1. Introduction

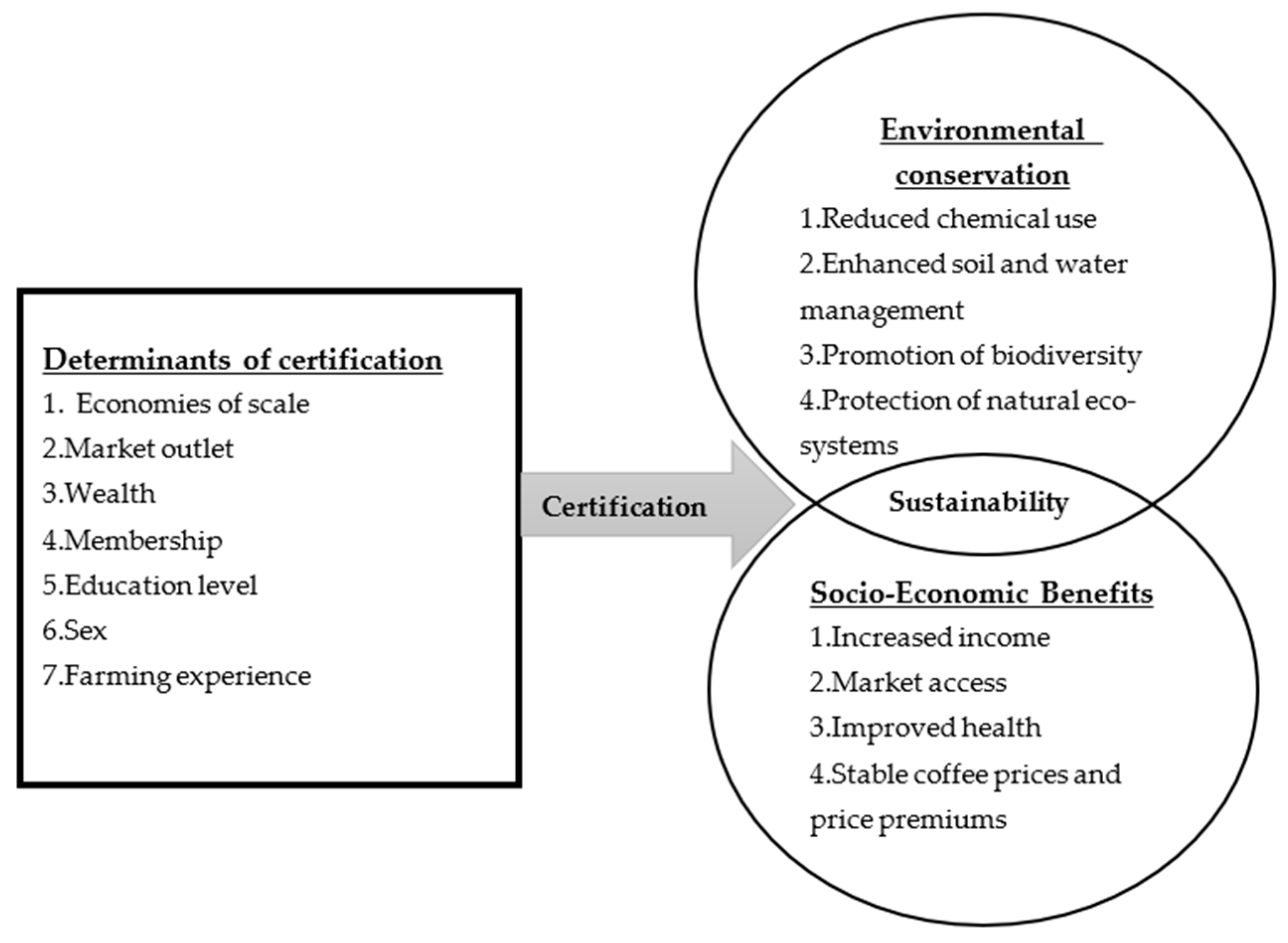

Certification is an important economic tool that is used to promote social-economic and environmental conservation objectives in the world [

1]. It is used to stimulate quality and sustainability standards where consumers pay price premiums to promote social and economic change and environmental sustainability in the world [

2,

3]. Through these arrangements, farmers adhere to set standards so that they can benefit from price premiums and other related advantages associated with certification. However, certification is voluntary and it is used as a tool to access markets while attaining sustainability goals within the commodity supply chains. Farmers are thus required to comply with the set sustainability measures and regulations in order to enable them to access the benefits of certification [

4].

Certification involves a number of stakeholders, hence there are various certification schemes covering a range of issues within the sustainability framework. For example, retailers introduce quality standards responding to the consumers’ requirements; non-governmental organizations focus on achieving suitability goals; and governments in exporting countries aim at promoting a sustainable crop commodity industry. Other certification schemes are developed by specific product industries, such as the coffee industry with an interest in promoting coffee products [

3]. This is done to achieve sustainable development. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO [

5], sustainable development is “the management and conservation of the natural resource base, and the orientation of technological and institutional change in such a manner as to ensure the attainment and continued satisfaction of human needs for present and future generations. Such sustainable development (in the agriculture sector in particular) conserves land, water, plant and animal genetic resources, in environmentally non-degrading, technologically appropriate, economically viable and socially acceptable way”. Therefore, retailers, non-governmental organizations, governments, and other actors of the private sector have developed certification schemes aimed at achieving sustainable development.

For coffee, the most widely used certification standards are Fairtrade (according to Fair Trade Labelling Organization International), organic (according to the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements), 4C (Common Code for the Coffee Community), and Rainforest Alliance, which was merged with UTZ, certified in January 2018 [

3,

6,

7]. Some private companies, such as Coffee and Farmer Equity (C.A.F.E) Practices by Starbucks and Nespresso AAA, provide their own coffee certifications. There are also many others, such as Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (SMBC) Bird Friendly Certification, and Demeter, just to mention a few. These certification schemes provide independent, credible, traceable, and innovative solutions for sustainable supply chains of coffee [

3,

8]. They ensure that farmers produce certified coffee for specific intended markets. Certified coffee is intended to be grown in a healthy environment, it is economically viable to farmers, and promotes social equity among farmers and other workers within the coffee supply chain [

8].

Coffee certification schemes work along three main sustainability dimensions of social, economic, and environmental conservation. Social and economic benefits include access to markets, price premiums, better trading conditions, and stabilization in coffee prices [

7,

8]. Environmental conservation is enhanced through practices such as reduced use of agrochemicals, water conservation, soil erosion, energy use, and biodiversity conservation [

7,

9]. Additionally, the benefits of certification can extend to increased yields and better management of farmer associations [

1]. This is because some certification schemes such as Fairtrade, which is granted to cooperatives and associations and not to individual farmers, are accompanied by improved management of collective action groups.

Certification has made progress in the world and continues to show its importance due to the increasing demand for certified coffee by buyers in consuming countries. The demand for sourcing healthier and sustainably grown coffee has grown in recent years [

10]. Therefore, many coffee-producing countries in the world are supplying sustainably grown coffee to consumers. Tanzania is one of the developing countries supplying non-sustainable and sustainably grown coffee, including organic, rainforest-certified, and fair-traded coffee.

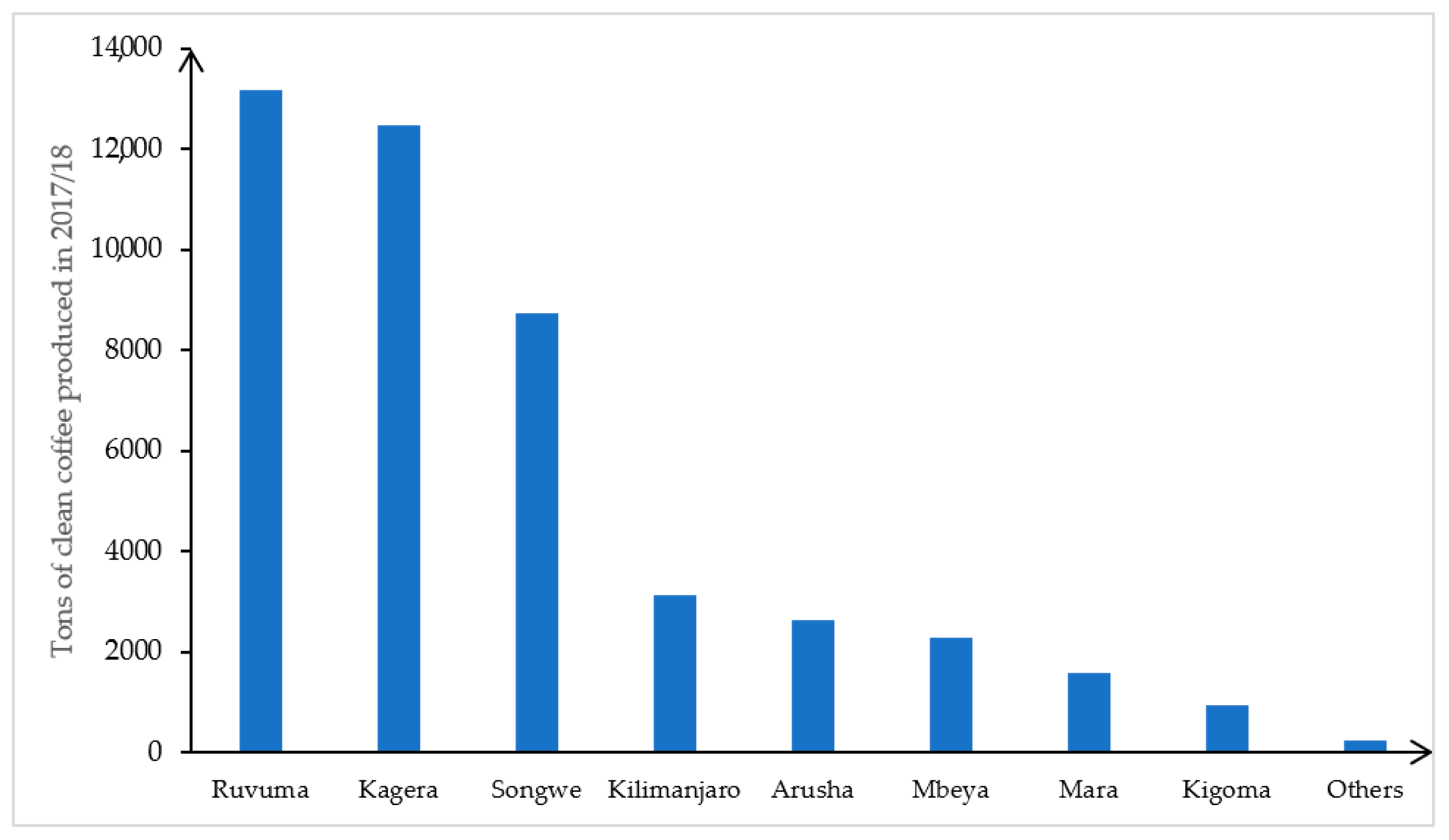

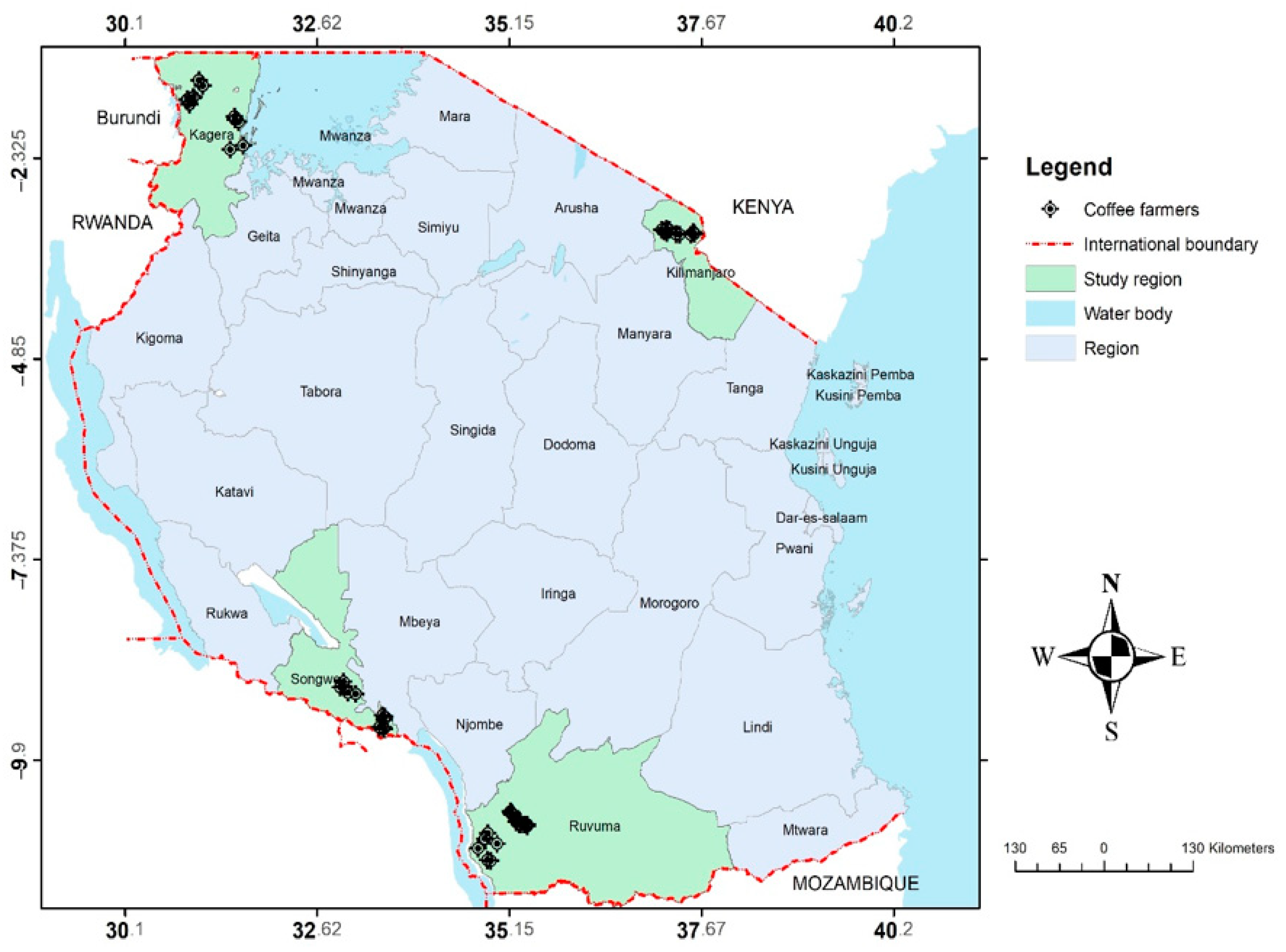

Coffee production in Tanzania started in 1898. The crop was first introduced in Kilimanjaro region, Northern zone of Tanzania by Catholic missionaries, and the crop is now grown in three zones of the country [

11]. These are the Northern zone made up of Kilimanjaro, Arusha, and Manyara regions; the Western zone made up of Kagera, Mara, and Kigoma regions; and the Southern highlands zone made up of Mbeya, Songwe, and Ruvuma regions. There are also emerging regions which have started to grow coffee in the Southern highlands (i.e., Iringa and Rukwa regions). Other coffee-producing regions are shown in

Figure 1.

There are two types of coffee grown in Tanzania, namely, Robusta (

Coffea canephora L. (Gentianales: Rubiaceae)) and Arabica (

Coffea arabica L.). Arabica coffee makes up about 70% of the total coffee produced in Tanzania. The Arabica coffee produced in Tanzania is of Colombian origin, “Colombian Mild Arabica”, which is used as a filler with other coffee types. Robusta coffee makes up 30% of the total coffee produced in the country [

12]. The level of coffee production in the country has increased from 33,000 tons in 1961 to 51,529 tons of green coffee (859 thousand 60 kg bags) in 2019 (FAO, 2020) (

Figure 2). The coffee production trajectory reached its increasing trend in the year 2000 to 2005, attaining a production level of 95,390 tons of green coffee, which was the highest in Tanzania coffee production history.

Tanzania has continued producing coffee and it is now among the top five coffee-producing countries in Africa. Africa makes up about 11% of the total global coffee production with Ethiopia, Uganda, Côte d’Ivoire, Madagascar, and Tanzania being the top five coffee producers [

13]. These five countries produce about 76% of the total coffee produced in Africa [

14]. Tanzania contributes about 1.7% to the total share of coffee production in the world [

15]. Coffee production in Tanzania is dominated by small-scale farmers (90%).

Tanzania experiences a positive static export trend for coffee. The country exports about 93% of the total coffee produced [

12]. For example, Tanzania exported coffee worth USD 165 million in the year 2019 [

16]. Available statistics indicate that about 70% of the Tanzania coffee is exported to six markets, which are Germany, Italy, the United States of America, Japan, Belgium, and the United Kingdom [

16]. The coffee trade is increasing due to favorable Arabica coffee prices and the accessibility of the country to niche export coffee markets. These niche export markets are Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance, and organic coffee markets [

7]. For example, the Arabica price increased by 10.3% for the coffee exported by Tanzania in the year 2020 [

17].

Tanzania, as with many other coffee-producing countries in the world, accesses niche export coffee markets by complying with quality and standards set in these markets. Standards set in these markets include sustainability standards. The main certification schemes operating in Tanzania are Organic, Fairtrade, and Rainforest Alliance. There are also specific companies’ certifications in Tanzania such as C.A.F.E Practices by Starbucks. All these certification schemes ensure that coffee sourced from Tanzania is healthier and sustainably grown.

Despite an increasing demand for sustainably sourced coffee, the level of certified coffee production has been declining in the world. Available statistics show that in the period of 2014 to 2018 the production of certified coffee dropped by 15.1% [

18]. In the same period, the area under certified coffee production also dropped by 12.2%. Certified coffee represented a 25.8% share of the global total coffee production by the year 2018 [

3]. Likewise, in Tanzania, as one of the coffee-producing countries, the trend is the same.

Certification schemes are charged with being ineffective, especially in sustainability awareness, transparency, and monitoring of social, environmental, and economic impacts [

19]. In many coffee-producing countries, the overall impact of certification schemes on the coffee farmers has been hard to establish [

1,

20,

21,

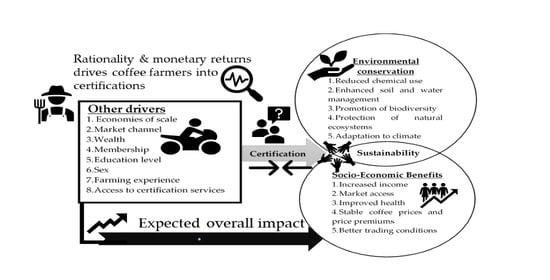

22]. Therefore, understanding the key constraints to certification, drivers, and impact of certification on the coffee sector in producer countries is important for crafting policies that will spur the production of sustainably grown coffee, social equity, and overall sustainability within the coffee supply chain. This study established the status, constraints, key drivers, and the impact of coffee certification in Tanzania.

3. Results

3.1. Socioeconomic Characteristics of Coffee Farmers

Participation of coffee farmers in certification schemes is low. Findings indicate that 70.5% of the farmers involved in the study were not participating in any certification scheme. The remaining proportion of farmers (29.5%) was in various certification schemes which are Organic, Rainforest Alliance, and Fairtrade certification schemes. Summary statistics of the sampled coffee farmers are provided in

Table 2. It is clear that most farmers who were not engaged in certification schemes were male adults. They were not specialized in coffee production, and had a high level of literacy. The results indicate significant variations between the level of specialization, age of the coffee farmer, and certification (

p < 0.05). The more specialized coffee farmers were engaged more in certification schemes than their counterpart coffee farmers with low levels of specialization. Additionally, old people (≤60 years) participated more in the certification schemes than adults (36–59 years) and youth (≤35 years). Generally, coffee production activities seemed to not be economically attractive to youth as only 11% of the farmers were youth. Land ownership might also be constraining youth from taking part in coffee production activities given the fact that the crop is perennial.

3.2. Coffee Farmers’ Participation in Collective Action

The participation of coffee farmers in collective actions facilitated access and decision to participate in certification schemes. Our results of analysis show that 91.3% of all the farmers have membership in various organizations. Many farmers who have membership in various organizations (98.1%) had membership in agricultural/livestock/fisheries farmer groups, including marketing groups such as agricultural and marketing cooperative societies. The other organizations with a high proportion of coffee farmers were trade and business associations and credit or microfinance groups, including saving and credit cooperative societies (SACCOS) and village saving and lending associations (VSLAs), with 13.7% and 12.6% of coffee farmers, respectively.

Additionally, participation in collective action facilitated collective sales of coffee and other agricultural produce. Results show that 89.5% of the coffee farmers used AMCOS as the key market outlet for their coffee. This shows that more coffee farmers who were members in various organizations and used AMCOS as their market outlets were in certification schemes (

Table 3). Coffee farmers who did not use AMCOS as their market outlet sold their coffee through middlemen, local villagers/neighbors, cottage processors, and other processing companies. In fact, many studies have reported the importance of agricultural farmers participating in collective action activities. Participation in collective action will not only make farmers benefit from collective sales but there are other advantages, including environmental conservation methods that can be obtained through participation in collective action. The studies by Barham and Chitemi [

33], Ochieng, Knerr [

34], and Twine, Rao [

35] have showed that sharing of technical knowledge and access to credit constituted several benefits that can be obtained through farmers’ participation in collective action.

3.3. Determinants of Certification Decisions among Coffee Farmers

Level of specialization, membership in organizations, and years of experience in coffee farming activities significantly influenced the decision to engage in the certification scheme under the two outcomes of household income and environmental conservation (

p < 0.05) (

Table 4). We used the level of specialization as the measure of economies of scale [

36]. The findings show that an increase in the level of specialization in coffee production activities increased the predicted probability for coffee farmers to become certified. This means that the more specialized the coffee farmers were, the more they were likely to become certified. However, farming households tend to pursue risk diversification objectives which reduce their level of specialization. Therefore, the most important indicator for coffee farmers to have a high chance of joining the certification schemes is economies of scale. Economies of scale indicate how a farmer can be able to intensify in the coffee production system. Farmers exercising a high level of intensification in coffee production may have a high chance of joining the certification scheme. Similarly, the study by Volsi, Telles [

37] indicated how specialization is essential for driving intensification in the production system.

Membership in organizations increased the predicted probability of becoming certified. Membership is the measure of participation in collective action. The participation of coffee farmers in collective action is an important method to obtain information on various niche markets that would lead to their involvement in certification schemes. Collective actions are also essential to spur knowledge transfer among the coffee farmers. Therefore, coffee farmers should be encouraged to have membership in various organizations which will support their coffee production and marketing activities, easing the chance of becoming certified. Participation in collective action is vital. Similarly, a study by Bravo-Monroy, Potts [

6] in Colombia indicated membership to be a key element in supporting coffee farmers to make decisions on certification.

Years of experience in coffee farming activities increased the chance of farmers making a decision to become certified. An increase in years of coffee farming experience increases the predicted probability of becoming certified. This means that the more experienced coffee farmers have a higher chance of becoming certified than the less experienced coffee farmers. Experience is always accompanied by improved knowledge and skills in farming practices. Experienced farmers have skills in managing coffee and other related activities. This increases the efficiency of their farming activities, leading to them being in a better position for making a decision to become certified.

Surprisingly, the wealth status of the coffee farmers reduced the chance of becoming certified. Findings indicate that an increase in the wealth of the coffee farmer reduces the predicted probability of becoming certified. The wealthier coffee farmers have a lower chance of joining the certification schemes. This is due to the fact that rich farmers have diversified their capital into investing in production of other better-paying crops such as banana, avocado, and other horticultural products.

In pursuing environmental conservation objectives, the market outlet used by the coffee farmers was found to be imperative. Coffee farmers selling through AMCOS were found to have a higher predicted probability of becoming certified than farmers who sold coffee via the other market outlets. Additionally, sex of the plot manager and level of education were not significant determinants of coffee farmers’ decision to engage in certification schemes.

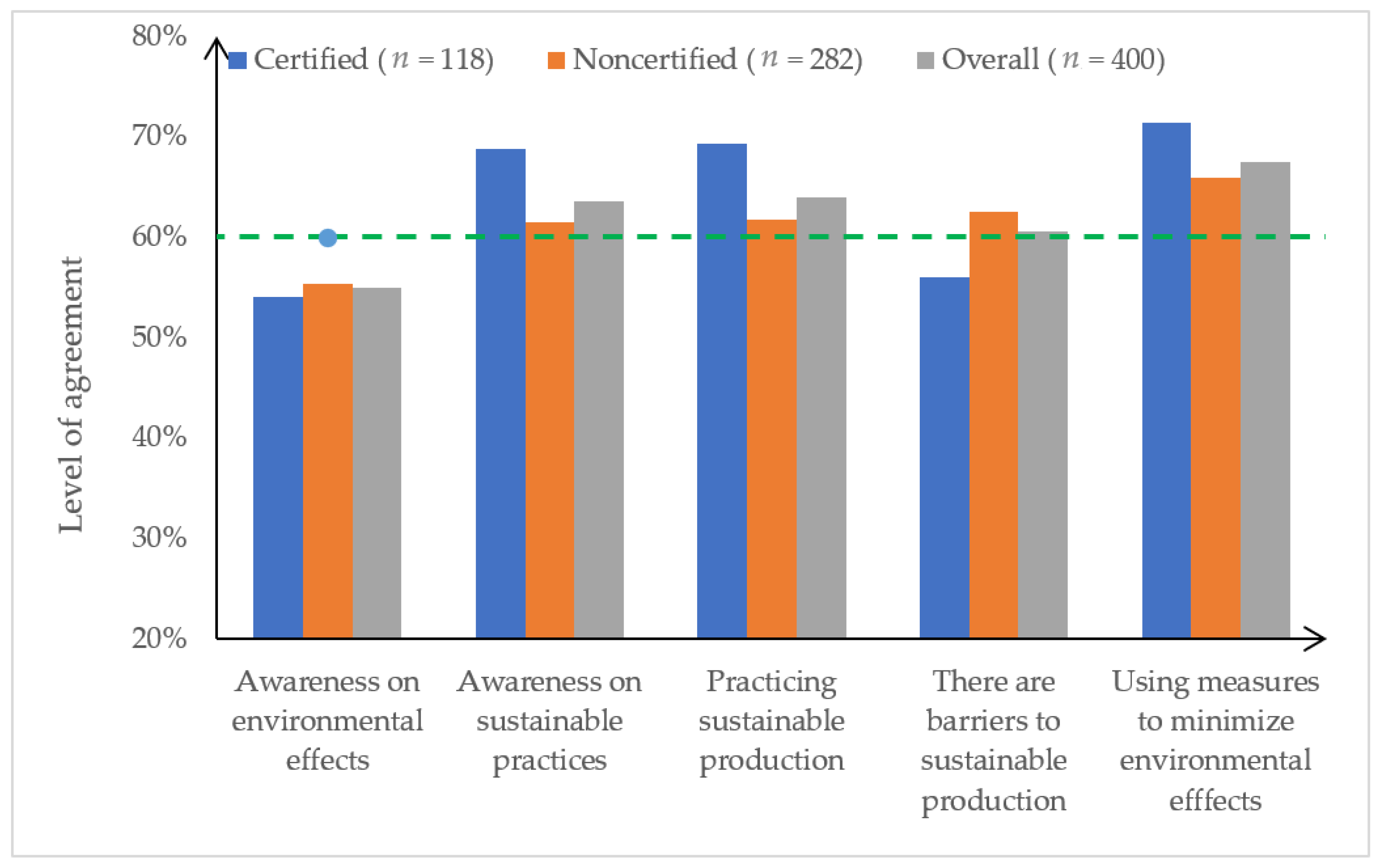

3.4. Coffee Farmers’ Awareness and Practice of Environmental Conservation

The study established the level of awareness and practice of environmental conservation among coffee farmers. Results indicated that 59.5% of coffee farmers are not aware of the environmental effects associated with coffee production activities. This brings out the need for environmental education to be provided to coffee farmers. Interestingly, the sustainable production practices for coffee that conserve the environment, general biodiversity, and ecosystem were known to many coffee farmers (53.6%), especially the certified coffee farmers (63.6%), and they practiced sustainable production. However, some non-certified coffee farmers (39.4%) indicated that they faced barriers in practicing sustainable coffee production/trade in their area. The barriers included inaccessibility to knowledge and some of the production inputs. Generally, certified coffee farmers face fewer barriers in practicing sustainable coffee production/trade in their area. They are more informed and they practice sustainable coffee production that conserves the environment, biodiversity, and ecosystems in contrast to the non-certified coffee farmers.

Nevertheless, many coffee farmers (65%) in both groups (77.1% for certified farmers and 59.9% for non-certified farmers) were found to be using measures that minimize environmental effects associated with coffee production. These measures include use of the mulching method for increasing water porosity, water retention capacity, and stability. This was practiced by 46% of the coffee farmers, of which many were certified farmers and were statistically significantly different from the non-certified farmers (

Table 5) (

p < 0.05). These methods conserve the environment and protect coffee farms from soil erosion. The other methods used to avoid soil erosion are planting trees, use of contours, construction of water streams, and terracing. However, this method was used by few (28.2%) farmers. The construction of water streams is used to avoid soil erosion and water loss. Additionally, many coffee farmers (92%) practice intercropping of coffee with leguminous crops to improve soil health by adding soil nutrients. The intercropping of coffee with trees and other beneficial plants enhances biodiversity in coffee production activities.

Water resource conservation is another method that was practiced by a few coffee farmers (8.8%) for minimizing environmental effects associated with coffee production and did not vary between the two groups. The practices of water conservation included the construction of a water sewage system, especially during the processing of coffee to reduce environmental pollution. Coffee primary processing requires a lot of water. Coffee farmers indicated performing home processing using their own pulping machines. Water is the most important ingredient in pulping. Some coffee farmers ensure that there is no washing of coffee alongside water sources such as ponds, rivers, springs, and canals. Additionally, coffee farmers ensure they practice farming away from water sources in order to minimize water pollution caused by agrochemicals used in farming, especially during the rainy season.

The proper use of agrochemicals is another area being observed by some coffee farmers (20.5%) in conserving the environment. This includes the use of recommended application methods, amount, and frequency of using herbicides, pesticides, and insecticides. However, coffee farmers involved in certification schemes, especially organic farming, reported using herbs in pest and disease treatment methods that are environmentally friendly. Other methods for those using agrochemicals included the collection and burning of packaging materials used for agrochemicals that could add poison to the environment and affect biodiversity as well as endanger personal health.

3.5. Factors Affecting the Outcome Variables between Certified and Non-Certified Farmers

Sex of the coffee plot manager, education, market outlet, level of specialization, and membership in organizations were found to significantly affect the outcome variables which are household income and environmental conservation (

p < 0.05) (

Table 6). Sex of the farmer and level of education influenced the total household income generated by the farmer. Male farmers were found to have a greater predicted probability of obtaining higher household incomes than females. This was true for both certified and non-certified coffee farmers. This is due to the fact that women have low access and control over various resources in the study areas which are key contributors to household incomes. Additionally, an increase in the level of education was found to increase the predicted probability of obtaining high household incomes for certified coffee farmers.

The level of specialization and sex of the farmer were found to significantly reduce the predicted probability of being aware of and practicing environmental conservation for certified coffee farmers. Male coffee farmers were found to be less concerned with environmental conservation than female. Likewise, the more specialized coffee farmers were found to be less concerned with environmental conservation practices. However, membership in organizations increased the chance of being aware and practicing environmental conservation for both certified and non-certified coffee farmers. Additionally, membership in various organizations and use of AMCOS as the market outlet increased the predicted probability of obtaining high household incomes for the non-certified coffee farmers.

3.6. The Effect of Certification Decisions on Environmental Conservation and Livelihood Improvement

Coffee farmers who were not in the certification schemes earned higher coffee and total household incomes than certified coffee farmers. The t-test results indicated significant differences in annual incomes earned between the two coffee farmer groups (

p < 0.05). Income earned from coffee production activities by certified coffee farmers was USD 490.91 lower than that of non-certified coffee farmers. Similarly, non-certified coffee farmers had a mean annual household income that was USD 762.06 higher than that earned by their counterpart certified farmers (

Table 7). This implies that there are challenges confronting certified farmers that cause them to fail to gain the anticipated benefits, including increased incomes. The differences are reported to emanate from coffee productivity, farm sizes, and the fact that the price premiums are not paid to certified coffee farmers.

Further analysis on the average treatment effects on the treated (ATT) and the average treatment effects on the untreated (ATU) showed a negative value of ATT for the total household income outcome variable and a positive on the environmental conservation. This suggests that coffee farmers who are not in the certification schemes earned higher household incomes than certified farmers. This means that the findings reject the hypothesis of certification to improve household income, on the one hand. On the other hand, certification improves awareness and practice of environmental conservation among coffee farmers (

Table 8). Certified coffee farmers are better placed in conserving the environment. These findings are in line with Kattel [

38], who found certification, especially group organic certification, enhances environmental sustainability. Therefore, certification leads to improved environmental conservation. This is due to the fact that certification schemes are always accompanied by environmental conservation indicators such as pesticide use, water and energy conservation, and biodiversity. Therefore, smallholder coffee certification contributes more to environmental conservation and other sustainability indicators than increased incomes, especially for developing countries like Tanzania.

3.7. Key Challenges in Coffee Certifications

The study identified challenges in accessing certification schemes for some of the coffee farmers. Farmers indicated that they experienced compliance issues with some of the certification schemes. The terms and conditions spelt out in joining the schemes were difficult to comply with. The level of awareness on the availability of different niche markets and opportunities from certification schemes was not known with certainty by many coffee farmers in the study areas. This can be linked to the inefficiencies in sharing market information within the coffee supply chain.

Many coffee farmers (49.8%) disagreed on whether it was easy to access niche export coffee markets. Few coffee farmers (23.3%) were indifferent and the remaining proportion (26.9%) indicated that they agreed with the statement. The level of agreement on the statements is shown in

Figure 5. The Likert scale responses were such that 1 (20%) was strongly disagree, 2 (40%) was disagree, 3 (60%) was neutral/indifferent, 4 (80%) was agree, and 5 (100%) was strongly agree. Coffee farmers who agreed on a statement are above the neutral/indifferent line (60%) which separates level of agreement and that of disagreement, while coffee farmers who disagreed on a stated statement are indicated below the neutral line (60%). Many of the coffee farmers who disagreed on easiness in accessing the niche markets were in the non-certified group. Non-certified coffee farmers experienced difficulties in accessing the certification services. They lacked information on the availability of certification services and also experienced issues related to compliance. However, even if the certification services were accessible, many coffee farmers (56.6%) from both groups disagreed with the statement of them being easy to obtain.

The prevalence of coffee diseases, such as coffee berry disease (CBD) (

Colletotrichum kahawae), was mentioned as one of the reasons that made some coffee farmers hesitate to obtain organic coffee farming certification. CBD has been affecting coffee farmers for quite a long time. Similarly, the study by Otieno, Alwenge [

39] identified CBD as being one of the key diseases affecting coffee farmers in Tanzania. Some coffee farmers reported non-availability of organic agricultural inputs to support them once they are certified. They indicated that these inputs were readily available in their location, but their commercialization and availability in bulk was a major constraining factor. This affected the ability of farmers in the study areas to comply with organic certification. In fact, some coffee farmers could not realize the price advantage and yield gains expected from joining the certification schemes. The findings of our study indicate that some farmers sold their organic coffee at relatively similar prices as those offered by farmers who were not certified, hence failing to benefit from price premiums. Generally, certified coffee farmers sold their coffee at 1.1 USD/Kg of parchment while the non-certified farmers sold at 1.4 USD/Kg. The difference is attributed to the associated transaction costs in both groups and buyers’ differences. Transmission of price premiums to coffee farmers is a challenge in many countries. The study by Rich, PG [

40] in India found the premiums to be small. Similarly, the study by Minten, Dereje [

21] in Ethiopia also found the premiums to be hardly transmitted to farmers. This indicates that the price advantages are captured by other actors along the coffee supply chain. The key informants’ results from our study revealed the existence of quality-related issues and overregulation of the coffee marketing system, which in turn hindered coffee farmers from benefiting from price advantages. However, many coffee farmers (60.6%) reported that their coffee met international standards in terms of quality. More certified coffee farmers indicated that they had better quality coffee than the non-certified coffee farmers.

The state of government regulation in the sector was mentioned by many coffee farmers as challenging. Our results show that 54.8% of the coffee farmers agreed with the assertion that the existing government regulations and restrictions constitute the major obstacle to coffee trade. The level of agreement was higher for non-certified coffee farmers than the certified coffee farmers. Farmers indicated complications associated with direct coffee exports. The involvement of private buyers in buying coffee directly from farmers has also been limited by the new government regulations that require all coffee to go through the auction system.

The other challenge identified was coffee productivity. Some farmers (25.5%) indicated that they faced productivity challenges regardless of the certification scheme. Organic certified farmers reported obtaining lower productivity by 34.7 kg/ha compared to their counterparts. This is because the organic fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides are cumbersome to obtain. The low productivity leads to increased production costs affecting the whole coffee production efficiency. The price premiums that are expected to offset the productivity gap are hard to obtain.

Additionally, 56.8% of the coffee farmers surveyed indicated that certification was not cost effective. The costs vary, ranging from 150–500 USD/ha and an annual auditing fee of USD 1000–5000. The high cost of certification and auditing makes coffee farmers lose their sovereignty in accessing the price premiums. This is because the certification and auditing costs are thus paid by traders or exporting companies, for which reciprocating the benefits to the coffee farmers seems not to be working for the coffee farmers. However, certification is increasingly viewed as necessary to be able to access export coffee markets.

4. Conclusions

Certification is increasingly perceived as necessary for accessing export markets among coffee farmers in developing countries. Coffee farmers need to join the certification schemes to be capable of accessing niche export markets and to gain social, economic, and environmental benefits associated with certification. Certification-enhancing policies will spur the production of sustainably grown coffee, social equity, and overall sustainability within the coffee supply chain.

This study faced two main limitations which were dealt with during data collection, cleaning, and analysis. These limitations were respondents’ recall bias and the use of gross income rather than net income to measure livelihood improvement. Many of the respondents do not keep records or inventories of costs, purchases, and revenues. This affects the reporting of the revenues and cost streams. However, the study has well highlighted the status, constraints, key drivers, and impact of the coffee certifications in Tanzania as one of the coffee producers in developing countries. The level of coffee certification is still low, requiring interventions that will address the key constraints of certification. The key constraints include the low level of awareness and accessibility, the prevalence of coffee diseases, failure in realizing price advantage, and certification not being cost-effective for coffee farmers. The study also found that the decision of the coffee farmer to join a certification scheme was influenced by factors including economies of scale, experience, and participation in collective actions. Additionally, the study rejects the hypothesis of certification to improve household incomes. Nevertheless, certification improved awareness and practice of environmental conservation among coffee farmers.

It is thus important for private and public institutions to embark on awareness creation and make certification services accessible and cost effective to coffee farmers as well as enhancing access to niche export markets. Easing transmission of price premiums to coffee farmers will increase the supply of sustainably grown coffee, improve coffee farmers’ livelihoods, and attain environmental sustainability goals within the coffee supply chain.