Abstract

Elderly women with ovarian cancer are often undertreated due to a perception of frailty. We aimed to evaluate the management of young, elderly and very elderly patients and its impact on survival in a retrospective multicenter study of women with ovarian cancer between 2007 to 2015. We included 979 women: 615 women (62.8%) <65 years, 225 (22.6%) 65–74 years, and 139 (14.2%) ≥75 years. Women in the 65–74 years age group were more likely to have serous ovarian cancer (p = 0.048). Patients >65 years had more >IIa FIGO stage: 76% for <65 years, 84% for 65–74 years and 80% for ≥75 years (p = 0.033). Women ≥75 years had less standard procedures (40% (34/84) vs. 59% (104/177) for 65–74 years and 72% (384/530) for <65 years (p < 0.001). Only 9% (13/139) of women ≥75 years had an Aletti score >8 compared with 16% and 22% for the other groups (p < 0.001). More residual disease was found in the two older groups (30%, respectively) than the younger group (20%) (p < 0.05). Women ≥75 years had fewer neoadjuvant/adjuvant cycles than the young and elderly women: 23% ≥75 years received <6 cycles vs. 10% (p = 0.003). Univariate analysis for 3-year Overall Survival showed that age >65 years, FIGO III (HR = 3.702, 95%CI: 2.30–5.95) and IV (HR = 6.318, 95%CI: 3.70–10.77) (p < 0.001), residual disease (HR = 3.226, 95%CI: 2.51–4.15; p < 0.001) and lymph node metastasis (HR = 2.81, 95%CI: 1.91–4.12; p < 0.001) were associated with lower OS. Women >65 years are more likely to have incomplete surgery and more residual disease despite more advanced ovarian cancer. These elements are prognostic factors for women’s survival regardless of age. Specific trials in the elderly would produce evidence-based medicine and guidelines for ovarian cancer management in this population.

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the seventh most common cancer in women (7.1/100,000 women) and the fourth cause of mortality by cancer in women. It accounts for an estimated 239,000 new cases and 152,000 deaths worldwide annually [1]. In France, its incidence is around 4700 new cases per year, and it is responsible for 3100 deaths [2]. The mean age at diagnosis is 65 years old with approximately 48% of patients older than 65 years [3], and outcomes generally worsen as the age of the patient increases [4]. Most patients with ovarian cancer are diagnosed at an advanced stage with a poor prognosis. Currently, although the 5-year relative survival rate for women with ovarian cancer increased from 36% in 1975–1977 [5] to 46% in 2005–2011 [6], it remains the most-deadly gynecological cancer.

Today, the standard treatment for ovarian cancer involves surgery and chemotherapy. To achieve complete cytoreduction, complex surgical procedures are necessary such as salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy, omentectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Bowel resection, pancreas resection, splenectomy, diaphragmatic stripping and partial liver resection may also be required and can lead to serious complications [7]. The benefit of this kind of treatment remains controversial in elderly patients considered frailer [8] and more prone to a higher rate of complications [9,10,11]. They are therefore often undertreated [12,13] in spite of the fact that some authors consider age to be an independent prognostic factor [14]. Data concerning the management of elderly patients with ovarian cancer are lacking since they have historically been under-represented in clinical trials [13,15,16]. As life expectancy increases (in the next few decades, approximately 20% of the world population will be over 65 years old [17]), the incidence of ovarian cancer in the elderly will rise. Oncologic management in this population is thus an emerging critical issue.

This study aimed to evaluate the management of young, elderly and very elderly patients with ovarian cancer in a large French multicenter cohort. We also studied overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), and cancer specific survival (CSS) rates.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patients

We collected data on women who had received surgical treatment for a histologically proven ovarian cancer between January 2000 and December 2016 from eight teaching hospitals in France (Creteil University Hospital, Jean Verdier University Hospital, Lille University Hospital, Poissy University Hospital, Tenon University Hospital, Tours University Hospital, Rennes University Hospital and Strasbourg University Hospital). All the data had been entered in a single ovarian cancer database. We excluded patients with no surgical treatment (thus, only chemotherapy patients were excluded), with non-epithelial ovarian carcinoma, benign tumors, and patients with unknown FIGO stage (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics system (FIGO)). The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Collège National des Gynécologues et Obstétriciens Français (CEROG 2016-GYN-1003).

2.2. Data Collection

The following demographic and clinical data were collected: age, body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters), parity and Ca125 at diagnosis. Preoperative assessment of surgical risk was performed according to the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) Physical Status Classification by the attending anesthesiologist at the time of surgery [18]. The type of surgical procedure, pathologic data (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics system (FIGO) stage), nodal status and adjuvant therapy were also collected. Patients were divided into three cohorts: young women (aged < 65 years), elderly women (aged 65–74 years), and very elderly women (aged ≥ 75 years).

2.3. Histology

Tumors were classified according to their pathologic status. Histologic subtypes were classified as serous adenocarcinoma, endometroid, mucinous, clear-cell and mixed epithelial tumors. Patients were then graded according to the FIGO 2014 classification [19].

2.4. Treatment

Cytoreductive surgery performed before chemotherapy was called “primary debulking surgery,” and when performed after chemotherapy it was called “interval debulking surgery” or “surgery after 6 cycles.” The treatment sequence was determined on an individual basis according to the patient’s general condition, exam results (CT scan, MRI…), and after multidisciplinary concertation. Standard surgery for ovarian cancer consists of hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Bowel resection, pancreas resection, splenectomy, diaphragmatic stripping and partial liver resection may also be required to achieve complete cytoreduction.

The surgical procedures were classified according to Luyckx et al.’s publication [20]: Group 1 included standard surgery with hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, rectosigmoid resection, infragastric omentectomy, pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy, and, when applicable, appendectomy; Group 2A included standard surgery plus relatively routine upper abdominal surgery such as stripping of the diaphragmatic peritoneum and splenectomy alone; and Group 2B included ultra-radical surgeries involving a combination of digestive tract resections (right colon and caecum, total colectomy, and others), organ resection (spleen, gallbladder, partial gastrectomy, and others), celiac lymph node dissection, and total abdominal peritoneum stripping in addition to standard surgery.

We evaluated the complexity of the surgical procedure using Aletti’s surgical complexity score (SCS) [3]. This score classifies the surgical complexity including associated procedures in three groups: low (≤3), intermediate (4–7) and high (≥8).

Surgery complications were assessed according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [21] as minor (grades I and II) or major (grades III, IV and V). Minor complications included anemia, occlusion, wall abscess, pneumonia, lymphocele, thrombosis, and major complications were lymphocele puncture, pleural effusion drainage, pulmonary embolism, organ failure, sepsis, hemorrhage, requirement for repeat surgery, or death.

Adjuvant therapies included chemotherapy and bevacizumab. Chemotherapy was based on platinum salts (CARBOPLATINE AU5 or AU6) and taxanes (PACLITAXEL 175 mg/m2) every 3 weeks with at least 6 cycles. The chemotherapy protocol or bevacizumab administration was modified on an individual basis after multidisciplinary concertation.

2.5. Follow-Up Assessment

Clinical follow-up consisted of physical examinations and the use of imaging techniques according to the clinical findings during visits conducted every 3 months for the first 2 years, every 6 months for the following 3 years, and once a year thereafter.

2.6. Outcome Measures

The outcome measures were OS (overall survival), DFS (disease free survival), and CSS (cancer specific survival) rates calculated from date of recurrence, date of death, and date of cancer-related death. We also analyzed the rates and types of Clavien-Dindo complications.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive parameters were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Frequencies were presented as percentages. Chi square and Fisher’s exact tests were used as appropriate for categorical or ordinal variables. For continuous variables, t tests were used to compare two variables, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for more than two variables.

OS was calculated in months from the date of surgery to death (related or unrelated to cancer) or to the date of the last follow-up visit for surviving patients. CSS was calculated as the time from the date of surgery to cancer-related death, and DFS was calculated as the time from the surgery to cancer recurrence. Women who were alive and without recurrence were censored at the date of the last follow-up visit. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the survival distribution. Tick marks indicate censored data. The comparison test chosen for analysis of survival was the log-rank test. Effects were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Cox proportional hazard models included established prognostic factors: age, FIGO status, lymph node metastasis, residual disease, Aletti’s SCS, and complications. In the multivariate analysis, missing data were considered as absent. A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

Of the 1171 women with ovarian cancer who received surgical treatment during the study period, 144 were excluded from analysis because of no surgical treatment (41 with only chemotherapy and seven patients without any curative treatment), a non-epithelial ovarian carcinoma or no FIGO stage reported. The distribution of the remaining 979 women in the three age groups was as follows: 615 women (62.8%) aged 65 years or younger, 225 women (22.6%) aged 65–74 years, and 139 women (14.2%) aged 75 years or older (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of patient inclusion.

The mean age at diagnosis was 60.1 years (±12.7). The demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of the whole cohort by age group are reported in Table 1. The number of comorbidities was higher in the older groups (70% of the elderly and 66% of the very elderly patients had three or more comorbidities vs. 23% of the young patients, p < 0.001). The ASA score was higher in the oldest group: 32/139 (23%) vs. 51/615 (8%) in the young group (p < 0.001). The tumor characteristics are reported in Table 1. The pathologic subtype was serous, endometrioid, mucinous, mixed and clear-cell for 66%, 11%, 5%, 12 and 6%, respectively, for the whole population. More women in the 65–74-year age group had serous ovarian cancer (vs. other epithelial tumors) (p = 0.048) (Table 1). Patients older than 65 years had more advanced FIGO stage (i.e., >IIa): 76% for <65-year group, 84% for 65–74-year group, and 80% for ≥75-year group (p = 0.033). There was no significant difference concerning the presence of lymph node metastasis (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient and Tumor Characteristics.

Table 2.

Treatment Characteristics.

3.2. Surgical Procedures and Adjuvant Therapies

The surgical procedures are described in Table 2. Thirty-three percent of the elderly women (67/225) had primary cytoreductive surgery vs. 44% (242/625) of the young patients and 40% (45/139) of the very elderly (p < 0.05). According to the surgical procedure groups described by Luyckx [20], the very elderly had fewer standard procedures (40% (34/84) vs. 59% (104/177) for the elderly and 72% (384/530) for the young patients, (p < 0.001)). The very elderly patients had significantly fewer pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomies (49% for ≥75 years, 70% for 65–74 years, and 80% for <65 years, p < 0.001) with fewer lymph nodes removed among those who underwent a para-aortic lymphadenectomy (p < 0.05). The very elderly also had less upper-abdominal surgery (11%, 15/139) than the elderly (21%, 47/171) and young patients (23%, 139/615) (p < 0.05). Only 9% (13/139) of the very elderly had an Aletti’s SCS higher than eight compared with 16% and 22% for the elderly and young groups, respectively (p < 0.001). There was more residual disease in the two older groups (30%) than for younger women (20%) (p < 0.05).

Adjuvant treatments are displayed in Supplementary Data (Table S1). No adjuvant chemotherapy was performed in 21% (24/139) of the very elderly patients, 14% (28/225) of the elderly and 13% (71/615) of the young patients (p = 0.084). When chemotherapy was conducted, the very elderly were administered fewer cycles (neoadjuvant plus adjuvant) compared with the elderly and the young: 23% of the very elderly received fewer than six cycles vs. 10% in the two other groups (p = 0.003). Only 12% (11/139) of the very elderly women received bevacizumab compared with 26% (112/615) of the young patients and 20% (30/225) of the elderly (p < 0.05).

3.3. Perioperative Complications

There was no difference in minor and major Clavien-Dindo complications in the three groups (p = 0.164 for minor complications and p = 0.567 for major complications). No significant difference in the rate of postoperative complications was observed (21.3% in the group <65 years, 20.9% in the group 65–74 years and 17.3% in the group ≥75 years) whether in terms of transfusion, digestive, urinary and pulmonary complications, complications of the abdominal wall, infections or repeat surgery. No patients died in the young group whereas one patient died postoperatively in each of the older groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Three-year disease-free survival, cancer-specific survival and overall survival rates (univariate analysis).

3.4. Survival Results

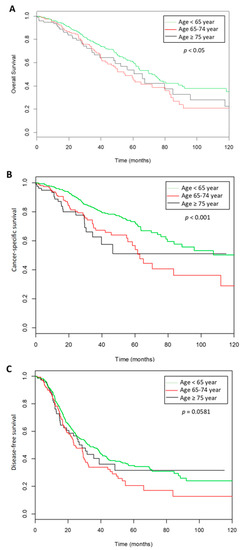

The mean follow-up was 36 months (±29.3). Recurrences were observed in 511 of the 979 women (52.2%) with a mean time of recurrence of 26.68 months (±24.7). In the whole population, the 3-year DFS was 44% (95% CI: 39.8–48.8), the 3-year CSS was 76.4% (95% CI: 72.4–80.5) and the 3-year OS was 71% (95% CI: 67.4–75.2) (Figure 2). Three-year DFS, CSS and OS rates for the three age groups are described in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Survival curves according the three groups of ages. (A). Overall survival, (B). cancer specific survival, (C). disease free survival.

Univariate analysis for the 3-year OS showed that an age over 65 years, a FIGO stage III (HR = 3.702, 95% CI: 2.30–5.95) or IV (HR = 6.318, 95% CI: 3.70–10.77) (p < 0.001), residual disease (HR = 3.226, 95% CI: 2.51–4.15; p < 0.001) and lymph node metastasis (HR = 2.81, 95%CI: 1.91–4.12; p < 0.001) were significantly associated with a lower OS. The multivariate analysis is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Three-year disease-free survival, cancer-specific survival and overall survival rates (multivariate analysis).

4. Discussion

The present study highlights that women over 65 years old with ovarian cancer undergo less radical surgery due to higher comorbidities even though they present with more advanced FIGO stage disease. Surgical treatment was found to be less complex for the elderly, resulting in similar postoperative complications, whether minor or major, as in the younger patients. Similarly, for systemic treatment, the elderly were less likely to have six chemotherapy cycles or be administered a targeted therapy such as bevacizumab. These findings are concordant with those in the literature [8,11,13,16,22,23]. Thus, due to a higher advanced FIGO stage and less optimal treatment in elderly ovarian cancer patients, age is significantly correlated with poorer prognosis in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer, as prior studies have described [8,9,14,16,24].

The fact that elderly patients with more comorbidities have similar perioperative complications suggests that surgeons consider these patients to be frailer and perform less radical surgery to limit morbidity [25]. However, residual disease was an important prognostic factor in OS (HR = 3.226, 95% CI: 2.51–4.15; p < 0.001) independently of age [25], and the elderly could benefit from complete cytoreductive surgery. Decisions to adjust treatment protocols are often guided by chronological age, which is illustrated in clinical trials which tend to recruit young patients [26,27]. With 70% of complete cytoreduction surgery in the elderly and very elderly patients, our rate was higher than that described in literature (29.5% between 60 and 79 years old [5], and 21.7 to 25 % for patients older than 80 years old in the SEER database [11,13]). Based on the SEER database, Warren et al. reported that in an ovarian cancer patient over 75 years of age, an appropriate surgery, an appropriate chemotherapy, and both surgery and chemotherapy were only realized, respectively, 37.6% (OR = 0.58 (IC 95% 0.40–0.83)), 51.2% (OR = 0.27 (IC 95% 0.17–0.41)) and 18.9% (OR = 0.36 (IC 95% 0.28–0.530)) [28]. Cloven et al. showed that only 21.7% of patients older than 80 years of age were optimally cytoreduced (73.7% for patients < 60 years old and 29.5% between 60 and 79 years old) [13]. For Gershenson et al., patients older than 65 were correctly debulked half as often as younger patients (33% vs. 61%) [29].

This may explain the similar OS and CSS rates for both age groups older than 65 years and would seem to indicate that 65 years marks a threshold of two groups of ovarian cancer patients that require different guidelines of therapeutic management. However, adapting standardized treatment guidelines for women over 65 years with ovarian cancer is hampered by a lack of evidence-based medicine as elderly patients are historically under-represented in clinical trials [15] [30,31,32]. Frailty is a common finding in patients with ovarian cancer and is independently associated with worse surgical outcomes and poorer OS. Kumar et al. showed that frailty was independently associated with death (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.21–1.92) after adjusting for known risk factors [33]. Median survival time was in favor of younger patients (98 vs. 30 months) and less frail patients (56 vs. 27 months) [34]. Although routine assessments of frailty can be incorporated into patient counseling and decision-making for the ovarian cancer patient beyond simple reliance on single factors such as age, there are no prospective studies on the effects of age or frailty on modifications to surgical approaches, postoperative complications, or prognosis in elderly women with ovarian cancer.

Adjuvant treatment in this population is also a subject of debate. In our study, very elderly patients received less adjuvant treatment than their younger counterparts and fewer cycles. Although several studies [13,35,36,37] have demonstrated that patients older than 70 years tolerate standard chemotherapy with similar rates of initial response and with an improved median OS of six months [38,39,40], the probability of receiving chemotherapy decreases with age [23] and the number of comorbidities [41]. There are currently minimal data evaluating the effectiveness and safety of bevacizumab in elderly women, but Amadio et al. showed that the occurrence of serious (grade ≥3) adverse events did not increase among the older group [42]. Besides, Perren and al. [43] demonstrated its effectiveness in women with residual disease or FIGO 4 status. As elderly patients are more likely to have residual disease, we believe that they could be good candidates for this therapy.

One of the strengths of our study is the high number of patients included from eight centers. However, our study has limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the data. We did not have validated cut-offs to categorize patients as “elderly” or “very elderly,” so comparison with other studies is difficult. However, there is no current consensus to define elderly women. We chose to classify women into three groups—“young” (<65 years), “elderly” (65–74 years), and “very elderly” (≥75 years)—whereas Yancik et al. [44] made the distinction between the “young” old (65–74 years), “older” old (75–84 years) and “oldest” old (≥85 years). Some reports chose a cut-off at 65 years old [38], others at 70 [37,45] or 75 years old [46], and some up to 80 years old [12,13]. Another limitation is linked to the retrospective nature of the study with incomplete data sets (such as ICU transfer, hospital stay, or unplanned 30 days). Furthermore, we did not know the reasons for cessation of chemotherapy, especially in the older age group. Of note, these points were evaluated in a previous publication which showed that hematological and cardiovascular toxicities were more frequent in elderly patients, but this did not influence prior discontinuation of therapy [47]. In addition, all the patients were managed in an expert center by surgeons specializing in oncologic gynecology who usually perform complete standard care (a combination of surgery and chemotherapy) [48]. Therefore, they might not be representative of all elderly women with ovarian cancer. In the same way, a common concern with observational data is the potential for selection bias, in which unobserved dimensions of health status, such as performance status, may determine treatment and independently affect survival as we described above. Indeed, the number of comorbidities was significantly higher in the elderly patients. Similarly, elderly patients who did not undergo lymphadenectomy received adjuvant treatment less often than the elderly patients who did (p = 0.07), implying that patient care is influenced, at least in part, by subjective evaluation of health status. The high burden of medical comorbidities, financial and geographic barriers to care, as well as patient preferences, may influence treatment and survival [36]. Nevertheless, similar to other studies, no objective evaluation was used to tailor surgical staging or adjuvant treatment. Lastly, patients were included before three milestone publications that led to modifications in national and international recommendations for the management of ovarian cancer in 2019 [49,50]: a reduced indication for lymphadenectomy in ovarian cancer because of the results of the LION (lymphadenectomy in ovarian neoplasms) study [51], the place of olaparib in patients with BRCA (breast cancer) mutations [52], and the use of hyperthermique intra-peritoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) [53].

5. Conclusions

The incidence of ovarian cancer is increasing with the aging of the population. Currently, elderly and very elderly women are at risk of incomplete surgery with less upper abdominal surgery and more residual disease, despite having more aggressive ovarian cancer. These elements are prognostic factors for women’s survival regardless of age. Moreover, they also have less adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy and bevacizumab) because they are perceived as being too frail to tolerate these treatments. Elderly oncology patients should undergo individual oncogeriatric assessment to determine the risk/benefit balance of therapy. To do so, specific trials dedicated to the elderly should be performed to generate evidence-based medicine and guidelines for the management of elderly patients with cancer, specifically in ovarian cancer, which requires aggressive surgery and systemic treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/9/5/1451/s1, Table S1: Perioperative Complications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.L., Y.J. and L.D.; methodology, Y.J., L.D., C.M., S.B., V.L.; software, C.M. and C.H.; validation, Y.J., L.D., C.M., K.N.T., S.B., A.B., P.C. (Pauline Chauvet), P.C. (Pierre Collinet), C.T., L.O., H.A., Y.D., C.A., G.C., P.-A.B., H.C., M.M., T.G., F.K., N.B., M.K., X.C., E.R., O.G., L.L., M.B., J.L., C.H. and V.L.; formal analysis, L.D., C.M., C.H. and V.L.; investigation, K.N.T., S.B., A.B., C.T., L.O., H.A., Y.D., C.A., G.C., P.-A.B., H.C., M.M., T.G., F.K., P.C. (Pauline Chauvet), P.C. (Pierre Collinet), N.B., M.K., X.C., E.R., O.G., L.L., M.B., J.L., C.H. and V.L.; data curation, K.N.T., S.B., A.B., P.C. (Pauline Chauvet), C.T., L.O., H.A., Y.D., C.A., G.C., P.-A.B., H.C., M.M., T.G., F.K., P.C. (Pauline Chauvet), P.C. (Pierre Collinet), N.B., M.K., X.C., E.R., O.G., L.L., M.B., J.L., C.H. and V.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.J., L.D. and V.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.J., L.D., C.M., C.H. and V.L.; supervision, V.L.; project administration, K.N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesari, M.; Cerullo, F.; Zamboni, V.; Di Palma, R.; Scambia, G.; Balducci, L.; Antonelli Incalzi, R.; Vellas, B.; Gambassi, G. Functional status and mortality in older women with gynecological cancer. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aletti, G.D.; Dowdy, S.C.; Podratz, K.C.; Cliby, W.A. Relationship among surgical complexity, short-term morbidity, and overall survival in primary surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 197, 676-e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.D.; Chen, L.; Tergas, A.I.; Patankar, S.; Burke, W.M.; Hou, J.Y.; Neugut, A.I.; Ananth, C.V.; Hershman, D.L. Trends in relative survival for ovarian cancer from 1975 to 2011. Obstet. Gynecol 2015, 125, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ries, L.A. Ovarian cancer. Survival and treatment differences by age. Cancer 1993, 71, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlader, N.; Ries, L.A.; Mariotto, A.B.; Reichman, M.E.; Ruhl, J.; Cronin, K.A. Improved estimates of cancer-specific survival rates from population-based data. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 1584–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, R.E.; Tomacruz, R.S.; Armstrong, D.K.; Trimble, E.L.; Montz, F.J. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.N.; Reid, M.S.; Fong, D.N.; Myers, T.K.; Landrum, L.M.; Moxley, K.M.; Walker, J.L.; McMeekin, D.S.; Mannel, R.S. Ovarian cancer in the octogenarian: Does the paradigm of aggressive cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy still apply? Gynecol. Oncol. 2008, 110, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, D.S.; Dahlberg, S.; Green, S.J.; Garcia, D.; Hannigan, E.V.; O’toole, R.; Stock-Novack, D.; Surwit, E.A.; Malviya, V.K.; Jolles, C.J. Analysis of patient age as an independent prognostic factor for survival in a phase III study of cisplatin-cyclophosphamide versus carboplatin-cyclophosphamide in stages III (suboptimal) and IV ovarian cancer. A Southwest Oncology Group study. Cancer 1993, 71, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancik, R.; Ries, L.G.; Yates, J.W. Ovarian cancer in the elderly: An analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program data. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1986, 154, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hightower, R.D.; Nguyen, H.N.; Averette, H.E.; Hoskins, W.; Harrison, T.; Steren, A. National survey of ovarian carcinoma. IV: Patterns of care and related survival for older patients. Cancer 1994, 73, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Montes, T.P.; Zahurak, M.L.; Giuntoli II, R.L.; Gardner, G.J.; Gordon, T.A.; Armstrong, D.K.; Bristow, R.E. Surgical care of elderly women with ovarian cancer: A population-based perspective. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 99, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloven, N.G.; Manetta, A.; Berman, M.L.; Kohler, M.F.; DiSaia, P.J. Management of ovarian cancer in patients older than 80 years of Age. Gynecol. Oncol. 1999, 73, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thigpen, T.; Brady, M.F.; Omura, G.A.; Creasman, W.T.; McGuire, W.P.; Hoskins, W.J.; Williams, S. Age as a prognostic factor in ovarian carcinoma. The Gynecologic Oncology Group experience. Cancer 1993, 71, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.H.; Kilgore, M.L.; Goldman, D.P.; Trimble, E.L.; Kaplan, R.; Montello, M.J.; Housman, M.G.; Escarce, J.J. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. Oncol. 2003, 21, 1383–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, M.; Lewis, J.L., Jr.; Saigo, P.; Hakes, T.; Jones, W.; Rubin, S.; Reichman, B.; Barakat, R.; Curtin, J.; Almadrones, L.; et al. Epithelial ovarian cancer in the elderly. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Cancer 1993, 71, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.K.; Howe, H.L.; Ries, L.A.; Thun, M.J.; Rosenberg, H.M.; Yancik, R.; Wingo, P.A.; Jemal, A.; Feigal, E.G. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1999, featuring implications of age and aging on U.S. cancer burden. Cancer 2002, 94, 2766–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hightower, C.E.; Riedel, B.J.; Feig, B.W.; Morris, G.S.; Ensor, J.E., Jr.; Woodruff, V.D.; Daley-Norman, M.D.; Sun, X.G. A pilot study evaluating predictors of postoperative outcomes after major abdominal surgery: Physiological capacity compared with the ASA physical status classification system. Br. J. Anaesth. 2010, 104, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hohn, A.K.; Einenkel, J.; Wittekind, C.; Horn, L.C. New FIGO classification of ovarian, fallopian tube and primary peritoneal cancer. Pathologe 2014, 35, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, M.; Leblanc, E.; Filleron, T.; Morice, P.; Darai, E.; Classe, J.M.; Ferron, G.; Stoeckle, E.; Pomel, C.; Vinet, B.; et al. Maximal cytoreduction in patients with FIGO stage IIIC to stage IV ovarian, fallopian, and peritoneal cancer in day-to-day practice: A retrospective French multicentric study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2012, 22, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyar, D.; Frasure, H.E.; Markman, M.; Von Gruenigen, V.E. Treatment patterns by decade of life in elderly women (> or =70 years of age) with ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. Oncol. 2005, 98, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundararajan, V.; Hershman, D.; Grann, V.R.; Jacobson, J.S.; Neugut, A.I. Variations in the use of chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer: A population-based study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancik, R.; Moore, T.D.; Martin, G.; Obrams, G.I.; Reed, E. Older women as the focus for research and treatment of ovarian cancer. An overview for the National Institute on Aging, National Cancer Institute, and American Cancer Society Multidisciplinary Working Conference. Cancer 1993, 71, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, W. Clinical trials in elderly ovarian cancer patients—Does it make sense? Onkologie 2012, 35, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, L.; Vizzielli, G.; Fusco, D.; Cho, W.C.; Bernabei, R.; Scambia, G.; Colloca, G. Ovarian cancer management in the oldest old: Improving outcomes and tailoring treatments. Aging Dis. 2017, 8, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, P.; Harugeri, A. Elderly patients’ participation in clinical trials. Perspect Clin. Res. 2015, 6, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, J.L.; Harlan, L.C.; Trimble, E.L.; Stevens, J.; Grimes, M.; Cronin, K.A. Trends in the receipt of guideline care and survival for women with ovarian cancer: A population-based study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 145, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenson, D.M.; Mitchell, M.F.; Atkinson, N.; Silva, E.G.; Burke, T.W.; Morris, M.; Kavanagh, J.J.; Warner, D.; Wharton, J.T. Age contrasts in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. The M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer 1993, 71, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, L.F.; Unger, J.M.; Crowley, J.J.; Coltman, C.A.; Albain, K.S. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 2061–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, K.W.; Pater, J.L.; Pho, L.; Zee, B.; Siu, L.L. Enrollment of older patients in cancer treatment trials in Canada: Why is age a barrier? J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 1618–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, E.L.; Carter, C.L.; Cain, D.; Freidlin, B.; Ungerleider, R.S.; Friedman, M.A. Representation of older patients in cancer treatment trials. Cancer 1994, 74, 2208–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Langstraat, C.L.; DeJong, S.R.; McGree, M.E.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.N.; Weaver, A.L.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Cliby, W.A. Functional not chronologic age: Frailty index predicts outcomes in advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 147, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, A.; Fuso, L.; Tripodi, E.; Tana, R.; Daniele, A.; Zanfagnin, V.; Perotto, S.; Gadducci, A. Ovarian cancer in elderly patients: Patterns of care and treatment outcomes according to age and modified frailty index. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccaroni, M.; D’Agostino, G.; Ferrandina, G.; Gadducci, A.; Di Vagno, G.; Pignata, S.; Poerio, A.; Salerno, M.G.; Fanucchi, A.; Lapresa, M.T.; et al. Gynecological malignancies in elderly patients: Is age 70 a limit to standard-dose chemotherapy? An Italian retrospective toxicity multicentric study. Gynecol. Oncol. Oncol. 2002, 85, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villella, J.; Chalas, E. Optimising treatment of elderly patients with ovarian cancer: Improving their enrollment in clinical trials. Drugs Aging 2005, 22, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruchim, I.; Altaras, M.; Fishman, A. Age contrasts in clinical characteristics and pattern of care in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. Oncol. 2002, 86, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer, E.L.; Tew, W.P.; Levine, D.A.; Lichtman, S.M.; Brown, C.L.; Aghajanian, C.; Huh, J.; Barakat, R.R.; Chi, D.S. Response and outcomes in elderly patients with stages IIIC-IV ovarian cancer receiving platinum-taxane chemotherapy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 106, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershman, D.; Fleischauer, A.T.; Jacobson, J.S.; Grann, V.R.; Sundararajan, V.; Neugut, A.I. Patterns and outcomes of chemotherapy for elderly patients with stage II ovarian cancer: A population-based study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2004, 92, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilpert, F.; du Bois, A.; Greimel, E.R.; Hedderich, J.; Krause, G.; Venhoff, L.; Loibl, S.; Pfisterer, J. Feasibility, toxicity and quality of life of first-line chemotherapy with platinum/paclitaxel in elderly patients aged > or =70 years with advanced ovarian cancer—A study by the AGO OVAR Germany. Ann. Oncol. 2007, 18, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairfield, K.M.; Murray, K.; Lucas, F.L.; Wierman, H.R.; Earle, C.C.; Trimble, E.L.; Small, L.; Warren, J.L. Completion of adjuvant chemotherapy and use of health services for older women with epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3921–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amadio, G.; Marchetti, C.; Villani, E.R.; Fusco, D.; Stollagli, F.; Bottoni, C.; Distefano, M.; Colloca, G.; Scambia, G.; Fagotti, A. ToleRability of BevacizUmab in elderly ovarian cancer patients (TURBO study): A case-control study of a real-life experience. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 31, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perren, T.J.; Swart, A.M.; Pfisterer, J.; Ledermann, J.A.; Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Kristensen, G.; Carey, M.S.; Beale, P.; Cervantes, A.; Kurzeder, C.; et al. A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2484–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancik, R. Cancer burden in the aged: An epidemiologic and demographic overview. Cancer 1997, 80, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chereau, E.; Ballester, M.; Selle, F.; Rouzier, R.; Darai, E. Ovarian cancer in the elderly: Impact of surgery on morbidity and survival. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 37, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alphs, H.H.; Zahurak, M.L.; Bristow, R.E.; Diaz-Montes, T.P. Predictors of surgical outcome and survival among elderly women diagnosed with ovarian and primary peritoneal cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2006, 103, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woopen, H.; Inci, G.; Richter, R.; Chekerov, R.; Ismaeel, F.; Sehouli, J. Elderly ovarian cancer patients: An individual participant data meta-analysis of the North-Eastern German Society of Gynecological Oncology (NOGGO). Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 60, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, R.E.; Zahurak, M.L.; Diaz-Montes, T.P.; Giuntoli, R.L.; Armstrong, D.K. Impact of surgeon and hospital ovarian cancer surgical case volume on in-hospital mortality and related short-term outcomes. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 115, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoue, V.; Huchon, C.; Akladios, C.; Alfonsi, P.; Bakrin, N.; Ballester, M.; Bendifallah, S.; Bolze, P.A.; Bonnet, F.; Bourgin, C.; et al. Management of epithelial cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneum. Long text of the Joint French Clinical Practice Guidelines issued by FRANCOGYN, CNGOF, SFOG, and GINECO-ARCAGY, and endorsed by INCa. Part 1: Diagnostic exploration and staging, surgery, perioperative care, and pathology. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 48, 369–378. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoue, V.; Huchon, C.; Akladios, C.; Alfonsi, P.; Bakrin, N.; Ballester, M.; Bendifallah, S.; Bolze, P.A.; Bonnet, F.; Bourgin, C.; et al. Management of epithelial cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, primary peritoneum. Long text of the joint French clinical practice guidelines issued by FRANCOGYN, CNGOF, SFOG, GINECO-ARCAGY, endorsed by INCa. (Part 2: Systemic, intraperitoneal treatment, elderly patients, fertility preservation, follow-up). J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 48, 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, P.; Sehouli, J.; Lorusso, D.; Reuss, A.; Vergote, I.; Marth, C.; Kim, J.W.; Raspagliesi, F.; Lampe, B.; Aletti, G.; et al. A randomized trial of lymphadenectomy in patients with advanced ovarian neoplasms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.; Colombo, N.; Scambia, G.; Kim, B.G.; Oaknin, A.; Friedlander, M.; Lisyanskaya, A.; Floquet, A.; Leary, A.; Sonke, G.S.; et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Driel, W.J.; Koole, S.N.; Sikorska, K.; Schagen van Leeuwen, J.H.; Schreuder, H.W.; Hermans, R.H.; De Hingh, I.H.; Van Der Velden, J.; Arts, H.J.; Massuger, L.F.; et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).