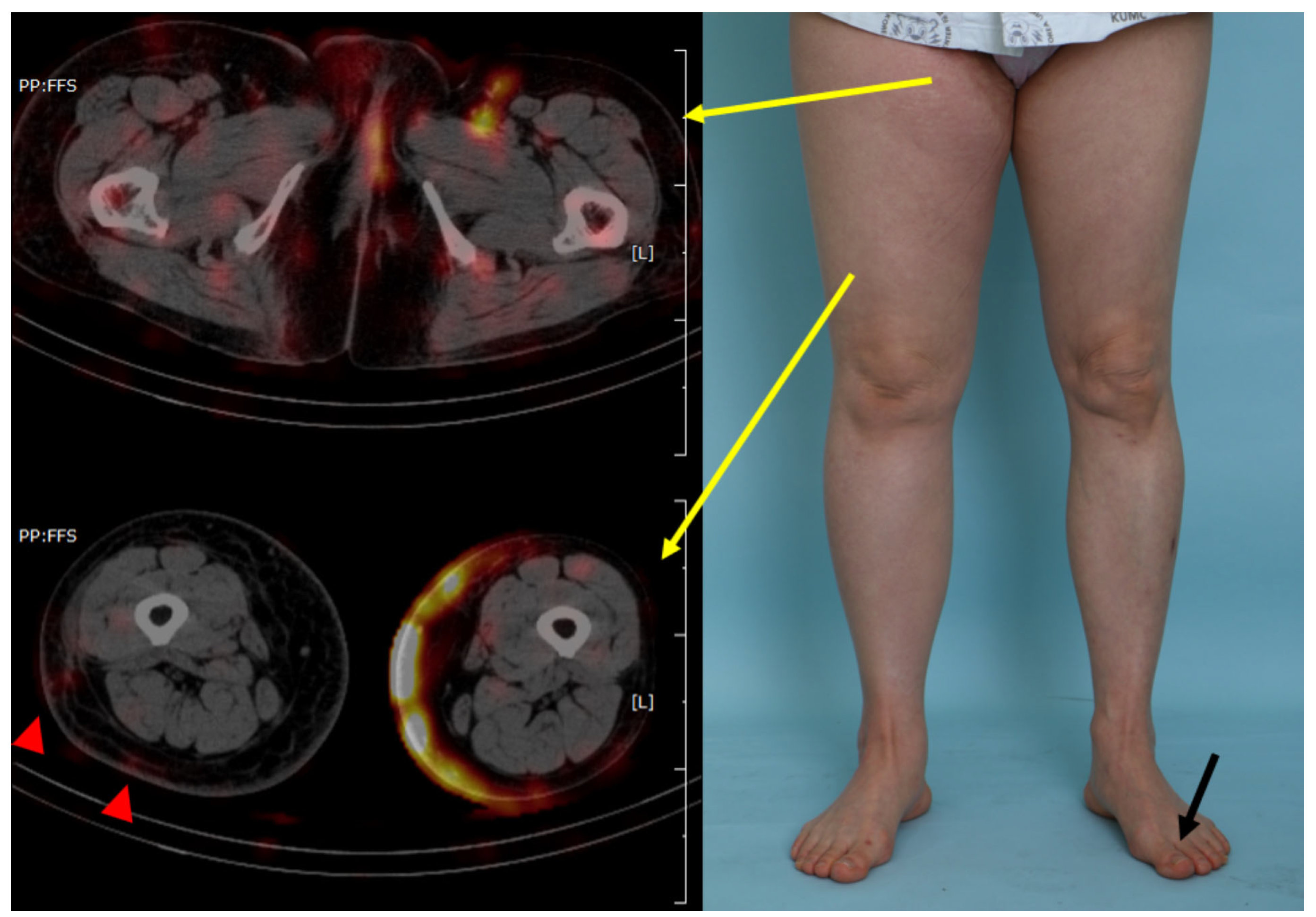

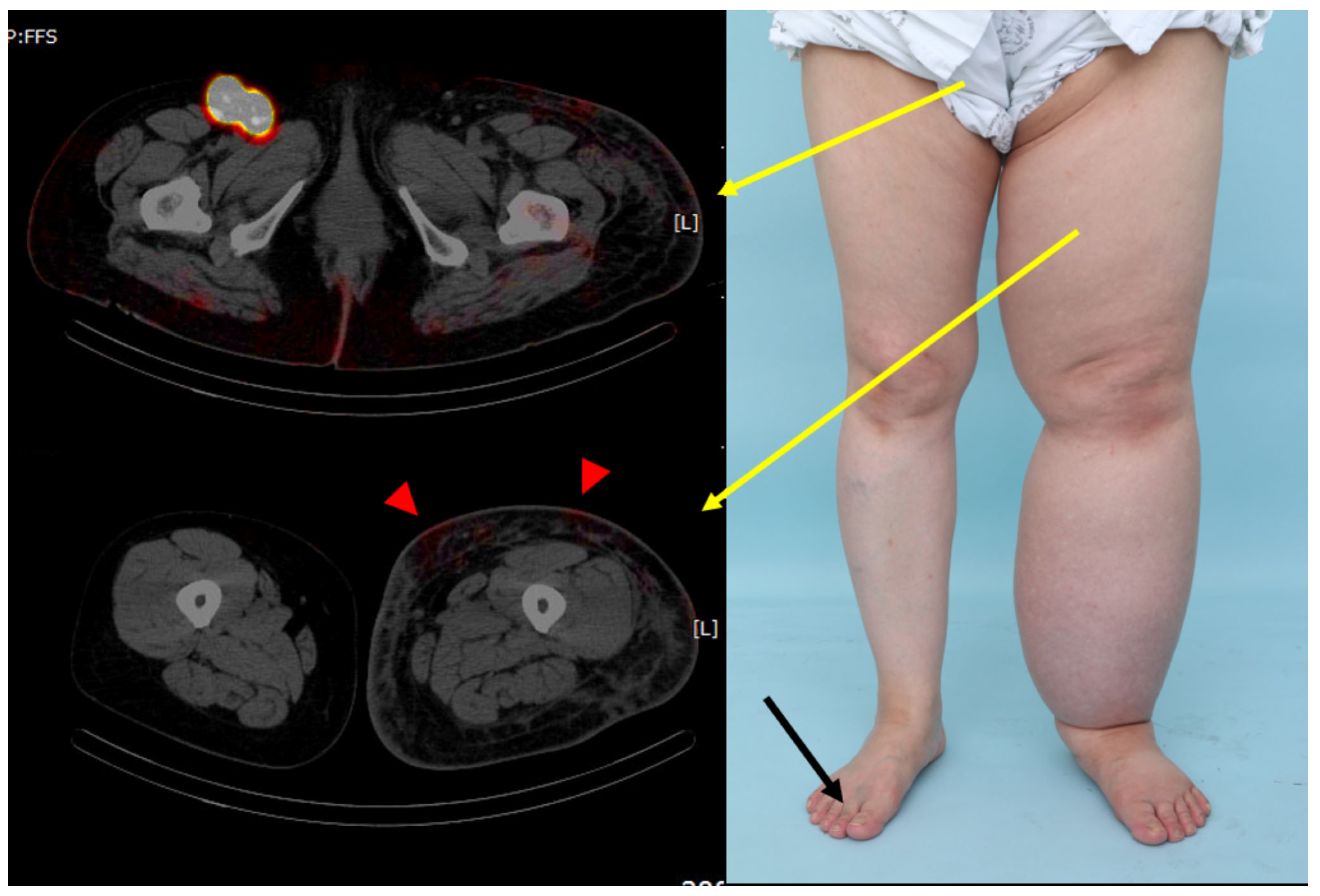

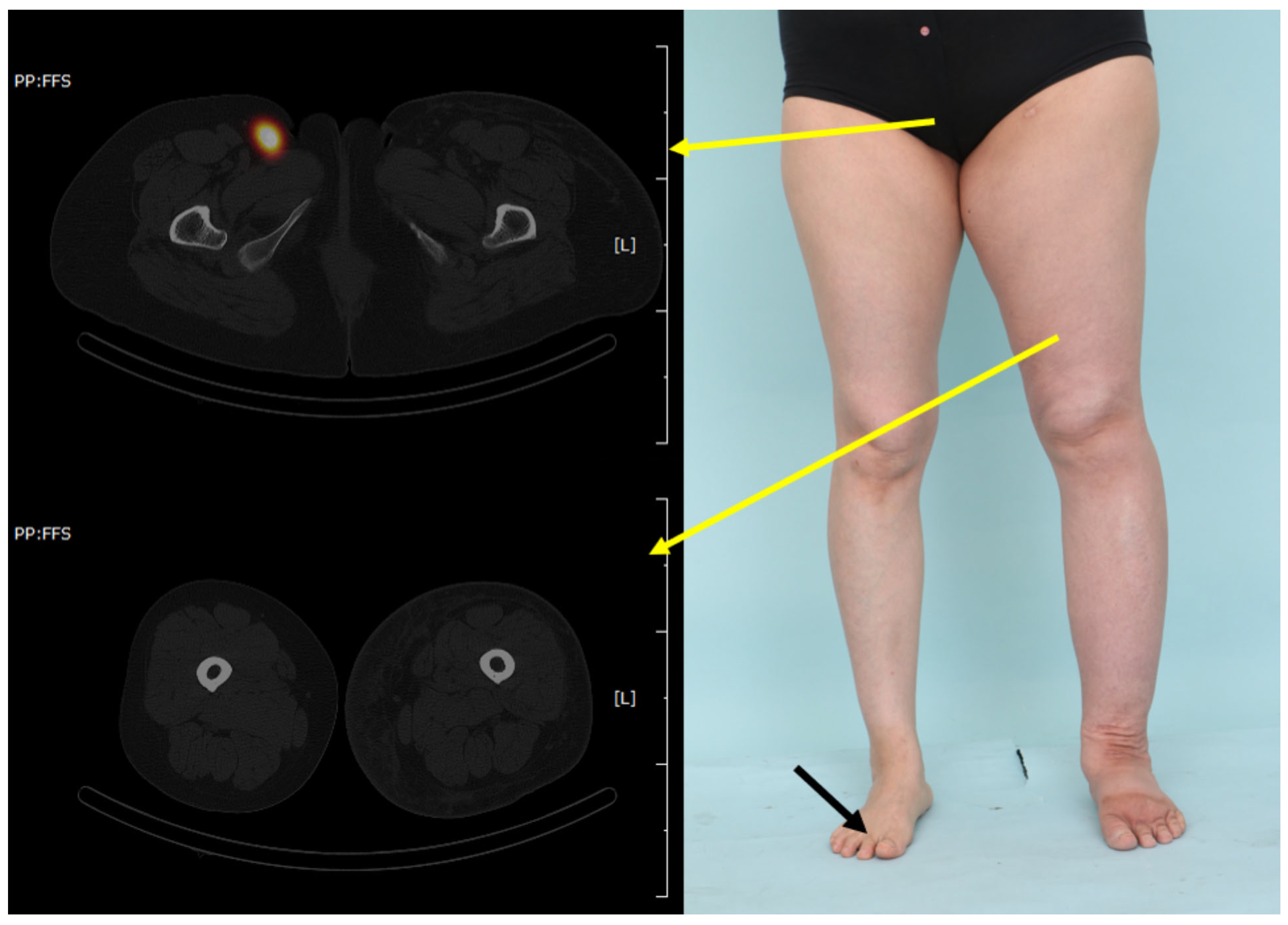

Reverse Lymphatic Flow in Lower Extremity Lymphedema Visualized on Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography—A “Downflow Effect”

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Radiological Visualization of the Lymphatic Flow (SPECT/CT)

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Measurement of Limb Volume

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Greene, A.K.; Goss, J.A. Diagnosis and staging of lymphedema. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2018, 32, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Kataru, R.P.; Mehrara, B.J. Histopathologic features of lymphedema: A molecular review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessources, K.; Aviki, E.; Leitao, M.M., Jr. Lower extremity lymphedema in patients with gynecologic malignancies. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, J.N.; Askew, R.L.; Mungovan, K.S.; Xing, Y.; Ross, M.I.; Armer, J.M. Lymphedema beyond breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cancer-related secondary lymphedema. Cancer 2010, 116, 5138–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schook, C.C.; Mulliken, J.B.; Fishman, S.J.; Grant, F.D.; Zurakowski, D.; Greene, A.K. Primary lymphedema: Clinical features and management in 138 pediatric patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 127, 2419–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shallwani, S.M.; Hodgson, P.; Towers, A. Comparisons between cancer-related and noncancer-related lymphedema: An overview of new patients referred to a specialized hospital-based center in canada. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2017, 15, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polomska, A.K.; Proulx, S.T. Imaging technology of the lymphatic system. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 170, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baulieu, F.; Bourgeois, P.; Maruani, A.; Belgrado, J.P.; Tauveron, V.; Lorette, G.; Vaillant, L. Contributions of SPECT/CT imaging to the lymphoscintigraphic investigations of the lower limb lymphedema. Lymphology 2013, 46, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weiss, J.; Daniel, T. Validation of the lymphedema life impact scale (Llis): A condition-specific measurement tool for persons with lymphedema. Lymphology 2015, 48, 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Brorson, H.; Hoijer, P. Standardised measurements used to order compression garments can be used to calculate arm volumes to evaluate lymphoedema treatment. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2012, 46, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhar, S.H.; Lim, H.Y.; Tan, B.-K.; Angeli, V. The unresolved pathophysiology of lymphedema. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, K.; Hamad, M.M.; Sadek, S.; Awdeh, M.; Eklof, B.; Abdel-Dayem, H.M. Dynamic lymph flow imaging in lymphedema. Normal and abnormal patterns. Clin. Nucl. Med. 1986, 11, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaleska, M.T.; Olszewski, W.L. Imaging lymphatics in human normal and lymphedema limbs-usefulness of various modalities for evaluation of lymph and edema fluid flow pathways and dynamics. J. Biophotonics 2018, 11, e201700132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.-J.; Woo, K.-J.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kang, S.Y.; Moon, B.S.; Kim, B.S. The added value of SPECT/CT lymphoscintigraphy in the initial assessment of secondary extremity lymphedema patients. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suehiro, K.; Morikage, N.; Murakami, M.; Yamashita, O.; Samura, M.; Hamano, K. Re-evaluation of qualitative lymphangioscintigraphic findings in secondary lower extremity lymphedema. Surg. Today 2014, 44, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissleder, H.; Weissleder, R. Lymphedema: Evaluation of qualitative and quantitative lymphoscintigraphy in 238 patients. Radiology 1988, 167, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, H.; Suami, H.; Thompson, B.M.; Ngo, Q.; Heydon-White, A.; Blackwell, R.; Koelmeyer, L.A. Retrograde lymph flow in the lymphatic vessels in limb lymphedema. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2022, 10, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iimura, T.; Fukushima, Y.; Kumita, S.; Ogawa, R.; Hyakusoku, H. Estimating lymphodynamic conditions and lymphovenous anastomosis efficacy using (99m)Tc-phytate lymphoscintigraphy with SPECT-CT in patients with lower-limb lymphedema. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2015, 3, e404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshiri, M.; Katz, D.S.; Boris, M.; Yung, E. Using lymphoscintigraphy to evaluate suspected lymphedema of the extremities. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2002, 178, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.K.; Lopez, M.; Iles, K.; Kugar, M. Surgical Approach to Lymphedema Reduction. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 22, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadal Castells, M.J.; Ramirez Mirabal, E.; Cuartero Archs, J.; Perrot Gonzalez, J.C.; Beranuy Rodriguez, M.; Pintor Ojeda, A.; Bascuñana Ambros, H. Effectiveness of lymphedema prevention programs with compression garment after lymphatic node dissection in breast cancer: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2021, 2, 727256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Sex (Male:Female) | 1:9 |

| Mean age ± SD, years | 53.1 ± 10.9 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| None | 10 (100%) |

| Current | 0 |

| Medical history other than lymphedema-related disease, n(%) | |

| None | 6 (60.0%) |

| Hypertension | 2 (20.0%) |

| Diabetes | 0 |

| Hepatitis | 2 (20.0%) |

| Others | 1 (10.0%) |

| Mean BMI ± SD, kg/m2 | 26.2 ± 2.9 |

| ISL Stage, n (%) | |

| Stage 2 | 8 (80.0%) |

| Stage 3 | 2 (20.0%) |

| Affected side (Right:Left) | 6:4 |

| Etiology, n (%) | |

| Primary lymphedema | 2 (20.0%) |

| Cervical cancer | 7 (70.0%) |

| Others | 1 (10.0%) |

| Lymphatic structure invasion, n(%) | |

| Pelvic lymph node dissection | 10 (100%) |

| Chemotherapy | 10 (100%) |

| Radiotherapy | 10 (100%) |

| Mean duration of the disease ± SD, years | 9.4 ± 8.1 |

| Prior therapies for lymphedema, n(%) | |

| Compression therapy | 10 (100%) |

| Surgical intervention | 0 |

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Circumference ratio (affected to unaffected limbs), mean ± SD | |

| Upper thigh (point 1) | 1.13 ± 0.09 |

| Midthigh (point 2) | 1.18 ± 0.11 |

| Superior border of patella (point 3) | 1.15 ± 0.10 |

| Inferior border of patella (point 4) | 1.19 ± 0.12 |

| Midcalf (point 5) | 1.16 ± 0.10 |

| Ankle (point 6) | 1.19 ± 0.16 |

| Mean volume ratio (affected to unaffected limbs) | 1.36 ± 0.23 |

| LLIS score, mean ± SD | |

| Physical concerns | 23.9 ± 7.4 |

| Psychosocial concerns | 12.5 ± 3.3 |

| Functional concerns | 17.9 ± 5.4 |

| Overall score | 54.3 ± 15.9 |

| Result | N |

|---|---|

| Negative finding (Neither pelvic retention nor retrograde lymphatic flow) | 3 (30.0%) |

| Pelvic retention only | 1 (10.0%) |

| Lower limb retrograde lymphatic flow only | 0 |

| Pelvic retention with lower limb retrograde lymphatic flow | 6 (60.0%) |

| Extent of lower limb retrograde lymphatic flow | |

| Thigh | 6 out of 6 (100%) |

| Characteristics | R | NR | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circumference ratio (affected to unaffected limbs), mean ± SD | |||

| Upper thigh (point 1) | 1.14 ± 0.10 | 1.11 ± 0.07 | 0.796 |

| Midthigh (point 2) | 1.17 ± 0.12 | 1.21 ± 0.10 | 0.587 |

| Superior border of patella (point 3) | 1.13 ± 0.08 | 1.20 ± 0.14 | 0.269 |

| Inferior border of patella (point 4) | 1.17 ± 0.14 | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 0.089 |

| Midcalf (point 5) | 1.17 ± 0.12 | 1.16 ± 0.04 | 0.181 |

| Ankle (point 6) | 1.17 ± 0.17 | 1.24 ± 0.17 | 0.941 |

| Mean volume ratio (affected to unaffected limbs) | 1.33 ± 0.26 | 1.42 ± 0.16 | 0.374 |

| LLIS score, mean ± SD | |||

| Physical concerns | 24.0 ± 7.4 | 23.6 ± 8.9 | 0.728 |

| Psychosocial concerns | 12.7 ± 3.1 | 12.0 ± 4.3 | 0.475 |

| Functional concerns | 18.1 ± 5.8 | 17.3 ± 5.1 | 0.631 |

| Overall score | 54.8 ± 16.3 | 53 ± 18.1 | 0.857 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, J.W.; Song, H.-S.; Kim, C.; Lee, T.-Y.; You, H.-J.; Kim, D.-W. Reverse Lymphatic Flow in Lower Extremity Lymphedema Visualized on Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography—A “Downflow Effect”. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030942

Lee JW, Song H-S, Kim C, Lee T-Y, You H-J, Kim D-W. Reverse Lymphatic Flow in Lower Extremity Lymphedema Visualized on Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography—A “Downflow Effect”. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):942. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030942

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jun Won, Han-Sang Song, Chulhan Kim, Tae-Yul Lee, Hi-Jin You, and Deok-Woo Kim. 2026. "Reverse Lymphatic Flow in Lower Extremity Lymphedema Visualized on Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography—A “Downflow Effect”" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030942

APA StyleLee, J. W., Song, H.-S., Kim, C., Lee, T.-Y., You, H.-J., & Kim, D.-W. (2026). Reverse Lymphatic Flow in Lower Extremity Lymphedema Visualized on Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography—A “Downflow Effect”. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030942