Impact of COVID-19 on Respiratory Function: A Post-Recovery Comparative Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

- Age ≥ 18 years

- Confirmed diagnosis of post-COVID-19 syndrome

- Availability for pulmonary function testing

- Signed informed consent

- Age < 18 years

- Absence of informed consent

- Pregnancy or breastfeeding

- Bronchial asthma

- Interstitial lung diseases (including sarcoidosis and pulmonary fibrosis)

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Bronchiectasis

- Active respiratory infection within 4–6 weeks prior to assessment

- Active or recent pulmonary malignancy

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Pulmonary Function Testing

2.4. Patient Grouping Based on Time Since Infection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethics Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Baseline Characteristics

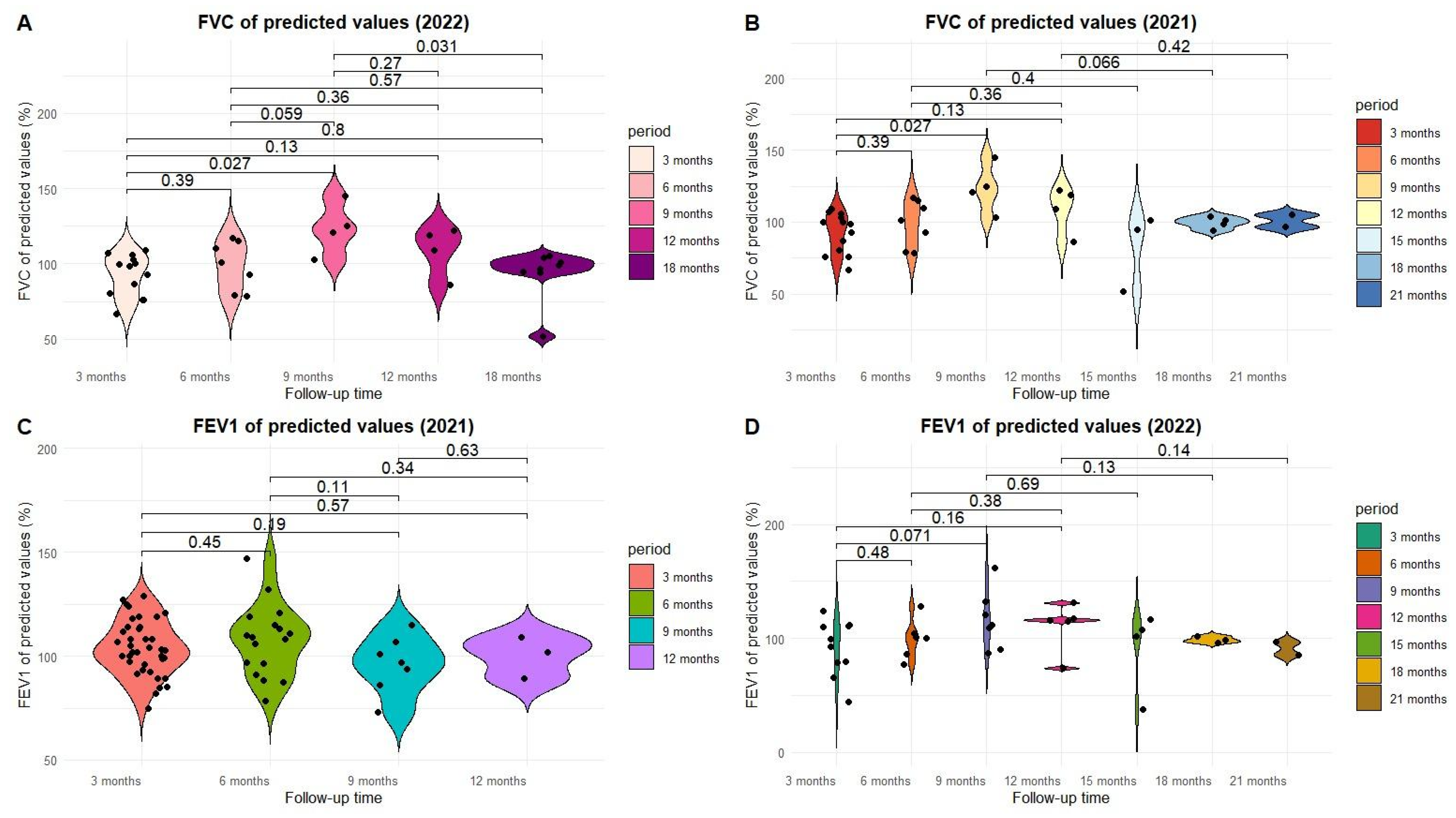

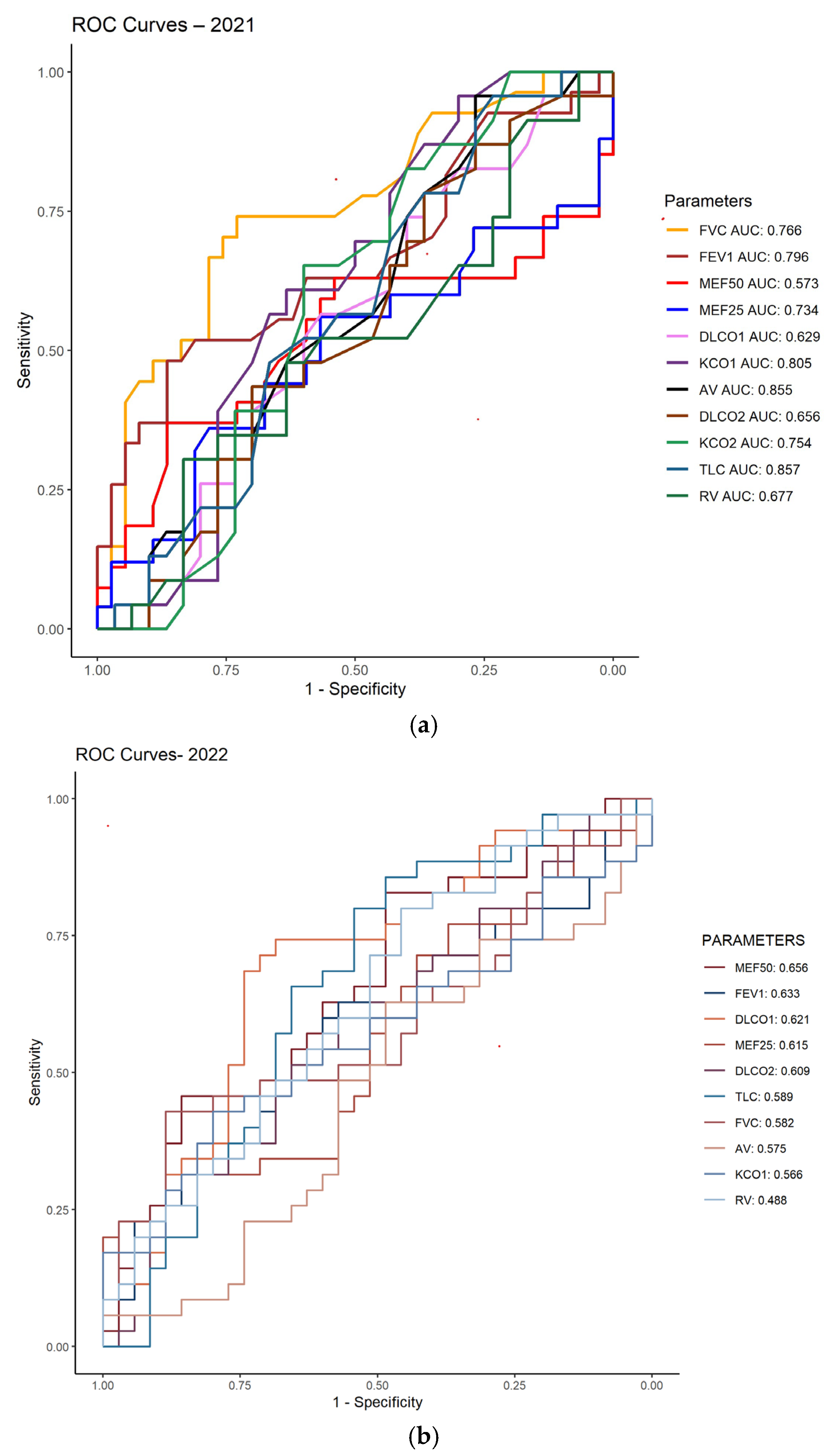

3.2. ROC Analysis of Pulmonary Function in Post-COVID-19 Patients (2021–2022)

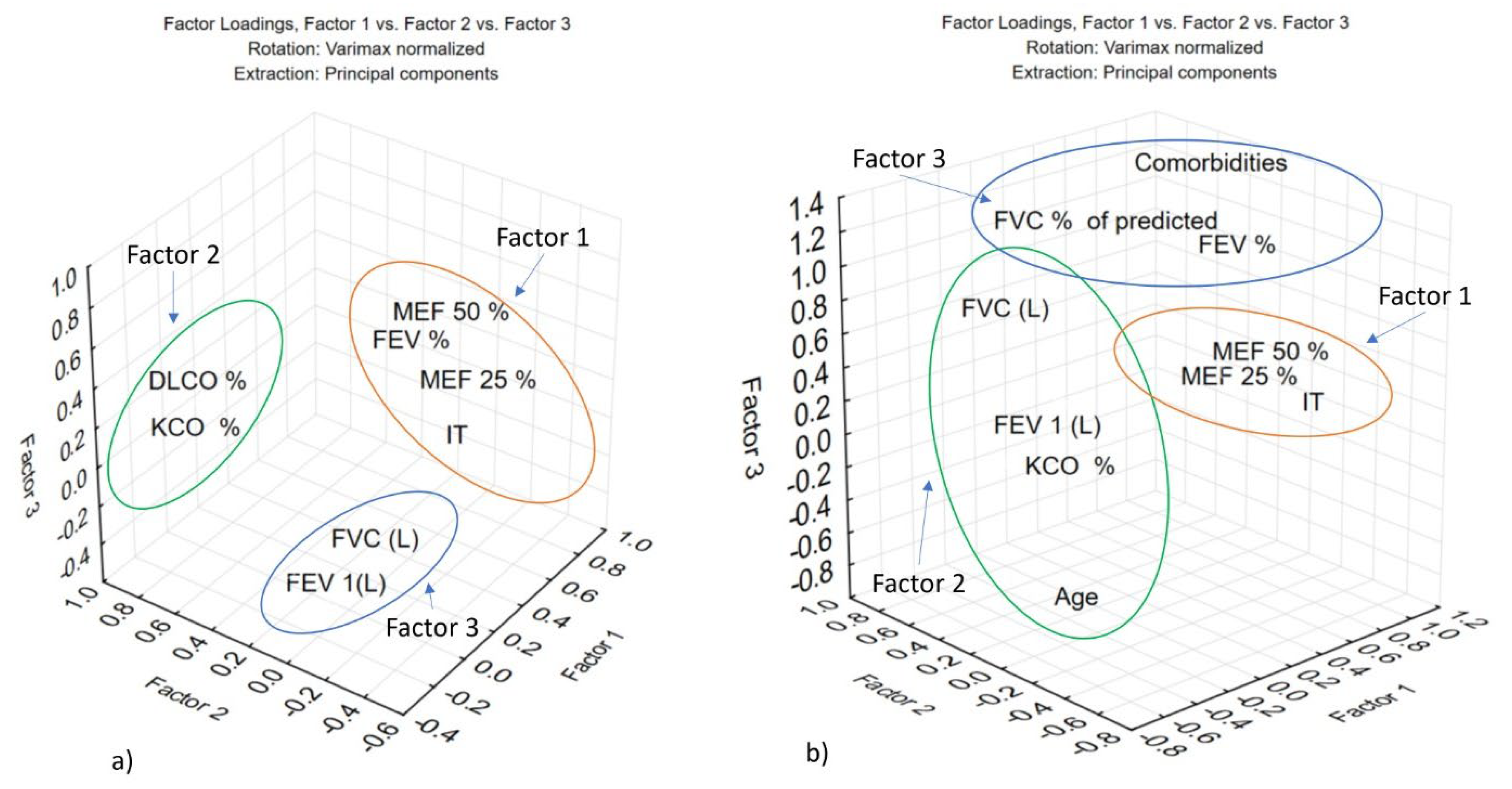

3.3. Characterization of Pulmonary Function in Post-COVID-19 Patients (2021–2022) Using Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Florencio, L.L. Defining Post-COVID Symptoms (Post-Acute COVID, Long COVID, Persistent Post-COVID): An Integrative Classification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Cases | WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Long, B.; Carius, B.M.; Chavez, S.; Liang, S.Y.; Brady, W.J.; Koyfman, A.; Gottlieb, M. Clinical Update on COVID-19 for the Emergency Clinician: Presentation and Evaluation. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 54, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baj, J.; Karakuła-Juchnowicz, H.; Teresiński, G.; Buszewicz, G.; Ciesielka, M.; Sitarz, R.; Forma, A.; Karakuła, K.; Flieger, W.; Portincasa, P.; et al. COVID-19: Specific and Non-Specific Clinical Manifestations and Symptoms: The Current State of Knowledge. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Henry, B.M. COVID-19 and Its Long-Term Sequelae: What Do We Know in 2023? Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2023, 133, 16402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, P.M.; Barratt, S.L.; Condliffe, R.; Desai, S.R.; Devaraj, A.; Forrest, I.; Gibbons, M.A.; Hart, N.; Jenkins, R.G.; McAuley, D.F.; et al. Respiratory Follow-Up of Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia. Thorax 2020, 75, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasserie, T.; Hittle, M.; Goodman, S.N. Assessment of the Frequency and Variety of Persistent Symptoms Among Patients With COVID-19: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2111417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/post-covid-19-condition-(long-covid) (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Zhao, Y.; Shang, Y.; Song, W.; Li, Q.; Xie, H.; Xu, Q.; Jia, J.; Li, L.; Mao, H.; Zhou, X.; et al. Follow-Up Study of the Pulmonary Function and Related Physiological Characteristics of COVID-19 Survivors Three Months after Recovery. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 25, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofor, A.; Robu Popa, D.; Melinte, O.; Trofor, L.; Vicol, C.; Grosu-Creangă, I.; Crișan Dabija, R.; Cernomaz, A. Looking at the Data on Smoking and Post-COVID-19 Syndrome—A Literature Review. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dong, X.; Liu, G.; Gao, Y. Risk and Protective Factors for COVID-19 Morbidity, Se-verity, and Mortality. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 64, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñalvo, J.L.; Mertens, E.; Ademović, E.; Akgun, S.; Baltazar, A.L.; Buonfrate, D.; Čoklo, M.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Diaz Valencia, P.A.; Fernandes, J.C.; et al. Unravelling Data for Rapid Evidence-Based Response to COVID-19: A Summary of the unCoVer Protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e055630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, S.; Reddy, S.; Gholamrezanezhad, A. Long-Term Pulmonary Consequences of Corona-virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): What We Know and What to Expect. J. Thorac. Imaging 2020, 35, W87–W89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Zhang, L.; Ni-jia-Ti, M.; Zhang, J.; Hu, F.; Chen, L.; Dong, Y.; Yang, K.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S. Anormal Pulmonary Function and Residual CT Abnormalities in Rehabilitating COVID-19 Patients after Discharge. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e150–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suppini, N.; Fira-Mladinescu, O.; Traila, D.; Motofelea, A.C.; Marc, M.S.; Manolescu, D.; Vastag, E.; Maganti, R.K.; Oancea, C. Longitudinal Analysis of Pulmonary Function Impairment One Year Post-COVID-19: A Single-Center Study. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Q.; Li, J.; Hu, X.; Bai, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, Z. Follow-Ups on Persistent Symptoms and Pulmonary Function Among Post-Acute COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Me-ta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 702635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, T.; Van Den Heuvel, J.; Van Kampen-van Den Boogaart, V.; Van Zeeland, R.; Me-hagnoul-Schipper, D.J.; Barten, D.G.; Knarren, L.; Maas, A.F.G.; Wyers, C.E.; Gach, D.; et al. Pulmonary Function Three to Five Months after Hospital Discharge for COVID-19: A Single Centre Cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Telles, A.; López-Romero, S.; Figueroa-Hurtado, E.; Pou-Aguilar, Y.N.; Wong, A.W.; Milne, K.M.; Ryerson, C.J.; Guenette, J.A. Pulmonary Function and Functional Capacity in COVID-19 Survivors with Persistent Dyspnoea. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2021, 288, 103644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennella, S.; Alicino, C.; Anselmo, M.; Carrega, G.; Ficarra, G.; Garra, L.; Gastaldo, A.; Gnerre, P.; Lillo, F.; Tassara, R.; et al. COVID-19 after 2 Years from Hospital Discharge: A Pulmonary Function and Chest Computed Tomography Follow-Up Study. Respiration 2024, 103, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Deng, J.; Liu, Q.; Du, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Long-Term Consequences of COVID-19 at 6 Months and Above: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peach, B.C.; Valenti, M.; Sole, M.L. A Call for the World Health Organization to Create Inter-national Classification of Disease Diagnostic Codes for Post-Intensive Care Syndrome in the Age of COVID-19. World Med. Health Policy 2021, 13, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.L.; Steenbruggen, I.; Miller, M.R.; Barjaktarevic, I.Z.; Cooper, B.G.; Hall, G.L.; Hall-strand, T.S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; McCarthy, K.; McCormack, M.C.; et al. Standardization of Spirometry 2019 Update. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Technical Statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e70–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Huang, L.; Gu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Lung-Function Trajectories in COVID-19 Survivors after Discharge: A Two-Year Longitudinal Cohort Study. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 54, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, M.; Kabata, H.; Fukunaga, K.; Takagi, H.; Kuno, T. Radiological and Functional Lung Sequelae of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; Miller, M.R.; Thompson, B.; Aliverti, A.; Barjaktarevic, I.; Cooper, B.G.; Culver, B.; Derom, E.; Hall, G.L.; et al. ERS/ATS Technical Standard on Interpretive Strategies for Routine Lung Function Tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Trujillo, L.; Galindo-Sánchez, J.S.; Cediel, A.; García, C.A.; Morales, E.I.; Largo, J.; Amezquita-Dussan, M.A. Six and Twelve-Month Respiratory Outcomes in a Cohort of Severe and Critical COVID-19 Survivors: A Prospective Monocentric Study in Latin America. SAGE Open Med. 2024, 12, 20503121241275369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Price, O.J.; Hull, J.H. Pulmonary Function and COVID-19. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 21, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Yim, J.-J.; Park, J. Pulmonary Function and Chest Computed Tomography Abnormalities 6–12 Months after Recovery from COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sárközi, A.T.; Tornyi, I.; Békési, E.; Horváth, I. Co-Morbidity Clusters in Post-COVID-19 Syn-drome. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, D.R.; Arcana, R.I.; Dabija, R.A.C.; Zabara, A.; Zabara, M.L.; Cernomaz, A.; Melinte, O.; Trofor, A. Lung Function Assessment Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Past, Present and Future? Pneumologia 2022, 71, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, E.; Díaz-García, E.; García-Tovar, S.; Galera, R.; Casitas, R.; Torres-Vargas, M.; López-Fernández, C.; Añón, J.M.; García-Río, F.; Cubillos-Zapata, C. Endothelial Dysfunction and Persistent Inflammation in Severe Post-COVID-19 Patients: Implications for Gas Exchange. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towe, C.W.; Badrinathan, A.; Khil, A.; Alvarado, C.E.; Ho, V.P.; Bassiri, A.; Linden, P.A. Non-Traditional Pulmonary Function Tests in Risk Stratification of Anatomic Lung Resection: A Retrospective Review. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2024, 18, 17534666241305954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Castro, R.; Vasconcello-Castillo, L.; Alsina-Restoy, X.; Solis-Navarro, L.; Burgos, F.; Puppo, H.; Vilaró, J. Respiratory Function in Patients Post-Infection by COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pulmonology 2021, 27, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, A.; Gross, S.; Lehnert, K.; Lücker, P.; Friedrich, N.; Nauck, M.; Bahlmann, S.; Fielitz, J.; Dörr, M. Longitudinal Clinical Features of Post-COVID-19 Patients—Symptoms, Fatigue and Physical Function at 3- and 6-Month Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Jian, W.; Su, Z.; Chen, M.; Peng, H.; Peng, P.; Lei, C.; Chen, R.; Zhong, N.; Li, S. Ab-normal Pulmonary Function in COVID-19 Patients at Time of Hospital Discharge. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2001217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerum, T.V.; Aaløkken, T.M.; Brønstad, E.; Aarli, B.; Ikdahl, E.; Lund, K.M.A.; Durheim, M.T.; Rodriguez, J.R.; Meltzer, C.; Tonby, K.; et al. Dyspnoea, Lung Function and CT Findings 3 Months after Hospital Admission for COVID-19. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2003448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, R.; Zhan, Q.; Ni, F.; Fang, S.; Lu, Y.; Ding, X.; et al. 3-Month, 6-Month, 9-Month, and 12-Month Respiratory Outcomes in Patients Following COVID-19-Related Hospitalisation: A Prospective Study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, M.E.B.; Leliveld, A.; Baalbaki, N.; Gach, D.; Van Der Lee, I.; Nossent, E.J.; Bloemsma, L.D.; Maitland-van Der Zee, A.H. Pulmonary Function 3–6 Months after Acute COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Multicentre Cohort Study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myall, K.J.; Mukherjee, B.; Castanheira, A.M.; Lam, J.L.; Benedetti, G.; Mak, S.M.; Preston, R.; Thillai, M.; Dewar, A.; Molyneaux, P.L.; et al. Persistent Post–COVID-19 Interstitial Lung Dis-ease. An Observational Study of Corticosteroid Treatment. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barisione, G.; Brusasco, V. Lung Diffusing Capacity for Nitric Oxide and Carbon Monoxide Following Mild-to-severe COVID-19. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e14748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefania, M.N.; Toma, C.; Bondor, C.I.; Maria, R.V.; Florin, P.; Adina, M.M. Long COVID and Lung Involvement: A One-Year Longitudinal, Real-Life Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kłos, K.; Jaskóła-Polkowska, D.; Plewka-Barcik, K.; Rożyńska, R.; Pietruszka-Wałęka, E.; Żabicka, M.; Kania-Pudło, M.; Maliborski, A.; Plicht, K.; Angielski, G.; et al. Pulmonary Function, Computed Tomography Lung Abnormalities, and Small Airway Disease after COVID-19: 3-, 6-, and 9-Month Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.; Dowds, J.; O’Brien, K.; Sheill, G.; Dyer, A.H.; O’Kelly, B.; Hynes, J.P.; Mooney, A.; Dunne, J.; Ni Cheallaigh, C.; et al. Persistent Poor Health after COVID-19 Is Not Associated with Respiratory Complications or Initial Disease Severity. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strumiliene, E.; Urbonienė, J.; Jurgauskiene, L.; Zeleckiene, I.; Bliudzius, R.; Malinauskiene, L.; Zablockiene, B.; Samuilis, A.; Jancoriene, L. Long-Term Pulmonary Sequelae and Immunological Markers in Patients Recovering from Severe and Critical COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Com-prehensive Follow-Up Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Data of Patients from 2021 | 1–3 Months After the Acute Episode | 4–7 Months After the Acute Episode | 9–12 Months After the Acute Episode | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 36 | n = 18 | n = 11 | p | ||||

| Age(Years) Mean(SD) Min–Max% | 52.22 (12.73) 26–76 | 54.78 (15.79) 27–79 | 53.50 (17.31) 27–77 | 0.41 | |||

| Urban/rural area (%) | 86/14 | 70/30 | 90/10 | - | |||

| Sex (female/male)% | 61/39 | 55/45 | 70/30 | - | |||

| Smoking history: smokers/non-smokers/former smokers/% NR * | 17/42/11/30 | 10/50/10/30 | 10/45/27/18 | - | |||

| COVID-19 Severity: Mild/moderate/severe% | 64/36 | 55/35/10 | 28/72 | ˂0.05 | |||

| Comorbidities% | ˂0.0001 | ||||||

| Hypertension% | 11 | 15 | 36% | ˂0.0001 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus% | 5 | 10 | 18% | ˂0.0001 | |||

| Respiratory disorders% | 14 | 15 | 2% | ˂0.0001 | |||

| Obesity% | 5 | 10 | 5% | ˂0.0005 | |||

| Thyroid disease% | 11 | - | - | ||||

| The most common post-COVID-19 symptoms: | |||||||

| Physical fatigue% | 69 | 40 | 60 | ˂0.005 | |||

| Cough% | 22 | 35 | 30 | ˂0.005 | |||

| Dyspnea% | 50 | 40 | 40 | ˂0.005 | |||

| Pulmonary function parameters | Mean (Stdev) | Min–Max | Mean (Stdev) | Min–Max | Mean (Stdev) | Min–Max | |

| SpO2% | 96.86 (1.53) | 93–99 | 96.5 (1.12) | 95–99 | 96.5 (1.11) | 95–99 | 0.189 |

| FVC% of predicted | 101.58 (12.03) | 72.5–129 | 103.5 (15.36) | 74.9–133 | 94.6 (8.80) | 83.6–110 | ˂0.05 |

| FEV1% | 104.0 (12.57) | 74.7–129 | 108.2 (16.7) | 78.4–147 | 96.28 (11.28) | 72.9–115 | ˂0.01 |

| IT | 84.05 (5.09) | 76–97.4 | 85.0 (4.39) | 75.8–90.1 | 85.05 (5.68) | 71.1–91.9 | 0.143 |

| MEF 50% | 100.66 (27.89) | 58.7–175 | 105.1 (28.85) | 59–158 | 110.15 (36.31) | 34.1–162 | ˂0.005 |

| MEF 25% | 88.38 (39.68) | 32.1–204 | 92.18 (28.18) | 40.7–129 | 96.22 (22.37) | 68.5–130 | 0.261 |

| DLCO% | 88.44 (16.33) | 57–122 | 92.18 (19.02) | 64–125 | 82.9 (10.05) | 72–104 | ˂0.001 |

| KCO% | 96.82 (13.76) | 69–137 | 96.7 (14.431) | 76–119 | 100.8 (10.41) | 83–118 | ˂0.01 |

| Demographic Data of Patients from 2022 | 3–6 Months After the Acute Episode | 7–12 Months After the Acute Episode | 14–22 Months After the Acute Episode | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 19 | n = 6 | n = 7 | |||||

| Age (years) Mean (SD) Min–Max | 59.55 (13.49) 22–77 | 65 (10.58) 54–81 | 64.28 (8.46) 46–85 | 0.53 | |||

| Urban/rural area (%) | 89/11 | 100/0 | 57/43 | - | |||

| Sex (female/male) (%) | 53/47 | 50/50 | 71/29 | - | |||

| Smoking history-smokers/non-smoker/former-smoker/UV * (%) | 18/52/15/15 | -/38/35/27 | 14/29/29/28 | - | |||

| COVID-19 Severity: Mild/moderate/severe | 43/42/15 | 66/34/- | 29/71/- | - | |||

| Comorbidities (%) | 0.85 | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus% | 20 | - | 10 | - | |||

| Hypertension% | 35 | 14% | 30 | - | |||

| Neoplasma% | 10 | - | - | - | |||

| CIC% Thyroid disease% | - 11 | 14 - | - - | - | |||

| The most common post-COVID-19 symptoms: | - | ||||||

| Physical fatigue% | 45 | 28 | 40 | - | |||

| Caugh% | 20 | 10 | 50 | - | |||

| Dyspnea% | 45 | 43 | 60 | - | |||

| Pulmonary function parameters | Mean (Stdev) | Min–Max | Mean (Stdev) | Min–Max | Mean (Stdev) | Min–Max | |

| SpO2% | 96.61 (2.29) | 90–99 | 97.83 (0.69) | 96–99 | 96.86 (1.46) | 87–99 | 0.14 |

| FVC % of predicted | 95.57 (14.36) | 66.7–117 | 117.5 (17.73) | 86.1–145 | 100.9 (3.62) | 51.8–105 | ˂0.05 |

| FEV1% | 97.2 (20.41) | 43.9–128 | 116.97 (27.30) | 73.7–162 | 90.81 (21.10) | 37.3–108 | ˂0.05 |

| IT | 85.7 (11.32) | 47.1–98.1 | 83.78 (8.34) | 64.7–92.7 | 79.93 (8.12) | 61.6–88.7 | 0.89 |

| MEF 50% | 100.08 (23.01) | 12.4–135 | 109.9 (38.38) | 41.4–153 | 82.71 (21.06) | 40.10–105 | |

| MEF 25% | 92.59 (34.71) | 16–166 | 92.8 (50.67) | 33.5–172 | 70.77 (25.46) | 30.2–110 | 0.076 |

| DLCO% | 83.78 (17.03) | 45–120 | 91.40 (13.38) | 72–110 | 79.40 (9.13) | 68–92 | 0.34 |

| KCO% | 96.44 (19.09) | 68–134 | 93.10 (16.15) | 75–120 | 88.20 (12.81) | 75–109 | 0.68 |

| Mann–Whitney U Test Post-COVID 2021/2022 by Severity Form/COVID-19 Marked Tests are Significant at p ˂ 0.05 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCS (2021) | Rank Sum | Rank Sum | U | Z | p Value | Z | p Value | Valid N Mild Form | Valid N Moderate Form |

| Age | 981.5 | 1163.5 | 240.5 | −3.62 | 0.0003 | −3.62 | 0.0003 | 36 | 27 |

| Time since the acute episode | 1105.0 | 1040.0 | 364.0 | −1.98 | 0.0481 | −2.02 | 0.0429 | 36 | 27 |

| FVC% from predicted | 1501.5 | 643.5 | 265.5 | 3.29 | 0.0010 | 3.29 | 0.0010 | 36 | 27 |

| FEV1% | 1430.0 | 715.0 | 337.0 | 2.34 | 0.0195 | 2.34 | 0.0194 | 36 | 27 |

| DLCO% | 1491.5 | 653.5 | 275.5 | 3.15 | 0.0016 | 3.16 | 0.0016 | 36 | 27 |

| KCO% | 1485.5 | 659.5 | 281.5 | 3.08 | 0.0021 | 3.08 | 0.0021 | 36 | 27 |

| PCS (2022) | |||||||||

| DLCO% | 409.0 | 186.0 | 50.0 | 3.23 | 0.0013 | 3.23 | 0.0012 | 18 | 14 |

| KCO% | 401.0 | 194.0 | 58.0 | 2.95 | 0.0032 | 2.96 | 0.0031 | 18 | 14 |

| Eigenvalues (post-COVID 2021.sta) Extraction: Principal components | ||||

| Eigenvalue | % Total | Cumulative | Cumulative | |

| Factor 1 | 6.179288 | 38.62055 | 6.17929 | 38.62055 |

| Factor 2 | 3.038773 | 18.99233 | 9.21806 | 57.61288 |

| Factor 3 | 1.800743 | 11.25464 | 11.01880 | 68.86752 |

| Eigenvalues (post-COVID/2022.sta) Extraction: Principal components | ||||

| Eigenvalue | % Total | Cumulative | Cumulative | |

| Factor 1 | 6.351194 | 35.28441 | 6.35119 | 35.28441 |

| Factor 2 | 3.952570 | 21.95872 | 10.30376 | 57.24314 |

| Factor 3 | 2.231929 | 12.39961 | 12.53569 | 69.64274 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Popa, D.R.; Marginean, C.; Dobrin, M.E.; Crisan Dabija, R.A.; Melinte, O.-E.; Dumitrache-Rujinski, S.; Stavarache, I.E.; Cioroiu, I.-B.; Trofor, A.C. Impact of COVID-19 on Respiratory Function: A Post-Recovery Comparative Assessment. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020717

Popa DR, Marginean C, Dobrin ME, Crisan Dabija RA, Melinte O-E, Dumitrache-Rujinski S, Stavarache IE, Cioroiu I-B, Trofor AC. Impact of COVID-19 on Respiratory Function: A Post-Recovery Comparative Assessment. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):717. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020717

Chicago/Turabian StylePopa, Daniela Robu, Corina Marginean, Mona Elisabeta Dobrin, Radu Adrian Crisan Dabija, Oana-Elena Melinte, Stefan Dumitrache-Rujinski, Ioan Emanuel Stavarache, Ionel-Bogdan Cioroiu, and Antigona Carmen Trofor. 2026. "Impact of COVID-19 on Respiratory Function: A Post-Recovery Comparative Assessment" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020717

APA StylePopa, D. R., Marginean, C., Dobrin, M. E., Crisan Dabija, R. A., Melinte, O.-E., Dumitrache-Rujinski, S., Stavarache, I. E., Cioroiu, I.-B., & Trofor, A. C. (2026). Impact of COVID-19 on Respiratory Function: A Post-Recovery Comparative Assessment. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020717