Augmented and Mixed Reality in Cardiac Surgery: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

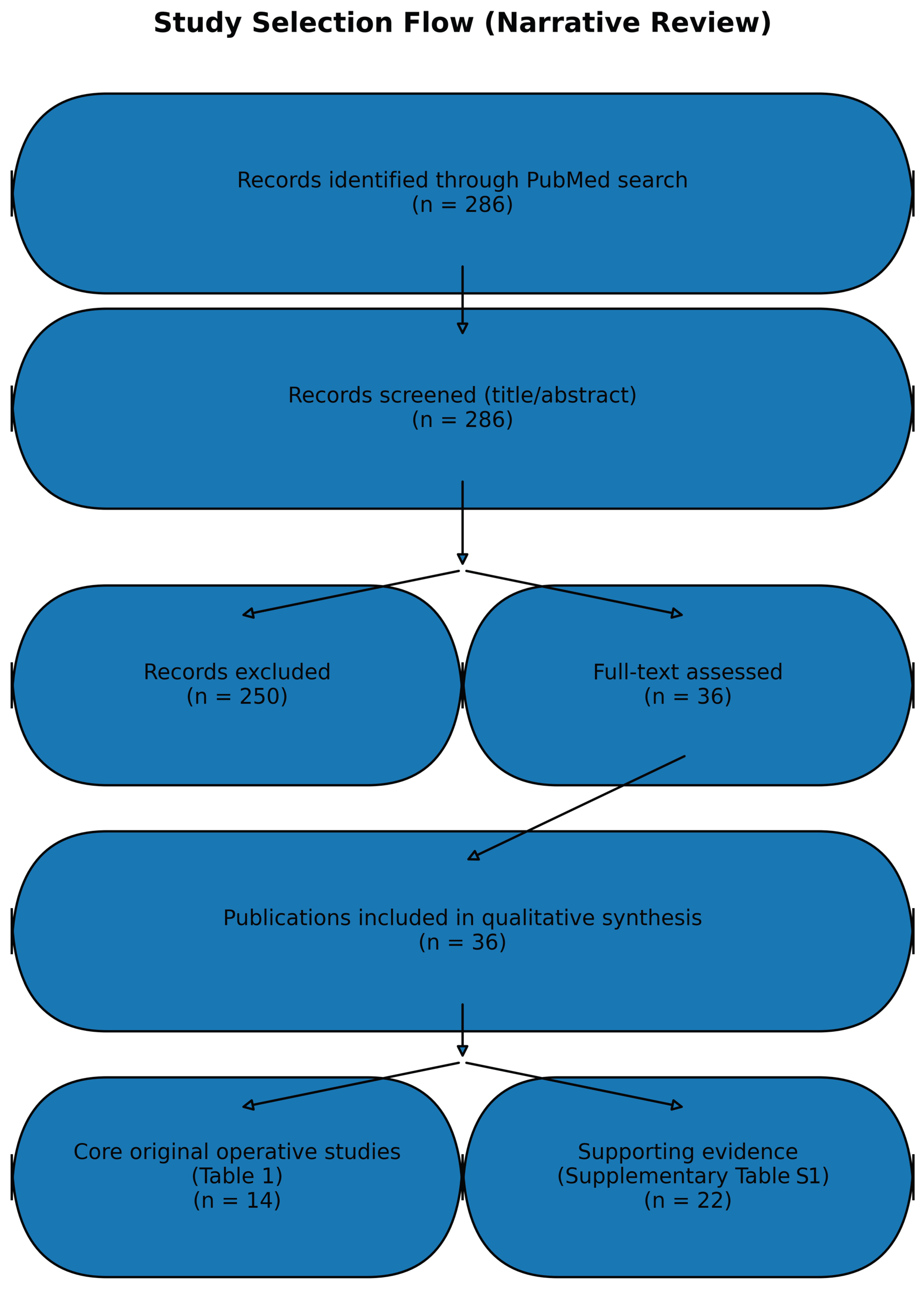

2. Materials and Methods

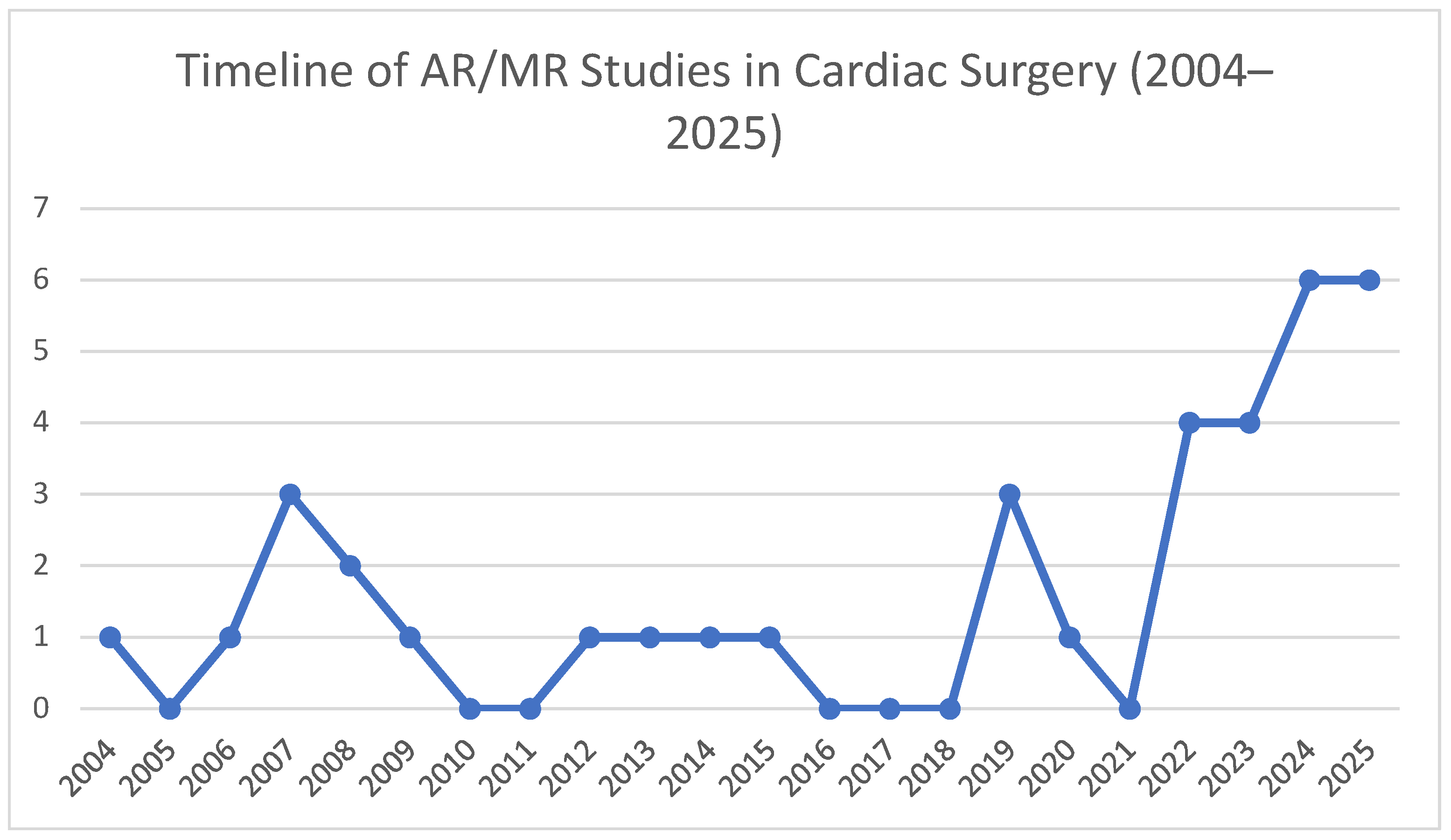

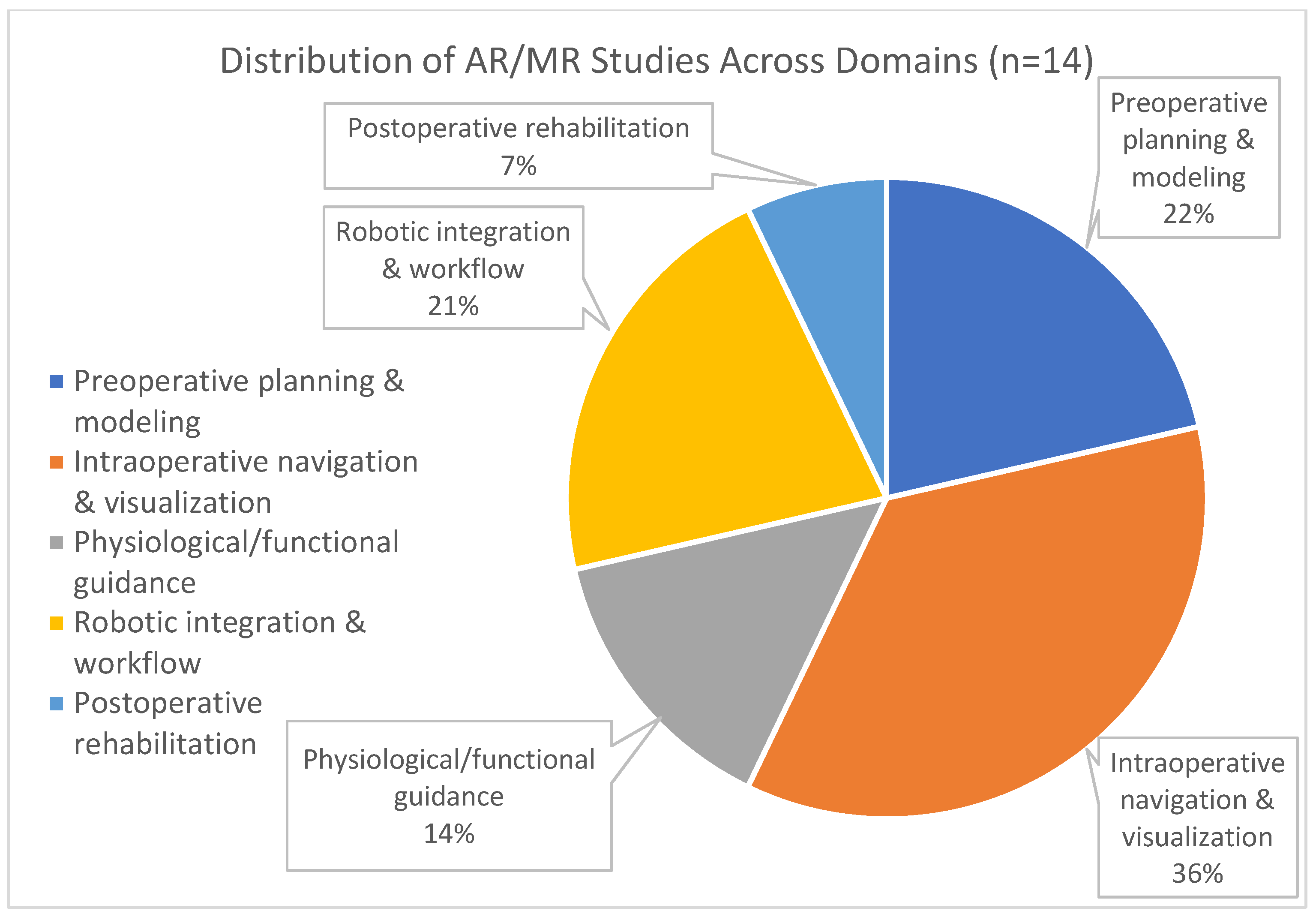

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Preoperative Planning and Patient-Specific Modelling

4.2. Intraoperative Navigation and Visualization

4.3. Physiological and Functional Guidance

4.4. Robotic Integration and Workflow Optimization

4.5. Postoperative Rehabilitation

4.6. Cross-Cutting Limitations and Implementation Considerations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | Augmented reality |

| AR/MR | Augmented reality/Mixed reality |

| CABG | Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| LAD | Left anterior descending (coronary artery) |

| MICS | Minimally invasive cardiac surgery |

| MR | Mixed reality |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| RCT | Randomized clinical trial |

| Suppl. | Supplementary |

| TECAB | Totally endoscopic coronary artery bypass |

| TEE | Transesophageal echocardiography |

| VR | Virtual reality |

| XR | Extended reality |

References

- De Cannière, D.; Wimmer-Greinecker, G.; Cichon, R.; Gulielmos, V.; Van Praet, F.; Seshadri-Kreaden, U.; Falk, V. Feasibility, safety, and Efficacy of Totally Endoscopic Coronary Artery Bypass grafting: Multicenter European Experience. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007, 134, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ender, J.; Končar-Zeh, J.; Mukherjee, C.; Jacobs, S.; Borger, M.A.; Viola, C.; Gessat, M.; Fassl, J.; Mohr, F.W.; Falk, V. Value of Augmented Reality-Enhanced Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE) for Determining Optimal Annuloplasty Ring Size during Mitral Valve Repair. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2008, 86, 1473–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, A.A.; Vardanyan, R.; Lopuszko, A.; Alt, C.; Stoffels, I.; Schmack, B.; Ruhparwar, A.; Zhigalov, K.; Zubarevich, A.; Weymann, A. Virtual and Augmented Reality in Cardiac Surgery. Braz. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 37, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, A.H.; El Mathari, S.; Abjigitova, D.; Maat, A.P.M.; Taverne, Y.J.J.; Bogers, A.J.C.; Mahtab, E.A. Current and Future Applications of Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Reality in Cardiothoracic Surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 113, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacha, J.; Krawczyk, K.; Bugajski, J.; Stanisz, M.; Feusette, P.; Gierlotka, M. MitraClip Implantation in Holography. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, e107–e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aye, W.M.M.; Kiraly, L.; Kumar, S.S.; Kasivishvanaath, A.; Gao, Y.; Kofidis, T. Mixed Reality (Holography)-Guided Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery-A Novel Comparative Feasibility Study. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanchahal, S.; Arjomandi Rad, A.; Naruka, V.; Chacko, J.; Liu, G.; Afoke, J.; Miller, G.; Malawana, J.; Punjabi, P. Mitral Valve Surgery Assisted by Virtual and Augmented reality: Cardiac Surgery at the Front of Innovation. Perfusion 2022, 39, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linte, C.A.; Wierzbicki, M.; Moore, J.; Guiraudon, G.; Jones, D.L.; Peters, T.M. On Enhancing Planning and Navigation of Beating-Heart Mitral Valve Surgery Using Pre-operative Cardiac Models. In Proceedings of the 2007 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Lyon, France, 22–26 August 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.W.; Moore, J.; Peters, T.; Bainbridge, D.; McCarty, D.; Guiraudon, G.M.; Wedlake, C.; Lang, P.; Rajchl, M.; Currie, M.E.; et al. Augmented Reality Image Guidance Improves Navigation for Beating Heart Mitral Valve Repair. Innovations 2012, 7, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauernschmitt, R.; Feuerstein, M.; Traub, J.; Schirmbeck, E.U.; Klinker, G.; Lange, R. Optimal Port Placement and Enhanced Guidance in Robotically Assisted Cardiac Surgery. Surg. Endosc. 2006, 21, 684–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, D.; Jones, D.L.; Guiraudon, G.M.; Peters, T.M. Ultrasound Image and Augmented Reality Guidance for Off-pump, Closed, Beating, Intracardiac Surgery. Artif. Organs 2008, 32, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, Z.; Berg, S.; Sjökvist, S.; Gustafsson, T.; Carleberg, P.; Uppsäll, M.; Wren, J.; Ahn, H.; Smedby, Ö. Real-time Intraoperative Visualization of Myocardial Circulation Using Augmented Reality Temperature Display. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 29, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyanov, D.; Yang, G.Z. Stabilization of Image Motion for Robotic Assisted Beating Heart Surgery. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention: MICCAI International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Brisbane, Australia, 29 October–2 November 2007; Volume 10, pp. 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, N.G.; Namazinia, M.; Hajiabadi, F.; Mazlum, S.R. The Efficacy of Phase I Cardiac Rehabilitation Training Based on Augmented Reality on the self-efficacy of Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Graft surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 15, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grab, M.; Hundertmark, F.; Thierfelder, N.; Fairchild, M.; Mela, P.; Hagl, C.; Grefen, L. New Perspectives in Patient Education for Cardiac Surgery Using 3D-printing and Virtual Reality. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1092007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minga, I.; Al-Ani, M.A.; Moharem-Elgamal, S.; House, A.V.; Abuzaid, A.S.; Masoomi, M.; Mangi, S. Use of Virtual Reality and 3D Models in Contemporary Practice of Cardiology. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2024, 26, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peoples, J.J.; Gianluigi Bisleri Ellis, R.E. Deformable Multimodal Registration for Navigation in Beating-Heart Cardiac Surgery. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2019, 14, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segars, W.P.; Veress, A.I.; Sturgeon, G.M.; Samei, E. Incorporation of the Living Heart Model into the 4-D XCAT Phantom for Cardiac Imaging Research. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 2019, 3, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, J.D.; Pawlowski, J.; Peruga, J.Z.; Kaminski, J.; Lipiec, P. First-in-man Experience with real-time Holographic Mixed Reality Display of three-dimensional Echocardiography during Structural intervention: Balloon Mitral Commissurotomy. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 41, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, R.; Oliveira, A.; Terroso, D.; Vilaça, A.; Veloso, R.; Marques, A.; Pereira, J.; Coelho, L. Mixed Reality in the Operating Room: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Syst. 2024, 48, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.; Turna, A.; Stringfellow, T.D.; Jones, G.G. Uses of Augmented Reality in Surgical Consent and Patient Education—A Systematic Review. PLoS Digit. Health 2025, 4, e0000777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arujuna, A.V.; Housden, R.J.; Ma, Y.; Rajani, R.; Gao, G.; Nijhof, N.; Cathier, P.; Bullens, R.; Gijsbers, G.; Parish, V.; et al. Novel System for Real-Time Integration of 3-D Echocardiography and Fluoroscopy for Image-Guided Cardiac Interventions: Preclinical Validation and Clinical Feasibility Evaluation. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2014, 2, 1900110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finos, K.; Datta, S.; Sedrakyan, A.; Milsom, J.W.; Pua, B.B. Mixed Reality in Interventional radiology: A Focus on First Clinical Use of XR90 Augmented reality-based Visualization and Navigation Platform. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2024, 21, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annabestani, M.; Olyanasab, A.; Mosadegh, B. Application of Mixed/Augmented Reality in Interventional Cardiology. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, A.H.; Mank, Q.; Tuzcu, A.S.; Hofman, J.; Siregar, S.; Maat, A.; Mottrie, A.; Kluin, J.; De Backer, P. Artificial Intelligence-assisted Augmented Reality Robotic Lung Surgery: Navigating the Future of Thoracic Surgery. JTCVS Tech. 2024, 26, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshanfar, M.; Salimi, M.; Kaboodrangi, A.H.; Jang, S.-J.; Sinusas, A.J.; Wong, S.-C.; Mosadegh, B. Advanced Robotics for the Next-Generation of Cardiac Interventions. Micromachines 2025, 16, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, A.; Hokmabadi, A.; Bi, N.; Wijesinghe, I.; Nix, M.G.; Petersen, S.E.; Frangi, A.F.; Taylor, Z.A.; Gooya, A. DragNet: Learning-based Deformable Registration for Realistic Cardiac MR Sequence Generation from a Single Frame. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 83, 102678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anabtawi, M.; Shabir, D.; Padhan, J.; Al-Ansari, A.; Aboumarzouk, O.M.; Deng, Z.; Navkar, N.V. A Holographic Telementoring System Depicting Surgical Instrument Movements for real-time Guidance in Open Surgeries. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 256, 108396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitnes, J.O.; Klæboe, L.G.; Karlsen, J.S.; Urheim, S. Mitral Valve Analysis Using a Novel 3D Holographic display: A Feasibility Study of 3D Ultrasound Data Converted to a Holographic Screen. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 31, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.Y.; Onuma, Y.; Złahoda-Huzior, A.; Kageyama, S.; Dudek, D.; Wang, Q.; Lim, R.P.; Garg, S.; Poon, E.K.W.; Puskas, J.; et al. Merging Virtual and Physical experiences: Extended Realities in Cardiovascular Medicine. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3311–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Wolff, G.; Wernly, B.; Bruno, R.R.; Franz, M.; Schulze, P.C.; Silva, J.N.A.; Silva, J.R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Kelm, M. Virtual and Augmented Reality in Cardiovascular Care. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, S.G.; Kettler, D.T.; Novotny, P.M.; Plowes, R.D.; Howe, R.D. Robotic Motion Compensation for Beating Heart Intracardiac Surgery. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2009, 28, 1355–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riad, A.; Hadid, M.; Elomri, A.; Rejeb, M.A.; Qaraqe, M.; Dakua, S.P.; Jaber, A.R.; Al-Ansari, A.; Aboumarzouk, O.M.; EL Omri, A. Advancements and Challenges in Robotic Surgery: A Holistic Examination of Operational Dynamics and Future Directions. Surg. Pract. Sci. 2025, 22, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, X. Perceptions and Experiences of Commercial Virtual Reality Games in Early Postoperative Rehabilitation among Cardiac Surgical patients: A Qualitative Study. Digit. Health 2025, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhaiber, J.H. Augmented Reality in Surgery. Arch. Surg. 2004, 139, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.; Saha, N.; Gadow, V.; Harik, R.; Ryu, J. Role of Extended Reality (XR) Technologies in Maintenance operations: Trends, challenges, and Integration in Industry 4.0. Manuf. Lett. 2025, 44, 1545–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Bruno, A.; Lombardo, M.; Muti, P. Echocardiographic Assessment of Mitral Valve Prolapse Prevalence before and after the Year 1999: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, L.A.; Levy, D.; Levine, R.A.; Larson, M.G.; Evans, J.C.; Fuller, D.L.; Lehman, B.; Benjamin, E.J. Prevalence and Clinical Outcome of Mitral-Valve Prolapse. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, D.; Iliakis, P.; Tatakis, F.; Thomopoulos, K.; Dimitriadis, K.; Tousoulis, D.; Tsioufis, K. Wearable Blood Pressure Measurement Devices and New Approaches in Hypertension management: The Digital Era. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2022, 36, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Evidence Category | Ref | First Author, Year | Study Type | Setting/Model | Surgical Indication | AR/MR Modality | Accuracy/Outcome | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Original clinical evidence (human studies) | ||||||||

| [1] | De Cannière, 2007 | Multicenter clinical series | Human | Totally endoscopic CABG | Endoscopic/robotic | Procedural feasibility, patency | Demonstrated safety, feasibility in 148 pts | |

| [2] | Ender, 2008 | Clinical feasibility | Human | Mitral valve repair | AR-enhanced TEE | Ring size accuracy | Improved sizing without time penalty | |

| [5] | Sacha, 2022 | Clinical case | Human | MitraClip implantation | MR holography | Technical success | First-in-human demonstration of MR in MitraClip | |

| [6] | Winn, 2025 | Comparative feasibility | Human | Minimally invasive cardiac surgery | MR holography | Task completion, workflow | MR reduced cognitive load, improved spatial awareness | |

| [7] | Nanchahal, 2022 | Clinical feasibility | Human | Mitral valve surgery | VR/AR headset guidance | Integration success | Enabled enhanced anatomical visualization | |

| [12] | Szabó, 2013 | Clinical feasibility | Human | Perfusion mapping | AR temperature overlay | Perfusion visualization | Enabled intraoperative myocardial perfusion assessment | |

| [14] | Ghlichi Moghaddam, 2023 | RCT | Human | CABG rehabilitation | AR-based rehab training | Self-efficacy scores | Significant improvement vs. control | |

| (B) Preclinical/technical evidence (phantom/animal/simulation; translational pilot where applicable) | ||||||||

| [8] | Linte, 2007 | Preclinical | Beating-heart phantom | Mitral valve surgery | VR/AR overlays | ~5 mm registration error | Improved spatial orientation | |

| [9] | Chu, 2012 | Preclinical + human pilot | Pig + clinical | Beating-heart mitral valve repair | AR navigation | Navigation accuracy | Improved repair navigation and tool positioning | |

| [10] | Bauernschmitt, 2006 | Preclinical | Phantom | Robotic cardiac surgery | AR port placement | ~2–5 mm accuracy | Optimized trajectories, avoided collisions | |

| [11] | Bainbridge, 2008 | Preclinical | Animal | Off-pump intracardiac surgery | Ultra-sound-based AR | Tool-target alignment | Feasible guidance without open access | |

| [13] | Stoyanov, 2007 | Preclinical | TECAB in vivo + simulation | Beating-heart surgery | Motion-stabilized AR | Motion compensation | Stabilized view improved precision tasks | |

| (C) Review evidence | ||||||||

| [3] | Rad, 2022 | Narrative review with cases | Mixed | Cardiac surgery | VR/AR plat-forms | N/A | Summarized applications, technical aspects | |

| [4] | Sadeghi, 2020 | Narrative review | N/A | Cardiothoracic surgery | XR | N/A | Highlighted current and future uses |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sarantopoulos, A.; Marinakis, M.; Schizas, N.; Iliopoulos, D. Augmented and Mixed Reality in Cardiac Surgery: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031224

Sarantopoulos A, Marinakis M, Schizas N, Iliopoulos D. Augmented and Mixed Reality in Cardiac Surgery: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031224

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarantopoulos, Andreas, Maria Marinakis, Nikolaos Schizas, and Dimitrios Iliopoulos. 2026. "Augmented and Mixed Reality in Cardiac Surgery: A Narrative Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031224

APA StyleSarantopoulos, A., Marinakis, M., Schizas, N., & Iliopoulos, D. (2026). Augmented and Mixed Reality in Cardiac Surgery: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031224