(Don’t) Look at Me! How the Assumed Consensual or Non-Consensual Distribution Affects Perception and Evaluation of Sexting Images

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Stimuli and Apparatus

2.3. Questionnaires

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Reduction and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Ratings

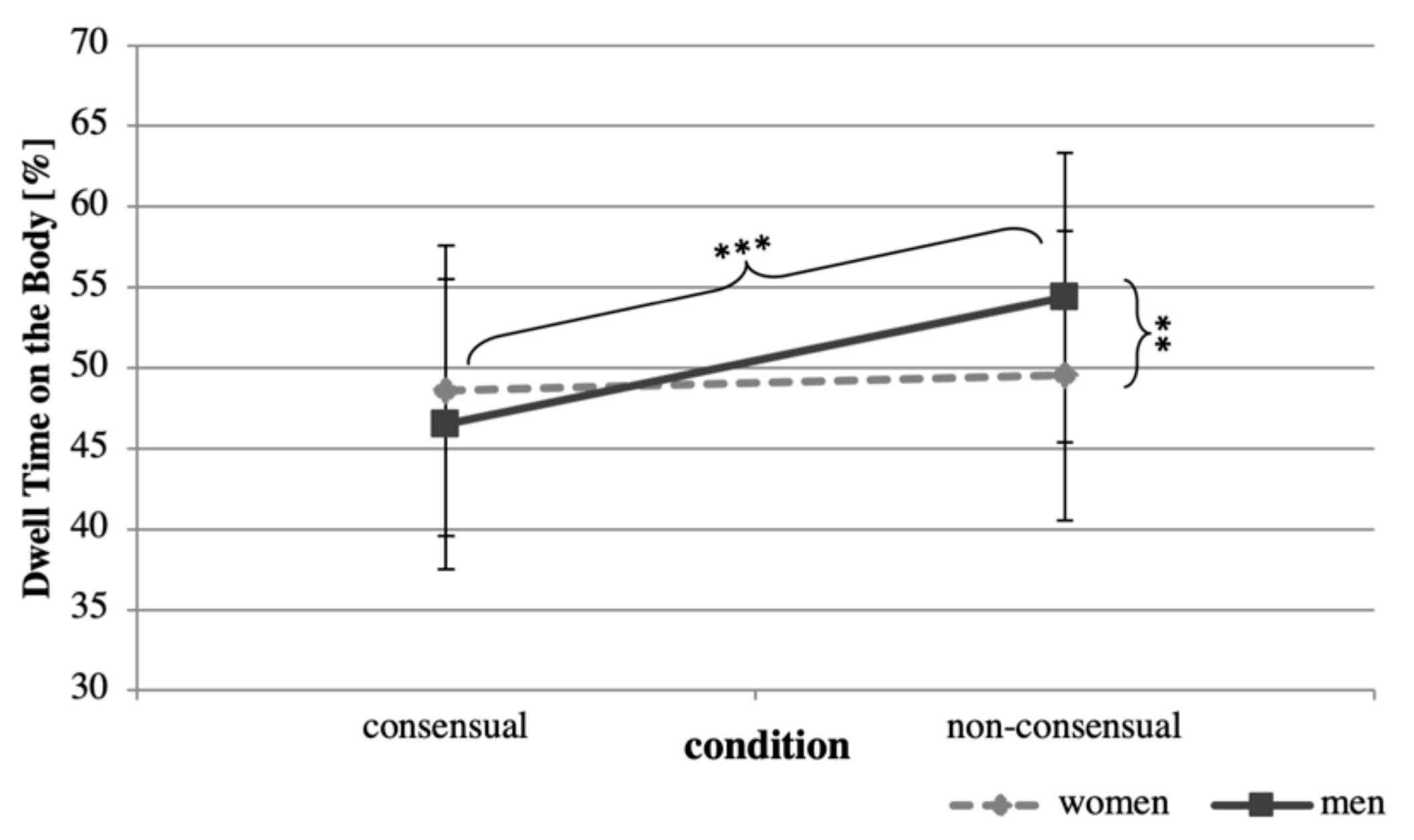

3.3. Eye Tracking Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Image Evaluations

4.2. The Objectifying Gaze

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chalfen, R. “It’s only a picture”: Sexting, “smutty” snapshots and felony charges. Vis. Stud. 2009, 24, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albury, K.; Crawford, K. Sexting, consent and young people’s ethics: Beyond Megan’s Story. Continuum 2012, 26, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klettke, B.; Hallford, D.J.; Mellor, D.J. Sexting prevalence and correlates: A systematic literature review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassberg, D.S.; McKinnon, R.K.; Sustaíta, M.A.; Rullo, J. Sexting by High School Students: An Exploratory and Descriptive Study. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2013, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ouytsel, J.; Walrave, M.; Ponnet, K.; Heirman, W. The Association Between Adolescent Sexting, Psychosocial Difficulties, and Risk Behavior: Integrative Review. J. Sch. Nurs. 2015, 31, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustina, J.R.; Gómez-Durán, E.L. Sexting: Research Criteria of a Globalized Social Phenomenon. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 1325–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, M.A. Unpacking “Sexting”: A Systematic Review of Nonconsensual Sexting in Legal, Educational, and Psychological Literatures. Trauma Violence Abuse 2017, 18, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, J.K. The Indecent Internet: Resisting Unwarranted Internet Exceptionalism Combating Revenge Porn. Berkeley Technol. Law J. 2014, 29, 929–952. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, K.; Sleath, E. A systematic review of the current knowledge regarding revenge pornography and non-consensual sharing of sexually explicit media. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 36, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, S.E.; Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J. Unwanted online sexual solicitation and risky sexual online behavior across the lifespan. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 31, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citron, D.K.; Franks, M.A. Criminalizing revenge porn. Wake Forest Law Rev. 2014, 49, 345–391. [Google Scholar]

- Döring, N. Consensual sexting among adolescents: Risk prevention through abstinence education or safer sexting? Cyberpsychology 2014, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrow, D.G.; Rollo, E.A. Sexting on campus: Minimizing perceived risks and neutralizing behaviors. Deviant Behav. 2014, 35, 903–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, M.; Crofts, T. Responding to revenge porn: Challenges to online legal impunity. In New Views on Pornography: Sexuality, Politics, and the Law; Comella, L., Tarrant, S., Eds.; Praeger Publishers: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 233–256. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud, S.R. The Dark Side of the Online Self: A Pragmatist Critique of the Growing Plague of Revenge Porn. J. Mass Media Ethics 2014, 29, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.R.; Le, V.D.; van den Berg, P.; Ling, Y.; Paul, J.A.; Temple, B.W. Brief report: Teen sexting and psychosocial health. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dir, A.L.; Coskunpinar, A.; Steiner, J.L.; Cyders, M.A. Understanding Differences in Sexting Behaviors Across Gender, Relationship Status, and Sexual Identity, and the Role of Expectancies in Sexting. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, A.R.; Pedersen, C.L. Investigating differences between sexters and non-sexters on attitudes, subjective norms, and risky sexual behaviours. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2015, 24, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentschler, C. #Safetytipsforladies: Feminist Twitter Takedowns of Victim Blaming. Fem. Media Stud. 2015, 15, 353–356. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, N.; Powell, A. Beyond the “sext”: Technology-facilitated sexual violence and harassment against adult women. Aust. N. Z. J. Criminol. 2015, 48, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. “It can happen to you”: Rape prevention in the age of risk management. Hypatia 2004, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rentschler, C.A. Rape culture and the feminist politics of social media. Girlhood Stud. 2014, 7, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C. From “Ladies First” to “Asking for It”: Benevolent Sexism in the Maintenance of Rape Culture. Calif. Law Rev. 2015, 103, 141–204. [Google Scholar]

- Brownmiller, S. Against our will: Women and rape; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, M.R. Cultural myths and supports for rape. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 38, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vance, K.; Sutter, M.; Perrin, P.B.; Heesacker, M. The Media’s Sexual Objectification of Women, Rape Myth Acceptance, and Interpersonal Violence. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2015, 24, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsway, K.A.; Fitzgerald, L.F. Rape myths: In review. Psychol. Women Q. 1994, 18, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Moffitt, L.B.; Carr, E.R. Sexual Objectification of Women: Advances to Theory and Research. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 39, 6–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Roberts, T.-A. Objectification theory. Psychol. Women Q. 1997, 21, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B.; Huang, Y.-P. Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychol. Women Q. 2008, 32, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartky, S.L. Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais, S.J.; Holland, A.M.; Dodd, M.D. My Eyes Are Up Here: The Nature of the Objectifying Gaze Toward Women. Sex Roles 2013, 69, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohner, G. Vergewaltigungsmythen [Rape myths]; Verlag Empirische Pädagogik: Landau, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Eyssel, F.; Bohner, G. Schema Effects of Rape Myth Acceptance on Judgments of Guilt and Blame in Rape Cases: The Role of Perceived Entitlement to Judge. J. Interpers. Violence 2011, 26, 1579–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Süssenbach, P.; Bohner, G.; Eyssel, F. Schematic influences of rape myth acceptance on visual information processing: An eye tracking approach. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süssenbach, P.; Eyssel, F.; Rees, J.; Bohner, G. Looking for Blame Rape Myth Acceptance and Attention to Victim and Perpetrator. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 2323–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollero, C.; Tartaglia, S. The effects of objectification on stereotypical perception and attractiveness of women and men. Psihologija 2016, 49, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, A.B.; Becker, J.V.; Tehee, M.; Mackelprang, E. Sexting Behaviors Among College Students: Cause for Concern? Int. J. Sex. Health 2014, 26, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, S.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. A mediational model linking self-objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychol. Women Q. 1998, 22, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelan, P.; Hargreaves, D. Women Who Objectify Other Women: The Vicious Circle of Objectification? Sex Roles 2005, 52, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerger, H.; Kley, H.; Bohner, G.; Siebler, F. The acceptance of modern myths about sexual aggression scale: Development and validation in German and English. Aggress. Behav. 2007, 33, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Klein, M. Logistic Regression; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, N.R.A. Is Your Teen at Risk? Discourses of adolescent sexting in United States television news. J. Child. Media 2012, 6, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringrose, J.; Harvey, L.; Gill, R.; Livingstone, S. Teen girls, sexual double standards and “sexting”: Gendered value in digital image exchange. Fem. Theory 2013, 14, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N.; Powell, A. Technology-Facilitated Sexual Violence: A Literature Review of Empirical Research. Trauma Violence Abuse 2018, 19, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S. Revenge Porn and Mental Health. A Qualitative Analysis of the Mental Health Effects of Revenge Porn on Female Survivors. Fem. Criminol. 2017, 12, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R. Media, Empowerment and the “Sexualization of Culture” Debates. Sex Roles 2012, 66, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englander, E. Coerced Sexting and Revenge Porn Among Teens. Bullying Teen Aggress. Soc. Media 2015, 1, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlinger, D.A. Eroticizing men: Cultural influences on advertising and male objectification. Sex Roles 2002, 46, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.M. Media and Sexualization: State of Empirical Research, 1995–2015. J. Sex Res. 2016, 53, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.M.; Gervais, S.J.; Canivez, G.L.; Cole, B.P. A psychometric examination of the Interpersonal Sexual Objectification Scale among college men. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeln-Maddox, R.; Miller, S.A.; Doyle, D.M. Tests of Objectification Theory in Gay, Lesbian, and Heterosexual Community Samples: Mixed Evidence for Proposed Pathways. Sex Roles 2011, 65, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, P.; Loughnan, S.; Marchal, C.; Godart, A.; Klein, O. The Exonerating Effect of Sexual Objectification: Sexual Objectification Decreases Rapist Blame in a Stranger Rape Context. Sex Roles 2015, 72, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, S.J.; Bernard, P.; Klein, O.; Allen, J. Toward a Unified Theory of Objectification and Dehumanization. In Objectification and (De)Humanization: 60th Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Gervais, S.J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Heflick, N.A.; Goldenberg, J.L.; Cooper, D.P.; Puvia, E. From women to objects: Appearance focus, target gender, and perceptions of warmth, morality and competence. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvia, E.; Vaes, J. Being a Body: Women’s Appearance Related Self-Views and their Dehumanization of Sexually Objectified Female Targets. Sex Roles 2013, 68, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Hogue, T.; Guo, K. Differential Gaze Behavior towards Sexually Preferred and Non-Preferred Human Figures. J. Sex Res. 2011, 48, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewig, J.; Trippe, R.H.; Hecht, H.; Straube, T.; Miltner, W.H.R. Gender Differences for Specific Body Regions When Looking at Men and Women. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2008, 32, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykins, A.D.; Meana, M.; Strauss, G.P. Sex Differences in Visual Attention to Erotic and Non-Erotic Stimuli. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2008, 37, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nummenmaa, L.; Hietanen, J.K.; Santtila, P.; Hyona, J. Gender and Visibility of Sexual Cues Influence Eye Movements While Viewing Faces and Bodies. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolmont, M.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. Love Is in the Gaze: An Eye tracking Study of Love and Sexual Desire. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1748–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohner, G.; Eyssel, F.; Pina, A.; Siebler, F.; Viki, G.T. Rape myth acceptance: Cognitive, affective and behavioural effects of beliefs that blame the victim and exonerate the perpetrator. In Rape: Challenging contemporary thinking; Horvath, M., Brown, J.M., Eds.; Willan Publishing: Cullompton, UK, 2009; pp. 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Swim, J.K.; Aikin, K.J.; Hall, W.S.; Hunter, B.A. Sexism and racism: Old-fashioned and modern prejudices. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, M. Justice and revenge in online counter-publics: Emerging responses to sexual violence in the age of social media. Crime Media Cult. 2013, 9, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, C.; Jack, R.E.; Scheepers, C.; Fiset, D.; Caldara, R. Culture Shapes How We Look at Faces. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughnan, S.; Fernandez-Campos, S.; Vaes, J.; Anjum, G.; Aziz, M.; Harada, C.; Holland, E.; Singh, I.; Purvia, E.; Tsuchiya, K. Exploring the role of culture in sexual objectification: A seven nations study. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale 2015, 28, 125–152. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, N.T.; Ormerod, A.J. Racialized sexual harassment in the lives of African American women. Women Ther. 2002, 25, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, I.K.; Dinh, K.T.; Bellefontaine, S.A.; Irving, A.L. Sexual Harassment and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms among Asian and White Women. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2012, 21, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Crofts, T. Gender, pressure, coercion and pleasure: Untangling motivations for sexting between young people. Br. J. Criminol. 2015, 55, 454–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodilupo, C.M.; Nadal, K.L.; Corman, L.; Hamit, S.; Lyons, O.B.; Weinberg, A. The manifestation of gender microaggressions. In Microaggressions and Marginality: Manifestation, Dynamics, and Impact; Wing Sue, D., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Somerset, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Papp, L.J.; Erchull, M.J. Objectification and System Justification Impact Rape Avoidance Behaviors. Sex Roles 2017, 76, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, D.L. Female Adolescents, Sexual Empowerment and Desire: A Missing Discourse of Gender Inequity. Sex Roles 2012, 66, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, R.D. Becoming sexual: A critical appraisal of the sexualization of girls; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, E.A.; Zurbriggen, E.L. The price of sexy: Viewers’ perceptions of a sexualized versus nonsexualized Facebook profile photograph. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2016, 5, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manago, A.M.; Graham, M.B.; Greenfield, P.M.; Salimkhan, G. Self-presentation and gender on MySpace. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, G.; Miller, O.S. Effects of Gender and Physical Attractiveness on Visual Attention to Facebook Profiles. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw 2013, 16, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.L.; Hogue, T.; Guo, K. Sexual Cognition Guides Viewing Strategies to Human Figures. J. Sex Res. 2014, 51, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalfen, R. Commentary Sexting as Adolescent Social Communication. J. Child. Media 2010, 4, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasinoff, A.A. Sexting as media production: Rethinking social media and sexuality. New. Media Soc. 2013, 15, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerum, K.; Dworkin, S.L. “Bad Girls Rule”: An Interdisciplinary Feminist Commentary on the Report of the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. J. Sex Res. 2009, 46, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Condition | ||

|---|---|---|

| Consensual a | Non-Consensual b | |

| Female (%) | 52% | 61% |

| Age (M, SD) | 32.20 (11.75) | 31.42 (9.16) |

| Age (Range) | 21–68 | 19–59 |

| AMMSA score (M, SD) | 2.96 (1.33) | 2.44 (0.90) |

| OOS score (of Women; M, SD) | 4.58 (10.86) c | −0.44 (10.16) |

| OOS score (of Men; M, SD) | 0.67 (8.42) | −0.94 (9.67) |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | F | p Value | Coefficient a | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||

| Sexual Attractiveness | Gender | 50.82 | <0.001 | −1.15 | −1.39 | −0.91 |

| Image Gender | 4.34 | 0.038 | 0.38 | −0.50 | 1.26 | |

| Gender × Image Gender | 36.89 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 0.72 | 1.40 | |

| Intimacy | Condition | 0.610 | 0.435 | 0.16 | −0.09 | 0.42 |

| Gender | 0.025 | 0.874 | 0.22 | −0.01 | 0.45 | |

| Group × Gender | 7.029 | 0.008 | −0.46 | −0.80 | −0.12 | |

| Unpleasantness | Condition | 14.02 | <0.001 | −0.37 | −0.56 | −0.18 |

| Gender | 1.47 | 0.225 | −0.34 | −0.60 | −0.07 | |

| Image Gender | 0.52 | 0.473 | 0.18 | −0.93 | 1.28 | |

| Gender × Image Gender | 5.41 | 0.020 | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.82 | |

| AMMSA score | 9.48 | 0.002 | −0.13 | −0.22 | −0.049 | |

| Independent Variable | F | p Value | Coefficient a | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Condition | 12.45 | <0.001 | −7.85 | −11.48 | −4.22 |

| Gender | 1.34 | 0.247 | −4.84 | −7.94 | −1.74 |

| Gender × Condition | 8.36 | 0.004 | 6.92 | 2.22 | 11.61 |

| OOS score | 23.90 | <0.001 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.42 |

| AMMSA score | 31.06 | <0.001 | 2.96 | 1.92 | 4.00 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dekker, A.; Wenzlaff, F.; Daubmann, A.; Pinnschmidt, H.O.; Briken, P. (Don’t) Look at Me! How the Assumed Consensual or Non-Consensual Distribution Affects Perception and Evaluation of Sexting Images. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050706

Dekker A, Wenzlaff F, Daubmann A, Pinnschmidt HO, Briken P. (Don’t) Look at Me! How the Assumed Consensual or Non-Consensual Distribution Affects Perception and Evaluation of Sexting Images. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(5):706. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050706

Chicago/Turabian StyleDekker, Arne, Frederike Wenzlaff, Anne Daubmann, Hans O. Pinnschmidt, and Peer Briken. 2019. "(Don’t) Look at Me! How the Assumed Consensual or Non-Consensual Distribution Affects Perception and Evaluation of Sexting Images" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 5: 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050706

APA StyleDekker, A., Wenzlaff, F., Daubmann, A., Pinnschmidt, H. O., & Briken, P. (2019). (Don’t) Look at Me! How the Assumed Consensual or Non-Consensual Distribution Affects Perception and Evaluation of Sexting Images. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(5), 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050706