The Influence of Silage Additives Supplementation on Chemical Composition, Aerobic Stability, and In Vitro Digestibility in Silage Mixed with Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Silage Materials

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Measurement of Chemical Composition and Fermentation Parameters

2.4. Determination of Microbial Count and Aerobic Stability

2.5. In Vitro Incubation Experiment

2.6. Analysis of In Vitro Digestibility and Ruminal Fermentation

2.7. Kinetic Parameter Calculation of In Vitro Gas Production

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition of Mixed Silage Composed of Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw

3.2. Fermentation Parameters of Mixed Silage Composed of Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw

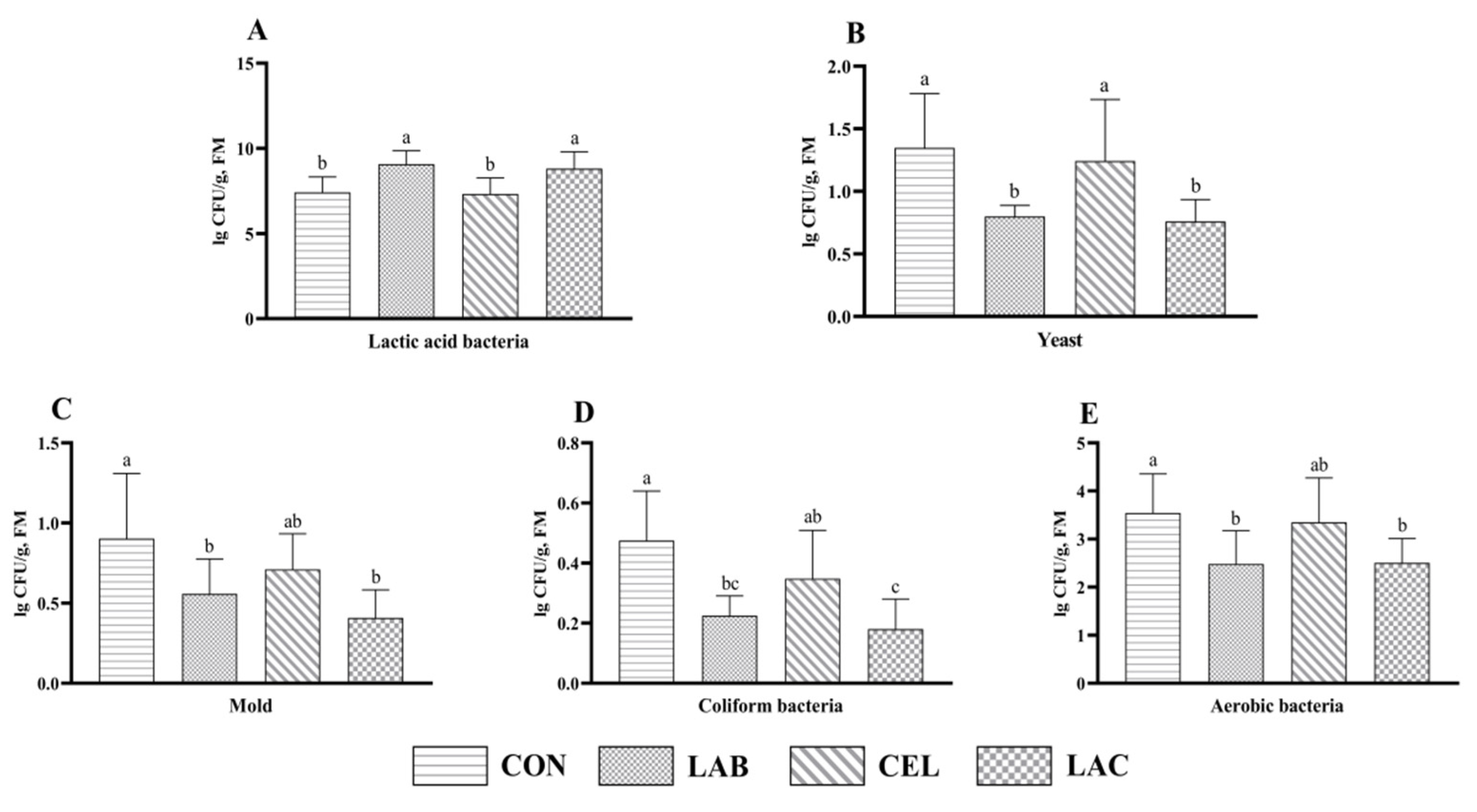

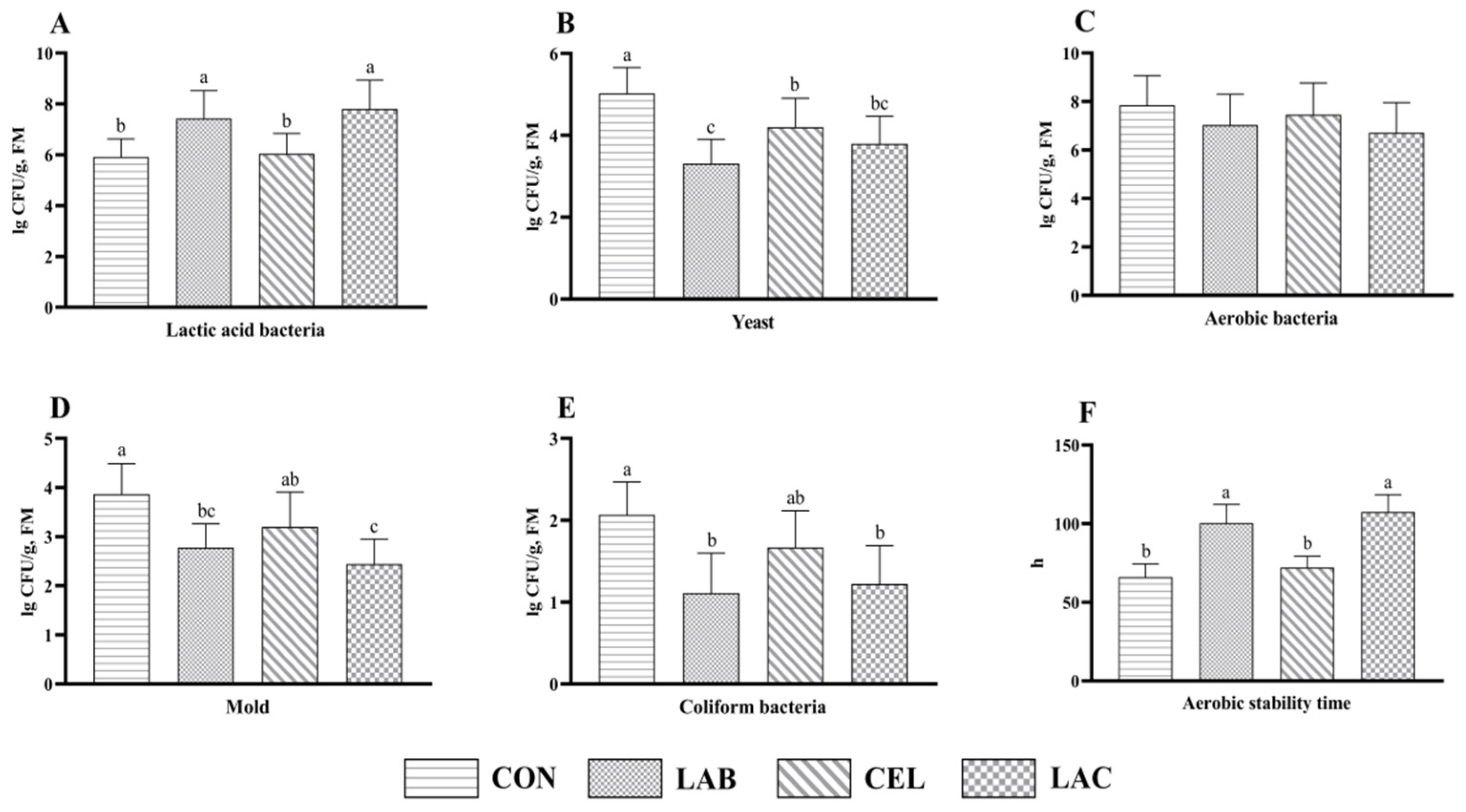

3.3. Microbial Count of Mixed Silage Composed of Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw

3.4. Aerobic Stability of Mixed Silage Composed of Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw

3.5. In Vitro Digestibility of Mixed Silage Composed of Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw

3.6. In Vitro Gas Production of Mixed Silage Composed of Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw

3.7. Gas Production Parameters of Mixed Silage Composed of Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw

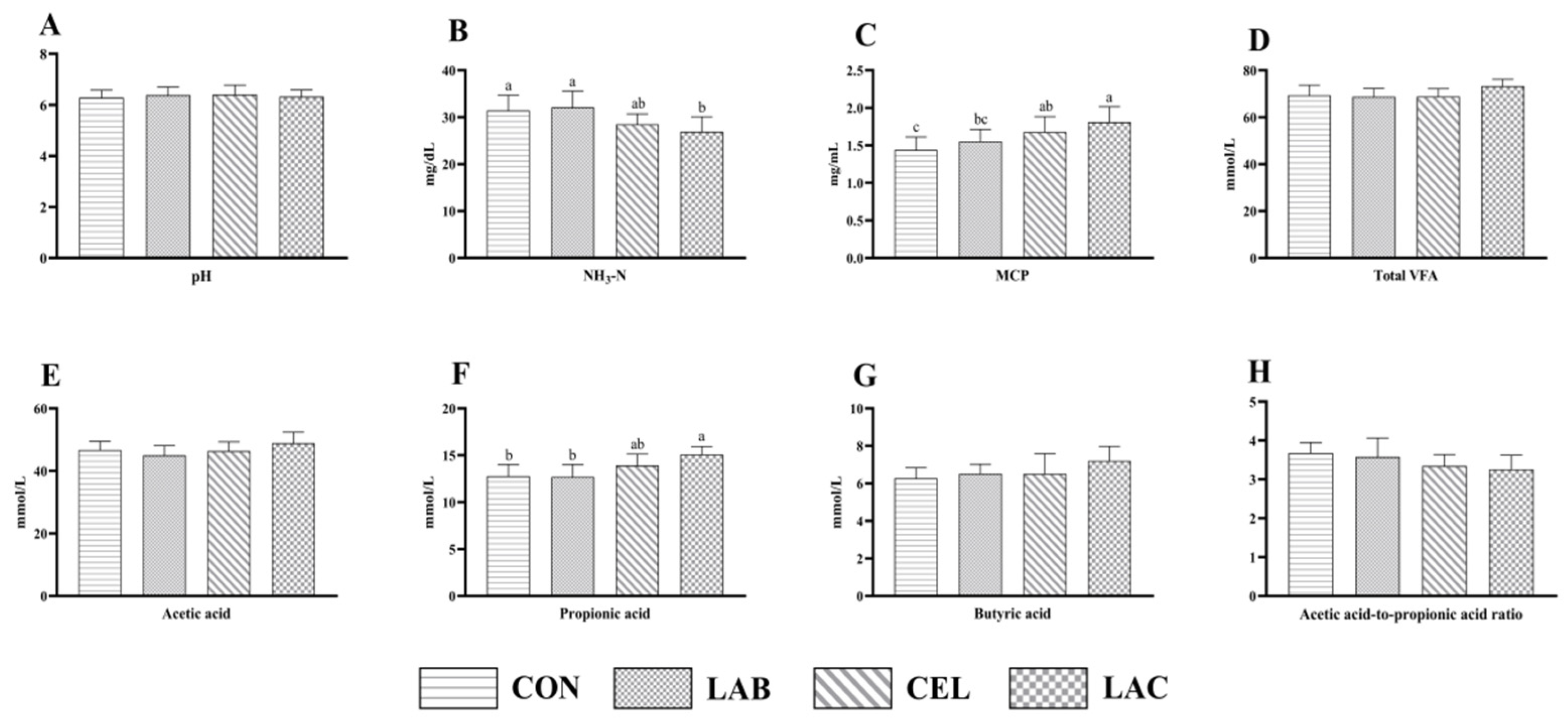

3.8. In Vitro Rumen Fermentation of Mixed Silage Composed of Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Additives on Chemical Composition of Mixed Silage

4.2. Effects of Additives on Fermentation Parameters of Mixed Silage

4.3. Effects of Additives on Microbial Count of Mixed Silage

4.4. Effects of Additives on Aerobic Stability of Mixed Silage

4.5. Effects of Additives on In Vitro Digestibility of Mixed Silage

4.6. Effects of Additives on In Vitro Gas Production of Mixed Silage

4.7. Effects of Additives on In Vitro Rumen Fermentation of Mixed Silage

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Cao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Mao, J.; Shi, H.; Shi, R.; Sun, X.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Effects of different forage types on rumen fermentation, microflora, and production performance in peak-lactation dairy cows. Fermentation 2022, 8, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, D.; Ge, Q.; Yang, B.; Li, S. Effects of harvest period and mixed ratio on the characteristic and quality of mixed silage of alfalfa and maize. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2023, 306, 115796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Rouzbehan, Y.; Rezaei, J.; Jacobsen, S.E. The effect of lactic acid bacteria inoculation, molasses, or wilting on the fermentation quality and nutritive value of amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriaus) silage. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 3983–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, F.; Xu, C.; Cai, Y. Comparative analysis of ensiling characteristics and protein degradation of alfalfa silage prepared with corn or sweet sorghum in semiarid region of Inner Mongolia. Anim. Sci. J. 2020, 91, 13321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, M.; Rouzbhan, Y.; Rezaei, J. Influence of diets containing different levels of Salicornia bigelovii forage on digestibility, ruminal and blood variables and antioxidant capacity of Shall male sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021, 281, 115085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Fan, X.; Sun, G.; Yin, F.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, Z.; Gan, S. Replacing alfalfa hay with amaranth hay: Effects on production performance, rumen fermentation, nutrient digestibility and antioxidant ability in dairy cow. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, K.; Zhou, Y.; Menhas, S.; Bundschuh, J.; Hayat, S.; Ullah, A.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P. Pennisetum giganteum: An emerging salt accumulating/tolerant non-conventional crop for sustainable saline agriculture and simultaneous phytoremediation. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 114876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xiang, C.; Xu, L.; Cui, J.; Fu, S.; Chen, B.; Yang, S.; Wang, P.; Xie, Y.; Wei, M.; et al. SMRT sequencing of a full-length transcriptome reveals transcript variants involved in C18 unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis and metabolism pathways at chilling temperature in Pennisetum giganteum. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Mao, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Yu, X.; Yang, J.; Li, R. Effects of different cutting heights on the quality of hay and silage of Pennisetum giganteum. Feed Res. 2016, 5, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, C. Comparative analysis of nutritional components of Pennisetum giganteum at different growth heights in hill regions of central Sichuan. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 33, 5313–5323. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhao, H.; He, X.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, F.; Liu, B.; Liu, Q. Effects of fermented feed of Pennisetum giganteum on growth performance, oxidative stress, immunity and gastrointestinal microflora of Boer goats under thermal stress. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1030262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Meng, Q.; Yang, J.; Xie, X. Effects of replacing the corn silage with Pennisetum giganteum silage on production performance, composition of milk and economic benefits in dairy cows. China Anim. Husb. Vet. Med. 2017, 44, 1997–2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Bao, J.; Zhuo, X.; Li, Y.; Zhan, W.; Xie, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yu, Z. Effects of Lentilactobacillus buchneri and chemical additives on fermentation profile, chemical composition, and nutrient digestibility of high-moisture corn silage. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1296392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Feng, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Fu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Peng, Z. Effects of different simulated seasonal temperatures on the fermentation characteristics and microbial community diversities of the maize straw and cabbage waste co-ensiling system. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 708, 135113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Zhou, P.; Yue, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qin, G.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Z.; Cai, Y. Fermentation characteristics, chemical composition, and aerobic stability in whole crop corn silage treated with lactic acid bacteria or Artemisia argyi. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Liu, N.; Diao, X.; He, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, W. Effects of cellulase and xylanase on fermentation characteristics, chemical composition and bacterial community of the mixed silage of king grass and rice straw. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Qin, J.; Luo, Q.; Xu, Y.; Xie, S.; Chen, R.; Wang, X.; Lu, Q. Differences in chemical composition, polyphenol compounds, antioxidant activity, and in vitro rumen fermentation among sorghum stalks. Animals 2024, 14, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Association of Official Analytical Chemists Official Methods of Analysis; AOAC: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R.P. A method for the extraction of plant samples and the determination of total soluble carbohydrates. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1958, 9, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, G.A.; Kang, J.H. Automated simultaneous determination of ammonia and total amino acids in ruminal fluid and in vitro media. J. Dairy Sci. 1980, 63, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Dong, Z.; Li, J.; Nazar, M.; Shao, T. Assessment of inoculating various epiphytic microbiota on fermentative profile and microbial community dynamics in sterile Italian ryegrass. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Na, N.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Wu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Yin, G.; Liu, S.; Liu, Z.; et al. Impact of packing density on the bacterial community, fermentation, and in vitro digestibility of whole-crop barley silage. Agriculture 2021, 11, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Lin, B.; Zou, C. Effects of sugarcane variety and nitrogen application level on the quality and aerobic stability of sugarcane tops silage. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1148884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menke, K.H.; Steingass, H. Estimation of the energetic feed value obtained from chemical analysis and in vitro gas production using rumen fluid. Anim. Res. Dev. 1988, 28, 7–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kaewpila, C.; Khota, W.; Gunun, P.; Kesorn, P.; Cherdthong, A. Strategic addition of different additives to improve silage fermentation, aerobic stability and in vitro digestibility of napier grasses at late maturity stage. Agriculture 2020, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S.; Sharma, O.P.; Dawra, R.K.; Negi, S.S. Simple determination of microbial protein in rumen liquor. J. Dairy Sci. 1982, 65, 2170–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øskov, E.R.; McDonald, I. The estimation of protein degradability in the rumen from incubation measurements weighed according to rate of passage. J. Agric. Sci. 1979, 92, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Huang, R.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W. Chemical characteristics, antioxidant capacity, bacterial community, and metabolite composition of mulberry silage ensiling with lactic acid bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1363256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y. Lactobacillus plantarum inoculants delay spoilage of high moisture alfalfa silages by regulating bacterial community composition. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Guerra, N.A.; Gonzalez-Ronquillo, M.; Anderson, R.C.; Hume, M.E.; Ruiz-Albarrán, M.; Bautista-Martínez, Y.; Zúñiga-Serrano, A.; Nájera-Pedraza, O.G.; Salinas-Chavira, J. Improvements in fermentation and nutritive quality of elephant grass [Cenchrus purpureus (Schumach.) Morrone] silages: A review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2024, 56, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Sun, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhen, Y.; Qin, G.; Wang, T.; Demelash, N.; Zhang, X. Effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum inoculation on the quality and bacterial community of whole-crop corn silage at different harvest stages. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Li, P.; Xiao, B.; Yang, F.; Li, D.; Ge, G.; Jia, Y.; Bai, S. Effects of LAB inoculant and cellulase on the fermentation quality and chemical composition of forage soybean silage prepared with corn stover. Grassl. Sci. 2020, 67, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; He, J.; Yang, X.; Xie, X. Fermentation characteristics and microbial community composition of wet brewer’s grains and corn stover mixed silage prepared with cellulase and lactic acid bacteria supplementation. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, C.; Dong, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X. Effects of cellulase and Lactobacillus plantarum on fermentation quality, chemical composition, and microbial community of mixed silage of whole-plant corn and peanut vines. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 2465–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, F.; Rodríguez, M.L.; Martínez-Fernández, A.; Soldado, A.; Argamentería, A.; Peláez, M.; Roza-Delgado, B. Subclinical ketosis on dairy cows in transition period in farms with contrasting butyric acid contents in silages. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 279614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundharrajan, I.; Park, H.S.; Rengasamy, S.; Sivanesan, R.; Choi, K.C. Application and future prospective of lactic acid bacteria as natural additives for silage production—A review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, O.C.M.; Ogunade, I.M.; Weinberg, Z.; Adesogan, A.T. Silage review: Foodborne pathogens in silage and their mitigation by silage additives. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4132–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yu, Z. Effects of mixing red clover with alfalfa at different ratios on dynamics of proteolysis and protease activities during ensiling. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 8954–8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Yun, Y.; Yu, Z. Propionic acid and sodium benzoate affected biogenic amine formation, microbial community, and quality of oat silage. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 750920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Huang, P.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Q. Novel strategy to understand the aerobic deterioration of corn silage and the influence of Neolamarckia cadamba essential oil by multi-omics analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 148715. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura, F.; Sugiura, T.; Munby, M.; Shiokura, Y.; Murata, R.; Nakamura, T.; Fujiki, J.; Iwano, H. Relationship between Escherichia coli virulence factors, notably kpsMTII, and symptoms of clinical metritis and endometritis in dairy cows. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 84, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wang, P.; Li, F.; Du, J.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, T.; Yi, Q.; Tang, H.; Yuan, B. Fermentation quality and in vitro digestibility of sweet corn processing byproducts silage mixed with millet hull or wheat bran and inoculated with a lactic acid bacteria. Fermentation 2024, 10, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Yu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Shao, T.; Na, R.; Zhao, M. Effects of lactic acid bacteria inoculants and cellulase on fermentation quality and in vitro digestibility of Leymus chinensis silage. Grassl. Sci. 2014, 60, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Tahir, M.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Teng, K.; Fu, Z.; Yun, F.; Wang, S.; et al. Lactobacillus cocktail and cellulase synergistically improve the fiber transformation rate in Sesbania cannabina and sweet sorghum mixed silage. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yuan, X.J.; Li, J.F.; Dong, Z.H.; Wang, S.R.; Guo, G.; Shao, T. Effects of applying lactic acid bacteria and propionic acid on fermentation quality, aerobic stability and in vitro gas production of forage-based total mixed ration silage in Tibet. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2019, 59, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Xu, J.; Guo, L.; Chen, F.; Jiang, D.; Lin, Y.; Guo, C.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Ni, K.; et al. Exploring the effects of different bacteria additives on fermentation quality, microbial community and in vitro gas production of forage oat silage. Animals 2022, 12, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maake, T.W.; Aiyegoro, O.A.; Adeleke, M.A. Effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Enterococcus faecalis supplementation as direct-fed microbials on rumen microbiota of boer and speckled goat breeds. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Cao, G.; Hu, R.; Wang, X.; Zou, H.; Kang, K.; Peng, Q.; Xue, B.; et al. Active dry yeast supplementation improves the growth performance, rumen fermentation, and immune response of weaned beef calves. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 1352–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Y.; Qin, S.L.; Zheng, Y.N.; Geng, H.J.; Chen, L.; Yao, J.H.; Deng, L. Propionate promotes gluconeogenesis by regulating mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway in calf hepatocytes. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 15, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, M.; Dong, C.; Zhang, R.; Du, L.; Zheng, Y.; Wei, M.; Wei, M.; Wu, B. Effects of cellulase and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on the fermentation quality, microbial diversity, gene function prediction, and in vitro rumen fermentation parameters of Caragana korshinskii silage. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 2, 1108043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | OM | DM | NDF | ADF | CP | WSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pennisetum giganteum | 88.17 | 15.13 | 56.97 | 36.85 | 13.28 | 6.76 |

| Rice straw | 87.75 | 89.67 | 71.05 | 46.72 | 5.17 | 2.42 |

| Ingredients | Nutrient Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | 32.97 | CP (%) | 13.60 |

| Cottonseed meal | 3.88 | NDF (%) | 37.42 |

| Wheat bran | 6.08 | ADF (%) | 22.06 |

| Corn gluten meal | 5.16 | Ca (%) | 0.76 |

| Soybean meal | 3.12 | P (%) | 0.41 |

| NaCl | 0.50 | ME 2 (MJ/kg) | 8.67 |

| Limestone | 1.09 | ||

| Premix 1 | 2.20 | ||

| Alfalfa hay | 10.05 | ||

| Corn straw | 34.95 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | LAB | CEL | LAC | |||

| DM | 22.76 b | 26.31 a | 23.27 b | 27.49 a | 0.719 | 0.039 |

| NDF | 59.38 a | 57.72 ab | 53.62 ab | 52.32 b | 1.059 | 0.046 |

| ADF | 39.31 a | 38.04 ab | 35.27 bc | 34.10 c | 0.732 | 0.031 |

| OM | 86.65 | 85.24 | 89.04 | 88.27 | 0.626 | 0.133 |

| CP | 7.02 b | 7.13 b | 7.55 ab | 8.03 a | 0.124 | 0.006 |

| WSC | 2.77 | 2.28 | 2.67 | 2.36 | 0.117 | 0.396 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | LAB | CEL | LAC | |||

| pH | 4.10 a | 3.76 b | 3.80 b | 3.66 b | 0.055 | 0.020 |

| Lactic acid (%, DM) | 4.67 c | 5.74 ab | 5.03 bc | 6.37 a | 0.198 | 0.004 |

| Acetic acid (%, DM) | 1.45 a | 1.22 ab | 1.17 b | 1.02 b | 0.050 | 0.013 |

| Propionic acid (%, DM) | 0.042 a | 0.022 b | 0.019 b | 0.009 c | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Butyric acid (%, DM) | 0.004 | ND | 0.001 | ND | 0.001 | 0.075 |

| Lactic acid/Acetic acid | 3.25 c | 4.78 b | 4.38 bc | 6.48 a | 0.328 | 0.001 |

| NH3-N/total nitrogen | 5.47 a | 4.25 b | 4.16 b | 3.76 b | 0.219 | 0.022 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | LAB | CEL | LAC | |||

| IVDMD | 48.82 | 53.12 | 50.14 | 54.02 | 0.840 | 0.084 |

| IVOMD | 54.71 | 52.29 | 51.48 | 54.09 | 1.472 | 0.870 |

| IVCPD | 54.95 b | 53.49 b | 57.31 ab | 60.23 a | 0.941 | 0.048 |

| IVNDFD | 34.31 b | 32.99 b | 39.38 a | 38.64 a | 0.791 | 0.002 |

| IVADFD | 28.16 | 29.22 | 32.52 | 31.67 | 0.711 | 0.092 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | LAB | CEL | LAC | |||

| 2 h | 14.22 b | 16.25 ab | 14.90 ab | 16.88 a | 0.388 | 0.047 |

| 4 h | 18.18 b | 21.96 a | 17.69 b | 21.87 a | 0.702 | 0.031 |

| 8 h | 26.24 b | 31.71 a | 27.26 b | 32.04 a | 0.843 | 0.013 |

| 12 h | 33.32 b | 38.96 ab | 35.03 ab | 40.63 a | 1.062 | 0.041 |

| 24 h | 48.38 b | 56.54 a | 51.21 ab | 55.78 a | 1.141 | 0.022 |

| 48 h | 68.09 | 74.37 | 72.64 | 76.17 | 1.301 | 0.085 |

| 72 h | 73.97 | 76.87 | 75.31 | 80.69 | 1.445 | 0.407 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | LAB | CEL | LAC | |||

| A (mL/g) | 1.26 | 1.50 | 1.25 | 1.67 | 0.069 | 0.088 |

| B (mL/g) | 68.28 b | 72.68 ab | 73.93 a | 76.47 a | 1.047 | 0.032 |

| A + B (mL/g) | 69.54 b | 74.18 ab | 75.18 ab | 78.13 a | 1.080 | 0.030 |

| C (%/h) | 0.075 | 0.067 | 0.062 | 0.060 | 0.004 | 0.596 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, J.; Lin, L.; Lu, Y.; Weng, B.; Feng, Y.; Du, C.; Wei, C.; Gao, R.; Gan, S. The Influence of Silage Additives Supplementation on Chemical Composition, Aerobic Stability, and In Vitro Digestibility in Silage Mixed with Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14111953

Ma J, Lin L, Lu Y, Weng B, Feng Y, Du C, Wei C, Gao R, Gan S. The Influence of Silage Additives Supplementation on Chemical Composition, Aerobic Stability, and In Vitro Digestibility in Silage Mixed with Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw. Agriculture. 2024; 14(11):1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14111953

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Jian, Lu Lin, Yuezhang Lu, Beiyu Weng, Yaochang Feng, Chunmei Du, Chen Wei, Rui Gao, and Shangquan Gan. 2024. "The Influence of Silage Additives Supplementation on Chemical Composition, Aerobic Stability, and In Vitro Digestibility in Silage Mixed with Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw" Agriculture 14, no. 11: 1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14111953

APA StyleMa, J., Lin, L., Lu, Y., Weng, B., Feng, Y., Du, C., Wei, C., Gao, R., & Gan, S. (2024). The Influence of Silage Additives Supplementation on Chemical Composition, Aerobic Stability, and In Vitro Digestibility in Silage Mixed with Pennisetum giganteum and Rice Straw. Agriculture, 14(11), 1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14111953