1. Introduction

Skin cancer is categorized as non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and melanoma [

1]. NMSC (excluding basal-cell carcinomas, BCCs) was the 5th most common form of cancer worldwide in 2018, involving over 1 million of new diagnoses and 65,000 death, while melanoma was the 21th with nearly 300,000 new cases and 60,000 death [

1]. In pigmented skin lesions (PSLs), an extreme progression of melanocytes, which are pigment-producing cells in the basal layer of the epidermis, is found. PSLs can be classified as benign or malignant [

2]. The most common NMSC are BCC and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). BCC is associated with low mortality (and usually not included in general cancer statistics) due to has low metastatic potential. However, patients with SCC have a high risk of developing subsequent nodal metastases [

3]. On the other hand, the most dangerous type of skin cancer is malignant melanoma, which lead to the death of patients in higher proportion due to the late detection of pathology and its higher risk to produce systemic metastases [

2]. The process to diagnose skin cancer is accomplished by a dermatologist who perform a preliminary diagnosis by visually examining the PSL following the ABCDE (Asymmetry of the mole, Border irregularity, Color uniformity, Diameter and Evolving size, shape or color) rule [

4]. After this examination, a biopsy is performed if the dermatologist suspects that the lesion is malignant. Then, a pathological analysis of the sample is carried out to assess the definitive diagnosis. There are several tools based on dermoscopic images and algorithms that implement the ABCD rule (without taking into account the evolving characteristics) to assist dermatologist in their clinical routine practice for PSL evaluation and classification [

5,

6]. Nevertheless, the current methodologies are not accurate enough, giving as a result several false positives and negatives. To avoid unnecessary surgical procedures, because of the uncertainty in the current diagnoses, new methods to improve skin cancer diagnosis must be investigated.

In recent years, a non-invasive, non-ionizing and label-free imaging modality is arising in the medical field: hyperspectral imaging (HSI). This imaging modality can combine digital imaging with spectroscopy methods, providing increased spectral properties of a captured scene within and beyond the visual range of the electromagnetic spectrum [

7,

8]. In a hyperspectral (HS) image, each pixel contains the so-called spectral signature of the material/substance located in its corresponding spatial coordinates. It has been demonstrated that quantitative information of tissue physiology can be extracted through the spectral signature analysis [

9]. The fundamentals of this technology and the instruments developed for capturing such type of data for in-vivo applications in the medical field have been widely studied [

10]. However, there are few research dealing with the use of HSI for in-vivo skin cancer detection as presented in the review performed by Johansen et al. [

11].

In the study carried out by Tomatis et al. authors had the goal of diagnosing melanoma lesions using a classifier based on a multilayer perceptron neural network model [

12]. They employed a multispectral (MS) acquisition system (SpectroShade

®) able to capture MS images of 15 spectral bands between 483 and 950 nm. With such system they generated an in-vivo skin PSL database of 1391 MS images (including 184 melanomas) from 1278 patients. The reported sensitivity and specificity results in the test set (including 306 non-melanoma and 41 melanoma lesions) were of 80.5% and 77.1%, respectively. Other commercial MS systems have been developed to assist in the detection of melanoma, such as SIAscope/SIAscopy [

13] or MelaFind [

14,

15,

16]. First, SIAscope/SIAscopy was capable to capture 8 bands in the 400–1000 nm spectral range, obtaining a sensitivity of 82.7% and a specificity of 80.1% for melanoma identification in a dataset composed by 52 melanomas and 296 non-melanoma PSLs [

13]. Second, MelaFind is able to acquire MS images composed by 10 bands in the spectral rage comprised between 430 and 950 nm, being used in several research studies. In [

14], Elbaum et al. reported sensitivity and specificity values of 100% and 84%, respectively, under a leave-one-out cross-validation procedure using a database composed by 63 melanomas and 183 melanocytic nevus. In [

15], Monheit et al. achieved a 98.4% of sensitivity and 9.9% of specificity in a prospective multicenter study where a dataset conformed by 127 melanomas and 1505 non-melanoma lesions was generated. In [

16], Fink et al. performed an observational study where 360 PSLs (3 melanomas and 357 excised and non-excised non-melanoma lesions) were captured, achieving a sensitivity and specificity values of 100% and 68.5%, respectively. Finally, Song et al. performed a paired comparison between MelaFind and a reflectance confocal microscopy system to differentiate between melanoma and non-melanoma in a small sample size database composed by 4 melanomas and 51 non-melanoma lesions [

17]. The results obtained showed a superiority of the confocal microscopy system (sensitivity of 85.7% and specificity of 71.4%) respect to the MelaFind system (sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 25%).

Other research works developed customized classification frameworks to automatically differentiate between melanoma and non-melanoma lesions by using an HSI system based on a spatial scanning HS camera (ImSpector V8E, Specim, Oulu, Finland) [

18,

19,

20]. These studies employed HS images composed by 124 bands in the spectral range of 380–780 nm, obtaining, in the most recent clinical trial, sensitivity and specificity values of 96% and 87%, respectively, with a database composed by 24 melanomas and 110 non-melanoma lesions [

20].

Regarding to the discrimination between malignant and beings PSLs, the study of Stamnes et al. employed a MS acquisition system that captured 10 bands in the 365–1000 nm spectral range [

21]. They reported sensitivity and specificity results of 97% in both metrics using a test set conformed by 35 malignant and 120 benign PSLs.

Despite these state-of-the-art works and commercial systems available for assisting in the skin cancer diagnosis using mainly MS imaging for melanoma and non-melanoma discrimination, there are still room for improvements and investigations using HSI for malignant and benign PSL discrimination, providing higher number of spectral bands in larger spectral ranges.

In this sense, the main goal of this research is the development of a classification framework based on HS image segmentation and supervised classification by employing a customized dermatologic HSI system (developed by this research group) able to capture real-time HS data of in-vivo PSLs composed by 125 bands in the 450–950 nm spectral range. This preliminary study aims to demonstrate, as a proof-of-concept, the potential use of HSI technology to assist dermatologists in the discrimination of benign and malignant PSLs (including both NMSC and melanoma lesions) during clinical routine practice using a real-time and non-invasive hand-held device. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work focused in using snapshot HS cameras within the visual and near-infrared (VNIR) range to segment and classify among benign and malignant PSLs using only spectral information.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hyperspectral Dermatologic Acquisition System

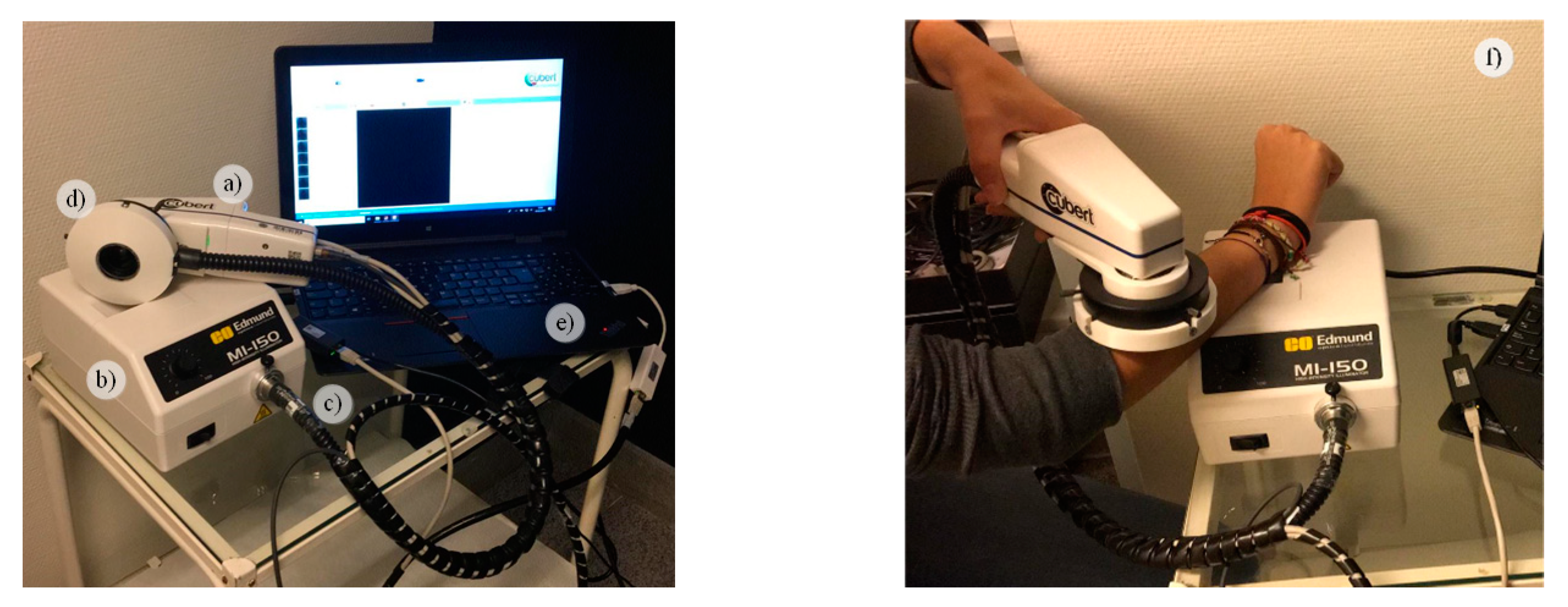

The HS dermatologic acquisition system used in this work for the assistance in the diagnosis of PSLs is a custom development described in detail in [

22]. The system is composed by a snapshot HS camera (Cubert UHD 185, Cubert GmbH, Ulm, Germany) capable of capturing HS data in the visual and near-infrared (VNIR) spectral range from 450 to 950 nm, having a spectral resolution of 8 nm (125 spectral bands) and a spatial resolution of 50 × 50 pixels (pixel size of 240 × 240 µm) (

Figure 1a). This camera has coupled a Cinegon 1.9/10 (Schneider Optics Inc., Hauppauge, NY, USA) lens with a F-number of 1.9 and a focal length of 10.4 nm. The acquisition system employs a 150 W QTH-based (Quartz-Tungsten Halogen) illumination system (Dolan-Jenner, Boxborough, MA, USA) (

Figure 1b) coupled to a fiber optic ring light guide to obtain cold light emission in the skin surface, avoiding the high temperatures produced by the halogen lamp (

Figure 1c). The illumination system is attached to the HS camera through a 3D printed customized dermoscopic contact structure where the skin contact part is a dermoscopic lens with the same refraction index as the human skin (

Figure 1d). The HS dermatologic system can capture HS images, with an effective area of 12 × 12 mm, with an acquisition time of ~250 ms. This system is connected to a laptop where the acquisition software is executed (

Figure 1e).

Figure 1f shows and example of the use of the developed HS dermatologic acquisition system during a clinical data acquisition campaign at the University Hospital Doctor Negrin of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain).

2.2. Study Design and HS Dataset Description

The HS dermatologic acquisition system was employed to obtain an HS in-vivo human PSL database to evaluate the efficiency of HS images to discriminate between benign and malignant lesions. The data acquisition campaign was performed from March 2018 to June 2019. Several types of PSLs from different parts of the body were captured from 116 subjects in two different hospitals, the Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Doctor Negrín and Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular - Materno Infantil (Spain). The study protocol and consent procedures were approved by the Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica-Comité de Ética en la Investigación (CEIC/CEI) from both hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

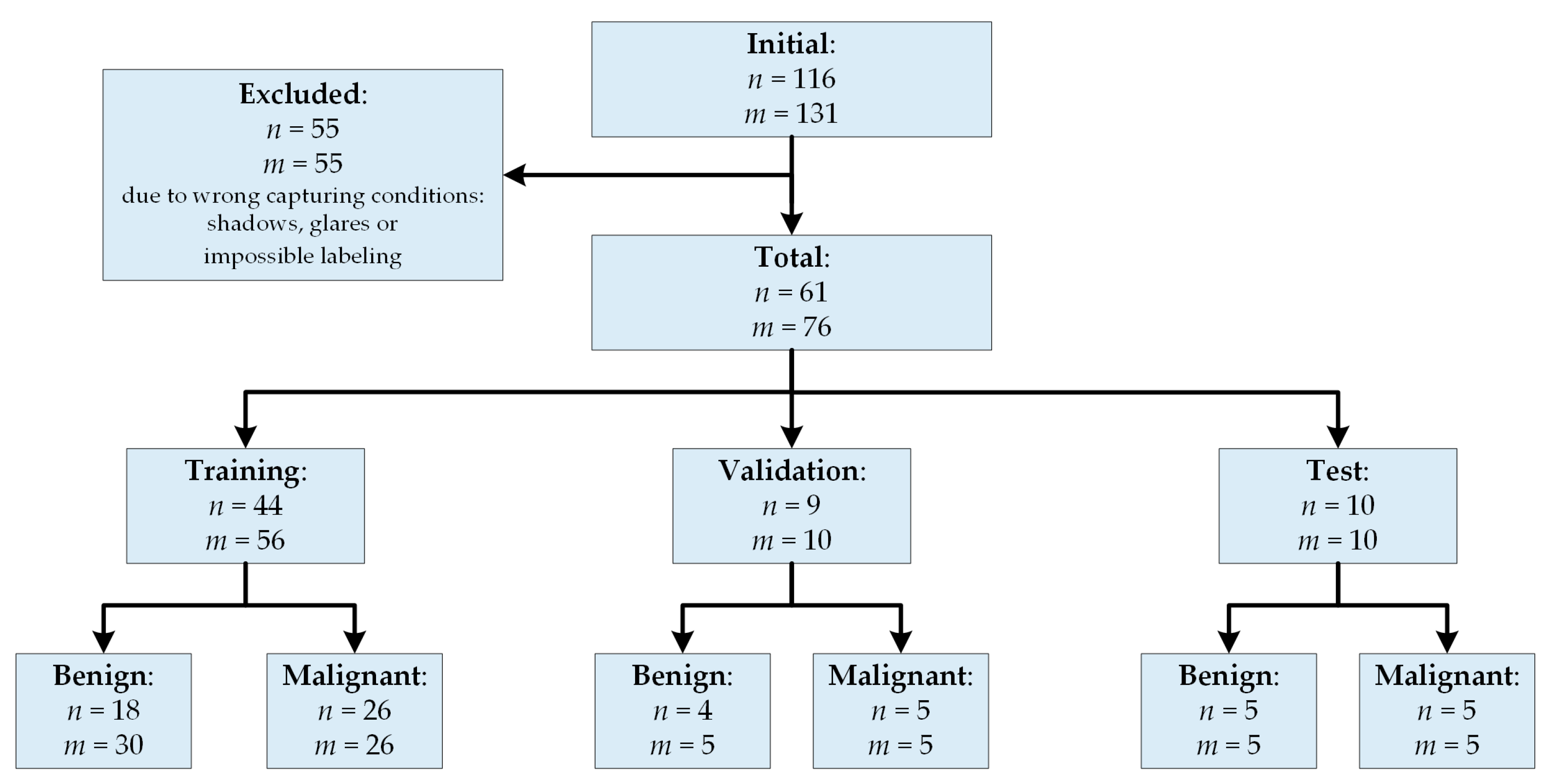

After a preliminary analysis of the captured data, 55 subjects/images were removed from the database due to the PSLs were located in areas extremely difficult to be captured (e.g., shoulders, nose, chin, and other parts of the face) and, hence, the HS images were not recorded in optimal conditions. The dermoscopic lens had no complete contact with the skin surface, producing shadows or glares in the images and, consequently, it was impossible to perform reliable image calibration or PSL labeling on captured HS images. The final database was composed by 76 images from 61 subjects as shown in

Figure 2, where it is also included the training, validation and test set distribution of this preliminary study.

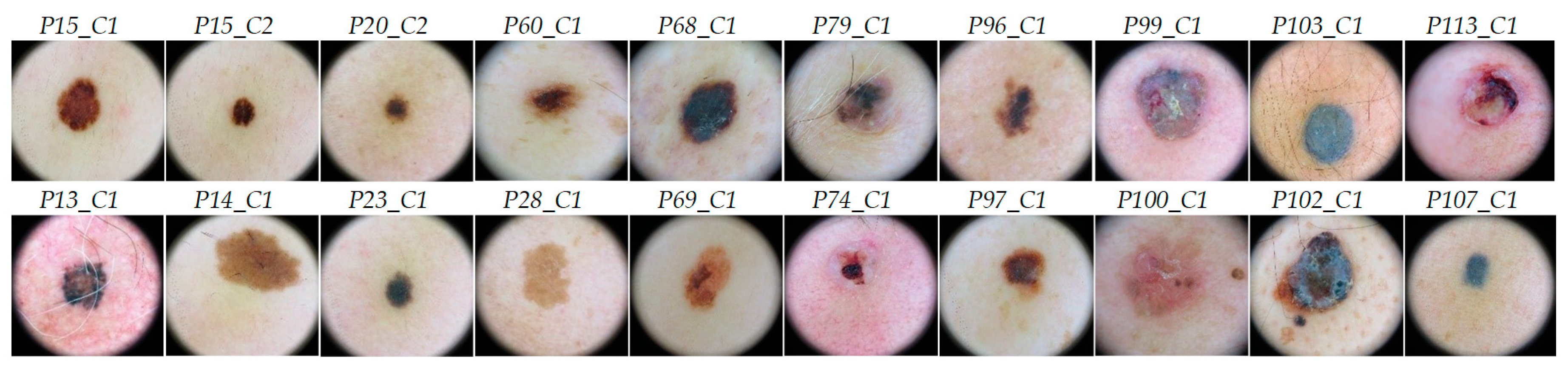

In addition to the HS image, a standard digital dermoscopic camera (3Gen Dermlite Dermatoscope, 3Gen Inc., San Juan Capistrano, CA, USA) was employed to capture conventional RGB images of 3000 × 4000 pixels (pixel size of 6.6 × 6.6 µm) of the same PSL for dermatologist evaluation. Suspected malignant lesions were diagnosed through histological assessment.

2.2.1. HS Labeled Dataset

A labeled dataset was created employing the HS images by assigning to certain pixels the diagnostic class of the PSL obtained from the dermatologist/pathologist assessment. This assignation was performed by using a semi-automatic labeling tool based on the SAM (Spectral Angle Mapper) algorithm. This algorithm determines the spectral similarity between two spectral signatures, where lower spectral angle values indicate higher similarity among both spectral signatures [

23]. The semi-automatic labeling tool allows labeling the most similar pixels in the image with respect to a reference pixel, which was manually selected and identified to belong to a certain class. Only pixels with high confidence to belong to a class were labeled. This tool has been already employed to label HS images in-vivo brain surface for brain tumor classification [

24]. After performing the labeling of the entire database, a total of 15,961 pixels were used for the classification experiments employing machine learning algorithms. The data were labeled in two different classes:

Benign and

Malignant. Concretely, the labeled dataset was composed by 61 patients, but two of them have different lesions captured where one lesion belongs to the benign class and the other lesion belong to the malignant class.

Table 1 shows the number of patients, images and labeled pixels per class.

Figure 3 shows some RGB dermoscopic images obtained by using the digital dermoscopic camera. The HS images corresponding to these image IDs were employed as validation and test sets in the experimental setup.

2.2.2. HS labeled Data Partition

The HS labeled dataset of PSL spectral signatures was employed to train, validate and test the developed classification algorithms. The validation process was performed using a patient stratified assignment where the labeled data were divided into three independent sets:

test,

validation and

training. The test set was composed by labeled data from 10 images from 10 patients with 2472 pixels. The validation set was formed by labeled data from 10 images from 9 patients, having 1931 pixels and, the training set was composed by the remaining labeled data of 56 images from 44 patients, formed by 11,558 pixels.

Table S1 of the supplementary material shows the details of the dataset. Hence, in this dataset different patients were used for training, validation and test.

2.3. HS Dermatologic Data Pre-Processing

The HS data were pre-processed to homogenize the spectral signatures among the different patients and data campaigns. Three main steps form the pre-processing chain: radiometric calibration, noise filtering and normalization.

First, a radiometric calibration was performed to the raw HS image (

RI) employing a white reference image (

WI), captured from a white reference tile able to reflect the 99% of the incident light, and a dark reference image (

DI), recorded by having the light turned off and the camera shutter closed.

WI and

DI were acquired before the PSL data acquisition and in the same illumination conditions. The calibrated image (

CI) was obtained following Equation (1).

Second, in order to reduce the spectral noise found in the spectral signatures, the first 4 bands and the last 5 bands were removed due to the HS sensor low response in such bands. Moreover, the HS data was filtered using a smooth filter for reducing the spectral noise in the remaining spectral bands. The final spectral signature was formed by 116 bands. In the final step, a normalization was applied to each spectral signature to range the data between 0 and 1 with the goal of homogenizing its amplitude, thus avoiding the subsequent processing methods to be affected by the amplitude differences caused by non-uniform illumination conditions. In this sense, only the shape of the spectral signature will be considered.

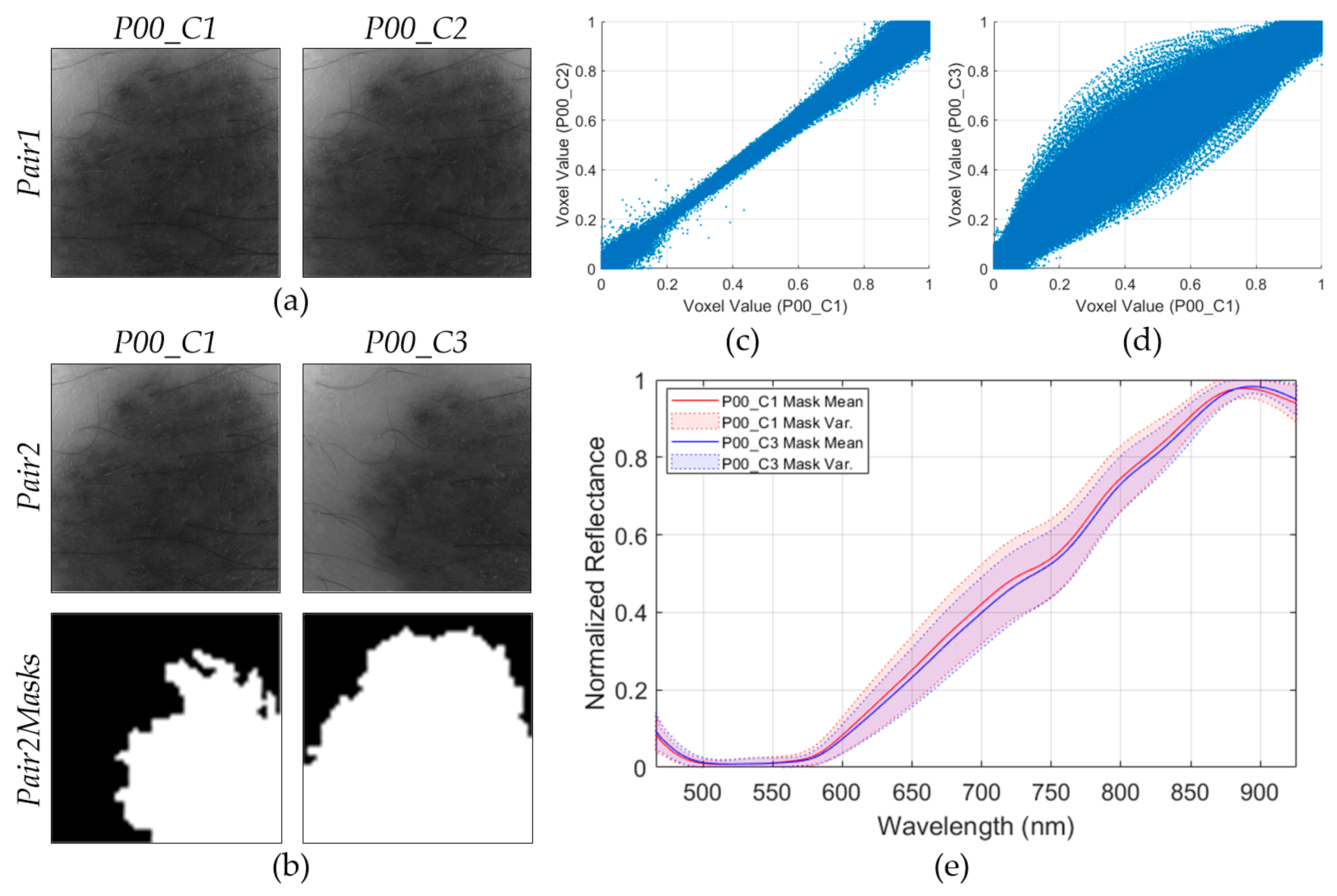

In order to assess the repeatability of the HS dermatologic system, two consecutive HS images of the same lesion in the same exact location (P00_C1 and P00_C2 in

Figure 4a), called Pair1, were employed. Moreover, another pair of images (Pair2) of the same lesion but captured at different spatial positions (P00_C1 and P00_C3 in

Figure 4b) was employed. In order to segment the PSL pixels of the Pair2 images, a binary mask was created for each image, as can be seen in the last row of

Figure 4b, where the white pixels in the Pair2Masks represent the selected PSL pixels.

The main goal of this analysis is the evaluation of the possible systematic errors that can be found in the acquisition system, and also to verify the spectra repeatability when images of the same scene are obtained with subtle different conditions. To perform the repeatability analysis, three experiments were proposed: repeatability of Pair1, repeatability of Pair2, and spectral mean and variance analysis of the Pair2 PSL pixels using the Pair2Masks.

The first experiment evaluates the repeatability of Pair1, where two consecutive HS images of the same lesion (P00_C1 and P00_C2) were captured in the same exact position. To analyze the differences between these images, a scatterplot was employed

Figure 4c), where the voxel values of each HS image of Pair1 are represented (290,000 voxel pairs). The voxel value represents the reflectance of the light in a certain pixel of the HS image at a certain wavelength. Ideally, the scatterplot should be a straight line, which indicates that each voxel pairs encloses the same exact information. As it can be seen, when two consecutive images are compared, the scatterplot is similar to the ideal situation.

In the second experiment, the scatterplot of the HS images of Pair2 (same lesion but different spatial positions) was generated (

Figure 4d). In this case, the scatterplot does not show a straight line, but several voxel pairs have the same information because it is the same injury. For this reason, a third experiment based on a visual comparison of the spectral signatures of the PSL pixels of Pair2 was performed. The PSL pixels were segmented using the Pair2Masks, and the mean and variances of the preprocessed spectral signatures of such pixels were represented in

Figure 4e. As it can be seen, the mean and variances of both images are quite similar, suggesting that the HS dermatologic system is reliable even when capturing data from the same lesion but in different conditions.

Additionally, the absolute relative difference percentage (RD) was obtained for the first and second experiment using Pair1 and Pair2, respectively. This metric is employed to measure the repeatability of a system and it is computed using Equation (2), where x and y represent the data from the HS image pair. Lower values of RD represent higher similarity. In the first experiment, Pair1 obtained a

of 9.52%, while in the second experiment (Pair2) the result was worsened due to the differences in the spatial coordinates of the PSL (

).

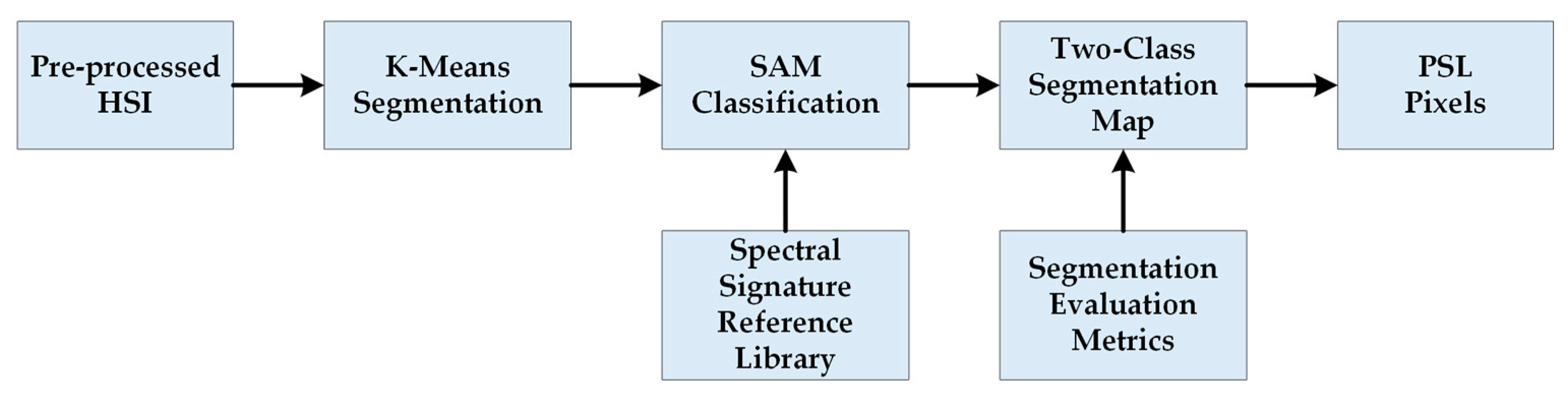

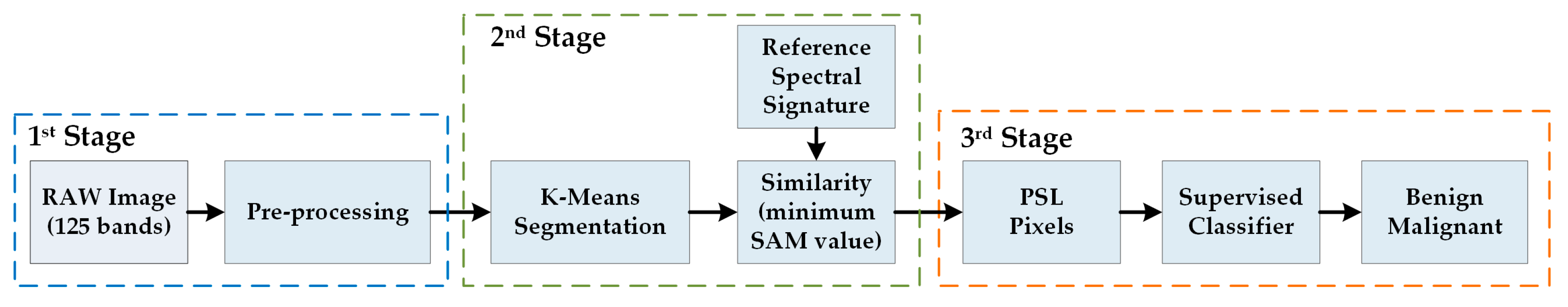

2.4. HS Dermatologic Segmentation Framework

In this section, a processing framework to automatically segment the captured HS image into normal skin and PSL pixels based on an unsupervised segmentation algorithm is proposed (

Figure 5). The PSL pixels identified in this framework will be afterwards classified into benign or malignant classes by the classification framework. The K-means clustering algorithm was selected to perform the segmentation as it is a well-established algorithm that provides a good delimitation of the different areas presented in an HS image scene [

25]. This algorithm divides an input HS image into

different clusters for a previously selected

value. However, the identification of each cluster is not associated to any pre-established class, so the segmentation maps only represent relevant spectral differences. In this framework, first, the evaluation of the optimal

value for this application is performed. Different clustering evaluation methods were employed to determine the optimal

value, such as Silhouette [

26], Calinski Harabasz [

27] and Davies Bouldin [

28] methods. The training dataset was used to find the optimal

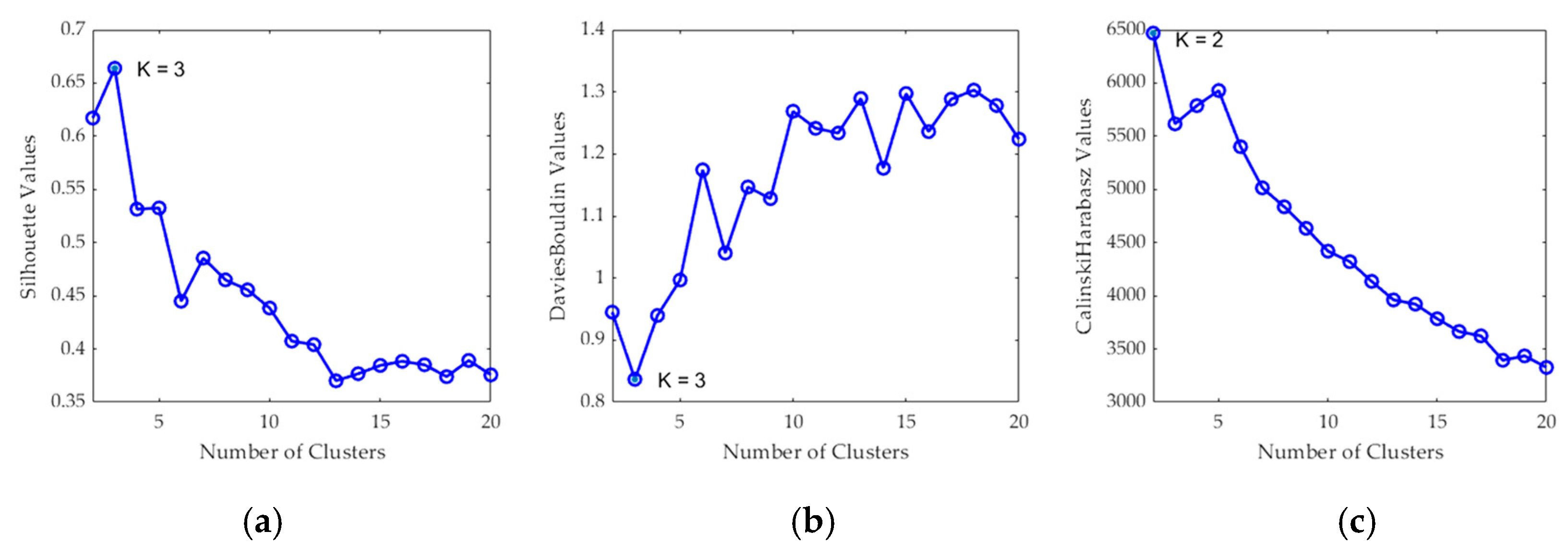

K value.

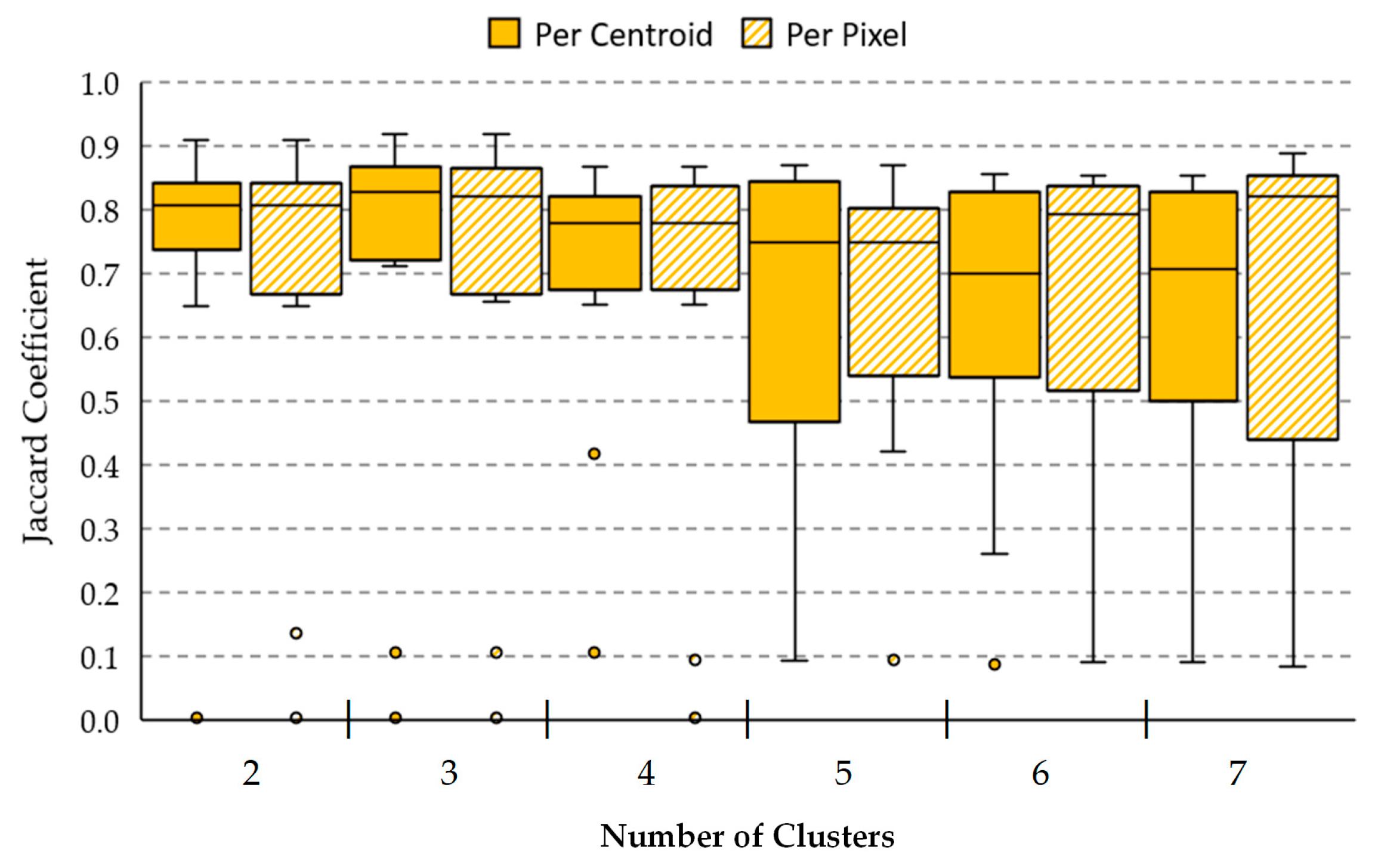

Table 2 shows the minimum and maximum

values obtained from the different methods, where the most frequent value to segment the image is two. Considering this result, the range between two and seven clusters will be evaluated to compare the results and select the

value that provides the best result.

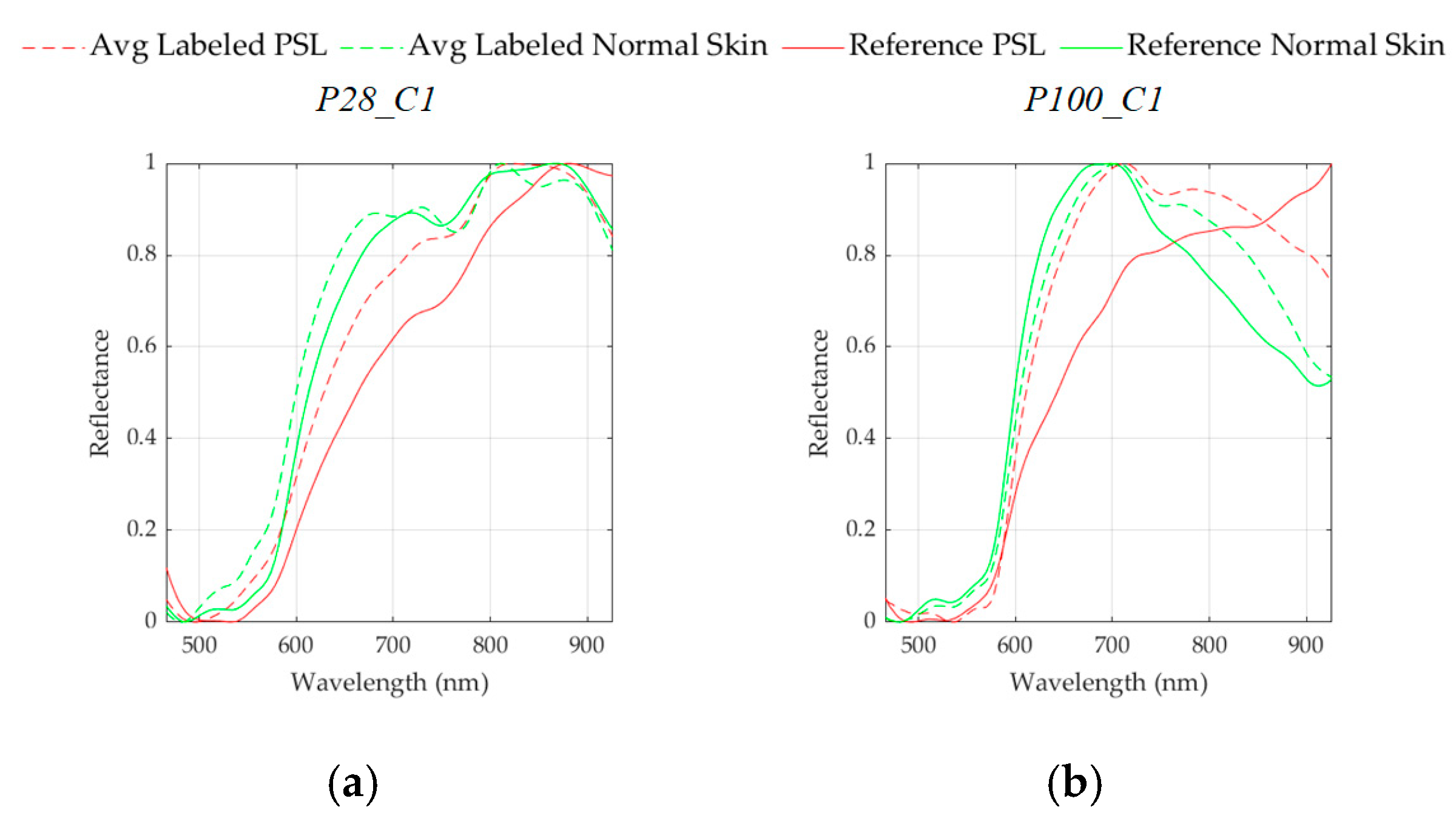

After the

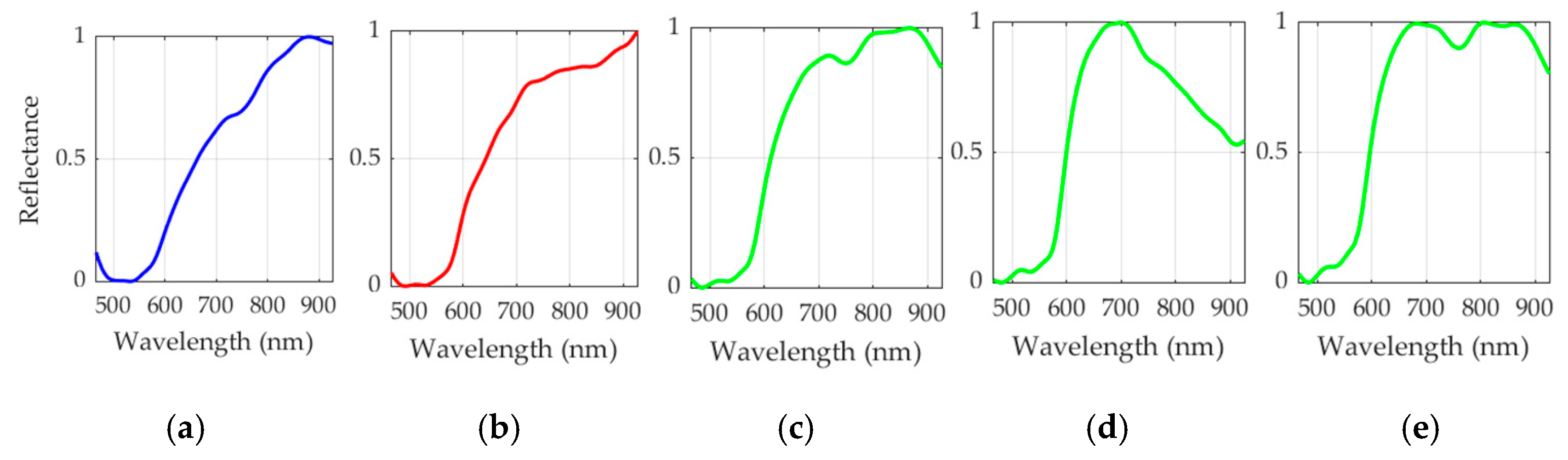

K value evaluation, a two-class segmentation map is generated where the PSL and the normal skin pixels are identified considering the information of each cluster of the segmentation map, using the SAM algorithm. In order to perform the SAM comparison, a spectral signature reference library of normal skin and PSL data was created, employing only the spectral signatures of the labeled training set in order to avoid the inclusion of validation or test HS images in the reference library (see

Section 2.2.2). This library contains five different spectral signatures: three from normal skin, and two from malignant and benign PSLs (see

Figure 6). These reference spectral signatures were obtained computing the average of the labeled data per class. The normal skin data were divided into three groups using the K-means clustering algorithm, where the number of clusters employed was selected after evaluating the results using the Silhouette, Calinski Harabasz and Davies Bouldin methods. The Silhouette and Davies Bouldin methods indicate that the optimal number of clusters to segment the normal skin data was three; taking into account the smallest index value achieved in

Figure 7a,b. Instead, for Calinski Harabasz method the optimal

K value was two, considering the highest index value reached in

Figure 7c. Taking into account these results, the selected number of clusters to segment the training set was established in three. These reference spectral signatures were employed to automatically identify the PSL pixels through the SAM algorithm, which will be next considered as input for the supervised classification.

For the computation of the SAM algorithm, two different methods were employed to generate the two-class segmentation maps. The first method (called

per centroid) compared the centroid from each cluster of the segmentation map with the spectral signatures of the reference library. In this method, the most similar spectral signature to each centroid was assigned to a certain class (PSL or normal skin). The second method (called

per pixel) compared each pixel in a certain cluster with the spectral signatures of the reference library and computed the sum of the resulting SAM values. Then, the smallest sum in each centroid is assigned to a certain class (PSL or normal skin). Finally, a morphological closing operation based on dilatation followed by erosion was applied to the two-class segmentation map in order to remove small isolated regions and to obtain a better representation of the lesion.

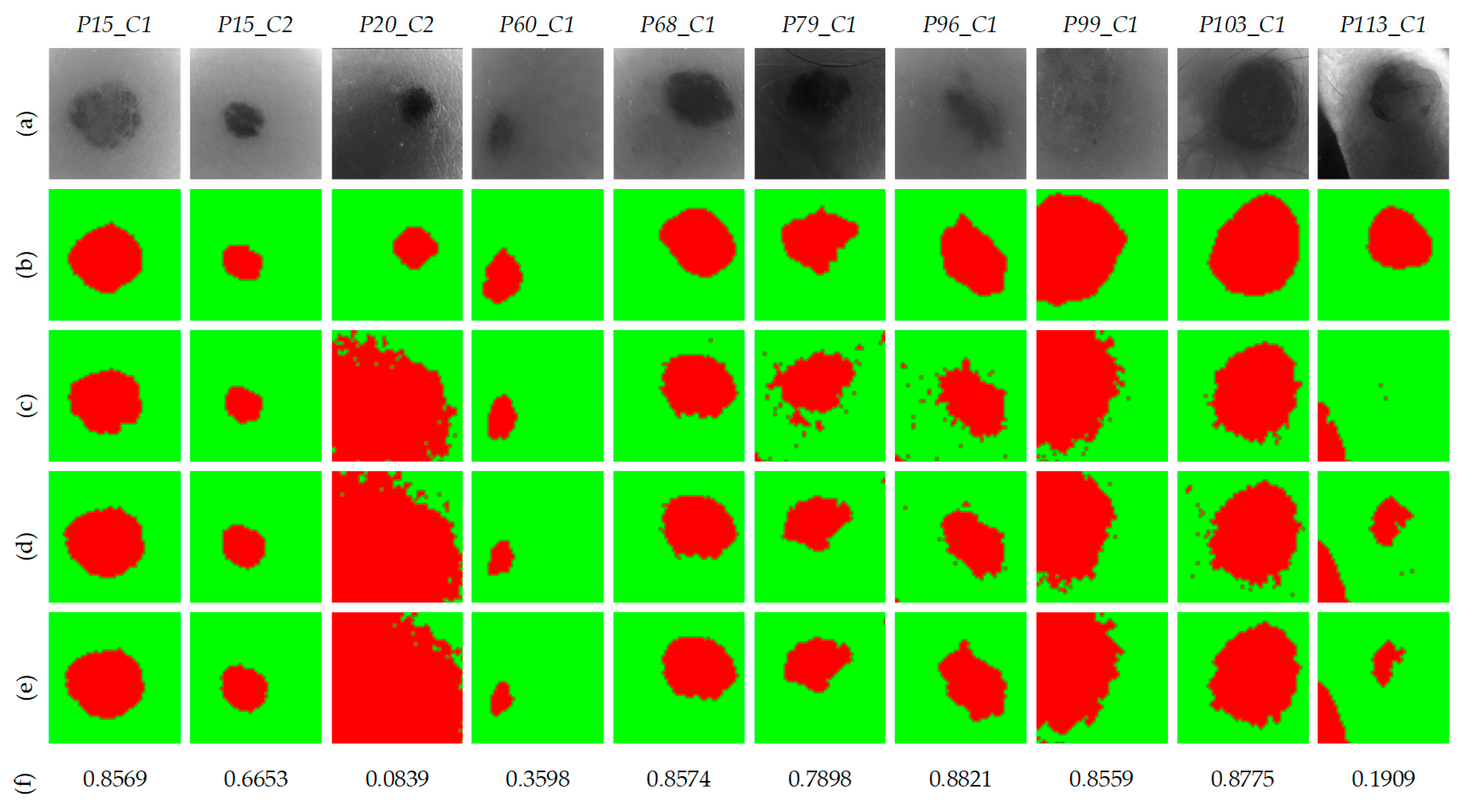

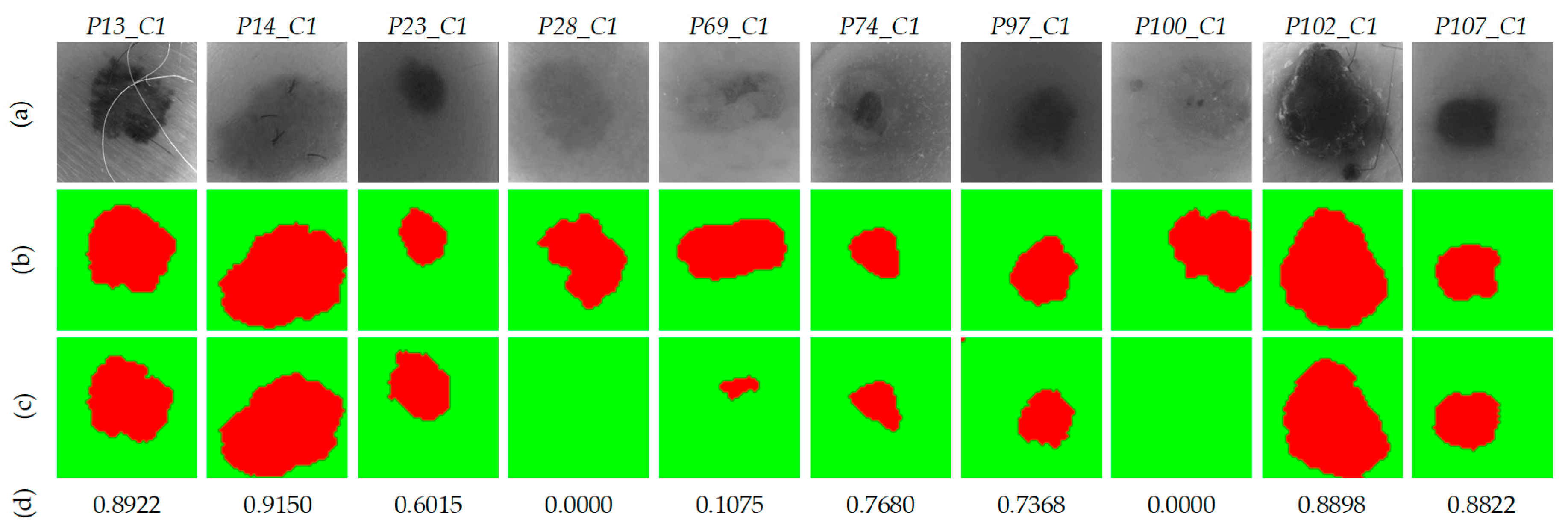

Figure 8 shows an example of a segmentation, where

Figure 8a shows the gray-scale image and

Figure 8b shows the segmentation map of an HS image using five clusters, where the colors have no physical meaning.

Figure 8c shows the classification map obtained after applying the SAM methodology, while

Figure 8d shows the same two-class segmentation map after the morphological post-processing. In these maps, normal skin and PSL pixels are represented in green and red colors, respectively.

Finally, these results were compared with the ground truth maps of the validation dataset using segmentation evaluation metrics to select the most appropriate value and SAM comparison method. The PSL pixels were used as input for the supervised classification in the complete processing framework.

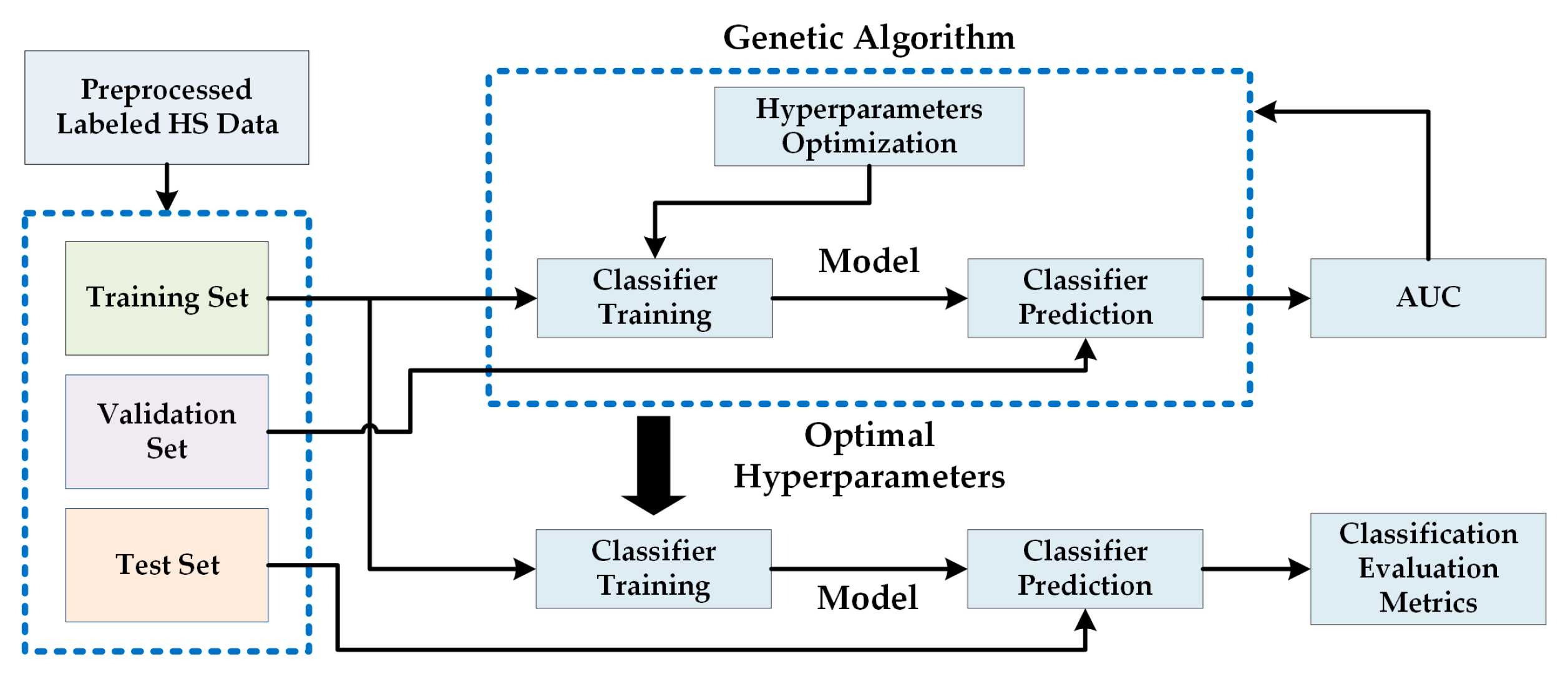

2.5. HS Dermatologic Classification Framework

The HS dermatologic classification framework developed in this work is based on a supervised classification with an automatic fine tuning of the classifier hyperparameters employing an optimization algorithm. The pre-processed HS labeled dataset was employed to find the most suitable classification model using the data partitions presented in

Section 2.7.2.

Figure 9 shows the block diagram of this processing framework, where a Genetic Algorithm (GA) was employed to optimize the hyperparameters of the supervised classifier using the training and validation sets. The area under the curve (AUC) was used for the evaluation of the validation results (see

Section 2.7). After finding the optimal hyperparameters, the classifier is trained with the training set and evaluated with the test set, obtaining the final evaluation metrics (see

Section 2.7.2). The supervised classification algorithms evaluated in this work are Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forest (RF) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [

29]. These classifiers have been commonly used for the classification of HS data in the literature, especially in medical HSI applications [

10].

2.5.1. Support Vector Machine (SVM) Classifier

The SVM classifier is a supervised classification algorithm [

30]. Its objective is to find out the best hyperplane that allows separating the different data with a maximum margin. The SVM was selected because it has been proven in the literature to perform well with highly imbalanced training datasets [

31], being also widely used for HS data classification in medical applications [

32,

33].

In this study, the linear, Radial Basis Function (RBF) and the sigmoid kernels were compared in performance for the SVM classifier. The optimal configuration of the SVM was adjusting by finding the optimal hyperparameters for each type of kernel.

Table S2 in the supplementary material shows the detailed kernel functions and their hyperparameters. LIBSVM was used for the SVM classifier implementation [

34].

2.5.2. Random Forest (RF) Classifier

The RF algorithm is an ensemble learning method capable of constructing a set of decision trees able to classify new data samples in a specific class by voting the decision trees predictions [

35]. RF can be optimized by establishing the most suitable number of trees in the classification model. This classifier was selected for evaluation since it has shown good performance in classifying medical HS data [

36]. To implement RF classifier, the MATLAB

® (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) Machine Learning ToolBox

TM was employed.

2.5.3. Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Classifier

The ANN classifier imitates the human brain process to transfer information [

37]. The optimization of the ANN model is performed with the objective of identifying the best number of

neurons for each layer. This classifier has been also employed in the literature to process HS medical data [

38]. The ANN architecture employed in this work was composed by four layers. Thus, four parameters were optimized in this classifier. To implement the ANN classifier, the MATLAB

® Deep Learning ToolBox

TM was used.

2.5.4. Genetic Algorithm (GA)

The GA is a non-linear global optimization algorithm proposed by Holland et al. in the late 1960s [

39]. The theory of the biological evolution (proposed by Charles Darwin) is the basis of this algorithm (survival of the fittest, crossover, mutation, etc.) [

40]. GA has been used in several types of optimization problems due to its straightforwardness and robustness [

41,

42,

43]. The GA implementation used in the experiments performed in this work was based on the MATLAB

® Global Optimization ToolBox

TM.

2.6. HS Dermatologic Framework for In-Situ Clinical Support

The complete processing framework is composed by three stages based on the three previously presented processing frameworks with the aim of supporting in-situ diagnosis of PSLs during clinical routine practice.

Figure 10 shows the block diagram of the complete processing framework where the different stages are interconnected. The first stage performs the pre-processing chain of the incoming raw HS image captured by the acquisition system. This pre-processed HS image is the input of the second stage, where the segmentation between PSL and normal skin pixels is performed. In the last stage, the pixels identified as PSL are classified, providing the dermatologist with the PSL class (Benign or Malignant) and the probability value of belonging to such class.

2.7. Evaluation Metrics

2.7.1. Segmentation Evaluation Metrics

Overlap-based metrics were employed to evaluate the segmentation quality achieved by the K-means algorithm, comparing the segmented image (

SI) against the ground truth (

GT). Dice similarity coefficient measures the match between two images and is equal to twice the intersection divided by the sum of the both images Equation (3) [

44]. Jaccard similarity coefficient measures the similarity between the

GT and

SI, being defined as the intersection over the union of the two images Equation (4) [

45]. These metrics are the most used in image segmentation evaluation and can be expressed using the definition of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN). Dice and Jaccard coefficients are similar metrics and both measurements have a value range in [0, 1]. However, Jaccard coefficient penalizes misclassifications more than Dice coefficient. For this reason, only the Jaccard coefficient will be employed in this work to select the optimal number of clusters (

) and the best segmentation methodology.

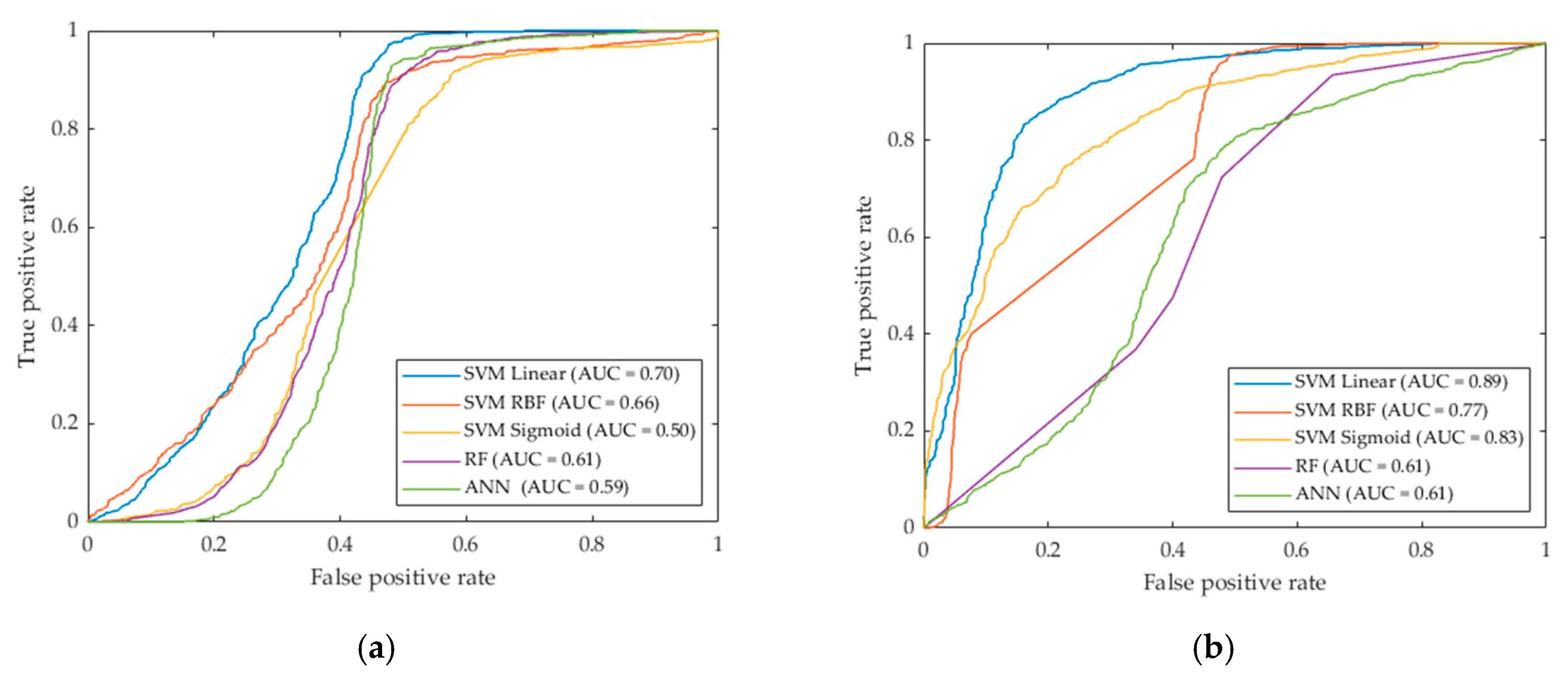

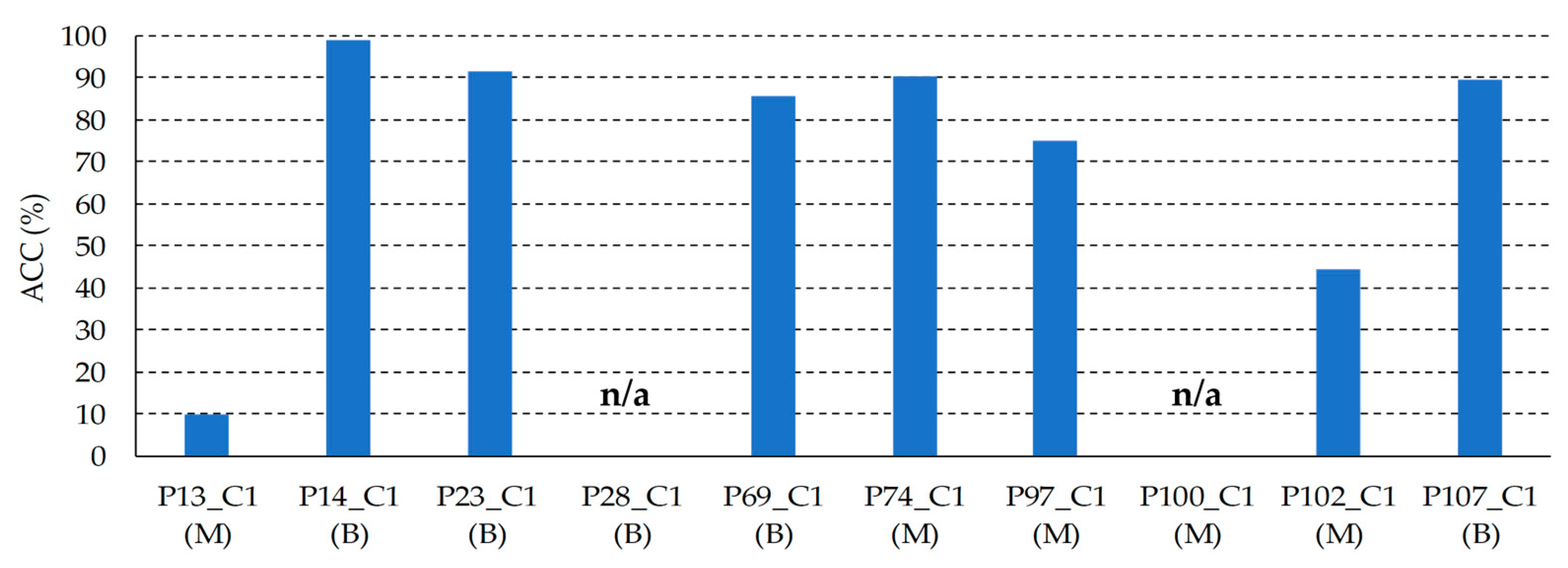

2.7.2. Classification Evaluation Metrics

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was employed to find the optimal hyperparameters of the supervised classifiers, finding the best performance using the AUC (Area Under the Curve) metric. The ROC curve represents how sensitivity changes with varying specificity and is used on binary classifications to determine if one variable is more predictive than another [

46]. Equations (5) and (6) presents the sensitivity and specificity expression where

is the number of true positives,

the number of false negatives,

the number of true negatives, and

the number of false positive.

In order to evaluate the results obtained for the optimized classifier (in both validation and test sets), the accuracy (

) metric was computed (see Equation (7)). For this particular application, when the evaluation of the complete framework is performed, the

is equivalent to the sensitivity of the classifier due to the pixels to be classified only belong to one class and there are no

TNs and

FPs.

5. Conclusions

The work presented in this paper had the goal of using HSI technology as a non-invasive clinical support system for diagnosing PSLs during dermatological routine practice. A customized HS dermatologic acquisition system for capturing HS data of PSLs was developed, obtaining an HS database composed by 76 images from 61 subjects. Using this HS database, a processing framework to classify the PSLs was proposed and validated using a methodology based on a three data partition fashion (train, validation and test sets), which provides an unbiased evaluation of the final processing model. The proposed framework isolates the PSL pixels in the HS image using a segmentation methodology, and classifies such pixels using a supervised classifier, with the main goal of achieving real-time processing for in-situ diagnosis support.

Two different image segmentation methods were proposed. Both methods combined the K-means and SAM algorithms to identify the PSL pixels using a reference spectral signature library of PSL and normal skin. The first one compared each cluster obtained by the K-means with the library, while the second one compared each pixel from each cluster from the K-means with the library. In addition, different classifiers were employed to obtain the most accurate results in the discrimination of the different types of PSL. The GA algorithm was used to find the optimal hyperparameters for each classifier. The results obtained showed SVM Linear classifier offered better results than the rest of the classifiers, providing an AUC value of 0.89. This preliminary study provides evidence that the combination of HSI and machine learning algorithms allows achieving promising differentiation of PSL types.