China and Countries along the “Belt and Road”: Agricultural Trade Volatility Decomposition and Food Security

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- In terms of methodology, based on the assumptions of CMS model construction, it combines the modified multi-country multi-product CMS model and the two-country multi-product CMS model to measure the trade volatility factors, which is conducive to reflecting more valuable information.

- (2)

- In terms of sample, we do not restrict to a specific agricultural product and some regions, but take all agricultural products and all B&R countries as the research objects, and categorize the agricultural products and regions to explore the trade volatility factors, which make the research sample size more comprehensive and detailed, and helps to draw more comprehensive conclusions.

- (3)

- In terms of time chain, the three important time points and the latest data on China’s accession to the WTO, the global financial crisis, and the “Belt and Road” initiative are selected as the decomposition objects, with a view to providing a basis for food security cooperation between China and the B&R countries in the context of China’s response to global emergencies.

2. Data Description, Trend Characteristics and Research Methodology

2.1. Description of Study Subjects and Data

- (1)

- Definition of the research area. Since “Belt and Road Initiative” is an open international economic cooperation region, the academic community has not yet precisely defined the distribution range, this paper refers to the definition method of Han Dong and Li Guangsi (2020) [33], and divides B&R countries into 6 regions and 60 countries: ① Mongolia Russia, including Mongolia and Russia; ② Central Asia, including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan 5 countries; ③ Southeast Asia, including Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Brunei, Philippines, Myanmar, Timor-Leste 11 countries; ④ South Asia, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Maldives 8 countries. ⑤ West Asia Middle East, including Turkey, Iran, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Yemen, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Egypt 18 countries; ⑥ Central and Eastern Europe, including Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Romania, Bulgaria Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Ukraine 16 countries.

- (2)

- The scoping of agricultural products. Based on the WTO Agreement on Trade in Agricultural Products, chapters 1–24 of the International Convention on the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS) are defined as agricultural products, and with reference to the method of Yusheng Chen et al. (2022) [34], agricultural products 1–5, 6–15, and 16–24 are classified as animal, fruit and vegetable, and food processing products, respectively. To ensure data consistency, the HS1996 commodity classification approach was used in this paper, and the data were obtained from the UN COMTRADE database. The specific database links are as follows: Download trade data | UN Comtrade: International Trade Statistics.

2.2. Trends in Agricultural Trade between China and B&R Countries

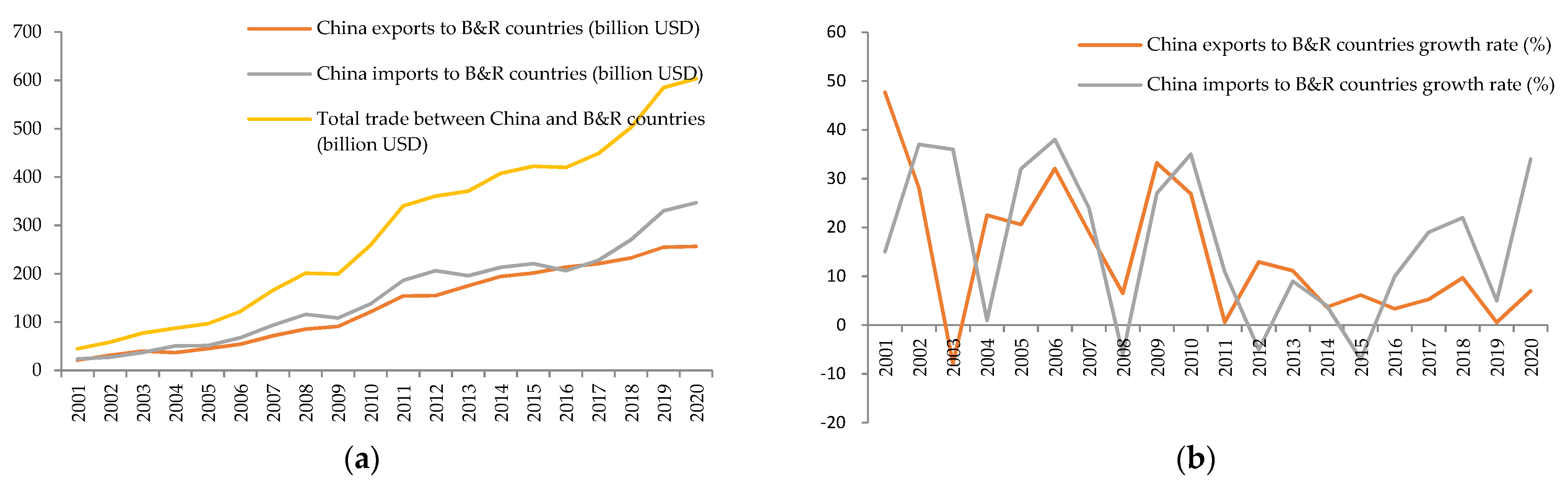

2.2.1. Trade Scale Trend

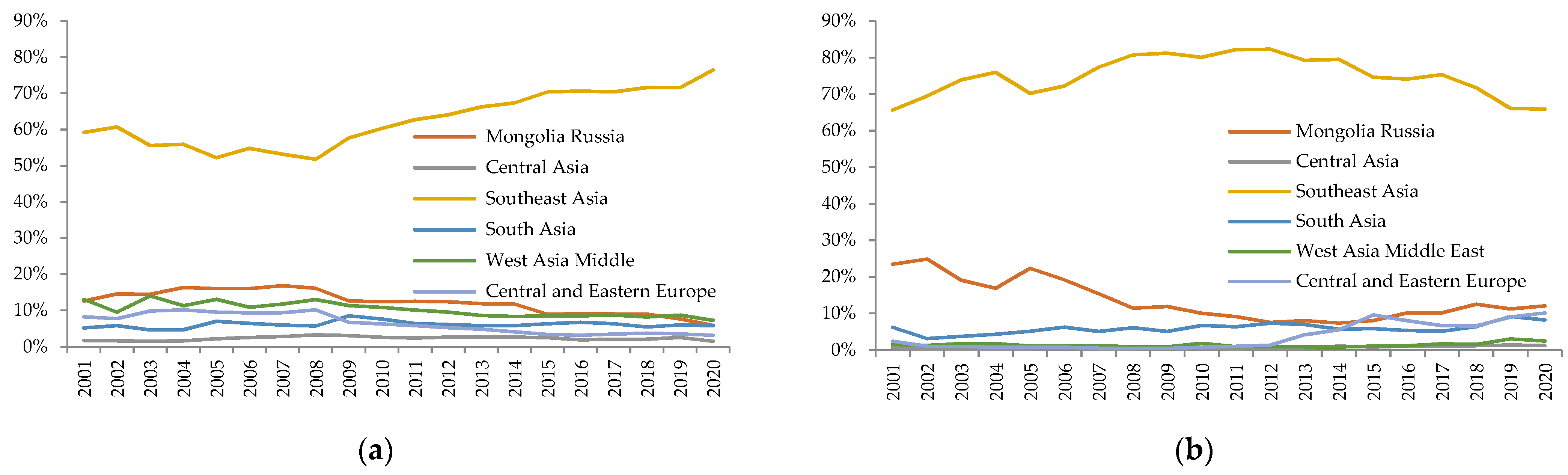

2.2.2. Market Distribution Trend

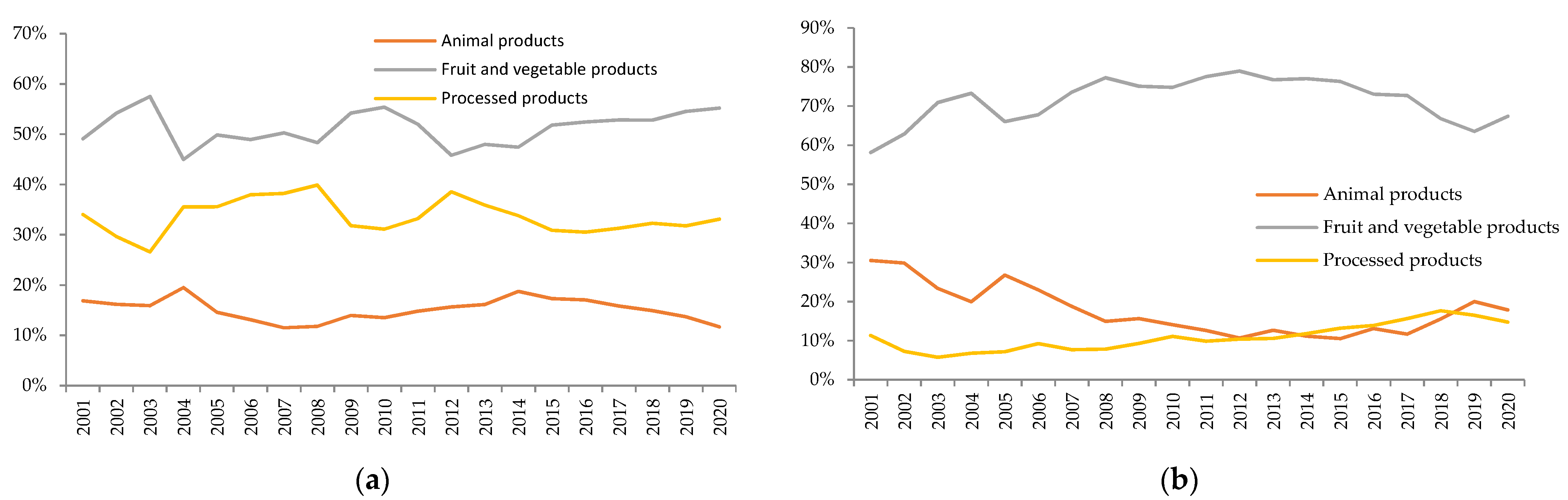

2.2.3. Trends in the Distribution of Agricultural Products Types

2.3. Research Methodology

2.3.1. Modified Multi-Country, Multi-Product CMS Model

2.3.2. CMS Model of Multi-Product in Two Countries

3. Results

3.1. Holistic Analysis

3.1.1. Empirical Results of China’s Agricultural Exports to B&R Countries

3.1.2. Empirical Results of B&R Countries Export Agricultural to China

3.2. Regional Distribution Analysis

3.2.1. Empirical Results of China’s Exports Agricultural to Regions along B&R Countries

3.2.2. Empirical Results of Regions along B&R Countries Export Agricultural to China

3.3. Product Type Distribution Analysis

3.3.1. Empirical Results on the Types of China Exports Agricultural to B&R Countries

3.3.2. Empirical Results on the Types of B&R Countries Export Agricultural to China

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of the Results of This Paper with the Existing Literature

- (1)

- In terms of methodology, combining the modified multi-country multi-product CMS model with the two-country multi-product CMS model to measure trade volatility factors can maximize the useful information on market structure effects and factor decomposition of import trade influences, e.g., Cao and Tong (2018), Feng and Li (2022) both used a multi-country multi-product CMS model to analyze United States exports and Chinese exports of agricultural products from the RCEP region, but did not analyze the factor decomposition of import trade fluctuations and did not further analyze the factors affecting import trade by combining the principle of bilateral equivalence of import and export trade [14,15]. Liu and Xiao (2018), Yao and Xu (2021) used a two-country multi-product CMS model to analyze the factors of import and export trade volatility between China and Central and Eastern European countries, but Central and Eastern European countries are composed of 16 countries and trade growth is influenced by market effects, but using a two-country multi-product CMS model assumes 16 countries as one country, and the conclusions drawn from the study ignore the market effects. Therefore, according to the actual situation of import and export, the combination of the two analysis methods can yield more valuable information [16,17].

- (2)

- In terms of the sample of agricultural products, it is not limited to a specific agricultural product, but takes all agricultural products as the research object, and categorizes agricultural products to explore the trade volatility factors, which makes the research sample size more comprehensive and detailed and is conducive to more comprehensive conclusions. For example, aquatic products, cereals, grains, pork, apples, and corn, respectively [9,17,18,19,20,21,22], but the sample size of the study is not broad enough to reflect the overall agricultural trade fluctuation factors, although China’s exports to BRICS countries, Japan, Latin American countries, ASEAN, RCEP, and United States trade fluctuations with overall agricultural products samples, respectively [23,24,25,26,27,28,29], and the sample size of the study area is narrow, which cannot reflect China’s cooperation with B&R countries as a whole the situation.

- (3)

- In terms of regional samples, it is not limited to some regions, but takes all B&R countries as the research objects, and explores the trade volatility factors among different regions based on the overall sample and classified by regions. The existing literature, which does not classify the overall agricultural products, is again decomposed to explore the factors of specific agricultural trade fluctuations. Yang and Huang (2019), Yao and Xu (2021), Guo and Xiao (2021) explored the overall agricultural trade volatility of Vietnam, Eastern European countries, and SCO members [16,30,31], but took some representatives of B&R countries as examples. However, the trade fluctuation factors of different regions were not analyzed in a disaggregated manner with all countries as the sample.

4.2. Food Security Cooperation between China and B&R Countries

4.3. Research Shortcomings and Possible Future Research Directions of This Paper

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, C.X.; Gao, M.; Han, L. A study on the impact of supply-side import-side changes on China’s food security. China Rural Econ. 2021, 1, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Daumantas, B. Salmon price volatility: A weight-class-specific multivariate approach. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2016, 20, 24–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Du, W.T. Price fluctuations of fish resources trade between China and ASEAN: An example of frozen mackerel export prices. J. Natural Res. 2020, 35, 2191–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, R.H.; Madan, M.D.; Carole, R.E. Forecasting monthly catfish pond bank and feed prices. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2019, 23, 86–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo, F.P.; Pilar, G.R. Asymmetric Price Volatility Transmission in the Spanish Fresh Wild Fish Supply Chain. Marine Res. Econ. 2020, 35, 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, M.H.; Wang, F.; Feng, Q.R. Research on the impact of international wood forest products price fluctuations on the volume of China’s wood forest products import and export trade. J. Agric. Fore. Econ. Manag. 2022, 21, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.D.; Li, C.X. Study on the spillover effects of trade fluctuations of Chinese dairy imports. Agric. Econ. Issues 2022, 07, 64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ewald, C.O.; Haugom, E.; Kanthan, L.; Lien, G.; Salehi, P.; Størdal, S. Salmon futures and the Fish Pool market in the context of the CAPM and a three-factor model. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2022, 26, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.L.; Li, X.D. Trade size, trade structure, trade competitiveness and changes in China’s grain trade-an empirical analysis based on a modified CMS model. Int. Econ. Trade Explor. 2015, 31, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.J.; Ding, X.Q. Growth patterns of inter-provincial transfer out in China: Drivers, multi-layer decomposition and competitiveness dissection. Quantitative Econ. Tech. Econ. Res. 2020, 37, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Tyszynski, H. World Trade in Manufactured Commodities, 1899–19501. Manch. School 1951, 19, 272–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepma, C.J. Extensions and Application Possibilities of the Constant Market Shares Analysis. The Case of the Developing Countries’ Export. Doctoral Dissertation, University Groningen, Groningue, The Netherlands, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Milana, C. Constant-market-shares analysis and index number theory. Eur. J. Political Econ. 1988, 4, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.P.; Tong, J.X. Dynamic decomposition of the causes of United States agricultural export volatility. J.S. China Agric. Univ. 2018, 17, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.X.; Li, C. Analysis of China’s competitive advantages and drivers of agricultural exports in the context of RCEP. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2022, 42, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.P.; Xiao, H.F. Research on the causes of growth of agricultural trade between China and 16 Central and Eastern European countries—An empirical analysis based on CMS model. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2018, 9, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, C.M.; Xu, X.K.; Wang, Y. Dynamic decomposition of the causes of agricultural trade growth between China and Eastern European countries. Stat. Deci. 2021, 37, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Lin, L. Analysis of growth factors of bilateral trade of aquatic products between China and ASEAN. Bus. Res. 2014, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.H.; Zhang, J.B.; Yang, C.X.; Lu, Z.H.; Chen, X.J. Analysis of factors influencing trade fluctuations of Chinese cephalopod exports. Marine Lake Marsh Bull. 2021, 43, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Mu, Y.Y. A study on the decomposition of China-Australia grain trade and its influencing factors based on CMS model. Inter. Econ. Trade Explor. 2015, 31, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.X.; Wang, K.; Gao, F. Research on the influencing factors of China’s pork export volatility. Stat. Deci. 2015, 21, 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Gao, D.; Bao, L.M. Analysis of the reasons for the decline of international competitiveness of China’s apple products. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2017, 9, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.P.; Liu, S. Study on W-shaped fluctuations and trade effects of China’s corn import and export. Econ. Vertical 2021, 7, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P. Research on dynamic fluctuation of China’s export trade growth to BRICS countries—Factor decomposition and measurement based on CMS model. Inter. Trade Issues 2015, 5, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.M.; Zong, Y.X. Analysis of factors influencing China’s agricultural export trade to other BRICS countries. Stat. Deci. 2019, 35, 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Zheng, X.D. Research on the characteristics and causes of the growth of China-Japan agricultural trade. J. Hunan Univ. 2016, 30, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.P. Analysis of the causes of agricultural trade fluctuations between China and Latin American countries. J. S. China Agric. Univ. 2017, 16, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Hou, C.L.; Song, Y. A study on the factors influencing China’s agricultural exports to ASEAN. Inter. Trade Issues 2017, 11, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, M.; Gao, Y.D. Study on the fluctuation factors of China’s agricultural exports to RCEP. Stat. Inf. Forum 2021, 36, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.Y.; Li, D.H. Analysis of the causes of tea export trade volatility in China to the United States market—Based on the modified CMS model. Tea Sci. 2021, 41, 876–888. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Huang, Z.M. Study on the factors influencing the growth of China-Vietnam agricultural trade under the “Belt and Road” initiative: An analysis based on the modified CMS model. World Agric. 2019, 8, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.J.; Xiao, H.F. Analysis of factors influencing the fluctuation of agricultural trade between China and SCO member states in the context of “Belt and Road”. J. Xinjiang Univ. 2021, 49, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; Li, G.S. Evolution of food trade patterns and influence mechanisms between China and countries along the “Belt and Road”-based on social network science perspective. Agric. Econ. Issues 2020, 8, 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S. Effects of Chinese agricultural exports and trade prospects in RCEP FTA: An empirical analysis based on stochastic model and market segmentation. China Circ. Econ. 2022, 36, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

| Influencing Factor | 2001–2007 | 2008–2009 | 2010–2013 | 2014–2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | |

| Change in export volume | 5.07 | 100.00 | 0.56 | 100.00 | 5.36 | 100.00 | 6.23 | 100.00 |

| 1. Demand effect DE1 | 2.46 | 48.48 | −0.92 | −165.53 | 4.08 | 76.12 | −0.57 | −9.20 |

| 2. Structure effort SE1 | −0.04 | −0.78 | 0.16 | 29.02 | −0.06 | −1.14 | 2.11 | 33.84 |

| Market structure effort MSE1 | −0.06 | −1.11 | −0.01 | −2.16 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 1.24 | 19.95 |

| Product structure effort PSE1 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 31.18 | −0.08 | −1.48 | 0.87 | 13.89 |

| 3. Competitive effort CE1 | 2.65 | 52.37 | 1.30 | 232.49 | 1.33 | 24.77 | 4.70 | 75.41 |

| Market competitive effort MCE1 | 1.37 | 26.94 | 0.73 | 130.91 | 0.61 | 11.35 | 2.16 | 34.71 |

| Product competitive effort PCE1 | 1.29 | 25.43 | 0.57 | 101.58 | 0.72 | 13.42 | 2.53 | 40.70 |

| Influencing Factor | 2001–2007 | 2008–2009 | 2010–2013 | 2014–2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | |

| Change in export volume | 6.98 | 100.00 | −0.72 | 100.00 | 5.82 | 100.00 | 13.37 | 100.00 |

| 1. Demand efforts DE2 | 7.78 | 111.41 | −1.01 | 138.91 | 6.72 | 115.51 | 9.70 | 72.55 |

| Scale demand effect SDE2 | 5.63 | 80.66 | −1.15 | 158.34 | 12.38 | 212.93 | 14.10 | 105.48 |

| Product demand effect PDE2 | 2.15 | 30.76 | 0.14 | −19.43 | −5.67 | −97.42 | −4.40 | −32.93 |

| 2. Competitive effort CE2 | 0.08 | 1.16 | 0.37 | −50.67 | −0.72 | −12.39 | 2.05 | 15.33 |

| Scale competitiveness effect SCE2 | 0.40 | 5.73 | 0.24 | −32.86 | −1.94 | −33.30 | 2.08 | 15.58 |

| Product competitiveness effect PCE2 | −0.32 | −4.57 | 0.13 | −17.81 | 1.22 | 20.91 | −0.03 | −0.25 |

| 3. Second-order efforts SE2 | −0.88 | −12.58 | −0.09 | 11.78 | −0.18 | −3.12 | 1.62 | 12.12 |

| Second-order effect of scale SSE2 | −1.71 | −24.42 | 0.01 | −1.12 | −0.12 | −1.97 | 0.37 | 2.74 |

| Product second-order effect PSE2 | 0.83 | 11.85 | −0.09 | 12.89 | −0.07 | −1.15 | 1.26 | 9.39 |

| Region | Influencing Factor | 2001–2013 | 2014–2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | ||

| Mongolia Russia | Change in export volume | 1.81 | 100.00 | −0.78 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE1 | 1.05 | 58.24 | −0.62 | 78.87 | |

| Structure effort SE1 | 0.22 | 12.34 | 0.04 | −5.11 | |

| Competitive effort CE1 | 0.53 | 29.42 | −0.21 | 26.23 | |

| Central Asia | Change in export volume | 0.42 | 100.00 | −0.14 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE1 | 0.21 | 50.40 | 0.16 | −118.80 | |

| Structure effort SE1 | 0.12 | 28.45 | −0.16 | 115.64 | |

| Competitive effort CE1 | 0.09 | 21.16 | −0.14 | 103.16 | |

| Southeast Asia | Change in export volume | 10.34 | 100.00 | 6.54 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE1 | 3.95 | 38.17 | 2.75 | 42.08 | |

| Structure effort SE1 | 0.17 | 1.66 | 1.53 | 23.34 | |

| Competitive effort CE1 | 6.22 | 60.17 | 2.26 | 34.58 | |

| South Asia | Change in export volume | 0.91 | 100.00 | 0.35 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE1 | 0.23 | 25.20 | −0.23 | −66.22 | |

| Structure effort SE1 | 0.02 | 1.99 | 0.91 | 256.81 | |

| Competitive effort CE1 | 0.66 | 72.81 | −0.32 | −90.63 | |

| West Asia Middle | Change in export volume | 1.23 | 100.00 | 0.24 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE1 | 0.75 | 60.62 | −0.43 | −179.51 | |

| Structure effort SE1 | 0.02 | 1.52 | 0.34 | 144.68 | |

| Competitive effort CE1 | 0.47 | 37.86 | 0.32 | 134.83 | |

| Central and Eastern Europe | Change in export volume | 0.67 | 100.00 | 0.01 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE1 | 0.64 | 95.68 | 0.18 | 1492.2 | |

| Structure effort SE1 | 0.13 | 19.41 | 0.01 | 76.02 | |

| Competitive effort CE1 | −0.10 | −15.1 | −0.17 | −1468.22 | |

| Region | Influencing Factor | 2001–2013 | 2014–2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | ||

| Mongolia Russia | Change in export volume | 1.02 | 100.00 | 2.61 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE2 | 2.13 | 208.27 | 0.98 | 37.50 | |

| Competitive effort CE2 | −0.22 | −21.49 | 1.16 | 44.29 | |

| Second-order efforts SE2 | −0.89 | −86.77 | 0.48 | 18.21 | |

| Central Asia | Change in export volume | 0.11 | 100.00 | 0.19 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE2 | 0.06 | 54.16 | 0.09 | 49.11 | |

| Competitive effort CE2 | 0.00 | −2.84 | 0.16 | 82.07 | |

| Second-order efforts SE2 | 0.05 | 48.68 | −0.06 | −31.18 | |

| Southeast Asia | Change in export volume | 13.98 | 100.00 | 5.91 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE2 | 15.27 | 109.17 | 7.41 | 125.37 | |

| Competitive effort CE2 | −0.09 | −0.65 | −1.54 | −26.05 | |

| Second-order efforts SE2 | −1.19 | −8.53 | 0.04 | 0.68 | |

| South Asia | Change in export volume | 1.22 | 100.00 | 1.63 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE2 | 0.73 | 59.85 | 0.50 | 30.42 | |

| Competitive effort CE2 | 0.03 | 2.28 | 0.57 | 34.67 | |

| Second-order efforts SE2 | 0.46 | 37.87 | 0.57 | 34.91 | |

| West Asia Middle | Change in export volume | 0.14 | 100.00 | 0.68 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE2 | 0.28 | 200.69 | 0.14 | 20.02 | |

| Competitive effort CE2 | −0.01 | −10.18 | 0.26 | 38.54 | |

| Second-order efforts SE2 | −0.13 | −90.51 | 0.28 | 41.44 | |

| Central and Eastern Europe | Change in export volume | 0.76 | 100.00 | 2.34 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE2 | 0.62 | 81.13 | 0.58 | 24.85 | |

| Competitive effort CE2 | 0.02 | 2.12 | 1.45 | 61.83 | |

| Second-order efforts SE2 | 0.13 | 16.75 | 0.31 | 13.32 | |

| Category | Influencing Factor | 2001−2013 | 2014−2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | ||

| Animal products | Change in export volume | 2.46 | 100.00 | −0.64 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE1 | 1.25 | 50.68 | −0.27 | 41.74 | |

| Structure effort SE1 | 0.07 | 2.62 | 0.39 | −60.36 | |

| Competitive effort CE1 | 1.15 | 46.70 | −0.76 | 118.62 | |

| Fruit and vegetable products | Change in export volume | 7.35 | 100.00 | 4.95 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE1 | 3.00 | 40.84 | −0.52 | −10.40 | |

| Structure effort SE1 | 0.39 | 5.27 | 1.78 | 35.91 | |

| Competitive effort CE1 | 3.96 | 53.88 | 3.69 | 74.49 | |

| Processed products | Change in export volume | 5.56 | 100.00 | 1.92 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE1 | 2.25 | 40.39 | 0.19 | 9.85 | |

| Structure effort SE1 | −0.01 | −0.20 | 0.17 | 8.81 | |

| Competitive effort CE1 | 3.33 | 59.82 | 1.56 | 81.34 | |

| Category | Influencing Factor | 2001–2013 | 2014–2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | Export Value (b. USD) | Contribution (%) | ||

| Animal products | Change in export volume | 1.76 | 100.00 | 3.82 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE2 | 2.81 | 159.85 | 1.79 | 46.86 | |

| Competitive effort CE2 | −0.20 | −11.44 | 1.19 | 31.14 | |

| Second-order efforts SE2 | −0.85 | −48.41 | 0.84 | 22.00 | |

| Fruit and vegetable products | Change in export volume | 13.67 | 100.00 | 6.96 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE2 | 14.60 | 106.79 | 5.77 | 82.90 | |

| Competitive effort CE2 | −0.05 | −0.35 | 0.45 | 6.52 | |

| Second-order efforts SE2 | −0.88 | −6.43 | 0.74 | 10.59 | |

| Processed products | Change in export volume | 1.81 | 100.00 | 2.59 | 100.00 |

| Demand efforts DE2 | 1.68 | 92.79 | 2.14 | 82.58 | |

| Competitive effort CE2 | −0.03 | −1.90 | 0.41 | 15.71 | |

| Second-order efforts SE2 | 0.17 | 9.11 | 0.04 | 1.71 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, L.; Tong, G.; Qi, J.; He, L. China and Countries along the “Belt and Road”: Agricultural Trade Volatility Decomposition and Food Security. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111850

Zhou L, Tong G, Qi J, He L. China and Countries along the “Belt and Road”: Agricultural Trade Volatility Decomposition and Food Security. Agriculture. 2022; 12(11):1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111850

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Lunzheng, Guangji Tong, Jiaguo Qi, and Lu He. 2022. "China and Countries along the “Belt and Road”: Agricultural Trade Volatility Decomposition and Food Security" Agriculture 12, no. 11: 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111850

APA StyleZhou, L., Tong, G., Qi, J., & He, L. (2022). China and Countries along the “Belt and Road”: Agricultural Trade Volatility Decomposition and Food Security. Agriculture, 12(11), 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111850