 17.99, 17.10, and 18.24 mg/g DW in M, respectively. On the other hand, concentrations of triterpene sapogenins (AA and MA) were much higher in the hydroponic system, at 7.00 and 13.06 mg/g DW, respectively. All centellosides were due to a larger plant biomass. Most morphological traits had a lower coefficient of variation, ranging from 29 (LW) to 99% (SL), whereas the biomass yield (FW and DW) and phytochemical traits (both concentrations and yields) had higher value, from 113 (LFW) to 218% (YA).

Table 1 represents the results from the analysis of variance (ANOVA), including significant differences in genotypes, cuts, and systems, as well as the interaction between genotypes and cuts and genotypes and systems. All traits had highly significant differences in genotype (p ≤ 0.001). Most traits also had statistical differences in cuts and systems, except LP in cuts and A and M in the system. The interactions between genotypes and systems exhibited strongly significant differences in most traits, except the concentration of asiaticoside; however, half of the traits did not present statistically significant interactions between genotypes and cuts, especially in morphological traits such as the number of leaves, plant height (PH) and leaf size (LA).

Table 1.

ANOVA results with genotypes, cuts, growing systems, and interactions between genotype and cut, and genotype and system.

3.2. Analysis of Correlation Matrix

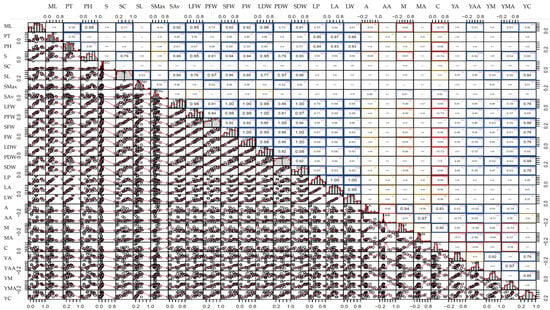

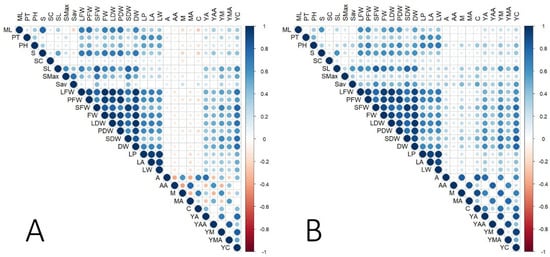

Correlation matrix is a valuable tool to identify trait associations that can be exploited in selection strategies and to elucidate the biological relationships within the germplasm. This correlation matrix of all phenotypic traits across all environments is presented in Figure 1 and Table S3. The FW had a significant positive association with several morphological traits, including the number of leaves (ML, r = 0.76; SL, r = 0.75), stolon traits (S, r = 0.78; SMax, r = 0.44), and leaf size (LP, r = 0.62; LA, r = 0.61; LW, r = 0.59), which was similar to the results for DW. The concentrations of phytochemicals did not have any associations with plant morphological traits but were positively correlated with the yields of those compounds. However, the concentrations of triterpene saponins (A and M) were slightly negatively correlated with the concentrations of triterpene sapogenins (AA and MA) with −0.14 ≤ r ≤ −0.24. The phytochemical yields (YA, YAA, YM, YMA, and YC) revealed stronger positive correlations with biomass-related traits such as DW with r = 0.51, 0.59, 0.61, 0.60, and 0.80, respectively, than with the concentrations of those compounds. Comparing the association between the phenotypic data from each growing system (Figure 2A,B and Tables S4 and S5), the concentrations of phytochemicals tended to have negative correlations with the biomass traits in the hydroponic system while positive correlations were observed in the soil system. This was similar to the results from the correlations between the concentrations of terpenoid saponins (A and M) and triterpene acids (AA and MA), which were highly negatively correlated in the hydroponic system and did not exhibit any associations in the soil system.

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits of Centella asiatica accessions across all environments (growing system and cut). The lower left panels show scatter plots with fitted regression lines between each pair of traits. The diagonal panels display the histogram distribution of each trait. The upper right panels in the boxes represent Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r), with significance indicated by asterisks (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001). Blue boxes represent statistically positive correlations whereas red, orange and yellow boxes represent statistically negative correlations. The color intensity reflects the strength of the correlations. Trait abbreviations correspond to morphological, biomass and centelloside-related measurements described in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Correlation matrices of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits of Centella asiatica grown under two cultivation systems: hydroponic system (A) and soil-based system (B). Each cell represents the correlation between a pair of traits, with circle size proportional to the correlation coefficient magnitude and color indicating direction: blue for positive correlations and red for negative correlations. Darker shades represent stronger correlations, as shown by the scale bar (r = −1 to +1). Trait abbreviations corresponding to morphological, biomass, and centelloside-related measurements listed in Table 1.

3.3. Analysis of Genetic Components

Phenotypic, genotypic, and environmental variances; the coefficients of phenotype, genotype, and environment, as well as broad-sense heritability; genetic advance; and the percentage of the mean of genetic advance are all presented in Table 2, which reveals the wide range of phenotypic and genotypic variations. All phenotypic variances are higher than genotypic variances. The phenotypic and environmental coefficients of variance produced similar results to the highest yield of asiaticoside and the smallest leaf width, accounting for 197.96 and 174.37 in YA and 29.76 and 18.17 in LW, respectively. However, the genotypic coefficient of variance ranged from 16.15 (MA) to 96.40 (PFW). The values of broad-sense heritability were estimated and we found that some traits had low heritability values, especially in the concentration of each centelloside compound, which ranged from 0.06 in M to 0.10 in AA; the yield of phytochemicals had higher heritability values, which were responsible for 0.22 in YA, 0.13 in YAA, 0.30 in YM, 0.17 in YMA, and 0.37 in YC. In this study, we found that the heritability of biomass-related traits had significantly higher values, which ranged from 0.14 (S), 0.25 (ML), and 0.26 (SL) to over 0.60 in leaf traits (0.63 (LW), 0.63 (LP), and 0.64 (LW)). In addition, genetic advance, which represents the improvement of a trait to the next generation, was high in the biomass and yields of phytochemicals, accounting for 97% (DW) and 104.7% (YC), respectively.

Table 2.

Genetic components of 29 traits of Centella asiatica across growing systems.

3.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

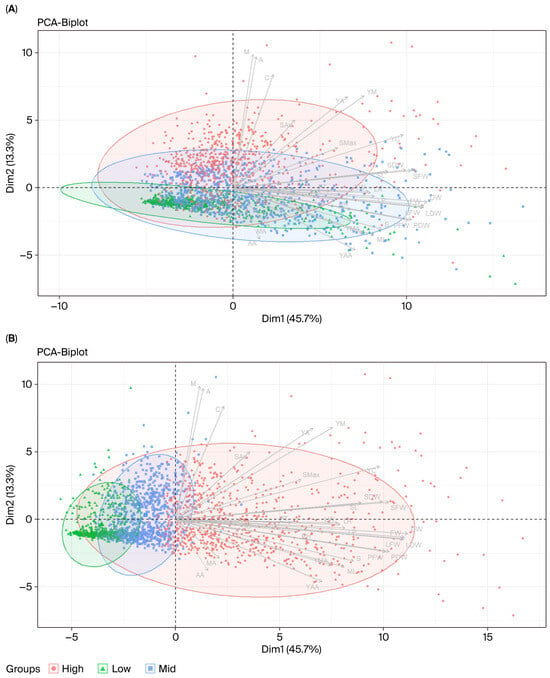

To illustrate the genetic variability among Centella genotypes, a principal component analysis of standardized data was applied to show the relationship among traits. The results of this analysis of the principal components across all environments, which are presented in Table S6 showed that principal component (PC) 1 was responsible for 45.74% of the total variation, and that the traits that were responsible for genotype separation along this axis were biomass-related traits (LFW, PFW, SFW, FW, LDW, PDW, SDW, and DW), of which DW and FW accounted for the highest coefficients of variation at 0.267 and 0.263, respectively. The second principal component (PC2) accounted for 13.27% of the total variation; and was associated with the characteristics of phytochemical concentrations (A = 0.432; M = 0.439; and C = 0.373) and yields (YA = 0.300 and YM = 0.303). Approximately 10.28% and 7.13% of the variation belonged to PC3 and PC4, respectively. These two PCs were represented by leaf size traits (LP = 0.248 and 0.331; LA = 0.249 and 0.338; and LW = 0.245 and 0.350). The genotype vs. trait biplot analysis using PC1 and PC2 explained approximately 58.7% of the total trait variation and separated the accessions of C. asiatica into three groups with low, medium, and high centelloside concentrations and plant biomass yields (Figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

PCA biplots of Centella asiatica accessions grouped by centelloside concentration (A) and biomass (B) with the combined data from both hydroponic and soil-based systems. Each point represents an accession, with colors indicating group classification: high (orange), medium (blue), and low (green). Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals for each group. Arrows indicate trait loadings, showing the direction and strength of each trait’s contribution to the principal components. Dim 1 and Dim 2 represent the first and second principal components, explaining 45.7% and 13.3% of the total variation, respectively. Trait abbreviations corresponding to morphological, biomass, and centelloside-related measurements listed in Table 1.

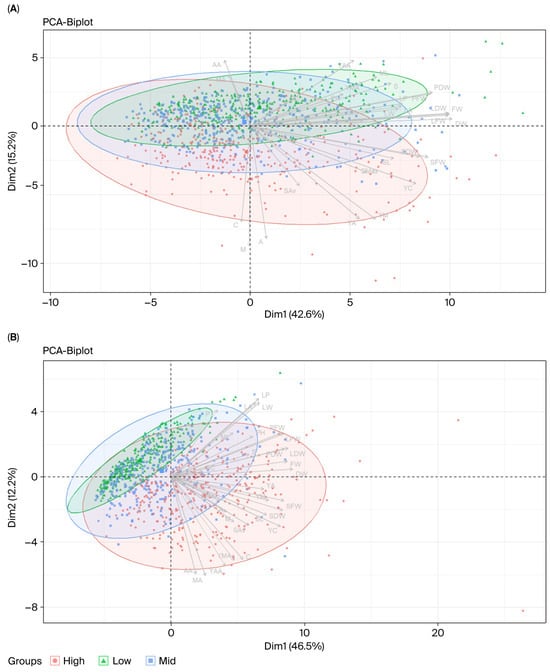

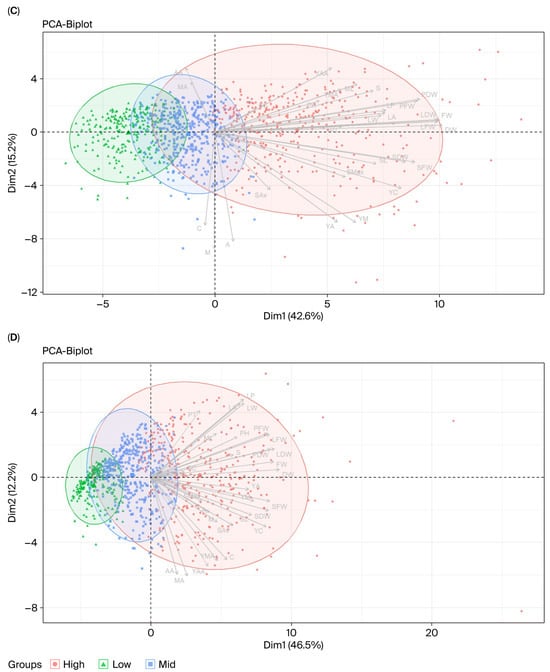

To differentiate the results for the growing system, PCAs were conducted based on the data for each system separately, as shown in Tables S7 and S8. In the hydroponic system, PC1, PC2 and PC3 accounted for 42.60, 15.18 and 11.19% of the total trait variation, respectively; meanwhile, the percentages of variance were 46.50, 12.22, and 11.65 in PC1, PC2, and PC3 in the soil system. The PC1 values of both systems were correlated to biomass-related traits (LFW, PFW, SFW, FW, LDW, PDW, SDW, and DW), similarly to the principal component based on the overall data. However, PC2 of the hydroponic system was explained by asiatic acid and madecassic acid concentrations and yields, while PC2 of the soil system was described by leaf size traits. The genotypes of asiatic pennywort grown in the soil system could be more easily discriminated based on the concentration of centelloside than the hydroponic or across environments (Figure 3A and Figure 4A,B). Accessions in the hydroponic system could simply be categorized into low, medium, and high yields, which was different to the PCAs of the soil-grown plants or across environments (Figure 3B and Figure 4C,D).

Figure 4.

PCA biplots of Centella asiatica accessions grouped by centelloside concentration (A,B) and biomass (C,D) in hydroponic and soil cultivation systems. Each point represents one accession, classified into high (orange), medium (blue), or low (green) groups. Panels (A,B) show PCA results for centelloside concentrations from hydroponic and soil systems, respectively, while panels (C,D) show PCA results for biomass in the same systems. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals for each group. Arrows indicate trait loadings, with their direction and length reflecting the contribution of each morphological, biomass, or phytochemical trait to the principal components. Dim1 and Dim2 correspond to the first and second principal components, explaining 42.6–46.5% and 12.2–15.2% of the total variation, respectively. Trait abbreviations are listed in Table 1.

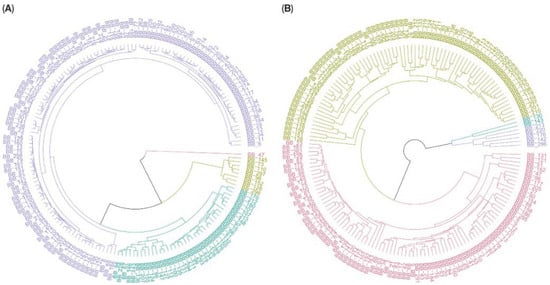

3.5. Euclidean Distance and UPGMA Dendrogram

The homogenized data was used to calculate the Euclidean distances across the 169 accessions, and a UPGMA dendrogram was created based on the combined data from both environments, as well as the data from the hydroponic and soil systems separately, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. Based on the overall data, C. asiatica lines were categorized into four groups based on 29 traits. Group 1 (purple) included BB_296, BB_128, BB_98, BB_297, BB_152, BB_73, and BB_173 and represented lines with high performance. Similarly, UPGMA dendrograms from hydroponic and soil systems were used to separate plant accessions into four groups. Nevertheless, the members of each group from each dendrogram were different. In the hydroponic system (Figure 6A), BB_47 was dissociated from the rest and became Group 1 (red), while Group 2 (green) comprised eight accessions: BB_296, BB_128, BB_152, BB_98, BB_297, BB_110, BB_73 and BB_145. In the soil system (Figure 6B), Group 1 (turquoise) had two lines, BB_130 and BB_143 while Group 2 (purple) included BB_213, BB_220, BB_176, BB_142, and BB_296.

Figure 5.

Circular hierarchical clustering dendrogram of 169 Centella asiatica accessions, based on 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits with the combined data from both hydroponic and soil-based systems. Accessions are grouped into four distinct clusters, represented by different colors, reflecting similarities in their overall phenotypic profiles. The purple and green clusters represent the high-performing accessions compared with other groups.

Figure 6.

Circular hierarchical clustering dendrograms of 169 Centella asiatica accessions grown under (A) hydroponic and (B) soil systems, based on 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits. Each dendrogram groups the 169 accessions into four color-coded clusters according to similarities in their standardized trait profiles. The red and light green clusters in (A) represent the high-performing accessions from hydroponic system, whereas the purple and green clusters in (B) represent the high-performing accessions from the soil-based system.

3.6. Selection of Highest-Performing Accessions

Selecting the highest-performing accessions across growing systems/cuts was also one of the purposes of this study. Among the 169 accessions of C. asiatica, 10 elite lines were selected, as shown in Table 3. These lines had a higher number of leaves with many long stolons and large leaves which influenced the biomass yields. All lines accumulated moderate to high concentrations of centellosides, resulting in the largest amount of centelloside yields. We also selected the elite lines for each system (Tables S10 and S11). Regarding the growing systems, BB_98 and BB_296 were the two highest-performing accessions in both growing systems.

Table 3.

Phenotypic data used for plant selection of 10 elite accessions of Centella asiatica, selected based on the combined data from both hydroponic and soil-based systems.

4. Discussion

In this study, we explored 29 morphological and phytochemical traits of C. asiatica grown in both soil and hydroponic systems with two cuttings. To obtain the 169 accessions (Table S1), the largest germplasms of Asiatic pennywort across Thailand and neighboring countries were used, covering 35 provinces and 165 locations in Thailand, which is 13 provinces more than what was covered in the previous studies [22,39,40,41]. Morphological traits, such as plant height, number of plant organs, and leaf size, showed lower coefficients of variation (CV) than biomass and centelloside-related traits (Table S2), as was confirmed by Singh et al. [42]. Although no previous studies have compared soil and hydroponic systems, reviewing multiple articles, we found that growing C. asiatica in hydroponic systems resulted in a higher plant biomass [17,28,43,44], which aligns with our results that the FW and DW of plants grown in the hydroponic system were three and four times, higher than from soil cultivation. in terms of centelloside concentrations, our study revealed similar concentrations of triterpenoid saponins in plants from both systems but over three times higher triterpenoid sapogenin concentrations in plants from the hydroponic system. However, inconsistency of centelloside concentrations, such as asiaticoside, was reported in both soil (from 0.4 to 19.8 mg/g DW; Kunjumon et al. [40], 1.7–16.3 mg/g DW; Mathur et al. [45] and 5–40.4 mg/g DW; Rohini and Smitha [46]) and hydroponic systems (18 mg/g DW; Shawon et al. [17] and 3.37 mg/g DW; Harakotor et al. [28]).

All traits affirmed significant genotypic effects (p ≤ 0.001, Table 1), suggesting the presence of valuable genetic variation for Centella breeding program. The environments (cut and system) were also statistically significant in most traits (except LP in cut and A and M in system), suggesting that plants should be selected for each growing system to obtain the maximum biomass and centelloside yields. Both genotypic and G × E interactions were found, in accordance with previous research [47].

A correlation matrix is a powerful method for determining selection strategies through indirect selection when there are strong correlations between easily selected traits and traits that are more difficult or expensive to measure [48]. The number of leaves (ML and SL) were positively correlated with the plant biomass and leaf size traits (Figure 1), which is consistent with the study by Chachai et al. [39]. Highly positive correlations for biomass and yields of centellosides indicated that the total yields of centelloside in this study depended on the biomass production rather than the accumulation of each phytochemical. In the hydroponic environment, there were negative correlations between C and ML (Figure 3A), along with negative correlations with leaf size traits, as was also confirmed by Rohini and Smitha’s results [46]. Triterpenoid saponin (A and M) exhibited significantly negative correlations with triterpenoid sapogenin concentrations (AA and MA), which can be explained by the centelloside biosynthetic pathway [49].

Genetic component analysis provides crucial information for estimating the degree of heritability and for evaluation of genetic advances in breeding programs, which allows breeders to make informed decisions, optimize their breeding strategies, and ultimately develop improved varieties more efficiently and effectively [50]. In this study, PCVs ranged from 29.76 (LW) to 197.96 (YA), while GCVs were lower, ranging from 16.15 (MA) to 96.40 (PFW), and ECVs ranged from 19.63 (LP) to 174.37 (YA) (Table 2). Compared with the previous studies, the GCV in FW (77.30) was larger than those found in the studies by Singh et al. (33.48) [42] and Lal et al. (36.42) [51], but heritability was lower (42.84%) than in those studies, accounting for 98.88% and 89.42%, respectively. Additionally, our PCVs of A (126.60), AA (136.09), M (107.87), and MA (115.41) were different from those observed by Lal et al. with A being 125.42, AA being 37.57, M being 162.69, and MA being 88.27, who found higher amounts of triterpenoid saponins but lower amounts of triterpenoid sapogenins. This might result from the strongly significant differences between growing systems and their interactions (Table 1). From Figure 1 and Table 2, it can be seen that plant biomass traits had a higher broad-sense heritability and strongly positive correlations with the yields of phytochemicals. Therefore, we could use plant biomass traits to select plants with higher centelloside yields.

In general, PCA is employed to measure the extent and pattern of variation among different populations, helping to uncover evolutionary trends and the contribution of various factors. Our result showed that only three PCs exhibited over 10% of variances, accounting for 69.29% of the total variability (Table S6). The PCAs of the overall results, on both the combined data across systems and on each cultivation system separately, suggested that plant biomass traits (both FW and DW) were the main traits that could be used to characterize the Centella population, unlike a previous study that categorized their accessions by morphological traits (plant height) rather than biomass [39]. Our genotype vs. traits biplot analysis (GT biplot) distinguished the Asiatic pennywort accessions according to their yields, and concentration of triterpenoid sapogenins (AA and MA) (Figure 3). In addition, the GT biplots of each growing system were used to distinguished accessions based on their yields and concentrations of centelloside (Figure 4).

The clustering pattern of phenotypic traits reveals the connections and similarities between different traits or accessions based on their visible characteristics. It allows for the identification of groups of traits or accessions with similar phenotypic profiles. In this study, four clusters were assembled based on the 29 traits. The purple cluster (Figure 5) was considered as a high potential group for biomass and centelloside yields. Unlike the previous studies that divided accessions based on genotypes in one growing system, we were able to use the hierarchical clustering of each system to determine the high potential accessions for each growing system that would be beneficial for farmers from different growing systems. From this analysis, 10 highest-performing accessions were selected across growing systems from a total of 169 accessions of C. asiatica, namely BB_296, BB_128, BB_98, BB_152, BB_73, BB_143, BB_297, BB_112, BB_127, and BB_110 (Table 3). These elite lines exhibited a higher number of leaves, many long stolons, and large leaves, traits that significantly contributed to higher biomass yields. All selected lines accumulated moderate to high concentrations of centellosides, resulting in the largest centelloside yields. Notably, these lines belong to the green and purple clusters in the dendrogram (Figure 5 or Figure 6A), both characterized by high biomass production and moderate to high centelloside concentrations.

The selection of highest-performing accessions across and within each growing system was also one of the aims of this study. Positive correlations between plant biomass and yields of phytochemicals were observed with different yield-contributing traits such as ML, SL, and LA (Figure 1). Therefore, from the 169 accessions of C. asiatica, 10 lines from each growing experiment were selected based on the yield of total centellosides per plant, which represented a different method from the ones used in a previous study, which selected the elite lines based on the concentration of phytochemical compounds [40].

Since this was the first round of our C. asiatica germplasm evaluation, the research was conducted with a large number of accessions, but under only one environment and with two harvests per growing system. As a result, the genotype-by-environment interactions across multiple years, or diverse agro-climatic zones could not be fully captured. Moreover, seasonal effects, long-term environmental variability, and potential shifts in phytochemical profiles over extended cultivation periods were not assessed. Building on these findings, future research should validate the performance of the selected elite germplasms across multiple locations, seasons, years and growing systems. Expanding evaluations will capture broader genotype-by-environment interactions and ensure stability in both yield and centelloside contents. Such extended research will accelerate the release of improved C. asiatica varieties for both traditional cultivation and commercial-scale applications in the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study constitutes the largest germplasm evaluations of Centella asiatica in Thailand, integrating a direct comparison between soil-based and hydroponic cultivation systems. The evaluation of 169 accessions for morphological, yield-related, and phytochemical traits revealed high phenotypic variability, significant correlations between biomass and centelloside yields, and four distinct genetic clusters, irrespective of cultivation method. These insights not only enable the targeted selection of elite accessions for future breeding programs but also provide an evidence-based foundation for improving yield and quality through optimized cultivation practices. Furthermore, the results offer practical insights for optimizing cultivation strategies, supporting sustainable phytochemical production, and enhancing the quality of medicinal plants in Thailand and beyond.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15171905/s1, Table S1: Origins of 169 accessions of Centella asiatica based on cities and sites in Thailand and nearby countries; Table S2: Trait list and descriptive statistics of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits of Centella asiatica from across and separated growing systems; Table S3: Correlation matrix of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits of Centella asiatica accessions across all environments; Table S4: Correlation matrix of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits of Centella asiatica accessions in soil-based system; Table S5: Correlation matrix of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits of Centella asiatica accessions in hydroponic system; Table S6: Principal component analysis of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits of Centella asiatica accessions across growing systems; Table S7: Principal component analysis of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits of Centella asiatica accessions in soil-based system; Table S8: Principal component analysis of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits of Centella asiatica accessions in hydroponic system; Table S9: Phenotypic data of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits from 10 elite accessions selected across growing systems; Table S10: Phenotypic data of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits from 10 elite accessions selected in hydroponic system; Table S11: Phenotypic data of 29 agro-morphological and phytochemical traits from 10 elite accessions selected in soil-based system.

Author Contributions

J.C., T.K., V.R., T.T. and K.R. conceived of the presented idea and planned the experiment. J.C. and K.R. carried out the phenotypic and yield-related experiment. T.K. performed the chemical profiling analysis. J.C. and K.R. analyzed the data with the assistance from P.T. in Principal component analysis, Euclidean distance and UPGMA dendrogram analysis. J.C. wrote the manuscript in consultation with V.R., P.T., K.R., T.T. and S.W. supervised the project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Innovation for Sustainable Agriculture (ISA) Program (grant number: P-19-51263) and Fundamental Fund 2024 (P-23-51505), National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA), Thailand.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed in the current research are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Foxcroft, L.C.; Henderson, L.; Nichols, G.R.; Martin, B.W. A revised list of alien plants for the Kruger National Park. Koedoe 2003, 46, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, I.E. Centella asiatica (L.) Urban: From traditional medicine to modern medicine with neuroprotective potential. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 2012, 946259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Kharsyntiew, B.; Sharma, P.; Sahoo, U.K.; Sarangi, P.K.; Prus, P.; Imbrea, F. The effect of production and post-harvest processing practices on quality attributes in Centella asiatica (L.) Urban—A review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, P. Centella asiatica in food and beverage applications and its potential antioxidant and neuroprotective effect. Int. Food Res. J. 2011, 18, 1215–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, N.E.; Magana, A.A.; Lak, P.; Wright, K.M.; Quinn, J.; Stevens, J.F.; Maier, C.S.; Soumyanath, A. Centella asiatica—Phytochemistry and mechanisms of neuroprotection and cognitive enhancement. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohil, K.J.; Patel, J.A.; Gajjar, A.K. Pharmacological review on Centella asiatica: A potential herbal cure-all. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 72, 546–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Gautam, A.; Sharma, A.; Batra, A. Centella asiatica (L.): A plant with immense medicinal potential but threatened. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2009, 4, 9–17. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:8531808 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Kunjamon, R.; Johnson, A.J.; Baby, S. Centella asiatica: Secondary metabolites, biological activities and biomass sources. Phytomed. Plus 2022, 2, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjumon, R.; Johnson, A.J.; Sukumaryamma Remadevi, R.K.; Baby, S. Assessment of major centelloside ratios in Centella asiatica accessions grown under identical ecological conditions, bioconversion clues and identification of elite lines. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandopadhyay, S.; Mandal, S.; Ghorai, M.; Jha, N.K.; Kumar, M.; Radha; Ghosh, A.; Proćków, J.; de la Lastra, J.M.P.; Dey, A. Therapeutic properties and pharmacological activities of asiaticoside and madecassoside: A review. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Wu, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qin, L.; Hayashi, M.; Kudo, M.; Gao, M.; Liu, T. Therapeutic potential of Centella asiatica and its triterpenes: A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 568032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, K.; Medikeri, A.; Pasha, T.; Ansari, M.F.; Saudagar, A. Centella asiatica: A traditional herbal medicine. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2022, 15, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbolahan, B.W.; Abiola, A.I.; Kamaldin, J.; Ahmad, M.A.; Atannassova, M.S. Accession in Centella asiatica; Current understanding and future knowledge. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 10, 2485–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, G.H.; Yap, C.K.; Maziah, M.; Tan, S.G. An investigation of arsenic contamination in Peninsular Malaysia based on Centella asiatica and soil samples. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 3243–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, G.H.; Wong, L.S.; Tan, A.L.; Yap, C.K. Effects of metal-contaminated soils on the accumulation of heavy metals in gotu kola (Centella asiatica) and the potential health risks: A study in Peninsular Malaysia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondaland, B.; Khatua, D.C. White rot of Centella asiatica and two weeds in West Bengal, India. J. Crop Weed 2015, 11, 225–226. Available online: https://www.cropandweed.com/vol11issue1/45.html (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Shawon, M.R.A.; Azad, M.O.K.; Ryu, B.R.; Na, J.K.; Choi, K.Y. The electrical conductivity of nutrient solution influenced the growth, centellosides content and gene expression of Centella asiatica in a hydroponic system. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgaud, F.; Gravot, A.; Milesi, S.; Gontier, E. Production of plant secondary metabolites: A historical perspective. Plant Sci. 2001, 161, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Verma, S.; Kushwaha, P.; Srivastava, S.; Rawat, A.K.S. Quantitative estimation of asiatic acid, asiaticoside and madecassoside in two accessions of Centella asiatica (L) Urban for morpho-chemotypic variation. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2014, 48, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.K.; Agrawal, R.K. High performance liquid chromatographic analysis asiaticoside in Centella asiatica (L.) Urban. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2008, 35, 521–525. Available online: https://www.thaiscience.info/journals/Article/TJPS/10576422.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Singh, S.P.; Misra, A.; Kumar, B.; Adhikari, D.; Srivastava, S.; Barik, S.K. Identification of potential cultivation areas for centelloside-specific elite chemotypes of Centella asiatica (L.) using ecological niche modeling. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, A.; Dall’ Acqua, S.; Comai, S.; Innocenti, G.; Jha, P.K. Centella asiatica (L.) Urban from Nepal: Quali-quantitative analysis of samples from several sites, and selection of high terpene containing populations for cultivation. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainol, N.A.; Voo, S.C.; Sarmidi, M.R.; Aziz, R.A. Profiling of Centella asiatica (L.) Urban extract. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2008, 12, 322–327. Available online: https://eprints.utm.my/8639/1/NAZainol2008_ProfilingofCentellaAsiatica.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Hashim, P.; Sidek, H.; Helan, M.H.M.; Sabery, A.; Palanisamy, U.D.; Ilham, M. Triterpene composition and bioactivities of Centella asiatica. Molecules 2011, 16, 1310–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, H.T.H.; Ho, N.T.H.; Ho, H.N.; Nguyen, B.L.Q.; Le, M.H.D.; Duong, T.T. Morphological, phytochemical and genetic characterization of Centella asiatica accessions collected throughout Vietnam and Laos. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 31, 103895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerawitaya, C.; Praseartkul, P.; Taota, K.; Tisarum, R.; Samphumphuang, T.; Singh, H.P.; Cha-Um, S. Investigating high throughput phenotyping based morpho-physiological and biochemical adaptations of indian pennywort (Centella asiatica L. urban) in response to different irrigation regimes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 202, 107927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerawitaya, C.; Pipatsitee, P.; Taota, K.; Praseartkul, P.; Tisarum, R.; Samphumphuang, T.; Singh, H.P.; Cha-Um, S. Impact of irrigation regime on morpho-physiological and biochemical attributes and centelloside content in Indian pennywort (Centella asiatica). Irrig. Sci. 2023, 41, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harakotr, B.; Charoensup, L.; Rithichai, P.; Jirakiattikul, Y. Growth, triterpene glycosides, and antioxidant activities of Centella asiatic L. Urban grown in a controlled environment with different nutrient solution formulations and LED light intensities. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amprayn, K.; Chanchula, N.; Piriyapattarakit, A.; Sunthorn, N.; Premrit, S. Influence of varieties and elicitors on biomass and bioactive compound yield of Centella asiatica growing in Pathumthani. Int. Transact. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttarak, P.; Panichayupakaranant, P. Factors affecting the content of pentacyclic triterpenes in Centella asiatica raw materials. Pharm. Biol. 2012, 50, 1508–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamol, P.; Nukool, W.; Pumjaroen, S.; Inthima, P.; Kongbangkerd, A.; Suphrom, N.; Buddhachat, K. Assessing the genetic diversity of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. and seasonal influence on chemotypes and morphotypes in Thailand. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 218, 118976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asao, T.; Kitazawa, H.; Ban, T.; Pramanik, M.H.R.; Tokumasa, K. Electrodegradation of root exudates to mitigate autotoxicity in hydroponically grown strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) plants. HortScience 2008, 43, 2034–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- de Mendiburu, F. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research; R Package Version 1.3-7; National Agrarian University La Molina: Lima, Peru, 2023; Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=agricolae (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Taiyun, W.; Viliam, S. R Package ‘Corrplot’: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix, Version 0.92. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Popat, R.; Patel, R.; Parmar, D. Variability: Genetic Variability Analysis for Plant Breeding Research, R Package Version 0.1.0. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=variability (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses, R Package Version 1.0.7. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Galili, T. Dendextend: An R Package for Visualizing, Adjusting and Comparing Trees of Hierarchical Clustering, R Package Version 1.19.1. 2015. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/bioinformatics/article/31/22/3718/240978 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Chachai, N.; Pensuriya, B.; Pinsuntiae, T.; Pratubkong, P.; Mungngam, J.; Nitmee, P.; Kaewsri, P.; Wongsatchanan, S.; Jindajia, R.; Triboun, P.; et al. Variability of morphological and agronomical characteristics of Centella asiatica in Thailand. Trends Sci. 2021, 18, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjumon, R.; Johnson, A.J.; Remadevi, R.K.S.; Baby, S. Influence of ecological factors on asiaticoside and madecassoside contents and biomass production in Centella asiatica from its natural habitats in South India. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 189, 115809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.T.; Kurup, R.; Johnson, A.J.; Chandrika, S.P.; Mathew, P.J.; Dan, M.; Baby, S. Elite genotypes/chemotypes, with high contents of madecassoside and asiaticoside, from sixty accessions of Centella asiatica of south India and the Andaman Islands: For cultivation and utility in cosmetic and herbal drug applications. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2010, 32, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.J.; Sane, A.; Thuppil, V.K. Assessment of morphological characterization and genetic variability of Mandukaparni (Centella asiatica L.) accessions. Indian J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2022, 35, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H.L.; Rehman, H. Unravelling the morphological, physiological, and phytochemical responses in Centella asiatica L. Urban to incremental salinity stress. Life 2022, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Pragadheesh, V.; Mathur, A.; Srivastava, N.; Singh, M. Growth and centelloside production in hydroponically established medicinal plant-Centella asiatica (L.). Ind. Crop. Prod. 2012, 35, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Verma, R.K.; Gupta, M.M.; Ram, M.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, S. Screening of genetic resources of the medicinal-vegetable plant Centella asiatica for herb and asiaticoside yields under shaded and full sunlight conditions. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2000, 75, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohini, M.R.; Smitha, G.R. Studying the effect of morphotype and harvest season on yield and quality of Indian genotypes of Centella asiatica: A potential medicinal herb cum underutilized green leafy vegetable. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 145, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Yadav, K.S.; Yadav, N.P.; Mathur, A.; Sreedhar, R.V.; Lal, R.K.; Mathur, A.K. Biomass and centellosides production in two elite Centella asiatica germplasms from India in response to seasonal variation. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 94, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshitila, M.; Gedebo, A.; Degu, H.D.; Olango, T.M.; Tesfaye, B. Study on characters associations and path coefficient analysis for quantitative traits of amaranth genotypes from Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcalde, M.A.; Palazon, J.; Bonfill, M.; Hidalgo-Martinez, D. Enhancing centelloside production in Centella asiatica hairy root lines through metabolic engineering of triterpene biosynthetic pathway early genes. Plants 2023, 12, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyhart, J.L.; Lorenz, A.J.; Smith, K.P. Multi-trait improvement by predicting genetic correlations in breeding crosses. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2019, 9, 3153–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, R.K.; Gupta, P.; Dubey, B.K. Genetic variability and associations in the accessions of Manduk parni {Centella asiatica (L)}. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2017, 96, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).