Competitiveness of the EU Agri-Food Sector on the US Market: Worth Reviving Transatlantic Trade?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Possible Economic Effects of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership for the EU and US Economies

2.2. Possible Agri-Food Effects of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership

2.3. International Competitiveness of the Agri-Food Sector in the EU Countries

3. Materials and Methods

- The Balassa Revealed Comparative Advantage Index (RCA) [57]:where: X—export, i—analyzed country, j—analyzed product/group of products, k—all goods, n—reference country/countries. Values of RCA greater than 1 denote an advantageous competitive situation, while lower values indicate a lack of comparative advantages.RCAij = RXAij = (Xij/Xik)/(Xnj/Xnk)

- The Vollrath Revealed Competitiveness Index (RC), which positive value denotes a competitive advantage, while a negative value shows a disadvantageous competitive situation [61]:where:RCij = ln (RXAij) − ln (RMAij)RMAij = (Mij/Mik)/(Mnj/Mnk)

- The Revealed Symmetric Comparative Advantage index (RSCA), which assumes values in the range of [−1, 1]. Values of RSCA lesser than zero denote a lack of comparative advantage, while greater values show such an advantage [72]:RSCAij = (RCAij − 1) (RCAij + 1)

- The Lafay Trade Balance Index (TBI) [81]:TBIij = (Xij − Mij)/(Xij + Mij)

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Commodity Structure of the Agri-Food Trade between the EU and the US

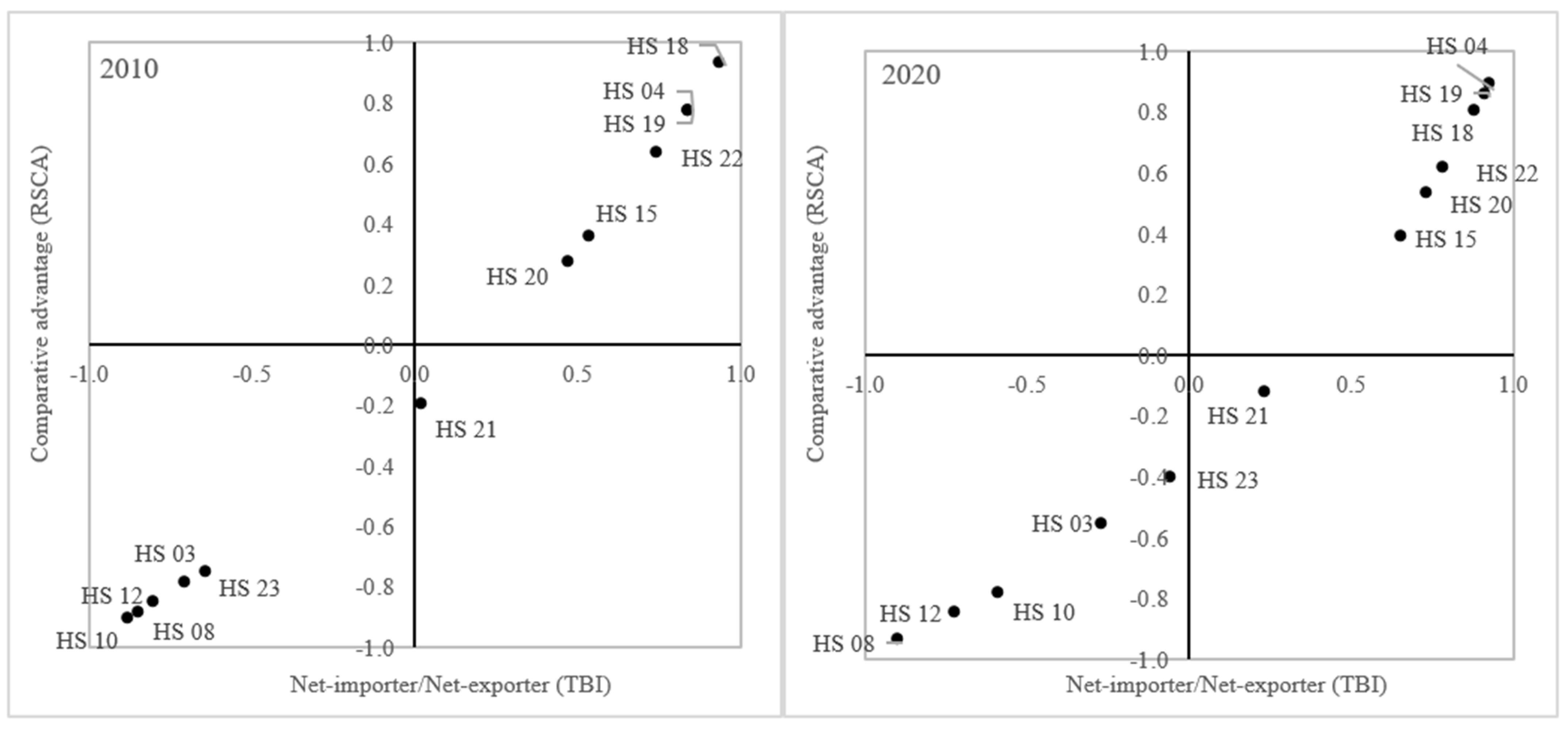

4.2. Product Mapping of the EU Agri-Food Trade with the US

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wojciechowski, H. Światowy Rynek Żywności. Powstanie—Rozwój—Przemiany (World Food Market. Rise—Development—Changes); Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warsaw, Poland, 1980. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD Data Center. Available online: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Adamowicz, M. Handel Zagraniczny a Rolnictwo (Foreign Trade and Agriculture); Książka i Wiedza: Warsaw, Poland, 1988. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bonciu, F. Transatlantic economic relations and the prospects of a new partnership. Rom. J. Eur. Aff. 2013, 13, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.I.; Jones, V.C. Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) Negotiations; Congressional Research Service Report R43387; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, J.A. Transatlantic conflict and cooperation concerning trade issues. Manag. Glob. Transit. 2014, 12, 201–217. [Google Scholar]

- Wróbel, A. Specyfika liberalizacji handlu rolnego w TTIP (Agricultural Trade Liberalisation and the Logic of the TTIP). In TTIP. Transatlantyckie Partnerstwo w Dziedzinie Handlu i Inwestycji. Nowy Etap Instytucjonalizacji Współpracy UE-USA (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership—A New Stage of Institutionalization of the EU-US Cooperation); Dunin-Wąsowicz, M., Jarczewska, A., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; pp. 214–230. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, L.J.; Garcia-Duran Huet, P. TTIP negotiations: Interest groups, anti-TTIP civil society campaigns and public opinion. J. Transatl. Stud. 2018, 16, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eken, I. The United States’ New Outlook on Transatlantic Partnership (US-European controversy). J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2020, 22, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzyck, K.; Jarzębowski, S.; Petersen, B. Exploring Sustainable Aspects Regarding the Food Supply Chain, Agri-Food Quality Standards, and Global Trade: An Empirical Study among Experts from the European Union and the United States. Energies 2021, 14, 5987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszewski, T. Perspektywy transatlantyckiej strefy wolnego handlu (Prospects for the transatlantic free trade areas). In Współpraca Transatlantycka. Aspekty Polityczne, Ekonomiczne i Społeczne (Transatlantic Cooperation. Its Political, Economic and Social Aspects); Fiszer, J.M., Olszewski, P., Piskorska, B., Podraza, A., Eds.; Instytut Studiów Politycznych Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Fundacja im. Konrada Adenauera: Warsaw, Poland, 2014; pp. 135–151. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Francois, J.; Manchin, M.; Norberg, H.; Pindyuk, O.; Tomberger, P. Reducing Trans-Atlantic Barriers to Trade and Investment: An Economic Assessment; Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR): London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Trade SIA on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the EU and the USA; Annexes to the Interim Technical Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WTI. TTIP and the EU Member States. An Assessment of the Economic Impact of an Ambitious Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership at EU Member State Level; World Trade Institute: Bern, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fontagné, L.; Gourdon, J.; Jean, S. Transatlantic Trade: Whither Partnership, Which Economic Consequences? CEPII Policy Brief, 1; CEPII: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berden, K.G.; Francois, J.; Tamminen, S.; Thelle, M.; Wymenga, P. Non-Tariff Measures in EU-US Trade and Investment: An Economic Analysis; ECORYS: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Romagosa, H. Potential economic effects of TTIP for the Netherlands. De Econ. 2017, 165, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkonen, T. The principle of common but differentiated responsibility in Post-2012 climate negotiations. Rev. Eur. Community Int. Environ. Law 2009, 18, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunin-Wąsowicz, M. Analizy sektorowe państw Unii Europejskiej a TTIP (Sectoral Analyses of TTIP Conducted by the EU Member States). In Analiza Wpływu TTIP na Wybrane Sektory Polskiej Gospodarki (The Impact of TTIP on Selected Sectors of the Polish Economy—An Analysis); Dunin-Wąsowicz, M., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 14–53. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bureau, J.-C.; Disdier, A.-C.; Emlinger, C.; Felbermayr, G.; Fontagné, L.; Fouré, J.; Jean, S. Risks and Opportunities for the EU Agri-food Sector in a Possible EU-US Trade Agreement; CEPII Research Report No. 2014-01; CEPII: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2014/514007/AGRI_IPOL_STU(2014)514007_EN.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Poczta-Wajda, A.; Sapa, A. Potential trade effects of tariff liberalization under the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) for the EU agri-food sector. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2017, 2, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, K. Tariff barriers to the EU and the US agri-food trade in the view of the TTIP negotiation. In Agrarian Perspectives XXV. Global and European Challenges for Food Production, Agribusiness and Rural Economy, Proceedings of the 25th International Scientific Conference; Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Faculty of Economics and Management: Prague, Czech Republic, 2016; pp. 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, K. Agricultural support policy as a determinant of international competitiveness: Evidence from the EU and US. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference “Economic Science for Rural Development” No 47, Jelgava, Latvia, 9–11 May 2018; Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies: Jelgava, Latvia, 2018; pp. 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, K.; Poczta, W. Agricultural Resources and their Productivity: A Transatlantic Perspective. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2020, 23, 18–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, K.; Smutka, L.; Kotyza, P. Agricultural Potential of the EU Countries: How Far Are They from the USA? Agriculture 2021, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemejer, J.; Michałek, J.J.; Pawlak, K. Ocena wpływu podpisania TTIP na polski sektor rolny i spożywczy (Assessment of TTIP’s Effects on the Polish Agricultural and Food Sector). In Analiza Wpływu TTIP na Wybrane Sektory Polskiej Gospodarki (The Impact of TTIP on Selected Sectors of the Polish Economy—An Analysis); Dunin-Wąsowicz, M., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 120–197. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Serrão, A. A comparison of agricultural productivity among European countries. Mediterr. J. Econ. Agric. Environ. 2003, 2, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen, J.F.M.; Vranken, L. Reforms and agricultural productivity in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Republics: 1989–2005. J. Product. Anal. 2010, 33, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poczta, W.; Pawlak, K. Potenzielle Wettbewerbsfächigkeit und Konkurrenzposition des polnischen Landwirtschaftssektors auf dem Europäischen Binnenmarkt (Potential competitiveness and competitive position of the Polish agri-food sector on the Single European Market). Ber. Landwirtsch. 2011, 89, 134–169. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Baer-Nawrocka, A.; Markiewicz, N. Relacje między czynnikami produkcji a efektywność wytwarzania w rolnictwie Unii Europejskiej (Production potential and agricultural effectiveness in European Union countries). J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2013, 3, 5–16. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, K. Agricultural productivity, trade and food self-sufficiency: Evidence from Poland, the EU and the US. In Agrarian Perspectives XXVII. Food Safety—Food Security, Proceedings of the 27th International Scientific Conference, Prague, Czech Republic, 19–20 September 2018; Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Faculty of Economics and Management: Prague, Czech Republic, 2018; pp. 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Baráth, L.; Fertő, I. Productivity and Convergence in European Agriculture. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 68, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszewska, J.; Rembisz, W. Relacje czynnikowe i produktywnościowe w rolnictwie Unii Europejskiej (Factor and Productivity Relations in EU Agriculture). Wieś Rol. 2019, 2, 31–55. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijek, A.; Kijek, T.; Nowak, A.; Skrzypek, A. Productivity and its convergence in agriculture in new and old European Union member states. Agric. Econ. Czech 2019, 65, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożek, J.; Nowak, C.; Zioło, M. Changes in agrarian structure in the EU during the period 2010–2016 in terms of typological groups of countries. Agric. Econ. Czech 2020, 66, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, M.; Smędzik-Ambroży, K. Economic resources versus the efficiency of different types of agricultural production in regions of the European Union. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraž. 2020, 33, 1036–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimiani, A.; Carbone, A.; Costantini, V.; Henke, R. Agri-food exports in the enlarged European Union. Agric. Econ. Czech 2012, 58, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraresi, L.; Banterle, A. Agri-food Competitive Performance in EU Countries: A Fifteen-Year Retrospective. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bojnec, Š.; Fertő, I. Agri-Food Export Competitiveness in European Union Countries. J. Common Mark. Stud. 2015, 53, 476–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojnec, Š.; Fertő, I. Are new EU member states catching up with older ones on global agri-food markets? Post-Communist Econ. 2015, 27, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojnec, Š.; Fertő, I. Drivers of the duration of comparative advantage in the European Union’s agri-food exports. Agric. Econ. Czech 2018, 64, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojnec, Š.; Fertő, I. Agri-food comparative advantages in the European Union countries by value chains before and after enlargement towards the East. Agraarteadus J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 30, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juchniewicz, M.; Łukiewska, K. Competitive position of the food industry of the European Union on the global market. Acta Sci. Pol. Oeconomia 2015, 14, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, K. Importance and comparative advantages of the EU and US agri-food sector in world trade in 1995–2015. Zesz. Nauk. Szk. Gł. Gospod. Wiej. Warsz. Probl. Rol. Świat. 2017, 17, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnands, J.H.M.; van der Meulen, B.M.J.; Poppe, K.J. Competitiveness of the European Food Industry. An Economic and Legal Assessment 2007; European Commission Project No. 30777; LEI: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wijnands, J.H.M.; Bremmers, H.J.; van der Meulen, B.M.J.; Poppe, K.J. An economic and legal assessment of the EU food industry’s competitiveness. Agribusiness 2008, 24, 417–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnands, J.H.M.; Verhoog, D. Competitiveness of the EU Food Industry. Ex-Post Assessment of Trade Performance Embedded in International Economic Theory; LEI Report 2016-018; LEI Wageningen UR (University & Research Centre): Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, K. Stan przemysłu spożywczego w Polsce na tle pozostałych krajów UE i USA (The State of Food Industry in Poland against the Rest of the European Union Countries and the US). Zesz. Nauk. Szk. Gł. Gospod. Wiej. Warsz. Probl. Rol. Świat. 2016, 16, 313–324. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, K. Zdolność konkurencyjna przemysłu spożywczego krajów UE, USA i Kanady na rynku światowym (Competitive Capacity of the EU, the US and Canadian Food Industry on the World Market). Zesz. Nauk. Szk. Gł. Gospod. Wiej. Warsz. Probl. Rol. Świat. 2018, 18, 248–261. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, K.; Poczta, W. Pozycja konkurencyjna polskiego sektora rolno-spożywczego na Jednolitym Rynku Europejskim (Competitive Position of the Polish Agri-Food Sector on the EU Market). Wieś Rol. 2008, 4, 81–102. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, K.; Jabkowski, D. Przewagi komparatywne USA w eksporcie wybranych surowców roślinnych na Jednolity Rynek Europejski (Comparative Advantages of the US in the Export of Selected Plant Raw Materials to the Single European Market). Zesz. Nauk. Szk. Gł. Gospod. Wiej. Warsz. Probl. Rol. Świat. 2018, 18, 370–381. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, K. Comparative advantages of the Polish agri-food sector on the US market. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Scientific Conference “Economic Sciences for Agribusiness and Rural Economy”, Warsaw, Poland, 7–8 June 2018; Warsaw University of Life Sciences—SGGW, Faculty of Economic Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reed, M.R.; Marchant, M.A. The global competitiveness of the U. S. food processing industry. Northeast. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 1992, 21, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latruffe, L. Competitiveness, Productivity and Efficiency in the Agricultural and Agri-Food Sectors; OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Working Papers No. 30; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Siggel, E. International competitiveness and comparative advantage: A survey and a proposal for measurement. J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2006, 6, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohberg, K.; Hartmann, M. Comparing Measures of Competitiveness; Discussion Paper No. 2; Institute of Agricultural Development in Central and Eastern Europe (IAMO): Halle (Saale), Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Balassa, B. Trade Liberalisation and “Revealed” Comparative Advantage. Manch. Sch. 1965, 33, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K. China’s Economic Growth, Changing Comparative Advantages and Agricultural Trade. Rev. Mark. Agric. Econ. 1990, 58, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Waheed, A. Trade competitiveness of Pakistan: Evidence from the revealed comparative advantage approach. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2017, 27, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, I. Comparative advantages in Polish export to the European Union—food products vs selected groups of non-food products. Oeconomia Copernic. 2018, 9, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollrath, T.L. Competitiveness and Protection in World Agriculture; Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 56; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1989.

- Szczepaniak, I. Changes in comparative advantages of the Polish food sector in world trade. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2019, 14, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erokhin, V.; Diao, L.; Du, P. Sustainability-Related Implications of Competitive Advantages in Agricultural Value Chains: Evidence from Central Asia—China Trade and Investment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojnec, Š. Trade and Revealed Comparative Advantage Measures: Regional and Central and East European Agricultural Trade. East. Eur. Econ. 2001, 39, 72–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytko, A. Środkowoeuropejskie Porozumienie Wolnego Handlu CEFTA jako Studium Rozwoju Integracji Europejskiej w Sferze Rolnictwa i Gospodarki Żywnościowej (Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) as a Study of the Development of European Integration in the Field of Agriculture and Food Economy); Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2003. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Hambalková, M. The factors of competitiveness and the quantification of their impact on the export efficiency of grape and wine in the Slovak Republic. Agric. Econ. Czech 2006, 52, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimpoies, L. An analysis of Moldova’s agri-food products competitiveness on the EU market. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 10, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kita, K. Międzynarodowa pozycja konkurencyjna polskich artykułów rolno-spożywczych na rynnach wybranych krajów azjatyckich—stan i perspektywy (The International Competitive Position of Polish Agri-Food Products on the Selected Asian Markets—Current Status and Prospects). Zesz. Nauk. Szk. Gł. Gospod. Wiej. Warsz. Probl. Rol. Świat. 2016, 16, 153–166. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Babu, S.C.; Shishodia, M. Analytical Review of African Agribusiness Competitiveness. Afr. J. Manag. 2017, 3, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posłuszny, K. Konkurencyjność międzynarodowa jako miara skuteczności restrukturyzacji przemysłu (International competitiveness as a measure of industry restructuring effectiveness). Ekon. Menedż. 2011, 9, 49–61. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, K. Revealed comparative advantage and the alternatives as measures of international specialization. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2015, 5, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K. Revealed Comparative Advantage and the Alternatives as Measures of International Specialisation; DRUID Working Paper No. 98–30; Danish Research Unit for Industrial Dynamics, Copenhagen Business School, Department of Industrial Economics and Strategy: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dalum, B.; Laursen, K.; Villumsen, G. Structural Change in OECD Export Specialisation Patterns: De-specialisation and ’stickiness’. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 1998, 12, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, T. Comparative Advantage: Theory, Empirical Measures and Case Studies. Rev. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2009, 4, 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ishchukova, N.; Smutka, L. “Revealed” Comparative Advantage: Products Mapping of the Russian Agricultural Exports in Relation to Individual Regions. Acta Sci. Pol. Oeconomia 2014, 13, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Smutka, L.; Maitah, M.; Svatoš, M. Changes in the Czech agrarian foreign trade competitiveness—different groups of partners’ specifics. Agric. Econ. Czech 2018, 64, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verter, N.; Zdráhal, I.; Bečvářová, V.; Grega, L. ‘Products mapping’ and trade in agri-food products between Nigeria and the EU28. Agric. Econ. Czech 2020, 66, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdráhal, I.; Verter, N.; Lategan, F. ‘Products Mapping’ of South Africa’s Agri-food trade with the EU28 and Africa. AGRIS Online Pap. Econ. Inform. 2020, 12, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comext-Eurostat. International Trade Data. Available online: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/newxtweb/ (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Yurik, S.; Pushkin, N.; Yurik, V.; Halík, J.; Smutka, L. Analysis of Czech agricultural exports to Russia using mirror statistics. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2020, 8, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafay, G. The Measurement of Revealed Comparative Advantages. In International Trade Modeling; Dagenais, M.G., Muet, P.A., Eds.; Chapman & Hill: London, UK, 1992; pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, K.; Poczta, W. Handel wewnątrzgałęziowy w wymianie produktami rolno-spożywczymi UE z USA (Intra-industry Trade in Agri-food Products between the EU and US). Zesz. Nauk. Szk. Gł. Gospod. Wiej. Warsz. Probl. Rol. Świat. 2019, 19, 93–102. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvacruz, J.; Reed, M. Identifying the best market prospects for US agricultural exports. Agribusiness 1993, 9, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loertscher, R.; Wolter, F. Determinants of intra-industry trade: Among countries and across industries. Rev. World Econ. Weltwirtsch. Arch. 1980, 116, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jámbor, A. Country- and industry-specific determinants of intra-industry trade in agri-food products in the Visegrad countries. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2015, 117, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łapińska, J. Determinant factors of intra-industry trade: The case of Poland and its European Union trading partners. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2016, 11, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojnec, Š.; Fertő, I. Patterns and drivers of the agri-food intra-industry trade of European Union countries. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- WITS-TRAINS. Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/default.aspx (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Thompson-Lipponen, C.; Greenville, J. The Evolution of the Treatment of Agriculture in Preferential Trade Agreements; OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers No. 126; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Raimondi, V.; Falco, C.; Curzi, D.; Olper, A. Trade effects of geographical indication policy: The EU case. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 71, 330–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźnar, A. TTIP a interesy Unii Europejskiej i Stanów Zjednoczonych w zakresie własności intelektualnej (TTIP and the interests of the European Union and the United States in the field of intellectual property). In Partnerstwo Transatlantyckie. Wnioski dla Polski (Transatlantic Partnership. Conclusions for Poland); Czarny, E., Słok-Wódkowska, M., Eds.; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 83–100. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, A. What outcome to expect on geographical indications in the TTIP free trade negotiations with the United States? In Intellectual Property Rights for Geographical Indications: What Is at Stake in the TTIP? Arfini, F., Mancini, M., Veneziani, M., Donati, M., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2016; pp. 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- WTO. Integrated Trade Intelligence Portal (I-TIP). Available online: http://i-tip.wto.org/goods/Forms/TableView.aspx (accessed on 13 August 2021).

| Author | Scenario Assumptions | Estimated Changes (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tariff Cut (%) | Reduction of Non-Tariff Barriers to Trade in Goods and Services (%) | GDP in the EU | GDP in the US | Export from the EU to the US | Export from the US to the EU | Export from the EU in Total | Export from the US in Total | Import to the EU in Total | Import to the US in Total | |

| Berden et al. [16] | not assumed | 50 | +0.72 per year | +0.28 per year | ne | ne | +2.07 | +6.06 | +2.00 | +3.93 |

| Fontagné, Gourdon, Jean [15] | 100 | 25 | +0.3 | +0.3 | +49.0 | +52.5 | +2.3 a/+7.6 b | +10.1 | +2.2 a/+7.4 b | +7.5 |

| Francois et al. [12] | 98 | 10 | +0.27 | +0.21 | +16.16 | +23.20 | +3.37 b | +4.75 | +2.91 b | +2.81 |

| 100 | 25 | +0.48 | +0.39 | +28.03 | +36.57 | +5.91 b | +8.02 | +5.11 b | +4.74 | |

| European Commission [13] | 100 | 25 c | +0.51 | +0.38 | +26.95 | +35.73 | +8.16 b | +11.43 | +7.39 b | +4.59 |

| WTI [14] | 100 | 25 | +0.5 per year | +0.4 per year | +28.0 | +37.0 | +6.0 | +8.0 | ne | ne |

| Rojas-Romagosa [17] | 100 | 50 | +1.2 | +0.9 | +111.4 | +119.0 | +6.3 | +21.4 | +9.0 | +23.8 |

| Author | Scenario Assumptions | Estimated Changes (%) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tariff Cut (%) | Reduction of Non-Tariff Barriers to Trade in Goods and Services (%) | Export from the EU to the US | Import from the US to the EU | Export from the EU to Third Countries | Export from the US in Total | Import to the EU From Third Countries | Import to the US in Total | |||||||

| A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | |||

| Fontagné, Gourdon, Jean [15] | 100 | 25 | +149.5 | ne | +168.5 | ne | +7.0 | ne | +12.6 | ne | −1.5 | ne | −0.8 | ne |

| Francois et al. [12] | 98 | 10 | +16.3 | +26.1 | +20.5 | +56.5 | +0.41 | +5.21 | +0.67 | +4.58 | +3.84 | +6.26 | +1.18 | +9.15 |

| 100 | 25 | +15.1 | +45.5 | +21.8 | +74.8 | +0.22 | +9.36 | +1.07 | +6.85 | +5.22 | +10.07 | +0.59 | +16.37 | |

| Bureau et al. [20] c | 100 | 0 | +18.5 | +30.7 | −0.1 | −0.5 | −0.4 | −0.6 | ||||||

| 100 | 25 | +56.4 | +116.3 | 0.0 | −1.5 | −1.5 | −1.7 | |||||||

| Poczta-Wajda, Sapa [21] | 100 | 0 | +8.5 | +9.2 | +0.78 | ne | +0.61 | ne | ||||||

| Section | Export | Import | Trade Balance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2020 | 2010 | 2020 | 2010 | 2020 | |||

| € Million | 2010 = 100 a | € Million | 2010 = 100 a | € Million | ||||

| I. Live animals; animal products | 1095.8 | 2403.3 | 1307.6 | 891.1 | 1099.8 | 208.7 | 204.7 | 1303.5 |

| II. Vegetable products | 1293.9 | 2477.9 | 1184.0 | 3158.5 | 5548.2 | 2389.7 | −1864.6 | −3070.3 |

| III. Animal or vegetable fats and oils and their cleavage products; prepared edible fats; animal or vegetable waxes | 637.4 | 1258.3 | 620.8 | 187.5 | 256.4 | 68.8 | 449.9 | 1001.9 |

| IV. Prepared foodstuffs; beverages, spirits and vinegar; tobacco and manufactured tobacco substitutes | 7598.8 | 15,081.3 | 7482.6 | 2190.2 | 2811.2 | 621.0 | 5408.5 | 12,270.1 |

| Total | 10,625.9 | 21,220.9 | 10,595.0 | 6427.4 | 9715.6 | 3288.3 | 4198.5 | 11,505.3 |

| HS | Product Group | 2010 | 2020 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export | Import | Trade Balance (€ Million) | Export | Import | Trade Balance (€ Million) | ||||||

| Value (€ Million) | Share (%) | Value (€ Million) | Share (%) | Value (€ Million) | Share (%) | Value (€ Million) | Share (%) | ||||

| 01 | Live animals | 150.7 | 1.4 | 69.0 | 1.1 | 81.7 | 349.1 | 1.6 | 85.8 | 0.9 | 263.3 |

| 02 | Meat and edible meat offal | 178.8 | 1.7 | 97.7 | 1.5 | 81.1 | 404.7 | 1.9 | 158.5 | 1.6 | 246.2 |

| 03 | Fish and crustaceans, molluscs and other aquatic invertebrates | 147.1 | 1.4 | 634.4 | 9.9 | −487.3 | 439.7 | 2.1 | 744.8 | 7.7 | −305.1 |

| 04 | Dairy produce; birds’ eggs; natural honey | 588.5 | 5.5 | 46.4 | 0.7 | 542.2 | 1105.3 | 5.2 | 34.5 | 0.4 | 1 070.7 |

| 05 | Products of animal origin, not elsewhere specified | 30.7 | 0.3 | 43.6 | 0.7 | −12.9 | 104.6 | 0.5 | 76.1 | 0.8 | 28.5 |

| 06 | Live trees and other plants | 198.9 | 1.9 | 76.0 | 1.2 | 122.8 | 227.5 | 1.1 | 56.6 | 0.6 | 170.9 |

| 07 | Edible vegetables and certain roots and tubers | 135.5 | 1.3 | 118.4 | 1.8 | 17.1 | 376.1 | 1.8 | 236.2 | 2.4 | 139.8 |

| 08 | Edible fruit and nuts | 104.7 | 1.0 | 1166.7 | 18.2 | −1062.1 | 151.0 | 0.7 | 2543.7 | 26.2 | −2392.7 |

| 09 | Coffee, tea, mate and spices | 377.6 | 3.6 | 13.9 | 0.2 | 363.8 | 489.2 | 2.3 | 43.3 | 0.4 | 445.8 |

| 10 | Cereals | 24.8 | 0.2 | 373.6 | 5.8 | −348.7 | 80.2 | 0.4 | 306.7 | 3.2 | −226.5 |

| 11 | Products of the milling industry | 145.4 | 1.4 | 16.1 | 0.3 | 129.2 | 344.1 | 1.6 | 18.1 | 0.2 | 326.0 |

| 12 | Oil seeds and oleaginous fruits | 150.1 | 1.4 | 1280.3 | 19.9 | −1130.3 | 378.3 | 1.8 | 2213.4 | 22.8 | −1835.1 |

| 13 | Lac; gums, resins and other vegetable saps and extracts | 155.8 | 1.5 | 101.0 | 1.6 | 54.8 | 416.6 | 2.0 | 127.8 | 1.3 | 288.8 |

| 14 | Vegetable planting materials; vegetable products not elsewhere specified | 1.1 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 0.2 | −11.4 | 15.0 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 12.6 |

| 15 | Animal or vegetable fats and oils | 637.4 | 6.0 | 187.5 | 2.9 | 449.9 | 1258.3 | 5.9 | 256.4 | 2.6 | 1001.9 |

| 16 | Preparations of meat or of fish | 117.9 | 1.1 | 44.9 | 0.7 | 73.0 | 279.1 | 1.3 | 38.3 | 0.4 | 240.8 |

| 17 | Sugars and sugar confectionery | 156.8 | 1.5 | 35.4 | 0.6 | 121.3 | 438.8 | 2.1 | 57.8 | 0.6 | 381.0 |

| 18 | Cocoa and cocoa preparations | 622.0 | 5.9 | 15.1 | 0.2 | 606.8 | 707.8 | 3.3 | 38.1 | 0.4 | 669.7 |

| 19 | Preparations of cereals | 490.2 | 4.6 | 38.7 | 0.6 | 451.5 | 1467.9 | 6.9 | 54.0 | 0.6 | 1413.9 |

| 20 | Preparations of vegetables, fruit or nuts | 538.3 | 5.1 | 189.7 | 3.0 | 348.6 | 1283.9 | 6.1 | 185.7 | 1.9 | 1098.2 |

| 21 | Miscellaneous edible preparations | 322.6 | 3.0 | 299.6 | 4.7 | 23.0 | 1102.2 | 5.2 | 656.9 | 6.8 | 445.3 |

| 22 | Beverages, spirits and vinegar | 5178.0 | 48.7 | 740.7 | 11.5 | 4437.3 | 9311.8 | 43.9 | 1058.7 | 10.9 | 8253.1 |

| 23 | Residues and waste from the food industries; prepared animal fodder | 93.9 | 0.9 | 514.9 | 8.0 | −421.0 | 398.3 | 1.9 | 434.7 | 4.5 | −36.4 |

| 24 | Tobacco and manufactured tobacco substitutes | 79.2 | 0.7 | 311.2 | 4.8 | −232.0 | 91.6 | 0.4 | 287.0 | 3.0 | −195.4 |

| Total | 10,625,9 | 100.0 | 6427.4 | 100.0 | 4198.5 | 21,220.9 | 100.0 | 9715.6 | 100.0 | 11,505.3 | |

| HS | Product Group | 2010 | 2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCA a | RC b | RSCA c | TBI d | RCA a | RC b | RSCA c | TBI d | ||

| 01 | Live animals | 1.32 | 0.56 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 1.86 | 1.24 | 0.30 | 0.61 |

| 02 | Meat and edible meat offal | 1.11 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 1.17 | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.44 |

| 03 | Fish and crustaceans, molluscs and other aquatic invertebrates | 0.14 | −3.93 | −0.75 | −0.62 | 0.27 | −2.62 | −0.57 | −0.26 |

| 04 | Dairy produce; birds’ eggs; natural honey | 7.68 | 4.08 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 14.65 | 5.37 | 0.87 | 0.94 |

| 05 | Products of animal origin, not elsewhere specified | 0.43 | −1.71 | −0.40 | −0.17 | 0.63 | −0.93 | −0.23 | 0.16 |

| 06 | Live trees and other plants | 1.58 | 0.92 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 1.84 | 1.22 | 0.30 | 0.60 |

| 07 | Edible vegetables and certain roots and tubers | 0.69 | −0.74 | −0.18 | 0.07 | 0.73 | −0.63 | −0.16 | 0.23 |

| 08 | Edible fruit and nuts | 0.05 | −5.83 | −0.90 | −0.84 | 0.03 | −7.21 | −0.95 | −0.89 |

| 09 | Coffee, tea, mate and spices | 16.49 | 5.61 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 5.17 | 3.28 | 0.68 | 0.84 |

| 10 | Cereals | 0.04 | −6.43 | −0.92 | −0.88 | 0.12 | −4.24 | −0.79 | −0.59 |

| 11 | Products of the milling industry | 5.45 | 3.39 | 0.69 | 0.80 | 8.73 | 4.33 | 0.79 | 0.90 |

| 12 | Oil seeds and oleaginous fruits | 0.07 | −5.29 | −0.87 | −0.79 | 0.08 | −5.10 | −0.85 | −0.71 |

| 13 | Lac; gums, resins and other vegetable saps and extracts | 0.93 | −0.14 | −0.03 | 0.21 | 1.49 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.53 |

| 14 | Vegetable planting materials; vegetable products not elsewhere specified | 0.05 | −5.82 | −0.90 | −0.83 | 2.90 | 2.13 | 0.49 | 0.73 |

| 15 | Animal or vegetable fats and oils | 2.06 | 1.44 | 0.35 | 0.55 | 2.25 | 1.62 | 0.38 | 0.66 |

| 16 | Preparations of meat or of fish | 1.59 | 0.92 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 3.34 | 2.41 | 0.54 | 0.76 |

| 17 | Sugars and sugar confectionery | 2.68 | 1.97 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 3.47 | 2.49 | 0.55 | 0.77 |

| 18 | Cocoa and cocoa preparations | 24.86 | 6.43 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 8.51 | 4.28 | 0.79 | 0.90 |

| 19 | Preparations of cereals | 7.66 | 4.07 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 12.44 | 5.04 | 0.85 | 0.93 |

| 20 | Preparations of vegetables, fruit or nuts | 1.72 | 1.08 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 3.17 | 2.30 | 0.52 | 0.75 |

| 21 | Miscellaneous edible preparations | 0.65 | −0.86 | −0.21 | 0.04 | 0.77 | −0.53 | −0.13 | 0.25 |

| 22 | Beverages, spirits and vinegar | 4.23 | 2.88 | 0.62 | 0.75 | 4.03 | 2.79 | 0.60 | 0.80 |

| 23 | Residues and waste from the food industries; prepared animal fodder | 0.11 | −4.41 | −0.80 | −0.69 | 0.42 | −1.74 | −0.41 | −0.04 |

| 24 | Tobacco and manufactured tobacco substitutes | 0.15 | −3.74 | −0.73 | −0.59 | 0.15 | −3.85 | −0.75 | −0.52 |

| Group | 2010 | 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share in Total Export (%) | Share in Total Import (%) | Trade Balance (€ Million) | Share in Total Export (%) | Share in Total Import (%) | Trade Balance (€ Million) | |

| Group A | 88.3 | 24.4 | 7809.2 | 85.3 | 22.8 | 15,883.0 |

| Group B | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Group C | 5.8 | 8.1 | 94.9 | 9.8 | 17.4 | 381.7 |

| Group D | 5.9 | 67.5 | −3705.6 | 4.9 | 59.8 | −4759.4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pawlak, K. Competitiveness of the EU Agri-Food Sector on the US Market: Worth Reviving Transatlantic Trade? Agriculture 2022, 12, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12010023

Pawlak K. Competitiveness of the EU Agri-Food Sector on the US Market: Worth Reviving Transatlantic Trade? Agriculture. 2022; 12(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12010023

Chicago/Turabian StylePawlak, Karolina. 2022. "Competitiveness of the EU Agri-Food Sector on the US Market: Worth Reviving Transatlantic Trade?" Agriculture 12, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12010023

APA StylePawlak, K. (2022). Competitiveness of the EU Agri-Food Sector on the US Market: Worth Reviving Transatlantic Trade? Agriculture, 12(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12010023