1. Introduction

Severe aortic stenosis (AS) is a progressive and life-threatening disease if left untreated [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has become an established, life-prolonging treatment for individuals with severe aortic stenosis [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. During TAVR, unfractionated heparin (UFH) is routinely administered intravenously to prevent thromboembolic complications associated with large-bore arterial access, catheter manipulation, and valve deployment. Unlike percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or diagnostic coronary angiography, where clear evidence-based guidelines exist for heparin dosing and target activated clotting times (ACT) [

8], current recommendations for anticoagulation during TAVR are largely expert consensus and not supported by high-quality evidence [

9]. Previous recommendations have suggested weight-adjusted dosing of UFH with a target ACT greater than 300 s [

10]. However, other studies and recent recommendations have reported that an ACT target range of 250 to 300 s during TAVR procedures might be considered [

9,

11]. Current evidence supports the use of ACT-guided heparin administration, which has been associated with favourable safety outcomes [

12]. Consequently, the heparin dose, ACT targets, and the use of reversal agents such as protamine vary considerably among operators and centers, resulting in marked heterogeneity in clinical practice. The same uncertainty applies to dosing adjustments in obese patients, where higher doses of heparin are often administered empirically, yet no specific guidelines exist to direct these practices.

Peri-procedural stroke is a serious complication of TAVR. Although stroke rates after TAVR are generally lower than those observed after surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) [

13], it remains clinically significant and is associated with a two- to nine-fold increase in mortality [

14]. These events underscore the importance of optimizing procedural strategies, including anticoagulation management, to minimize thromboembolic risk while maintaining safety.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the association between intraprocedural UFH dosing, ACT values, and peri-procedural stroke risk in the overall population of patients undergoing TAVR, and to compare the heparin dose administered, corresponding ACT values, and peri-procedural stroke risk between obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and non-obese patients undergoing TAVR.

2. Methods

This retrospective single-center clinical registry study was performed at Clinique Pasteur in Toulouse, France. The dataset included all consecutive patients who underwent TAVR for severe AS between 2022 and 2024 using either balloon-expandable valves (Sapien 3, Sapien 3 Ultra, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA; Colibri, Colibri Heart Valve, Broomfield, CO, USA; and MyVal, Meril Life Sciences, Vapi, Gujarat, India) or self-expandable valves (Evolut R, Evolut Pro, Evolut Pro+, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA; Navitor, Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA; and ACURATE neo, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA). Eligibility for TAVR was assessed according to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for valvular heart disease [

3] and final treatment decisions were made by a multidisciplinary Heart Team. Patients receiving ongoing oral anticoagulation, those with history of atrial fibrillation, and individuals undergoing valve in valve or Transcatheter Aortic Valve (TAV) in TAV procedures were excluded from the current analysis. The study included patients undergoing TAVR at Clinique Pasteur whose clinical and procedural data were recorded in the national FRANCE TAVI registry. This study is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement, and the completed STROBE checklist is provided in the

Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table S1). The study population had a mean age of 82 ± 6 years, and 56% were male. Baseline demographic, clinical, and echocardiographic variables were collected for all included patients, and baseline characteristics of the overall cohort and according to BMI group are summarized in

Table 1.

The primary endpoint was the incidence of peri-procedural stroke in the overall population of patients undergoing TAVR, with a prespecified stratified analysis according to body mass index (BMI ≥ 30 vs. <30 kg/m2). Stroke events were evaluated during in-hospital follow-up and were limited to events occurring before discharge. Stroke events were assessed and first identified based on clinical suspicion by the treating cardiologist before hospital discharge, with neurological assessment performed only after the initial clinical evaluation and suspicion of stroke by the treating physician. They were subsequently confirmed by cerebral imaging, consisting of computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and formal neurologist evaluation. Formal stroke severity scales, including the NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and modified Rankin Scale (mRS), were not systematically recorded in the registry. Secondary endpoints included peri-procedural data (including procedure duration, heparin dose [U/kg], activated clotting time [ACT, seconds], and protamine administration according to BMI group). In routine practice at our center, UFH was administered as an initial fixed bolus according to BMI category (typically 3000 IU in patients with BMI < 30 kg/m2 and 5000 IU in patients with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Additional UFH boluses were given at the operator’s discretion based on ACT results and procedural duration. ACT was first measured approximately 15 min after the initial UFH bolus and was rechecked if the procedure was prolonged or if initial ACT values were considered subtherapeutic. In general, ACT values around or below 200 s were considered subtherapeutic and could prompt additional UFH administration at the operator’s discretion. Total UFH dose (U/kg) reflects the sum of the initial and any additional boluses administered during the procedure.

Other secondary clinical outcomes included in-hospital and 1-year mortality, permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation, and Safety outcomes (major vascular complications, life-threatening bleeding, major bleeding, coronary obstruction occurring during the procedure and peri-procedural myocardial infarction (MI)). In addition, a subgroup analysis was performed to assess stroke risk according to ACT values > 250 s versus ≤ 250 s. Clinical and procedural outcomes, including device success, bleeding, and vascular complications, were defined according to the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 (VARC-2) criteria.

3. Statistical Analysis

Categorical and binary variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and group comparisons were performed using the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate.

The Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to evaluate differences in the distribution of continuous variables. Variables demonstrating a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation and were compared using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. Continuous variables that did not follow a normal distribution are expressed as median with interquartile range and were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Subgroup analysis was performed to assess stroke risk according to ACT values. Device success was evaluated as a key procedural endpoint because anticoagulation intensity may influence intra-procedural thrombotic complications, procedural performance, and the need for additional maneuvers, all of which are captured by VARC-defined device success. In addition, given the low number of stroke events, multivariable modeling for stroke was not feasible, whereas device success occurred more frequently and allowed exploratory adjusted analyses. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to determine predictors of device success. A backward stepwise selection approach was applied, incorporating variables that showed a p-value < 0.20 in the univariable analysis. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p-value below 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 29.0.2.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics

The analysis comprised 1045 patients who underwent TAVR, comprising 827 patients with a BMI < 30 and 218 patients with a BMI ≥ 30. In the overall study population, the mean age was 82 years and 56% of patients were male. The mean BMI was 27 kg/m

2, with mean BMI values of 25 kg/m

2 in the BMI < 30 group and 34 kg/m

2 in the BMI ≥ 30 group. Baseline characteristics are summarized in

Table 1 and

Supplementary Table S2. Both study groups exhibited high rates of cardiovascular comorbidities. Patients in the higher BMI group had significantly higher rates of hypertension (87% vs. 72%,

p < 0.001) and dyslipidemia (34% vs. 20%,

p < 0.001), whereas a history of prior cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack was more frequent in the lower BMI group (8% vs. 3%,

p = 0.021). The aortic valve area (AVA) was slightly smaller in patients with lower BMI (0.79 cm

2 vs. 0.82 cm

2,

p = 0.017), while mean transvalvular gradients were similar between groups (49 mmHg vs. 50 mmHg,

p = 0.155). The EuroscoreII was modestly higher in the BMI < 30 group (median 2.45 vs. 2.32,

p = 0.022). There were no significant differences in the prevalence of coronary artery disease between the groups (41% vs. 38%,

p = 0.401). The rate of concomitant pre-TAVR PCI was similar as well, occurring in 22% of patients in the BMI ≥ 30 group versus 25% in the BMI < 30 group (

p = 0.338). Overall, 81% of patients were treated with aspirin, with no statistically significant difference between the groups (80% vs. 82%,

p = 0.534).

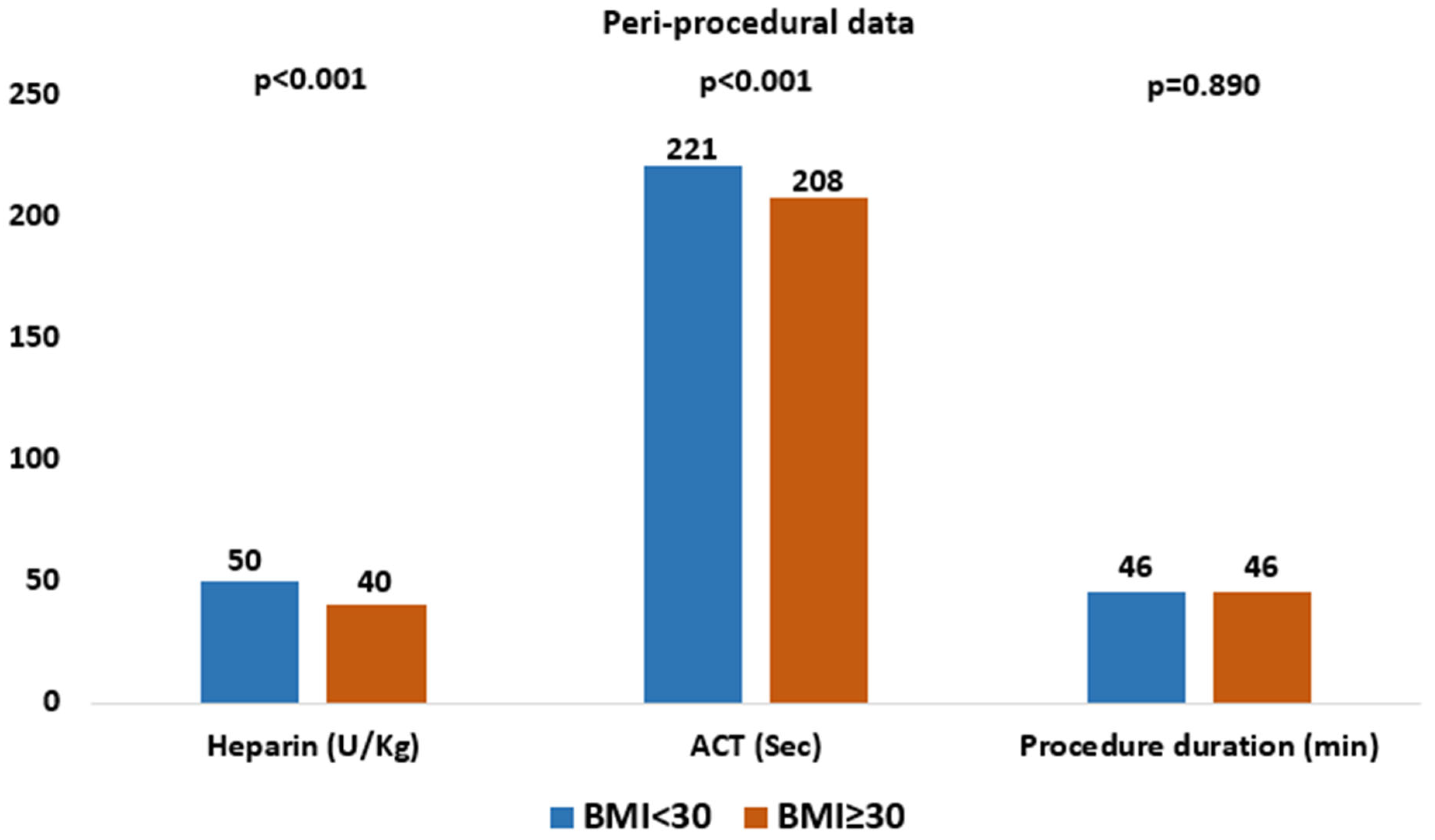

4.2. Periprocedural Data

Periprocedural characteristics are summarized in

Table 2 and

Figure 1. In the overall study population (n = 1045), the majority of patients received self-expanding valves (64%), with a mean procedure duration of 46 min, a mean contrast volume of 82 mL, a mean heparin dose of 47 U/kg, and a mean ACT value of 218 s. The overall median ACT was 212 s (IQR 189–240). ACT values ≥ 250 s were achieved in 19% of patients, and ≥300 s in 7%. Compared with the high BMI group, patients in the low BMI group received a higher mean heparin dose (50 U/kg vs. 40 U/kg,

p < 0.001) and had higher mean ACT values (221 s vs. 208 s,

p < 0.001).

Protamine was not systematically administered to neutralize UFH, its use was low in the overall cohort (1.9%) and did not differ significantly between the study groups (2% vs. 1.3%, p = 0.515). There were no statistically significant differences between groups in the rates of pre-dilatation (24% vs. 21%, p = 0.319), post-dilatation (18% vs. 20%, p = 0.413), valve repositioning (34% vs. 33%, p = 0.762), or the need to implant a second valve during the procedure (1% vs. 0%, p = 0.217).

4.3. Procedural and Clinical Outcomes

Data regarding procedural and clinical outcomes are detailed in

Table 3 and

Figure 2. In the overall population of 1045 patients undergoing TAVR, procedural and clinical outcomes were favorable, with a device success rate of 92%, a low incidence of peri-procedural stroke (1.1%), low in-hospital mortality (0.4%), and a 1-year mortality rate of 3%. Major vascular complications were observed in 2% of patients, life-threatening bleeding in 1%, and major bleeding events in 3.4%. Coronary obstruction and peri-procedural myocardial infarction were rare, occurring in only 0.2% and 0.4% of patients, respectively. When outcomes were analyzed according to BMI, device success rates remained high and comparable between obese and non-obese patients (93% vs. 92%). The incidence of peri-procedural stroke did not differ significantly between the two groups (0.9% vs. 1.2%,

p = 0.711). The absolute risk difference for stroke between BMI groups was 0.29%, corresponding to a relative risk of 1.31 (95% CI 0.29–5.91). Similarly, there were no significant differences in in-hospital mortality (0% vs. 0.5%,

p = 0.586) or 1-year mortality (4% vs. 3%,

p = 0.534). Rates of major vascular complications (0.9% vs. 2%,

p = 0.196), life-threatening bleeding (1% vs. 0.9%,

p = 0.599), and major bleeding (2.7% vs. 3.6%,

p = 0.528) were also comparable between obese and non-obese patients.

A subgroup analysis comparing patients with ACT values above or below 250 s revealed no significant difference in periprocedural stroke rates (1% vs. 1.5%,

p = 0.604) (

Table 4). Multivariable analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of device success (

Table 5). Longer procedure duration (OR 0.981, 95% CI 0.971–0.991;

p < 0.001) and higher contrast volume (OR 0.993, 95% CI 0.987–0.998;

p = 0.010) were independently associated with reduced device success. In contrast, valve repositioning was associated with a higher probability of success (OR 2.382, 95% CI 1.361–4.170;

p = 0.002).

5. Discussion

In this study, the overall population of 1045 patients undergoing TAVR demonstrated high procedural success and favourable short and mid-term clinical outcomes, with low rates of peri-procedural stroke, bleeding complications, vascular complications, and mortality, despite a mean intraprocedural heparin dose of 47 U/kg and a mean ACT value of 218 s. Within this overall cohort, patients were analysed according to BMI < 30 or ≥30. Despite significant differences in heparin dosing and ACT values between groups, procedural characteristics and outcomes, including device success, periprocedural stroke, bleeding, vascular complications, in hospital and 1-year mortality were comparable. A subgroup analysis based on ACT values above or below 250 s showed no significant difference in periprocedural stroke rates. Overall, TAVR demonstrated high procedural success and favourable short and mid-term outcomes regardless of BMI. Multivariable analysis identified that longer procedure duration and higher contrast volume were associated with reduced device success, whereas valve repositioning was associated with a higher likelihood of achieving success.

In contrast to coronary interventions where heparin dosing and ACT targets are well defined and supported by strong clinical evidence [

8,

15], anticoagulation strategies during TAVR remain largely empirical and based on expert consensus [

9]. Previous studies have shown conflicting results regarding the relationship between ACT levels and clinical outcomes during TAVR, with some suggesting higher ACT targets reduce thromboembolic events while others found no clear benefit [

12,

16]. Considerable variability exists between centers and operators regarding heparin dose adjustment and target ACT values, particularly in obese patients [

17,

18]. In our study, despite significant differences in heparin dosing and ACT levels between BMI groups, procedural success and safety outcomes were comparable. These findings suggest that moderate variations in anticoagulation intensity during TAVR may not substantially impact thromboembolic or bleeding risk. One possible explanation is the distinct procedural environment, since TAVR involves manipulation within the aorta and valve annulus, which are large caliber structures with lower thrombotic potential compared to small coronary arteries. Therefore, achieving very high ACT values may be less critical in preventing thromboembolic complications during TAVR. However, given the low number of stroke events and wide confidence intervals, these results should be interpreted with caution, as clinically meaningful differences cannot be excluded. In addition, differences in baseline cerebrovascular risk between BMI groups may have influenced stroke risk and should be considered when interpreting the absence of a detected association. Accordingly, the absence of a detected association should not be interpreted as evidence that no association exists. These results reflect the experience of a single high-volume center in a selected population of patients not receiving chronic oral anticoagulation and without atrial fibrillation. As such, our findings should be considered hypothesis-generating and may inform the design of prospective studies evaluating anticoagulation strategies during TAVR

The findings of this study may have several important clinical implications. The absence of differences in procedural or safety outcomes between obese and non-obese patients despite variations in heparin dosing and ACT values suggests that anticoagulation management during TAVR may not need to be strictly weight adjusted. This supports a more individualized approach rather than a universal target strategy. This individualized approach would consider factors such as baseline coagulation profile, procedural complexity, and bleeding risk. Moreover, since higher ACT levels did not translate into improved outcomes in this study, excessive anticoagulation may not provide additional benefit and could potentially increase bleeding risk, thus increasing the need for protamine administration, which may complicate management if a covered stent becomes necessary. These results highlight the need for standardized, evidence-based anticoagulation protocols in TAVR and emphasize the importance of future prospective trials to define optimal ACT targets and heparin dosing strategies.

This study has important limitations that should be acknowledged. First, as a retrospective observational analysis, the findings may be affected by residual confounding and potential sources of bias. Second, although the study included a relatively large cohort, its single-center design may restrict the applicability of the findings to other institutions with different patient profiles, procedural techniques, and local practice patterns, including differences in practice environment, regional characteristics, and procedural duration [

19]. Third, stroke events may have been under-detected, as identification relied on clinical suspicion during in hospital follow up before discharge rather than systematic neurological assessment. No routine independent neurological evaluation was performed, potentially underestimating minor or non-disabling strokes, and standardized severity scores (NIHSS or modified Rankin Scale) were not available. In addition, neurological events occurring after hospital discharge (e.g., within 30 days) were not systematically captured, which may further underestimate the true stroke incidence. Fourth, some patients from the original database were excluded due to missing data, which could introduce selection bias and slightly limit the applicability of the results. Finally, given the low number of stroke events, the study was underpowered to detect small between-group differences in stroke risk; therefore, modest differences cannot be excluded. Moreover, the imbalance in baseline stroke risk factors between BMI groups may have introduced residual confounding that could not be fully addressed due to the small number of events.

In conclusion, this study suggests that despite differences in heparin dosing and ACT values, procedural characteristics and clinical outcomes of TAVR, including peri-procedural stroke, were low in the overall population and similar between obese and non-obese patients. These results may suggest that variations in intraprocedural anticoagulation management may not significantly affect stroke risk. However, given the low number of stroke events, the absence of a detected association should not be interpreted as evidence that no association exists. Future randomized studies are warranted to define optimal heparin dosing and ACT targets and to establish standardized anticoagulation strategies during TAVR.

6. Clinical Perspectives

There are no clear evidence-based guidelines defining optimal heparin dosing or target activated clotting time (ACT) values during TAVR.

Differences in heparin dosing and ACT values did not impact clinical outcomes, including periprocedural stroke, reassuring operators that real-world anticoagulation variability during TAVR, particularly in obese patients, is unlikely to compromise safety.

Future randomized studies are warranted to define optimal heparin dosing and ACT targets during TAVR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D.B.; methodology, A.M. and L.L.; software, L.L.; validation, Z.A.; formal analysis, Z.A.; investigation, Z.A.; resources, L.B.; data curation, A.C. and L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.A.; writing—review and editing, C.D.B.; visualization, J.I., R.H.-A. and A.A.; supervision, D.T.; project administration, N.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is based on data derived from the FRANCE TAVI registry, a nationwide database that has been authorized by the French Commission on Informatics and Liberty (CNIL). In France, this authorization constitutes the ethical approval required for research involving anonymized registry data (protocol Number: n° 2222005 and protocol approval number 2021-152, approved on 16 December 2021). Because our institution participates in the FRANCE TAVI registry, which is coordinated and overseen by the Société Française de Cardiologie, additional local institutional ethics committee approval was not required for the present analysis.

Informed Consent Statement

Requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design of the study and the use of fully anonymized data.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| TAVR | Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement |

| UFH | Unfractionated heparin |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| ACT | Activated clotting times |

| CVA | Cerebrovascular accident |

References

- Pilgrim, T.; Englberger, L.; Rothenbühler, M.; Stortecky, S.; Ceylan, O.; O’Sullivan, C.J.; Huber, C.; Praz, F.; Buellesfeld, L.; Langhammer, B.; et al. Long-term outcome of elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis as a function of treatment modality. Heart 2015, 101, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carabello, B.A.; Paulus, W.J. Aortic stenosis. Lancet 2009, 373, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahanian, A.; Beyersdorf, F.; Praz, F.; Milojevic, M.; Baldus, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Capodanno, D.; Conradi, L.; De Bonis, M.; De Paulis, R.; et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 75, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, C.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P., 3rd; Gentile, F.; Jneid, H.; Krieger, E.V.; Mack, M.; McLeod, C.; et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021, 143, e72–e227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kapadia, S.R.; Leon, M.B.; Makkar, R.R.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Svensson, L.G.; Kodali, S.; Webb, J.G.; Mack, M.J.; Douglas, P.S.; Thourani, V.H.; et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement compared with standard treatment for patients with inoperable aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2485–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, M.B.; Smith, C.R.; Mack, M.; Miller, D.C.; Moses, J.W.; Svensson, L.G.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Webb, J.G.; Fontana, G.P.; Makkar, R.R.; et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapadia, S.R.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Makkar, R.R.; Svensson, L.G.; Agarwal, S.; Kodali, S.; Fontana, G.P.; Webb, J.G.; Mack, M.; Thourani, V.H.; et al. Long-term outcomes of inoperable patients with aortic stenosis randomly assigned to transcatheter aortic valve replacement or standard therapy. Circulation 2014, 130, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ten Berg, J.; Sibbing, D.; Rocca, B.; Van Belle, E.; Chevalier, B.; Collet, J.P.; Dudek, D.; Gilard, M.; Gorog, D.A.; Grapsa, J.; et al. Management of antithrombotic therapy in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: A consensus document of the ESC Working Group on Thrombosis and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), in collaboration with the ESC Council on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2265–2269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agnihotri, A.; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; American College of Cardiology Foundation; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2012 ACCF/AATS/SCAI/STS expert consensus document on transcatheter aortic valve replacement: Executive summary. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2012, 144, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, E.M.; Friedman, S.K.; Baker, T.M. A review of antithrombotic therapy for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Postgrad. Med. 2013, 125, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernelli, C.; Chieffo, A.; Montorfano, M.; Maisano, F.; Giustino, G.; Buchanan, G.L.; Chan, J.; Costopoulos, C.; Latib, A.; Figini, F.; et al. Usefulness of baseline activated clotting time-guided heparin administration in reducing bleeding events during transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 7, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durko, A.P.; Reardon, M.J.; Kleiman, N.S.; Popma, J.J.; Van Mieghem, N.M.; Gleason, T.G.; Bajwa, T.; O’Hair, D.; Brown, D.L.; Ryan, W.H.; et al. Neurological Complications After Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2109–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansky, A.J.; Ghare, M.I.; Pietras, C. Carotid Disease and Stroke After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 11, e006826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151, e771–e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hokken, T.W.; de Maat, M.P.M.; Van Mieghem, N.M. The Risk for Excessive Anticoagulation with Activated Clotting Time-Guided Monitoring in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Struct. Heart 2024, 9, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangas, G.D.; Lefèvre, T.; Kupatt, C.; Tchetche, D.; Schäfer, U.; Dumonteil, N.; Webb, J.G.; Colombo, A.; Windecker, S.; Ten Berg, J.M.; et al. BRAVO-3 Investigators. Bivalirudin Versus Heparin Anticoagulation in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: The Randomized BRAVO-3 Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 2860–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kassou, B.; Veulemans, V.; Shamekhi, J.; Maier, O.; Piayda, K.; Zeus, T.; Aksoy, A.; Zietzer, A.; Meertens, M.; Mauri, V.; et al. Optimal protamine-to-heparin dosing ratio for the prevention of bleeding complications in patients undergoing TAVR-A multicenter experience. Clin. Cardiol. 2023, 46, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasiak, P.S.; Buchalska, B.; Kowalczyk, W.; Wyszomirski, K.; Krzowski, B.; Grabowski, M.; Balsam, P. The Path of a Cardiac Patient-From the First Symptoms to Diagnosis to Treatment: Experiences from the Tertiary Care Center in Poland. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |