Mental Health and Proximal Stressors in Transgender Men and Women

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Mental Health: Anxiety and Depression in Transgender People

1.2. Proximal Stressors in Transgender People

1.3. Associations Between Proximal Stressors and Mental Health for Transgender People

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Predictor Variables

2.3.2. Moderator Variable

2.3.3. Outcome Variables

2.4. Analysis Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Gender Differences in Proximal and Mental Health Variables

3.2. Proximal Aspects and Mental Health for Transgender Men and Women

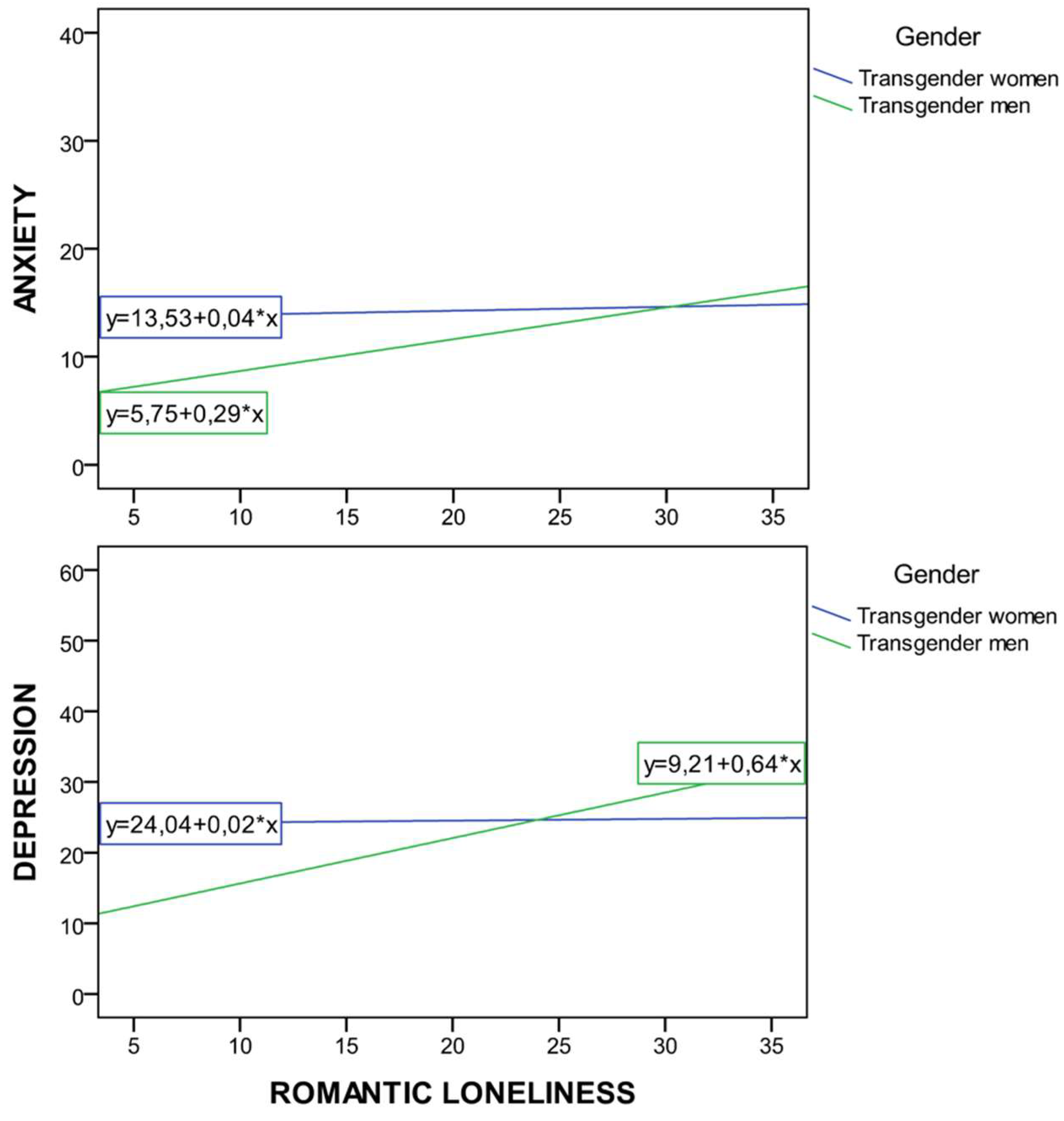

3.3. Proximal Stressors as Predictors of Mental Health (Anxiety and Depression)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernández-Rouco, N.; Carcedo, R.J.; Yeadon-Lee, T. Transgender Identities, Pressures and Social Policy: A Study Carried Out in Spain. J. Homosex. 2018, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress and mental health in lesbian, gay and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, M.L.; Testa, R.J. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2012, 43, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marone, P.; Iacoella, S.; Cecchini, M.; Rabean, A. An Experimental Study of Body Image and Perception in Gender Identity Disorders. Int. J. Transgend. 1998, 2. Available online: http://www.symposion.com/ijt/ijtvo06no01_03.htm (accessed on 15 December 2018).

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.; Oishi, S. Recent findings on subjective Wellbeing. Indian J. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 24, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tilburg, T.; Havens, B.; de Jong Gierveld, J. Loneliness among older adults in the Netherlands, Italy and Canada: A multifaceted comparison. Can. J. Aging. 2004, 23, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snell, W.E. The Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept Questionnaire. In Handbook of Sexuality Related Measures; Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Bauserman, R., Schreer, G., Davis, S.L., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Budge, S.L.; Adelson, J.L.; Howard, K.A. Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support and coping. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrakaki, C.; Vargo, B. The relationship of anxiety and depression: A review of the literature. Br. J. Psychiatry 1986, 149, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, J.M. Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depress. Anxiety 1996, 4, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, E.; Sakamoto, S.; Kijima, N.; Kitamura, T. Different personalities between depression and anxiety. J. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 54, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.I.; Pearson, N.; Coe, N.; Gunnell, D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: Cross-sectional study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 186, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, B.; Glick, I.D.; Baldwin, D.S.; Altamura, A.C. Can long-term outcomes be improved by shortening the duration of untreated illness in psychiatric disorders: A conceptual framework. Psychopathology 2013, 14, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B.; Phelan, J.C. Conceptualizing stigma. Am. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Schauman, O.; Graham, T.; Maggioni, F.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Bezborodovs, N.; Morgan, C.; Rüsch, N.; Brown, J.S.; Thornicroft, G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughto, J.M.W.; Reisner, S.L.; Pachankis, J.E. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms and interventions. Sol. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcelus, J. Non-Suicidal Self Injury in Transsexualism: Associations with Psychological Symptoms, Victimization, Interpersonal Functioning and Perceived Social Support. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 168–179. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski, B.; Andrews, R.; Puckett, J.A. The effects of cumulative victimization on mental health among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adolescents and young adults. Am. J. Public Health Res. 2016, 106, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.L.; Rosario, M.; Slopen, N.; Calzo, J.P.; Austin, S.B. Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: An 11-year longitudinal study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C. The epidemiology of depression among women. In Women and Depression; Keyes, C.L.M., Goodman, S.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements-Nolle, C.; Marx, R.; Guzman, R.; Katz, M. HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, health care use and mental health status of transgender persons: Implications for public health intervention. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 915–921. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto, T.; Bodeker, B.; Iwamoto, M. Social support, exposure to violence and transphobia: Correlates of depression among male-to female transgender women with a history of sex work. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1980–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockting, W.; Coleman, E.; Deutsch, M.B.; Guillamon, A.; Meyer, I.; Meyer, W., III; Reisner, S.; Sevelius, J.; Ettner, R. Adult development and quality of life of transgender and gender nonconforming people. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2016, 23, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koken, J.A.; Bimbi, D.S.; Parsons, J.T. Experiences of familial acceptance–rejection among transwomen of color. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erich, S.; Tittsworth, J.; Kerstein, A.S. An examination and comparison of transsexuals of color and their white counterparts regarding personal well-being and support networks. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2010, 6, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruzinski, T. Psychopatology of body experience: Expanded perspectives. In Body Images: Development, Deviance and Change; Cash, T.F., Pruzinski, T., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York City, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 170–189. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.M.; Reisner, S.L. A systematic review of the effects of hormone therapy on psychological functioning and quality of life in transgender individuals. Transgend. Health 2016, 1, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClelland, S.I. Intimate justice: A critical analysis of sexual satisfaction. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2010, 4, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devor, H. FTM: Female-to-Male Transsexuals in Society; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.R.; Tambor, E.S.; Terdal, S.K.; Downs, D.L. Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health. How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin, M.A.; McCubbin, H.I. Theoretical orientations to family stress and coping. In Treating Stress in Families; Brunner/Mazel: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1989; pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, U.; Robins, R.W.; Meier, L.L. Disentangling the effects of low self-esteem and stressful events on depression: Findings from three longitudinal studies. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Park, L.E. The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 392–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouman, W.P.; Claes, L.; Brewin, N.; Crawford, J.R.; Millet, N.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Arcelus, J. Transgender and anxiety: A comparative study between transgender people and the general population. Int. J. Transgend. 2017, 18, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witcomb, G.L.; Bouman, W.P.; Claes, L.; Brewin, N.; Crawford, J.R.; Arcelus, J. Levels of depression in transgender people and its predictors: Results of a large matched control study with transgender people accessing clinical services. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 235, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruzinsky, T.; Cash, T.F. Integrative themes in body-image development, deviance and change. In Body Images: Development, Deviance and Change; Cash, T.F., Pruzinsky, T., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York City, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 337–349. [Google Scholar]

- Beiter, R.; Nash, R.; McCrady, M.; Rhoades, D.; Linscomb, M.; Clarahan, M.; Sammut, S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety and stress in a sample of college students. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 173, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röder, M.; Barkmann, C.; Richter-Appelt, H.; Schulte-Markwort, M.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Becker, I. Health-related quality of life in transgender adolescents: Associations with body image and emotional and behavioral problems. Int. J. Transgend. 2018, 19, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, K.D.; Kendall, P.C.; Stark, K.; Neumer, S.P. Prevention of anxiety and depression in children: Acceptability and feasibility of the transdiagnostic EMOTION program. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2016, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, A.H.; D’augelli, A.R.; Frank, J.A. Aspects of psychological resilience among transgender youth. J. LGBT Youth 2011, 8, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Burleson, M.H.; Berntson, G.G.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness in everyday life: Cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context and health behaviors. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiTommaso, E.; Brannen, C.; Best, L.A. Measurement and validity characteristics of the short version of the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2004, 64, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Golub, S.A. Family rejection as a predictor of suicide attempts and substance misuse among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. LGBT Health 2016, 3, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, F. Necesidades en la infancia y en la adolescencia. In Respuesta Familiar, Escolar y Social; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, D. Does marital therapy enhance the effectiveness of treatment for sexual dysfunction? J. Sex Marital Ther. 1987, 13, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcedo, R.J.; Perlman, D.; López, F.; Orgaz, M.B.; Toth, K.; Fernández-Rouco, N. Men and women in the same prison: Interpersonal needs and psychological health of prison inmates. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2008, 52, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcedo, R.J.; Perlman, D.; Orgaz, M.B.; López, F.; Fernández-Rouco, N.; Faldowski, R.A. Heterosexual romantic relationships inside of prison: Partner status as predictor of loneliness, sexual satisfaction and quality of life. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2011, 55, 898–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcedo, R.J.; Perlman, D.; López, F.; Orgaz, M.B. Heterosexual romantic relationships, interpersonal needs and quality of life in prison. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcedo, R.J.; Perlman, D.; López, F.; Orgaz, M.B.; Fernández-Rouco, N. The relationship between sexual satisfaction and psychological health of prison inmates. Prison J. 2015, 95, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.A.; Meier, S. Effects of testosterone treatment and chest reconstruction surgery on mental health and sexuality in female-to-male transgender people. Int. J. Sex Health 2014, 26, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmins, L.; Rimes, K.A.; Rahman, Q. Minority stressors and psychological distress in transgender individuals. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2017, 4, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSIC. Código de Buenas Prácticas Científicas del CSIC. Comité de Ética del CSIC. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. 2011. Available online: https://www.cnb.csic.es/documents/CBP_CSIC.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Fitts, W.; Warren, W. Tennessee Self-Concept Scale (2ª Ed.); Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fitts, W.H. The Tennessee Self-Concept Scale, Mind Over Matter; Dept. of Mental Health: Nashivlle, TN, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, T.; Pauly, I. A body image scale for evaluating transsexuals. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1975, 4, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basabe, N.; Valdoseda, M.; Páez, D. Memoria afectiva, salud, formas de afrontamiento y soporte social. In Salud, Expresión y Represión Social de las Emociones; Páez, D., Ed.; Promolibro: Valencia, Spain, 1993; pp. 339–377. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.; Folkman, S. Estrés y Procesos Cognitivos; Martínez Roca: Barcelona, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Lipman, R.S.; Covi, L. SCL-90: An outpatient psychiatric rating scale—Preliminary report. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1973, 9, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erdfelder, E.; Faul, F.; Buchner, A. GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1996, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryanto, A. Heteroskedasticity Test for SPSS (2nd Version). 2018. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/ahmaddaryanto/scripts/Heterogeneity-test (accessed on 28 January 2018).

- Hoffman, B.R. The interaction of drug use, sex work and HIV among transgender women. Subst. Use Misuse 2014, 49, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevelius, J.M.; Reznick, O.G.; Hart, S.L.; Schwarcz, S. Informing interventions: The importance of contextual factors in the prediction of sexual risk behaviors among transgender women. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2009, 21, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirin, S.R.; McCreary, D.R.; Mahalik, J.R. Differential reactions to men and women’s gender role transgressions: Perceptions of social status, sexual orientation and value dissimilarity. J. Mens. Stud. 2004, 12, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maser, J.D.; Cloninger, C.R. Comorbidity of anxiety and mood disorders: Introduction and overview. In Comorbidity of Mood and Anxiety Disorders; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Endler, N.S.; Macrodimitris, S.D.; Kocovski, N.L. Anxiety and Depression: Congruent, Separate or Both? J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2003, 8, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, N.S.; Cox, B.J.; Parker, J.D.; Bagby, R.M. Self-reports of depression and state-trait anxiety: Evidence for differential assessment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.H. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiTommaso, E.; Spinner, B. Social and emotional loneliness: A re-examination of Weiss’ typology of loneliness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1997, 22, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangle, D.W.; Erdley, C.A.; Newman, J.E.; Mason, C.A.; Carpenter, E.M. Popularity, friendship quantity and friendship quality: Interactive influences on children’s loneliness and depression. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2003, 32, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.J.; Harwood, R.H.; Blizard, R.A.; Thomas, A.; Mann, A.H. Social support deficits, loneliness and life events as risk factors for depression in old age. The Gospel Oak Project VI. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segrin, C.; Powell, H.L.; Givertz, M.; Brackin, A. Symptoms of depression, relational quality and loneliness in dating relationships. Pers. Relatsh. 2003, 10, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dear, G.E.; Thomson, D.M.; Hall, G.J.; Hall, K. Self-inflicted injury and coping behaviours in prison. In Suicide Prevention: The Global Context; Kosky, R.J., Eshkevarky, S., Hassan, R., Goldney, R., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 198–199. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski, B.S.; Garofalo, R.; Emerson, E.M. Mental health disorders, psychological distress and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youths. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 2426–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N = 120 | Answer Range | Mean | SD | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tr. Men | Tr. Women | Tr. Men | Tr. Women | ||||

| Anxiety | 1–5 | 1.13 | 1.43 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 1.92 | <0.05 |

| Depression | 1–5 | 1.65 | 1.89 | 0.94 | 0.98 | ||

| Body Image | 1–5 | 2.81 | 3.09 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 2.35 | <0.05 |

| Self-esteem | 1–5 | 3.42 | 3.44 | 0.54 | 0.53 | ||

| Active coping | 1–4 | 2.74 | 2.79 | 0.48 | 0.48 | ||

| Soc. support coping | 1–4 | 2.59 | 2.52 | 0.58 | 0.72 | ||

| Avoidant coping | 1–4 | 2.17 | 2.25 | 0.46 | 0.50 | ||

| Social loneliness | 1–7 | 3.30 | 3.54 | 1.39 | 1.45 | ||

| Family loneliness | 1–7 | 3.78 | 3.54 | 1.67 | 1.77 | ||

| Romantic loneliness | 1–7 | 3.82 | 4.39 | 1.55 | 1.39 | 2.13 | <0.05 |

| Sexual satisfaction | 1–5 | 2.53 | 2.91 | 0.99 | 1.10 | 2.01 | <0.05 |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxiety | 0.75 * | −0.29 ** | −0.22 * | −0.09 | −0.06 | 0.29 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.19 * | −0.19 * | |

| 2. Depression | −0.53 ** | −0.45 ** | −0.26 ** | −0.25 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.59 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.41 ** | ||

| 3. Body image | 0.41 ** | 0.18 * | 0.20 * | −0.46 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.17 | 0.51 ** | |||

| 4. Self esteem | 0.51 ** | 0.25 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.57 ** | −0.54 ** | −0.23 ** | 0.33 ** | ||||

| 5. Active cop. | 0.32 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.10 | 0.24 ** | |||||

| 6. Soc. supp. cop. | −0.24 ** | −0.18 * | −0.27 ** | 0.02 | −0.03 | ||||||

| 7. Avoidant cop. | 0.33 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.17 | −0.33 ** | |||||||

| 8. Fam. lonel. | 0.69 ** | 0.12 | −0.19 * | ||||||||

| 9. Soc. lonel. | 0.31 ** | −0.26 ** | |||||||||

| 10. Rom. lonel. | −0.38 ** | ||||||||||

| 11. Sex. satisfact. |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxiety | 1 | 0.73 ** | −0.22 | −0.26 * | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.23 | 0.47 ** | 0.52 | 0.29 * | −0.22 |

| 2. Depression | 0.77 ** | 1 | −0.51 ** | −0.56 ** | −0.20 | −0.28 * | 0.52 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.40 ** | −0.47 ** |

| 3. Body image | −0.44 ** | −0.63 ** | 1 | 0.34 ** | 0.04 | 0.15 | −0.33 ** | −0.31 * | −0.21 | −0.24 | 0.57 ** |

| 4. Self esteem | −0.19 | −0.36 ** | 0.48 ** | 1 | 0.49 ** | 0.22 | −0.36 ** | −0.62 ** | −0.65 ** | −0.32 * | 0.36 ** |

| 5. Active cop. | −0.17 | −0.33** | 0.29 * | 0.53 ** | 1 | 0.35 ** | −0.25 | −0.37 ** | −0.44 ** | −0.01 | 0.12 |

| 6. Soc. supp. cop. | −0.03 | −0.21 | 0.26 * | 0.28 * | 0.29 * | 1 | −0.31 * | −0.18 | −0.19 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| 7. Avoidant cop. | 0.34 ** | 0.63 ** | −0.60 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.42 ** | −0.18 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.40 ** | 0.36 ** | −0.44 ** |

| 8. Fam. lonel. | 0.38 ** | 0.43 ** | −0.51 ** | −0.52 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.20 | 0.43 ** | 1 | 0.71 ** | 0.16 | −0.17 |

| 9. Soc. lonel. | 0.44 ** | 0.49 ** | −0.51 ** | −0.44 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.32 * | 0.38 ** | 0.69 ** | 1 | 0.41 ** | −0.35 ** |

| 10. Rom. lonel. | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.20 | −0.15 | −0.23 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 1 | −0.47 ** |

| 11. Sex. satisfact. | −0.24 | −0.43 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.32 * | 0.36 ** | −0.06 | −0.26 * | −0.19 | −0.23 | −0.39 ** | 1 |

| Anxiety | Depression | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | 95% CI (LL, UL) | Predictor Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | 95% CI (LL, UL) | ||||

| (B) | SE B | (B) | SE B | (B) | SE B | (B) | SE B | ||||

| Step 1: Proximal Stressors: | Step 1: Proximal Stressors: | ||||||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.07 | (−0.05, 0.33) | Self-esteem | 0.05 | −0.18 | −0.05 | −0.03 | (−0.25, 0.14) |

| Body image | −0.14 | −0.11 | −0.22 | −0.19 | (−0.19, 0.04) | Body image | −0.25 *** | −0.35 | −0.31 *** | −0.23 | (−0.24, −0.05) |

| Avoidant coping | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.10 | (−0.36, 0.62) | Active coping | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | (−0.24, 1.23) |

| Family loneliness | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.13 | (−0.12, 0.32) | Soc. support coping | −0.03 | −0.10 | −0.02 | −0.05 | (−0.97, 0.31) |

| Social loneliness | 0.56 *** | 0.50 | 0.51 *** | 0.45 | (0.33, 0.68) | Avoidant coping | 0.32 *** | 0.40 | 0.33 *** | 0.30 | (0.63, 1.77) |

| Rom. loneliness | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 | (−0.29, 0.10) | Family loneliness | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.07 | (−0.14, 0.40) |

| Sex. satisfaction | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.12 | −0.13 | (−0.47, 0.12) | Social loneliness | 0.37 *** | 0.60 | 0.26 *** | 0.27 | (0.21, 0.71) |

| Rom. loneliness | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.06 | −0.12 | (−0.34, 0.13) | ||||||

| Sex. satisfaction | −0.11 | −0.28 | −0.13 | −0.15 | (−0.67, −0.03) | ||||||

| Moderator | Moderator | ||||||||||

| Gender | −0.14 | −0.13 | 0.49 | 0.51 | (−5.80, −0.31) | Gender | −0.14 | −0.07 | 0.39 | 0.33 | (−6.09, −0.65) |

| Step 2: Interaction model: | Step 2: Interaction model: | ||||||||||

| Self−esteem × Gend. | 0.48 | 0.50 | (−0.26, 0.25) | Active cop. × Gend. | 0.10 | 0.14 | (−1.9, 1.35) | ||||

| Body image × Gend. | 0.19 | 0.21 | (−0.11, 0.20) | Soc. sup. cop. × Gend. | −0.20 | −0.24 | (−1.80, 0.68) | ||||

| Avoidant cop. × Gend. | 0.34 | 0.35 | (−0.84, 1.11) | Rom. lonel × Gend. | −0.58 *** | −0.58 | (−0.95, −0.20) | ||||

| Rom. lonel. × Gend. | −0.46 *** | −0.22 | (−0.26, −0.04) | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.24 | 0.29 | R2 | 0.54 | 0.58 | ||||||

| ∆R2 | 0.24 *** | 0.05 ** | ∆R2 | 0.05 *** | 0.04 *** | ||||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Rouco, N.; Carcedo, R.J.; López, F.; Orgaz, M.B. Mental Health and Proximal Stressors in Transgender Men and Women. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030413

Fernández-Rouco N, Carcedo RJ, López F, Orgaz MB. Mental Health and Proximal Stressors in Transgender Men and Women. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(3):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030413

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Rouco, Noelia, Rodrigo J. Carcedo, Félix López, and M. Begoña Orgaz. 2019. "Mental Health and Proximal Stressors in Transgender Men and Women" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 3: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030413

APA StyleFernández-Rouco, N., Carcedo, R. J., López, F., & Orgaz, M. B. (2019). Mental Health and Proximal Stressors in Transgender Men and Women. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(3), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030413