Oral Lichen Planus and Dental Implants: Protocol and Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

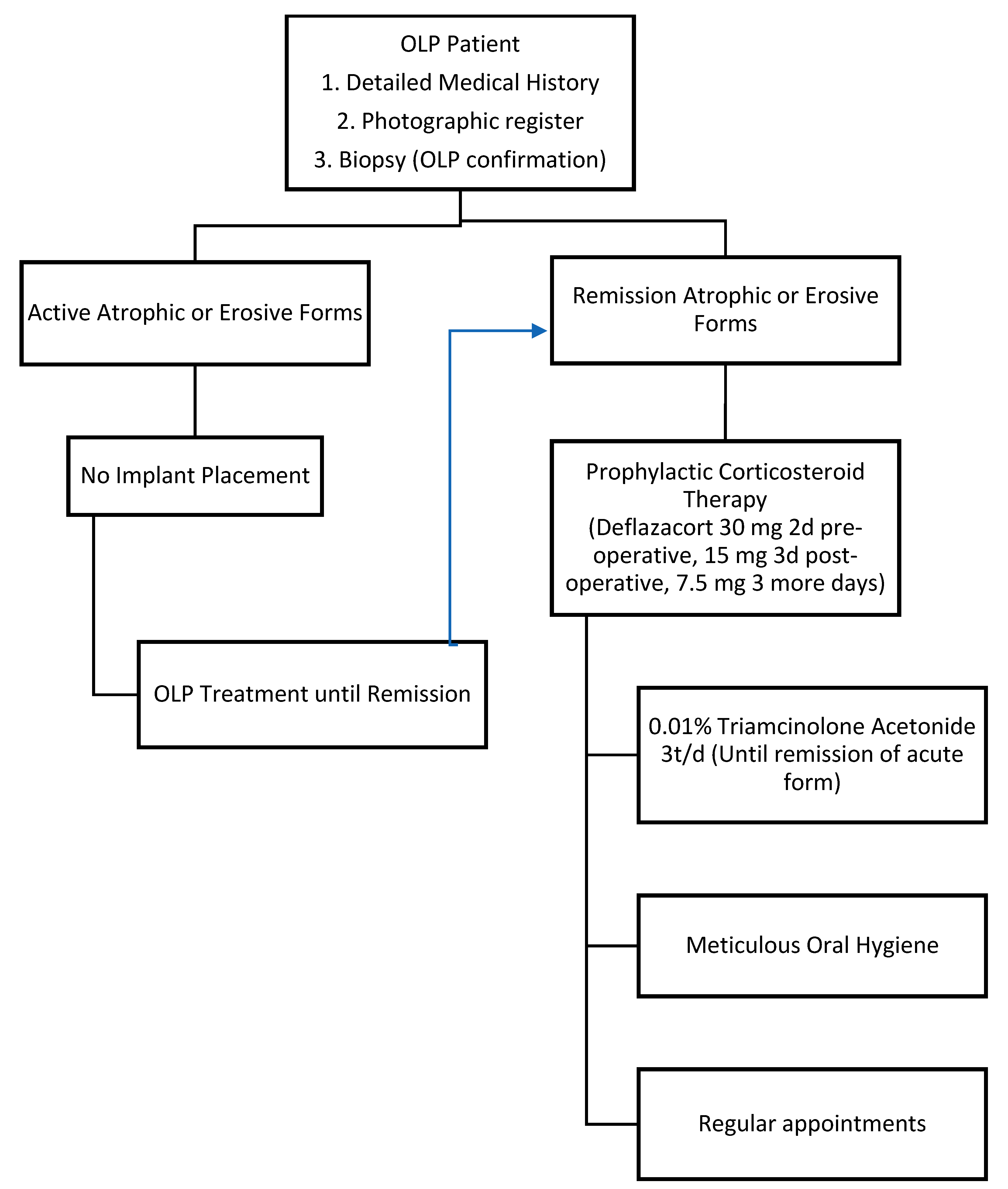

2. Experimental Section

Statistical Analysis

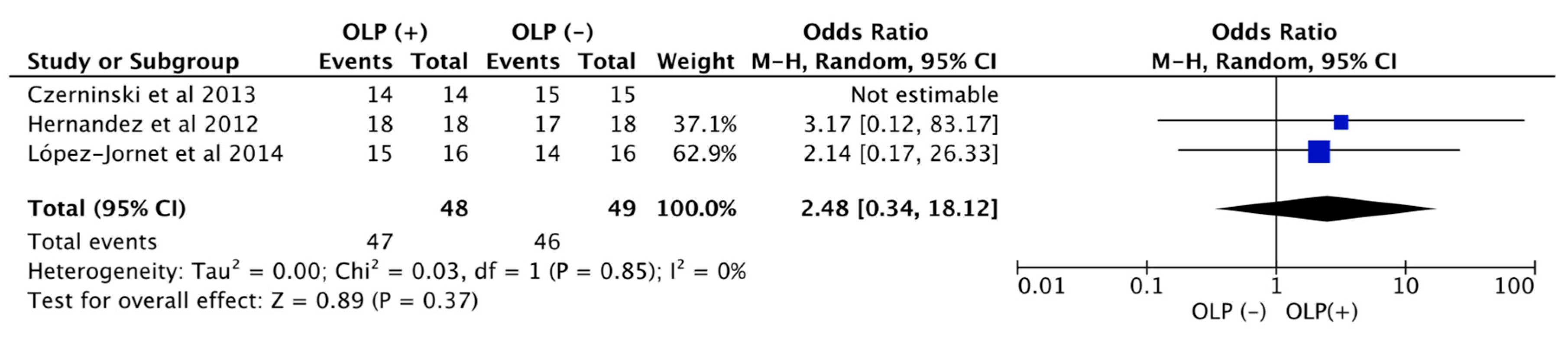

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strietzel, F.P.; Schmidt-Westhausen, A.M.; Neumann, K.; Reichart, P.A.; Jackowski, J. Implants in patients with oral manifestations of autoimmune or muco-cutaneous diseases—A systematic review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2019, 24, e217–e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghbari, S.M.H.; Abushouk, A.I.; Attia, A.; Elmaraezy, A.; Menshawy, A.; Ahmed, M.S.; Elsaadany, B.A.; Ahmed, E.M. Malignant transformation of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: A meta-analysis of 20095 patient data. Oral Oncol. 2017, 68, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichart, P.A.; Schmidt-Westhausen, A.M.; Khongkhunthian, P.; Strietzel, F.P. Dental implants in patients with oral mucosal diseases—A systematic review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roopashree, M.R.; Gondhalekar, R.V.; Shashikanth, M.C.; George, J.; Thippeswamy, S.H.; Shukla, A. Pathogenesis of oral lichen planus—A review. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2010, 39, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axell, T.; Rundquist, L. Oral lichen planus—A demographic study. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1987, 15, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraschini, V.; Poubel, L.D.C.; Ferreira, V.; Moraschini, V. Evaluation of survival and success rates of dental implants reported in longitudinal studies with a follow-up period of at least 10 years: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 44, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson, B.E.; Heimisdottir, K. Dental implants – are they better than natural teeth? Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 126 (Suppl. 1), 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherlone, E.F.; Capparé, P.; Tecco, S.; Polizzi, E.; Pantaleo, G.; Gastaldi, G.; Grusovin, M.G. A Prospective Longitudinal Study on Implant Prosthetic Rehabilitation in Controlled HIV-Positive Patients with 1-Year Follow-Up: The Role of CD4+ Level, Smoking Habits, and Oral Hygiene. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2016, 18, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebell, M.H.; Siwek, J.; Weiss, B.D.; Woolf, S.H.; Susman, J.; Ewigman, B.; Bowman, M. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): A patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. Am. Fam. Physician 2004, 69, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Thomsen, P.; Ericson, L.E.; Sennerby, L.; Lekholm, U. Histopathologic Observations on Late Oral Implant Failures. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2000, 2, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, S.J.; Camisa, C.; Morgan, M. Implant retained overdentures for two patients with severe lichen planus: A clinical report. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 89, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oczakir, C.; Balmer, S.; Mericske-Stern, R. Implant-prosthodontic treatment for special care patients: A case series study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2005, 18, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reichart, P.A. Oral lichen planus and dental implants. Report of 3 cases. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 35, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerninski, R.; Kaplan, I.; Almoznino, G.; Maly, A.; Regev, E. Oral squamous cell carcinoma around dental implants. Quintessence Int. 2006, 37, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gallego, L.; Junquera, L.; Baladrón, J.; Villarreal, P. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Associated with Symphyseal Dental Implants: An unusual case report. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2008, 139, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerninski, R.; Eliezer, M.; Wilensky, A.; Soskolne, A. Oral Lichen Planus and Dental Implants—A Retrospective Study. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2011, 15, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, E.; Spink, M.J.; Messina, A.M. Peri-implant Primary Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Case Report With 5 Years’ Follow-Up. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 71, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moergel, M.; Karbach, J.; Kunkel, M.; Wagner, W. Oral squamous cell carcinoma in the vicinity of dental implants. Clin. Oral Investig. 2014, 18, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jornet, P.; Camacho-Alonso, F.; Sánchez-Siles, M. Dental Implants in Patients with Oral Lichen Planus: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2012, 16, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiser, V.; Naaj, I.A.-E.; Shlomi, B.; Fliss, D.M.; Kaplan, I. Primary Oral Malignancy Imitating Peri-Implantitis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboushelib, M.N.; Elsafi, M.H. Clinical Management Protocol for Dental Implants Inserted in Patients with Active Lichen Planus. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 26, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anitua, E.; Piñas, L.; Escuer-Artero, V.; Fernández, R.; Khraisat, A. Short dental implants in patients with oral lichen planus: A long-term follow-up. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 56, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Y. Implant-Retained Overdenture for a Patient with Severe Lichen Planus: A Case Report with 3 Years’ Follow-Up and a Systematic Review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 77, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, G.; Arriba, L.; López-Pintor, R.-M.; Torres, J.; De Vicente, J.-C. Implant treatment in patients with oral lichen planus: A prospective-controlled study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2012, 23, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankapure, P.K.; Humbe, J.G.; Mandale, M.S.; Bhavthankar, J.D. Clinical profile of 108 cases of oral lichen planus. J. Oral Sci. 2016, 58, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.B.; Kumar, S.K.S.; Zain, R.B. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid reactions: Etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, management and malignant transformation. J. Oral Sci. 2007, 49, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashdan, M.S.; Cirillo, N.; McCullough, M. Oral lichen planus: A literature review and update. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2016, 308, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Meij, E.H.; Van Der Waal, I. Lack of clinicopathologic correlation in the diagnosis of oral lichen planus based on the presently available diagnostic criteria and suggestions for modifications. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2003, 32, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmara, F.; Khayamzadeh, M.; Shabankare, G. Applying dental implant therapy in patients with oral lichen planus: A review of literature. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2020, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Perez, O.; Luquin, S.; Garcia-Estrada, J.; Ramos-Remus, C. Deflazacort: A glucocorticoid with few metabolic adverse effects but important immunosuppressive activity. Adv. Ther. 2007, 24, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gherlone, E.F.; Capparé, P.; Tecco, S.; Polizzi, E.; Pantaleo, G.; Gastaldi, G.; Grusovin, M.G. Implant Prosthetic Rehabilitation in Controlled HIV-Positive Patients: A Prospective Longitudinal Study with 1-Year Follow-Up. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2016, 18, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jané-Salas, E.; López, J.L.; Roselló-Llabrés, X.; Rodríguez-Argueta, O.-F.; Küstner, E.C. Relationship between oral cancer and implants: Clinical cases and systematic literature review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2012, 17, e23–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diz, P.; Scully, C.; Sanz, M. Dental implants in the medically compromised patient. J. Dent. 2013, 41, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrcanovic, B.; Cruz, A.F.; Trindade, R.; Gomez, R.S. Dental Implants in Patients with Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2020, 56, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Article | Study Design | Sort | Nº Patients | Gender | Age | OLP Type | OLP Location | OLP Duration (Years) | OLP Biopsy | N° Implants | Protheses | Survival Rate | Follow-up (Months) | OSCC | OLP Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esposito et al. (2003) | Cr | 2 | 1 | F | 69 | Erosive | - | - | Ni | 2 | Overdenture | - | 32/60 | - | |

| Esposito et al. (2003) | Cr | 2 | 2 | F | 72 78 | Erosive | Buccal mucosa Gingiva | 16 | Yes | 4 | Overdenture | 100% | 21 | - | |

| Öczakir et al. (2005) | Cr | 2 | 1 | F | 74 | - | - | - | Ni | 4 | Fixed complete | 100% | 72 | ||

| Reichart (2006) | Cr | 2 | 3 | F | 63 68 79 | Reticular Atrophic | Buccal mucosa, Gingiva | 10 12 20 | Ni | 10 | Fixed partial | 100% | 36 | - | |

| Czerninski (2006) | Cr | 2 | 1 | F | 52 | Erosive | 8 | Ni | 3 | Fixed partial | - | 36 | Yes | ||

| Gallego et al. (2008) | Cr | 2 | 1 | F | 81 | Reticular | Buccal mucosa, tongue, palate | - | Yes | 2 | Overdenture | - | 36 | Yes | - |

| Hernandez et al. (2012) | Ps | 1 | 18 | 14F 4M | 53.5 (M) | Erosive | Buccal mucosa Gingiva | - | Yes | 56 | Fixed partial | 100% | 53.5 | Clobetasol propionate 0.05% 3t/d (18 patients) + prednisone 30 mg 1t/d 5-10d (2 patients) | |

| Czerninski et al. (2013) | Rs | 2 | 14 | 11F 3M | 59.5 (M) | Erosive Atrophic Reticular | Buccal mucosa, gingiva | - | Yes | 54 | - | 100% | 12–24 | Dexamethasone 0.4%/triamcinolone 8 mg or clobetasol propionate 0.05% 1-2t/d no more than 2 weeks | |

| Marini et al. (2013) | Cr | 2 | 1 | F | 51 | Reticular | Ni | 2 | Fixed partial | 50% | 108 | Yes | |||

| Moergel et al. (2014) | Cr | 2 | 3 | F | 54 69 80 | - | Yes | 6–51 | Yes | ||||||

| López-jornet et al. (2014) | Rs | 2 | 16 | 10F 6M | 64.5 (M) | Erosive Reticular | - | Yes | 56 | Overdenture Fixed partial | 96.42% | 42 | 0.01% triamcinolone acetonide 3t/d | ||

| Raiser et al. (2016) | Cr | 2 | 2 | F | 55 70 | - | - | - | Ni | 10,6 | Fixed complete, Fixed partial | 100% | 96, 36 | Yes | - |

| Aboushelib et al. (2017) | Ps | 2 | 23 | 12F 11M | 56.7 (M) | - | - | - | Ni | 55 | - | - | Oral corticosteroids + diode laser | ||

| Anitua et al. (2018) | Rs | 1 | 23 | 20F 3M | 58 (M) | Erosive Reticular | Yes | 66 | Fixed partial Fixed complete | 98.5% | 68 | Deflazacort 30 mg 2d preoperatively, 15 mg postoperatively 3d and 7.5 mg 3d | |||

| Fu l et al. (2019) | Cr | 2 | 1 | F | 65 | Erosive | 5 | Yes | 4 | Overdenture | 36 | 0.01% triamcinolone acetonide 3t/d |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torrejon-Moya, A.; Saka-Herrán, C.; Izquierdo-Gómez, K.; Marí-Roig, A.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; López-López, J. Oral Lichen Planus and Dental Implants: Protocol and Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9124127

Torrejon-Moya A, Saka-Herrán C, Izquierdo-Gómez K, Marí-Roig A, Estrugo-Devesa A, López-López J. Oral Lichen Planus and Dental Implants: Protocol and Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(12):4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9124127

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorrejon-Moya, Aina, Constanza Saka-Herrán, Keila Izquierdo-Gómez, Antoni Marí-Roig, Albert Estrugo-Devesa, and José López-López. 2020. "Oral Lichen Planus and Dental Implants: Protocol and Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 12: 4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9124127

APA StyleTorrejon-Moya, A., Saka-Herrán, C., Izquierdo-Gómez, K., Marí-Roig, A., Estrugo-Devesa, A., & López-López, J. (2020). Oral Lichen Planus and Dental Implants: Protocol and Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(12), 4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9124127