Pulp–Dentin Tissue Healing Response: A Discussion of Current Biomedical Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

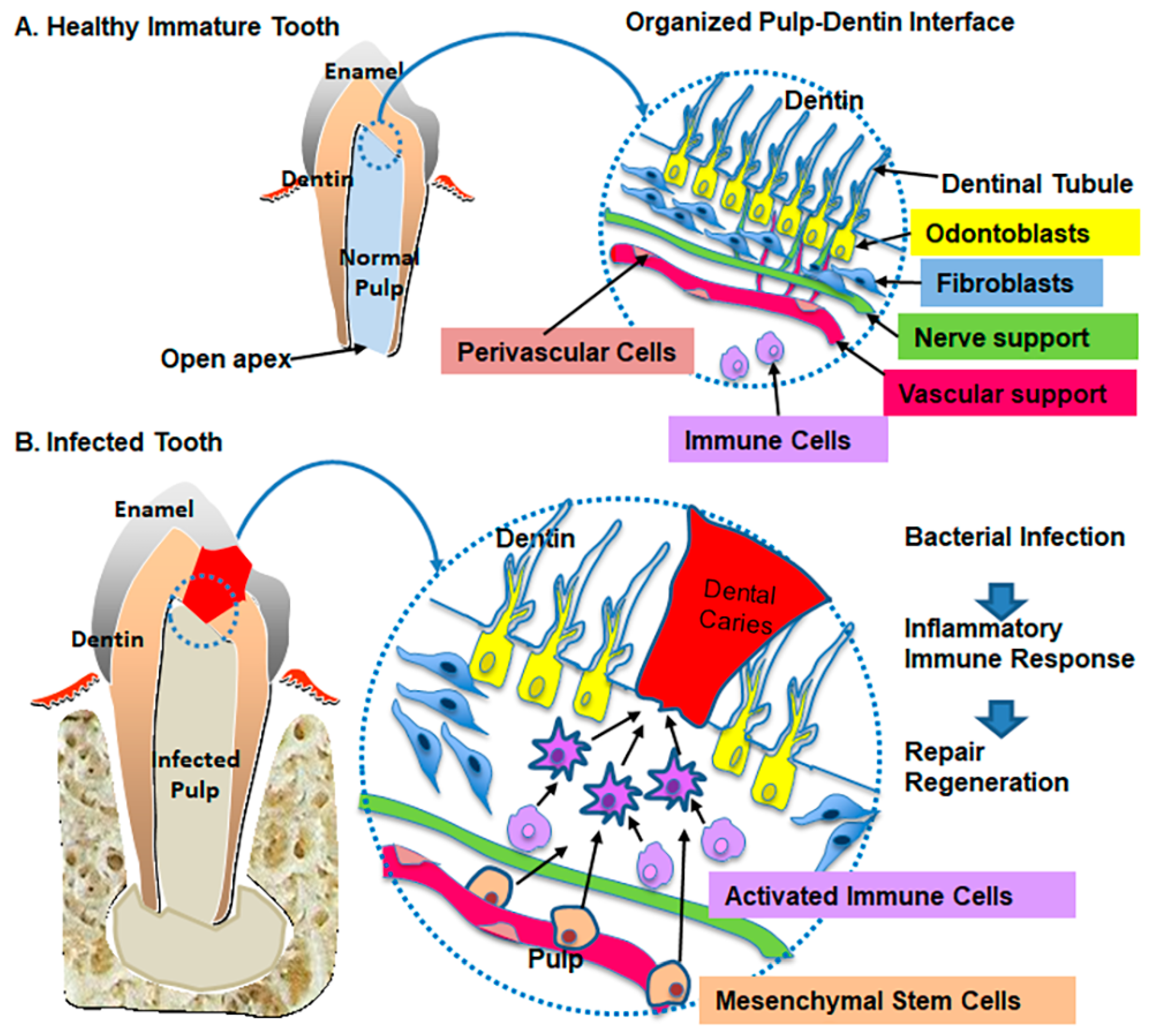

2. Characteristics of Pulp–Dentin Tissue

3. Biologic Defense Mechanism on Pulp–Dentin Tissue

4. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Response and Pulp–Dentin Tissue Response

5. Dental Apex and Periodontal–Tissue Response

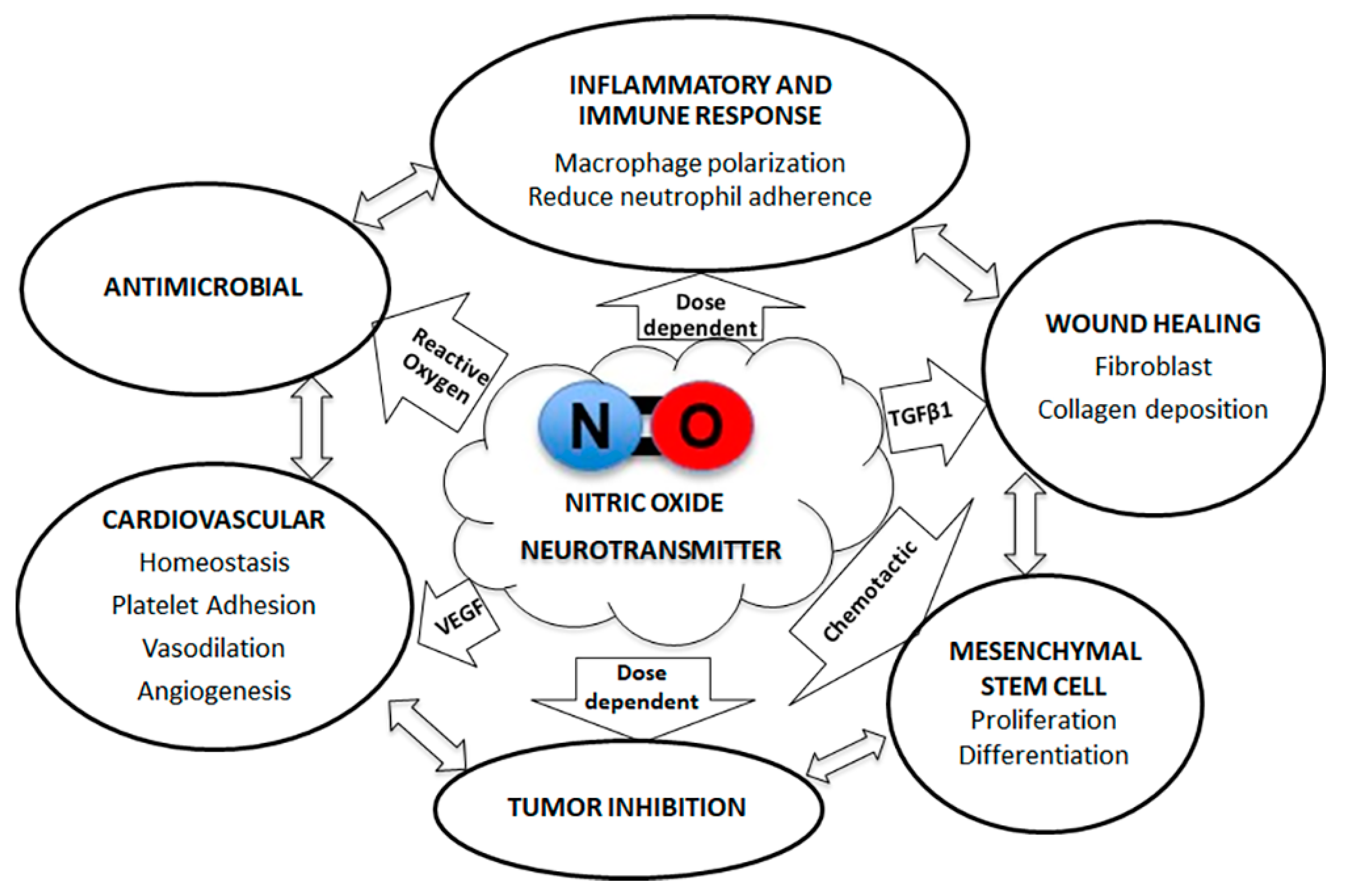

6. Nitric Oxide (NO) and Pulp–Dentin Tissue Response

7. Consideration of Potential Biomaterials for the Pulp–Dentin Tissue Revitalization

8. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robertson, D.P.; Keys, W.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Burns, R.; Smith, A.J. Management of severe acute dental infections. BMJ 2015, 350, h1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.L.; Houck, R.C. Dental Abscess. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2019; Volume 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, B.A.; Li, X.; Thorton-Evans, G. Oral Health Disparities as Determined by Selected Healthy People 2020 Oral Health Objectives for the United States, 2009–2010; NCHS Data Briefs; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, K.M.; Diogenes, A.; Teixeira, F.B. Treatment options: Biological basis of regenerative endodontic procedures. J. Endod. 2013, 39, S30–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostby, B.N. The role of the blood clot in endodontic therapy. An experimental histologic study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1961, 19, 324–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AAE. Regenerative Endodontics. In Endodontics Colleagues for Excellence; American Association of Endodontists: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, P.E.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Hargreaves, K.M. Regenerative endodontics: A review of current status and a call for action. J. Endod. 2007, 33, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranjpe, A.K. Are Regenerative Endodontic Procedures Working? Available online: https://www.aae.org/specialty/2019/09/30/are-regenerative-endodontic-procedures-working/# (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Reynolds, K.; Johnson, J.D.; Cohenca, N. Pulp revascularization of necrotic bilateral bicuspids using a modified novel technique to eliminate potential coronal discolouration: A case report. Int. Endod. J. 2009, 42, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.T.; Abbott, P.V.; McGinley, P. The effects of Ledermix paste on discolouration of immature teeth. Int. Endod. J. 2000, 33, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabbagh, B.; Alvaro, E.; Vu, D.D.; Rizkallah, J.; Schwartz, S. Clinical complications in the revascularization of immature necrotic permanent teeth. Pediatr. Dent. 2012, 34, 414–417. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen, J.O.; Farik, B.; Munksgaard, E.C. Long-term calcium hydroxide as a root canal dressing may increase risk of root fracture. Dent. Traumatol. 2002, 18, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, B.; Murray, P.E.; Namerow, K. The effect of calcium hydroxide root filling on dentin fracture strength. Dent. Traumatol. 2007, 23, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassen, G.H.; Chu, T.M.; Eckert, G.; Platt, J.A. Effect of medicaments used in endodontic regeneration technique on the chemical structure of human immature radicular dentin: An in vitro study. J. Endod. 2013, 39, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvek, M. Prognosis of luxated non-vital maxillary incisors treated with calcium hydroxide and filled with gutta-percha. A retrospective clinical study. Endod. Dent. Traumatol. 1992, 8, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Thibodeau, B.; Trope, M.; Lin, L.M.; Huang, G.T. Histologic characterization of regenerated tissues in canal space after the revitalization/revascularization procedure of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, E.; Jong, G.; Partridge, N.; Rosenberg, P.A.; Lin, L.M. Histologic observation of a human immature permanent tooth with irreversible pulpitis after revascularization/regeneration procedure. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 1293–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrat, A.; Homayounfar, N.; Oloomi, K. Drawbacks and unfavorable outcomes of regenerative endodontic treatments of necrotic immature teeth: A literature review and report of a case. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Chen, K.L.; Chen, C.A.; Tayebaty, F.; Rosenberg, P.A.; Lin, L.M. Responses of immature permanent teeth with infected necrotic pulp tissue and apical periodontitis/abscess to revascularization procedures. Int. Endod. J. 2012, 45, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.T. Dental pulp and dentin tissue engineering and regeneration: Advancement and challenge. Front. Biosci. Elite Ed. 2011, 3, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, M.T.; Valera, M.C.; Nakashima, M.; Nor, J.E.; Bottino, M.C. Tissue-engineering-based strategies for regenerative endodontics. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombouts, C.; Giraud, T.; Jeanneau, C.; About, I. Pulp Vascularization during Tooth Development, Regeneration, and Therapy. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmalz, G.; Smith, A.J. Pulp development, repair, and regeneration: Challenges of the transition from traditional dentistry to biologically based therapies. J. Endod. 2014, 40, S2–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.J.; Kim, S.G.; Zhou, J.; Ye, L.; Cho, S.; Suzuki, T.; Fu, S.Y.; Yang, R.; Zhou, X. Regenerative endodontics: Barriers and strategies for clinical translation. Dent. Clin. 2012, 56, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.T.; Gronthos, S.; Shi, S. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental tissues vs. those from other sources: Their biology and role in regenerative medicine. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, R.; Vacanti, J.P. Tissue engineering. Science 1993, 260, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galler, K.M.; D’Souza, R.N. Tissue engineering approaches for regenerative dentistry. Regen. Med. 2011, 6, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, S.; Can, A.; Arican, M.; Embree, M.C.; Mao, J.J. Characterization of dental pulp defect and repair in a canine model. Am. J. Dent. 2011, 24, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veerayutthwilai, O.; Byers, M.R.; Pham, T.T.; Darveau, R.P.; Dale, B.A. Differential regulation of immune responses by odontoblasts. Oral. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007, 22, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farges, J.C.; Alliot-Licht, B.; Renard, E.; Ducret, M.; Gaudin, A.; Smith, A.J.; Cooper, P.R. Dental Pulp Defence and Repair Mechanisms in Dental Caries. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 230251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jontell, M.; Gunraj, M.N.; Bergenholtz, G. Immunocompetent cells in the normal dental pulp. J. Dent. Res. 1987, 66, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M.; Farges, J.C.; Lacerda-Pinheiro, S.; Six, N.; Jegat, N.; Decup, F.; Septier, D.; Carrouel, F.; Durand, S.; Chaussain-Miller, C.; et al. Inflammatory and immunological aspects of dental pulp repair. Pharmacol. Res. 2008, 58, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eming, S.A.; Krieg, T.; Davidson, J.M. Inflammation in wound repair: Molecular and cellular mechanisms. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Cate, A.R. The role of epithelium in the development, structure and function of the tissues of tooth support. Oral Dis. 1996, 2, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricucci, D.; Siqueira, J.F.; Loghin, S.; Lin, L.M. Pulp and apical tissue response to deep caries in immature teeth: A histologic and histobacteriologic study. J. Dent. 2017, 56, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.T.; Sonoyama, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Shi, S. The hidden treasure in apical papilla: The potential role in pulp/dentin regeneration and bioroot engineering. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, K.H.; Song, J.S.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.S.; Jeon, M.; Kim, S.O.; Lee, J.H. Cytokine Expression of Stem Cells Originating from the Apical Complex and Coronal Pulp of Immature Teeth. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tang, L.; Jin, F.; Liu, X.H.; Yu, J.H.; Wu, J.J.; Yang, Z.H.; Wang, Y.X.; Duan, Y.Z.; Jin, Y. The apical region of developing tooth root constitutes a complex and maintains the ability to generate root and periodontium-like tissues. J. Periodontal Res. 2009, 44, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Meligy, O.A.; Avery, D.R. Comparison of mineral trioxide aggregate and calcium hydroxide as pulpotomy agents in young permanent teeth (apexogenesis). Pediatr. Dent. 2006, 28, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.S.; Shetty, D.C.; Urs, A.B.; Nainani, P. Role of inflammation in developmental odontogenic pathosis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2016, 20, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Wang, H.L.; Glickman, G.N. The influence of endodontic treatment upon periodontal wound healing. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1997, 24, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, G.W.; Bresnen, D.; Jenkins, E.; Mullen, N. Dental Abscess in Pediatric Patients: A Marker of Neglect. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2018, 34, 774–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, B.; Trope, M. Pulp revascularization of a necrotic infected immature permanent tooth: Case report and review of the literature. Pediatr. Dent. 2007, 29, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jeeruphan, T.; Jantarat, J.; Yanpiset, K.; Suwannapan, L.; Khewsawai, P.; Hargreaves, K.M. Mahidol study 1: Comparison of radiographic and survival outcomes of immature teeth treated with either regenerative endodontic or apexification methods: A retrospective study. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Godoy, F.; Murray, P.E. Recommendations for using regenerative endodontic procedures in permanent immature traumatized teeth. Dent. Traumatol. 2012, 28, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nardo Di Maio, F.; Lohinai, Z.; D’Arcangelo, C.; De Fazio, P.E.; Speranza, L.; De Lutiis, M.A.; Patruno, A.; Grilli, A.; Felaco, M. Nitric oxide synthase in healthy and inflamed human dental pulp. J. Dent. Res. 2004, 83, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncada, S.; Higgs, A. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 2002–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, S.H.; Flacher, V.; Roméas, A.; Carrouel, F.; Colomb, E.; Vincent, C.; Magloire, H.; Couble, M.L.; Bleicher, F.; Staquet, M.J.; et al. Lipoteichoic acid increases TLR and functional chemokine expression while reducing dentin formation in in vitro differentiated human odontoblasts. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 2880–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, A.K. The control of T cell activation vs. tolerance. Autoimmun. Rev. 2003, 2, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, G.J.; Inaba, K.; Robbiani, D.F.; Steinman, R.M.; Muller, W.A. Differentiation of phagocytic monocytes into lymph node dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity 1999, 11, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnani, S. Th1/Th2 cells. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 1999, 5, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, T.J.; DiPietro, L.A. Inflammation and wound healing: The role of the macrophage. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2011, 13, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, N.; Wongyaofa, I.; Suzuki, N.; Kawanishi, H.N.; Suda, H. NK and NKT cells in the rat dental pulp tissues. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2006, 102, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayry, J.; Lacroix-Desmazes, S.; Kazatchkine, M.D.; Hermine, O.; Tough, D.F.; Kaveri, S.V. Modulation of dendritic cell maturation and function by B lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubes, P.; Suzuki, M.; Granger, D.N. Nitric oxide: An endogenous modulator of leukocyte adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 4651–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, M.; Njeh, A.; Uzunoglu, E. Is Pulp Inflammation a Prerequisite for Pulp Healing and Regeneration? Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 347649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, C. CXCR4: Chemokine receptor extraordinaire. Immunol. Rev. 2000, 177, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Wang, Z.; Luo, Z.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Smith, A.J.; Cooper, P.R. LPS promote the odontoblastic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells via MAPK signaling pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.J.; Banisadr, G.; Bhattacharyya, B.J. CXCR4 signaling in the regulation of stem cell migration and development. J. Neuroimmunol. 2008, 198, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, C.M.; An, S.; Cheng, Q.; Huang, Y.F.; Wang, Y.T.; Gou, Y.C.; Xiao, L.; Yu, W.J.; Wang, J. Immunomodulatory properties of dental tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Oral Dis. 2014, 20, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velnar, T.; Bailey, T.; Smrkolj, V. The wound healing process: An overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Int. Med. Res. 2009, 37, 1528–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, M.; Akamine, A. The application of tissue engineering to regeneration of pulp and dentin in endodontics. J. Endod. 2005, 31, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, N.; Corallo, C.; Chan, B.M.; Ferrari, M.; Gerami-Naini, B. Multipotent Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells: A Literature Review. Stem Cell. Rev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Pandya, M.; Rufaihah, A.J.; Rosa, V.; Tong, H.J.; Seliktar, D.; Toh, W.S. Modulation of Dental Pulp Stem Cell Odontogenesis in a Tunable PEG-Fibrinogen Hydrogel System. Stem Cells Int. 2015, 2015, 525367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teti, G.; Salvatore, V.; Focaroli, S.; Durante, S.; Mazzotti, A.; Dicarlo, M.; Mattioli-Belmonte, M.; Orsini, G. In vitro osteogenic and odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells seeded on carboxymethyl cellulose-hydroxyapatite hybrid hydrogel. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.R.; Lee, D.H.; Chung, P.H.; Yang, H.C. Distinct differentiation properties of human dental pulp cells on collagen, gelatin, and chitosan scaffolds. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2009, 108, e94–e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, A.; Rychkov, G.; Shi, S.; Koblar, S.A.; Gronthos, S. Adult human dental pulp stem cells differentiate toward functionally active neurons under appropriate environmental cues. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Aquino, R.; Graziano, A.; Sampaolesi, M.; Laino, G.; Pirozzi, G.; De Rosa, A.; Papaccio, G. Human postnatal dental pulp cells co-differentiate into osteoblasts and endotheliocytes: A pivotal synergy leading to adult bone tissue formation. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts-Clark, D.J.; Smith, A.J. Angiogenic growth factors in human dentine matrix. Arch. Oral Biol. 2000, 45, 1013–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, S.; El-Battari, A.; Dejou, J.; About, I. Role of injured endothelial cells in the recruitment of human pulp cells. Arch. Oral Biol. 2005, 50, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Subbarao, R.B.; Rho, G.J. Human mesenchymal stem cells—Current trends and future prospective. Biosci. Rep. 2015, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.J.; Kaufman, M.H. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature 1981, 292, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, G.; Yoo, J.J.; De Coppi, P.; Siddiqui, M.M.; Schuch, G.; Pohl, H.G.; Fuhr, J.; Perin, L.; Soker, S.; Atala, A. Propagation, expansion, and multilineage differentiation of human somatic stem cells from dermal progenitors. Stem Cells Dev. 2005, 14, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yianni, V.; Sharpe, P.T. Perivascular-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Dent. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomar, G.B.; Srivastava, R.K.; Gupta, N.; Barhanpurkar, A.P.; Pote, S.T.; Jhaveri, H.M.; Mishra, G.C.; Wani, M.R. Human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells are superior to bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for cell therapy in regenerative medicine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 393, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, P.T. Dental mesenchymal stem cells. Development 2016, 143, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Mantesso, A.; De Bari, C.; Nishiyama, A.; Sharpe, P.T. Dual origin of mesenchymal stem cells contributing to organ growth and repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6503–6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, J.L.; Smith, A.A.; Helms, J.A. Wnt signaling and injury repair. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a008078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaza, T.; Kentaro, A.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Gronthos, S.; Wang, S.; Shi, S. Immunomodulatory properties of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2010, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Z.; Su, W.R.; Shi, S.H.; Wilder-Smith, P.; Xiang, A.P.; Wong, A.; Nguyen, A.L.; Kwon, C.W.; Le, A.D. Human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells elicit polarization of m2 macrophages and enhance cutaneous wound healing. Stem Cells 2010, 28, 1856–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, A.I.; Correa, D. The MSC: An injury drugstore. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 9, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chen, M.Y.; Ricucci, D.; Rosenberg, P.A. Guided tissue regeneration in periapical surgery. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, R.C. The role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J. Periodontal Res. 1991, 26, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stashenko, P.; Teles, R.; D’Souza, R. Periapical inflammatory responses and their modulation. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1998, 9, 498–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinaia, B.M.; Chogle, S.M.; Kinaia, A.M.; Goodis, H.E. Regenerative therapy: A periodontal-endodontic perspective. Dent. Clin. 2012, 56, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashutski, J.D.; Wang, H.L. Periodontal and endodontic regeneration. J. Endod. 2009, 35, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Torres, A.; Sanchez-Garces, M.A.; Gay-Escoda, C. Materials and prognostic factors of bone regeneration in periapical surgery: A systematic review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2014, 19, e419–e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.M.; Rodriguez, A.; Chang, D.T. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin. Immunol. 2008, 20, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morand, D.N.; Davideau, J.L.; Clauss, F.; Jessel, N.; Tenenbaum, H.; Huck, O. Cytokines during periodontal wound healing: Potential application for new therapeutic approach. Oral Dis. 2017, 23, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, M.B.; Barbul, A. Role of nitric oxide in wound repair. Am. J. Surg. 2002, 183, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.W.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Nitric oxide release: Part II. Therapeutic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3742–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumura, D.; Kashiwagi, S.; Jain, R.K. The role of nitric oxide in tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Nulend, J.; van Oers, R.F.; Bakker, A.D.; Bacabac, R.G. Nitric oxide signaling in mechanical adaptation of bone. Osteoporos. Int. 2014, 25, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, F.; Tang, Y.; Wang, T.; Feng, T.; Song, J.; Li, P.; Huang, W. Nitric Oxide-Releasing Polymeric Materials for Antimicrobial Applications: A Review. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhari, S.K.; Chaudhary, M.; Bagde, S.; Gadbail, A.R.; Joshi, V. Nitric oxide and cancer: A review. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armour, K.E.; Armour, K.J.; Gallagher, M.E.; Godecke, A.; Helfrich, M.H.; Reid, D.M.; Ralston, S.H. Defective bone formation and anabolic response to exogenous estrogen in mice with targeted disruption of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonoda, S.; Mei, Y.F.; Atsuta, I.; Danjo, A.; Yamaza, H.; Hama, S.; Nishida, K.; Tang, R.; Kyumoto-Nakamura, Y.; Uehara, N.; et al. Exogenous nitric oxide stimulates the odontogenic differentiation of rat dental pulp stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uehara, E.U.; Shida Bde, S.; de Brito, C.A. Role of nitric oxide in immune responses against viruses: Beyond microbicidal activity. Inflamm. Res. 2015, 64, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Zhang, R.; Geng, S.; Peng, L.; Jayaraman, P.; Chen, C.; Xu, F.; Yang, J.; Li, Q.; Zheng, H.; et al. Myeloid cell-derived inducible nitric oxide synthase suppresses M1 macrophage polarization. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Tateya, S.; Cheng, A.M.; Rizzo-DeLeon, N.; Wang, N.F.; Handa, P.; Wilson, C.L.; Clowes, A.W.; Sweet, I.R.; Bomsztyk, K.; et al. M2 Macrophage Polarization Mediates Anti-inflammatory Effects of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Signaling. Diabetes 2015, 64, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, L.; Moradi-Bidhendi, N.; Becherini, L.; Martineti, V.; MacIntyre, I. The biphasic effects of nitric oxide in primary rat osteoblasts are cGMP dependent. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 274, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riancho, J.A.; Salas, E.; Zarrabeitia, M.T.; Olmos, J.M.; Amado, J.A.; Fernandez-Luna, J.L.; Gonzalez-Macias, J. Expression and functional role of nitric oxide synthase in osteoblast-like cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1995, 10, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, H.; Schall, N.; Pilz, R.B. Nitric oxide and cyclic GMP functions in bone. Nitric Oxide 2018, 76, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meesters, D.M.; Neubert, S.; Wijnands, K.A.P.; Heyer, F.L.; Zeiter, S.; Ito, K.; Brink, P.R.G.; Poeze, M. Deficiency of inducible and endothelial nitric oxide synthase results in diminished bone formation and delayed union and nonunion development. Bone 2016, 83, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, J.S.; Moore, A.N.; Hartgerink, J.D.; D’Souza, R.N. Scaffolds to control inflammation and facilitate dental pulp regeneration. J. Endod. 2014, 40, S6–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottino, M.C.; Pankajakshan, D.; Nor, J.E. Advanced Scaffolds for Dental Pulp and Periodontal Regeneration. Dent. Clin. 2017, 61, 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupte, M.J.; Ma, P.X. Nanofibrous scaffolds for dental and craniofacial applications. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmalz, G.; Galler, K.M. Biocompatibility of biomaterials—Lessons learned and considerations for the design of novel materials. Dent. Mater. Off. Publ. Acad. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, K.M.; Hartgerink, J.D.; Cavender, A.C.; Schmalz, G.; D’Souza, R.N. A customized self-assembling peptide hydrogel for dental pulp tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part A 2012, 18, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, K.M.; D’Souza, R.N.; Hartgerink, J.D.; Schmalz, G. Scaffolds for dental pulp tissue engineering. Adv. Dent. Res. 2011, 23, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, K.M.; Brandl, F.P.; Kirchhof, S.; Widbiller, M.; Eidt, A.; Buchalla, W.; Göpferich, A.; Schmalz, G. Suitability of Different Natural and Synthetic Biomaterials for Dental Pulp Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. Part A 2018, 24, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, B.; Ahuja, N.; Ma, C.; Liu, X. Injectable scaffolds: Preparation and application in dental and craniofacial regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. A Rev. J. 2017, 111, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zein, N.; Harmouch, E.; Lutz, J.-C.; Fernandez De Grado, G.; Kuchler-Bopp, S.; Clauss, F.; Offner, D.; Hua, G.; Benkirane-Jessel, N.; Fioretti, F. Polymer-Based Instructive Scaffolds for Endodontic Regeneration. Materials 2019, 12, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, A.; Zein, N.; Harmouch, E.; Hafdi, B.; Bornert, F.; Offner, D.; Clauss, F.; Fioretti, F.; Huck, O.; Benkirane-Jessel, N.; et al. Application of Chitosan in Bone and Dental Engineering. Molecules 2019, 24, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, D.J.; Powell, C.; Piana, J.; Rutherford, B. Engineering dental pulp-like tissue in vitro. Biotechnol. Prog. 1996, 12, 865–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohl, K.S.; Shon, J.; Rutherford, B.; Mooney, D.J. Role of synthetic extracellular matrix in development of engineered dental pulp. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 1998, 9, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, R.S.; Alsanea, R.; Fayad, M.I.; Johnson, B.R.; Wenckus, C.S.; Hao, J.; John, A.S.; George, A. In vivo generation of dental pulp-like tissue by using dental pulp stem cells, a collagen scaffold, and dentin matrix protein 1 after subcutaneous transplantation in mice. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, F.; Walboomers, X.F.; Bian, Z.; Fan, M.; Jansen, J.A. The performance of dental pulp stem cells on nanofibrous PCL/gelatin/nHA scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2010, 93, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ma, H.; Jin, X.; Hu, J.; Liu, X.; Ni, L.; Ma, P.X. The effect of scaffold architecture on odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7822–7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, J.; Che, H.; Ning, F.; Zhang, X.; Xun, W.; Huo, N.; Tang, L.; et al. Natural mineralized scaffolds promote the dentinogenic potential of dental pulp stem cells via the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Tissue Eng. Part A 2012, 18, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkouch, A.; Zhang, Z.; Rouabhia, M. Engineering bone tissue using human dental pulp stem cells and an osteogenic collagen-hydroxyapatite-poly (L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) scaffold. J. Biomater. Appl. 2014, 28, 922–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, B.N.; Zeitlin, B.D.; Nör, J.E. A hydrogel scaffold that maintains viability and supports differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. Dent. Mater. Off. Publ. Acad. Dent. Mater. 2013, 29, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Han, G.; Pang, X.; Fan, M. Chitosan/collagen scaffold containing bone morphogenetic protein-7 DNA supports dental pulp stem cell differentiation in vitro and in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, M.; Horibe, H.; Iohara, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Osako, Y.; Takei, Y.; Nakata, K.; Motoyama, N.; Kurita, K.; Nakashima, M. The use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor induced mobilization for isolation of dental pulp stem cells with high regenerative potential. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 9036–9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iohara, K.; Murakami, M.; Takeuchi, N.; Osako, Y.; Ito, M.; Ishizaka, R.; Utunomiya, S.; Nakamura, H.; Matsushita, K.; Nakashima, M. A novel combinatorial therapy with pulp stem cells and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for total pulp regeneration. Stem cells Transl. Med. 2013, 2, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iohara, K.; Murakami, M.; Nakata, K.; Nakashima, M. Age-dependent decline in dental pulp regeneration after pulpectomy in dogs. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 52, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, M.M.; Dong, Z.; Kaneko, T.; Zhang, Z.; Miyazawa, M.; Shi, S.; Smith, A.J.; Nor, J.E. Dental pulp tissue engineering with stem cells from exfoliated deciduous teeth. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyac, B.R.; Chicatun, F.; Hoac, B.; Nelea, V.; Chaussain, C.; Nazhat, S.N.; McKee, M.D. Mineralization of dense collagen hydrogel scaffolds by human pulp cells. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, V.; Zhang, Z.; Grande, R.H.; Nor, J.E. Dental pulp tissue engineering in full-length human root canals. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 970–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronthos, S.; Mankani, M.; Brahim, J.; Robey, P.G.; Shi, S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13625–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, M.; Gronthos, S.; Zhao, M.; Lu, B.; Fisher, L.W.; Robey, P.G.; Shi, S. SHED: Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5807–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, K.M.; Cavender, A.; Yuwono, V.; Dong, H.; Shi, S.; Schmalz, G.; Hartgerink, J.D.; D’Souza, R.N. Self-assembling peptide amphiphile nanofibers as a scaffold for dental stem cells. Tissue Eng. Part A 2008, 14, 2051–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.T.; Yamaza, T.; Shea, L.D.; Djouad, F.; Kuhn, N.Z.; Tuan, R.S.; Shi, S. Stem/progenitor cell-mediated de novo regeneration of dental pulp with newly deposited continuous layer of dentin in an in vivo model. Tissue Eng. Part A 2010, 16, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galler, K.M.; Cavender, A.C.; Koeklue, U.; Suggs, L.J.; Schmalz, G.; D’Souza, R.N. Bioengineering of dental stem cells in a PEGylated fibrin gel. Regen. Med. 2011, 6, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobie, K.; Smith, G.; Sloan, A.J.; Smith, A.J. Effects of alginate hydrogels and TGF-beta 1 on human dental pulp repair in vitro. Connect. Tissue Res. 2002, 43, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishimatsu, H.; Kitamura, C.; Morotomi, T.; Tabata, Y.; Nishihara, T.; Chen, K.-K.; Terashita, M. Formation of dentinal bridge on surface of regenerated dental pulp in dentin defects by controlled release of fibroblast growth factor-2 from gelatin hydrogels. J. Endod. 2009, 35, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, K.; Sun, H.; Bradley, M.A.; Dupler, E.J.; Giannobile, W.V.; Ma, P.X. Novel antibacterial nanofibrous PLLA scaffolds. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2010, 146, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galler, K.M.; D’Souza, R.N.; Federlin, M.; Cavender, A.C.; Hartgerink, J.D.; Hecker, S.; Schmalz, G. Dentin conditioning codetermines cell fate in regenerative endodontics. J. Endod. 2011, 37, 1536–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottino, M.C.; Kamocki, K.; Yassen, G.H.; Platt, J.A.; Vail, M.M.; Ehrlich, Y.; Spolnik, K.J.; Gregory, R.L. Bioactive nanofibrous scaffolds for regenerative endodontics. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottino, M.C.; Yassen, G.H.; Platt, J.A.; Labban, N.; Windsor, L.J.; Spolnik, K.J.; Bressiani, A.H.A. A novel three-dimensional scaffold for regenerative endodontics: Materials and biological characterizations. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2015, 9, E116–E123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piva, E.; Silva, A.F.; Nor, J.E. Functionalized scaffolds to control dental pulp stem cell fate. J. Endod. 2014, 40, S33–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widbiller, M.; Driesen, R.B.; Eidt, A.; Lambrichts, I.; Hiller, K.A.; Buchalla, W.; Schmalz, G.; Galler, K.M. Cell Homing for Pulp Tissue Engineering with Endogenous Dentin Matrix Proteins. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, C.Y.; Nam, O.H.; Kim, M.; Lee, H.S.; Kaushik, S.N.; Cruz Walma, D.A.; Jun, H.W.; Cheon, K.; Choi, S.C. Effects of the nitric oxide releasing biomimetic nanomatrix gel on pulp-dentin regeneration: Pilot study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, S.N.; Kim, B.; Walma, A.M.; Choi, S.C.; Wu, H.; Mao, J.J.; Jun, H.W.; Cheon, K. Biomimetic microenvironments for regenerative endodontics. Biomater. Res. 2016, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stem Cells | Scaffold | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulp fibroblasts | PGA, collagen I, alginate | Pulp-like tissue after 45 to 60 days on PGA | [117,118] |

| Human DPSCs | Col Type I with CP and DMP-1 | New pulp-like tissue formation and organization | [119] |

| Collagens I and III, chitosan, gelatin | Adhesion and proliferation | [66] | |

| NF-PCL/gelatin/nHA | DPSC differentiation toward an odontoblast-like cells in vitro and in vivo | [120] | |

| NF-PLLA | Attachment, proliferation, and differentiation of human DPSCs | [121] | |

| Self-assembling MDP | Pulp-like tissue formation | [111] | |

| DDM-PLGA/Co-Cs-HA | Potential as attractive scaffolds for odontogenic differentiation | [122] | |

| 3D Col/HA/PLCL | DPSC Differentiation and proliferation | [123] | |

| Self-assembling peptide (PuramatrixTM) | DPSC survival, proliferation, and differentiation | [124] | |

| Porous chitosan/Col | Release of BMP-7 gene; DPSC differentiation into odontoblast-like cells in vitro and in vivo | [125] | |

| Dog mobilized DPSCs | Col with G-CSF | Ectopic model, pulp-like tissue regeneration | [126] |

| Complete pulp-like and dentin-like tissue regeneration | [127] | ||

| Orthotopic model; Less volume of regenerated pulp-like tissue in aged dogs compared with that in young dogs | [128] | ||

| SHED | PLLA | Pulp-like tissue formation | [129] |

| 3dimension dense Col | Odontogenic cell differentiation and mineralization | [130] | |

| Peptide(PuramatrixTM) with rhCol type I | SHED injected into full-length human root canals differentiate into functional odontoblasts | [131] | |

| DPSCs & SHED | HA/TCP | Generation of dentin or bone (SHED) and dentin-pulp-like complexes (DPSC) | [132,133] |

| PA self-assembling NF | Easy to handle; introduced into small defects; cell proliferation | [134] | |

| DPSCs & SCAPs | Poly-D,L-lactide/glycolide | Pulp-like tissue formation with vascularity and dentin-like structure | [135] |

| DPSCs, SCAPs, PDLSCs, and BMSSCs | PEGylated fibrin gel | All types of dental stem cells proliferated; excellent biocompatibility; insertion into small defects | [136] |

| No Stem Cells | Alginate with TGF-β1 | Release of TGF-β1; odontoblast-like cell differentiation | [137] |

| Gelatin incorporation of FGF-2 | Release of FGF-2; Induces the invasion of dental pulp cells and vessels | [138] | |

| NF-PLGA/PLLA scaffolds with DOXY | Release of DOXY; inhibition of bacterial growth for a prolonged duration | [139] | |

| GF–laden peptide with VEGF, TGFβ-1, and FGF-2 | Release of VEGF, TGF-β1, and FGF2; odontoblast-like cell differentiation; pulp-like tissue formation | [140] | |

| NF PDS II-with MET and CIP | Release MET or CIP; antimicrobial activity against Ef and Pg | [141] | |

| NF PDS II-HNTs | Potential in the development of a bioactive scaffold for regenerative endodontics | [142] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shah, D.; Lynd, T.; Ho, D.; Chen, J.; Vines, J.; Jung, H.-D.; Kim, J.-H.; Zhang, P.; Wu, H.; Jun, H.-W.; et al. Pulp–Dentin Tissue Healing Response: A Discussion of Current Biomedical Approaches. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020434

Shah D, Lynd T, Ho D, Chen J, Vines J, Jung H-D, Kim J-H, Zhang P, Wu H, Jun H-W, et al. Pulp–Dentin Tissue Healing Response: A Discussion of Current Biomedical Approaches. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(2):434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020434

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Dishant, Tyler Lynd, Donald Ho, Jun Chen, Jeremy Vines, Hwi-Dong Jung, Ji-Hun Kim, Ping Zhang, Hui Wu, Ho-Wook Jun, and et al. 2020. "Pulp–Dentin Tissue Healing Response: A Discussion of Current Biomedical Approaches" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 2: 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020434

APA StyleShah, D., Lynd, T., Ho, D., Chen, J., Vines, J., Jung, H.-D., Kim, J.-H., Zhang, P., Wu, H., Jun, H.-W., & Cheon, K. (2020). Pulp–Dentin Tissue Healing Response: A Discussion of Current Biomedical Approaches. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(2), 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020434