1. Introduction

Ethiopia has enormous beekeeping potential that makes it the leading honey producer in Africa and one of the top honey producers in the world [

1,

2,

3]. However, this huge potential is not being fully exploited. This is due to various challenges, such as complex value chain arrangements, with several smallholder beekeepers dominated by the conventional system of honey production, and inappropriate value share distribution among the value chain actors [

4,

5]. This requires a detailed analysis of the entire spectrum of the honey value chain with the aim of improving the beekeeping sector’s contribution to the livelihoods of smallholder beekeepers and the country’s economy.

Ethiopia has considerable beekeeping potential to produce 500,000 tons of honey per year due to its diverse agroecological zones, along with rich beekeeping tradition [

1,

3]. However, the country produces only around 10% of its potential, indicating a huge untapped beekeeping capacity. The growing demand for honey and other hive products locally and internationally further increases expansion opportunities [

2,

6]. In addition, Ethiopia has been accredited by the European Union (EU) to export honey to the EU since 2008 [

7]. However, due to various challenges, honey exports account for less than 2% of total production and most honey is consumed locally in the form of local beverages called ‘tej’ (alcoholic honey wine) and ‘birz’ (non-alcoholic honey wine) [

8,

9,

10]. About 80% of honey produced in Ethiopia is used for tej/birz making, which poses a critical challenge to the Ethiopian honey value chain as honey is diverted from high-value markets where processed honey usually generates greater economic returns [

11,

12,

13,

14]. As tej/birz producers do not require high-quality honey, they buy the raw honey at a relatively low price. This in turn restricts the beekeepers’ ability to realize good prices and access premium markets [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Beekeeping in Ethiopia is mainly undertaken by smallholder farmers with conventional—mostly traditional—production systems [

19,

20,

21]. As a result, honey production is highly fragmented, and there are few opportunities to pool the product and process it either for the local market or for export [

22,

23,

24]. Consequently, honey production levels and productivity remain low, therefore, beekeepers benefit little and the country’s foreign exchange earnings from beekeeping remain insignificant [

2,

25,

26]. The development of the honey value chain and its economic potential are also hampered by low productivity and poor quality associated with traditional beekeeping practices, which undermines marketability. Market inefficiencies, characterized by weak linkages, informal trading systems, and price instability that favor middlemen, discourage smallholder beekeepers. In addition, the limited uptake of advanced beekeeping technologies, poor market integration, and uneven distribution of benefits in the value chain hamper the realization of the enormous potential of beekeeping and the benefits that smallholder beekeepers derive from the sector [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Furthermore, inadequate infrastructure, such as transportation, storage, and processing, contributes to less value addition practices and limits access to high-value markets. The sector’s growth and international competitiveness are also hampered by the lack of product standardization, certification systems, and institutional support, despite the country having significant potential for honey production [

32,

33].

Beekeeping is gradually being promoted as a promising alternative for income diversification, environmental protection, rural job creation, and poverty alleviation in low-income countries, including Ethiopia [

34,

35]. However, honey value chain development is still at an early stage, and little is known about the honey value chain configuration as an entry point for development. Therefore, the objectives of this study are to analyze honey value chain stakeholders, their roles, and linkages; quantify the value share of each actor in the chain to determine the position of the actors; and assess the barriers and opportunities of honey production and marketing in southwestern Ethiopia.

The southwestern part of the country is known for its considerable potential for honey production, and thus for honey value chain development, where many households are engaged in honey production for income generation and home consumption. Value chain analysis is essential to explain the connection between all of the actors in the honey production and distribution chain, and it shows who adds value and where along the chain. It helps to identify pressure points and make improvements in weaker links where returns are low [

5,

36]. Understanding the product flow and the value share of actors in the value chain is important to identify opportunities and constraints and to find ways to improve the value chain [

37,

38,

39,

40].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

The Jimma and Kaffa zones in southwestern Ethiopia were selected for this study because they offer great potential for beekeeping. Compared to other parts of the country, beekeeping is extensively practiced in this area, as there are abundant natural forests and biosphere reserves with various flowering plant species and a favorable climate conducive to the settlement of large numbers of honeybees [

11]. Two districts, Gera and Goma from Jimma zone and Gimbo and Shishonde from Kaffa zone, were selected for this study (

Figure 1).

2.2. Data Type, Source, and Sampling Techniques

Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from primary and secondary data sources. Primary data were collected through a formal survey of household heads, honey value chain actors, stakeholders, and beekeeping experts at district and zone levels using pre-tested questionnaires and key informant interview checklists. In addition, focus group discussions (FGDs) and key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted. Secondary data were collected from various reports and databases of government institutions, such as district and zonal agriculture offices.

A multistage sampling procedure was used to select the survey participants and interviewees. In the first stage, three kebeles (the lowest administrative level in Ethiopia) from each district were selected by simple random sampling, assuming that the kebeles have similar production potential because of their similar agroecology. In the second stage, the list of households in each selected kebele was collected, and the household heads were stratified into honey producers and non-producers. Finally, 385 honey-producing household heads were selected by simple random sampling with probability proportional to the number of honey producers in each kebele. In addition, other stakeholders in the honey value chain were also interviewed during data collection.

2.3. Method of Data Collection

The survey data was collected using a structured questionnaire consisting of various modules. The questionnaire was administered by enumerators and supervisors who had local knowledge, spoke the local language, and had previous experience of collecting farm survey data. The enumerators and supervisors were trained on the overall approach of survey data collection procedures, the ethics of data collection, the importance of informed consent, confidentiality, and anonymity, and the contents of the questionnaire. Prior to the actual data collection, the questionnaire was pre-tested on six beekeepers who were not included in the final sample to check the clarity, relevance, and appropriateness of the questions. All necessary modifications were made based on the feedback from the pre-test. Of the total number of 385 questionnaires distributed to the enumerators, 336 were duly completed and returned to the researchers. Of the total number of study participants, 177 were from Jimma and 159 were from Kaffa zone. The majority of the study participants (91%) were male, the average age was 41 years, and the average education level was six grades.

In addition to the beekeepers’ household heads, data were also collected from other stakeholders in the honey value chain using a separate pre-tested questionnaire. Accordingly, 24 collectors, 6 wholesalers, 9 processors, 6 cooperatives, 2 unions, 15 retailers, 4 exporters, and 32 consumers were enrolled for data collection. In addition, 12 focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with purposively selected knowledgeable model beekeepers. Finally, 20 key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted with purposively selected beekeeping experts at federal, zonal, district, and kebele levels, as well as development agents (DAs), to identify the potentials and problems associated with honey production and marketing at the community level. Likewise, both published and unpublished documents were reviewed to collect secondary data.

2.4. Method of Data Analysis

The data collected was analyzed using descriptive statistics, value chain mapping, and value share analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the beekeepers in the sample. The honey value chain map was used to depict the various actors and supporters involved in the honey value chain, their linkages, and the flow of the product and inputs in the study area. The gross profit margin and value share of each actor in the value chain were calculated to determine their performance [

41,

42]. The calculation of the gross profit margin requires information on the various costs incurred and price received by each actor in the value chain [

43,

44]. For this analysis, two homogeneous groups of beekeepers were considered based on their hive types: beekeepers using only traditional hives and beekeepers using improved hives. Since most beekeepers use different types of hives, there are big variations between the study participants in the cost of honey production and the revenue from the honey sold. Apart from beekeepers, other major stakeholders in the honey value chain at the district and zone level, such as collectors, cooperatives, unions, wholesalers, processors, and retailers, were also considered to determine their gross profit margin, added value, and value share.

The gross profit margin measures the efficiency of the actors and pricing strategies. It provides information on how well the actors manage their costs. It is calculated based on the costs and selling price (revenue generated) of each actor for the honey sold (Equation (1)). The added value is the difference between the selling price that the actor receives for the product and the purchase price of the honey by the respective actor [

45,

46,

47]. It is often assumed that the added value for producers is identical to the selling price or the farmgate price. According to [

46], the value share of each actor in the value chain is calculated by determining the price variation at the different actor levels and then comparing it with the final price paid by consumers (retail price) or as added value divided by the consumer price multiplied by one hundred to express it as a percentage (Equation (3)). The value share provides information on the amount that the actors receive from the price paid by consumers. The gross profit margin, the added value, and the value share of a particular actor ‘i’ in the value chain are calculated as follows:

3. Results

Based on the information obtained from the survey and key informant interviews, honey value chain stakeholders, their roles, and linkages were discussed, and a map of the honey value chain was sketched. Then, the profit margin was computed to assess the value share distribution along the chain. Finally, the challenges and opportunities of honey production and marketing were described based on focus group discussions and key informant interviews.

3.1. Main Actors in the Honey Value Chain and Their Key Functions

Input suppliers: Various suppliers provide beekeepers with the inputs needed for honey production. The District Livestock and Fisheries Development Office, research centers, cooperative unions, private traders, and NGOs (non-governmental organizations) are the main suppliers of inputs in the study area. The District Livestock and Fisheries Development Bureau supplies framed box hives (modern hives) and protective equipment to beekeepers in the district when available. Cooperative unions supply modern hives, protective equipment, and honey storage materials to their member cooperatives, which in turn distribute them to their member beekeepers. Private traders supply different types of modern beekeeping equipment to beekeepers. NGOs, such as MOYESH (More Young Entrepreneurs in Silk and Honey), also supply beekeepers with modern equipment to promote the beekeeping sector.

Beehives, protective kits, supplementary feed, and colonies are the most important inputs for beekeepers in the study area. As mentioned in our previous study [

11], 86.5% of traditional hive users construct their hives from locally available materials and 13.5% buy them from the local market. In contrast, 69.4% of transitional hive (e.g., Kenyan top bar hives) users and 46.2% of modern hive users buy from the local market. The results of the FGDs indicate that beekeepers in the Kaffa zone started to construct transitional hives from locally available materials, which is locally called “chefeka.” Beekeepers buy modern hives not only from the local market, but also from governmental organizations (29.9%) and NGOs (18.5%), based on availability.

Of the total number of beekeepers surveyed, 54.2% used protective kits such as gloves, safety clothes, and boots, as well as utensils like smokers and cutting knives. Over 42% of the protective kits were obtained from the local market, while about 28.7% and 27.6% were obtained from NGOs and both the local market and NGOs, respectively (

Table 1). The provision of supplementary feed to bee colonies compensates for the shortage of pollen and nectar and increases bee performance. Of all the households surveyed, only 28% provided supplementary feed to their bees, and 85.2% of them purchased it from the local market. As for the bee colonies, only 6.8% of the respondents bought bee colonies from the local market. The majority (93.2%) of beekeepers catch a swarm of bees from the surrounding forest by hanging traditional hives on tall trees after preparing the hives well by smoking them with good aromatic leaves. Most users of modern hives were transferring a swarm of bees after catching them with traditional hives.

Producers: Smallholder farmers, private investors, and cooperatives are the main honey producers in the study area. They perform most of the functions of the honey value chain, from the procurement of inputs to honey harvesting and marketing. They also carry out activities such as sorting, packaging, and transportation. Honey production, as in other agricultural sectors in the country, is dominated by traditional beekeeping systems and smallholder beekeepers. Of all household heads surveyed, 71% used traditional hives. Of those who use traditional hives, 30% used only traditional hives, while 21% used all three types of hives. However, 13% and 3% of the respondents used only framed box (i.e., modern) hives and Kenyan top bar (i.e., transitional) hives, respectively (

Figure 2). Beekeepers sell their honey mainly to collectors at the local market or on their farmgate to cooperatives, retailers, and consumers.

Collectors: They carry out activities like assembling honey from different beekeepers in rural areas. Both licensed and unlicensed traders collect the crude honey, which is a mixture of honey and beeswax, from the hands of producers at the farmgate or local market and deliver it to wholesalers, retailers, and local processors (tej/birz producers) in the district. These collectors resell the product immediately, as most of them do not have warehouses. The majority of these collectors use motorcycles to reach rural areas without road access, facilitating the transportation of high-quality honey from producers to traders within the district. In addition, some honey producers also perform collection functions by assembling honey from nearby beekeepers and delivering it to the nearest wholesalers or retailers. Cooperatives also collect honey from their members and deliver it to the cooperative unions for further processing and other value addition activities.

Wholesalers: Wholesalers are mainly found in the major towns such as Jimma, Agaro, and Bonga. However, at the district level, some big retailers engage in wholesale, as they hold large quantities of honey, especially during the harvesting season. These actors collect the honey from local collectors and deliver it to retailers and processors at zonal and central markets in Addis Ababa and Adama. The wholesalers maintain close relationships and active communication with their suppliers, such as the collectors and retailers, who receive the honey in bulk for resale. In most cases, wholesalers provide advanced payment to local collectors who do not have sufficient capital.

Primary cooperatives: These are groups of youth and farmers’ associations formed for honey production and marketing. Their leading role in the honey value chain is to produce and assemble the honey produced directly by their members during the harvest season at a better price than the local market and deliver the product to the cooperative union. The primary cooperatives support their members by providing them with inputs. Beekeepers prefer to sell their bee products to their cooperatives because they believe that their scale is reliable and they can benefit from the dividends. When farmers lack capital for various beekeeping activities, the primary cooperatives arrange loans for their members by borrowing money from the unions. As shown in

Table 2, of the beekeepers interviewed, 29% were members of primary cooperatives. The main benefits they obtained from being a member were dividends, marketing services, and capacity building training.

Cooperative unions: This is an association of various primary beekeepers’ cooperatives. The union collects the honey directly from the primary cooperatives. There are two cooperative unions in the study area. The first is the Kaffa Forest Bee Product Development and Marketing Union based in the town of Bonga. This union focuses on activities such as collecting honey from the cooperative members and is involved in processing, wholesaling, retailing, and exporting. The union has 38 main members from whom it regularly collects honey. The cooperative union currently supplies honey and beeswax to local and international markets. In 2021, this union exported 14 tons of processed honey directly to the Germany market. The remaining product was supplied directly to the local market, which can be found throughout the country depending on the demand. For example, the union supplied to wholesalers in Addis Ababa, Adama, and Gonder. The second beekeeping union in the study area is the Kata Muduga Multipurpose Union in Jimma zone, Agaro town, which is mainly involved in coffee production and marketing. However, next to coffee, honey is the second most important product that they market. This union has ten cooperative members who are involved in beekeeping. The union currently supplies honey to the local market in Agaro, Jimma, and Addis Ababa.

Processors: Most of the smallholder beekeepers and cooperatives in the study area sell their honey to buyers in raw form. The processors in the study area are cooperative unions, tej/birz producers (local breweries), and private companies that buy the raw honey from the producers or collectors and add form utility through processing. The unions receive the honey from the primary cooperatives in bulk for further processing and supply the processed honey to the local and global markets. The private honey processors, such as Apinec agroindustry based in Kaffa, and other private honey processors in Addis Ababa and Adama city, such as Beza mar agroindustry and Tutu and his family commercial Plc, buy the honey from wholesalers. They also outsource honey from a group of beekeepers under contract farming arrangements. Finally, they supply the processed honey to both local and international markets. Also, local breweries process the raw honey into ‘tej’ or ‘birz’ and sell it to local consumers, as it is a common drink in all parts of the country.

Retailers: These are the actors who supply the products to the end consumers. In the study area, retailers buy honey from collectors, producers, or wholesalers and sell it to the final consumers. Since honey produced in southwestern Ethiopia is consumed all over the world, local retailers, cooperative union retailers, and global retailers are involved in the final distribution of the honey to consumers. Local retailers also pack the honey for consumers in different-sized packages.

Consumers: Honey is distributed to local and global consumers by various actors involved in the value chain. Local consumers buy raw or processed honey from retailers or producers for final consumption. Local consumers also include the local communities that consume tej/birz from brewery houses. Global consumers are those who buy the exported honey. In the study area, an average of 26 kg of honey is consumed per household per year.

3.2. Main Supporters in Honey Value Chain and Their Key Roles

Regional bureaus and district agricultural offices: They support both the smallholder beekeepers and the cooperatives in the district with honey production and marketing. The district agricultural offices offer technical advice and training for beekeepers. They advise them to use modern beekeeping technologies and move their hives from the forest to the home garden for easier monitoring and management, thus improving the quality and quantity of honey produced in the district. They train them on how to construct a local transitional hive (chefeka hive) from locally available materials. They advise the smallholder beekeepers on honey marketing so that they can sell their products to cooperatives or organize themselves and sell their products in bulk to high-value markets. They also provide technical support and training on beekeeping skills through extension agents.

Research centers: They support beekeepers by providing improved inputs such as seedlings of bee flowers and modern beekeeping equipment. They also provide technical support like training on colony multiplication and queen rearing and provide laboratory services for quality testing, especially for processors and exporters. The Holota Research Center is the best-known beekeeping research center in the country and provides training for beekeepers, as well as experts from different parts of the country. The Jimma Research Center and the Bonga Research Center also support the beekeeping sector in the study area.

Trade and marketing development office: This office plays an important supporting role in coordinating and issuing honey marketing licenses, training marketing professionals, and collecting tax and other regulatory payments from traders. It also assists traders in controlling illegal traders involved in honey marketing and carries out quality control and inspections. In addition, it provides traders with market-related information.

Financial institutions: Microfinance institutions and banks are the main sources of credit services for honey value chain actors when they face a shortage of capital. On one hand, microfinance institutions are the main financial service providers for smallholder beekeepers and small traders like local collectors. On the other hand, for big traders like wholesalers, processors, and exporters, banks are the main source of finance, as these actors have higher working capital requirements than smallholder farmers and traders. Therefore, most large traders receive short- or long-term loans depending on their capital needs; however, they need to present potential collateral to receive the loan. Apart from microcredit and banks, primary cooperatives and unions are also sources of credit for their member beekeepers. Traders also finance their regular honey suppliers when they need a loan.

More Young Entrepreneurs in Silk and Honey (MOYESH): This is an NGO that aims to create jobs and generate income for the youth, taking into account that 60% of them are women, by equipping the youth with appropriate skills and abilities to run their own beekeeping business. It provides beekeeping equipment and start-up capital to the target group of youth.

Ethiopian Honey and Beeswax Producers and Exporters Association (EHBPEA): This promotes the production and export of high-quality and safe bee products by improving marketing regulations and quality standards for beekeeping inputs and packaging materials. It also promotes the exchange of information, experience, and capacity building. It also plays a key role in strengthening commercial beekeeping farms and facilitating market linkages between exporters and producers for a niche market with a premium price.

Cooperative unions: The unions support their member primary cooperatives in different ways, like providing various types of beekeeping materials and equipment, granting loans, and delivering training in the form of training-of-trainers and for its administrative members.

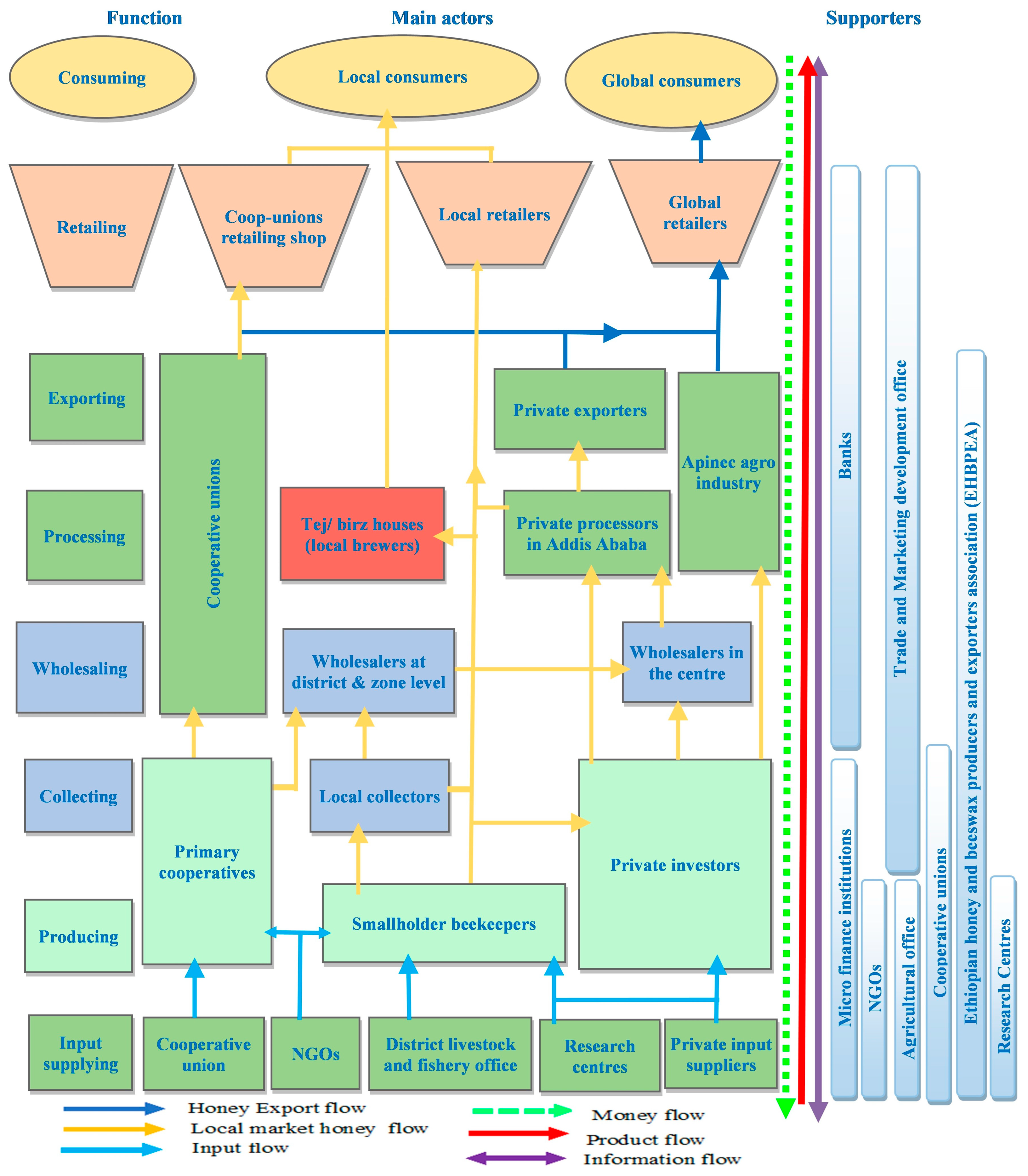

3.3. Honey Value Chain Map in Southwest Ethiopia

Value chain mapping is the visual depiction of all actors involved in the honey value chain, such as key actors and supporters. It also shows how these actors are interconnected and how the product flows from one actor to the next, from the supply of raw materials to the delivery of the products to consumers, as shown in

Figure 3.

3.4. Honey Production Costs and Value Share of Major Honey Value Chain Actors

The cost of honey production is computed based on two homogeneous groups of beekeepers using only traditional hives and improved hives, where the latter refers to beekeepers using Kenyan top bar hives, formed box hives, or both types of hives.

Table 3 presents the cost of honey production for the two categories of beekeepers. The total cost of production for traditional and improved hive users was ETB 123 and 2131.5/hive on average, respectively, and the cost per kg of honey was ETB 11.2 and 88.8/kg, respectively, with an average honey yield of 11.0 kg per traditional hive and 24.0 kg per improved hive. The gross profit margin and the value share of the actors in the honey value chain were calculated based on the average purchase price, the cost of honey sold, and the average selling price of each actor in the study area.

Table 4 shows the summary of the gross profit margin, added value, and value share of the actors in the honey value chain. Traditional- and improved-hive-user beekeepers obtained the highest gross profit margin of 85.9% and 44.3%, respectively. This indicates that the traditional hive users are more cost efficient, as they can easily procure or prepare the traditional hives and have no cost of supplementary feed for their colonies since they keep their hives in the forest, however, they are less productive. However, the beekeepers using improved hives had higher costs due to the high price of the improved hives and their accessories, as well as the supplementary feed for their colonies and their management activities, but they are highly productive. Wholesalers had the highest gross profit margin of 39.1%, next to beekeepers, while retailers had the lowest gross profit margin of 4.3%, compared to the other actors. Improved-hive-user beekeepers obtained the highest added value of ETB 176/kg, followed by wholesalers with ETB 133/kg. In contrast, traditional hive users realized ETB 130/kg. Therefore, the beekeepers using improved hives had the highest value share of 51%, but the beekeepers using traditional hives had a value share of 37.7%. This could be due to the difference in the quality of honey from the two systems and their target market, as it affects the price. Wholesalers had the second highest value share of 39.6%, after beekeepers using improved hives.

In addition, unions, processors, retailers, collectors, and cooperatives had a value share of 29%, 23.2%, 11.6%, 9%, and 7.2%, respectively. Cooperatives had the lowest value added and value share, which is due to the fact that they mainly focus on supporting their member beekeepers rather than making profits. However, the unions achieved a higher value added and value share than the cooperatives, which could be due to the fact that they hold the products in large quantities and add value to their products before selling them, as they are also involved in activities like processing, transportation, storage, sorting, or grading. Also, the unions are likely to take advantage of better markets.

3.5. Constraints and Opportunities in Honey Production and Marketing

The identification of constraints and opportunities is the most important point of any value chain analysis to identify bottlenecks and potentials that would be obstacles or possible solutions to improve the value chain. Based on the information collected during the household surveys, the summary of beekeepers who responded “yes” to the constraints affecting beekeepers in honey production is presented in

Table 5. The results of this study show that the major bottlenecks in honey production in the study area are mainly related to the affordability and availability of modern beekeeping equipment like framed box hives and their accessories, such as protective kits. The other serious problems affecting honey production are related to pests and predators attacking the bees and damaging the hives, especially the traditional hives placed in the forest canopy. The unsafe use of agrochemicals that kill the bees, especially during nectar collection, and problems related to the shortage of modern hive management skills, practical beekeeping training, and access to credit are other challenges affecting beekeepers. Moreover, during the key informant interviews with big processors and exporters, they strongly raised the concern that there is a shortage of internationally accredited laboratories for testing the quality of honey in the country.

Table 6 summarizes the challenges in honey marketing based on the data collected in the household surveys. The major bottlenecks in honey marketing in the study area were related to the shortage of packaging and storage facilities to preserve and protect the quality of the product and reduce post-harvest losses during storage or transportation. More than 80% of beekeepers in both study zones replied that the lack of packaging and storage material is the top honey marketing problem. Low honey price and weak market linkage were the other critical marketing problems that affected beekeepers’ benefits. The beekeepers also indicated that the lack of business support, weak bargaining power, shortage of market information, and lack of transportation facilities such as good roads and high transportation costs were some of the bottlenecks for honey marketing in the study area.

According to the information obtained from the FGDs and KIIs, there are numerous opportunities that support the development of the beekeeping sector in the study area. The main opportunities are the existence of conducive agroecology for beekeeping because of the presence of natural forests (biosphere reserve) such as Yayu, Kaffa, and Sheka biosphere reserves with abundant water and bee flora species; increasing national and international demand for honey; support from non-governmental development partners; and the possibility to practice beekeeping alongside other agricultural activities. Beekeeping is a good source of income and provides employment opportunities for youth, women, and other community members. It generates income without destroying the habitat, rather through preserving biodiversity. It can also be practiced by people with limited resources, such as land and start-up capital, as it does not require owned land or high investment, as the hives can be placed anywhere and do not require fertile land. Compared to most rainfed agricultural activities, which mostly only generate income once a year, beekeeping generates income multiple times (two to three times) a year.

4. Discussion

In the agricultural value chain, access to quality inputs at the right time and affordable prices helps to increase the production and productivity of beekeepers, which raises the living standard of the local community by improving their income [

48,

49,

50]. Beehives, supplementary feed, and protective packages such as protective clothes, gloves, boots, and smokers are the most important inputs for beekeepers in the study area. Most of the smallholder beekeepers who used traditional hives constructed their hives themselves from locally available materials without incurring any costs other than their own labor. Other studies conducted in Ethiopia [

2,

15,

51] and other African countries like Ghana by Jeil, Segbefia et al. [

52], and in Zambia by Lowore [

53], reported that beekeeping is dominated by conventional or traditional systems that require relatively low production costs. However, a modern beekeeping system requires initial capital, which is used to purchase various inputs. In addition, modern beekeeping requires more management skills compared to conventional beekeeping. This could be one of the main reasons why the beekeeping sector in the country in general, and in the study area in particular, remains dominated by traditional systems. This result is in line with the findings of Gratzer, Wakjira et al. [

2], Sahle, Enbiyale et al. [

54], and Tullu [

55].

Smallholder producers, private enterprises, and cooperatives are the most important actors in the production of honey. Beekeeping is among the main sources of annual income; however, it is a part-time activity for smallholder beekeepers. They keep bees beside crop production, livestock rearing, and other non-agricultural activities. This could be an indicator that the traditional beekeeping system does not need intensive follow-up and management, where farmers put their hives on the tree and check whether the colony moves into them and then just go back to the place for harvesting. Conversely, improved beekeeping systems necessitate rigorous and continuous monitoring, including hive inspections and other managerial interventions. Despite the increased labor demands, these modern systems are considerably more rewarding than traditional methods, owing to their significantly higher productivity per hive. The findings of the studies conducted by Kassa Tarekegn [

56] and Nega and Mamo [

57] in Ethiopia and the study conducted by Wambua [

58] in Kenya are consistent with our results. Moreover, despite their low productivity and low honey quality, traditional beehives are used to catch a swarm from the surrounding forest. Even most users of improved hives transfer the swarm after catching it with traditional hives. This shows that the traditional practices and cultural knowledge are integrated with and linked to the modern system, which is very important for sustainability.

Smallholder beekeepers in Ethiopia predominantly engage in the sale of unprocessed honey, lacking value addition, which limits their potential income. In contrast, private investors either process the honey independently or sell it to processors and wholesalers who subsequently supply exporters. Although collectors pay producers a lower price for honey than other actors, they play a crucial role by transporting honey from remote or inaccessible areas to urban centers.

The existing testing laboratories are not well developed, and their testing capacity is limited as they are not internationally recognized. There is only one quality testing laboratory at the Holeta Research Center. Therefore, they mostly send their honey samples to different European countries, such as Germany and Norway, to have the quality of their honey tested, which leads to additional costs that may be elevated as they pay in foreign currency. This could be one of the main reasons for the lower amount of honey supplied to the international market. The same finding was reported by the work carried out by GIZ [

7] in Ethiopia and by Budhathoki-Chhetri, Sah et al. [

59] in Nepal.

Three types of retailers are involved in the honey value chain: local retailers, cooperative retailers, and global retailers. The local retailers, found in both study areas, buy honey directly from the producers and collectors and then deliver it to local consumers and visitors from different parts of the country passing through the respective town. They sort the honey according to its quality and color and pack it in different-sized packages. The local retailers sell both processed and unprocessed honey to the end users. The cooperative retail stores are owned by the unions and sell the processed honey to consumers in the same way as the local retailers. The global retailers buy the honey from the exporters and sell it to international consumers under their own brand names. One of the main problems identified during the key informant interviews with honey retailers in the study area was that there are no clear set standards or criteria to be followed. Therefore, during the honey harvesting season, when there is a large supply in the market, different individuals are involved in honey marketing as collectors and retailers. In most cases, stores that sell other products also sell honey, which could affect the quality of the honey due to its hygroscopic nature. Other common practices that affect the quality and quantity of honey include the use of extra smoke when harvesting from traditional hives. This affects the smell and flavor of the honey. All types of hive products are mixed during harvesting, as it is not easy to separate pure honey from other hive products with the available equipment.

The adulteration of honey was another important issue raised in the focus group discussion and the key informant interviews conducted with traders. Some irresponsible honey traders mix honey with adulterants such as sugar, melted candy, corn or wheat flour, bananas, and sweet potatoes. These adulterations affect the quality and authenticity of the honey, which also decreases the demand at a local and global level. It could also hurt consumer health and trust. The report of Damto [

60] provides an overview of honey adulteration and detection procedures in Ethiopia, which underscores the relevance of the issue. In a similar vein, Mukaila, Falola et al. [

61] reported that there is a serious problem of honey adulteration in Nigeria.

Effective actors in the value chain are always supported by stakeholders outside of the chain who enable the activities of the main actors. Value chain actors continuously need different technical support and market access. The value chain supporters play an important role in facilitating and ensuring the smooth functioning of the chain actors, but they do not take ownership of the commodity. Regional and district agricultural offices, research centers, trade and marketing development offices, financial institutions such as banks and microfinance institutions, and NGOs such as More Young Entrepreneurs in Silk and Honey (MOYESH) and the Ethiopian Honey and Beeswax Producers and Exporters Association (EHBPEA) are some of the major supporters of the honey value chain in the study area. This result supports the findings reported by Kassa Tarekegn [

56], Beyene [

62], and Tullu [

55]. These honey value chain supporters play a crucial role in addressing sectoral challenges and promoting sustainable growth. NGOs contribute through capacity building, supporting cooperatives, and improving access to markets, inputs, and finance, while promoting modern beekeeping to enhance quality and quantity, value addition, and market integration. The private sector invests in infrastructure such as storage and processing, and governments facilitate export promotion through supportive measures, extension services, and quality regulations, such as certification and traceability. Collectively, these actors promote development goals such as improved livelihoods through employment generation, especially for women and youth, gender equality, climate change resilience, and community empowerment.

The actors in the honey value chain add value to the product as the honey moves from one actor to the next. The gross profit margin of the actors was calculated based on the costs they incurred and the revenue generated from the sale of the product. The highest marketing costs were incurred by the retailers, followed by the unions and the processors. Retailers also had the highest total costs, followed by processors and unions, as they mostly pay the highest purchase price for honey. The gross profit margin of wholesalers was the highest compared to retailers, processors, and unions, which is due to the lower purchase price and marketing costs, resulting in lower total costs. The beekeepers using traditional hives had the lowest total cost and the highest gross profit margin, followed by the users of improved hives and the wholesalers. However, their value share is lower than that of beekeepers using improved hives and wholesalers, which is in line with results of the study conducted in Zimbabwe by Mwandifura [

63]. This could be due to the fact that most beekeepers in the study area use a traditional system of beekeeping, which requires lower production costs and low marketing costs, as they mostly sell their product at the farmgate at low prices. A study conducted by Arage [

64] reported that beekeepers earned the second highest gross profit after processors, whereas the highest marketing costs were incurred by retailers, followed by processors.

Although they achieved a lower gross profit margin compared to traditional hive users, beekeepers using improved hives achieved the highest value share, followed by wholesalers. This means that the proportion of the total price paid by consumers that goes to beekeepers with improved hives is higher than for traditional hive users and other intermediaries. Of all the intermediaries, the highest proportion of the price paid by consumers goes to wholesalers, unions, and processors, respectively, from highest to lowest. This is mainly due to the fact that wholesalers add value to the product by creating place utility using transportation, while unions and processors mainly add value to the product by refining the raw and semi-processed honey into table honey, also known as creating form utility via processing. Furthermore, the disparity of the value share could also be due to the bargaining power of the actors, differences in access to market information, the possibility of value addition, and the strength of market linkage. To achieve a more equitable distribution of value, it is, therefore, important to address these power imbalances through collective action, transparent pricing, and inclusive value chain governance.

There were various barriers to honey production and marketing in the study area. The major honey production challenges in Jimma and Kaffa areas were related to beekeeping inputs such as the high cost of modern hives and their accessories and the limited supply of modern hives and beekeeping accessories such as safety clothes, gloves, smokers, cutting knives, and boots. Other serious barriers were honeybee pests and predators, absconding, uncontrolled use of pesticides and herbicides that pose a threat to bee colonies, and the shortage of proper knowledge on the management of modern hives. These problems could be some of the main reasons why the majority of beekeepers rely on the traditional system of beekeeping, which is the main reason for the low contribution of the sector to the livelihood of local beekeepers, as well as to the country’s economy. The study results of Benyam, Yaregal et al. [

65], Beyene [

62], and Kassa Tarekegn [

56] from Ethiopia and the study of Ghode [

66] conducted in India also reported various challenges related to the accessibility of modern beekeeping equipment.

A lack of packaging and storage facilities, low farmgate prices, weak linkages between producers and honey buyers, a lack of support for beekeepers, weak bargaining power of producers, and a lack of market information are some of the major constraints to honey marketing in the study area. Both zones had almost similar marketing and production challenges. This result is consistent with the findings of the review article by Goshme and Ayele [

33] conducted in Ethiopia and the study by Berem [

67] conducted in Kenya. The most important opportunities for beekeeping were the existence of natural forests and biosphere reserves registered under UNESCO, such as the Kaffa and Yayu biosphere reserves, which have abundant water and bee forage resources. Beekeeping helps to increase the production and productivity of flowering plants and crops, as honeybees play a major role in pollination and ecosystem maintenance; moreover, beekeeping is among the main sources of income with less investment and creates gender-inclusive employment opportunities, particularly in the case of modern beekeeping systems.