Contingency Contracts for Weight Gain of Patients with Anorexia Nervosa in Inpatient Therapy: Practice Styles of Specialized Centers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Study Centers

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measures

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

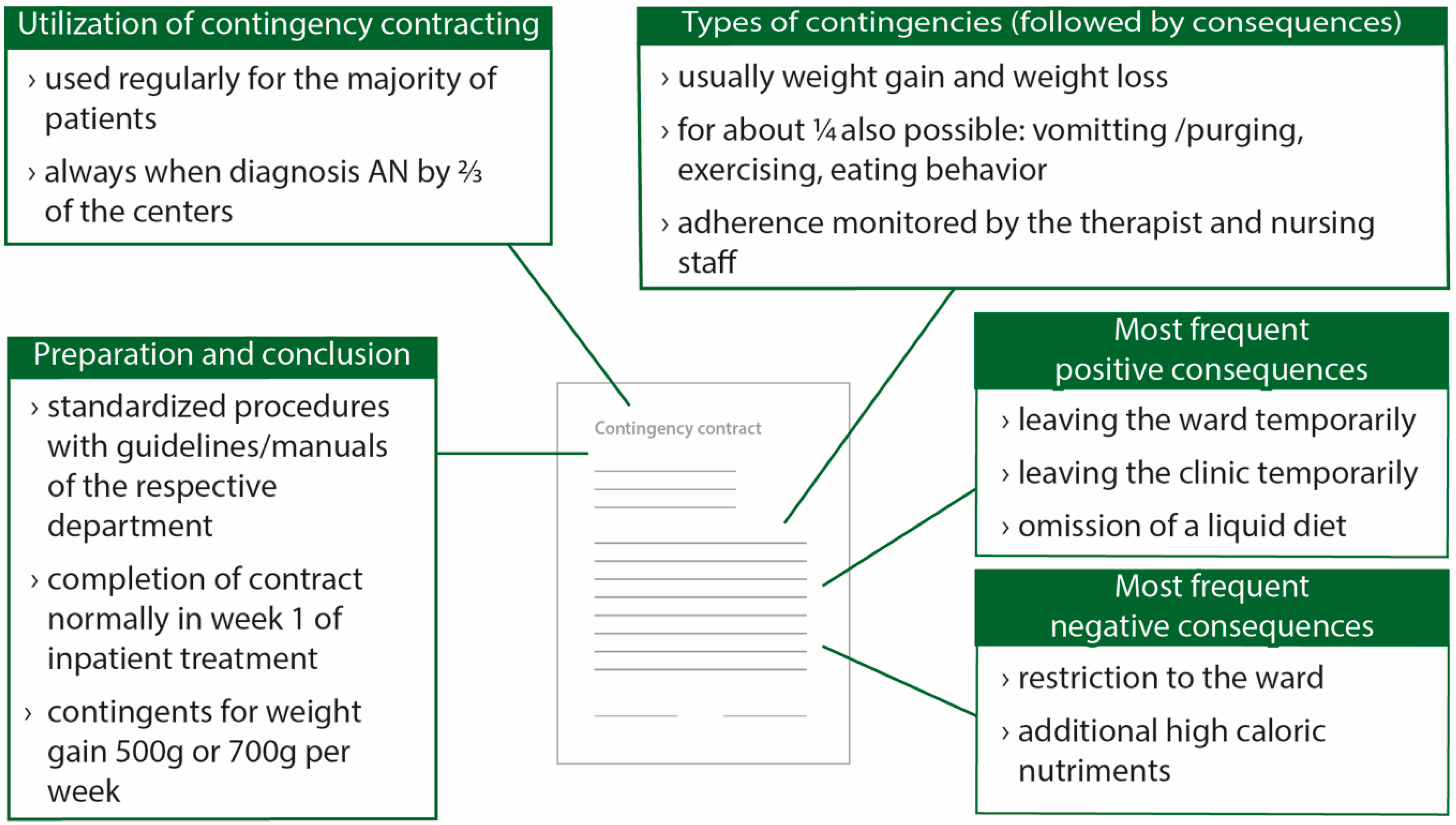

3.1. Utilization

3.2. Preparation and Conclusion

3.3. Weight Contingencies and Weight Goals

3.4. Revisiting, Changing and Terminating Contingency Contracts

3.5. Consequences

3.6. Overall Effectiveness and Factors of Success from the Experts’ Points of View

3.7. Emotions Experienced by the Experts during the Contingency Contract Negotiation and Emotional Burden

3.8. Group Differences

4. Discussion

4.1. Similarities of Contingency Contracts in Specialized Eating Disorder Centers

4.2. Differences of Contingency Contracts in Specialized Eating Disorder Centers

4.3. Collaborative Approaches within the Contingency Contract Process

4.4. Implications for Clinical Practice

4.5. Experiences of Experts with the Contingency Contract Process

4.6. Limitations and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi, F.; Höfler, M.; Strehle, J.; Mack, S.; Gerschler, A.; Scholl, L.; Busch, M.A.; Hapke, U.; Maske, U.; Seiffert, I. Twelve-months prevalence of mental disorders in the German health interview and examination survey for adults–Mental health module (DEGS1-MH): A methodological addendum and correction. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 24, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipfel, S.; Giel, K.E.; Bulik, C.M.; Hay, P.; Schmidt, U. Anorexia nervosa: Aetiology, assessment, and treatment. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcelus, J.; Mitchell, A.J.; Wales, J.; Nielsen, S. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, C.A.; Golden, N.H. An introduction to eating disorders: Clinical presentation, epidemiology, and prognosis. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2010, 25, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipfel, S.; Löwe, B.; Reas, D.L.; Deter, H.-C.; Herzog, W. Long-term prognosis in anorexia nervosa: Lessons from a 21-year follow-up study. Lancet 2000, 355, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockell, S.J.; Geller, J.; Linden, W. Decisional balance in anorexia nervosa: Capitalizing on ambivalence. Eur. Eating Disord. Rev. 2003, 11, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate-Daga, G.; Amianto, F.; Delsedime, N.; De-Bacco, C.; Fassino, S. Resistance to treatment and change in anorexia nervosa: A clinical overview. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herpertz, S.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Fichter, M.; Tuschen-Caffier, B.; Zeeck, A. S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Behandlung der Essstörungen; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sly, R.; Morgan, J.F.; Mountford, V.A.; Lacey, J.H. Predicting premature termination of hospitalised treatment for anorexia nervosa: The roles of therapeutic alliance, motivation, and behaviour change. Eating Behav. 2013, 14, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeeck, A.; Hartmann, A. Relating therapeutic process to outcome: Are there predictors for the short-term course in anorexic patients? Eur. Eating Disord. Rev. 2005, 13, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegl, S.; Quadflieg, N.; Löwe, B.; Cuntz, U.; Voderholzer, U. Specialized inpatient treatment of adult anorexia nervosa: Effectiveness and clinical significance of changes. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keel, P.K.; Brown, T.A. Update on course and outcome in eating disorders. Int. J. Eating Disord. 2010, 43, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, A.; Zeeck, A.; Barrett, M.S. Interpersonal problems in eating disorders. Int. J. Eating Disord. 2010, 43, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legenbauer, T.; Vocks, S. Manual der kognitiven Verhaltenstherapie bei Anorexie und Bulimie; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schauenburg, H.; Friederich, H.-C.; Wild, B.; Zipfel, S.; Herzog, W. Fokale psychodynamische psychotherapie der anorexia nervosa. Psychotherapeut 2009, 54, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, W.; Friederich, H.-C.; Wild, B.; Löwe, B.; Zipfel, S. Magersucht. Therapeutische Umschau 2006, 63, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziser, K.; Resmark, G.; Giel, K.E.; Becker, S.; Stuber, F.; Zipfel, S.; Junne, F. The effectiveness of contingency management in the treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa: A systematic review. Eur. Eating Disord. Rev. 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgart, E.-J.; Meermann, R. Essstörungen; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Guideline Alliance UK. Eating Disorders: Recognition and Treatment; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hebebrand, J.; Bulik, C.M. Critical appraisal of the provisional DSM-5 criteria for anorexia nervosa and an alternative proposal. Int. J. Eating Disord. 2011, 44, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, T.; Zeeck, A.; Hartmann, A.; Nickel, T. Lower targets for weekly weight gain lead to better results in inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa: A pilot study. Eur. Eating Disord. Rev. 2004, 12, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanto, M.V.; Jacobson, M.S.; Heller, L.; Golden, N.H.; Hertz, S. Rate of weight gain of inpatients with anorexia nervosa under two behavioral contracts. Pediatrics 1994, 93, 989–991. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garber, A.K.; Sawyer, S.M.; Golden, N.H.; Guarda, A.S.; Katzman, D.K.; Kohn, M.R.; Le Grange, D.; Madden, S.; Whitelaw, M.; Redgrave, G.W. A systematic review of approaches to refeeding in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eating Disord. 2016, 49, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.; Reid, M. Understanding the experience of ambivalence in anorexia nervosa: The maintainer’s perspective. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, J.; Brown, K.E.; Zaitsoff, S.L.; Goodrich, S.; Hastings, F. Collaborative versus directive interventions in the treatment of eating disorders: Implications for care providers. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2003, 34, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.K.; Reilly, E.E.; Berner, L.; Wierenga, C.E.; Jones, M.D.; Brown, T.A.; Kaye, W.H.; Cusack, A. Treating eating disorders at higher levels of care: Overview and challenges. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, J.; Dunn, E.C. Integrating motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of eating disorders: Tailoring interventions to patient readiness for change. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2011, 18, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunyan, M.; Crowley, J.; Smedley, N.; Mutti, M.F.; Cashen, A.; Thompson, T.; Foster, J. Feasibility of training nurses in motivational interviewing to improve patient experience in mental health inpatient rehabilitation: A pilot study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nursing 2017, 24, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mander, J.; Teufel, M.; Keifenheim, K.; Zipfel, S.; Giel, K.E. Stages of change, treatment outcome and therapeutic alliance in adult inpatients with chronic anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federici, A.; Kaplan, A.S. The patient’s account of relapse and recovery in anorexia nervosa: A qualitative study. Eur. Eating Disord. Rev. 2008, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M (SD) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender: female | 71.1 | |

| Clinical experience in psychotherapy/psychosomatic medicine/psychiatry in years | 7.75 (7.20) | |

| Occupational group | ||

| Medical doctor | 61.8 | |

| Clinical psychologist | 36.8 | |

| Both | 1.3 | |

| Estimated number of treated patients with anorexia nervosa | ||

| <20 | 34.2 | |

| 20–40 | 23.7 | |

| 41–60 | 14.5 | |

| 61–80 | 6.6 | |

| 81–100 | 9.2 | |

| >100 | 11.8 | |

| Main therapeutic orientation | ||

| Cognitive-behavior psychotherapy | 29.7 | |

| Psychodynamic psychotherapy | 70.3 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ziser, K.; Giel, K.E.; Resmark, G.; Nikendei, C.; Friederich, H.-C.; Herpertz, S.; Rose, M.; De Zwaan, M.; Von Wietersheim, J.; Zeeck, A.; et al. Contingency Contracts for Weight Gain of Patients with Anorexia Nervosa in Inpatient Therapy: Practice Styles of Specialized Centers. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7080215

Ziser K, Giel KE, Resmark G, Nikendei C, Friederich H-C, Herpertz S, Rose M, De Zwaan M, Von Wietersheim J, Zeeck A, et al. Contingency Contracts for Weight Gain of Patients with Anorexia Nervosa in Inpatient Therapy: Practice Styles of Specialized Centers. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2018; 7(8):215. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7080215

Chicago/Turabian StyleZiser, Katrin, Katrin E. Giel, Gaby Resmark, Christoph Nikendei, Hans-Christoph Friederich, Stephan Herpertz, Matthias Rose, Martina De Zwaan, Jörn Von Wietersheim, Almut Zeeck, and et al. 2018. "Contingency Contracts for Weight Gain of Patients with Anorexia Nervosa in Inpatient Therapy: Practice Styles of Specialized Centers" Journal of Clinical Medicine 7, no. 8: 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7080215

APA StyleZiser, K., Giel, K. E., Resmark, G., Nikendei, C., Friederich, H.-C., Herpertz, S., Rose, M., De Zwaan, M., Von Wietersheim, J., Zeeck, A., Dinkel, A., Burgmer, M., Löwe, B., Sprute, C., Zipfel, S., & Junne, F. (2018). Contingency Contracts for Weight Gain of Patients with Anorexia Nervosa in Inpatient Therapy: Practice Styles of Specialized Centers. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(8), 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7080215