When Every Minute Counts: Predicting Pre-Hospital Deliveries and Neonatal Risk in Emergency Medical Services Using Data-Driven Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

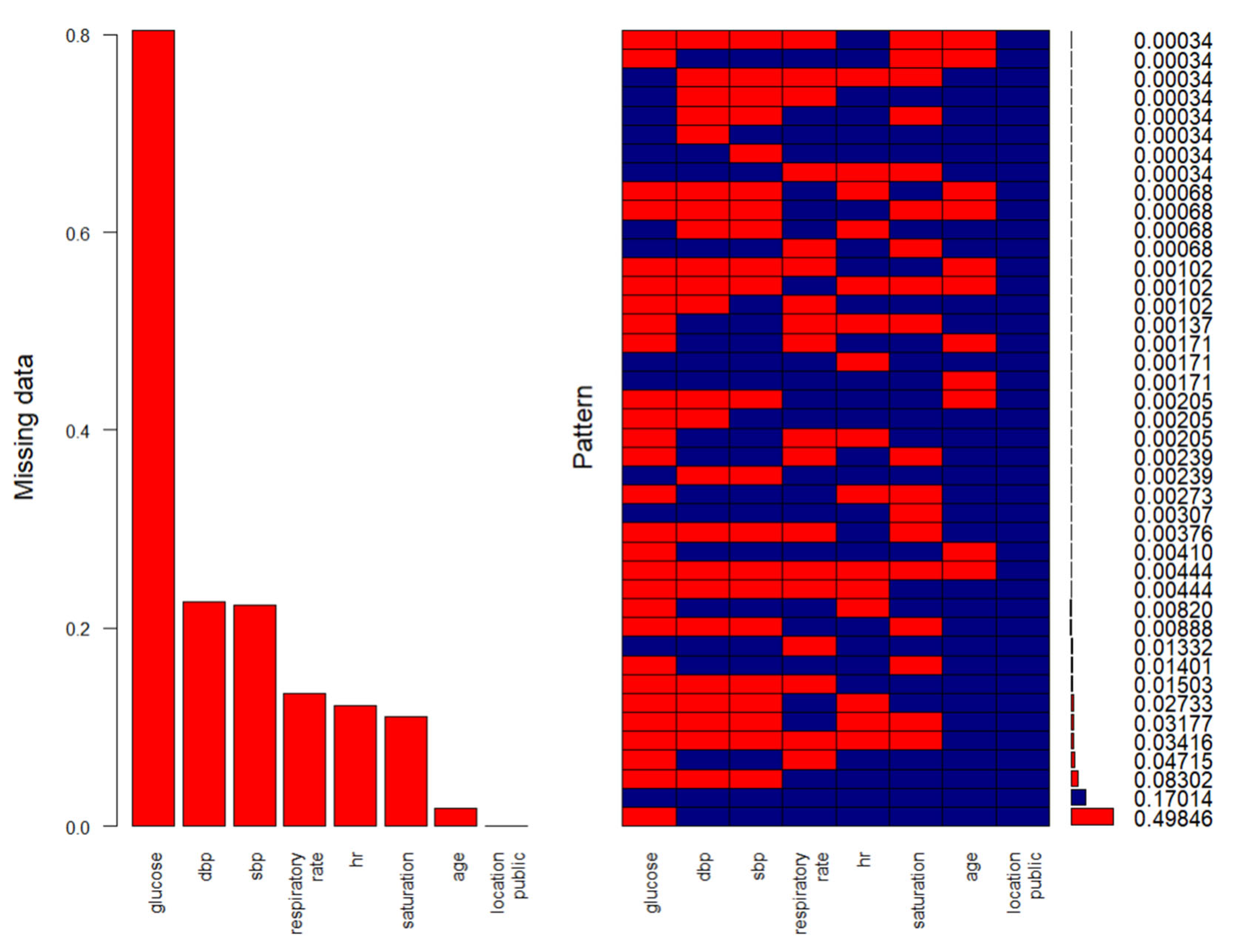

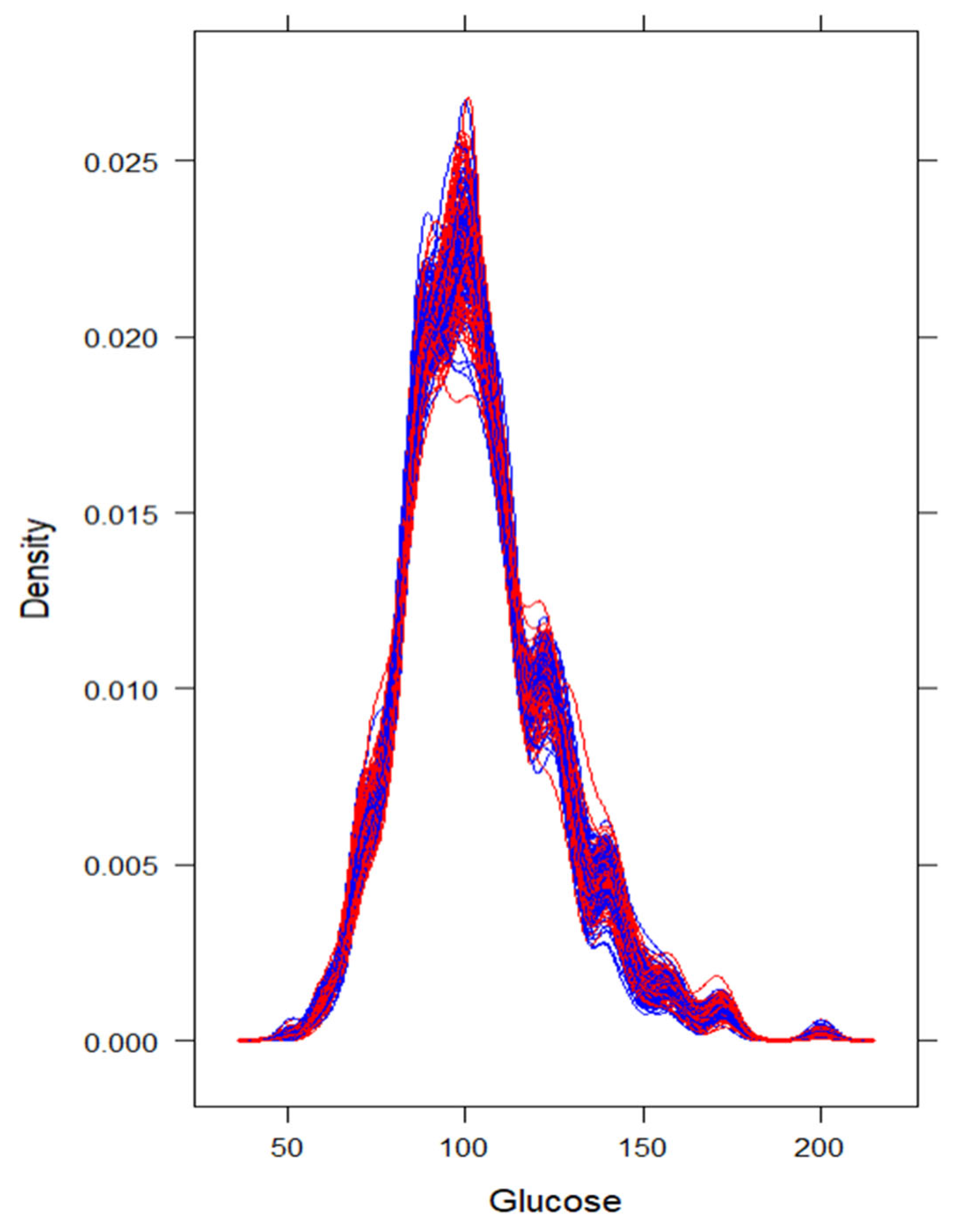

Data Preprocessing and Statistical Analysis

2.4. Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools

3. Results

3.1. Univariate Characteristics in Context of Successful Pre-Hospital Delivery, and Less-than-Normal Delivery According to the APGAR Score—Before Applying Multiple Imputation

3.2. Multivariate, Post Multiple-Imputation Modeling with Pooled Estimates Subsection

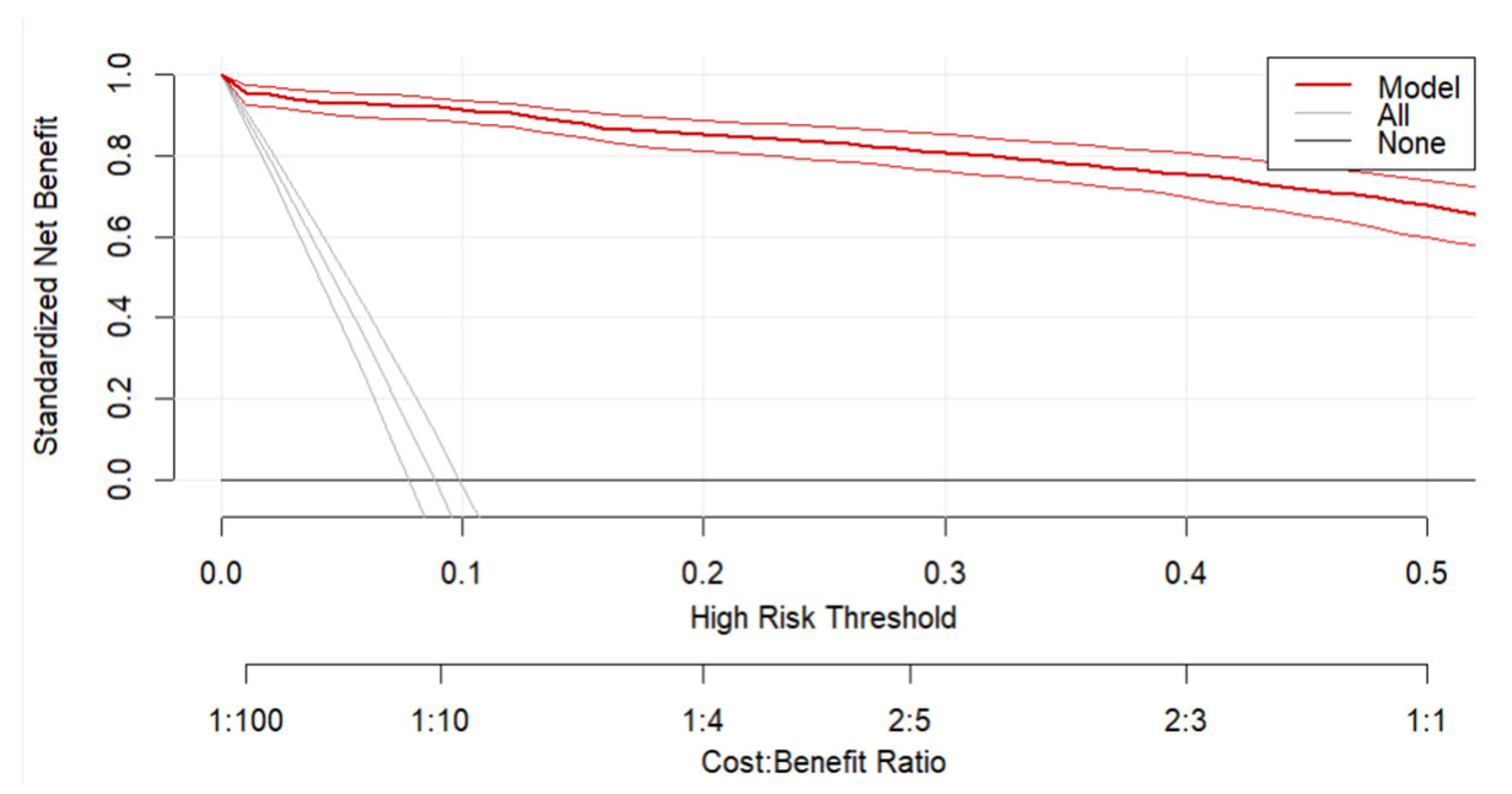

Predicting Successful Pre-Hospital Delivery

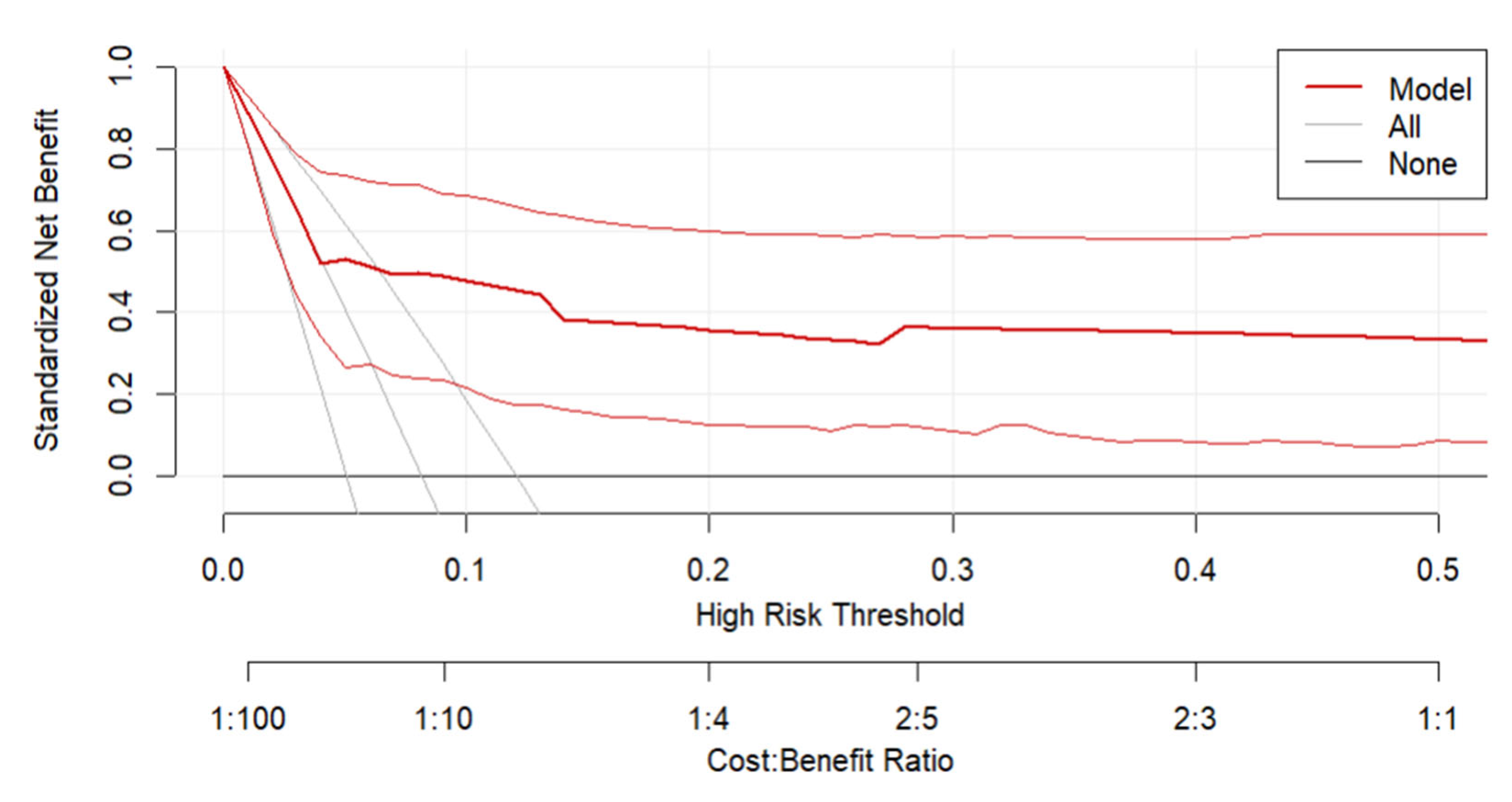

3.3. Predicting Delivery APGAR Score ≤ 7 Among All Successful Pre-Hospital Delivery

4. Discussion

Study Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BBA | Birth Before Arrival |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| DCA | Decision Curve Analysis |

| EMS | Emergency Medical Services |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| LOHS | Length of Hospital Stay |

| MICE | Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| SE | Standard Error |

References

- Giouleka, S.; Tsakiridis, I.; Kostakis, N.; Boureka, E.; Mamopoulos, A.; Kalogiannidis, I.; Athanasiadis, A.; Dagklis, T. Postnatal Care: A Comparative Review of Guidelines. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2024, 79, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcieszek, A.M.; Bonet, M.; Portela, A.; Althabe, F.; Bahl, R.; Chowdhary, N.; Dua, T.; Edmond, K.; Gupta, S.; Rogers, L.M.; et al. WHO Recommendations on Maternal and Newborn Care for a Positive Postnatal Experience: Strengthening the Maternal and Newborn Care Continuum. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e010992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhi, R.A.; Heidari, M. The Challenges of Delivery in Pre-Hospital Emergency Medical Services Ambulances in Iran: A Qualitative Study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2024, 24, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 697: Planned Home Birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 129, e117–e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIGO Committee for the Ethical Aspects of Human Reproduction and Women’s Health. Planned Home Birth. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 120, 204–205. [CrossRef]

- Approaches to Limit Intervention During Labor and Birth. Available online: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2019/02/approaches-to-limit-intervention-during-labor-and-birth (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Armstrong, J.; McDermott, P.; Saade, G.R.; Srinivas, S.K. Coding Update of the SMFM Definition of Low Risk for Cesarean Delivery from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, B2–B12.e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwanowicz-Palus, G.; Król, M. The Safety of Selected Birth Locations According to Women and Men. J. Public Health Nurs. Med. Rescue 2016, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Songül Tomar Güneysu, O.D.G. Out-of-Hospital Delivery: A Case Report. Available online: https://caybdergi.com/articles/out-of-hospital-delivery-a-case-report/doi/cayd.galenos.2021.33254 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Beaird, D.T.; Ladd, M.; Jenkins, S.M.; Kahwaji, C.I. EMS Prehospital Deliveries. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbrey, D.; Dunne, R.B.; Fales, W.; Torossian, K.; Swor, R. Describing Prehospital Deliveries in the State of Michigan. Cureus 14, e26723. [CrossRef]

- Cash, R.E.; Kaimal, A.J.; Samuels-Kalow, M.E.; Boggs, K.M.; Swanton, M.F.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Epidemiology of Emergency Medical Services-Attended out-of-Hospital Deliveries and Complications in the United States. Prehospital Emerg. Care 2024, 28, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węgrzynowska, M.; Doroszewska, A.; Witkiewicz, M.; Baranowska, B. Polish Maternity Services in Times of Crisis: In Search of Quality Care for Pregnant Women and Their Babies. Health Care Women Int. 2020, 41, 1335–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodie, V.; Thomson, A.; Norman, J. Accidental Out-of-Hospital Deliveries: An Obstetric and Neonatal Case Control Study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2002, 81, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterscheider, J.; Ma’ayeh, M.; Geary, M.P. Born before Arrival Births: Impact of a Changing Obstetric Population. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 31, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLelland, G.E.; Morgans, A.E.; McKenna, L.G. Involvement of Emergency Medical Services at Unplanned Births before Arrival to Hospital: A Structured Review. Emerg. Med. J. 2014, 31, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughney, A.; Collis, R.; Dastgir, S. Birth before Arrival at Delivery Suite: Associations and Consequences. Br. J. Midwifery 2006, 14, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, G.; Burrow, E.; McAdam, H. Babies Born in the Pre-Hospital Setting Attended by Ambulance Clinicians in the North East of England. Br. Paramed. J. 2019, 4, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvaresh-Masoud, M.; Imanipour, M.; Cheraghi, M.A. Emergency Medical Technicians’ Experiences of the Challenges of Prehospital Care Delivery During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2021, 31, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strózik, M.; Wiciak, H.; Szarpak, L.; Wroblewski, P.; Smereka, J. EMS Interventions during Planned Out-of-Hospital Births with a Midwife: A Retrospective Analysis over Four Years in the Polish Population. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, B.; Lord, B.; Barnes, M. Is Unplanned Out-of-Hospital Birth Managed by Paramedics ‘Infrequent’, ‘Normal’ and ‘Uncomplicated’? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLelland, G.; McKenna, L.; Morgans, A.; Smith, K. Epidemiology of Unplanned Out-of-Hospital Births Attended by Paramedics. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutvirtz, G.; Wainstock, T.; Landau, D.; Sheiner, E. Unplanned Out-of-Hospital Birth—Short and Long-Term Consequences for the Offspring. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnawi, A. Addressing Challenges in EMS Department Operations: A Comprehensive Analysis of Key Issues and Solution. Emerg. Care Med. 2023, 1, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strózik, M.; Wiciak, H.; Raczyński, A.; Smereka, J. Emergency Medical Team Interventions in Poland during Out-of-Hospital Deliveries: A Retrospective Analysis. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 34, 1731–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralska, A.; Puskarz-Gasowska, J.E.; Bujnowski, P.; Bokiniec, R. Use of the Expanded Apgar Score for the Assessment of Intraventricular and Intraparenchymal Haemorrhage Risk in Neonates. Ginekol. Pol. 2023, 94, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaudin, F.; Hamel, V.; Legrand, A.; Goddet, S.; Templier, F.; Potiron, C.; Pes, P.; Bagou, G.; Montassier, E. Unplanned Out-of-Hospital Birth and Risk Factors of Adverse Perinatal Outcome: Findings from a Prospective Cohort. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2019, 27, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzońca, E.; Bień, A.; Wejnarski, A.; Gotlib, J.; Bączek, G.; Gałązkowski, R.; Rzońca, P. Suspected Labour as a Reason for Emergency Medical Services Team Interventions in Poland—A Retrospective Analysis. Healthcare 2021, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, R.E.; Swor, R.A.; Samuels-Kalow, M.; Eisenbrey, D.; Kaimal, A.J.; Camargo, C.A. Frequency and Severity of Prehospital Obstetric Events Encountered by Emergency Medical Services in the United States. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combier, E.; Roussot, A.; Chabernaud, J.-L.; Cottenet, J.; Rozenberg, P.; Quantin, C. Out-of-Maternity Deliveries in France: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSisto, C.L.; Oza-Frank, R.; Goodman, D.; Conrey, E.; Shellhaas, C. Maternal Transport: An Opportunity to Improve the System of Risk-Appropriate Care. J. Perinatol. 2021, 41, 2141–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumikawa, S.; Kotani, K.; Kojo, T.; Matsubara, S.; Haruyama, S. A Nationwide Survey of Obstetric Care Status on Japan’s Islands, with Special Reference to Maternal Transport to the Mainland. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2020, 250, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzońca, E.; Bień, A.; Wejnarski, A.; Gotlib, J.; Gałązkowski, R. Polish Medical Air Rescue Interventions Concerning Pregnant Women in Poland: A 10-Year Retrospective Analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2021, 27, e933029-1–e933029-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bills, C.B.; Newberry, J.A.; Darmstadt, G.; Pirrotta, E.A.; Rao, G.V.R.; Mahadevan, S.V.; Strehlow, M.C. Reducing Early Infant Mortality in India: Results of a Prospective Cohort of Pregnant Women Using Emergency Medical Services. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamehchian, M.; Adib-Hajbaghery, M.; HeydariKhayat, N.; Rezaei, M.; Sabery, M. Primiparous Women’s Experiences of Normal Vaginal Delivery in Iran: A Qualitative Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaofe, H.; Lott, B.; Kimaru, L.; Okusanya, B.; Okechukwu, A.; Chebet, J.; Meremikwu, M.; Ehiri, J. Emergency Transportation Interventions for Reducing Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchcraft, M.L.; Ola, O.; McLaughlin, E.M.; Hade, E.M.; Murphy, A.J.; Frey, H.A.; Larrimore, A.; Panchal, A.R. A One-Year Cross Sectional Analysis of Emergency Medical Services Utilization and Its Association with Hypertension in Pregnancy. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2022, 26, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature (Quantitative) | Lack of Pre-Hospital Delivery (Total N = 2669) | Pre-Hospital Delivery (Total N = 258) | p | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % Total N | Median | Min | Max | Q1 | Q3 | N | % Total N | Median | Min | Max | Q1 | Q3 | ||

| age | 2628 | 98.4638 | 28 | 15 | 46 | 23 | 34 | 246 | 95.3488 | 30 | 16 | 44 | 25 | 34 | 0.0114 |

| respiratory rate | 2331 | 87.3361 | 16 | 12 | 20 | 14 | 18 | 204 | 79.0698 | 16 | 12 | 20 | 14 | 18 | 0.8627 |

| saturation | 2385 | 89.3593 | 98 | 90 | 100 | 98 | 99 | 218 | 84.4961 | 98 | 93 | 100 | 97 | 99 | 0.3823 |

| sbp | 2088 | 78.2315 | 130 | 70 | 180 | 120 | 140 | 186 | 72.0930 | 130 | 90 | 180 | 120 | 140 | 0.7389 |

| dbp | 2081 | 77.9693 | 80 | 40 | 130 | 70 | 85 | 184 | 71.3178 | 80 | 51 | 108 | 79 | 84 | 0.4535 |

| hr | 2354 | 88.1978 | 90 | 56 | 160 | 81 | 100 | 218 | 84.4961 | 92 | 60 | 160 | 85 | 104 | 0.0081 |

| glucose | 520 | 19.4830 | 101 | 51 | 200 | 90 | 116 | 53 | 20.5426 | 104 | 68 | 173 | 87 | 126 | 0.5733 |

| gestational week | 2669 | 100.0000 | 39 | 23 | 42 | 37 | 40 | 258 | 100.0000 | 39 | 23 | 42 | 38 | 40 | 0.0839 |

| num pregnancies | 2669 | 100.0000 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 4 | 258 | 100.0000 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 0.0020 |

| num labors | 2669 | 100.0000 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 258 | 100.0000 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 0.0018 |

| Feature (qualitative) | Lack of pre-hospital delivery | Pre-hospital delivery | p | ||||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | ||||||||||||

| location public: yes | 168 | 6.29% | 20 | 7.75% | 0.3619 | ||||||||||

| COVID-positive: no | 1504 | 56.35% | 130 | 50.39% | 0.3870 | ||||||||||

| COVID-positive: yes | 66 | 2.47% | 3 | 1.16% | |||||||||||

| COVID-positive: missing data | 1099 | 41.18% | 125 | 48.45% | |||||||||||

| multipara: yes | 1860 | 69.69% | 207 | 80.23% | 0.0004 | ||||||||||

| complications during pregnancy: yes | 473 | 17.72% | 42 | 16.28% | 0.5611 | ||||||||||

| medical care during pregnancy: yes | 2529 | 94.75% | 240 | 93.02% | 0.2399 | ||||||||||

| stage of labor: 1 | 2578 | 96.59% | 11 | 4.26% | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| stage of labor: 2 | 91 | 3.41% | 247 | 95.74% | |||||||||||

| bleeding: yes | 237 | 8.88% | 16 | 6.20% | 0.1478 | ||||||||||

| reduced fetal movement: yes | 13 | 0.49% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.5266 | ||||||||||

| lack of fetal movement: yes | 45 | 1.69% | 3 | 1.16% | 0.7075 | ||||||||||

| Rupture of membranes: no | 1425 | 53.39% | 13 | 5.04% | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| comorbidities: yes | 315 | 11.80% | 28 | 10.85% | 0.6507 | ||||||||||

| gestational diabetes: yes | 142 | 5.32% | 11 | 4.26% | 0.4665 | ||||||||||

| gestational hypertension: yes | 52 | 1.95% | 8 | 3.10% | 0.2122 | ||||||||||

| complications during labor: yes | 13 | 0.49% | 19 | 7.36% | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| neonatal status: normal | 0 | 0.00% | 237 | 91.86% | - | ||||||||||

| neonatal status: requires attention | 0 | 0.00% | 12 | 4.65% | |||||||||||

| neonatal status: needs life-saving | 0 | 0.00% | 4 | 1.55% | |||||||||||

| neonatal status: stillbirth | 0 | 0.00% | 5 | 1.94% | |||||||||||

| Feature (Quantitative) | Apgar Score ≥ 8 Pre-Hospital Delivery (Total N = 237) | Apgar Score ≤ 7 Pre-Hospital Delivery (Total N = 21) | p | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % Total N | Median | Min | Max | Q1 | Q3 | N | % Total N | Median | Min | Max | Q1 | Q3 | ||

| age | 226 | 95.3586 | 30 | 16 | 44 | 25 | 34 | 20 | 95.2381 | 31 | 21 | 40 | 26 | 35 | 0.4685 |

| respiratory rate | 190 | 80.1688 | 16 | 12 | 20 | 14 | 18 | 14 | 66.6667 | 16 | 12 | 20 | 13 | 18 | 0.7646 |

| saturation | 201 | 84.8101 | 98 | 93 | 100 | 97 | 99 | 17 | 80.9524 | 98 | 96 | 100 | 98 | 99 | 0.2613 |

| sbp | 173 | 72.9958 | 130 | 90 | 180 | 120 | 140 | 13 | 61.9048 | 130 | 96 | 156 | 120 | 140 | 0.8700 |

| dbp | 171 | 72.1519 | 80 | 51 | 108 | 75 | 84 | 13 | 61.9048 | 80 | 65 | 90 | 80 | 84 | 0.5930 |

| hr | 203 | 85.6540 | 91 | 60 | 160 | 85 | 105 | 15 | 71.4286 | 100 | 70 | 157 | 90 | 104 | 0.2979 |

| glucose | 49 | 20.6751 | 104 | 68 | 164 | 87 | 121 | 4 | 19.0476 | 114 | 93 | 173 | 97 | 150 | 0.3867 |

| gestational week | 237 | 100.0000 | 39 | 35 | 42 | 38 | 40 | 21 | 100.0000 | 36 | 23 | 41 | 33 | 39 | 0.0002 |

| num pregnancies | 237 | 100.0000 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 21 | 100.0000 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 0.9855 |

| num labors | 237 | 100.0000 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 21 | 100.0000 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 0.9372 |

| Feature (qualitative) | Apgar score ≥ 8 pre-hospital delivery | Apgar score ≤ 7 pre-hospital delivery | Fisher’s p | ||||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | ||||||||||||

| location public: yes | 18 | 7.59% | 2 | 9.52% | 0.5000 | ||||||||||

| COVID-positive: no | 118 | 49.79% | 12 | 57.14% | 0.7513 | ||||||||||

| COVID-positive: yes | 3 | 1.27% | 0 | 0.00% | |||||||||||

| COVID-positive: missing data | 116 | 48.95% | 9 | 42.86% | |||||||||||

| multipara: yes | 191 | 80.59% | 16 | 76.19% | 0.4028 | ||||||||||

| complications during pregnancy: yes | 35 | 14.77% | 7 | 33.33% | 0.0360 | ||||||||||

| medical care during pregnancy: yes | 221 | 93.25% | 19 | 90.48% | 0.4420 | ||||||||||

| stage of labor: 1 | 9 | 3.80% | 2 | 9.52% | 0.2223 | ||||||||||

| stage of labor: 2 | 228 | 96.20% | 19 | 90.48% | |||||||||||

| bleeding: yes | 15 | 6.33% | 1 | 4.76% | 0.6189 | ||||||||||

| reduced fetal movement: yes | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | - | ||||||||||

| lack of fetal movement: yes | 1 | 0.42% | 2 | 9.52% | 0.0181 | ||||||||||

| Rupture of membranes: no | 10 | 4.22% | 3 | 14.29% | 0.0782 | ||||||||||

| comorbidities: yes | 26 | 10.97% | 2 | 9.52% | 0.5955 | ||||||||||

| gestational diabetes: yes | 10 | 4.22% | 1 | 4.76% | 0.6146 | ||||||||||

| gestational hypertension: yes | 7 | 2.95% | 1 | 4.76% | 0.4979 | ||||||||||

| complications during labor: yes | 19 | 8.02% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.1873 | ||||||||||

| neonatal status: normal | 237 | 100.00% | 0 | 0.00% | - | ||||||||||

| neonatal status: requires attention | 0 | 0.00% | 12 | 57.14% | |||||||||||

| neonatal status: needs life-saving | 0 | 0.00% | 4 | 19.05% | |||||||||||

| neonatal status: stillbirth | 0 | 0.00% | 5 | 23.81% | |||||||||||

| Feature | Interpretation | β | β SE | t | df | p | OR | OR −95% CI | OR 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | Baseline odds of pre-hospital delivery given, rupture od membranes, no complications during labor, HR = 90 bpm, no medical care during pregnancy, one past pregnancy, and first stage of labor | −5.5587 | 0.5135 | −10.8258 | 2908.9340 | <0.0001 | 0.0039 | 0.0014 | 0.0105 |

| rupture of membranes: yes vs no | Fold difference in baseline odds between patients with intact membranes vs. rupture of membranes | −2.1573 | 0.3565 | −6.0506 | 2915.9180 | <0.0001 | 0.1156 | 0.0575 | 0.2326 |

| complications during labor: yes | Fold difference in baseline odds between patients with complications during labor vs. no complications | 0.8653 | 0.7427 | 1.1650 | 2912.8240 | 0.2441 | 2.3757 | 0.5541 | 10.1869 |

| HR (median–centered) | Fold difference in baseline odds with each 1 bpm increase in HR | 0.0149 | 0.0086 | 1.7326 | 2115.4620 | 0.0833 | 1.0150 | 0.9980 | 1.0323 |

| medical care during pregnancy: yes vs no | Fold difference in baseline odds between patients with medical care during pregnancy vs. those without it | 0.7607 | 0.4168 | 1.8251 | 2913.7360 | 0.0681 | 2.1397 | 0.9453 | 4.8432 |

| number of pregnancies (median-centered) | Fold difference in baseline odds with each subsequent pregnancy | −0.1468 | 0.0622 | −2.3600 | 2914.2590 | 0.0183 | 0.8634 | 0.7643 | 0.9754 |

| stage of labor:2 | Fold difference in baseline odds between patients at the second stage of labor vs. first | 6.2818 | 0.3427 | 18.3291 | 2912.2240 | <0.0001 | 534.7309 | 273.1524 | 1046.8043 |

| Feature | Interpretation | β | β SE | t | df | p | OR | OR −95% CI | OR 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | Baseline odds neonatal status according to the APGAR score ≤ 7 given successful pre-hospital delivery, assuming 39th gestational week and presence of any fetal movement | −3.2687 | 0.3550 | −9.2066 | 252.9980 | <0.0001 | 0.0381 | 0.0190 | 0.0763 |

| gestational week (median- centered) | Fold change in baseline odds with each one gestational week increase | −0.5880 | 0.1377 | −4.2709 | 252.9980 | <0.0001 | 0.5554 | 0.4241 | 0.7275 |

| lack of fetal movement: yes vs no | Fold change in baseline odds between cases of lack of fetal movement vs. any movement (normal or reduced) | 3.2718 | 1.4553 | 2.2482 | 252.9980 | 0.0254 | 26.3578 | 1.5211 | 456.7256 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wach, J.; Lewandowski, Ł.; Staniczek, J.; Czapla, M. When Every Minute Counts: Predicting Pre-Hospital Deliveries and Neonatal Risk in Emergency Medical Services Using Data-Driven Models. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 941. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030941

Wach J, Lewandowski Ł, Staniczek J, Czapla M. When Every Minute Counts: Predicting Pre-Hospital Deliveries and Neonatal Risk in Emergency Medical Services Using Data-Driven Models. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):941. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030941

Chicago/Turabian StyleWach, Joanna, Łukasz Lewandowski, Jakub Staniczek, and Michał Czapla. 2026. "When Every Minute Counts: Predicting Pre-Hospital Deliveries and Neonatal Risk in Emergency Medical Services Using Data-Driven Models" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 941. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030941

APA StyleWach, J., Lewandowski, Ł., Staniczek, J., & Czapla, M. (2026). When Every Minute Counts: Predicting Pre-Hospital Deliveries and Neonatal Risk in Emergency Medical Services Using Data-Driven Models. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 941. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15030941