Real-World Utilization of Midostaurin in Combination with Intensive Chemotherapy for Patients with FLT3 Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Multicenter Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Study Design

2.2. Treatment Protocol

2.3. Study Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Döhner, H.; Weisdorf, D.J.; Bloomfield, C.D. Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1136–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, F.; Lessi, F.; Vitagliano, O.; Birkenghi, E.; Rossi, G. Current Therapeutic Results and Treatment Options for Older Patients with Relapsed Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers 2019, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.H.; Lee, H.; Won, Y.J.; Ju, H.Y.; Oh, C.M.; Ingabire, C.; Kong, H.J.; Park, B.K.; Yoon, J.Y.; Eom, H.S.; et al. Nationwide statistical analysis of myeloid malignancies in Korea: Incidence and survival rate from 1999 to 2012. Blood Res. 2015, 50, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafone, T.; Palmisano, M.; Nicci, C.; Storti, S. An overview on the role of FLT3-tyrosine kinase receptor in acute myeloid leukemia: Biology and treatment. Oncol. Rev. 2012, 6, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daver, N.; Schlenk, R.F.; Russell, N.H.; Levis, M.J. Targeting FLT3 mutations in AML: Review of current knowledge and evidence. Leukemia 2019, 33, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, R.A.; Mandrekar, S.J.; Huebner, L.J.; Sanford, B.L.; Laumann, K.; Geyer, S.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Thiede, C.; Prior, T.W.; Döhner, K.; et al. Midostaurin reduces relapse in FLT3-mutant acute myeloid leukemia: The Alliance CALGB 10603/RATIFY trial. Leukemia 2021, 35, 2539–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, N.J.; Rytting, M.E.; Cortes, J.E. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet 2018, 392, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, R.M.; Mandrekar, S.J.; Sanford, B.L.; Laumann, K.; Geyer, S.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Thiede, C.; Prior, T.W.; Döhner, K.; Marcucci, G.; et al. Midostaurin plus Chemotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia with a FLT3 Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.M.; Mandrekar, S.J.; Sanford, B.L.; Laumann, K.; Geyer, S.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Dohner, K.; Thiede, C.; Marcucci, G.; Lo-Coco, F.; et al. The Addition of Midostaurin to Standard Chemotherapy Decreases Cumulative Incidence of Relapse (CIR) in the International Prospective Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial (CALGB 10603/RATIFY [Alliance]) for Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Patients with FLT3 Mutations. Blood 2017, 130, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.M.; Manley, P.W.; Larson, R.A.; Capdeville, R. Midostaurin: Its odyssey from discovery to approval for treating acute myeloid leukemia and advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 444–453, Erratum in Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 787. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018018481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhner, H.; Weber, D.; Krzykalla, J.; Fiedler, W.; Wulf, G.; Salih, H.; Lübbert, M.; Kühn, M.W.M.; Schroeder, T.; Salwender, H.; et al. Midostaurin plus intensive chemotherapy for younger and older patients with AML and FLT3 internal tandem duplications. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 5345–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0, The National Cancer Institute (NCI): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2009.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Rydapt (Midostaurin): EPAR—Product Information. 2018. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/rydapt-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Requena, G.A.; Dumas, P.Y.; Rodriguez Veiga, R.; Bertoli, S.; Gil, C.; Simand, C.; Ramos-Ortega, F.J.; Peterlin, P.; Serrano, J.; Birsen, R.; et al. Real-world outcomes using front-line midostaurine in combination with intensive chemotherapy for patients aged ≥60 years with FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2023, 142, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzell, B.G.; Marini, B.L.; Benitez, L.L.; Bixby, D.; Burke, P.; Pettit, K.; Perissinotti, A.J. Real world use of FLT3 inhibitors for treatment of FLT3+ acute myeloid leukemia (AML): A single center, propensity-score matched, retrospective cohort study. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 28, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.; Rozovski, U.; Moshe, Y.; Yaari, S.; Frisch, A.; Hellmann, I.; Apel, A.; Aviram, A.; Koren-Michowitz, M.; Yeshurun, M.; et al. Midostaurin in combination with intensive chemotherapy is safe and associated with improved remission rates and higher transplantation rates in first remission-a multi-center historical control study. Ann. Hematol. 2019, 98, 2711–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Wagner, C.B.; Prelewicz, S.; Kurish, H.P.; Walchack, R.; Cenin, D.A.; Patel, S.; Lo, M.; Schlafer, D.; Li, B.K.T.; et al. Efficacy and toxicity of midostaurin with idarubicin and cytarabine induction in FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2023, 108, 3460–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, M.; Piciocchi, A.; Siena, L.M.; Soddu, S.; Buccisano, F.; Mecucci, C.; Martinelli, G.; Curti, A.; Cairoli, R.; Fazi, P.; et al. A GIMEMA survey on therapeutic use and response rates of FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia: Insights from Italian real-world practice. EJHaem 2024, 5, 1274–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Peng, M.; Qian, Y.; Wu, F.; Rao, Q.; DanZhen, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. A disproportionality analysis for assessing the safety of FLT3 inhibitors using the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2024, 15, 20420986241284105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzogani, K.; Yu, Y.; Meulendijks, D.; Herberts, C.; Hennik, P.; Verheijen, R.; Wangen, T.; Dahlseng Håkonsen, G.; Kaasboll, T.; Dalhus, M.; et al. European Medicines Agency review of midostaurin (Rydapt) for the treatment of adult patients with acute myeloid leukaemia and systemic mastocytosis. ESMO Open 2019, 4, e000606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeZern, A.E.; Sung, A.; Kim, S.; Smith, B.D.; Karp, J.E.; Gore, S.D.; Jones, R.J.; Fuchs, E.; Luznik, L.; McDevitt, M.; et al. Role of allogeneic transplantation for FLT3/ITD acute myeloid leukemia: Outcomes from 133 consecutive newly diagnosed patients from a single institution. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 2011, 17, 1404–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhner, K.; Thiede, C.; Larson, R.A.; Prior, T.W.; Marcucci, G.; Jones, D.; Krauter, J.; Heuser, M.; Lo Coco, F.; Ottone, T.; et al. Prognostic impact of NPM1/FLT3-ITD genotypes from randomized patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated within the international RATIFY study. Blood 2017, 130, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Gender, | n (%) |

| Female | 28 (49.1) |

| Male | 29 (50.9) |

| Age at AML diagnosis, years (range) | 5 (20–70) |

| ≥60 years old at AML diagnosis | 18 (31.5) |

| ECOG | |

| 0 | 16 (28.1) |

| 1 | 28 (49.1) |

| 2 | 13 (22.8) |

| Comorbidities | |

| DM | 8 (14) |

| HT | 20 (35.1) |

| CKD | 5 (8.8) |

| COPD | 6 (10.5) |

| CAD | 6 (10.5) |

| Breast cancer | 1 (1.8) |

| Hypothyroidism | 3 (5.3) |

| Disease characteristics | |

| 2017 ELN risk stratification by genetics | n (%) |

| Favourable | 2 (3.5) |

| Intermediate | 23(40.3) |

| Adverse | 32 (56.1) |

| Karyotype, n (%) | |

| Normal karyotype | 47 (82.5) |

| Abnormal karyotype | 10 (17.5) |

| Subtype of FLT3 mutation—n (%) | |

| ITD | 48 (84.2) |

| TKD | 7 (12.3) |

| Both | 2 (3.5) |

| NPM1 mutated, n (%) | 12 (21.1) |

| Leukemia, n (%) | |

| De novo | 49 (86) |

| Secondary | 8 (14) |

| Clinical and laboratory characteristics at presentation | |

| Median white blood count per μL (range) | 43,990 (340–361,850) |

| Median platelet count per μL (range) | 56,000 (6000–191,000) |

| Median hemoglobin level (range) (g/dL) | 8 (5–13) |

| Median % marrow blasts | 80 (20–98) |

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients that received consolidation chemotherapy | 50 (87.7) |

| Median number (range) of consolidation cycles | 3 (0–4) |

| HSC transplantation | 31 (54.4) |

| HSC transplantation in CR1 | 30 (52.6) |

| Midostaurin treatment | |

| During induction | |

| Number of patients with stopped treatment | 1 (1.7) |

| Number of patients with dose reduction/interruption | 2 (3.5) |

| During consolidation | |

| Number of patients with stopped treatment | 1 (1.7) |

| Number of patients with dose reduction/interruption | 2 (3.5) |

| Outcome | Definition | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

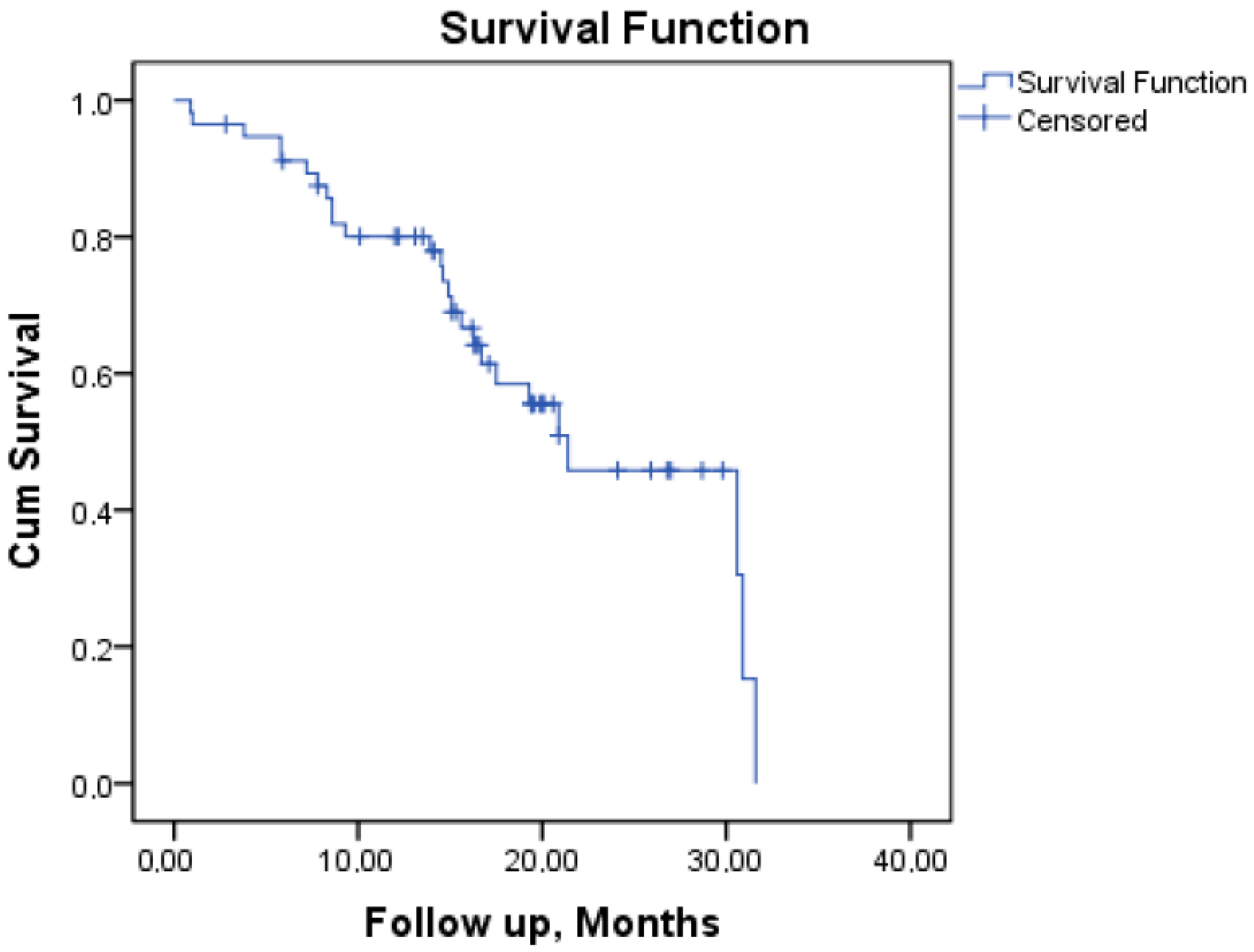

| OS | Alive | 31 (54.4) |

| Dead | 26 (45.6) | |

| Median OS (months) | 21.4 | |

| Allogeneic HSCT | HSCT received | 31 (54.4) |

| Time to HSCT (months) | 4.2 (2–16.4) | |

| ORR rate | ||

| CR | 48 (84.2) | |

| Cri | 2 (3.5) | |

| Refractory | 5 (8.8) | |

| Induction death | 2 (3.5) |

| Variables | Any Grade | Grades 3–4 |

|---|---|---|

| Hematological adverse events, n (%) | ||

| Neutropenic fever episodes, n (%) | 47 (82.5) | 47 (82.5) |

| Leukopenia | 51 (89.4) | 44 (77.1) |

| Neutropenia | 53 (92.9) | 46 (80.7) |

| Lymphopenia | 50 (87.7) | 41 (71.9) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 52 (91.2) | 48 (84.2) |

| Anemia | 53 (92.9) | 39 (68.4) |

| Non-hematological adverse events, n (%) | ||

| Rash | 14 (24.5) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal toxicity | ||

| Diarrhea | 21 (36.8) | 3 (5.2) |

| Nausea | 56 (98.2) | 8 (14) |

| Vomiting | 50 (87.7) | 3 (5.2) |

| Constipation | 24 (42.1) | 0 |

| Hepatic toxicity | ||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 15 (26.3) | 1 (1.7) |

| Increased alanine aminotransferase | 19 (33.3) | 2 (3.5) |

| Increased aspartate aminotransferase | 15 (26.3) | 0 |

| Renal toxicity | ||

| Hypokalemia | 39 (68.4) | 15 (26.3) |

| Hyponatremia | 13 (22.8) | 1 (1.7) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 14 (24.5) | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 19 (33.3) | 3 (5.2) |

| Infection | ||

| Pneumonitis or pulmonary infiltrates | 25 (43.8) | |

| Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) | 2 (3.5) | |

| Rectitis | 7 (12.2) | |

| Sepsis or septic shock | 4 (7) | |

| Other infections | 15 (26.3) | |

| Pain | 29 (50.8) | 2 (3.5) |

| Fatigue | 54 (94.7) | 6 (10.5) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (1.7) | |

| QT prolongation | 1 (1.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Seçilmiş, S.; Kabukçu Hacıoğlu, S.; Hindilerden, F.; Turgut, B.; Özatlı, D.; Akgün Çağlıyan, G.; Baştürk, A.; Yüksel Öztürkmen, A.; Katırcılar, Y.; Namdaroğlu, S.; et al. Real-World Utilization of Midostaurin in Combination with Intensive Chemotherapy for Patients with FLT3 Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020854

Seçilmiş S, Kabukçu Hacıoğlu S, Hindilerden F, Turgut B, Özatlı D, Akgün Çağlıyan G, Baştürk A, Yüksel Öztürkmen A, Katırcılar Y, Namdaroğlu S, et al. Real-World Utilization of Midostaurin in Combination with Intensive Chemotherapy for Patients with FLT3 Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):854. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020854

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeçilmiş, Sema, Sibel Kabukçu Hacıoğlu, Fehmi Hindilerden, Burhan Turgut, Düzgün Özatlı, Gülsüm Akgün Çağlıyan, Abdulkadir Baştürk, Aslı Yüksel Öztürkmen, Yavuz Katırcılar, Sinem Namdaroğlu, and et al. 2026. "Real-World Utilization of Midostaurin in Combination with Intensive Chemotherapy for Patients with FLT3 Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Multicenter Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020854

APA StyleSeçilmiş, S., Kabukçu Hacıoğlu, S., Hindilerden, F., Turgut, B., Özatlı, D., Akgün Çağlıyan, G., Baştürk, A., Yüksel Öztürkmen, A., Katırcılar, Y., Namdaroğlu, S., Ünver Koluman, B., Sunu, C., Korkmaz, S., Uysal, A., Bilen, Y., Erkurt, M. A., Dal, M. S., Ulaş, T., & Altuntaş, F. (2026). Real-World Utilization of Midostaurin in Combination with Intensive Chemotherapy for Patients with FLT3 Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020854