Effect of Different Chemo-Mechanical Shaping Protocols on the Intratubular Penetration of a Bioceramic Sealer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Selection

2.2. Working Length and Glide Path

2.3. Shaping

2.4. Final Activation of Irrigants

2.5. Canal Obturation

2.6. Sample Preparation for CLSM Analysis

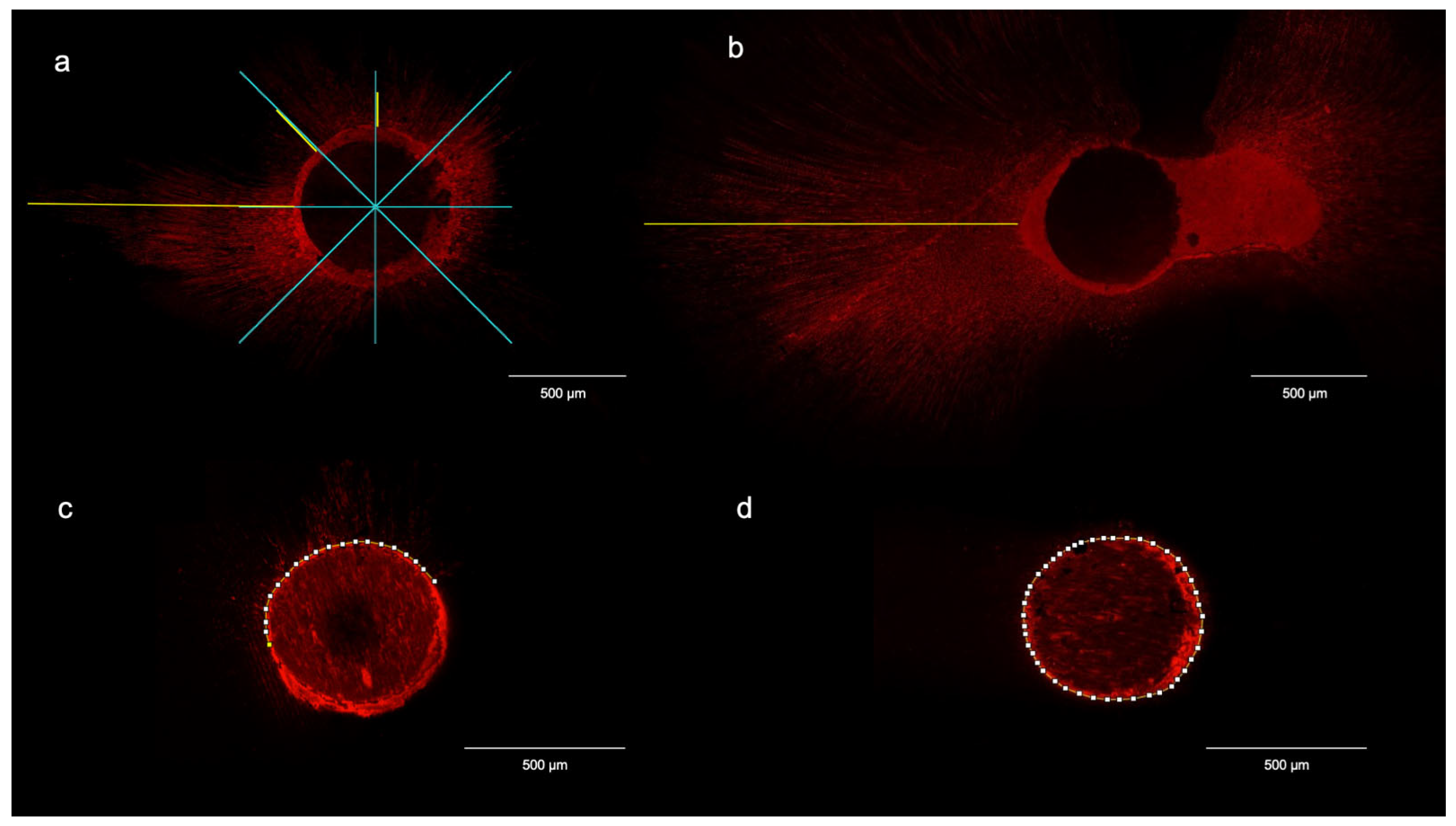

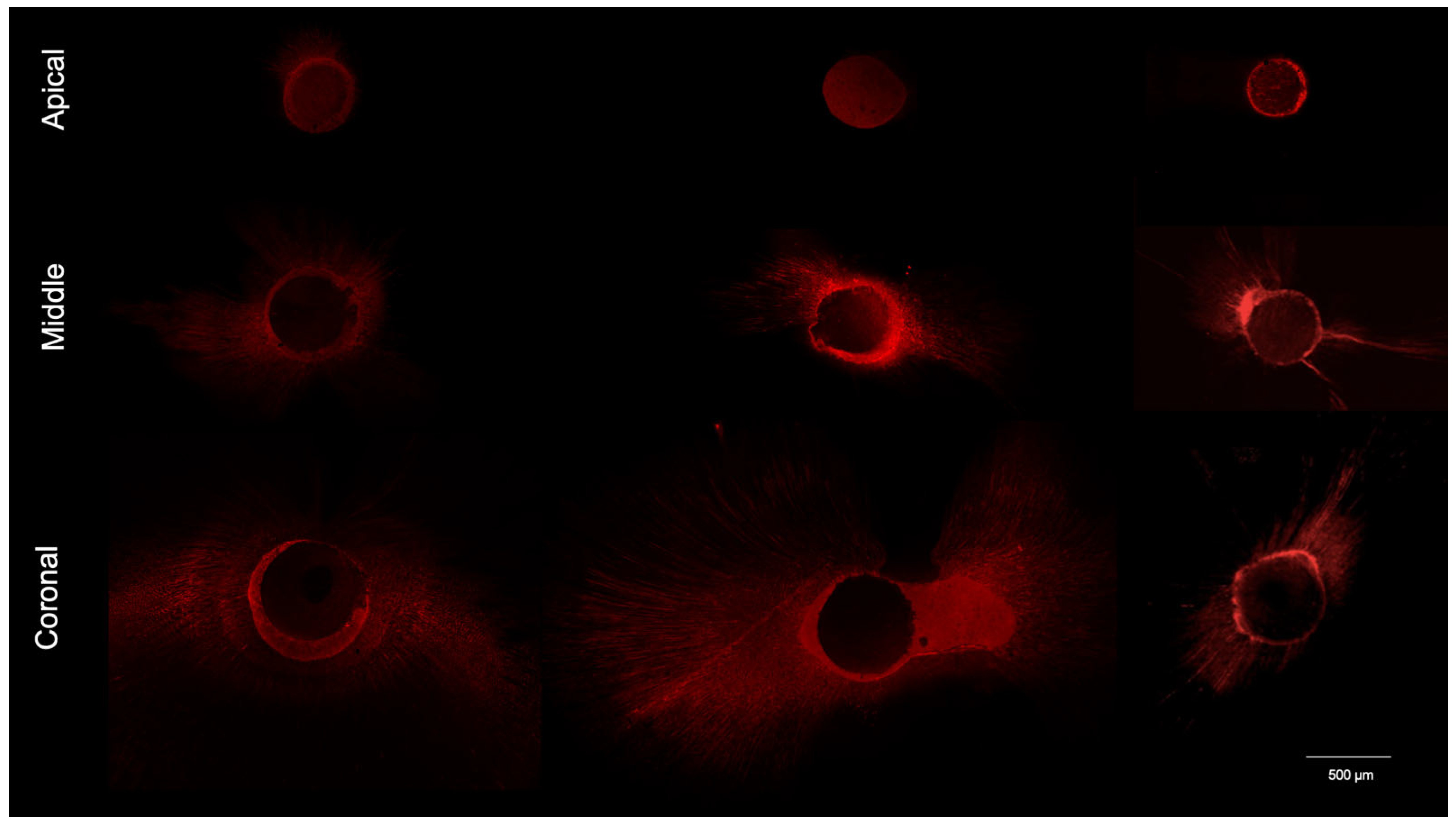

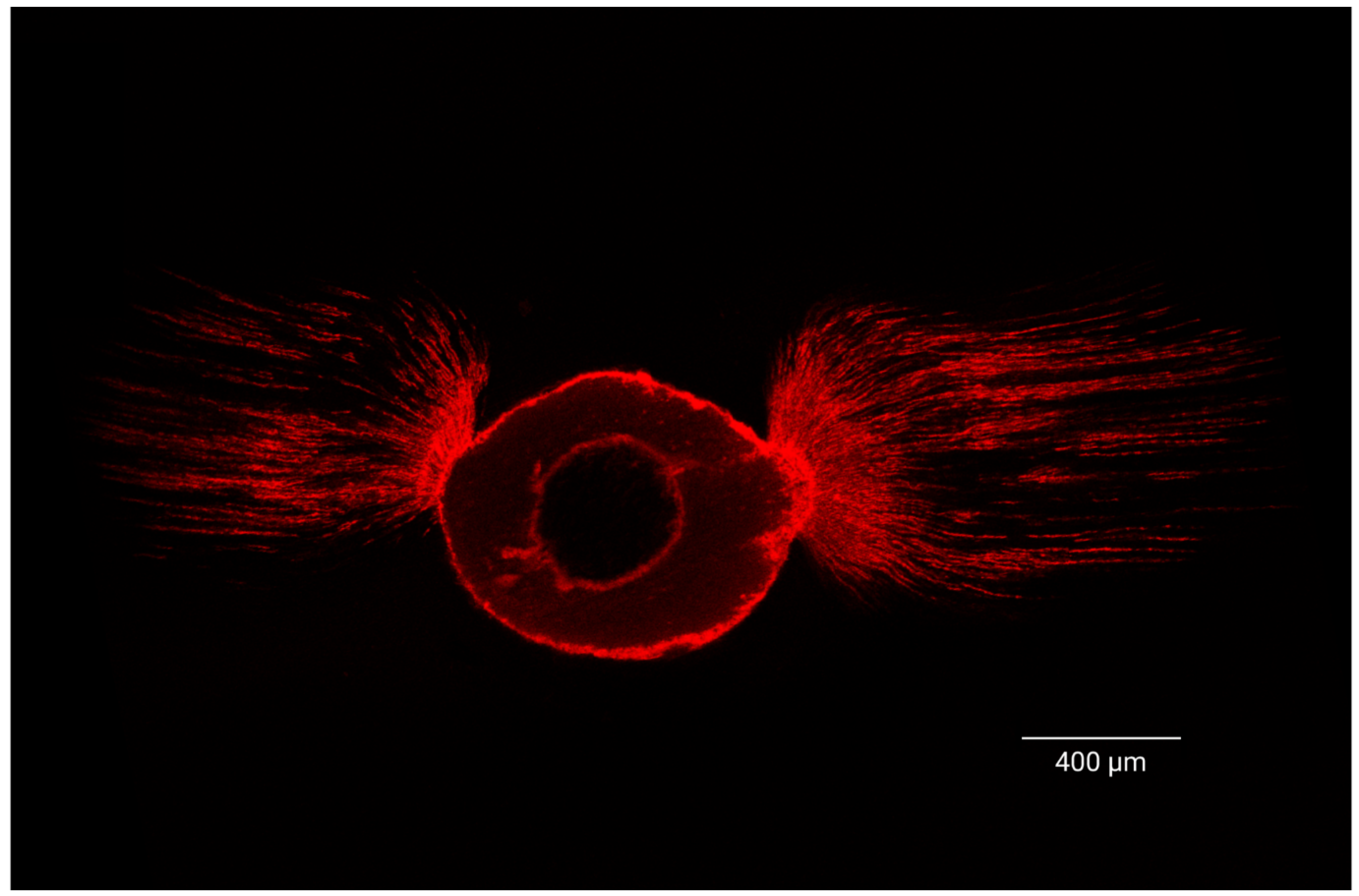

2.7. Confocal Laser Microscopy Morphometric Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

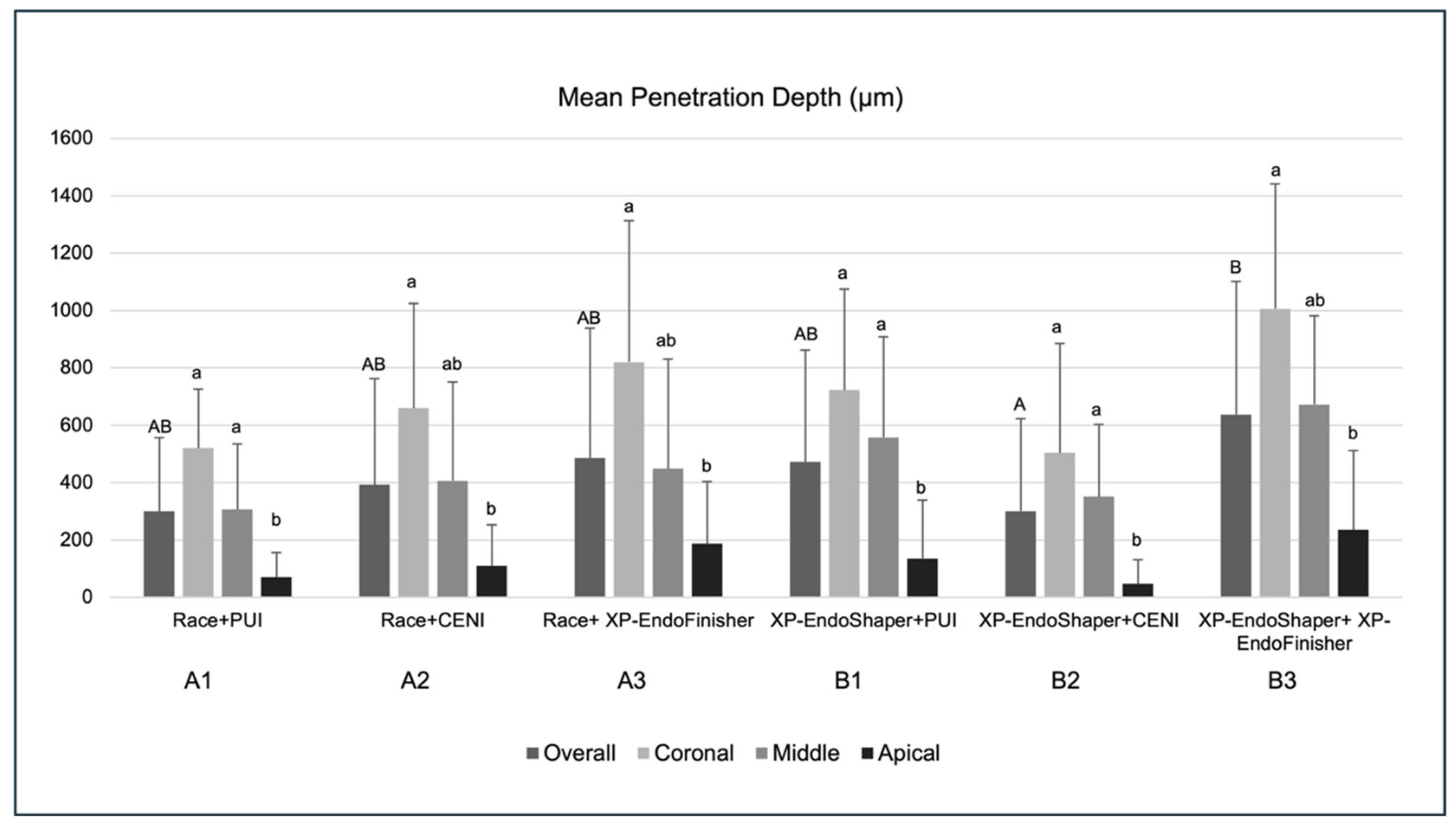

3.1. Mean Penetration Depth

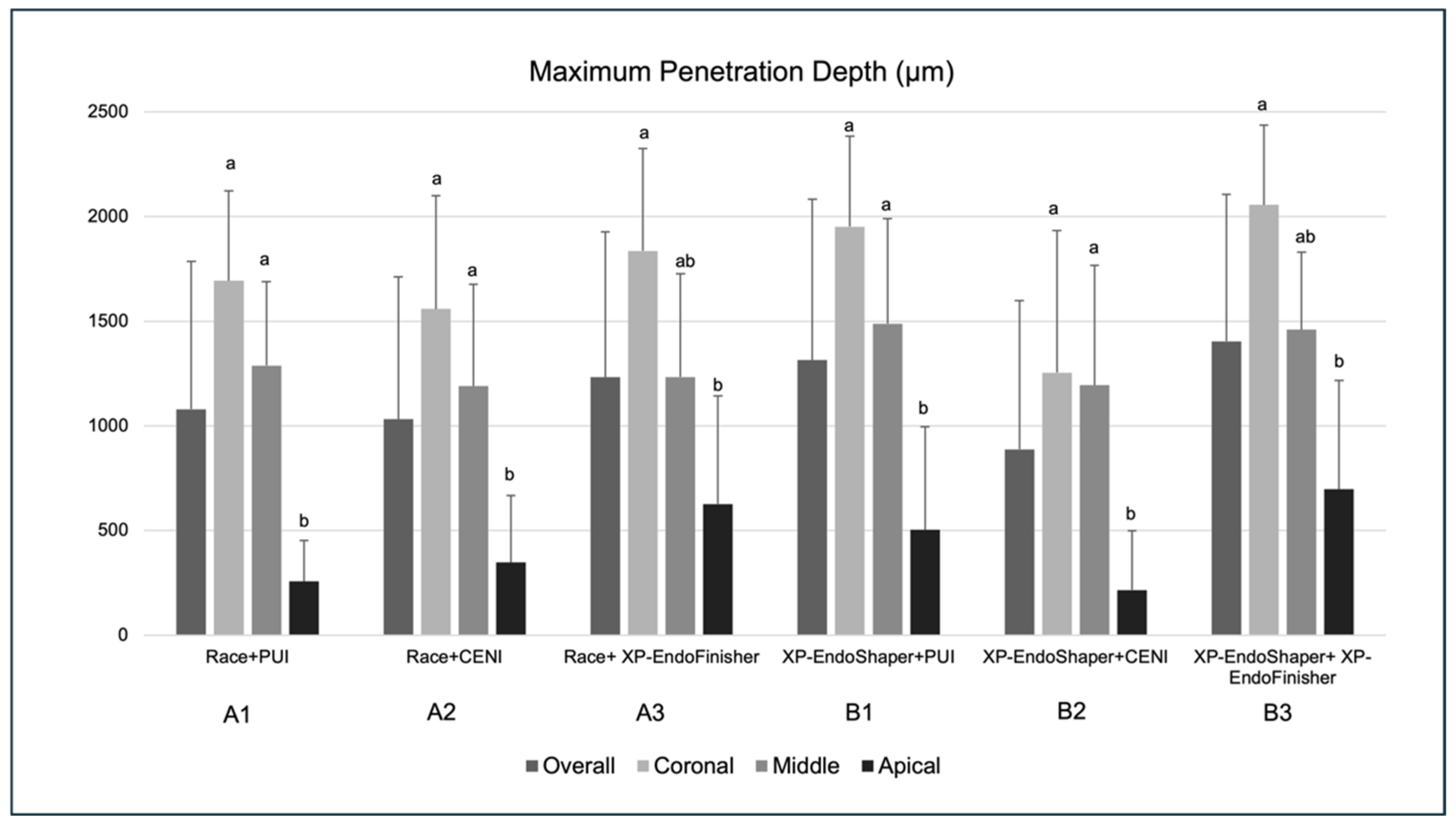

3.2. Maximum Penetration Depth

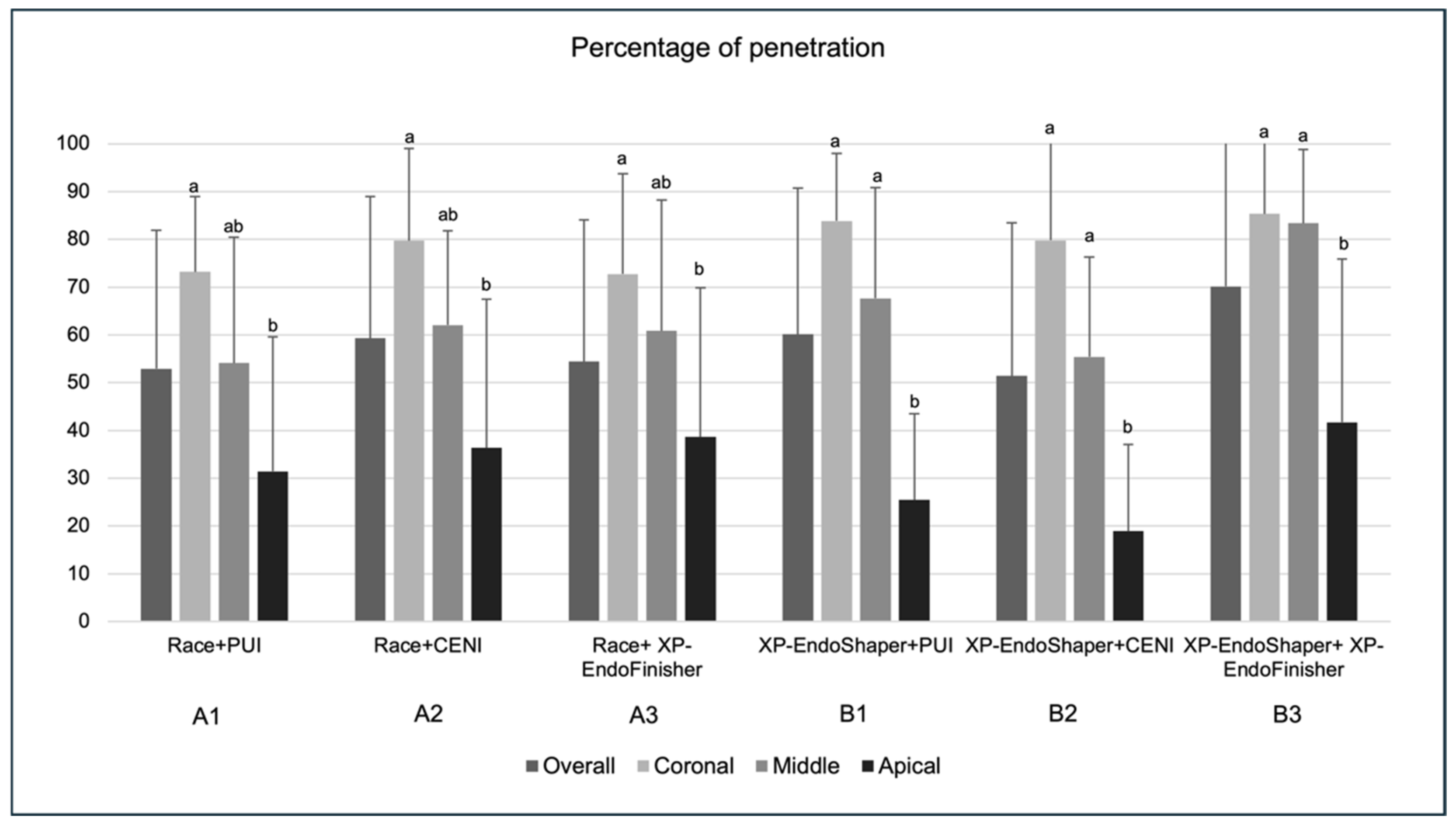

3.3. Mean Percentage of Sealer Penetration

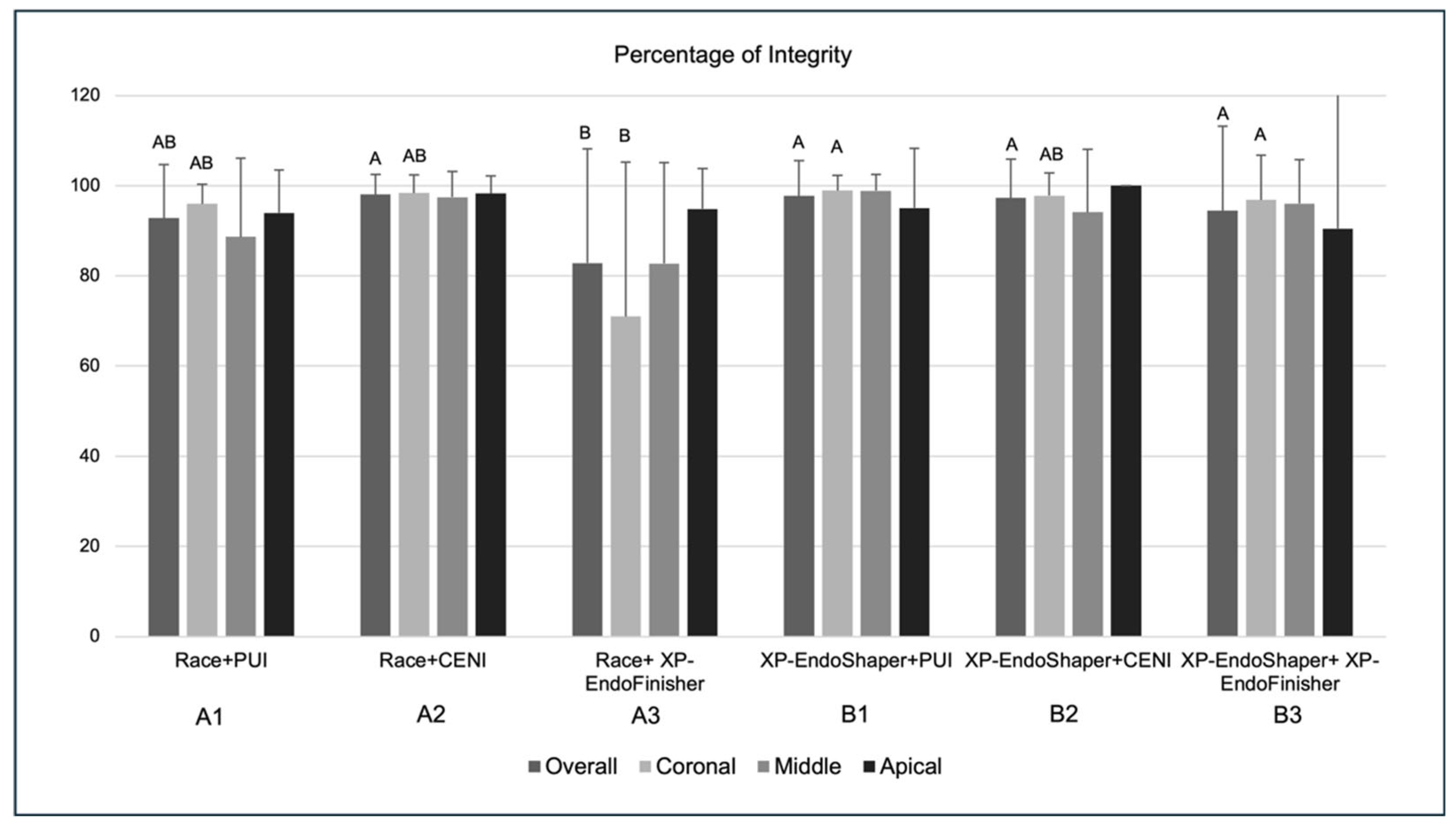

3.4. Percentage of Sealer Integrity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PUI | Passive ultrasonic irrigation |

| CENI | Conventional endodontic needle irrigation |

| PRILE | Preferred reporting items for laboratory studies in endodontology |

| CEJ | Cement–enamel junction |

| CLSM | Confocal laser scanning microscope |

References

- Raducka, M.; Piszko, A.; Piszko, P.J.; Jawor, N.; Dobrzyński, M.; Grzebieluch, W.; Mikulewicz, M.; Skośkiewicz-Malinowska, K. Narrative Review on Methods of Activating Irrigation Liquids for Root Canal Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilder, H. Cleaning and Shaping the Root Canal. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 1974, 18, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, Z.; Shalavi, S.; Yaripour, S.; Kinoshita, J.-I.; Manabe, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Giardino, L.; Palazzi, F.; Sharifi, F.; Jafarzadeh, H. Smear Layer Removing Ability of Root Canal Irrigation Solutions: A Review. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2019, 20, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Zheng, X.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Fan, B.; Liang, J.; Ling, J.; Bian, Z.; Yu, Q.; Hou, B.; et al. Expert Consensus on Irrigation and Intracanal Medication in Root Canal Therapy. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2024, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonini, R.; Salvadori, M.; Audino, E.; Sauro, S.; Garo, M.L.; Salgarello, S. Irrigating Solutions and Activation Methods Used in Clinical Endodontics: A Systematic Review. Front. Oral Health 2022, 3, 838043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, K.; Daniel, J.; Ahn, C.; Primus, C.; Komabayashi, T. Coronal and Apical Leakage among Five Endodontic Sealers. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 64, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.C.; Pinheiro, L.S.; Nunes, J.S.; de Almeida Mendes, R.; Schuster, C.D.; Soares, R.G.; Kopper, P.M.P.; de Figueiredo, J.A.P.; Grecca, F.S. Evaluation of the Biological and Physicochemical Properties of Calcium Silicate-Based and Epoxy Resin-Based Root Canal Sealers. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2022, 110, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeta, C.; Marruganti, C.; Mignosa, E.; Malvicini, G.; Verniani, G.; Tonini, R.; Grandini, S. Comparison of Physico-chemical Properties of Zinc Oxide Eugenol Cement and a Bioceramic Sealer. Aust. Endod. J. 2023, 49, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, Y.; Tulgar, M.M.; Karataslioglu, E.; Turk, T. Comparative Analysis of Dentinal Tubule Penetration: Effects of Irrigation Activation Methods and Root Canal Sealers: In-Vitro Study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generali, L.; Cavani, F.; Serena, V.; Pettenati, C.; Righi, E.; Bertoldi, C. Effect of Different Irrigation Systems on Sealer Penetration into Dentinal Tubules. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozasir, T.; Eren, B.; Gulsahi, K.; Ungor, M. The Effect of Different Final Irrigation Regimens on the Dentinal Tubule Penetration of Three Different Root Canal Sealers: A Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy Study In Vitro. Scanning 2021, 2021, 8726388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, G.E.; Primus, C.M.; Opperman, L.A. Dentinal Tubule Penetration of Tricalcium Silicate Sealers. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generali, L.; Prati, C.; Pirani, C.; Cavani, F.; Gatto, M.R.; Gandolfi, M.G. Double Dye Technique and Fluid Filtration Test to Evaluate Early Sealing Ability of an Endodontic Sealer. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakumaar, A.; Ganesh, A.; Kalaiselvam, R.; Rajan, M.; Deivanayagam, K. Evaluation of Debris and Smear Layer Removal with XP-Endo Finisher: A Scanning Electron Microscopic Study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2019, 30, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkahtany, S.M.; Alfadhel, R.; AlOmair, A.; Durayhim, S.B. Characteristics and Effectiveness of XP-Endo Files and Systems: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 2024, 9412427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velozo, C.; Albuquerque, D. Microcomputed Tomography Studies of the Effectiveness of XP-Endo Shaper in Root Canal Preparation: A Review of the Literature. Sci. World J. 2019, 2019, 3570870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, I.; Conde Villar, A.J.; Loroño, G.; Estevez, R.; Plotino, G.; Cisneros, R. Effectiveness of XP-Endo Finisher and Passive Ultrasonic Irrigation in the Removal of the Smear Layer Using Two Different Chelating Agents. J. Dent. 2021, 22, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, F.; Erdemir, A. Evaluating the Effect of Different Irrigation Activation Techniques on the Dentin Tubules Penetration of Two Different Root Canal Sealers by Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2023, 86, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, Ö.I.; Savur, I.G.; Alaçam, T.; Çelik, B. The Effectiveness of Various Irrigation Protocols on Organic Tissue Removal from Simulated Internal Resorption Defects. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balguerie, E.; Van Der Sluis, L.; Vallaeys, K.; Gurgel-Georgelin, M.; Diemer, F. Sealer Penetration and Adaptation in the Dentinal Tubules: A Scanning Electron Microscopic Study. J. Endod. 2011, 37, 1576–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, S.W. A Comparison of Canal Preparations in Straight and Curved Root Canals. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1971, 32, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvekar, P.S.; Shivanand, S.; Patil, S.; Raikar, S.; Mallick, A.; Doddwad, P.K. Dentinal Tubule Penetration of a Silicone-Based Endodontic Sealer Following N-Acetyl Cysteine Intracanal Medicament Removal Using Ultrasonic Agitation and Laser Activated Irrigation—An in Vitro Study. J. Conserv. Dent. Endod. 2025, 28, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardino, L.; Pedullà, E.; Cavani, F.; Bisciotti, F.; Giannetti, L.; Checchi, V.; Angerame, D.; Consolo, U.; Generali, L. Comparative Evaluation of the Penetration Depth into Dentinal Tubules of Three Endodontic Irrigants. Materials 2021, 14, 5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, K.V.; da Silva, B.M.; Leonardi, D.P.; Crozeta, B.M.; de Sousa-Neto, M.D.; Baratto-Filho, F.; Gabardo, M.C.L. Effectiveness of Different Final Irrigation Techniques and Placement of Endodontic Sealer into Dentinal Tubules. Braz. Oral. Res. 2017, 31, e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A.; Yalcin, T.Y.; Helvacioglu-Yigit, D. Effectiveness of Various Final Irrigation Techniques on Sealer Penetration in Curved Roots: A Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8060489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kermeoğlu, F.; Küçük, M. Efficacy of different irrigation methods on dentinal tubule penetration of Chlorhexidine, QMix and Irritrol: A confocal laser scanning microscopy study. Aust. Endod. J. 2019, 45, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara Tuncer, A.; Tuncer, S. Effect of Different Final Irrigation Solutions on Dentinal Tubule Penetration Depth and Percentage of Root Canal Sealer. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 860–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkol, E.; Özlek, E. Effectiveness of XP-Endo Finisher, Endoactivator, and PUI Agitation in the Penetration of Intracanal Medicaments into Dentinal Tubules: A Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope Analysis. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2024, 18, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, S.; Mallya, P.L.; Ballal, V.; Shenoy, R. To Evaluate and Compare the Effect of 17% EDTA, 10% Citric Acid, 7% Maleic Acid on the Dentinal Tubule Penetration Depth of Bio Ceramic Root Canal Sealer Using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy: An in Vitro Study. F1000Research 2022, 11, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjör, I.A.; Smith, M.R.; Ferrari, M.; Mannocci, F. The Structure of Dentine in the Apical Region of Human Teeth. Int. Endod. J. 2001, 34, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktemur Türker, S.; Uzunoğlu, E.; Purali, N. Evaluation of Dentinal Tubule Penetration Depth and Push-out Bond Strength of AH 26, BioRoot RCS, and MTA Plus Root Canal Sealers in Presence or Absence of Smear Layer. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2018, 12, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikatla, S.K.; Chalasani, U.; Mandava, J.; Yelisela, R.K. Interfacial Adaptation and Penetration Depth of Bioceramic Endodontic Sealers. J. Conserv. Dent. 2018, 21, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachem, R.; Khalil, I.; Le Brun, G.; Pellen, F.; Le Jeune, B.; Daou, M.; El Osta, N.; Naaman, A.; Abboud, M. Dentinal Tubule Penetration of AH Plus, BC Sealer and a Novel Tricalcium Silicate Sealer: A Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy Study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 1871–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eymirli, A.; Sungur, D.D.; Uyanik, O.; Purali, N.; Nagas, E.; Cehreli, Z.C. Dentinal Tubule Penetration and Retreatability of a Calcium Silicate-Based Sealer Tested in Bulk or with Different Main Core Material. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 1036–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, B.-S.; Kim, Y.-M.; Lee, D.; Kim, S.-Y. The Penetration Ability of Calcium Silicate Root Canal Sealers into Dentinal Tubules Compared to Conventional Resin-Based Sealer: A Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy Study. Materials 2019, 12, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, A.; Friedlander, L.; Chandler, N. Sealer Penetration and Adaptation in Root Canals with the Butterfly Effect. Aust. Endod. J. 2018, 44, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, A.A.; Chandler, N.P.; Hauman, C.; Siddiqui, A.Y.; Tompkins, G.R. The Butterfly Effect: An Investigation of Sectioned Roots. J. Endod. 2013, 39, 208–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrigan, P.J.; Morse, D.R.; Furst, M.L.; Sinai, I.H. A Scanning Electron Microscopic Evaluation of Human Dentinal Tubules According to Age and Location. J. Endod. 1984, 10, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, M.; Yang, X.; Yang, J. Evaluating the Penetration, Interfacial Adaptation, and Push-out Bond Strength of Four Bioceramic-Based Root Canal Sealers. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataşlioğlu, E.; Tosun, S. Effect of Different Sealer Placement and Activation Techniques on Sealer Penetration Depth and Penetration Area. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2025, 88, 2878–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnermeyer, D.; Schmidt, S.; Rohrbach, A.; Berlandi, J.; Bürklein, S.; Schäfer, E. Debunking the Concept of Dentinal Tubule Penetration of Endodontic Sealers: Sealer Staining with Rhodamine B Fluorescent Dye Is an Inadequate Method. Materials 2021, 14, 3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathi, A.; Chowdhry, P.; Kaushik, M.; Reddy, P.; Roshni, R.; Mehra, N. Effect of Different Periodontal Ligament Simulating Materials on the Incidence of Dentinal Cracks during Root Canal Preparation. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2018, 12, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Working Length and Glide Path | Groups Based on Different Chemo-Mechanical Shaping Protocols | Shaping Protocols | Irrigant Activation Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-file #10 at WL 2 mL NaOCl 5.25% Endowave MGP 10/.02 * 2 mL NaOCL 5.25% Endowave MGP 15/.02 * 2 mL NaOCL 5.25% Endowave MGP 20/.02 * 2 mL NaOCL 5.25% * 800 rpm, 0.4 N/cm torque | (A1) Race + PUI; (A2) Race + CENI; (A3) Race + XP-Endo Finisher; (B1) XP-Endo Shaper + PUI; (B2) XP-Endo Shaper + CENI; (B3) XP-Endo Shaper + XP-Endo Finisher | (A) Race Race 20/.04 * 2 mL NaOCl 5.25% Race 25/.04 * 2 mL NaOCl 5.25% Race 30/.04 * * 600 rpm, 1.5 N/cm torque (B) XP-Endo Shaper Xp-Endo Shaper * 3/5× to reach WL, immersed in NaOCl 5.25% 2 mL NaOCl 5.25% Xp-Endo Shaper * 15× to WL, immersed in NaOCl 5.25% * 1000 rpm, 1 N/cm torque | (1) PUI (EndoUltra) 1 mL NaOCl 5.25% ultrasound-activated 30 s 1 mL NaOCl 5.25% ultrasound-activated 30 s 1 mL EDTA 17% ultrasound-activated 30 s 1 mL EDTA 17% ultrasound-activated 30 s 2 mL saline |

| (2) CENI 1 mL NaOCl 5.25% with side-vented needle at WL-2 mm, 30 s 1 mL NaOCl 5.25% with side-vented needle at WL-2 mm, 30 s 1 mL EDTA 17% with side-vented needle at WL-2 mm, 30 s 1 mL EDTA 17% with side-vented needle at WL-2 mm, 30 s 2 mL saline | |||

| (3) XP-Endo Finisher 2 mL NaOCl 5.25% activated with XP-Endo Finisher *, 60 s 2 mL EDTA 17% activated with XP-Endo Finisher *, 60 s 2 mL saline * 1000 rpm and 1 N/cm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Generali, L.; Veneri, F.; Gaeta, C.; Cavani, F.; Ambu, E.; Bertucci, S.; Vallotto, G.; Filippini, T.; Pedullà, E. Effect of Different Chemo-Mechanical Shaping Protocols on the Intratubular Penetration of a Bioceramic Sealer. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031132

Generali L, Veneri F, Gaeta C, Cavani F, Ambu E, Bertucci S, Vallotto G, Filippini T, Pedullà E. Effect of Different Chemo-Mechanical Shaping Protocols on the Intratubular Penetration of a Bioceramic Sealer. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031132

Chicago/Turabian StyleGenerali, Luigi, Federica Veneri, Carlo Gaeta, Francesco Cavani, Emanuele Ambu, Sara Bertucci, Giuseppina Vallotto, Tommaso Filippini, and Eugenio Pedullà. 2026. "Effect of Different Chemo-Mechanical Shaping Protocols on the Intratubular Penetration of a Bioceramic Sealer" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031132

APA StyleGenerali, L., Veneri, F., Gaeta, C., Cavani, F., Ambu, E., Bertucci, S., Vallotto, G., Filippini, T., & Pedullà, E. (2026). Effect of Different Chemo-Mechanical Shaping Protocols on the Intratubular Penetration of a Bioceramic Sealer. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031132