From Heritage to Modern Economy: Quantitative Surveys and Ethnographic Insights on Sustainability of Traditional Bihor Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. General Context of Research

1.2. Fundamental Research Objective

1.3. Research Hypotheses

1.4. The Originality of the Research

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Definition of Key Concepts

2.2. Similar Case Studies and Their Relevance

2.2.1. National Case Studies

2.2.2. International Case Studies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Studied Region and Research Adaptation to the Context

3.2. Research Design

3.2.1. Quantitative Component: Consumer Questionnaire

- Socio-demographic profiling—This section collected essential background information to enable segmentation by age, gender, education level, income, and residential environment (urban or rural). Sample question: What is your highest level of formal education?

- Familiarity with specific traditional products from the region—Participants were asked to indicate their knowledge and recognition of various traditional food items specific to Bihor County, such as plăcinte, ciorbe ardelenești, or cozonac cu nucă. Sample question: Have you heard of or consumed any of the following traditional foods in the past year?

- Frequency and context of consumption—This part aimed to understand consumption habits and preferences, including whether traditional foods are part of daily diets or reserved for special occasions. Sample question: How often do you consume traditional dishes (e.g., homemade or locally produced) per month?

- Perceptions of sustainability, product authenticity, and pricing acceptability—Here, respondents were invited to express their views on whether traditional foods are perceived as healthier, more sustainable, or more authentic than industrial alternatives, as well as their willingness to pay a premium. Sample question: To what extent do you agree with the following statement: “Traditional food products are healthier and more environmentally friendly than mass-produced items”?

- Openness to contemporary purchasing methods, such as online platforms, eco-friendly packaging, and regionally branded labels—This section explored attitudes toward digital commerce, sustainable packaging, and labels indicating regional origin. Sample question: Would you be willing to purchase traditional food products online if authenticity and origin were verified?

- Views regarding the potential for wider promotion and international market integration of these food items—respondents assessed the perceived potential for traditional foods from Bihor to be more actively promoted, both nationally and internationally. Sample question: Do you believe traditional food products from Bihor could have a competitive place in international markets if properly marketed?

3.2.2. Qualitative Component: Ethnographic Research Among Producers

- Semi-structured interviews conducted with 20 key actors involved in traditional food production, ranging from culinary artisans and small-scale household producers to market vendors and participants at local festivals;

- Direct, participatory observation carried out in domestic kitchens and production sites, wherever access was granted;

- Visual and narrative documentation aimed at preserving both the tangible and intangible aspects of food-making—recipes, techniques, and the relational dynamics between producers and their customers.

- Sustained participation in the preparation or commercialization of traditional food items;

- Variety in the types of products produced, ranging from savory dishes and baked goods to preserves, cured meats, and regional desserts;

- Openness to dialog and a willingness to reflect on personal experiences, challenges, and knowledge transmission.

3.2.3. The Analysis Model of the Results

3.2.4. The Validity and Limitations of the Research

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Quantitative Analysis

4.1.1. Socio-Demographic Profile of Respondents

4.1.2. Statistical Tests and Interpretation of Results

Pearson Correlation: Level of Awareness vs. Frequency of Consumption

Spearman Correlation: Awareness vs. Willingness to Pay More

t-Test: Willingness to Pay—Urban vs. Rural

ANOVA: Perception of Sustainability—Differences Between Age Groups

4.2. Results of the Qualitative (Ethnographic) Analysis

4.2.1. Analysis of Emerging Themes and Subcategories

- (1)

- Transmission of tradition: between emotion and functionality

“Every dish has its own story. When I cook it, I hear my mother in my mind. I don’t have the recipe written down, but I know it with my hands.”—Female participant, age 71

- (2)

- Production challenges: between effort and helplessness

“I have a cow, but I can’t keep it anymore. Even the grass doesn’t grow like it used to, and the work is harder and harder. They ask us for paperwork at the town hall, and I don’t know how to do it.”—Female participant, age 64

- (3)

- Coopetition and community: from isolation to informal networks

“She has the jars, I have the plums. We put them together. Better both of us than each on our own.”—Female participant, age 58

- (4)

- Openness to digitalization: reluctance and potential

“I don’t know how to use the phone, but my daughter takes pictures and posts them on Facebook. She says that’s how you sell things nowadays.”—Male participant, age 55

- (5)

- Visions of sustainability: between instinct and practice

“I don’t use preservatives. If it keeps, good. If not, that means it was meant to be eaten quickly.”—Female participant, age 61

4.2.2. Visual Representation: NVivo Tree Map

4.2.3. Validation of Hypothesis H3

5. Discussion

5.1. Validation of Research Hypotheses

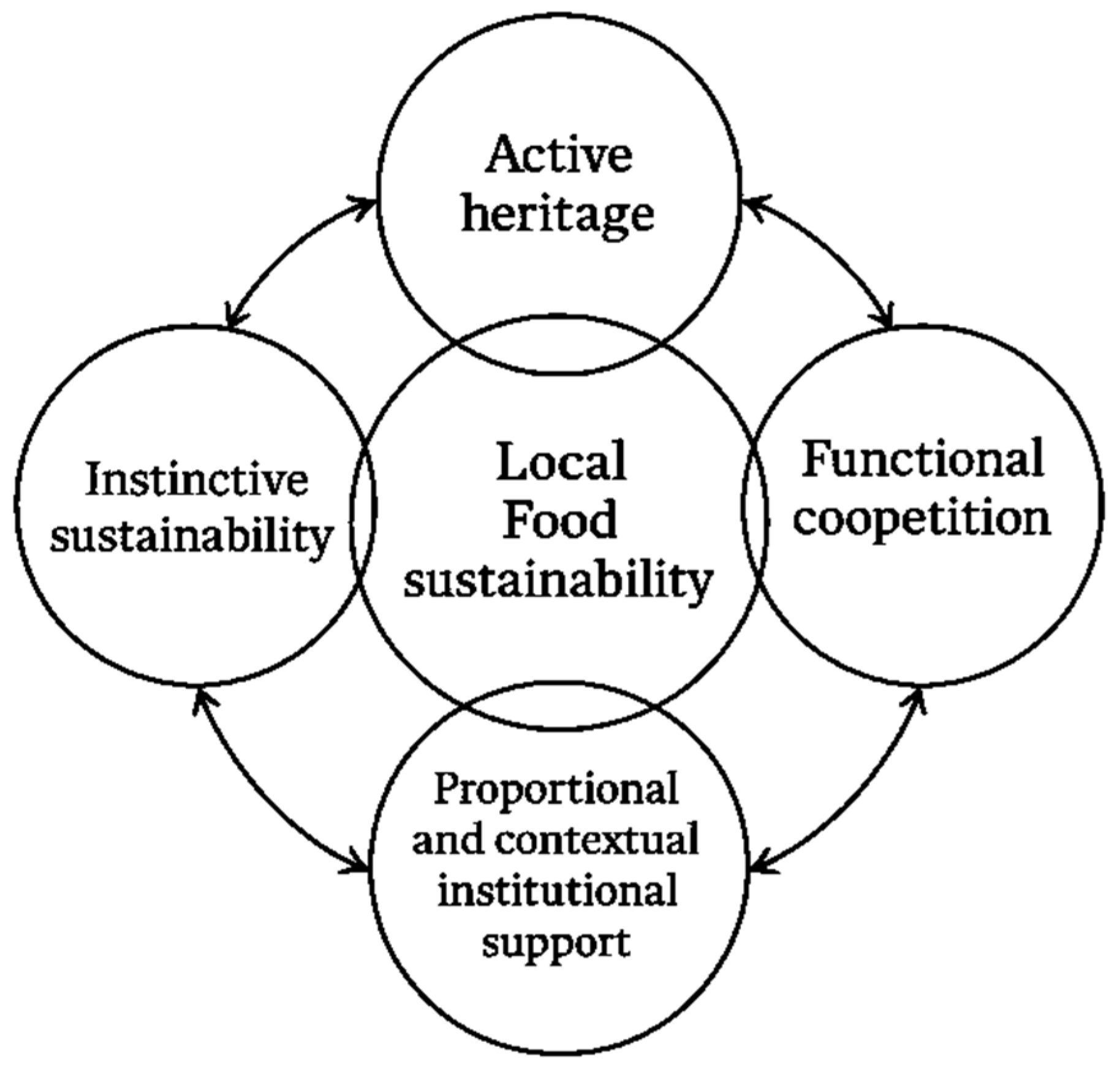

5.2. The Proposed Model of Local Food Sustainability

- (a)

- Active heritage

- (b)

- Functional coopetition

- (c)

- Instinctive sustainability

- (d)

- Local food sustainability

- (e)

- Proportional and contextual institutional support

5.3. Public Policy Proposals and Development Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galanakis, C.M. The future of food. Foods 2024, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillekroken, D.; Bye, A.; Halvorsrud, L.; Terragni, L.; Debesay, J. Food for soul—Older immigrants’ food habits and meal preferences after immigration: A systematic literature review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2024, 26, 775–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobay, K.M.; Apetroaie, C. Sustainable rural development through local gastronomic points. Agric. Econ. Rural Dev. 2024, 21, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, A.V. The transition from industry 4.0 to industry 5.0. The 4Cs of the global economic change. In Proceedings of the 16th Economic International Conference NCOE 4.0, Suceava, Romania, 7–8 May 2020; Editura Lumen, Asociatia Lumen: Iași, Romania, 2020; pp. 70–81. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/chapter-detail?id=971682 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Jayalath, M.M.; Perera, H.N.; Ratnayake, R.C.; Thibbotuwawa, A. Harvesting Sustainability: Transforming Traditional Agri-Food Supply Chains with Circular Economy in Developing Economies. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 11, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajumesh, S. Promoting sustainable and human-centric industry 5.0: A thematic analysis of emerging research topics and opportunities. J. Bus. Socio-Econ. Dev. 2024, 4, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brako, M. Preserving culinary heritage: Challenges faced by Takoradi technical university food service lab students. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Soldato, E.; Massari, S. Creativity and digital strategies to support food cultural heritage in Mediterranean rural areas. EuroMed J. Bus. 2024, 19, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwurah, G.O.; Okeke, F.O.; Isimah, M.O.; Enoguanbhor, E.C.; Awe, F.C.; Nnaemeka-Okeke, R.C.; Guo, S.; Nwafor, I.V.; Okeke, C.A. Cultural Influence of Local Food Heritage on Sustainable Development. World 2025, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A. Competition and cooperation: A coopetition strategy for sustainable performance through serial mediation of knowledge sharing and open innovation. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zan, A.; Zhang, X. Coopetition strategy and innovation performance: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.L.; Truyen, F.; Segers, Y. Safeguarding Savoir-Faire: Culinary Heritage Initiatives, Globalization, and Nationalism in Contemporary France. 2024. Available online: https://lirias.kuleuven.be/handle/20.500.12942/735356 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Balzano, M.; Marzi, G. Osmice at the crossroads: The dialectical interplay of tradition, modernity and cultural identity in family businesses. J. Manag. Hist. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zocchi, D.M.; Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. Recognising, safeguarding, and promoting food heritage: Challenges and prospects for the future of sustainable food systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.; Casabianca, F.; Cerdan, C.; Peri, I. Protecting food cultural biodiversity: From theory to practice. Challenging the geographical indications and the slow food models. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh, H. Conceptualizing the Patterns of Change in Cultural Values: The Paradoxical Effects of Modernization, Demographics, and Globalization. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; Ali, S.A. Preservation of Culinary Heritage and Cultural Tourism: Analysing the Global Impact of Geographical Indication Protection on Cheese Varieties. In Global Perspectives on Cheese Tourism; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 223–240. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/preservation-of-culinary-heritage-and-cultural-tourism/363399 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Yachika, Y. Food as Cultural Diplomacy: Exploring the Role of Cuisine in Global Relations. Siddhanta’s Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2025, 1, 96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality; Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority of the Netherlands. European Food Safety Control Systems: New Perspectives on a Harmonized Legal Basis (Agenda Item 4.2, GF 02/5b); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2004; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/y5871e/y5871e0l.htm (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Bihor Destination Management Agency; Bihor National Center for Tourist Information and Promotion (Eds.) Traditional Recipes from Bihor. Treira; Historical Notes by Prof. Univ. Dr. Aurel Chiriac; Design and Photography by Adrian Samoilă; 2023; ISBN 978-606-657-154-8. Available online: https://www.cjbihor.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Retete-Traditionale-DEBIHOR-RO.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- von Braun, J.; Afsana, K.; Fresco, L.O.; Hassan, M.; Torero, M. Food Systems: Definition, Concept and Application for the UN Food Systems Summit; Center for Development Research (ZEF) in Cooperation with the Scientific Group for the UN Food Systems Summit: Bonn, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/food_systems_concept_paper_scientific_group-draft_oct_261.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Højlund, S.; Mouritsen, O.G. Sustainable Cuisines and Taste Across Space and Time: Lessons from the Past and Promises for the Future. Gastronomy 2025, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.A.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Croitoru, I.M.; Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R. Rural Tourism in Mountain Rural Comunities-Possible Direction/Strategies: Case Study Mountain Area from Bihor County. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Wang, L. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akundi, A.; Euresti, D.; Luna, S.; Ankobiah, W.; Lopes, A.; Edinbarough, I. State of Industry 5.0—Analysis and identification of current research trends. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Sosa, J.; Dextre, M.L.; Vargas-Merino, J.A. Peruvian ceviche: Cultural heritage of humanity and its socio-cultural significance. J. Ethn. Foods 2025, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Zocchi, D.M.; Pieroni, A. Scouting for food heritage for achieving sustainable development: The methodological approach of the atlas of the Ark of Taste. Heritage 2022, 5, 526–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A. Diversity v. globalization: Traditional foods at the epicentre. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 951–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.F.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhang, F.R.; Liu, Y.S.; Cheng, S.K.; Zhu, J.; Si, W.; Fan, S.-G.; Gu, S.S.; Hu, B.C.; et al. New patterns of globalization and food security. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 1362–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitu, S. Traditional Food and Gastronomy in Maramureş. In Passing A Triple Frontier; Chamber of Commerce and Industry Maramures: Baia Mare, Romania, 2021; p. 109. Available online: https://dspace.uzhnu.edu.ua/jspui/bitstream/lib/67364/1/Passing.pdf#page=110 (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Stanciu, M.; Popescu, A.; Stanciu, C.; Popa, S. Local Gastronomic Points as Part of Sustainable Agritourism and Young People’s Perception of It. Case Study, Sibiu County, Romania, 2022. Available online: https://managementjournal.usamv.ro/pdf/vol.22_4/Art74.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Ciliberti, S.; Frascarelli, A.; Polenzani, B.; Brunori, G.; Martino, G. Digitalisation strategies in the agri-food system: The case of PDO Parmigiano Reggiano. Agric. Syst. 2024, 218, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D.; Yeh, C.H.; Cozzi, E.; Arfini, F. Consumer preferences for cheese products with quality labels: The case of Parmigiano Reggiano and Comté. Animals 2022, 12, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garai-Fodor, M.; Popovics, A. Changes in Food Consumption Patterns in Hungary, with Special Regard to Hungarian Food. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2022, 19, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ábrahám, K.; Ferenc, S. Identity, Ethnicity, and Religious Changes in Bihor County, Romania. Reflections on the Changes of Romanian and Hungarian Christian Denominations in Bihor County During the 20th Century. The Case of Érselénd/Șilindru. Stud. Univ. Babes-Bolyai Theol. Reformata Transylvanica 2022, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chivu, M.; Stanciu, S. Promoting Romania’s Culinary Heritage. Case Study: Local Gastronomic Points. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2024, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Adamov, T.; Feher, A.; Stanciu, S. Smart Tourist Village-An Entrepreneurial Necessity for Maramures Rural Area. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Hanif, M.F.; Siddiqui, M.K.; Hanif, M.F. On analysis of entropy measure via logarithmic regression model and Pearson correlation for Tri-s-triazine. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 240, 112994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Heuvel, E.; Zhan, Z. Myths about linear and monotonic associations: Pearson’sr, Spearman’s ρ, and Kendall’s τ. Am. Stat. 2022, 76, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.; Jakicic, V. Equivalent statistics for a one-sample t-test. Behav. Res. Methods 2023, 55, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, L. t-Test and ANOVA for data with ceiling and/or floor effects. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) | Pearson’s r | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness score (1–5 scale) | 4.12 | 0.67 | Weak negative correlation, not statistically significant; awareness does not predict higher consumption frequency | ||

| Frequency of consumption (1–5 scale) | 3.78 | 0.84 | −0.143 | 0.0953 |

| Variable | Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) | Pearson’s r | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness score (1–5 scale) | 4.12 | 0.67 | Weak positive correlation, not statistically significant; awareness may influence appreciation but not payment behavior | ||

| Willingness to pay more (1–5 scale) | 3.54 | 0.91 | 0.138 | 0.1069 |

| Group | N | Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) | t-Value | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban residents | 84 | 3.64 | 0.88 | Marginally significant difference; urban respondents show a slight tendency toward greater willingness to pay more for traditional products | ||

| Rural residents | 53 | 3.39 | 0.95 | 1.845 | 0.0672 |

| Age Group | N | Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) | F-Value | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–35 (young adults) | 44 | 4.08 | 0.72 | No statistically significant differences; perceptions of sustainability are consistent across age groups | ||

| 36–59 (middle-aged) | 63 | 4.15 | 0.69 | |||

| 60+ (seniors) | 30 | 4.11 | 0.66 | 0.981 | 0.3775 |

| No. | Indicator Analyzed | Type of Analysis | Statistical Value | p-Value | Preliminary Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Awareness vs. frequency of consumption | Pearson Correlation | −0.143 | 0.0953 | Weak negative correlation, not significant |

| 2 | Awareness vs. willingness to pay more | Spearman Correlation | 0.138 | 0.1069 | Weak positive correlation, not significant |

| 3 | Urban vs. rural (willingness to pay more) | t-Test | 1.845 | 0.0672 | Moderate difference, marginally significant |

| 4 | Perception of sustainability across age groups | ANOVA | 0.981 | 0.3775 | No significant differences between age groups |

| Main Theme | Subcategories | Total Frq. | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Transmission of tradition | family recipes (20), cooking rituals (18) | 38 | Traditional recipes carry memory and cultural identity |

| 2. Production challenges | raw materials (18), bureaucracy (16) | 34 | Access to resources and bureaucracy limit the continuity of traditional production |

| 3. Coopetition and community | mutual support (17), collective initiatives (15), and local brand (12) | 44 | Informal networks of solidarity and collaboration are emerging among producers |

| 4. Openness to digitalization | social media (15), online orders (14), and technological reluctance (10) | 39 | Digitalization is seen as a means of adaptation, often supported within the family |

| 5. Visions of sustainability | naturalness (14), seasonality (12), and subsistence farming (10) | 36 | Sustainability is experienced instinctively through natural rhythms and seasonality |

| Hypothesis | Formulation | Result | Arguments |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | The level of awareness of traditional products positively influences consumption frequency and willingness to pay | Partially confirmed | Weak positive correlation between awareness and willingness to pay; no significant link with frequency |

| H2 | There are significant differences in the perception of sustainability among consumer groups | Rejected | ANOVA did not identify differences between age groups; sustainability is perceived uniformly across groups |

| H3 | Local producers are open to digitalization and cooperation, while preserving product authenticity | Confirmed | Interviews revealed openness to social media, online orders, and shared branding, with authenticity as a key condition |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bacter, R.V.; Gherdan, A.E.M.; Ciolac, R.; Bacter, D.P.; Dodu, M.A.; Casau-Crainic, M.S.; Gavra, C.; Pereș, A.C.; Ungureanu, A.; Czirják, T.-Z. From Heritage to Modern Economy: Quantitative Surveys and Ethnographic Insights on Sustainability of Traditional Bihor Products. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15131404

Bacter RV, Gherdan AEM, Ciolac R, Bacter DP, Dodu MA, Casau-Crainic MS, Gavra C, Pereș AC, Ungureanu A, Czirják T-Z. From Heritage to Modern Economy: Quantitative Surveys and Ethnographic Insights on Sustainability of Traditional Bihor Products. Agriculture. 2025; 15(13):1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15131404

Chicago/Turabian StyleBacter, Ramona Vasilica, Alina Emilia Maria Gherdan, Ramona Ciolac, Denis Paul Bacter, Monica Angelica Dodu, Mirela Salvia Casau-Crainic, Codrin Gavra, Ana Cornelia Pereș, Alexandra Ungureanu, and Tibor-Zsolt Czirják. 2025. "From Heritage to Modern Economy: Quantitative Surveys and Ethnographic Insights on Sustainability of Traditional Bihor Products" Agriculture 15, no. 13: 1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15131404

APA StyleBacter, R. V., Gherdan, A. E. M., Ciolac, R., Bacter, D. P., Dodu, M. A., Casau-Crainic, M. S., Gavra, C., Pereș, A. C., Ungureanu, A., & Czirják, T.-Z. (2025). From Heritage to Modern Economy: Quantitative Surveys and Ethnographic Insights on Sustainability of Traditional Bihor Products. Agriculture, 15(13), 1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15131404