Likelihood of Blood Culture Positivity Using SeptiCyte RAPID

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohorts

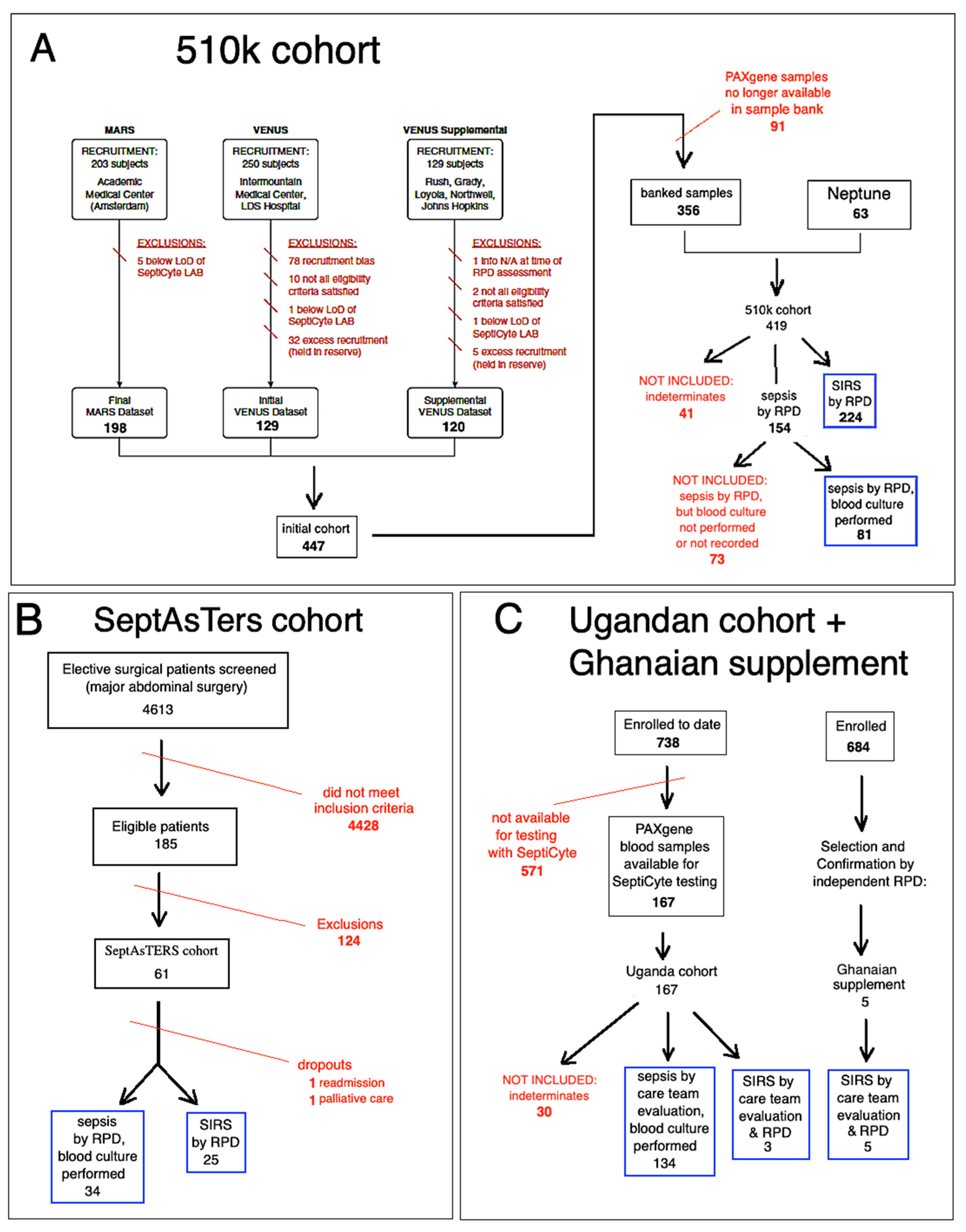

2.1.1. The “510k” Study

2.1.2. The “SeptAsTERS” Study

2.1.3. The “UGANDA” Study

2.1.4. The Ghanaian Supplement

2.2. SeptiCyte RAPID

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Conventional Statistical Tests

2.3.2. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis

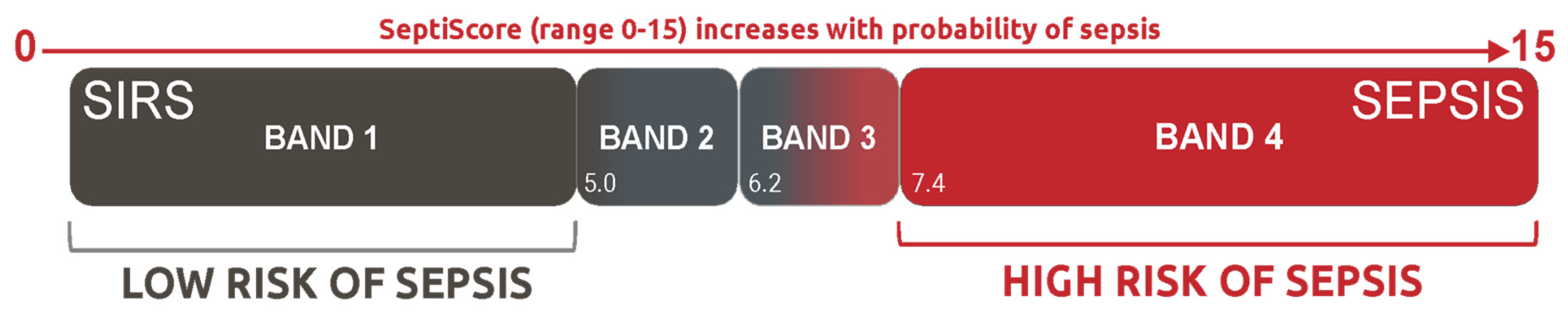

2.3.3. SeptiScore Binary Cutoffs

2.3.4. Probability Ratio Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographic, Clinical, and Laboratory Characteristics

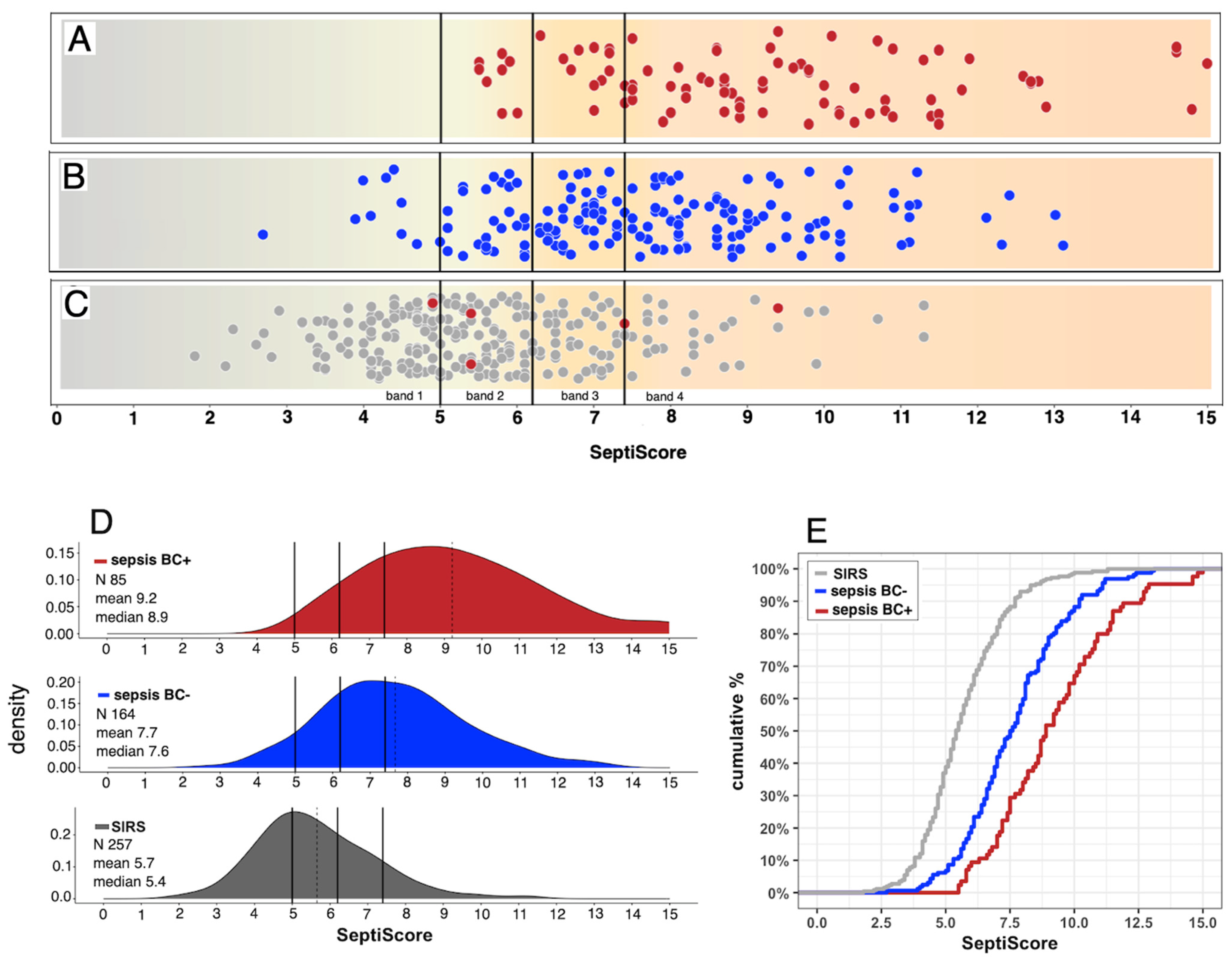

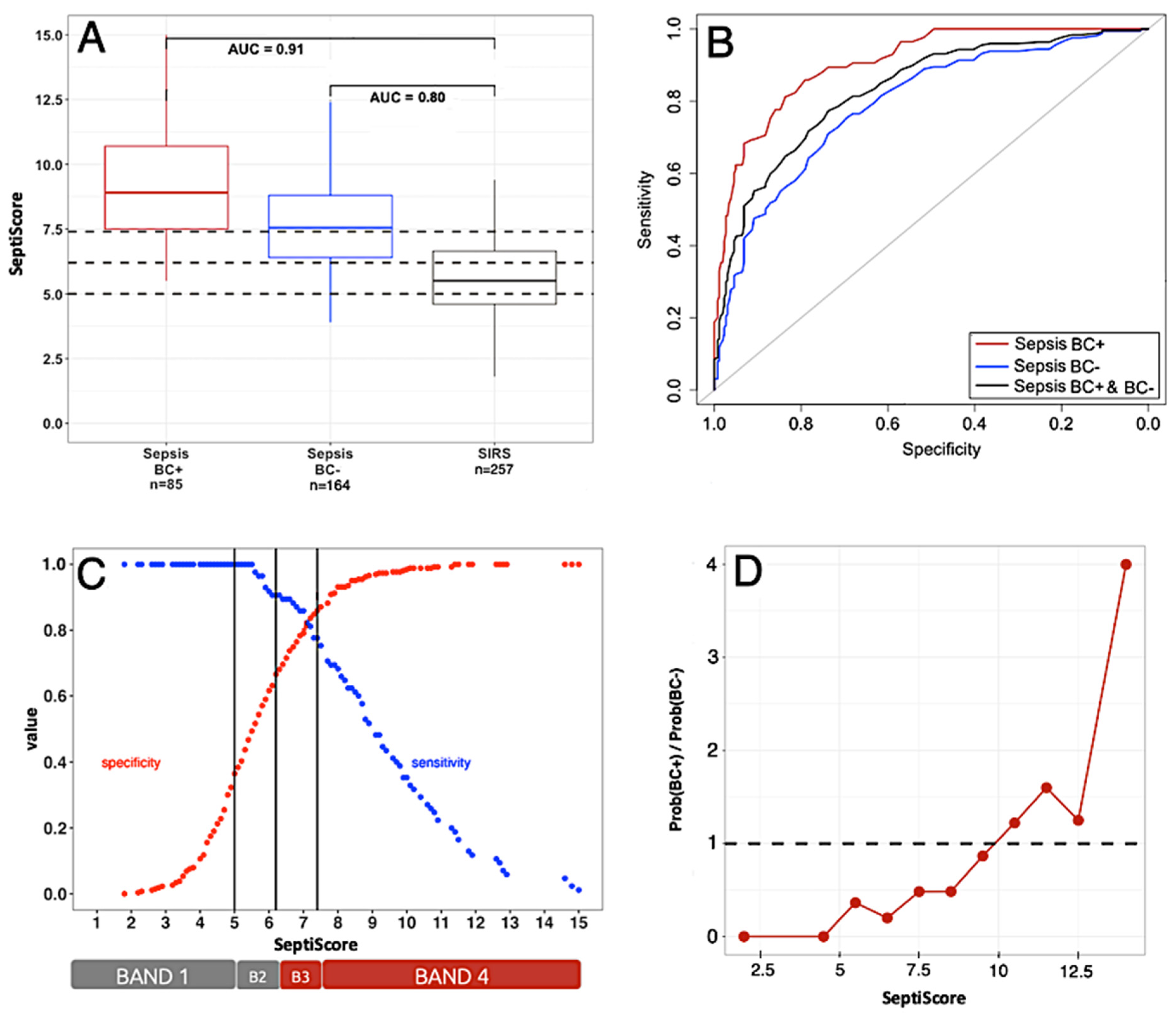

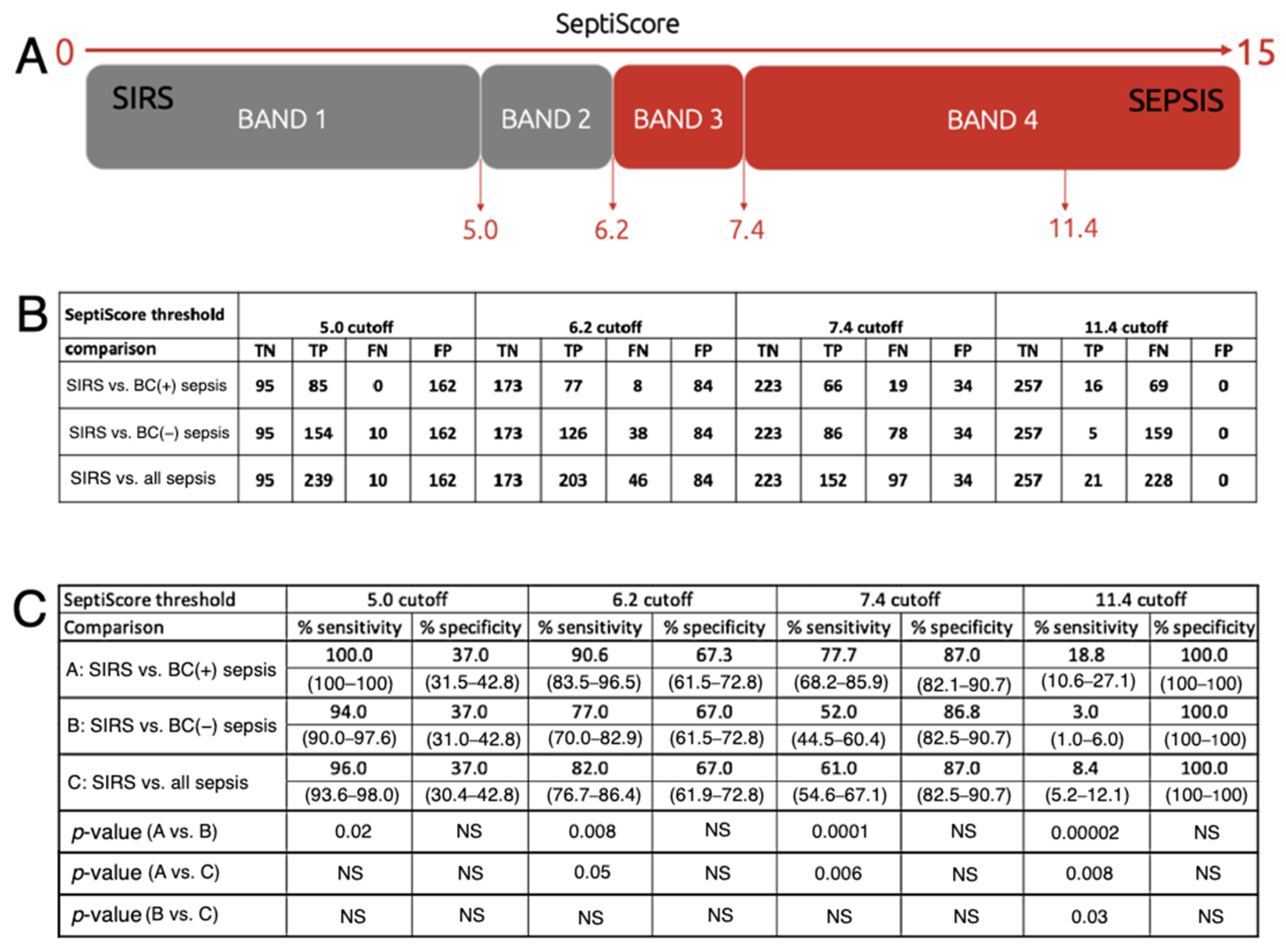

3.2. Performance of SeptiCyte RAPID Compared to Blood Culture

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AUC | area under [ROC] curve |

| BC | blood culture(s) |

| BSI | bloodstream infection |

| CI | confidence interval |

| Cq | threshold-crossing cycle (in qPCR) |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| ED | Emergency department |

| FN | False Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| F | female |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration (USA) |

| FUBC | follow-up blood culture |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| LMIC | Lower and middle income country |

| LR+ | positive likelihood ratio |

| M | male |

| mL | milliliter |

| ND | not determined |

| NS | not significant |

| PLA2G7 | Phospholipase A2 group VII (mRNA transcript) |

| PLAC8 | Placenta-associated 8 (mRNA transcript) |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic (curve) |

| RPD | Retrospective Physician Diagnosis |

| RT-qPCR | reverse transcription—quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SIRS | systemic inflammatory response syndrome |

| SOFA | sequential organ failure assessment (score) |

| TN | True Negative |

| TP | True Positive |

| WBC | white blood cell |

References

- Ziegler, M.J.; Pellegrini, D.C.; Safdar, N. Attributable mortality of central line associated bloodstream infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection 2015, 43, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reunes, S.; Rombaut, V.; Vogelaers, D.; Brusselaers, N.; Lizy, C.; Cankurtaran, M.; Labeau, S.; Petrovic, M.; Blot, S. Risk factors and mortality for nosocomial bloodstream infections in elderly patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 22, e39–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.G.; Simos, P.; Sivabalan, P.; Escolà-Vergé, L.; Garnham, K.; Isler, B.; on behalf of the ESGBIES Study Group. An Update on Recent Clinical Trial Data in Bloodstream Infection. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, J.U.; Theodosis, C.; Jacob, S.T.; Wira, C.R.; Groce, N.E. Surviving Sepsis in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: New Directions for Care and Research. Lancet Inf. Dis. 2009, 9, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Le, Y. Challenges in the Management of Sepsis in a Resource-Poor Setting. Int. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 8, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tian, Y.; Liu, J.; Ran, J.; Sun, S.; Zhao, S.; Ge, Y.; Martinez, L.; Chen, X.; Cao, P. COVID-19 and sepsis-related excess mortality in the US during the first three years: A national-wide time series study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2024, 194, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shappell, C.N.; Klompas, M.; Chan, C.; Chen, T.; Kanjilal, S.; McKenna, C.; Rhee, C.; CDC Prevention Epicenters Program. Use of Electronic Clinical Data to Track Incidence and Mortality for SARS-CoV-2–Associated Sepsis. JAMA Netw. Open. 2023, 6, e2335728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keven, K.; Ates, K.; Sever, M.S.; Yenicesu, M.; Canbakan, B.; Arinsoy, T.; Ozdemir, N.; Duranay, M.; Altun, B.; Erek, E. Infectious complications after mass disasters: The Marmara earthquake experience. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 35, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.Y.; Messenger, N. Infectious Diseases After Hydrologic Disasters. Emerg. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 36, 835–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallett, S.J.; Mistry, R.; Lambert, Z.L.; Woolley, S.D.; Abbara, A.; Breathnach, A.O.; Lamb, L.E.; Williams, A.; Mughal, N.; Moshynets, O.; et al. Conflict and catastrophe-related severe burn injuries: A challenging setting for antimicrobial decision-making. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carius, B.M.; Bebarta, G.E.; April, M.D.; Fisher, A.D.; Rizzo, J.; Ketter, P.; Wenke, J.C.; Salinas, J.; Bebarta, V.S.; Schauer, S.G. A Retrospective Analysis of Combat Injury Patterns and Prehospital Interventions Associated with the Development of Sepsis. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2023, 27, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahli, Z.T.; Bizri, A.R.; Abu-Sittah, G.S. Microbiology and risk factors associated with war-related wound infections in the Middle East. Epidemiol. Infect. 2016, 144, 2848–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, M.S.; Henderson, I.R.; Capon, R.J.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline as of December 2022. J. Antibiot. 2023, 76, 431–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opal, S.M.; Wittebole, X. Biomarkers of Infection and Sepsis. Crit. Care Clin. 2020, 36, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambregts, M.M.C.; Bernards, A.T.; Beek, M.T.; van der Visser, L.G.; de Boer, M.G. Time to positivity of blood cultures supports early re-evaluation of empiric broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0208819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, B.; Morris, A.M.; Tomlinson, G.; Detsky, A.S. Does This Adult Patient With Suspected Bacteremia Require Blood Cultures? JAMA 2012, 308, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, E.H.; Mann, S.; Hsu, T.-C.; Hsu, W.-T.; Liu, C.C.-Y.; Bhakta, T.; Hassani, D.M.; Lee, C.C. Incidence, trends, and outcomes of infection sites among hospitalizations of sepsis: A nationwide study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre, V.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Carroll, K.C.; Salinas, A.B.; Gadala, A.; Bower, C.; Boyd, S.; Degnan, K.O.; Dhaubhadel, P.; Diekema, D.J.; et al. Blood Culture Use in Medical and Surgical Intensive Care Units and Wards. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2454738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellhammar, L.; Kahn, F.; Whitlow, C.; Kander, T.; Christensson, B.; Linder, A. Bacteremic sepsis leads to higher mortality when adjusting for confounders with propensity score matching. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, C.; Skoglund, E.; Muldrew, K.L.; Garey, K.W. Economic health care costs of blood culture contamination: A systematic review. Am. J. Infec. Control 2019, 47, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, P.; Strzelecki, A.-C.; Dautezac, V.; Hennet, M.-A.; Borredon, G.; Brisou, P.; Girard, D.; Assi, A. Diagnostic uncertainties in patients with bacteraemia: Impact on antibiotic prescriptions and outcome. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 80, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donner, L.M.; Campbell, W.S.; Lyden, E.; Van Schooneveld, T.C. Assessment of Rapid-Blood-Culture-Identification Result Interpretation and Antibiotic Prescribing Practices. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balıkçı, A.; Belas, Z.; Eren Topkaya, A. Kan Kültürü Pozitifliği: Etken ya da Kontaminasyon mu? [Blood culture positivity: Is it pathogen or contaminant?]. Mikrobiyol. Bul. 2013, 47, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, B.; Islam, M.S.; Rahman, A.; Marzan, M.; Rafiqullah, I.; Connor, N.E.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Islam, M.; Hamer, D.H.; Hibberd, P.L.; et al. Understanding Bacterial Isolates in Blood Culture and Approaches Used to Define Bacteria as Contaminants: A Literature Review. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2016, 35, S45–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, B.; Dargère, S.; Arendrup, M.C.; Parienti, J.J.; Tattevin, P. How to Optimize the Use of Blood Cultures for the Diagnosis of Bloodstream Infections? A State-of-the Art. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, E.J.; Miller, J.M.; Weinstein, M.P.; Richter, S.S.; Gilligan, P.H.; Thomson, R.B., Jr.; Bourbeau, P.; Carroll, K.C.; Kehl, S.C.; Dunne, W.M.; et al. A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2013 recommendations by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, e22–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre, V.; Sharara, S.L.; Salinas, A.B.; Carroll, K.C.; Desai, S.; Cosgrove, S.E. Does This Patient Need Blood Cultures? A Scoping Review of Indications for Blood Cultures in Adult Nonneutropenic Inpatients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, S.; Bourbeau, P.; Swartz, B.; Brecher, S.; Carroll, K.C.; Stamper, P.D.; Dunne, W.M.; McCardle, T.; Walk, N.; Fiebelkorn, K.; et al. Timing of specimen collection for blood cultures from febrile patients with bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 1381–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balk, R.; Esper, A.M.; Martin, G.S.; Miller, R.R., III; Lopansri, B.K.; Burke, J.P.; Levy, M.; Opal, S.; Rothman, R.E.; D’Alessio, F.R.; et al. Validation of SeptiCyte RAPID to Discriminate Sepsis from Non-Infectious Systemic Inflammation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balk, R.; Esper, A.M.; Martin, G.S.; Miller, R.R., III; Lopansri, B.K.; Burke, J.P.; Levy, M.; Rothman, R.E.; D’Alessio, F.R.; Sidhaye, V.K.; et al. Rapid and Robust Identification of Sepsis Using SeptiCyte RAPID in a Heterogeneous Patient Population. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, L.; Seldon, T.A.; Brandon, R.A.; Kirk, J.T.; Rapisarda, A.; Sutherland, A.J.; Presneill, J.J.; Venter, D.J.; Lipman, J.; Thomas, M.R.; et al. A Molecular Host Response Assay to Discriminate Between Sepsis and Infection-Negative Systemic Inflammation in Critically Ill Patients: Discovery and Validation in Independent Cohorts. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, M.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Ju, S.; Zhou, J.; et al. Multifaced roles of PLAC8 in cancer. Biomark. Res. 2021, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candels, L.S.; Becker, S.; Trautwein, C. PLA2G7: A new player in shaping energy metabolism and lifespan. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2022, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Fu, J.N.; Chen, G.B.; Zhang, X. Plac8-ERK pathway modulation of monocyte function in sepsis. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Jiang, M.; Qian, J.; Ge, Z.; Xu, F.; Liao, W. The role of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 in inflammatory response and macrophage infiltration in sepsis and the regulatory mechanisms. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2024, 24, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.R., 3rd; Lopansri, B.K.; Burke, J.P.; Levy, M.; Opal, S.; Rothman, R.E.; D’Alessio, F.R.; Sidhaye, V.K.; Aggarwal, N.R.; Balk, R.; et al. Validation of a Host Response Assay, SeptiCyte LAB, for Discriminating Sepsis from Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome in the ICU. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care. 2018, 198, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Forst, M.; Back, L.; Tourelle, K.M.; Gruneberg, D.; Weigand, M.A.; Schmitt, F.C.F.; Dietrich, M. SeptAsTERS- SeptiCyte RAPID as assessment tool for early recognition of sepsis—A prospective observational study. Infection 2024, 53, 953–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, P.W.; Okello, S.; Wailagala, A.; Ayebare, R.R.; Olebo, D.F.; Kayiira, M.; Kemigisha, S.M.; Kayondo, W.; Gregory, M.; Koehler, J.W.; et al. Long-term Mortality Among Hospitalized Adults with Sepsis in Uganda: A Prospective Cohort Study. medRxiv 2023, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.M.; Fink, M.P.; Marshall, J.C.; Abraham, E.; Angus, D.; Cook, D.; Cohen, J.; Opal, S.M.; Vincent, J.L.; Ramsay, G.; et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 31, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Klouwenberg, P.M.; Ong, D.S.; Bos, L.D.; de Beer, F.M.; van Hooijdonk, R.T.; Huson, M.A.; Straat, M.; van Vught, L.A.; Wieske, L.; Horn, J.; et al. Interobserver agreement of centers for disease control and prevention criteria for classifying infections in critically ill patients. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 41, 2373–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Klouwenberg, P.M.; van Mourik, M.S.; Ong, D.S.; Horn, J.; Schultz, M.J.; Cremer, O.L.; Bonten, M.J.; MARS Consortium. Electronic implementation of a novel surveillance paradigm for ventilator-associated events. Feasibility and validation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar-Hari, M.; Phillips, G.S.; Levy, M.L.; Seymour, C.W.; Liu, V.X.; Deutschman, C.S.; Angus, D.C.; Rubenfeld, G.D.; Singer, M.; Sepsis Definitions Task Force. Developing a New Definition and Assessing New Clinical Criteria for Septic Shock: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, P.W.; Mehta, R.; Oppong, C.K.; Tin, S.; Ko, E.; Tsalik, E.L.; Chenoweth, J.; Rozo, M.; Adams, N.; Beckett, C.; et al. Screening tools for predicting mortality of adults with suspected sepsis: An international sepsis cohort validation study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenoweth, J.G.; Colantuoni, C.; Striegel, D.A.; Genzor, P.; Brandsma, J.; Blair, P.W.; Krishnan, S.; Chiyka, E.; Fazli, M.; Mehta, R.; et al. Gene expression signatures in blood from a West African sepsis cohort define host response phenotypes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; ISBN 3-900051-07-0. Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Rizopoulos, D. ltm: An R package for Latent Variable Modeling and Item Response Theory Analyses. J. Stat. Softw. 2006, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, J.A.; McNeil, B.J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982, 143, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, X.; Turck, N.; Hainard, A.; Tiberti, N.; Lisacek, F.; Sanchez, J.-C.; Müller, M. pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delong, E.R.; Delong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the Areas under Two or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves: A Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkahwagy, D.M.A.S.; Kiriacos, C.J.; Mansour, M. Logistic regression and other statistical tools in diagnostic biomarker studies. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 2172–2180, Erratum in Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.; Bithell, J. Bootstrap confidence intervals: When, which, what? A practical guide for medical statisticians. Stat Med. 2000, 19, 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Rasheed, A.; Siddiqui, A.A.; Naseer, M.; Wasim, S.; Akhtar, W. Non-Parametric Test for Ordered Medians: The Jonckheere Terpstra Test. Int. J. Stats. Med. Res. 2015, 4, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinkel, M.; Boerman, A.; Carroll, K.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Hsu, Y.J.; Klein, E.; Nanayakkara, P.; Schade, R.; Wiersinga, W.J.; Fabre, V. Impact of blood culture contamination on antibiotic use, resource utilization, and clinical outcomes: A retrospective cohort study in Dutch and US hospitals. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 11, ofad644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doern, G.V.; Carroll, K.C.; Diekema, D.J.; Garey, K.W.; Rupp, M.E.; Weinstein, M.P.; Sexton, D.J. Practical guidance for clinical microbiology laboratories: A comprehensive update on the problem of blood culture contamination and a discussion of methods for addressing the problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 33, e00009-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI. Principles and Procedures for Blood Cultures, 2nd ed.; CLSI guideline M47; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Phua, J.; Ngerng, W.; See, K.; Tay, C.; Kiong, T.; Lim, H.; Chew, M.; Yip, H.; Tan, A.; Khalizah, H.; et al. Characteristics and outcomes of culture-negative versus culture-positive severe sepsis. Crit. Care 2013, 17, R202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, J.; Kollef, M.H. Culture-negative sepsis. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2020, 26, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Yang, H.; Li, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, D. Comparison of culture-negative and culture-positive sepsis or septic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Oh, J.H.; Oh, D.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Hyun, D.G.; Park, M.H.; Lim, C.M.; Korean Sepsis Alliance (KSA) investigators. Culture-negative sepsis may be a different entity from culture-positive sepsis: A prospective nationwide multicenter cohort study. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Al Rifaie, R.; Subedi, K.; Coletti, C. Comparative Analysis of Bacteremic and Non-bacteremic Sepsis: A Retrospective Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e76418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.Q.; Zhang, W.Y.; Fu, J.J.; Fang, X.Z.; Gao, C.G.; Li, C.; Yao, L.; Li, Q.L.; Yang, X.B.; Ren, L.H.; et al. Viral sepsis: Diagnosis, clinical features, pathogenesis, and clinical considerations. Mil. Med. Res. 2024, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; Mcintyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, e1063–e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, E.D.; Hirschmann, J.V. Transient bacteremia and endocarditis prophylaxis. A review. Medicine 1977, 56, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takai, S.; Kuriyama, T.; Yanagisawa, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Karasawa, T. Incidence and bacteriology of bacteremia associated with various oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2005, 99, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockhart, P.B.; Brennan, M.T.; Sasser, H.C.; Fox, P.C.; Paster, B.J.; Bahrani-Mougeot, F.K. Bacteremia associated with toothbrushing and dental extraction. Circulation 2008, 117, 3118–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horliana, A.C.; Chambrone, L.; Foz, A.M.; Artese, H.P.; Rabelo, M.S.; Pannuti, C.M.; Romito, G.A. Dissemination of periodontal pathogens in the bloodstream after periodontal procedures: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bayer, A.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Daum, R.S.; Fridkin, S.K.; Gorwitz, R.J.; Kaplan, S.L.; Karchmer, A.W.; Levine, D.P.; Murray, B.E.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, e18e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddour, L.M.; Wilson, W.R.; Bayer, A.S.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Tleyjeh, I.M.; Rybak, M.J.; Barsic, B.; Lockhart, P.B.; Gewitz, M.H.; Levison, M.E.; et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: Diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015, 132, 1435e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis 2016, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.W.X.; Luo, J.; Fridman, D.J.; Lee, S.M.; Johnstone, J.; Schwartz, K.L.; Diong, C.; Patel, S.N.; MacFadden, D.; Langford, B.; et al. Follow-up blood cultures do not reduce mortality in hospitalized patients with Gram-negative bloodstream infection: A retrospective population-wide cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Lee, S.U.; Park, B.; Jeon, K.; Park, S.; Suh, G.Y.; Oh, D.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, M.H.; Lee, H.; et al. Clinical effects of bacteremia in sepsis patients with community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Mirrett, S.; Reller, L.B.; Weinstein, M.P. Detection of bloodstream infections in adults: How many blood cultures are needed? J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 3546–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balk, R.A. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS): Where did it come from and is it still relevant today? Virulence 2014, 5, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.Q. SIRS in the Time of Sepsis-3. Chest 2018, 153, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefzik, R.; Hahn, B.; Schneider-Lindner, V. Dissecting contributions of individual systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria from a prospective algorithm to the prediction and diagnosis of sepsis in a polytrauma cohort. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1227031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinical Study | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristic | 510k | UGANDA | SeptAsTERS | |

| Total number | 305 | 137 * | 59 | ND |

| Age, median (range) | 58 (18–90) | 46 (18–86) | 66 (30–84) | 0.072 |

| [missing: 12] | ||||

| Sex (M/F) | 172 (56%) M | 65 (47%) M | 38 (64%) M | 0.064 |

| 133 (44%) F | 72 (53%) F | 21 (36%) F | ||

| (p = 0.037) | (p = 0.038) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | p < 0.00001 | |||

| White | 189 (61.9%) | 0 | 59 (100%) | |

| African or African heritage | 82 (27%) | 137 (100%) | 0 | |

| Asian | 14 (4.6%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Hispanic | 16 (5.2%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Other/Unknown | 4 (1.3%) | 0 | 0 | |

| SOFA, median (observed range) | 5 (0–20) | 2 (1–10) | 5 (1–18) | <0.001 |

| missing values | 34 (11.1%) | none | none | |

| Sepsis | 81 1 | 134 2 | 34 1 | ND |

| SIRS | 224 | 3 * | 25 | ND |

| SeptiScore Band | BC(+) Sepsis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 510k | SeptAsTERS | Uganda + Ghana | All Cohorts | |

| Band 4 | 34 (70.8%) | 12 (80.0%) | 20 (90.9%) | 66 (77.7%) |

| Band 3 | 9 (18.8%) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (4.6%) | 11 (12.9%) |

| Band 2 | 5 (10.4%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (4.6%) | 8 (9.4%) |

| Band 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BC(+) sepsis/all patients | 48/305 (15.7%) | 15/59 (25.4%) | 22/142 (15.5%) | 85/506 (16.8%) |

| Gram stain: (+)/(−)/mixed | 20/22/6 * | 6/9/0 ** | 11/11/0 *** | 37/42/6 |

| SeptiCyte RAPID Band | Sepsis and BC(+) | SIRS | Total Patients | LR+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band 4 (7.4–15) | 66 | 34 | 100 | 5.88 |

| Band 3 (6.2–7.3) | 11 | 50 | 61 | 0.66 |

| Band 2 (5.0–6.1) | 8 | 78 | 86 | 0.31 |

| Band 1 (0–4.9) | 0 | 95 | 95 | 0 |

| Total | 85 | 257 | 342 |

| No Prior Blood Culture Result | Previous Blood Culture Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||

| SeptiScore | High | • Take initial and follow-up BC sets • Increased efforts to isolate pathogen • Use syndromic panels • Look for possible source | • Repeat SeptiCyte RAPID after 48–72 h if symptomatic or deteriorating • Repeat blood cultures to rule out metastatic spread | • Increased efforts to isolate pathogen • Take additional blood culture sets • Use syndromic panels • Look for possible source |

| Low | • Consider alternate diagnoses • Repeat SeptiCyte RAPID if patient deteriorating | • Rule out contamination • Repeat SeptiCyte RAPID. If, upon repeat, a high SeptiScore obtained, then repeat blood cultures. If another low SeptiScore obtained, then consider alternate diagnosis | • Low likelihood of follow up blood cultures being positive unless patient deteriorates • Consider alternate diagnosis | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Navalkar, K.A.; Wheelock, A.; Gregory, M.; Clark, D.; Kibuuka, H.; Okello, S.; Atukunda, S.; Wailagala, A.; Waitt, P.; Kakooza, F.; et al. Likelihood of Blood Culture Positivity Using SeptiCyte RAPID. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031231

Navalkar KA, Wheelock A, Gregory M, Clark D, Kibuuka H, Okello S, Atukunda S, Wailagala A, Waitt P, Kakooza F, et al. Likelihood of Blood Culture Positivity Using SeptiCyte RAPID. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031231

Chicago/Turabian StyleNavalkar, Krupa A., Alyse Wheelock, Melissa Gregory, Danielle Clark, Hannah Kibuuka, Stephen Okello, Sharon Atukunda, Abdullah Wailagala, Peter Waitt, Francis Kakooza, and et al. 2026. "Likelihood of Blood Culture Positivity Using SeptiCyte RAPID" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031231

APA StyleNavalkar, K. A., Wheelock, A., Gregory, M., Clark, D., Kibuuka, H., Okello, S., Atukunda, S., Wailagala, A., Waitt, P., Kakooza, F., Oduro, G., Adams, N., Dietrich, M., von der Forst, M., Schultz, M. J., Aggarwal, N. R., Greenberg, J. A., Cermelli, S., Yager, T. D., & Brandon, R. B. (2026). Likelihood of Blood Culture Positivity Using SeptiCyte RAPID. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031231