Social Capital Heterogeneity: Examining Farmer and Rancher Views About Climate Change Through Their Values and Network Diversity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Social Capital and Farmer Responses to Climate Change

“Addressing these knowledge gaps will involve interpretivist perspectives to build on the positivist ways of thinking about social capital and resilience that currently dominate.”[38]

3. Methods: Data Collection, Coding, and Analysis

| Characteristics * | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 20 |

| Hispanic, Latino/a, Spanish Origin | 10 |

| More than one | 5 |

| Black or African American | 5 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Other/Prefer not to share | 0 |

| Gender | |

| Man | 19 |

| Woman | 22 |

| Nonbinary or Genderqueer | 0 |

| Other/Prefer not to share | 0 |

| Age | |

| 21–30 | 6 |

| 31–40 | 14 |

| 41–50 | 14 |

| 51–60 | 6 |

| 61–70 | 1 |

| Farm Size, Acres (owned, leased, and rented) | |

| <25 | 8 |

| 25–100 | 6 |

| 101–300 | 3 |

| 301–600 | 8 |

| 601–900 | 10 |

| 901–1200 | 6 |

| Market Type | |

| Direct-to-consumer | 20 |

| Direct-to-market | 20 |

| Both | 1 |

| Commodities, for sale | |

| 1–3 | 14 |

| 4–6 | 9 |

| 7–9 | 10 |

| More than 10 | 8 |

| Commodities, type, for sale (select all that apply) | |

| Wheat | 14 |

| Alfalfa | 11 |

| Beef | 9 |

| Potatoes | 6 |

| Hay | 5 |

| Millet | 4 |

| Quinoa | 3 |

| Mutton | 3 |

| Dairy | 3 |

| Sweetcorn | 3 |

| Apples | 2 |

| Peaches | 2 |

| Eggs | 2 |

| Grapes | 1 |

| Management-type (select what best applies) | |

| Conventional | 21 |

| Organic, certified | 17 |

| Organic non-certified | 2 |

| Biodynamic, certified—organic certification with additional biodynamic principles | 1 |

4. Results

4.1. Co-Occurrences: Risks and Values

“When someone says, ‘climate change,’ they are thinking ‘more government.’ That concerns me because what that means is higher prices, more paperwork, bureaucracy, and lower profitability.”(Farmer #3)

“I think the biggest threat to agriculture are politicians who believe in climate change. If they had their way, they’d put people like me out of business by regulating us to death.”(Farmer #33)

“People say farmers are selfish and only care about making a profit. Well, I do have to make sure my operation stays in black. If I don’t make money, my family doesn’t eat. So, I do care about running a profitable ranch. I guess that makes me a bad person because I don’t place the needs of polar bears or future generations ahead of my family’s needs like some crazy environmentalist.”(Farmer #11)

“There has to be a societal response to climate change because, hello, it’s not called ‘global’ climate change for nothing. I don’t get those who say farmers need to be left alone [e.g., minimum government regulation]. Leaving us [farmers] alone is what got us into this mess. People who say they cherished freedom as just looking for excuses to be selfish”(Farmer #21)

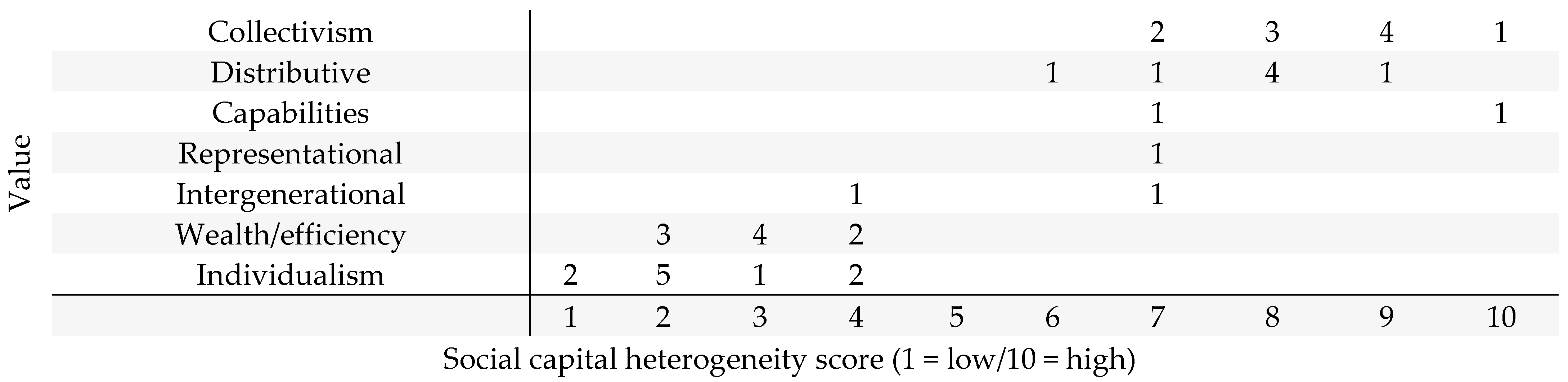

4.2. Value Prevalence and Social Capital Heterogeneity

“I have family members who refuse to interact with anyone who doesn’t think like they do. I’m nothing like that. Do I embrace diversity or choose to live in an echo chamber? Of those two camps, I’m in the former. I believe in hearing from different viewpoints and backgrounds.”(Farmer #40)

“You can’t do this and not be comfortable around ‘people of all stripes’ [a North American saying to refer to people with diverse backgrounds]. […] If you’re not okay engaging with people different from yourself, then you probably should stop trying to sell directly to consumers.”(Farmer #22)

“Farmer’s markets are more than transactional spaces. You’re not just exchanging money for food. They’re relational, where you’re getting to know people and they’re getting to know you. […] If you’re not open-minded, if you come across as a know-it-all or bigoted, word spreads and you’ll fail. […] Those spaces open your world by helping you connect with people you’d never otherwise connect with.”(Farmer #34)

“I’ve been concerned about equity and sustainability since I was old enough to think about those issues. […] It was a given, me becoming an organic, urban farmer dedicated to food and social justice.”(Farmer #28)

“Ask my parents, I wanted to turn our [farming] operation into an organic farm since I was a kid. […] When I finally got old enough to make the call, we started the transition [to eventual organic certification].”(Farmer #1)

“No one seems to care about us [white farmers] anymore. […] Not only do our voices not seem to count, but it feels like the public is hostile to our way of life. […] Look at all the money, like zero-interest loans and grants, going to minority farmers. How is that fair? I’d like some free money, too.”(Farmer #16)

“Think of all the laws and regulations out there that negatively impact people like me, a hardworking, tax-paying American. […] Meanwhile, our government is giving food stamps to illegal immigrants and spending money to take land out of production agriculture, so that people in the city can have their green space. […] You know who comes up with those policies, folks who haven’t a clue what it takes to make it out here; someone who’s never stepped foot on a real farm.”(Farmer #11)

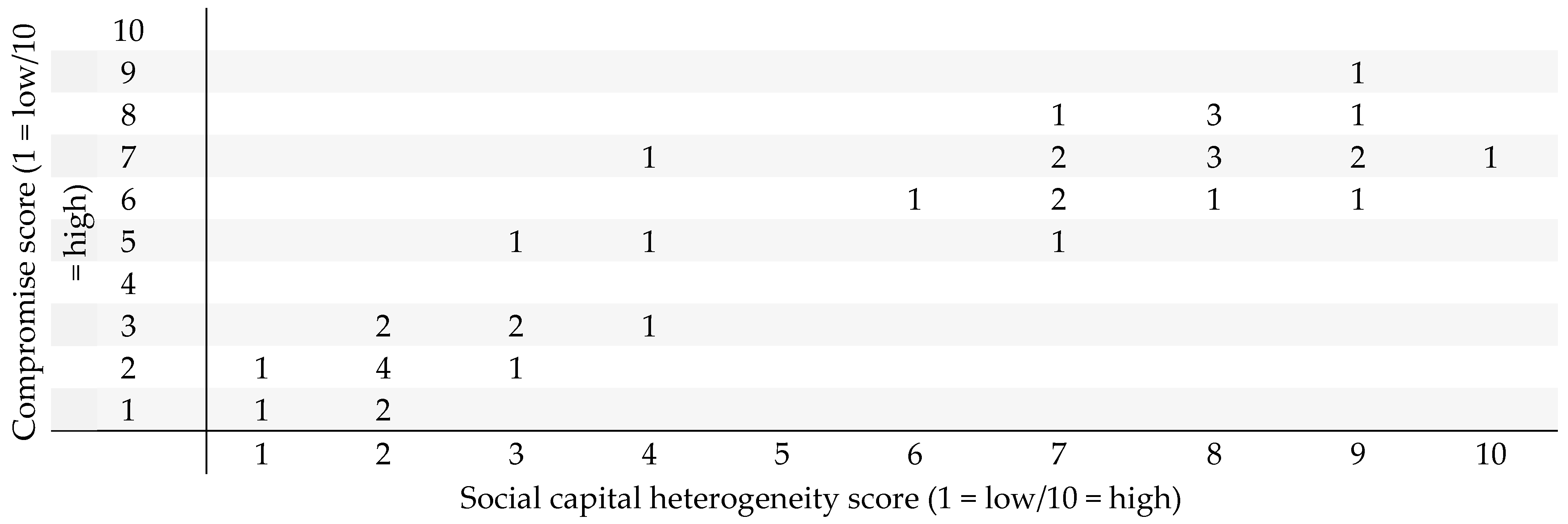

4.3. Governance and the Capacity to Compromise

“I’m all about compromise, but that doesn’t mean I’m open to compromising with a Nazi, white supremacist.”(Farmer #31)

“I interact with all types of people: young and old, different educational levels, sexual orientations, races, religions, Democrats and Republicans, different class backgrounds. […] I interact with all sorts of people because I’m comfortable doing so.”(Farmer #22)

“As I said earlier, I can’t run a successful business if I’m just interacting with people that look, think, and pray like me. When you interact with a lot of people, you inevitably develop some acuity to different viewpoints, which all feeds into some level of willingness to compromise.”(Farmer #22)

4.4. Perceptions of Climate Change Responsibility

“Because we’re seeing less snowpack [in recent years compared to years past] doesn’t mean it’s because of anything humans have done. Climate changes. That’s what it does. […] As part of a natural cycle, we’re shooting ourselves in the foot by taking steps [that reduce GHG emissions] that increase costs while lowering production.”(Farmer #13)

“The notion that man is responsible for climate change is a bunch of hooey [North American slang for ‘nonsense’]. Everyone I know knows it’s [climate change] a load of crap.”(Farmer #25, my emphasis)

“The more I interact with people across the food system in our state, from food activists in Denver dealing with food access issues to potato growers grappling with water shortages or dairy farmers worried about temperature extremes and zoonotic disease, the more I realize we’re in this together. Once you see that, you appreciate the need for a collective response to climate change.”(Farmer #6)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardón, M.; Potter, K.M.; White, E., Jr.; Woodall, C.W. Coastal carbon sentinels: A decade of forest change along the eastern shore of the US signals complex climate change dynamics. PLoS Clim. 2025, 4, e0000444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Kaur, M.; Kaushik, P. Impact of climate change on agriculture and its mitigation strategies: A review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Huang, S.; Chen, H.; Ao, X. Impacts of global climate change on agricultural production: A comprehensive review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Awada, T.; Shi, Y.; Jin, V.L.; Kaiser, M. Global greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture: Pathways to sustainable reductions. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugrahaeningtyas, E.; Lee, J.S.; Park, K.H. Greenhouse gas emissions from livestock: Sources, estimation, and mitigation. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2024, 66, 1083–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hong, M.; Zhang, Y.; Paustian, K. Soil N2O emissions from specialty crop systems: A global estimation and meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soubry, B.; Sherren, K.; Thornton, T.F. Are we taking farmers seriously? A review of the literature on farmer perceptions and climate change, 2007–2018. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 74, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierros-González, I.; López-Feldman, A. Farmers’ perception of climate change: A review of the literature for Latin America. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 672399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asplund, T. Communicating Climate Science: A Matter of Credibility: Swedish Farmers’ Perceptions of Climate-Change Information. Int. J. Clim. Change 2018, 10, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricart, S.; Castelletti, A.; Gandolfi, C. On farmers’ perceptions of climate change and its nexus with climate data and adaptive capacity. A comprehensive review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 083002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talanow, K.; Topp, E.N.; Loos, J.; Martín-López, B. Farmers’ perceptions of climate change and adaptation strategies in South Africa’s Western Cape. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidoo, D.C.; Boateng, S.D.; Freeman, C.K.; Anaglo, J.N. The effect of smallholder maize farmers’ perceptions of climate change on their adaptation strategies: The case of two agro-ecological zones in Ghana. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldulaimi, S.H.; Abu-AlSondos, I.A.; Noun, R.; Abdeldayem, M.M. Navigating sustainability: A comparative analysis of SDG performance in the GCC through the lens of social capital theory. J. Manag. World 2025, 2025, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.P.; Hayes, L.; Wilson, R.L.; Bearsley-Smith, C. Harnessing the social capital of rural communities for youth mental health: An asset-based community development framework. Aust. J. Rural Health 2008, 16, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meikle, P.; Green-Pimentel, L.; Liew, H. Asset accumulation among low-income rural families: Assessing financial capital as a component of community capitals. Community Dev. 2018, 49, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pender, J.L.; Weber, B.A.; Johnson, T.G.; Fannin, J.M. (Eds.) Rural Wealth Creation; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kyne, D.; Aldrich, D.P. Capturing bonding, bridging, and linking social capital through publicly available data. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2020, 11, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agger, A.; Jensen, J.O. Area-based initiatives—And their work in bonding, bridging and linking social capital. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 2045–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogues, T. Social networks near and far: The role of bonding and bridging social capital for assets of the rural poor. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2019, 23, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, D.B. Homophily, selection and socialization in adolescent friendships. Am. J. Sociol. 1978, 84, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifan, L.J. The rural school community center. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1916, 67, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Wacquant, L.J.D. An Introduction to Reflexive Sociology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone the Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. The network structure of social capital. Res. Organ. Behav. 2000, 22, 345–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- DellaPosta, D. Bridging the Parochial Divide: Outsider Brokerage in Mafia Families. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 114, 102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M.; Hale, J. “Growing” communities with urban agriculture: Generating value above and below ground. Community Dev. 2016, 47, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcel, T.L.; Bixby, M.S. The ties that bind: Social capital, families, and children’s well-being. Child Dev. Perspect. 2016, 10, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnitsch, K.; Flora, J.; Ryan, V. Bonding and bridging social capital: The interactive effects on community action. Community Dev. 2006, 37, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aida, J.; Hanibuchi, T.; Nakade, M.; Hirai, H.; Osaka, K.; Kondo, K. The different effects of vertical social capital and horizontal social capital on dental status: A multilevel analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargiulo, M.; Benassi, M. Trapped in your own net? Network cohesion, structural holes, and the adaptation of social capital. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Oh, S.M.; Kahng, B. Betweenness centrality of teams in social networks. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2021, 31, 061108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmen, E.; Fazey, I.; Ross, H.; Bedinger, M.; Smith, F.M.; Prager, K.; McClymont, K.; Morrison, D. Building community resilience in a context of climate change: The role of social capital. Ambio 2022, 51, 1371–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnqvist, J.E.; Itkonen, J.V. Homogeneity of personal values and personality traits in Facebook social networks. J. Res. Personal. 2016, 60, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargnino, M. The interplay of online network homogeneity, populist attitudes, and conspiratorial beliefs: Empirical evidence from a survey on German Facebook users. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2021, 33, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.S. So right it’s wrong: Groupthink and the ubiquitous nature of polarized group decision making. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 37, 219–253. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli, M.; De Francisci Morales, G.; Galeazzi, A.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Starnini, M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023301118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglietto, F.; Valeriani, A.; Righetti, N.; Marino, G. Diverging patterns of interaction around news on social media: Insularity and partisanship during the 2018 Italian election campaign. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 1610–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. When justifications are mistaken for motivations: COVID-related dietary changes at the food-health decision-making nexus. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, T.N.; McClean, C.T.; Settle, J.E. Follow your heart: Could psychophysiology be associated with political discussion network homogeneity? Political Psychol. 2020, 41, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. A Decent Meal: Building Empathy in a Divided America; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, A. Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Varshney, A. Populism and nationalism: An overview of similarities and differences. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2021, 56, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofré-Bravo, G.; Klerkx, L.; Engler, A. Combinations of bonding, bridging, and linking social capital for farm innovation: How farmers configure different support networks. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, D.; Fekadu, G. Influence of social capital in adopting climate change adaptation strategies: Empirical evidence from rural areas of Ambo district in Ethiopia. Clim. Dev. 2021, 13, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.; Carolan, M. Framing cooperative development: The bridging role of cultural and symbolic value between human and material resources. Community Dev. 2018, 49, 360–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Liu, R.; Ma, H.; Zhong, K.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y. The impact of social capital on farmers’ willingness to adopt new agricultural technologies: Empirical evidence from China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffre, O.M.; Poortvliet, P.M.; Klerkx, L. To cluster or not to cluster farmers? Influences on network interactions, risk perceptions, and adoption of aquaculture practices. Agric. Syst. 2019, 173, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farm Fresh Directory; Colorado Department of Agriculture: Denver, CO, USA. Available online: https://coloradoproud.com/resources/farm-fresh-directory/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2022 Census of Agriculture; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/AgCensus/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Colorado Legislature 2024. A Snapshot of Colorado Agriculture; Colorado Legislative Council Staff: Denver, CO, USA, 2024. Available online: https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/r23-286_agricultural_economy_in_colorado_0.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. Discovery of Grounded Theory Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist, A.; Sendén, M.G.; Renström, E.A. What is gender, anyway: A review of the options for operationalising gender. Psychol. Sex. 2021, 12, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffelmeyer, M.; Wypler, J.; Leslie, I. Surveying queer farmers: How heteropatriarchy affects farm viability and farmer well-being in US agriculture. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2023, 12, 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bessette, D.L.; Mayer, L.A.; Cwik, B.; Vezér, M.; Keller, K.; Lempert, R.J.; Tuana, N. Building a values-informed mental model for New Orleans climate risk management. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 1993–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, L.A.; Loa, K.; Cwik, B.; Tuana, N.; Keller, K.; Gonnerman, C.; Parker, A.M.; Lempert, R.J. Understanding scientists’ computational modeling decisions about climate risk management strategies using values-informed mental models. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 42, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundidge, J. Encountering “difference” in the contemporary public sphere: The contribution of the Internet to the heterogeneity of political discussion networks. J. Commun. 2010, 60, 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Choi, J.; Kim, C.; Kim, Y. Social media, network heterogeneity, and opinion polarization. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 702–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, D.M.; Braman, D.; Cohen, G.L.; Gastil, J.; Slovic, P. Who fears the HPV vaccine, who doesn’t, and why? An experimental study of the mechanisms of cultural cognition. Law Hum. Behav. 2010, 34, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahan, D.M.; Jenkins-Smith, H.; Braman, D. Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J. Risk Res. 2011, 14, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, H.C.; Varnum, M.E.; Grossmann, I. Global increases in individualism. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, K.; Gifford, R. Psychological barriers to energy conservation behavior: The role of worldviews and climate change risk perception. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 749–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepermans, Y.; Maeseele, P. The politicization of climate change: Problem or solution? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2016, 7, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulas, J.T.; Stachowski, A.A.; Haynes, B.A. Middle response functioning in Likert-responses to personality items. J. Bus. Psychol. 2008, 22, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutyline, A.; Willer, R. The social structure of political echo chambers: Variation in ideological homophily in online networks. Political Psychol. 2017, 38, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, L.; Rollwage, M.; Dolan, R.J.; Fleming, S.M. Dogmatism manifests in lowered information search under uncertainty. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 31527–31534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, J.; Holm, L.; Frewer, L.; Robinson, P.; Sandøe, P. Beyond the knowledge deficit: Recent research into lay and expert attitudes to food risks. Appetite 2003, 41, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturgis, P.; Allum, N. Science in society: Re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Underst. Sci. 2004, 13, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutzer, E.; Hannah, A.L. Teaching climate change in middle schools and high schools: Investigating STEM education’s deficit model. Clim. Change 2018, 149, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, B.B.; Carolan, M.; Hale, J.; Thilmany McFadden, D.; Love, E.; Christensen, L.; Covey, T.; Bellows, L.; Cleary, R.; David, O.; et al. Connecting urban food plans to the countryside: Leveraging Denver’s food vision to explore meaningful rural–urban linkages. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, J. Federal DEI Funding Cuts Threaten the Work of the Few Remaining Black Farmers in East Texas; The Texas Tribune: Austin, TX, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.texastribune.org/2025/07/17/east-texas-black-farmers-donald-trump/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Thakore, I. Trump Administration Cancels Millions in Agriculture Funding for Western States, Including Colorado Ranchers and Farmers; Colorado Public Radio: Centennial, CO, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.cpr.org/2025/07/10/trump-cancels-millions-agriculture-funding/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Klinke, A. Public understanding of risk and risk governance. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Questions |

|---|---|

| Basic Orientation | Tell me about your operation and about what led you to become a farmer/rancher? What are your goals as a farmer/rancher? What opportunities do you see for those in agriculture? And what risks loom on the horizon? |

| Change | In your view, how are food systems likely to change in the next couple of decades? What does this mean for those producing food? What does this mean for agriculture-dependent communities? |

| Uncertainties | Realizing it is impossible to know everything, what uncertainties need to be prioritized and made less uncertain to build sustainable food systems that support human flourishing? |

| Goals | What should our food systems be trying to accomplish? How well do these goals align with current farm/ranch management practices on your operation? |

| Barriers | What are keeping food systems from better serving our needs and goals? And what barriers stand in your way from adopting practices that better serve your goals? |

| Performance Measures | What performance measures could or should be used/created to evaluate whether food systems are living up to our values and meeting our needs and goals? What performance measure do you pay attention to when evaluating your management practices and alternative, yet-to-be-adopted practices? |

| Values | Reflecting on your answers to the prior questions, what values are being prioritized? Discussing values further, describe your positions on topics like equality, inequity, fairness, justice, sustainability, and such? |

| Risks | What are the most significant threats or risks facing our food systems? How does a changing climate shape risk perceptions? |

| Heterogeneity (10-Point Scale) | How strongly do you agree (or disagree) with these statements (1 = “strongly agree”/10 = “strongly disagree”)? My peers and I share the same: (1) political views; (2) religious or spiritual orientation; (3) level of formal education; and (4) list of favorite media (television, print, online) that we turn to for news and opinion. |

| Governance & Compromise (10-Point Scale) | How strongly do you agree (or disagree) with this statement (1 = “always reject”/10 = “always support”)? There is no place for compromise in politics today, and it should be avoided at all costs. Next, answer that question as the average person, in your estimation, would. |

| Missing Concepts | Are there any other concepts, in addition to the ten noted above, that should have been considered in this interview protocol? If yes: explore the concept. |

| Code | Subcode | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Value | Distributive justice | Concern over how material costs and benefits are distributed |

| Representational justice | Decision making is insufficiently inclusive | |

| Precautionary principle | Innovations need to be proven safe before adopted widely | |

| Intergenerational justice | Concerns on how current activities impact future generations | |

| Wealth/efficiency | Privilege wealth creation, market expansion, and scalability | |

| Capabilities/affordances | Individuals are afforded structural capabilities to flourish | |

| Collectivism | Emphasize the importance of societal over individual needs | |

| Individualism | Emphasize individual (over collective) needs | |

| Risk | Changing climate | More weather events at the “tail” of the normal distribution |

| Government regulation | Increasing government oversight | |

| Land availability | Rising land prices, urban sprawl, diminishing arable land | |

| Food prices | Increasing food prices | |

| Resource scarcity | Dwindling (access to) natural resources | |

| Corporatization | Growing corporate control of food systems | |

| Geopolitical uncertainty | International conflicts that disrupt trade/production | |

| Poverty | Rising levels of inequality | |

| Farm profitability | Farmers getting squeezed by buyers and sellers | |

| Population growth | Concerns about production keeping up with demand | |

| Farm lifestyle viability | Concerns family farms/ranches might disappear |

| RISK ALUE | Government Regulation | Poverty | Corporate Concentration | Climate Change | Farm Profit | Resource Scarcity | Land Availability | Geopolitical Uncertainty | Farm Lifestyle | Population Growth | Food Price | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth/efficiency | 42 | 31 | 33 | 12 | 15 | 133 | ||||||

| Individualism | 38 | 16 | 22 | 14 | 8 | 4 | 102 | |||||

| Distributive justice | 8 | 14 | 24 | 12 | 12 | 5 | 11 | 86 | ||||

| Collectivism | 32 | 24 | 14 | 3 | 73 | |||||||

| Capabilities/affordances | 19 | 27 | 4 | 50 | ||||||||

| Intergenerational justice | 15 | 18 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 43 | ||||||

| Representational justice | 4 | 12 | 16 | |||||||||

| Precautionary principle | 8 | 2 | 10 | |||||||||

| Total | 92 | 80 | 79 | 56 | 53 | 50 | 28 | 20 | 17 | 17 | 11 | Total |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carolan, M. Social Capital Heterogeneity: Examining Farmer and Rancher Views About Climate Change Through Their Values and Network Diversity. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15161749

Carolan M. Social Capital Heterogeneity: Examining Farmer and Rancher Views About Climate Change Through Their Values and Network Diversity. Agriculture. 2025; 15(16):1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15161749

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarolan, Michael. 2025. "Social Capital Heterogeneity: Examining Farmer and Rancher Views About Climate Change Through Their Values and Network Diversity" Agriculture 15, no. 16: 1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15161749

APA StyleCarolan, M. (2025). Social Capital Heterogeneity: Examining Farmer and Rancher Views About Climate Change Through Their Values and Network Diversity. Agriculture, 15(16), 1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15161749