4.1. Mental Health in Ukrainian University Students

This study aimed to examine PA’s relationship with the mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results suggest that 37% of the study sample suffered from moderate to severe anxiety and/or depression. Symptoms of depression were significantly more frequently found than symptoms of anxiety. In addition, more people had dual clinically significant mental disorders (anxiety and depression simultaneously) than those who met the singular criteria of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Approximately one-quarter of students may suffer from general anxiety disorders, while nearly one-third may be affected by depression. Furthermore, almost one-fifth of university students manifested symptoms of anxiety and depression concurrently. This means that the vast majority of individuals with anxiety symptoms experienced the comorbidity of depression.

The hypothesis that approximately one-third of the university student population suffered from various forms of depression and anxiety (from moderate to severe symptoms) was confirmed in this research regarding depression, but anxiety levels were lower than expected. The present result is consistent with the study of Feng et al. [

25] but differs from certain previous studies performed in the student population during the COVID-19 pandemic [

18,

20,

21,

28]. The prevalence of depression in the present study sample was 32%. In comparison, between 23% [

18] and 32% [

25] of depression was reported among college and university students in China. General anxiety disorder was found in approximately 24% of Ukrainian university students, as compared to 4% [

24], 28% [

25] and 45% [

18] among Chinese college students, 35% of Polish university students [

20], and 56% in nursing students from Israel [

28]. The mean anxiety score was 6.43 in the present sample of Ukrainian university students, while Jordanian students reported a mean anxiety score of 8.4 [

21]. Anxiety in the present study was lower than in most previous studies reported for both students and general populations.

A review indicated that the prevalence of anxiety and depression ranged between 16–28% of the Chinese population during the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of publishing [

13]. However, differences between particular studies can be seen in mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, moderate to severe anxiety was noted in 29%, whereas moderate to severe depression was reported in 16% of the population living in China during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak [

16,

17]. Among Chinese people younger than 35, 38% reported general anxiety disorder (GAD), and 22% reported depression symptoms [

9,

10]. Ahmed et al. [

6] found 19% of people suffered from anxiety and 27% suffered from symptoms of depression ranging from moderate to severe among 1074 Chinese people living in Hubei province. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and comorbidity of depression and anxiety was 48.3%, 22.6%, and 19.4%, respectively, among people from Wuhan province in China [

52]. Approximately 23% of individuals from Cyprus reported moderate to severe anxiety symptoms, and 9% reported moderate to severe depression symptoms [

22].

The differences between particular studies may be determined, besides cross-cultural differences, by the various methods used to measure anxiety and depression, the distinct quality of the study, and the various cut-off criteria for diagnosing anxiety and depression. A recent meta-analysis indicated that the prevalence of depression assessed using the PHQ-9 scores ≥10 are often overestimated when compared to a diagnosis of major depression on the base of Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (SCID) [

63]. On the other hand, the PHQ is a self-reported screening questionnaire used to detect a risk of depression by an average non-clinician person, so overestimating seems to be a desired feature in this case. Another systematic review and meta-analysis [

64] showed that PHQ-9 has acceptable diagnostic properties for major depressive disorders (with cut-off points between 8–11), and diagnostic accuracy was reasonably consistent despite the clinical heterogeneity of the included studies. Most likely, certain anxiety and depression measures present better sensitivity, specificity, and reliability than others. A previous meta-analysis showed a wide range of differences in the global prevalence of anxiety among medical students, which may also be related to cross-cultural differences [

65]. Moreover, research was conducted at different stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. Many countries in the world introduced several coronavirus-related restrictions in traveling; shopping; access to education, medical and social services; outdoor physical activity; gatherings; and meetings with friends and family. However, these restrictions were changed systematically within each country. As a consequence, a reliable comparison of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic may be very difficult to achieve.

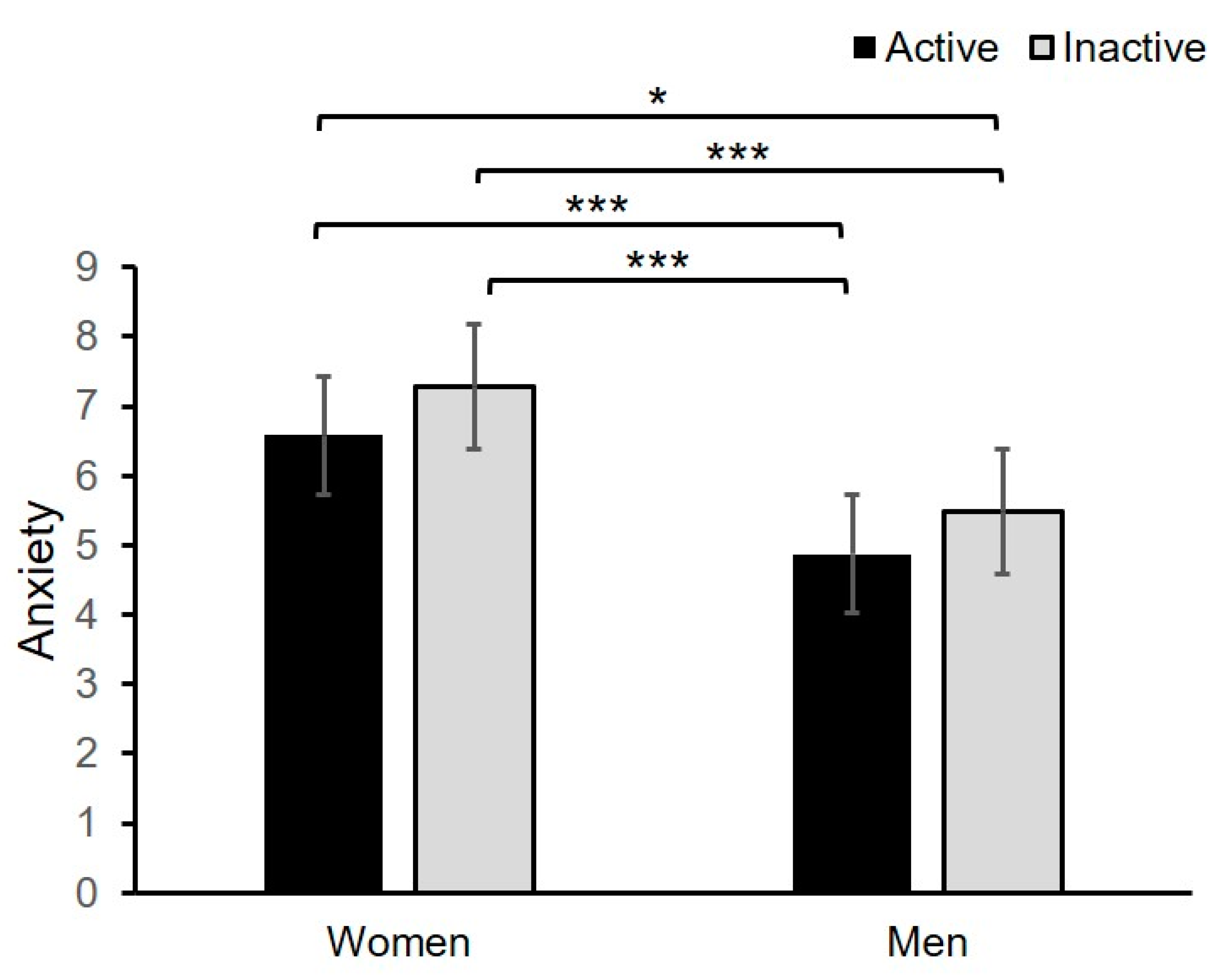

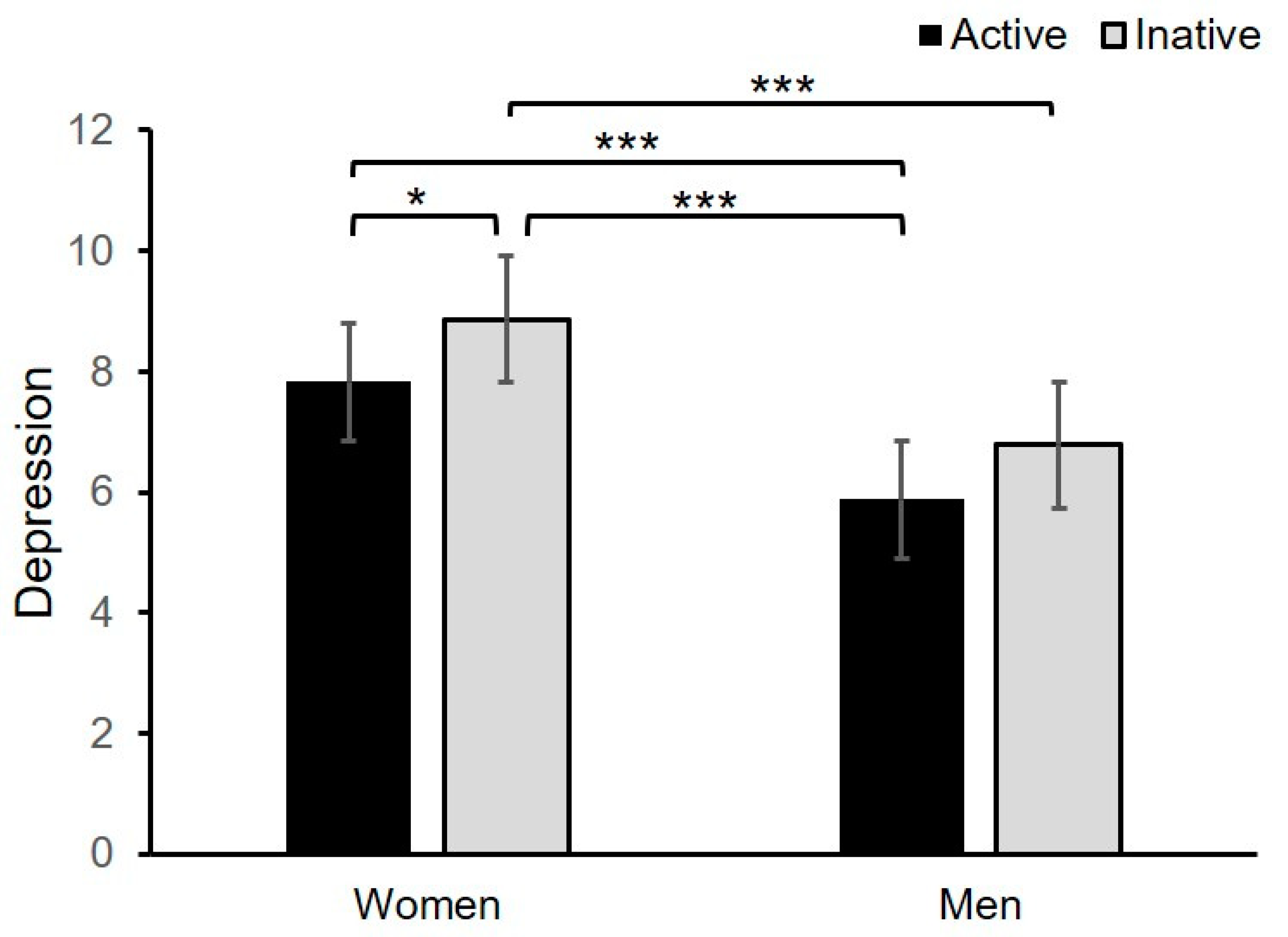

Consistent with most of the previous research, the analysis of variance showed that female Ukrainian university students score higher than men in anxiety and depression [

16,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. However, it is essential to note that these differences are rather weak, since the effect size was very small (η

p2 = 0.03), and sex was not found to be a predictor for both anxiety and depression. Previous research indicated that the fear of the COVID-19 disease was positively related to a younger age, being female, and those more likely to keep smoking and drinking alcohol among medical students in Vietnam [

26]. Among Jordanian university students, higher anxiety was reported in females, individuals with the lowest monthly income, those with less coronavirus knowledge, and those who believed the disease was part of a conspiracy [

21].

The present results do not differ substantially from previous research conducted before the coronavirus pandemic outbreak [

30,

31,

32,

33]. It is confirmed that university and college students experience consistently higher rates of mental health disorders than other populations, which may be slightly elevated by the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown restrictions. The findings from the regression analysis suggest that exposure to COVID-19 and individual differences in the perception of the coronavirus impact (PCI) showed significant but weak associations with anxiety and depression, so other factors may be more important in explaining mental health among Ukrainian university students.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has given rise to many new concerns among the academic population. Besides the usual restrictions, university students have to contend with virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Online learning was not available to many students due to the lack of computers or internet access. During the pandemic, neither the students nor the teachers had been trained in the use of large-scale web-based teaching platforms and technology. Teachers were not familiar with the new online learning methodology. They had to change learning plans to adapt to the unique situation rapidly. Thus, the virtual classes were stressful for both teachers and students [

18,

66,

67,

68,

69].

Furthermore, most of the students lost their part-time jobs which supported them while studying and offered them financial independence [

70]. Adults who lived in dormitories had to return to their family homes and be dependent on their parents. During the first months of the outbreak of the pandemic, a prevalence of uncertainty regarding the near future, examinations, completing classes and finishing studies, the financial situation, and housing and social situation was evident [

69]. Cao et al. [

24] showed that economic factors affected daily life during the COVID-19 pandemic and that delays in academic activities were positively related to anxiety symptoms among Chinese college students. Furthermore, Qiu et al. [

19] suggested that young adults tend to obtain a large amount of information from social media, which may elevate stress. Overall, the SARS-CoV-2 was perceived as a moderately dangerous disease by most students [

21].

4.2. Relationship between PA and Mental Health

The present study suggests that 43% of university students were physically active during the coronavirus lockdown, according to the WHO recommendation (≥150 min/week of PA) [

45]. A previous study found that 56% of Chinese college students were physically active at moderate or vigorous levels during the national quarantine [

18]. The results suggest that the sample of Ukrainian students may be less involved in PA than the group of Chinese undergraduates. However, the previous research [

18] used different measurement methods (i.e., a seven-item International Physical Activity Questionnaire—IPAQ) to assess weekly PA during the last two weeks according to three categories: light, moderate, and vigorous. Thus, the previous and present studies are not fully comparable.

Furthermore, the number of active students decreased significantly in comparison to the situation before the COVID-19 outbreak in Ukraine, which is consistent with some previous studies [

23,

34,

46,

47]. Stanton et al. [

23] showed that negative physical activity changes are associated with increased depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. Research indicates that exercise withdrawal may consistently result in an increase in depressive symptoms and anxiety [

71].

Consistent with other research [

18,

51], this study indicates that there is a significant and inverse relationship between PA and anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. A longitudinal survey showed that PA directly alleviated general negative emotions in college students during the peak time of the COVID-19 outbreak in China [

18]. The volume of moderate-to-vigorous leisure-time PA (MVPA) was also positively associated with mental health and negatively related to the symptoms of anxiety and depression among post-secondary students aged between 16–24 years [

72]. Furthermore, increasing PA during the COVID-19 lockdown was related to lower anxiety and improved well-being among individuals who were inactive before the pandemic [

49].

Ukrainian undergraduates with anxiety and depression symptoms are between 1.6 and 1.9 times less likely to be physically active than their counterparts without mental health problems. This result is consistent with the previous population study of DeMello et al. [

73], which showed that individuals who do not engage in PA are two times more likely to exhibit symptoms of depression and anxiety compared with those who regularly pursue PA. Furthermore, the highest association with PA was found in this study for participants with a dual anxiety and depression diagnosis. Forte et al. [

74] also found that severe depression was most common among adolescents with comorbid anxiety and low PA levels.

The anti-depressive and anxiolytic effects of physical activity on clinical and non-clinical populations were evidenced in a great number of studies e.g., [

70,

71,

75,

76]. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that PA reduces depression by a medium effect and anxiety by a small effect, in non-clinical populations [

77,

78]. Previous meta-analyses found a moderate-to-strong negative relationship between PA and depression and inconsistent association of PA with anxiety (ranged between not statistically significant effect to a moderate beneficial effect of PA on anxiety) in clinical populations. Previous findings suggest that high PA significantly reduced the prevalence of depressive problems, but not anxiety disorders, among Chinese first-year college students [

25]. In contrast, this study found a statistically significant but rather weak association of PA with anxiety and depression. The hierarchical regression model with PA, sex, exposure to COVID-19, and PCI as predictors explained only 14% of anxiety and 15% of depression variability. PA can solely explain 1% of anxiety variability and 3% of depression variability, as shown in the hierarchical regression model in the fourth step of the analysis. Thus, more research is necessary to explain the specific relationship between these variables.

4.3. Limitations of the Study

There are certain limitations to this study. First, the online recruitment method has several limitations. As the research was performed during the lockdown related to the COVID-19 pandemic, all students used remote web-based technologies to learn in virtual educational platforms. An online survey was the only way to perform research on student well-being during the general quarantine. However, the invitation was distributed via Facebook groups, Viber groups, and Telegram channels, so students who do not use these websites could not respond. The online survey results may not be consistent with “paper and pencil” questionnaires. Although the study sample was substantial, there were more female respondents. This proportion is consistent with sex prevalence in typical universities (although technical universities comprise more males). Further research may include a more balanced proportion of the sexes in the study sample. As this research was performed in universities exclusively, the results of this study may not be generalized into more technically focused types of universities. Moreover, this study’s results cannot be generalized into other adult populations, since participants in this study were exclusively university students. Some demographic variables, such as ethnicity, income, employment, marital status, or household members, were not included in the questionnaire. Thus, we do not know if these variables would be more useful as covariates in analyzing the relationship between PA and mental disorder. Further research should include more demographic variables related to the mental health of university students. We used a simple, dichotomous division of people into active and inactive groups according to the WHO recommendation of PA level over the past week. However, other survey questions concerning more details of the level of PA (mild, moderate, vigorous) or time of each of the types could be used in future research. Finally, due to the cross-sectional character of research, the results of the regression analysis should be treated with caution.