Photobiomodulation Therapy in the Management of Orofacial Neuropathic Pain—WALT Position Paper 2026

Disclaimer

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

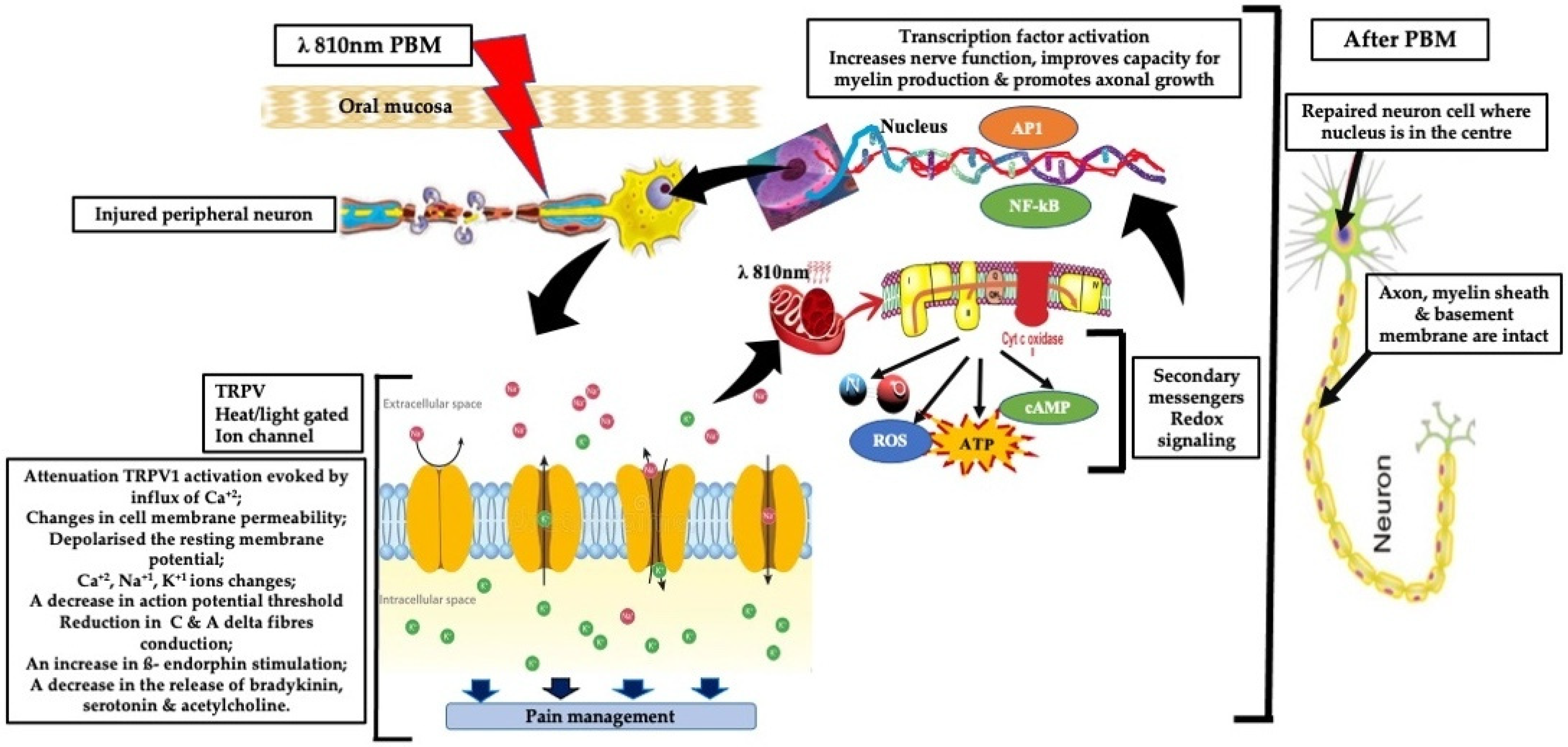

1.2. Mechanistic Basis of PBM in Neuropathic Pain

- Neuroprotection and regeneration: PBM upregulates neurotrophic factors like nerve growth factor (NGF) and supports axonal repair, which are crucial for peripheral nerve regeneration [14].

- Analgesic modulation: PBM modulates nociceptive signaling via effects on ion channels (e.g., TRPV1) and peripheral nerve excitability. Experimental animal and ex vivo studies show that, under specific irradiation conditions, PBM can transiently reduce action potential amplitudes and alter fast axonal transport in small-diameter A∂ and C fibers, leading to reduced nociceptive signaling propagation. These effects are neuromodulatory, parameter-dependent, and reversible, and at clinically applied, non-thermal doses, analgesia is more likely mediated by modulation of nerve function and inflammatory pathways rather than true conduction block [15,16,17].

- A third mechanism involving activation of extracellular latent TGF-β1 has been noted, which is primarily responsible for the tissue resilience, healing, and regeneration [18].

- Central modulation and thermoregulation: Functional imaging studies suggest PBM may influence central pain processing and reduce neurogenic inflammation [19].

1.3. Relevance to Orofacial Neuropathic Pain

- Primary BMS:

- TN is primarily peripheral at onset, usually due to neurovascular compression, with central sensitization developing in chronic cases.

- PHN begins with peripheral nerve injury, which often shows early central involvement.

- PTTN is mainly peripheral, with a central mechanism emerging in persistent pain.

- GPN and ON are predominantly peripheral, though central sensitization can occur in prolong cases.

1.4. Limitations of Current Treatments for Neuropathic Pain

- Incomplete or inconsistent pain relief: Pharmacological treatments for NP often provide only partial analgesia, with substantial inter-individual variability. While certain conditions (e.g., TN) may initially respond well to specific agents, sustained pain control is often difficult to maintain over time, and long-term efficacy remains limited for a substantial proportion of patients.

- Adverse effect profiles: Many first-line agents are associated with dose-limiting adverse effects, including sedation, dizziness, cognitive impairment, and dry mouth, which can compromise tolerability, adherence, and overall QoL. The clinical impact of these effects varies across NP subtypes and patient populations.

- Risk of tolerance, dependence, and misuse: Opioid therapies, in particular, pose risks of tolerance development, physical dependence, and misuse, limiting their suitability for long-term management of chronic NP and raising important safety concerns.

- Lack of disease-modifying or regenerative effects: Current pharmacological treatments primarily provide symptomatic relief and do not promote neuronal repair or address underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, thereby failing to alter disease progression across NP conditions.

- Variable efficacy in conditions involving central sensitization: In NP states characterized by central sensitization, conventional pharmacotherapies often demonstrate reduced effectiveness, as they inadequately target the central neural mechanisms sustaining chronic pain.

1.5. Aims and Objectives

- To systematically review and synthesize the available evidence supporting PBM use in orofacial neuropathies.

- To critically appraise the clinical effectiveness of PBM in managing orofacial neuropathic pain (ONP).

- To establish the level of evidence (LoE) for PBM effectiveness in the included ONP conditions.

- To identify gaps in current research and propose directions for standardization and future investigations.

- To formulate WALT recommendations based on Clinical Practice Guidelines and Expert Consensus Opinions, explicitly reflecting the strength and quality of the underlying evidence.

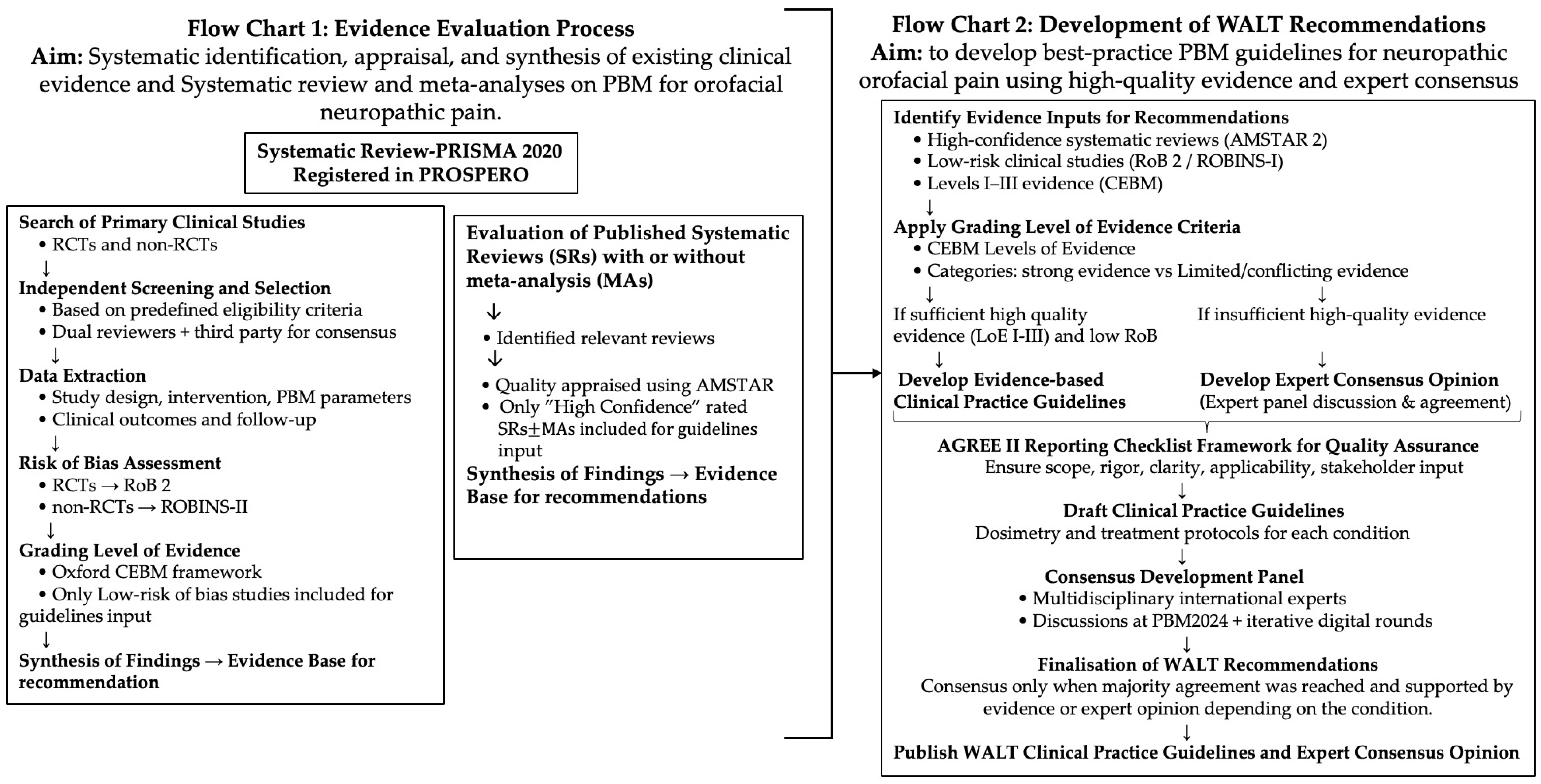

2. Evidence Evaluation and HANNA Framework

2.1. Evidence Evaluation and Quality Assessment

2.2. Scientific Rationale and Novelty of the HANNA Framework

3. Materials and Methods

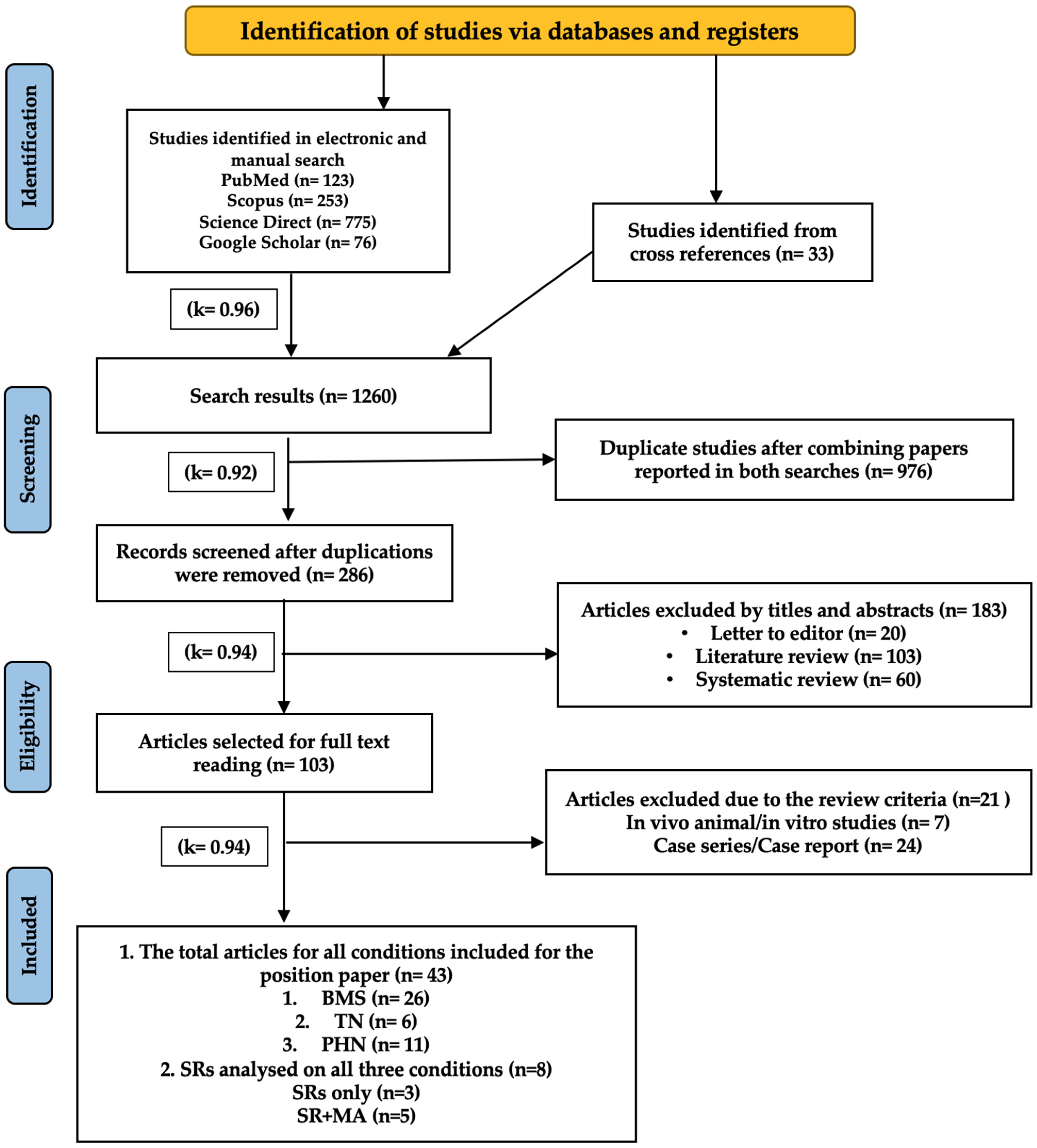

3.1. Evaluation of the Existing Evidence for Systematic Review

3.1.1. Primary Clinical Studies

3.1.2. Search Strategy

“Photobiomodulation” OR “PBM” OR “low-level laser therapy” OR “LLLT”

AND

“Orofacial neuropathic pain” OR “neuropathic orofacial pain” OR “trigeminal neuralgia” OR “idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia” OR “primary burning mouth syndrome” OR “post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy” OR “trigeminal nerve injury” OR “BMS” OR “PHN” OR “post-herpetic neuralgia”, OR “glossopharyngeal neuralgia” OR “neuropathic pain” OR “occipital neuralgia” OR “Burning sensation” OR “BMS” OR “GPN” OR “ON” OR “PTTN” OR “TN”.

3.1.3. Data Extraction

3.1.4. Eligibility Criteria

- Inclusion Criteria

- Human RCTs and NRCTs evaluating PBM therapy in patients diagnosed with NP in the following orofacial conditions: primary BMS, idiopathic TN, PHN, PTTN, GPN, and ON.

- Studies reporting pain outcomes, functional recovery, or QoL metrics.

- Articles published in English.

- Studies reporting PBM parameters and treatment protocols.

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on PBM evaluation in the management of NP.

- Peer-reviewed papers published up to March 2025.

- Exclusion Criteria

- In vitro and in vivo animal studies.

- Case series, retrospective, case reports, or short communications.

- Studies focused on NP induced by neurodegenerative conditions and oncology treatments.

- Studies investigating PBM for trigeminal nerve (V) regeneration or neurosensory recovery, rather than for NP.

- Any other orofacial conditions-induced pain and unrelated to NP.

- Studies involving combined cohorts of various orofacial pain conditions.

- Studies without a clear methodology or intervention details.

- Studies focused exclusively on non-NP.

- Studies focused on tumor or infection-induced NP.

3.1.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.1.6. Level of Evidence and Grading Framework

3.2. Evaluation of the Current Published Systematic Reviews

3.3. Development of WALT Guidelines and Recommendations

3.3.1. Consensus and Grading Process

- High confidence of existing SRs MAs of RCTs appraised using the AMSTAR 2 tool (LoE I according to CEBM);

- Systematic review (PRISMA 2020) of low-risk-of-bias clinical studies, RCTs, and NRCTs, assessed using RoB 2 and ROBINS-I, respectively, and graded as Level II or III evidence, respectively, according to the Oxford CEBM–LoE framework.

3.3.2. AGREE II Checklist Adaptation

3.4. Consensus Development Panel

4. Results

4.1. Summary Assessment of All Included Studies and Published Reviews

4.2. Assessment of Evidence from Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis in BMS

4.3. Assessment of Evidence of Included Studies for Each Orofacial Neuropathic Condition

4.3.1. Primary Burning Mouth Syndrome

- WALT Recommendation: Clinical Practice Guidelines

4.3.2. Idiopathic Trigeminal Neuralgia

- WALT Recommendation: Expert Consensus Opinion

4.3.3. Post-Herpetic Neuralgia

- WALT Recommendation: Expert Consensus Opinion

4.3.4. Post-Traumatic Trigeminal Neuralgia (PTTN)

4.3.5. Glossopharyngeal (GPN) and Occipital Neuralgia (ON)

5. Path Forward for Advancing PBM Research in Orofacial Neuropathic Pain

- Standardized and Complete Dosimetry Reporting

- Verification of Delivered Dose

- Choice of Light Source

- Condition-Specific Protocols

- Pathophysiology-Informed Application

- Anatomical Precision in Treatment Delivery

- Thermographic Monitoring During PBM

- Improved Study Design

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jensen, T.S.; Baron, R.; Haanpää, M.; Kalso, E.; Loeser, J.D.; Rice, A.S.C.; Treede, R.D. A new definition of neuropathic pain. Pain 2011, 152, 2204–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhassira, D.; Lantéri-Minet, M.; Attal, N.; Laurent, B.; Touboul, C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain 2008, 136, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnerup, N.B.; Attal, N.; Haroutounian, S.; McNicol, E.; Baron, R.; Dworkin, R.H.; Gilron, I.; Haanpää, M.; Hansson, P.; Jensen, T.S.; et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuser, W.; Petzke, F.; Radbruch, L.; Tölle, T.R. The opioid epidemic and the need for pain medicine. Pain Rep. 2019, 4, e769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.; Dalvi, S.; Bensadoun, R.J.; Benedicenti, S. Role of Photobiomodulation Therapy in Modulating Oxidative Stress in Temporomandibular Disorders. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Human Randomised Controlled Trials. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Muñoz, A.; Cuevas-Cervera, M.; Pérez-Montilla, J.J.; Aguilar-Núñez, D.; Hamed-Hamed, D.; Aguilar-García, M.; Pruimboom, L.; Navarro-Ledesma, S. Efficacy of Photobiomodulation Therapy in the Treatment of Pain and Inflammation: A Literature Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.; Dai, T.; Sharma, S.K.; Huang, Y.Y.; Carroll, J.D.; Hamblin, M.R. The nuts and bolts of low-level laser (light) therapy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocot-Kępska, M.; Dobrogowski, J.; Zajaczkowska, R.; Wordliczek, J.; Mika, J.; Przeklasa-Muszynska, A. Topical treatments and their molecular/cellular mechanisms in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain—Narrative review. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R. Mechanisms and applications of the anti-inflammatory effects of photobiomodulation. AIMS Biophys. 2017, 4, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karu, T. Mitochondrial mechanisms of photobiomodulation in context of new data about multiple roles of ATP. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2010, 28, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.; Bensadoun, R.J.; Beken, S.V.; Burton, P.; Carroll, J.; Benedicenti, S. Outpatient Oral Neuropathic Pain Management with Photobiomodulation Therapy: A Prospective Analgesic Pharmacotherapy-Paralleled Feasibility Trial. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Sharma, S.K.; Carroll, J.D.; Hamblin, M.R. Biphasic dose response in low-level light therapy. Dose-Response 2011, 9, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.Q.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.H.; Chen, S.P.; Li, M.; Shahveranov, A.; Ye, D.W.; Tian, Y.K. Interleukin-6: An emerging regulator of pathological pain. J. Neuroinflamm. 2016, 13, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehpour, F.; Cassano, P.; Chang, S.F.; Hamblin, M.R. Near-infrared photobiomodulation in depression and anxiety. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1269, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Chow, R.; Armati, P.J. Inhibitory effects of visible 650-nm and infrared 808-nm laser irradiation on somatosensory and compound muscle action potentials in rat sciatic nerve: Implications for laser-induced analgesia. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2011, 16, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, R.; David, M.; Armati, P. 830-nm laser irradiation induces varicosity formation, reduces mitochondrial membrane potential and blocks fast axonal flow in small and medium diameter rat dorsal root ganglion neurons: Implications for the analgesic effects of 830-nm laser. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2007, 12, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, R.; Armati, P.; Laakso, E.L.; Bjordal, J.M.; Baxter, G.D. Inhibitory effects of laser irradiation on peripheral mammalian nerves and relevance to analgesic effects: A systematic review. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2011, 29, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arany, P.R. Photobiomodulation-Activated Latent Transforming Growth Factor-β1: A Critical Clinical Therapeutic Pathway and an Endogenous Optogenetic Tool for Discovery. Photobiomodul Photomed. Laser Surg. 2022, 40, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairuz, T.; Cho, S.; Lee, J.H. Photobiomodulation therapy on brain: Pioneering an innovative approach to revolutionize cognitive dynamics. Cells 2024, 13, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasser, G.D.; Epstein, J.B.; Grushka, M. Burning mouth syndrome: Recognition, understanding, and management. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 20, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewska, J.M. Trigeminal neuralgia. BMJ Clin. Evid. 2014, 2014, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.L.; Raja, S.N. Treatment of acute postoperative pain. Lancet 2011, 377, 2215–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerfield, M.R.; Einhaus, K.; Hagerty, K.L.; Brouwers, M.C.; Seidenfeld, J.; Lyman, G.H. American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines: Opportunities and Challenges. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4022–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Levels of Evidence (March 2009). University of Oxford. Available online: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kerkvliet, K.; Spithoff, K.; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. The AGREE reporting checklist: A tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016, 352, i1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves-Pereira, T.C.; Rawat, N.; Bensadoun, R.J.; Arany, P.R.; Santos-Silva, A.R. How do clinicians prescribe photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT)? Harmonizing PBMT dosing with photonic fluence and Einstein. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2024, 138, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, A.M.C.; Biasotto-Gonzalez, D.A.; Kohatsu, E.Y.I.; de Oliveira, S.S.I.; Bussadori, S.K.; Tanganeli, J.P.C. Photobiomodulation on trigeminal neuralgia: Systematic review. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, L.A.; Oliveira, P.A.; Karuline, S.C.L.; de Oliveira, G.P.S.; Monteiro, A.J.; Souza, F.V.; Lopes Falcão, M.M. Effectiveness of Photobiomodulation in Pain Associated With Burning Mouth Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Res. Soc. Dev. 2025, 14, e3614248159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pedro, M.; López-Pintor, R.M.; de la Hoz-Aizpurua, J.L.; Casañas, E.; Hernández, G. Efficacy of Low-Level Laser Therapy for the Therapeutic Management of Neuropathic Orofacial Pain: A Systematic Review. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2020, 34, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, R.; Dalvi, S.; Bensadoun, R.J.; Raber-Durlacher, J.E.; Benedicenti, S. Role of Photobiomodulation Therapy in Neurological Primary Burning Mouth Syndrome. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Human Randomised Controlled Clinical Trials. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuhara, M.R.; Trevisani, V.F.M.; Macedo, C.R. Effects of Photobiomodulation on Burning Mouth Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 2025, 52, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camolesi, G.C.V.; Marichalar-Mendía, X.; Padín-Iruegas, M.E.; Spanemberg, J.C.; López-López, J.; Blanco-Carrión, A.; Gándra-Via, P.; Gllas-Torreira, M.; Pérez-Sayáns, M. Efficacy of photobiomodulation in reducing pain and improving the quality of life in patients with idiopathic burning mouth syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 2123–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, L.; Zhao, W.; Yan, Z. Effectiveness of photobiomodulation in the treatment of primary burning mouth syndrome-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Jiang, W.-W. Low-level laser treatment of burning mouth syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oral Maxillofac. Med. 2019, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pedro, M.; López-Pintor, R.M.; Casañas, E.; Hernández, G. Effects of photobiomodulation with low-level laser therapy in burning mouth syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Oral Dis. 2020, 26, 1764–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardellini, E.; Amadori, F.; Conti, G.; Majorana, A. Efficacy of the photobiomodulation therapy in the treatment of the burning mouth syndrome. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2019, 24, e787–e791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugaya, N.N.; Silva, É.F.; Kato, I.T.; Prates, R.; Gallo, C.B.; Pellegrini, V.D. Low Intensity laser therapy in patients with burning mouth syndrome: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Braz. Oral Res. 2016, 30, e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduino, P.G.; Cafaro, A.; Garrone, M.; Gambino, A.; Cabras, M.; Romagnoli, E.; Broccoletti, R. A randomized pilot study to assess the safety and the value of low-level laser therapy versus clonazepam in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Lasers Med Sci. 2016, 31, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zhou, X.; Yang, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Huang, Z.; Du, Q.; Tang, G. Efficacy and safety of photobiomodulation combined with oral cryotherapy on oral mucosa pain in patients with burning mouth syndrome: A multi-institutional, randomized, controlled trial. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.L.; Sun, C.; Zhao, R.; Wang, H.Y.; Jiang, W.W. Comparative efficacy of low-level diode laser therapy with different wavelengths in burning mouth syndrome: A randomized, single-blind trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, A.G.; Lopez-Jornet, P.; Pardo Marin, L.; Pons-Fuster, E.; Tvarijonaviciute, A. Burning Mouth Syndrome Treated with Low-Level Laser and Clonazepam: A Randomized, Single-Blind Clinical Trial. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, N.G.; Gonzaga, A.K.G.; de Sena Fernandes, L.L.; da Fonseca, A.G.; Queiroz, S.I.M.L.; Lemos, T.M.A.M.; da Silveira, É.J.D.; de Medeiros, A.M.C. Evaluation of laser therapy and alpha-lipoic acid for the treatment of burning mouth syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbabi-Kalati, F.; Bakhshani, N.M.; Rasti, M. Evaluation of the efficacy of low-level laser in improving the symptoms of burning mouth syndrome. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2015, 7, e524–e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, C.K.S.; Serrão, M.D.C.P.N.; de Lima, A.A.S.; da Silveira, É.J.D.; de Oliveira, P.T. Comparative analysis of photobiomodulation therapy and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for burning mouth: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Invesig. 2023, 27, 6157–6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lončar-Brzak, B.; Škrinjar, I.; Brailo, V.; Vidović-Juras, D.; Šumilin, L.; Andabak-Rogulj, A. Burning Mouth Syndrome (BMS)-Treatment with Verbal and Written Information, B Vitamins, Probiotics, and Low-Level Laser Therapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardina, G.A.; Casella, S.; Bilello, G.; Messina, P. Photobiomodulation Therapy in the Management of Burning Mouth Syndrome: Morphological Variations in the Capillary Bed. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Škrinjar, I.; Lončar Brzak, B.; Vidranski, V.; Vučićević Boras, V.; Rogulj, A.A.; Pavelić, B. Salivary Cortisol Levels and Burning Symptoms in Patients with Burning Mouth Syndrome before and after Low Level Laser Therapy: A Double Blind Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2020, 54, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanemberg, J.C.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Rodríguez-de Rivera-Campillo, E.; Jané-Salas, E.; Salum, F.G.; López-López, J. Low-level laser therapy in patients with Burning Mouth Syndrome: A double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, e162–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, M.; Včev, A.; Siber, S.; Vučićević Boras, V.; Rotim, Ž.; Matijević, M. The Efficacy of Low-Level Laser Therapy in Burning Mouth Syndrome—A Pilot Study. Acta Clin. Croat. 2018, 57, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanemberg, J.C.; López López, J.; de Figueiredo, M.A.; Cherubini, K.; Salum, F.G. Efficacy of low-level laser therapy for the treatment of burning mouth syndrome: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Biomed. Opt. 2015, 20, 098001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezelj-Ribarić, S.; Kqiku, L.; Brumini, G.; Urek, M.M.; Antonić, R.; Kuiš, D.; Glažar, I.; Städtler, P. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in saliva in patients with burning mouth syndrome before and after treatment with low-level laser therapy. Lasers Med. Sci. 2013, 28, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, J.M.; Nunes, T.; Almiro, P.A.; Figueiredo, J.; Corte-Real, A. Long-Term Benefits of Photobiomodulation Therapy on Health-Related Quality of Life in Burning Mouth Syndrome Patients: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, L.D.F.C.; de Andrade, S.C.; Nogueira, G.E.; Leão, J.C.; de Freitas, P. Phototherapy on the Treatment of Burning Mouth Syndrome: A Prospective Analysis of 20 Cases. Photochem. Photobiol. 2015, 91, 1231–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, S.; Lopez-Jornet, P. Effects of low-level laser therapy on burning mouth syndrome. J. Oral Rehabil. 2017, 44, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finfter, O.; Kizel, L.; Czerninski, R.; Heiliczer, S.; Sharav, Y.; Cohen, R.; Aframian, D.J.; Haviv, Y. Photobiomodulation alleviates Burning Mouth Syndrome pain: Immediate and weekly outcomes explored. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 4668–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotta, B.M.; Sugaya, N.N.; Hanna, R.; Gallo, C.B. Efficacy of 660 nm Photobiomodulation in Burning Mouth Syndrome Management: A Single-Blind Quasi-Experimental Controlled Clinical Trial. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2024, 42, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.W.; Huang, Y.F. Treatment of burning mouth syndrome with a low-level energy diode laser. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2011, 29, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, U.; Del Vecchio, A.; Capocci, M.; Maggiore, C.; Ripari, M. The low level laser therapy in the management of neurological burning mouth syndrome. A pilot study. Ann. Stomatol. 2010, 1, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, W.; Li, S.; Lu, Q.; Wang, J.; Tao, X. The immediate pain relief of low-level laser therapy for burning mouth syndrome: A retrospective study of 94 cases. Front. Oral Health 2024, 5, 1458329, Erratum in Front. Oral Health 2025, 6, 1657781. https://doi.org/10.3389/froh.2025.1657781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagözoğlu, İ.; Demirkol, N.; Parlar Öz, Ö.; Keçeci, G.; Çetin, B.; Özcan, M. Clinical Efficacy of Two Different Low-Level Laser Therapies for the Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Azab, I.M.; Abo Elyazed, T.I.; El Gendy, A.M.; Abdelmonem, A.F.; Abd El-Hakim, A.A.; Sheha, S.M.; Mohammed, A.H. Effect of electromagnetic therapy versus low-level laser therapy on diabetic patients with trigeminal neuralgia: A randomized control trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 59, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, H.; Najafi, S.; Khayamzadeh, M.; Zahedi, A.; Mahdavi, A. Therapeutic and Analgesic Efficacy of Laser in Conjunction With Pharmaceutical Therapy for Trigeminal Neuralgia. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 9, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammadi, D.; Amirnaseri, R.; Peirovifar, A.; Hossainzadeh, H.; Eidi, M.; Ehsaei, M.; Ehsaei, M.; Vahedi, P. Gasserian Ganglion Block With or Without Low-intensity Laser Therapy in Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Comparative Study. Neurosurg. Q. 2012, 22, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckerdal, A.; Bastian, L. Can low reactive-level laser therapy be used in the treatment of neurogenic facial pain? A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of patients with trigeminal neuralgia. Laser Ther. 1996, 8, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.B.; Akhanjee, L.K.; Cooney, M.M.; Goldstein, J.; Tamzyoshi, S.; Segal-Gidan, F. Laser Therapy for Pain of Trigeminal Neuralgia. Clin. J. Pain. 1987, 3, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, R.; Fazal, M.U.; Saleem, M.; Saleem, S. Role of low-level laser therapy in post-herpetic neuralgia: A pilot study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 35, 1759–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.Y.; Han, T.Y.; Kim, I.S.; Yeo, I.K.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, M.N. The Effects of 830 nm Light-Emitting Diode Therapy on Acute Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus: A Pilot Study. Ann. Dermatol. 2013, 25, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.S.; Dewan, S.P.; Kaur, A.; Kumar, P.; Dhawan, A.K. Role of laser therapy in post herpetic neuralgia. Indian. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 1999, 65, 134–136. [Google Scholar]

- Toshikazu, H.; Osamu, K.; Hiroshi, O.; Rie, N.; Yoshihiro, O. Efficacy of laser irradiation on the area near the stellate ganglion is dose-dependent: A double-blind crossover placebo-controlled study. Laser Ther. 1997, 9, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiromichi, Y.; Hideoki, O. Comparative study of 60 mw diode laser therapy and 150 mW diode laser therapy in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Laser Ther. 1995, 7, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, K.; Shimoyama, N.; Shimoyama, M.; Mizuguchi, T. Evaluation of analgesic effect of low-power He:Ne laser on postherpetic neuralgia using VAS and modified McGill pain questionnaire. J. Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 1991, 9, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemmostsu, O.; Sato, K.; Furumido, H.; Harada, K.; Takigawa, C.; Kaseno, S.; Yokota, S.; Hanaoka, Y.; Yamamura, T. Efficacy of low reactive-level laser therapy for pain attenuation of postherpetic neuralgia. Laser Ther. 1991, 3, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S.; McKibbin, R.D. Treatment of post herpetic neuralgia using a 904 nm (infrared) low incident energy laser: A clinical study. Laser Ther. 1991, 3, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.N.; Kim, T.H.; Lim, S.D. Clinical trial of low reactive-level laser therapy in 20 patients with postherpetic neuralgia. Laser Ther. 1990, 2, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, K.; Shimoyama, N.; Shimoyama, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Shimizu, T.; Mizuguchi, T. Effect of repeated irradiation of low-power He-Ne laser in pain relief from postherpetic neuralgia. Clin. J. Pain. 1989, 5, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.C.; Naru, S.H.; Parswanath, S.K.; Copparam, J.; Ohshiro, T. A double-blind crossover trial of low-level laser therapy in the treatment of post herpetic neuralgia. Laser Ther. 1989, 1, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Srivastava, A.; Batra, S.; Pal, S.; Darjee, S.; Shekhar, A. Adjunctive 810 nm photobiomodulation with pharmacotherapy for trigeminal neuralgia: A randomized controlled trial in a tertiary care centre. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2025, 272, 113249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, P.A.; Carroll, J.D. How to report low-level laser therapy (LLLT)/photomedicine dose and beam parameters in clinical and laboratory studies. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2011, 29, 785–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, R.; Agas, D.; Benedicenti, S.; Laus, F.; Cuteri, V.; Sabbieti, M.G.; Amaroli, A. A comparative study between the effectiveness of 980nm photobiomodulation, delivered by Gaussian versus flattop profiles on osteoblasts maturation Frontier in Endocrinology. Bone Res. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaroli, A.; Benedicenti, S.; Bianco, B.; Bosco, A.; Clemente, M.R.V.; Hanna, R.; Kalarickel Ramakrishnan, P.; Raffetto, M.; Ravera, S. Electromagnetic Dosimetry for Isolated Mitochondria Exposed to Near-Infrared Continuous-Wave Illumination in Photobiomodulation Experiments. Bioelectromagnetics 2021, 42, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadis, M.A.; Zainal, S.A.; Holder, M.J.; Carroll, J.D.; Cooper, P.R.; Milward, M.R.; Palin, W.M. The dark art of light measurement: Accurate radiometry for low-level light therapy. Lasers Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, V.; Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation: Lasers vs. light emitting diodes? Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 17, 1003–1017, Erratum in Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 18, 259. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8pp90049c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmello, J.C.; Barbugli, P.A.; Jordão, C.C.; Oliveira, R.; Pavarina, A.C. The biological effects of different LED wavelengths in the health field. A review. Rev. Odontol. UNESP 2023, 52, e20230028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedford, C.E.; DeLapp, S.; Jacques, S.; Anders, J. Quantitative Analysis of Transcranial and Intraparenchymal Light Penetration in Human Cadaver Brain Tissue. Lasers Surg. Med. 2015, 47, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holanda, V.M.; Chavantes, M.C.; Wu, X.; Anders, J.J. The mechanistic basis for photobiomodulation therapy of neuropathic pain by near infrared laser light. Lasers Surg. Med. 2017, 49, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, W.; Jin, S.; Piao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Li, N.; Yao, H. Infrared thermography in clinical practice: A literature review. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arany, P.R. Photobiomodulation therapy. JADA 2025, 4, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensadoun, R.J.; Epstein, J.B.; Nair, R.G.; Barasch, A.; Raber-Durlacher, J.E.; Migliorati, C.; Genot-Klastersky, M.T.; Treister, N.; Arany, P.; Lodewijckx, J.; et al. World Association for Laser Therapy (WALT). Safety and efficacy of photobiomodulation therapy in oncology: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 8279–8300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/topic-selection/gid-ipg10373 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

| Level | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Evidence from at least one properly designed randomized controlled trial (RCT) or meta-analysis of RCTs. |

| II | Evidence from well-designed non-randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, or case-control studies. |

| III | Evidence based on expert opinion, clinical experience, descriptive studies, or case reports. |

| IV | Evidence from multiple time series or dramatic results in uncontrolled experiments. |

| V | Evidence from Expert committee reports, clinical experience, or descriptive studies. |

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Evidence from a systematic review of all relevant randomized controlled trials (RCT’s), or evidence-based clinical practice guidelines based on systematic reviews of RCT’s |

| II | Evidence obtained from at least one well-designed randomized controlled trial (RCT) |

| III | Evidence obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomization, quasi-experimental |

| IV | Evidence from well-designed case-control and cohort studies |

| V | Evidence from systematic reviews of descriptive and qualitative studies |

| VI | Evidence from a single descriptive or qualitative study |

| VII | Evidence from the opinion of authorities and/or reports of expert committees |

| First Author, Year, and Citation | PBM Dosimetry and Treatment Protocols | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ (nm) Light Source | Emission Mode | Power (mW) | Irradiance (W/cm2) | Energy (J)/ Point | Irradiation Points (Number and Location) | Fluence (J/cm2)/ Point | Beam Area (cm2) | Irradiation Time (s)/ Point | Frequency per Week/Rx Duration | Follow-Up | Photon Energy (eV) | Photon Fluence (p.J/cm2) | Einstein (ɇ) | |

| Hanna et al. 2022 [11] | 810 (laser) | CW | 200 | 1.97 | 6 | 9–Tongue (tip, dorsum, ventral) and along V3 and lingual nerves (Spot technique) | 6 (Total 59.1) | 0.088 | 30 | 2× a week/5 consecutive weeks | Up to 9 months | 1.5 | 88.656 | 19.7 |

| de Pedro et al. 2020 [40] | 810 (laser) | CW | 600 | 1.2 | 6 | 56–Lip, tongue, vestibular and buccal mucosa, hard palate (spot technique) | 12 | 0.5 | 10 | 2× a week/5 consecutive weeks | >4 months | 1.5 | 18 | 4 |

| Bardellini et al. 2019 [41] | 660, 800, 970 (laser) | Pulsed/ 50% duty cycle, 1–20,000 Hz | 3200 | 3.2 | 4.93 | Continuous sweeping movement over 150 cm2 treatment areas: tongue (lateral, dorsum, tip), lips, buccal mucosa | 4.93 | 150 (1 cm2 continuous sweeping motion) | Total 231 | 1× a week/ 10 weeks Rx | >1 month | 1.9 1.3 | 1404.5 960.9 2365.4 | 525.6 |

| Sugaya et al. 2016 [42] | 790 (laser) | CW | 120 | 4 | 1 | Tongue, palate, lips, buccal mucosa in centimetric grid pattern | 6 | 0.03 | 50 | 2× a week/2 consecutive weeks | 7,14,30,60 and 90-day | 1.5 | 9 | 2 |

| Arduino et al. 2016 [43] | 980 (laser) | CW | 300 | 1 | 3 | Depending on the painful areas: lip, tongue, buccal mucosa, palate (spot technique) | 10 | 0.28 | 10 | 2× a week/ 5 weeks | 8–12 weeks | 1.3 | 13 | 2.9 |

| de Abreu et al. 2024 [57] | 660 (laser) | CW | 100 | 0.1 | 6 | The tongue, buccal mucosa, and hard palate are irradiated in centimetric grid pattern | 6 | 1 | 60 | 2× a week/ 5 weeks | 12 months | 1.9 | 11.4 | 2.5 |

| PBM Dosimetry and Treatment Protocols | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ (nm) Laser | Emission Mode | Power (mW) | Irradiance (W/cm2) | Energy (J) | No. of Irradiation Points/Areas | Irradiation Location | Irradiation Technique | Fluence (J/cm2)/ Point | Beam Area (cm2) | Irradiation Time (s) | Frequency per Week/ Rx Duration | Laser- Tissue Distance | Photon Energy (eV) | Photon Fluence (p.J/cm2) | Einstein (ɇ) |

| 660, 790–980 (Single or * Multiwavelength, red and NIR) | CW/ * Pulsed | 100–600 | 0.1–4 (* higher irradiances potentially thermal) | 1–6/ point | 9–52 points | Intra and extra-oral of the affected areas, including V2 and V3 | Spot | 0.03–1 | 10–60/ point | 2× a week/5 consecutive weeks (Adjust to patient’s response) | <1 mm in contact | 1.3–1.9 | 6.5–22.8 | 1.4–5.1 | |

| 5–12 | |||||||||||||||

| * 3200 (* Average) | * 739 J per area ÷ 150 cm2 = 4.93 J/cm2 | 1 × 150 cm2 (Sum of all the treated areas) | * Continuous sweeping motion (CSM) | 150 (beam area 1 cm2 in CSM) | * Total 231 | * 1.5 cm | 1.3 and 1.9 | 6.409 9.367 15.78 | 3.5 | ||||||

| First Author, Year, and Citation | PBM Dosimetry and Treatment Protocols | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ (nm) Laser | Emission Mode | Power (mW) | Irradiance (W/cm2) | Energy (J)/Point | Irradiation Points (Number and Location) | Fluence (J/cm2) | Spot Size (cm2) | Irradiation Time (s) | No. Sessions/ Rx Duration | Follow-Up | Photon Energy (eV) | Photon Fluence (p.J/cm2) | Einstein (ɇ) | |

| Ebrahimi et al. 2018 [67] | 810 | CW | 200 | ~0.2544 | 5 | 2–3 cutaneous sites along the pain pathway of affected branches of V | 6.36 | ~0.79 | 25 | 3× a week/ 3 weeks (total 9 sessions) | 1 month | 1.5 | 7.5 | 1.6 |

| Eckerdal et al. 1996 [69] | 832 | CW | 31 | ~0.143 | 2 | 1–5 facial painful area along the affected branches of V | 9.2 | 0.22 | 64.5 | 1× a week/ 5 weeks | 12 months | 1.5 | 4.8 | 1.1 |

| Walker et al. 1987 [70] | 632.5 | Pulsed, 20 Hz, 50% duty cycle | 0.477 (Average) | 0.0476 | 0.0143 | Along V1–V3 (cutaneous) | ~0.36 | 0.04 at skin | 30—week 1 | 3× a week/ 10 weeks (Total 30 sessions) | Pain intensity assessed during Rx duration | 1.9 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| 0.0215 | ~0.54 | 45—week 2 | 1.0 | 0.2 | ||||||||||

| 0.0286 | ~0.72 | 60—week 3–6 | 1.4 | 0.3 | ||||||||||

| 0.0429 | ~1.07 | 90—week 7–10 | 0.7 | 0.1 | ||||||||||

| 3.76 | 0.84 | |||||||||||||

| PBM Dosimetry and Treatment Protocols | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ (nm) Laser | Emission Mode | Power (mW) | Irradiance (W/cm2) | Energy (J)/Point | Irradiation Points (Number and Location) | Fluence J/cm2 | Spot Size (cm2) | Irradiation Time (s)/ Point | Frequency per Week/ Rx Duration | Laser– Tissue Distance | Photon Energy (eV) | Photon Fluence (p.J/cm2) | Einstein (ɇ) |

| 810–832 (Single wavelength) | CW | 31–200 | ~0.15–0.25 | ~2–5 | 6 cutaneous points along the affected V1-V3 branches (2 points per branch). V2 and V3 are the most commonly affected nerves, and involvement is usually unilateral | ~6.3–9 | ~0.04–0.79 | 25–90 | 1–3× a week/ 3–5 weeks, (Up to 10 weeks, depending on the patient’s response. | At skin, with applied of pressure | 1.5 | 9.4–13.5 | 2.1–3 |

| 632.5 | Pulsed, 20 Hz, 50% duty cycle | 0.477 (Average) | 0.0476 | 0.014–0.043 (Stepwise increase) | ~0.36⟶1.07 (Progressive) | 1.9 | 0.68–2.0 | 0.1–0.4 | |||||

| First Author, Year and Citation | PBM Dosimetry and Treatment Protocols | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ (nm) | Emission Mode | Power (mW) | Irradiance (W/cm2) | Energy (J)/Point | Irradiation Points | Fluence (J/cm2) | Spot Size (cm2) | Irradiation Time (s)/ Point | No. Sessions/ Rx Duration | Follow-Up | Photon Energy (eV) | Photon Fluence (p.J/cm2) | Einstein (ɇ) | |

| Toshikazu et al. 1997 [74] | 830 | CW | 60 (MLD-1002) | 0.48 | 10.8 | Single point—stellate ganglion (C7/T1) with applied pressure. Spot treatment technique | 0.126 (4 mm) | 180 | 2× a week (1× for 60 mW and 1× for 150 mW) -then crossover | Only 30 min post-Rx | 1.5 | 2063.7 5159.2 | 458.6 1146.5 | |

| 150 (MLD-1003) | 1.19 | 27 | 214.8 | 180 | ||||||||||

| Kemmostsu et al. 1991 [77] | 830 | CW | 60 (MLD-2001) | ~1.2–3 | ~0.6 | V dermatome, tender, painful points (superficial points). Spot treatment technique ~7–12 points per clinical and reported parameters | 30 | 0.02(0.6 W ÷ 3 W/cm2) | 10 | 2–3× a week at out-patients; 4–6× a week at in-patients/ 36 on average | Refers to average Rx duration 36 ± 12 (no post-Rx) | 1.5 | 5159.2 10,318.5 | 1146.5 2292.9 |

| Moore et al. 1988 [81] | 830 | CW | 60 | 3 | 0.9 | V dermatome (spot treatment technique). ~10 points per clinical and reported parameters. | 45 | 0.02 | 15 | 2× a week/ 8 treatments in total | 1 month | 1.5 | 2160 | 480 |

| PBM Dosimetry and Treatment Protocols | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

λ (nm)

Laser | Emission Mode |

Power (mW) |

Irradiance (W/cm2) | Energy (J)/Point |

Irradiation Points

(Number and Location) |

Fluence (J/cm2) | Spot Size (cm2) | Irradiation Time (s)/Point |

Frequency

per Week/ Rx Duration |

Laser-

Tissue Distance | Photon Energy (eV) |

Photon

Fluence (p.J/cm2) | Einstein ( ɇ ) |

| 830 | CW | 60–150 | 0.48–3 | ~0.6–27 depending on irradiation time | 7–12 points along V1-V3: Any combination of V1, V2, and V3 depends on where the shingles outbreak occurred: forehead: 2–3; around eye: 2–3; upper eyelid: 1–2; bridge of nose: 1–2; optional temple or lateral forehead: 1–2. 60 mW is effective for superficial points. One point to the stellate ganglion (C7/T1), whereby 150 mW is more effective than 60 mW | 30–45 to the V branches (superficial); 85.9–214.8 to the stellate ganglion block | 0.02–0.1257 | 10–15 to each point of V1-V3 branches; 180 for 1 point to the stellate ganglion block. Spot treatment technique | 2–4× per week up to 36 sessions, adjusted per patient’s response | At skin (cutaneous contact) with applied pressure for deep-seated tissues | 1.5 | 173.85 –389.7 | 38.63–86.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hanna, R.; Chow, R.; Dalvi, S.; Arany, P.R.; Bensadoun, R.-J.; Santos-Silva, A.R.; Tunér, J.; Carroll, J.D.; Hamblin, M.R.; Anders, J.; et al. Photobiomodulation Therapy in the Management of Orofacial Neuropathic Pain—WALT Position Paper 2026. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031304

Hanna R, Chow R, Dalvi S, Arany PR, Bensadoun R-J, Santos-Silva AR, Tunér J, Carroll JD, Hamblin MR, Anders J, et al. Photobiomodulation Therapy in the Management of Orofacial Neuropathic Pain—WALT Position Paper 2026. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031304

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanna, Reem, Roberta Chow, Snehal Dalvi, Praveen R Arany, René-Jean Bensadoun, Alan Roger Santos-Silva, Jan Tunér, James D Carroll, Michael R Hamblin, Juanita Anders, and et al. 2026. "Photobiomodulation Therapy in the Management of Orofacial Neuropathic Pain—WALT Position Paper 2026" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031304

APA StyleHanna, R., Chow, R., Dalvi, S., Arany, P. R., Bensadoun, R.-J., Santos-Silva, A. R., Tunér, J., Carroll, J. D., Hamblin, M. R., Anders, J., Rochkind, S., Heiskanen, V., Raber-Durlacher, J. E., & Laakso, E.-L. (2026). Photobiomodulation Therapy in the Management of Orofacial Neuropathic Pain—WALT Position Paper 2026. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031304