Multidisciplinary Pain Management of Chronic Back Pain: Helpful Treatments from the Patients’ Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Multidisciplinary Pain Management Program

2.5.1. Physiotherapy

2.5.2. Aquatic Therapy

2.5.3. Medical Training Therapy

2.5.4. Biofeedback Training

2.5.5. Back Education

2.5.6. Relaxation Therapy

2.5.7. Music Therapy

2.5.8. Psychological Pain Therapy

2.5.9. Medical Supervision

2.6. Measurements/Outcome Parameters

2.6.1. Sociodemographic and Baseline Clinical Data

2.6.2. Primary Outcome Measure: Patients’ Perceived Treatment Helpfulness

2.6.3. Secondary Outcome Measures

Pain Intensity (NRS)

Pain Disability Index (PDI)

Functional Ability (FFbH-R)

German Version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (ADS-L)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Pain-Related Characteristics at Baseline

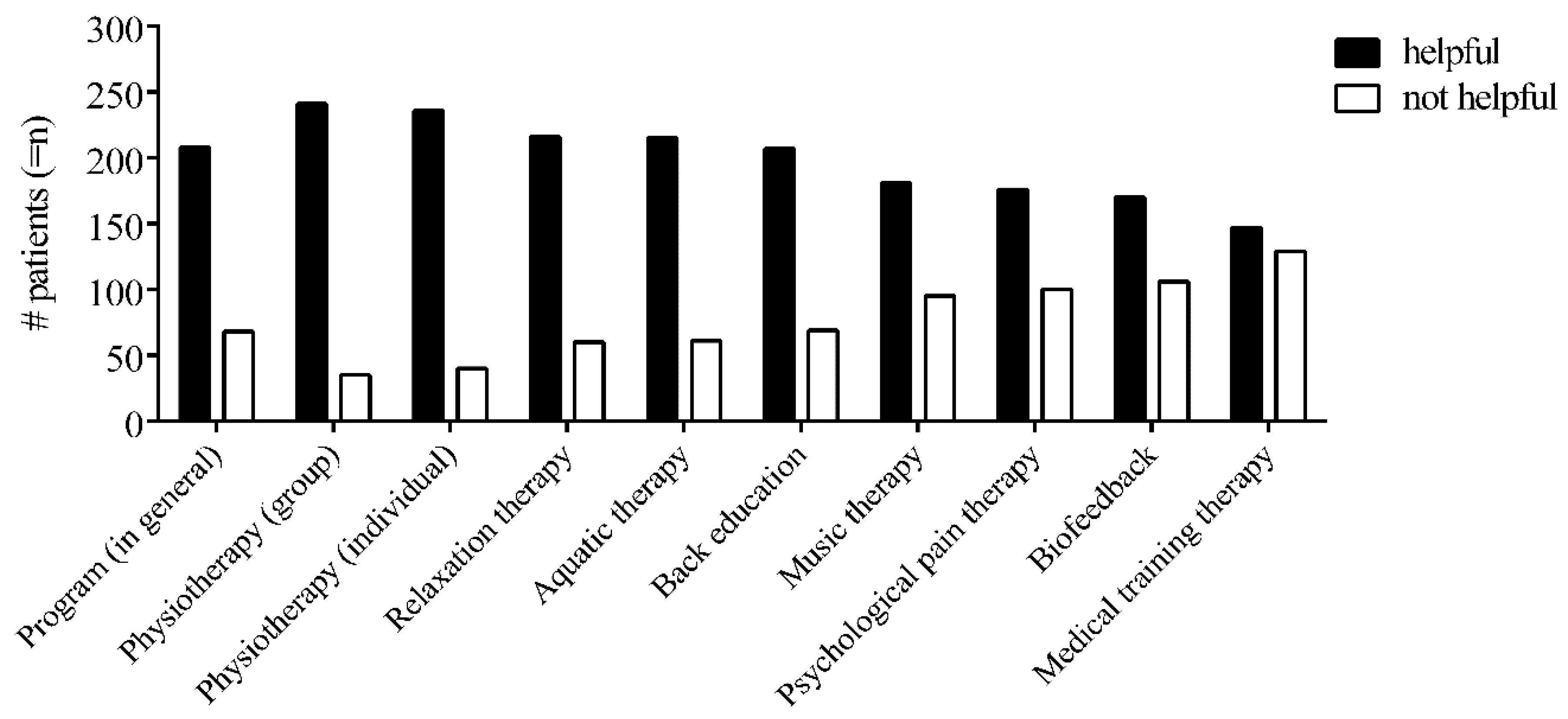

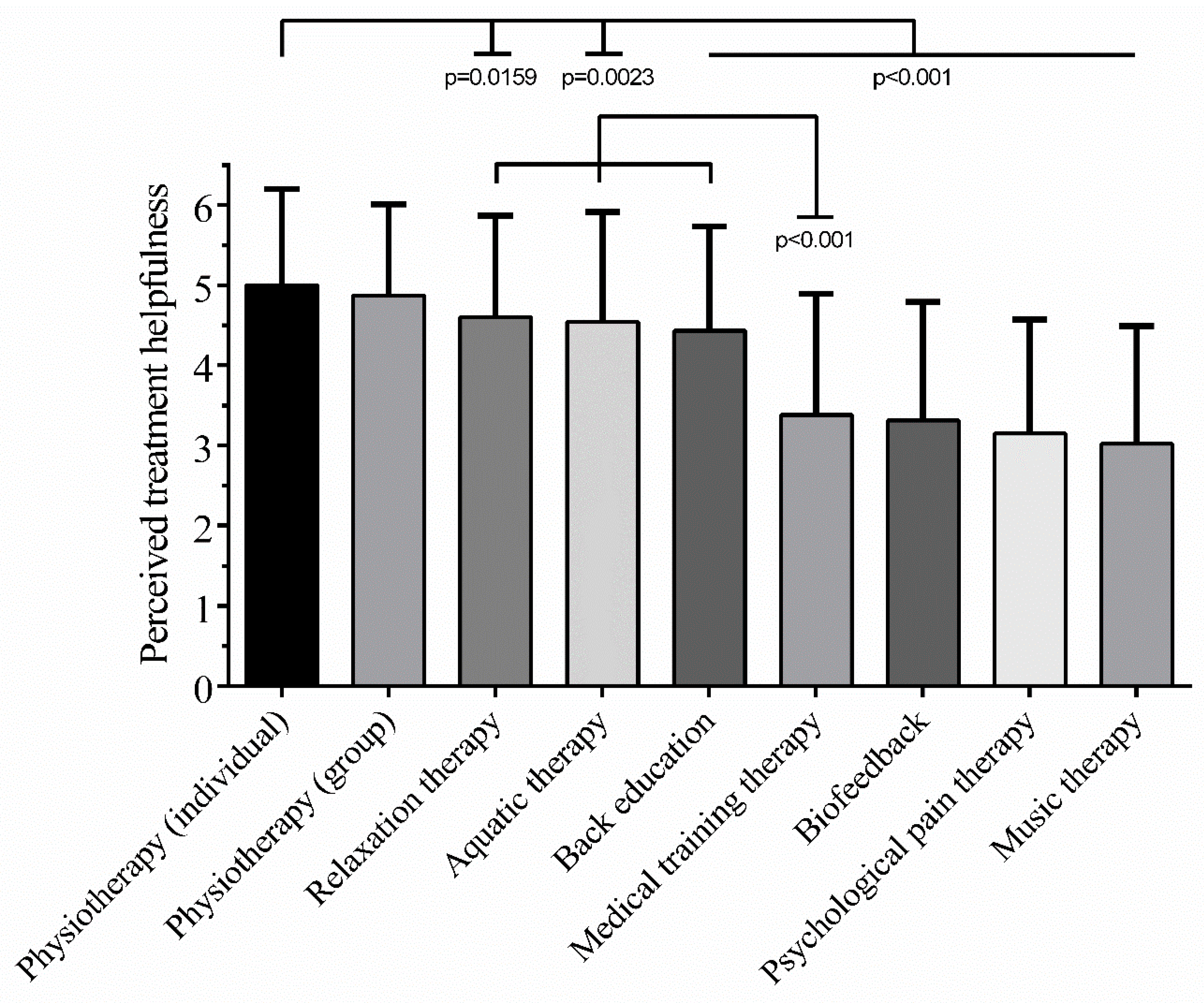

3.2. The Patients’ Perceived Treatment Helpfulness at Discharge

3.3. Influence of Sociodemographic Characteristics on the Patients’ Perceived Helpfulness

3.4. The Multidisciplinary Pain Management Program Reduces Pain-Related Complaints

3.5. The Patients’ Perspective Corresponds to Pain-Related Treatment Outcomes

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nachemson, A. Recent advances in the treatment of low back pain. Int. Orthop. 1985, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O′Connor, S.R.; Tully, M.A.; Ryan, B.; Bleakley, C.M.; Baxter, G.D.; Bradley, J.M.; McDonough, S.M. Walking exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, J.A.; van Tulder, M.W.; Tomlinson, G. Systematic review: Strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 142, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Middelkoop, M.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Kuijpers, T.; Verhagen, A.P.; Ostelo, R.; Koes, B.W.; van Tulder, M.W. A systematic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain. Eur. Spine J. 2011, 20, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tulder, M.W.; Ostelo, R.; Vlaeyen, J.W.; Linton, S.J.; Morley, S.J.; Assendelft, W.J. Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: A systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine 2000, 25, 2688–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatchel, R.J.; McGeary, D.D.; McGeary, C.A.; Lippe, B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: Past, present, and future. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamper, S.J.; Apeldoorn, A.T.; Chiarotto, A.; Smeets, R.J.; Ostelo, R.W.; Guzman, J.; van Tulder, M.W. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015, 350, h444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, J.; Esmail, R.; Karjalainen, K.; Malmivaara, A.; Irvin, E.; Bombardier, C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Systematic review. BMJ 2001, 322, 1511–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, H.; Fydrich, T.; Turk, D.C. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: A meta-analytic review. Pain 1992, 49, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scascighini, L.; Toma, V.; Dober-Spielmann, S.; Sprott, H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: A systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology 2008, 47, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatchel, R.J.; Peng, Y.B.; Peters, M.L.; Fuchs, P.N.; Turk, D.C. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 581–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, R.M.; Hopkins, A.P.; Harvard-Watts, O. Social dimensions of healing: A longitudinal study of outcomes of medical management of headaches. Soc. Sci. Med. 1983, 17, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, R.M.; Bury, M.; Frank, A.O.; Donnelly, T. Problems in the assessment of outcome in a back pain clinic. Int. Disabil. Stud. 1987, 9, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kincey, J.; Bradshaw, P.; Ley, P. Patients‘ satisfaction and reported acceptance of advice in general practice. JR Coll. Gen. Pract. 1975, 25, 558–566. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, S.L.; Jamison, R.N.; Sanders, S.H. Treatment helpfulness questionnaire: A measure of patient satisfaction with treatment modalities provided in chronic pain management programs. Pain 1996, 68, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, B.; Gerbershagen, H.U.; Lindena, G.; Pfingsten, M. Development and evaluation of the multidimensional German pain questionnaire. Schmerz 2002, 16, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbershagen, H. Das Mainzer Stadienkonzept des Schmerzes: Eine Standortbestimmung. In Antidepressiva als Analgetika; Aarachne Verl: Vienna, Austria, 1996; pp. 71–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hampel, P.; Moergel, M.F. Staging of pain in patients with chronic low back pain in inpatient rehabilitation: Validity of the Mainz Pain Staging System of pain chronification. Schmerz 2009, 23, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frettloh, J.; Maier, C.; Gockel, H.; Huppe, M. Validation of the German Mainz Pain Staging System in different pain syndromes. Schmerz 2003, 17, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, F.M.; Abraira, V.; Royuela, A.; Corcoll, J.; Alegre, L.; Tomas, M.; Mir, M.A.; Cano, A.; Muriel, A.; Zamora, J.; et al. Minimum detectable and minimal clinically important changes for pain in patients with nonspecific neck pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2008, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Roer, N.; Ostelo, R.W.; Bekkering, G.E.; van Tulder, M.W.; de Vet, H.C. Minimal clinically important change for pain intensity, functional status, and general health status in patients with nonspecific low back pain. Spine 2006, 31, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, H.H.; Hartvigsen, J.; Manniche, C.; Korsholm, L.; Grunnet-Nilsson, N. Responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference for pain and disability instruments in low back pain patients. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2006, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, J.D.; Piva, S.R.; Fritz, J.M. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain. Spine 2005, 30, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chibnall, J.T.; Tait, R.C. The Pain Disability Index: Factor structure and normative data. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1994, 75, 1082–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, R.C.; Pollard, C.A.; Margolis, R.B.; Duckro, P.N.; Krause, S.J. The Pain Disability Index: Psychometric and validity data. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1987, 68, 438–441. [Google Scholar]

- Tait, R.C.; Chibnall, J.T.; Krause, S. The Pain Disability Index: Psychometric properties. Pain 1990, 40, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronblad, M.; Hupli, M.; Wennerstrand, P.; Jarvinen, E.; Lukinmaa, A.; Kouri, J.P.; Karaharju, E.O. Intercorrelation and test-retest reliability of the Pain Disability Index (PDI) and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODQ) and their correlation with pain intensity in low back pain patients. Clin. J. Pain 1993, 9, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soer, R.; Reneman, M.F.; Vroomen, P.C.; Stegeman, P.; Coppes, M.H. Responsiveness and minimal clinically important change of the Pain Disability Index in patients with chronic back pain. Spine 2012, 37, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmann, T.; Raspe, H. Hannover Functional Questionnaire in ambulatory diagnosis of functional disability caused by backache. Die Rehabil. 1996, 35, I–VIII. [Google Scholar]

- Strand, L.I.; Anderson, B.; Lygren, H.; Skouen, J.S.; Ostelo, R.; Magnussen, L.H. Responsiveness to change of 10 physical tests used for patients with back pain. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautzinger, M.; Bailer, M.; Hofmeister, D.; Keller, F. Allgemeine Depressions Skala. In Manual. 2. Überarbeitete Und Neu Normierte Auflage; Hofgrefe Verlag GmbH & Co KG: Göttingen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the bEhavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard, W.; Lenhard, A. Computation of Effect Sizes; Psychometrica: Dettelbach, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.H. Explaining Psychological Statistics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.L.; Jamison, R.N.; Sanders, S.H.; Lyman, D.R.; Lynch, N.T. Perceived treatment helpfulness and cost in chronic pain rehabilitation. Clin. J. Pain 2000, 16, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillingim, R.B.; King, C.D.; Ribeiro-Dasilva, M.C.; Rahim-Williams, B.; Riley, J.L., 3rd. Sex, gender, and pain: A review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J. Pain 2009, 10, 447–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieh, C.; Altmeppen, J.; Neumeier, S.; Loew, T.; Angerer, M.; Lahmann, C. Gender differences in outcomes of a multimodal pain management program. Pain 2012, 153, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unruh, A.M. Gender variations in clinical pain experience. Pain 1996, 65, 123–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesters, M.; Dahan, A.; Kest, B.; Zacny, J.; Stijnen, T.; Aarts, L.; Sarton, E. Do sex differences exist in opioid analgesia? A systematic review and meta-analysis of human experimental and clinical studies. Pain 2010, 151, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, C.J.; Campbell, C.M.; Edwards, R.R.; Dobs, A.S. Sex-based differences in pain perception and treatment. Pain Med. 2009, 10, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, I.B.; Bergstrom, G.; Ljungquist, T.; Bodin, L.; Nygren, A.L. A randomized controlled component analysis of a behavioral medicine rehabilitation program for chronic spinal pain: Are the effects dependent on gender? Pain 2001, 91, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, F.R.; Bendix, T.; Skov, P.; Jensen, C.V.; Kristensen, J.H.; Krohn, L.; Schioeler, H. Intensive, dynamic back-muscle exercises, conventional physiotherapy, or placebo-control treatment of low-back pain. A randomized, observer-blind trial. Spine 1993, 18, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneen, L.J.; Moore, R.A.; Clarke, C.; Martin, D.; Colvin, L.A.; Smith, B.H. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiltenwolf, M.; Buchner, M.; Heindl, B.; von Reumont, J.; Müller, A.; Eich, W. Comparison of a biopsychosocial therapy (BT) with a conventional biomedical therapy (MT) of subacute low back pain in the first episode of sick leave: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. Spine J. 2006, 15, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (Partial-) Eta-Squared (η2) | Correlation Coefficient (r(s)) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| η2 > 0.01 | r(s) > = 0.10 | small effect |

| η2 > 0.06 | r(s) >= 0.30 | medium effect |

| η2 > 0.14 | r(s) > = 0.50 | large effect |

| Variable | Response | n = | Mean/Percent | SD/Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 276 | 44.5 | 9.073/22–62 | |

| Gender | Female | 157 | 56.9% | |

| Male | 119 | 43.1% | ||

| Marital Status | Unmarried | 55 | 19.9% | |

| Married | 190 | 68.8% | ||

| Widowed | 3 | 1.1% | ||

| Divorced | 28 | 10.1% | ||

| Education | Low | 104 | 37.7% | |

| Intermediate | 87 | 31.5% | ||

| High | 85 | 30.8% | ||

| BMI | Underweight | 5 | 1.8% | |

| Normal | 134 | 48.6% | ||

| Overweight | 103 | 37.3% | ||

| Obese | 34 | 12.3% | ||

| Smoking | Yes | 176 | 63.8% | |

| No | 100 | 36.2% | ||

| Sports Activity | Yes | 183 | 66.3% | |

| No | 93 | 33.7% | ||

| Pain Location | Lower back | 157 | 56.9% | |

| Upper back | 76 | 27.5% | ||

| Both | 43 | 15.6% | ||

| Pain Chronicity | Grade I | 86 | 31.2% | |

| Grade II | 120 | 43.5% | ||

| Grade III | 70 | 25.4% |

| Variable | Response | T0 | T1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = | Percent | Mean | SD | n = | Percent | Mean | SD | ||

| average pain last week | 0 to 10 | 276 | 5.24 | 5.24 | 2.08 | 3.80 | 2.27 | 1.23 | |

| worst pain | 0 to 10 | 276 | 6.97 | 6.97 | 2.13 | 5.80 | 3.80 | 2.02 | |

| least pain | 0 to 10 | 276 | 2.77 | 2.77 | 1.93 | 1.95 | 5.80 | 2.35 | |

| current pain | 0 to 10 | 276 | 4.41 | 4.41 | 2.42 | 3.07 | 1.95 | 1.85 | |

| analgesic intake | no | 88 | 31.9 | 107 | 38.8 | ||||

| yes, occasionally | 87 | 31.5 | 62 | 22.5 | |||||

| yes, regularly | 39 | 14.1 | 32 | 11.6 | |||||

| yes, always | 62 | 22.5 | 75 | 27.2 | |||||

| FFbH-R | overall score | 74.54 | 16.98 | 71.49 | 15.07 | ||||

| normal | 114 | 41.3 | 75 | 27.2 | |||||

| moderate | 53 | 19.2 | 64 | 23.2 | |||||

| abnormal | 44 | 15.9 | 63 | 22.8 | |||||

| clinically relevant | 65 | 23.6 | 74 | 26.8 | |||||

| PDI | overall score | 26.70 | 12.27 | 17.40 | 11.79 | ||||

| low disability | 177 | 64.1 | 230 | 83.3 | |||||

| high disability | 99 | 35.9 | 46 | 16.7 | |||||

| ADS-L | overall score | 19.43 | 9.532 | 9.77 | 8.266 | ||||

| normal | 146 | 52.9 | 232 | 84.1 | |||||

| somatoform disorder - anxious | 50 | 18.1 | 19 | 6.9 | |||||

| depressive symptoms | 27 | 9.8 | 12 | 4.3 | |||||

| depression | 53 | 19.2 | 13 | 4.7 | |||||

| Variable | T0 (n = 276) | T1 (n = 276) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median * | Mean | SD | Median * | p-Value | η2 | |

| Pain average last week | 5.24 | 2.079 | 2 (IQR 1.00; 3.00) | 3.80 | 2.021 | 4 (IQR 2.00; 5.00) | <0.001 | 0.374 |

| Pain worst | 6.97 | 2.127 | 8 (IQR 6.00; 9.00) | 5.80 | 2.350 | 6 (IQR 4.00; 8.00) | <0.001 | 0.244 |

| Pain least | 2.77 | 1.930 | 3 (IQR 1.00; 4.00) | 1.95 | 1.846 | 1 (IQR 1.00; 3.00) | <0.001 | 0.234 |

| Pain current | 4.41 | 2.416 | 4 (IQR 3.00; 6.00) | 3.07 | 2.374 | 3 (IQR 1.00; 5.00) | <0.001 | 0.302 |

| FFbH-R | 74.54 | 16.887 | 75 (IQR 63.00; 88.00) | 71.49 | 15.070 | 71 (IQR 58.00; 83.00) | <0.001 | 0.064 |

| PDI | 26.70 | 12.266 | 25 (IQR 17.25; 35.75) | 17.40 | 11.784 | 15 (IQR 8.25; 26.00) | <0.001 | 0.556 |

| ADS-L | 19.43 | 9.532 | 17 (IQR 12.25; 24.00) | 9.77 | 8.266 | 8 (IQR 4.00; 13.00) | <0.001 | 0.574 |

| Helpfulness of Treatment (Yes/No) | Test | Δ FFbH-R | Δ PDI | Δ ADS-L | Δ Pain Average | Δ Pain Worst | Δ Pain Least | Δ Pain Current |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program (in general) | H (1) = | 13.534 | 7.936 | 3.044 | 17.454 | 19.262 | 9.031 | 8.201 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.081 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.004 | |

| η2 | 0.046 | 0.025 | 0.007 | 0.060 | 0.067 | 0.029 | 0.026 | |

| Physiotherapy (group) | H (1) = | 14.348 | 13.514 | 3.171 | 19.949 | 14.110 | 6.610 | 7.701 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.075 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.010 | 0.006 | |

| η2 | 0.049 | 0.046 | 0.008 | 0.069 | 0.048 | 0.02 | 0.024 | |

| Physiotherapy (individual) | F (1, 274) = | 3.347 | 2.779 | 0.301 | 2.102 | 3.395 | 0.510 | 1.284 |

| p-value | 0.068 | 0.097 | 0.584 | 0.148 | 0.066 | 0.476 | 0.258 | |

| η | 0.012 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.005 | |

| Relaxation therapy | F (1, 274) = | 2.138 | 3.126 | 3.494 | 5.949 | 6.661 | 7.883 | 8.073 |

| p-value | 0.145 | 0.078 | 0.063 | 0.015 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.005 | |

| η2 | 0.008 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.021 | 0.024 | 0.028 | 0.029 | |

| Aquatic therapy | H (1) = | 4.421 | 2.200 | 0.318 | 2.009 | 4.032 | 1.974 | 3.215 |

| p-value | 0.036 | 0.138 | 0.573 | 0.156 | 0.045 | 0.160 | 0.073 | |

| η2 | 0.012 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.008 | |

| Back education | F (1, 274) = | 9.865 | 2.535 | 1.217 | 11.824 | 13.393 | 5.559 | 4.785 |

| p-value | 0.002 | 0.113 | 0.271 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.030 | |

| η2 | 0.035 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.041 | 0.047 | 0.020 | 0.017 | |

| Music therapy | F (1, 274) = | 7.958 | 1.483 | 0.004 | 0.323 | 2.971 | 1.889 | 3.117 |

| p-value | 0.005 | 0.224 | 0.952 | 0.570 | 0.086 | 0.170 | 0.079 | |

| η2 | 0.028 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.011 | |

| Psychological pain therapy | F (1, 274) = | 0.510 | 1.593 | 0.380 | 1.943 | 4.048 | 1.621 | 1.553 |

| p-value | 0.476 | 0.208 | 0.538 | 0.165 | 0.045 | 0.204 | 0.214 | |

| η2 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.006 | |

| Biofeedback | F (1, 274) = | 8.261 | 6.592 | 0.115 | 8.851 | 8.691 | 5.079 | 4.573 |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.735 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.025 | 0.033 | |

| η2 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.018 | 0.016 | |

| Medical training therapy | H (1) = | 9.694 | 6.045 | 0.029 | 5.817 | 10.830 | 1.249 | 1.160 |

| p-value | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.865 | 0.016 | 0.001 | 0.264 | 0.281 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nees, T.A.; Riewe, E.; Waschke, D.; Schiltenwolf, M.; Neubauer, E.; Wang, H. Multidisciplinary Pain Management of Chronic Back Pain: Helpful Treatments from the Patients’ Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010145

Nees TA, Riewe E, Waschke D, Schiltenwolf M, Neubauer E, Wang H. Multidisciplinary Pain Management of Chronic Back Pain: Helpful Treatments from the Patients’ Perspective. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleNees, Timo A., Ernst Riewe, Daniela Waschke, Marcus Schiltenwolf, Eva Neubauer, and Haili Wang. 2020. "Multidisciplinary Pain Management of Chronic Back Pain: Helpful Treatments from the Patients’ Perspective" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010145

APA StyleNees, T. A., Riewe, E., Waschke, D., Schiltenwolf, M., Neubauer, E., & Wang, H. (2020). Multidisciplinary Pain Management of Chronic Back Pain: Helpful Treatments from the Patients’ Perspective. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010145