De-Escalation of Antiplatelet Treatment in Patients with Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Review of the Current Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

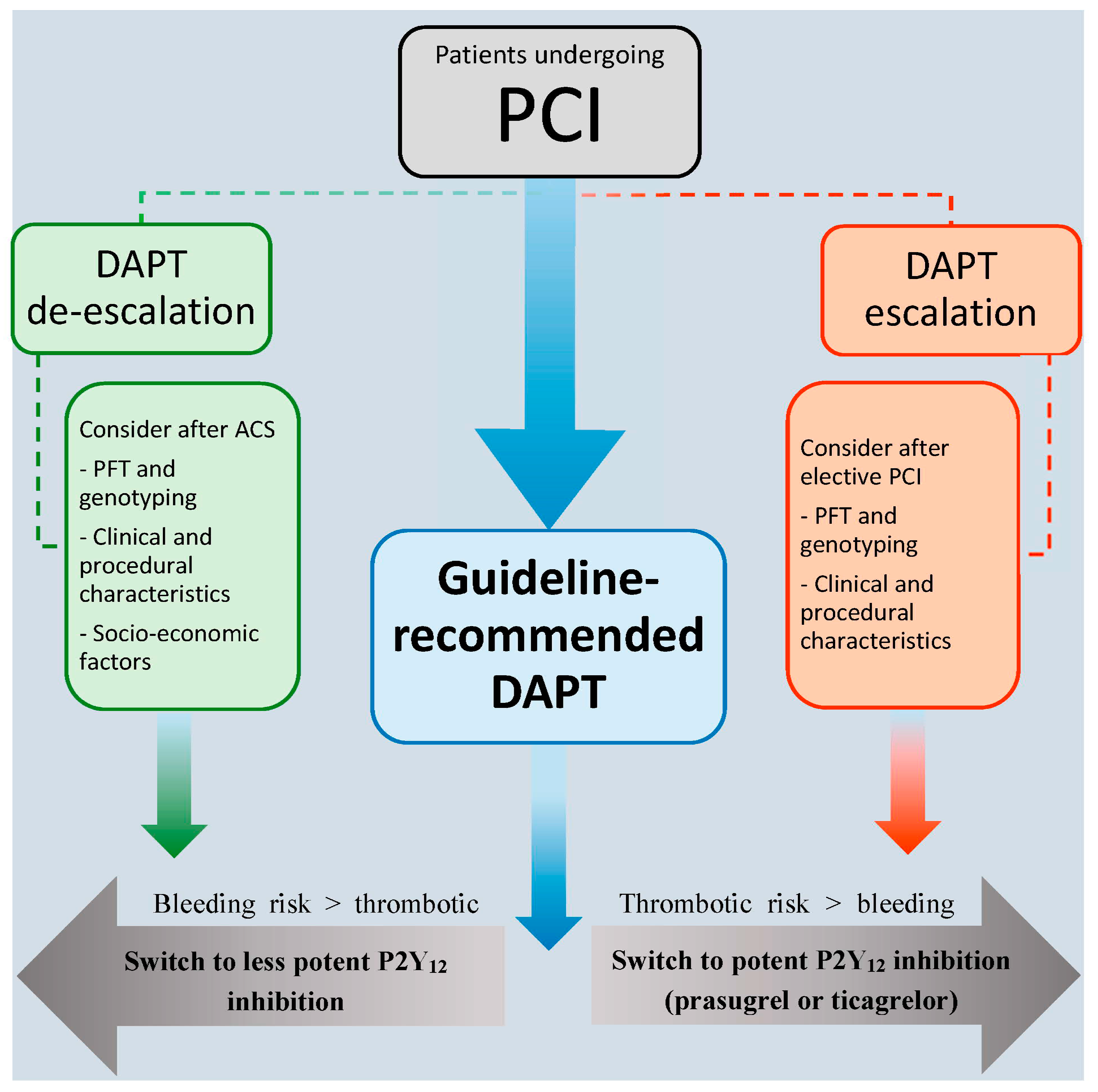

2. De-Escalation of Antithrombotic Therapy

3. Unguided De-Escalation

4. Platelet Function Testing-Guided De-Escalation

5. Genotype-Guided De-Escalation

6. Summary

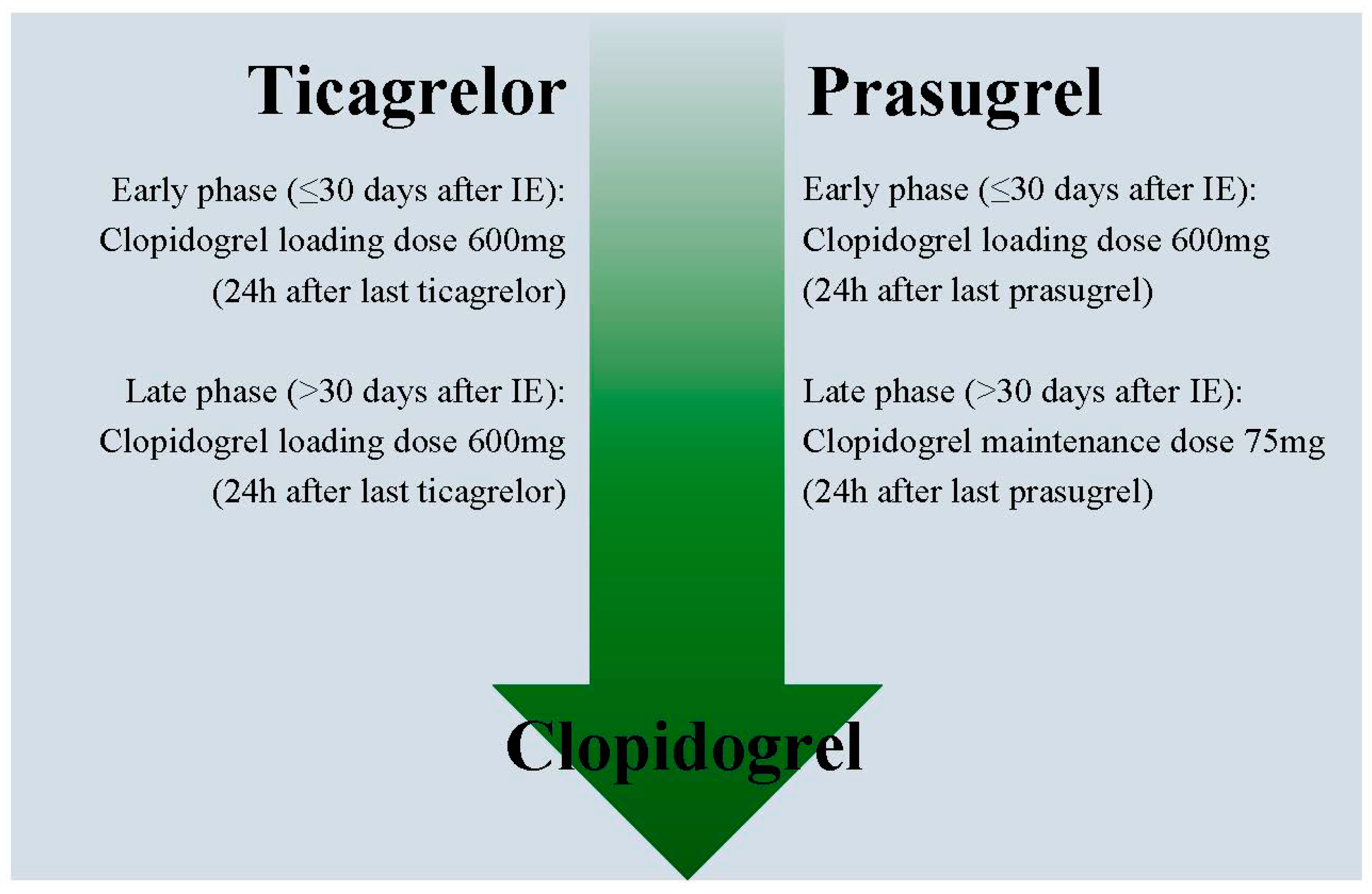

7. How to De-Escalate Antiplatelet Therapy

8. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ibanez, B.; James, S.; Agewall, S.; Antunes, M.J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Bueno, H.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Crea, F.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Halvorsen, S.; et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 119–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Levine, G.N.; Bates, E.R.; Bittl, J.A.; Brindis, R.G.; Fihn, S.D.; Fleisher, L.A.; Granger, C.B.; Lange, R.A.; Mack, M.J.; Mauri, L.; et al. 2016 ACC/AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 1082–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallentin, L.; Becker, R.C.; Budaj, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Emanuelsson, H.; Held, C.; Horrow, J.; Husted, S.; James, S.; Katus, H.; et al. Ticagrelor versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Braunwald, E.; McCabe, C.H.; Montalescot, G.; Ruzyllo, W.; Gottlieb, S.; Neumann, F.-J.; Ardissino, D.; De Servi, S.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Prasugrel versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2001–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Werkum, J.; Heestermans, A.; Deneer, V.; Hackeng, C.; Ten Berg, J. Clopidogrel resistance: Fact and fiction. Futur. Cardiol. 2006, 2, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breet, N.J.; Van Werkum, J.W.; Bouman, H.J.; Kelder, J.C.; Ruven, H.J.T.; Bal, E.T.; Deneer, V.H.; Harmsze, A.M.; Van Der Heyden, J.A.S.; Rensing, B.J.W.M.; et al. Comparison of Platelet Function Tests in Predicting Clinical Outcome in Patients Undergoing Coronary Stent Implantation. JAMA 2010, 303, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassens, D.M.; Berg, J.M.T. Genotype-guided treatment of oral P2Y12 inhibitors: Where do we stand? Pharmacogenomics 2020, 21, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harmsze, A.M.; Van Werkum, J.W.; Ten Berg, J.M.; Zwart, B.; Bouman, H.J.; Breet, N.J.; van ‘t Hof, A.W.; Ruven, H.J.; Hackeng, C.M.; Klungel, O.H.; et al. CYP2C19*2 and CYP2C9*3 alleles are associated with stent thrombosis: A case-control study. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 3046–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Angiolillo, D.J.; Fernández-Ortiz, A.; Bernardo, E.; Alfonso, F.; Macaya, C.; Bass, T.A.; Costa, M.A. Variability in Individual Responsiveness to Clopidogrel. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antman, E.M.; Wiviott, S.D.; Murphy, S.A.; Voitk, J.; Hasin, Y.; Widimský, P.; Chandna, H.; Macias, W.; McCabe, C.H.; Braunwald, E. Early and Late Benefits of Prasugrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 51, 2028–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, R.C.; Bassand, J.P.; Budaj, A.; Wojdyla, D.M.; James, S.K.; Cornel, J.H.; French, J.; Held, C.; Horrow, J.; Husted, S.; et al. Bleeding complications with the P2Y12 receptor antagonists clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 2933–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Motovska, Z.; Hlinomaz, O.; Kala, P.; Hromadka, M.; Knot, J.; Varvarovsky, I.; Dusek, J.; Jarkovsky, J.; Miklik, R.; Rokyta, R.; et al. 1-Year Outcomes of Patients Undergoing Primary Angioplasty for Myocardial Infarction Treated with Prasugrel Versus Ticagrelor. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 71, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimbel, M.; Qaderdan, K.; Willemsen, L.; Hermanides, R.; Bergmeijer, T.; De Vrey, E.; Heestermans, T.; Tjon-Joe Gin, M.; Waalewijn, R.; Hofma, S.; et al. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): The randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettler, M.E.; Peterson, E.D.; McCoy, L.A.; Effron, M.B.; Anstrom, K.J.; Henry, T.D.; Baker, B.A.; Messenger, J.C.; Cohen, D.J.; Wang, T.Y.; et al. Switching of adenosine diphosphate receptor inhibitor after hospital discharge among myocardial infarction patients: Insights from the Treatment with Adenosine Diphosphate Receptor Inhibitors: Longitudinal Assessment of Treatment Patterns and Events after Acute Coronary Syndrome (TRANSLATE-ACS) observational study. Am. Hear. J. 2017, 183, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Angiolillo, D.J.; Patti, G.; Chan, K.T.; Han, Y.; Huang, W.-C.; Yakovlev, A.; Paek, D.; Del Aguila, M.; Girotra, S.; Sibbing, D. De-escalation from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in acute coronary syndrome patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2019, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuisset, T.; Deharo, P.; Quilici, J.; Johnson, T.W.; Deffarges, S.; Bassez, C.; Bonnet, G.; Fourcade, L.; Mouret, J.P.; Lambert, M.; et al. Benefit of switching dual antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: The TOPIC (timing of platelet inhibition after acute coronary syndrome) randomized study. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 3070–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sibbing, D.; Aradi, D.; Jacobshagen, C.; Gross, L.; Trenk, D.; Geisler, T.; Orban, M.; Hadamitzky, M.; Merkely, B.; Kiss, R.G.; et al. Guided de-escalation of antiplatelet treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (TROPICAL-ACS): A randomised, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1747–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Claassens, D.M.F.; Vos, G.J.A.; Bergmeijer, T.O.; Hermanides, R.S.; van ‘t Hof, A.W.J.; van der Harst, P.; Barbato, E.; Morisco, C.; Tjon-Joe Gin, R.M.; Asselbergs, F.W.; et al. AGenotype-guided strategy for oral P2Y12 inhibitors in primary PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1621–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deharo, P.; Quilici, J.; Camoin-Jau, L.; Johnson, T.W.; Bassez, C.; Bonnet, G.; Fernandez, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Suchon, P.; Verdier, V.; et al. Benefit of Switching Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Acute Coronary Syndrome According to On-Treatment Platelet Reactivity. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, 2560–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Kang, J.; Hwang, D.; Han, J.-K.; Yang, H.-M.; Kang, H.-J.; Koo, B.-K.; Rhew, J.Y.; Chun, K.-J.; Lim, Y.-H.; et al. Prasugrel-based de-escalation of dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS): An open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority randomised trial. Lancet 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Tarantini, G.; Saia, F.; Parodi, G.; Varbella, F.; Marchese, A.; De Servi, S.; Berti, S.; Bolognese, L. Incidence and Outcome of Switching of Oral Platelet P2Y12 Receptor Inhibitors in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The SCOPE Registry. EuroIntervention 2017, 13, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, P.W.A.; Bergmeijer, T.O.; Vos, G.-J.A.; Kelder, J.C.; Qaderdan, K.; Godschalk, T.C.; Breet, N.J.; Deneer, V.H.M.; Hackeng, C.M.; Ten Berg, J.M. Tailored P2Y12 inhibitor treatment in patients undergoing non-urgent PCI—The POPular Risk Score study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 75, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M.J.; Berger, P.B.; Teirstein, P.S.; Tanguay, J.-F.; Angiolillo, D.J.; Spriggs, D.; Puri, S.; Robbins, M.; Garratt, K.N.; Bertrand, O.F.; et al. Standard- vs High-Dose Clopidogrel Based on Platelet Function Testing After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JAMA 2011, 305, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collet, J.-P.; Cuisset, T.; Rangé, G.; Cayla, G.; Elhadad, S.; Pouillot, C.; Henry, P.; Motreff, P.; Carrie, D.; Boueri, Z.; et al. Bedside Monitoring to Adjust Antiplatelet Therapy for Coronary Stenting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2100–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sibbing, D.; Gross, L.; Trenk, D.; Jacobshagen, C.; Geisler, T.; Hadamitzky, M.; Merkely, B.; Kiss, R.G.; Komócsi, A.; Parma, R.; et al. Age and outcomes following guided de-escalation of antiplatelet treatment in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: Results from the randomized TROPICAL-ACS trial. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 2749–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsen, P.D.; Holley, A.S.; Sasse, A.; Al-Sinan, A.; Fairley, S.; Harding, S.A. Comparison of Multiplatelet and VerifyNow platelet function tests in predicting clinical outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Thromb. Res. 2017, 152, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.L.; Farkouh, M.E.; So, D.; Lennon, R.; Geller, N.; Mathew, V.; Bell, M.; Bae, J.; Jeong, M.H.; Chavez, I.; et al. Effect of Genotype-Guided Oral P2Y12 Inhibitor Selection vs Conventional Clopidogrel Therapy on Ischemic Outcomes After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The TAILOR-PCI Randomized Clinical trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, L.H.; Lee, C.R.; Beitelshees, A.L.; Cooper-DeHoff, R.M.; Duarte, J.D.; Voora, D.; Kimmel, E.; McDonough, C.W.; Gong, Y.; Dave, C.V.; et al. Multi-site investigation of outcomes with implementation of CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 11, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, J.P.; Thiele, H.; Barbato, E.; Barthélémy, O.; Bauersachs, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Dendale, P.; Dorobantu, M.; Edvardsen, T.; Folliguet, T.; et al. OUP accepted manuscript. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 00, 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibbing, D.; Aradi, D.; Alexopoulos, D.; Berg, J.T.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bonello, L.; Collet, J.-P.; Cuisset, T.; Franchi, F.; Gross, L.; et al. Updated Expert Consensus Statement on Platelet Function and Genetic Testing for Guiding P2Y12 Receptor Inhibitor Treatment in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, 1521–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiolillo, D.J.; Rollini, F.; Storey, R.F.; Bhatt, D.L.; James, S.; Schneider, D.J.; Sibbing, D.; So, D.Y.; Trenk, D.; Alexopoulos, D.; et al. International Expert Consensus on Switching Platelet P2Y12 Receptor—Inhibiting Therapies. Circulation 2017, 136, 1955–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claassens, D.M.F.; Tavenier, A.H.; Hermanides, R.S.; Vos, G.J.A.; Hinrichs, D.L.; Bergmeijer, T.O.; van ‘t Hof, A.W.J.; Deneer, V.H.M.; Ten Berg, J.M. Reloading when switching from ticagegrelor or prasugrel to clopidogrel within 7 days after STEMI. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Table Header | TOPIC | TROPICAL-ACS | POPular Genetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Size | n = 646 | n = 2610 | n = 2488 |

| Population | ACS + PCI (40% STEMI) | (N)STEMI + PCI (55% STEMI) | STEMI + primary PCI (100% STEMI) |

| Timing of De-Escalation | 1 Month After ACS | 7 Days After Discharge | 1–3 Days After Primary PCI |

| Method of De-Escalation | Unguided | PFT-Guided | Genotype-Guided |

| Study Design | Single-Center, Randomized, Open-Label Trial of Unguided De-Escalation Vs. Standard Treatment | Randomized, Open-Label, Non-Inferiority Trial Of PFT-Guided De-Escalation Vs. Standard Treatment | Randomized, Open-Label, Non-Inferiority Trial of Genotype-Guided De-Escalation Vs. Standard Treatment |

| Control Arm | Ticagrelor/Prasugrel for 12 Months | Prasugrel for 12 Months | Ticagrelor/Prasugrel for 12 Months |

| Experimental Arm | 1 Month of Ticagrelor/Prasugrel Followed By 11 Months of Clopidogrel | PFT-Guided De-Escalation With 1 Week Prasugrel Followed By 1 Week Clopidogrel, Then Depending on PFT Results Clopidogrel Or Prasugrel From Day 14 To 12 Months | CYP2C19 Genotyping Immediately After Primary PCI. Non-Carriers of loF Alleles Switched to Clopidogrel As Soon As Possible, Carriers Continued Ticagrelor/Prasugrel for 12 Months |

| Primary Endpoint | 1-Yr Incidence of Cardiovascular Death, Unplanned Hospitalization Leading to Urgent Coronary Revascularization, Stroke or BARC ≥ 2 Bleeding | 1-Yr Incidence of Cardiovascular Death, Myocardial Infarction, Stroke or BARC ≥ 2 Bleeding | 1-Yr Incidence of All-Cause Death, Myocardial Infarction, Definite Stent Thrombosis, Stroke or PLATO Major Bleeding |

| Key Safety Endpoint | BARC ≥2 Bleeding | BARC ≥2 Bleeding | PLATO Major and Minor Bleeding |

| Key Findings | Primary Net Clinical Benefit Endpoint (13.4% In De-Escalation Vs. 26.3% In Control Group; P < 0.01; HR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.34–0.68 Thrombotic Event Rates Of 9.3% In De-Escalation Vs. 11.5% In Control Group; P = 0.36 Bleeding Event Rates Of 4.0% In De-Escalation Vs. 14.9% In Control Group; HR 0.30, 95% CI: 0.18–0.50; P < 0.01 | Primary Net Clinical Benefit Endpoint (7.3% In De-Escalation Vs. 9.0% In Control Group; Pnoninf <0.001; HR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.62–1.06 Thrombotic Event Rates Of 2.5% In De-Escalation Vs. 3.2% In Control Group; HR 0.77, 95% CI: 0.48–1.21; Pnoninf = 0.01 Bleeding Event Rates Of 4.9% In De-Escalation Vs. 6.1% In Control Group; HR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.59–1.13; P = 0.23 | Primary Net Clinical Benefit Endpoint (5.1% In De-Escalation Vs. 5.9% In Control Group; Pnoninf <0.001; HR: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.62–1.21 Thrombotic Event Rates Of 2.7% In De-Escalation Vs. 3.3% In Control Group; HR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.53–1.31 Bleeding Event Rates Of 9.8% In De-Escalation Vs. 12.5% In Control Group; HR 0.78, 95% CI: 0.61–0.98; P = 0.04 |

| Funding | Investigator Initiated Trial. Funded by Hôpitaux De La Timone | Investigator Initiated Trial Funded by Roche Diagnostics. Eli Lilly & Daiichi Sankyo Company Supported Prasugrel Purchase and Drug Delivery | Investigator Initiated Trial. Funded by Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Spartan Bioscience Provided Genotyping Equipment for Free |

| Prior Major Bleeding |

|---|

| Anemia |

| Clinically Significant Bleeding on Potent P2Y12 Inhibitors |

| High Bleeding Risk Defined by Bleeding Risk Scores |

| Socio-Economic Factors Favoring the Lower Costs of Clopidogrel |

| Side Effects on Prasugrel And Ticagrelor, Especially Dyspnea on Ticagrelor |

| Need for Triple Treatment Due to New Onset Atrial Fibrillation or Left Ventricular Thrombus After Myocardial Infarction |

| Table Header | Platelet Function Testing | Genotyping |

|---|---|---|

| Availability of Different Assays | Yes | Yes |

| Availability of Point-Of-Care Systems | Yes | Yes |

| Inter-Assay Variability | Yes | No |

| Variability of Results Over Time | Yes | No |

| Association with Thrombotic Events | Yes | Yes |

| Association with Bleeding Events | Yes | Yes |

| Availability of Clinical Trial Data on Guided Therapy | Yes | Yes |

| Feasibility in Clinical Practice | Yes | Yes |

| Results Influenced by Extra Patient Factors | Yes | No |

| Direct Measure of Response to Therapy | Yes | No |

| Assessment of Influence of Both Genetic and Non-Genetic Factors on Platelet Function | Yes | No |

| Need to Be Performed While on Treatment | Yes | No |

| Modified and Adapted with Permission from Sibbing Et Al. [30] | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Claassens, D.M.; Sibbing, D. De-Escalation of Antiplatelet Treatment in Patients with Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Review of the Current Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2983. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092983

Claassens DM, Sibbing D. De-Escalation of Antiplatelet Treatment in Patients with Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Review of the Current Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(9):2983. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092983

Chicago/Turabian StyleClaassens, Daniel MF, and Dirk Sibbing. 2020. "De-Escalation of Antiplatelet Treatment in Patients with Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Review of the Current Literature" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 9: 2983. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092983

APA StyleClaassens, D. M., & Sibbing, D. (2020). De-Escalation of Antiplatelet Treatment in Patients with Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Review of the Current Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(9), 2983. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092983