Association Between MGMT Promoter Methylation and Clinical and Lifestyle Factors in Glioblastoma: A Single-Center Study in Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Histopathological and MGMT Methylation Review

2.2. Definition of Clinical and Lifestyle Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated with MGMT Promoter Methylation

| Variable | MGMT (+) (n = 48) | MGMT (−) (n = 57) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean) | 41–84 (64.7) | 47–87 (65.2) | 0.8 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.6 | ||

| Male | 28 (58.3) | 29 (50.9) | |

| Female | 20 (41.7) | 28 (49.1) | |

| Body mass index (BMI) , kg/m2 (median) | 18.8–31.3 (23.6) | 18.8–31.2 (23.6) | 0.8 |

| Weight category, n (%) | 0.3 | ||

| Normal weight | 35 (72.9) | 36 (63.2) | |

| Overweight/Obese | 13 (27.1) | 21 (36.8) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.04 | ||

| Never or former smoker | 37 (77.1) | 53 (93.0) | |

| Current smoker | 11 (22.9) | 4 (7.0) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.3 | ||

| Yes | 19 (39.6) | 17 (29.8) | |

| No | 29 (60.4) | 40 (70.2) | |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 0.5 | ||

| Yes | 4 (8.3) | 8 (14.0) | |

| No | 44 (91.7) | 49 (86.0) | |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 0.6 | ||

| Yes | 5 (10.4) | 9 (15.8) | |

| No | 43 (89.6) | 48 (84.2) |

3.3. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with MGMT Promoter Methylation

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per year) | 1 | 0.93–1.03 | 0.4 |

| Female sex | 1.1 | 0.43–2.62 | 0.9 |

| Overweight or obese | 0.6 | 0.23–1.49 | 0.3 |

| Current smoker | 4.6 | 1.21–20.13 | 0.03 |

| Hypertension | 3.6 | 1.15–11.95 | 0.03 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 0.3 | 0.05–1.42 | 0.1 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.5 | 0.12–1.92 | 0.3 |

3.4. Association Between Smoking Exposure and MGMT Promoter Methylation

| <20 Pack-Years (n = 8) | ≥20 Pack-Years (n = 25) | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGMT (+), n (%) | 2 (25.0) | 17 (68.0) | 6.0 | 0.83–73.47 | 0.047 |

| MGMT (–), n (%) | 6 (75.0) | 8 (32.0) |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wen, P.Y.; Kesari, S. Malignant Gliomas in Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 492–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Dey, D.; Barik, D.; Mohapatra, I.; Kim, S.; Sharma, M.; Prasad, S.; Wang, P.; Singh, A.; Singh, G. Glioblastoma at the Crossroads: Current Understanding and Future Therapeutic Horizons. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, D.; Raposa, B.L.; Freihat, O.; Simon, M.; Mekis, N.; Cornacchione, P.; Kovács, Á. Glioblastoma: Clinical Presentation, Multidisciplinary Management, and Long-Term Outcomes. Cancers 2025, 17, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegi, M.E.; Diserens, A.-C.; Gorlia, T.; Hamou, M.-F.; de Tribolet, N.; Weller, M.; Kros, J.M.; Hainfellner, J.A.; Mason, W.; Mariani, L.; et al. MGMT Gene Silencing and Benefit from Temozolomide in Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riganti, C.; Salaroglio, I.C.; Pinzòn-Daza, M.L.; Caldera, V.; Campia, I.; Kopecka, J.; Mellai, M.; Annovazzi, L.; Couraud, P.-O.; Bosia, A.; et al. Temozolomide Down-Regulates P-Glycoprotein in Human Blood–Brain Barrier Cells by Disrupting Wnt3 Signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.; Tanaka, M.; Trepel, J.; Reinhold, W.C.; Rajapakse, V.N.; Pommier, Y. Temozolomide in the Era of Precision Medicine. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barciszewska, A.-M.; Gurda, D.; Głodowicz, P.; Nowak, S.; Naskręt-Barciszewska, M.Z. A New Epigenetic Mechanism of Temozolomide Action in Glioma Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, M.; Van Den Bent, M.; Preusser, M.; Le Rhun, E.; Tonn, J.C.; Minniti, G.; Bendszus, M.; Balana, C.; Chinot, O.; Dirven, L.; et al. EANO Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diffuse Gliomas of Adulthood. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.S.; Kramp, T.R.; Palanichamy, K.; Tofilon, P.J.; Camphausen, K. MGMT Inhibition Regulates Radioresponse in GBM, GSC, and Melanoma. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganau, M.; Foroni, R.I.; Gerosa, M.; Zivelonghi, E.; Longhi, M.; Nicolato, A. Radiosurgical Options in Neuro-Oncology: A Review on Current Tenets and Future Opportunities. Part I: Therapeutic Strategies. Tumori J. 2014, 100, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganau, M.; Foroni, R.I.; Gerosa, M.; Ricciardi, G.K.; Longhi, M.; Nicolato, A. Radiosurgical Options in Neuro-Oncology: A Review on Current Tenets and Future Opportunities. Part II: Adjuvant Radiobiological Tools. Tumori J. 2015, 101, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szylberg, M.; Sokal, P.; Śledzińska, P.; Bebyn, M.; Krajewski, S.; Szylberg, Ł.; Szylberg, A.; Szylberg, T.; Krystkiewicz, K.; Birski, M.; et al. MGMT Promoter Methylation as a Prognostic Factor in Primary Glioblastoma: A Single-Institution Observational Study. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanc, J.L.; Wager, M.; Guilhot, J.; Kusy, S.; Bataille, B.; Chantereau, T.; Lapierre, F.; Larsen, C.J.; Karayan-Tapon, L. Correlation of Clinical Features and Methylation Status of MGMT Gene Promoter in Glioblastomas. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2004, 68, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Hong, Y.; Kim, S.-Y.; London, S.J.; Kim, W.J. DNA Methylation and Smoking in Korean Adults: Epigenome-Wide Association Study. Clin. Epigenetics 2016, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucoreanu, C.; Tigu, A.-B.; Nistor, M.; Moldovan, R.-C.; Pralea, I.-E.; Iacobescu, M.; Iuga, C.-A.; Szabo, R.; Dindelegan, G.-C.; Ciuce, C. Epigenetic and Molecular Alterations in Obesity: Linking CRP and DNA Methylation to Systemic Inflammation. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 7430–7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez, R.; Chapela, S.P.; Álvarez-Córdova, L.; Bautista-Valarezo, E.; Sarmiento-Andrade, Y.; Verde, L.; Frias-Toral, E.; Sarno, G. Epigenetics in Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus: New Insights. Nutrients 2023, 15, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Mao, C.; Liu, S.; Tao, Y.; Xiao, D. Epigenetic Modifications in Obesity-associated Diseases. MedComm 2024, 5, e496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopyan, G.; Bonavida, B. Understanding Tobacco Smoke Carcinogen NNK and Lung Tumorigenesis (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2006, 29, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M. Epigenetic Mechanisms and Hypertension. Hypertension 2018, 72, 1244–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.A.; Huan, T.; Ligthart, S.; Gondalia, R.; Jhun, M.A.; Brody, J.A.; Irvin, M.R.; Marioni, R.; Shen, J.; Tsai, P.-C.; et al. DNA Methylation Analysis Identifies Loci for Blood Pressure Regulation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 888–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A Summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Sahm, F. A Narrative Review of What the Neuropathologist Needs to Tell the Clinician in Neuro-Oncology Practice Concerning WHO CNS5. Glioma 2022, 5, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate Body-Mass Index for Asian Populations and Its Implications for Policy and Intervention Strategies. Lancet 2004, 363, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lan, Q.; Siegfried, J.M.; Luketich, J.D.; Keohavong, P. Aberrant Promoter Methylation of P16 and MGMT Genes in Lung Tumors from Smoking and Never-Smoking Lung Cancer Patients. Neoplasia 2006, 8, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmann, M.; Kaina, B. O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase (MGMT): Impact on Cancer Risk in Response to Tobacco Smoke. Mutat. Res. —Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2012, 736, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, S.; Mafune, A.; Kohda, N.; Hama, T.; Urashima, M. Associations among Smoking, MGMT Hypermethylation, TP53-Mutations, and Relapse in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, T.; Rasmussen, M.; Heitmann, B.; Tønnesen, H. Gold Standard Program for Heavy Smokers in a Real-Life Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4186–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Han, K.-D.; Park, Y.-M.; Bae, J.M.; Kim, S.U.; Jeun, S.-S.; Yang, S.H. Cigarette Smoking Is Associated with Increased Risk of Malignant Gliomas: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Cancers 2020, 12, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joehanes, R.; Just, A.C.; Marioni, R.E.; Pilling, L.C.; Reynolds, L.M.; Mandaviya, P.R.; Guan, W.; Xu, T.; Elks, C.E.; Aslibekyan, S.; et al. Epigenetic Signatures of Cigarette Smoking. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2016, 9, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Chen, X.; Hong, Q.; Deng, Z.; Ma, H.; Xin, Y.; Fang, Y.; Ye, H.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C.; et al. Meta-Analyses of Gene Methylation and Smoking Behavior in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.-K.; Hsieh, Y.-S.; Lin, P.; Hsu, H.-S.; Chen, C.-Y.; Tang, Y.-A.; Lee, C.-F.; Wang, Y.-C. The Tobacco-Specific Carcinogen NNK Induces DNA Methyltransferase 1 Accumulation and Tumor Suppressor Gene Hypermethylation in Mice and Lung Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.; Sharma, S.K.; Sekhon, G.S.; Saikia, B.J.; Mahanta, J.; Phukan, R.K. Promoter Methylation of MGMT Gene in Serum of Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in North East India. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 9955–9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povey, A.C.; O’Donnell, P.; Barber, P.; Watson, M.; Margison, G.P.; Koref, M.F.S. Smoking Is Associated with a Decrease of O6 -alkylguanine-DNA Alkyltransferase Activity in Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.; Zhang, G.; Ye, S.; Tian, S.; Li, H.; Zuo, F.; Wan, J.; Cai, H. Regulatory Mechanisms of O6-Methylguanine Methyltransferase Expression in Glioma Cells. Sci. Prog. 2025, 108, 00368504251345014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawachi, T.; Soejima, H.; Urano, T.; Zhao, W.; Higashimoto, K.; Satoh, Y.; Matsukura, S.; Kudo, S.; Kitajima, Y.; Harada, H.; et al. Silencing Effect of CpG Island Hypermethylation and Histone Modifications on O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase (MGMT) Gene Expression in Human Cancer. Oncogene 2003, 22, 8835–8844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreth, S.; Limbeck, E.; Hinske, L.C.; Schütz, S.V.; Thon, N.; Hoefig, K.; Egensperger, R.; Kreth, F.W. In Human Glioblastomas Transcript Elongation by Alternative Polyadenylation and miRNA Targeting Is a Potent Mechanism of MGMT Silencing. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 125, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.; Fabbri, E.; Santangelo, A.; Bezzerri, V.; Cantù, C.; Gennaro, G.D.; Finotti, A.; Ghimenton, C.; Eccher, A.; Dechecchi, M.; et al. miRNA Array Screening Reveals Cooperative MGMT-Regulation between miR-181d-5p and miR-409-3p in Glioblastoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 28195–28206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Begum, R.; Thota, S.; Batra, S. A Systematic Review of Smoking-Related Epigenetic Alterations. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 2715–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, I.; Charchar, F. Epigenetic Modifications in Essential Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Xu, L.; Peng, F.; Zhao, N.; Fu, B.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Association between MGMT Hypermethylation and the Clinicopathological Characteristics of Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. The Change of MGMT Gene Expression in Glioma Patients Was Affected by Methylation Regulation and in the Treatment of Alkylation Agent. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2019, 12, 8725–8731. [Google Scholar]

- Malueka, R.G.; Hartanto, R.A.; Alethea, M.; Sianipar, C.M.; Wicaksono, A.S.; Basuki, E.; Dananjoyo, K.; Asmedi, A.; Dwianingsih, E.K. Associations among Smoking, IDH Mutations, MGMT Promoter Methylation, and Grading in Glioma: A Cross-Sectional Study. F1000Research 2022, 11, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIOS-Consortium; CARDIo GRAMplusCD; LifeLines Cohort Study; The InterAct Consortium; Kato, N.; Loh, M.; Takeuchi, F.; Verweij, N.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; et al. Trans-Ancestry Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies 12 Genetic Loci Influencing Blood Pressure and Implicates a Role for DNA Methylation. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

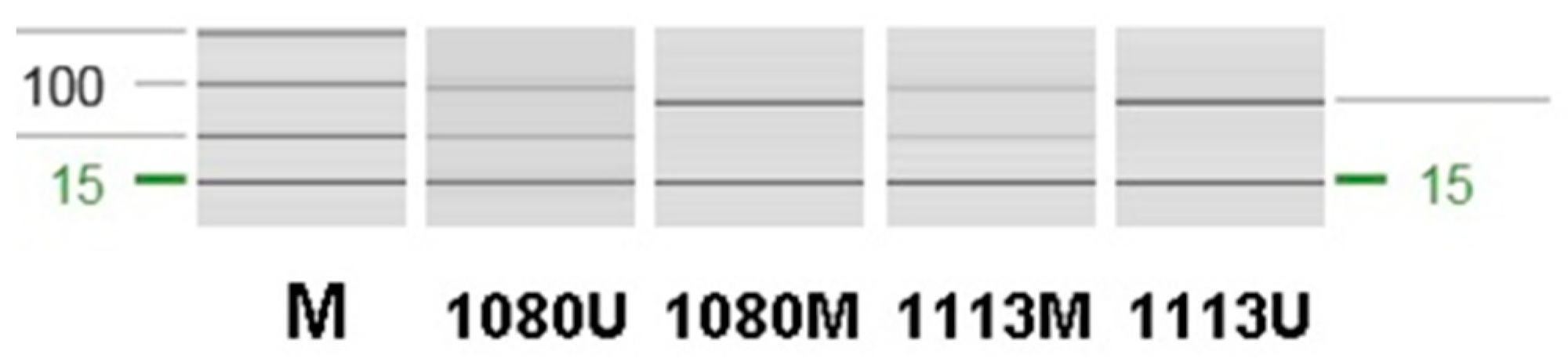

| Methylated pair | Forward | 5′-TTTCGACGTTCGTAGGTTTTCGC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GCACTCTTCCGAAAACGAAACG-3′ | |

| Unmethylated pair | Forward | 5′-TTTGTGTTTTGATGTTTGTAGGTTTTTGT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AACTCCACACTCTTCCAAAAACAAAAA-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, M.-S.; Lee, Y.-M.; Son, S.-A.; Kim, D.; Lee, C.; Hwang, J.-H. Association Between MGMT Promoter Methylation and Clinical and Lifestyle Factors in Glioblastoma: A Single-Center Study in Korea. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031305

Kim M-S, Lee Y-M, Son S-A, Kim D, Lee C, Hwang J-H. Association Between MGMT Promoter Methylation and Clinical and Lifestyle Factors in Glioblastoma: A Single-Center Study in Korea. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031305

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Mee-Seon, Yu-Mi Lee, Shin-Ah Son, DongJa Kim, Chaejin Lee, and Jeong-Hyun Hwang. 2026. "Association Between MGMT Promoter Methylation and Clinical and Lifestyle Factors in Glioblastoma: A Single-Center Study in Korea" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031305

APA StyleKim, M.-S., Lee, Y.-M., Son, S.-A., Kim, D., Lee, C., & Hwang, J.-H. (2026). Association Between MGMT Promoter Methylation and Clinical and Lifestyle Factors in Glioblastoma: A Single-Center Study in Korea. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031305