Laparoscopic Resection Rectopexy with Transanal Specimen Extraction for Complete Rectal Prolapse: Retrospective Cohort Study of Functional Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Scoring Systems

2.3.1. Low Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS) Score

2.3.2. Wexner Incontinence Score (WIS)

2.3.3. Obstructed Defecation Syndrome (ODS) Score

2.4. Study Groups

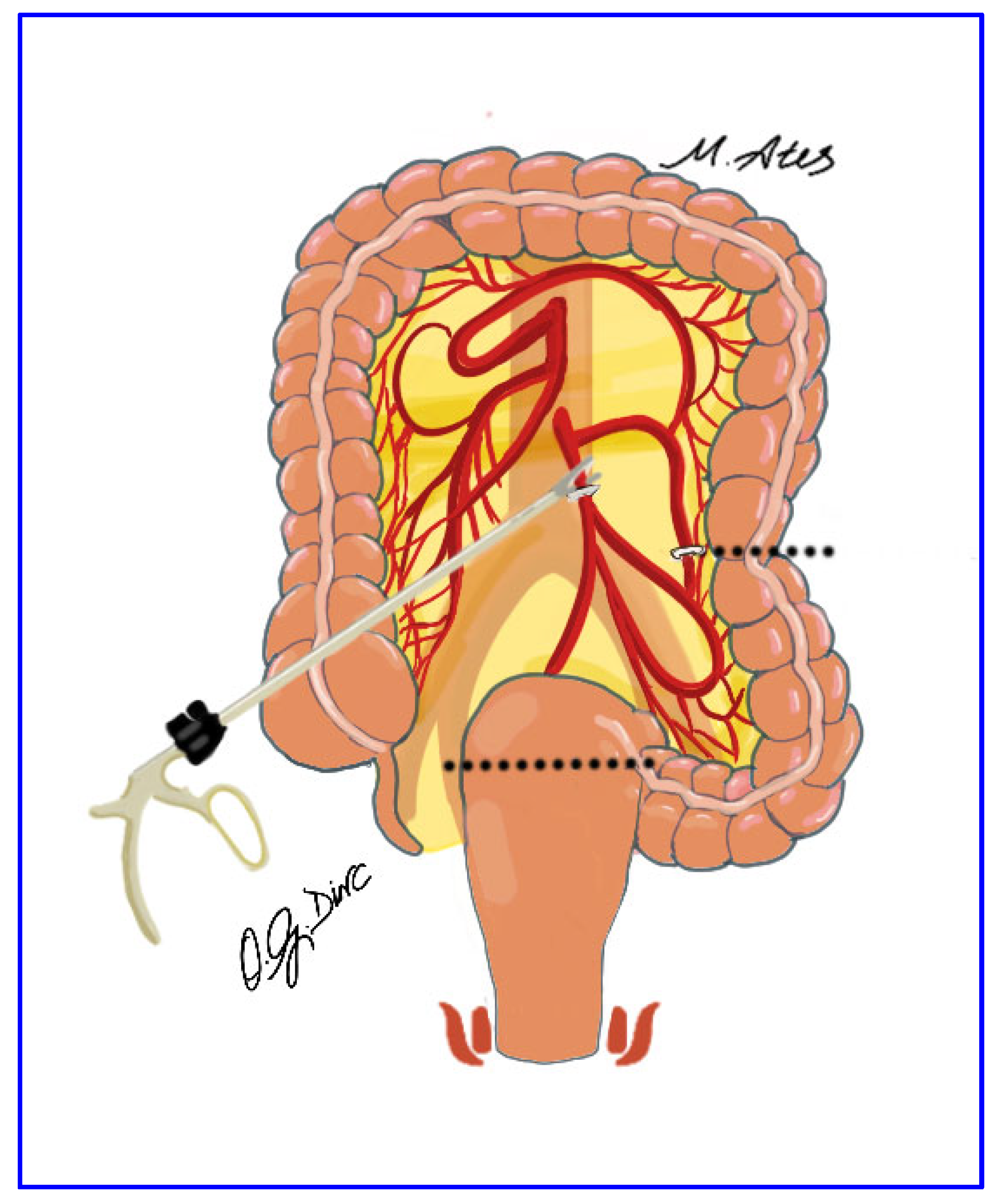

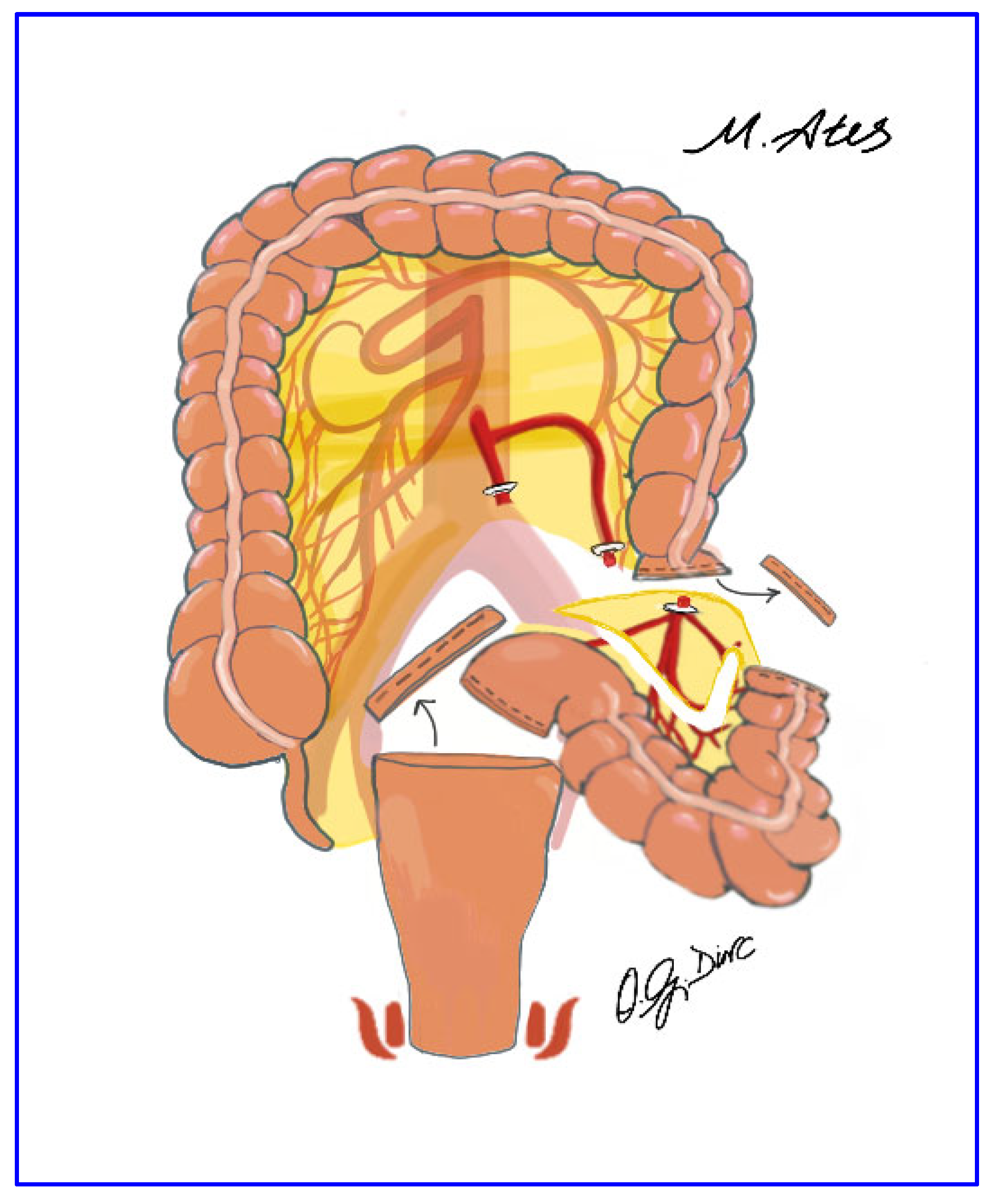

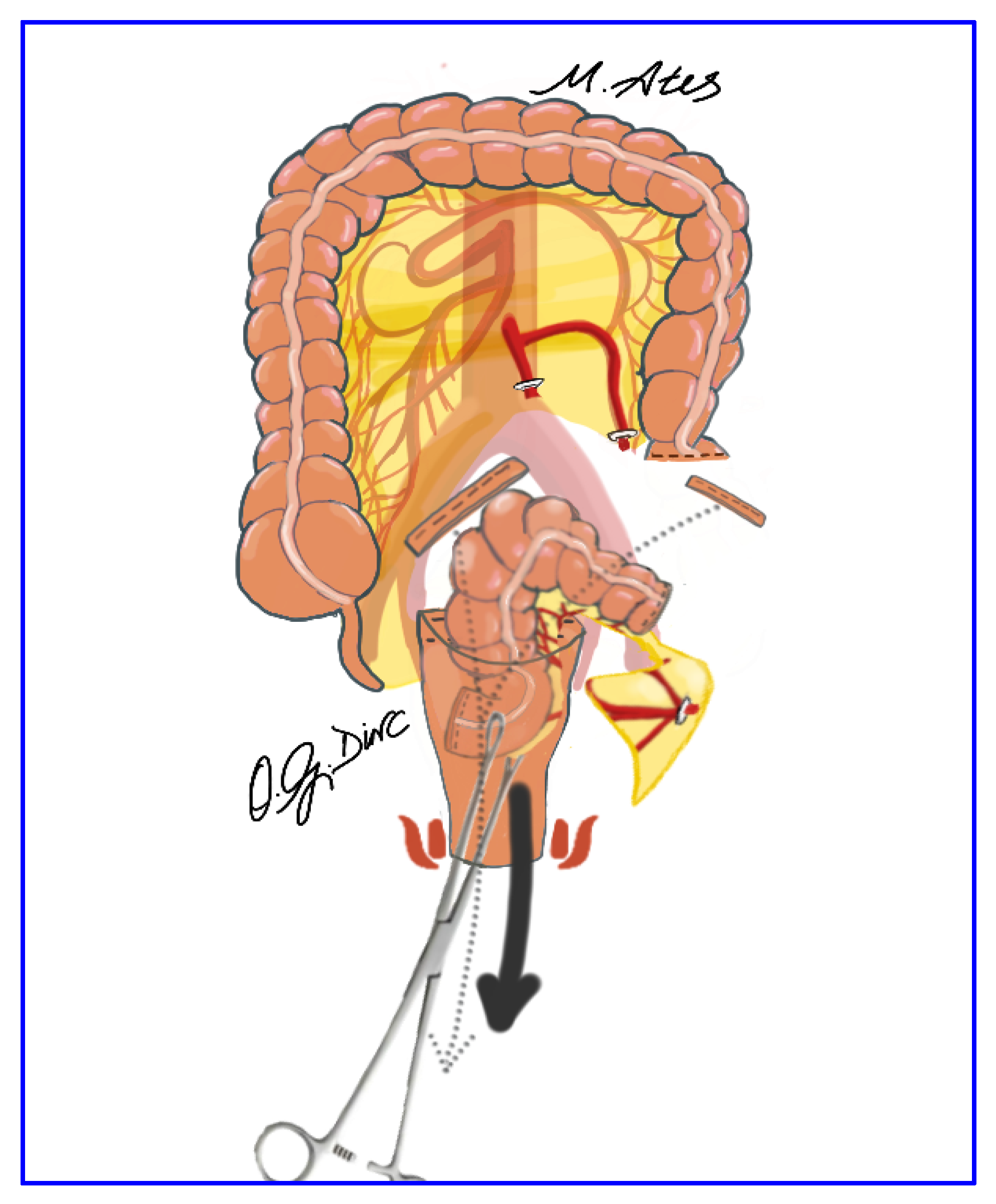

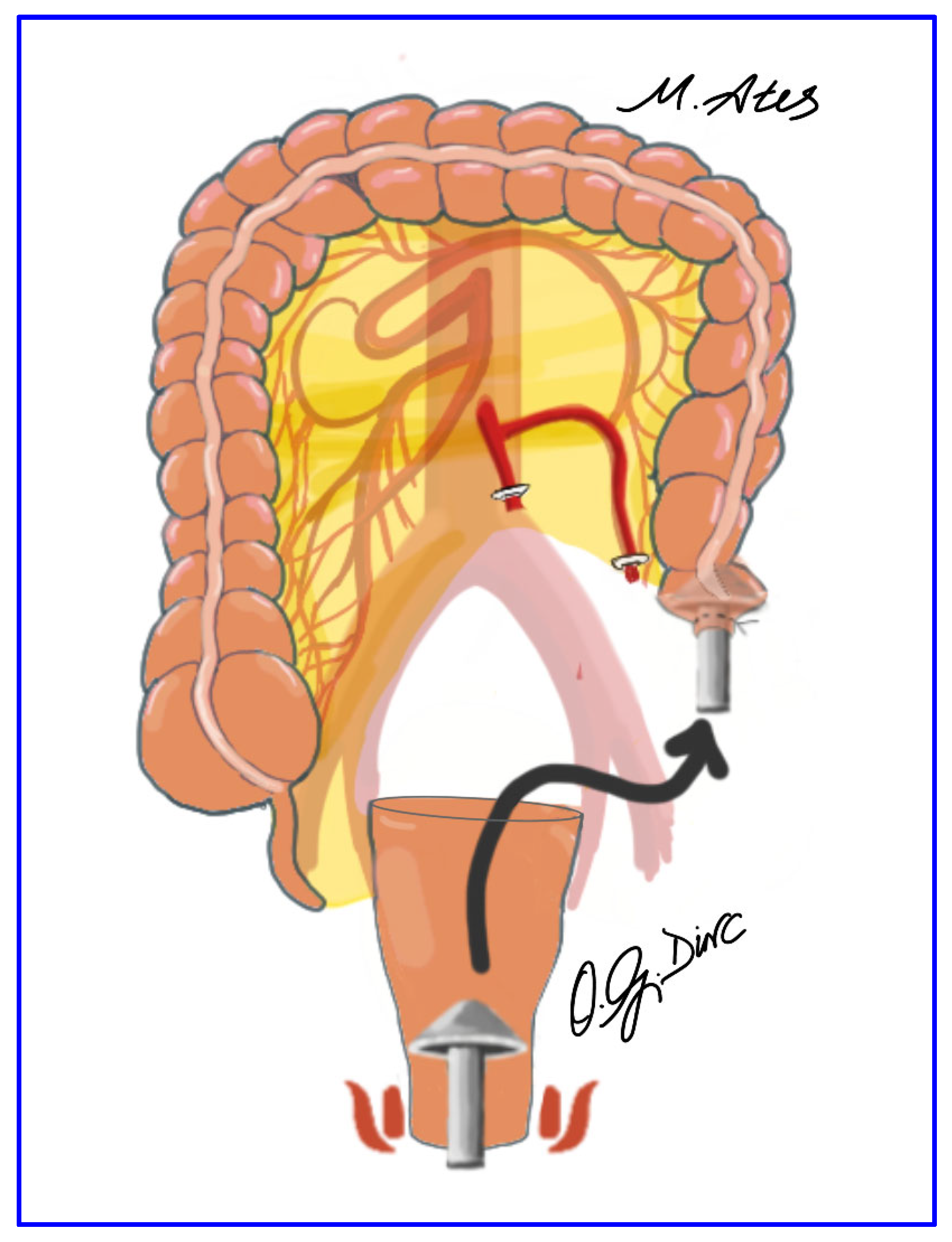

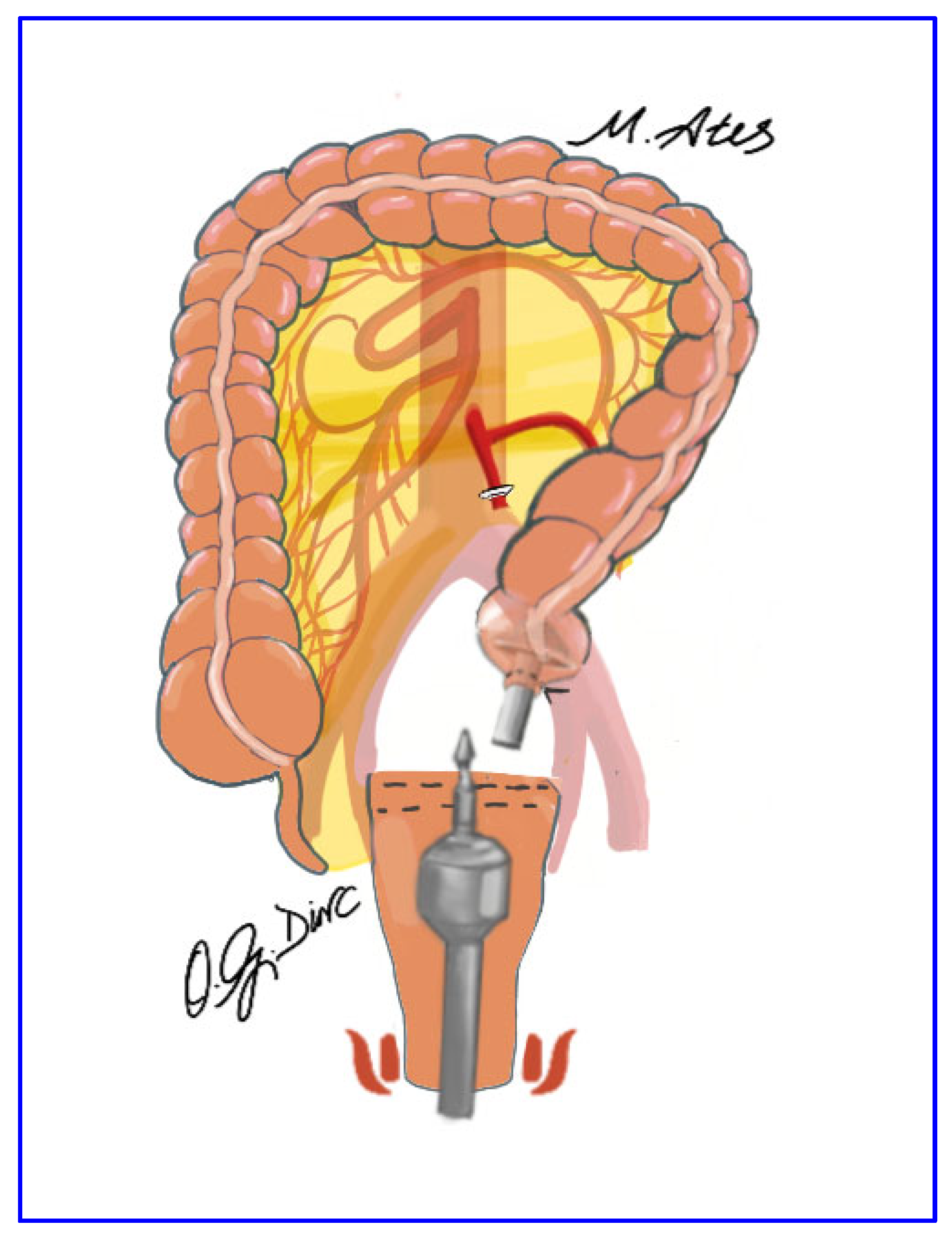

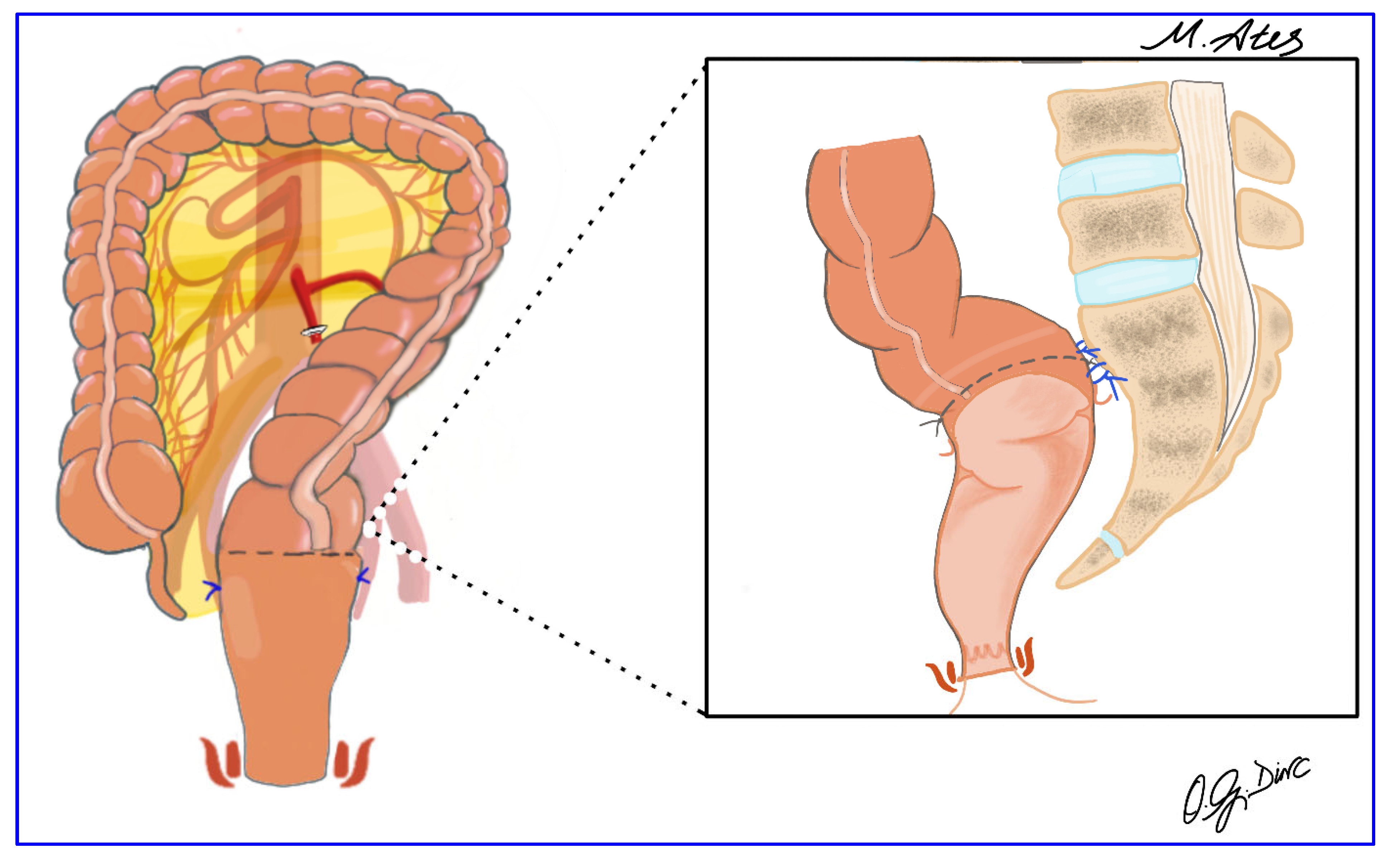

2.5. Surgical Technique

2.6. Follow Up

2.7. Study Protocol, Ethical Approval, and Funding

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Entire Study Cohort

3.2. Longitudinal Changes in ODS, LARS, and WIS Scores Across the Entire Study Cohort

3.3. Sex-Based Comparative Analysis of Clinical and Functional Outcomes

3.4. Sex-Based Longitudinal Changes in ODS, LARS and WIN Scores

3.5. BMI-Based Comparative Analysis of Clinical and Functional Outcomes

3.6. BMI-Based Longitudinal Changes in ODS, LARS and WIN Scores

3.7. Age-Based Comparative Analysis of Clinical and Functional Outcomes

3.8. Age-Based Longitudinal Changes in ODS, LARS and WIN Scores

3.9. Surgical Complications

3.10. Surgical Outcomes

3.11. Temporal Effects, Effect Sizes and Post Hoc Power Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schiedeck, T.H.; Schwandner, O.; Scheele, J.; Farke, S.; Bruch, H.P. Rectal prolapse: Which surgical option is appropriate? Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2005, 390, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, R.; Hu, K. History of the Treatment of Rectal Prolapse. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2025, 38, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruc, M.; Erol, T. Current diagnostic tools and treatment modalities for rectal prolapse. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 3680–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Wu, H.; Mu, S.; Li, X.Y.; Zhen, Y.H.; Li, H.Y. Surgical approaches for complete rectal prolapse. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 17, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairaluoma, M.V.; Kellokumpu, I.H. Epidemiologic aspects of complete rectal prolapse. Scand. J. Surg. 2005, 94, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.; Geng, J.; Tang, J.; Yang, X. The relationship between obstructed defecation and true rectocele in patients with pelvic organ prolapse. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompetto, M.; Tutino, R.; Realis Luc, A.; Novelli, E.; Gallo, G.; Clerico, G. Altemeier’s procedure for complete rectal prolapse; outcome and function in 43 consecutive female patients. BMC Surg. 2019, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucciani, F. Rectal Prolapse: Pathophysiology. In Rectal Prolapse: Diagnosis and Clinical Management; Altomare, D.F., Pucciani, F., Eds.; Springer: Milano, Italy, 2008; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Altomare, D.F.; Spazzafumo, L.; Rinaldi, M.; Dodi, G.; Ghiselli, R.; Piloni, V. Set-up and statistical validation of a new scoring system for obstructed defaecation syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2008, 10, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Yang, Q. A bibliometric analysis of surgical treatment for rectal prolapse. Medicine 2025, 104, e43763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emile, S.H.; Wignakumar, A.; Horesh, N.; Garoufalia, Z.; Strassmann, V.; Boutros, M.; Wexner, S.D. Systematic literature review and meta-analysis of surgical treatment of complete rectal prolapse in male patients. Tech. Coloproctol. 2024, 28, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catanzarite, T.; Klaristenfeld, D.D.; Tomassi, M.J.; Zazueta-Damian, G.; Alperin, M. Recurrence of Rectal Prolapse After Surgical Repair in Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Dis. Colon Rectum 2018, 61, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, J.A. Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Medical Management of Rectal Prolapse. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2017, 30, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.; Richter, H.E. Impact of fecal incontinence and its treatment on quality of life in women. Womens Health 2015, 11, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Park, Y.; Kim, M.; Lee, S. Interaction and main effects of physical and depressive symptoms on quality of life in Korean women seeking care for rectal prolapse: A cross-sectional observational study. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2021, 27, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordeianou, L.; Hicks, C.W.; Kaiser, A.M.; Alavi, K.; Sudan, R.; Wise, P.E. Rectal prolapse: An overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and patient-specific management strategies. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2014, 18, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshatian, L.; Lee, A.; Trickey, A.W.; Arnow, K.D.; Gurland, B.H. Rectal Prolapse: Age-Related Differences in Clinical Presentation and What Bothers Women Most. Dis. Colon Rectum 2021, 64, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dhuwaib, Y.; Pandyan, A.; Knowles, C.H. Epidemiological trends in surgery for rectal prolapse in England 2001-2012: An adult hospital population-based study. Colorectal Dis. 2020, 22, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotouras, A.; Murphy, J.; Boyle, D.J.; Allison, M.; Williams, N.S.; Chan, C.L. Assessment of female patients with rectal intussusception and prolapse: Is this a progressive spectrum of disease? Dis. Colon Rectum 2013, 56, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Martellucci, J.; Pellino, G.; Ghiselli, R.; Infantino, A.; Pucciani, F.; Trompetto, M. Consensus Statement of the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR): Management and treatment of complete rectal prolapse. Tech. Coloproctol. 2018, 22, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madiba, T.E.; Baig, M.K.; Wexner, S.D. Surgical management of rectal prolapse. Arch. Surg. 2005, 140, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, A.; Gray, R.G.; Middleton, L.J.; Harding, J.; Hills, R.K.; Armitage, N.C.; Buckley, L.; Northover, J.M. PROSPER: A randomised comparison of surgical treatments for rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. 2013, 15, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tou, S.; Brown, S.R.; Malik, A.I.; Nelson, R.L. Surgery for complete rectal prolapse in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, Cd001758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashari, L.H.; Lumley, J.W.; Stevenson, A.R.; Stitz, R.W. Laparoscopically-assisted resection rectopexy for rectal prolapse: Ten years’ experience. Dis. Colon Rectum 2005, 48, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoist, S.; Taffinder, N.; Gould, S.; Chang, A.; Darzi, A. Functional results two years after laparoscopic rectopexy. Am. J. Surg. 2001, 182, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruch, H.P.; Herold, A.; Schiedeck, T.; Schwandner, O. Laparoscopic surgery for rectal prolapse and outlet obstruction. Dis. Colon Rectum 1999, 42, 1189–1194; discussion 1194–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formijne Jonkers, H.A.; Draaisma, W.A.; Wexner, S.D.; Broeders, I.A.; Bemelman, W.A.; Lindsey, I.; Consten, E.C. Evaluation and surgical treatment of rectal prolapse: An international survey. Colorectal Dis. 2013, 15, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Reibetanz, J.; Boenicke, L.; Germer, C.T.; Jayne, D.; Isbert, C. Quality of life after laparoscopic resection rectopexy. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2012, 27, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechaux, D.; Trebuchet, G.; Siproudhis, L.; Campion, J.P. Laparoscopic rectopexy for full-thickness rectal prolapse: A single-institution retrospective study evaluating surgical outcome. Surg. Endosc. 2005, 19, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Schneider, C.; Scheidbach, H.; Yildirim, C.; Bruch, H.P.; Konradt, J.; Bärlehner, E.; Köckerling, F. Laparoscopic treatment of rectal prolapse: Experience gained in a prospective multicenter study. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2002, 387, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Can, M.F.; Asoglu, O.; Lapsekili, E.; Demirbas, S. Laparoscopic resection rectopexy with preservation of the superior rectal artery, natural orifice specimen extraction, and assessment of anastomotic perfusion using indocyanine green imaging in rectal prolapse. Dis. Colon Rectum 2014, 57, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Y.; Tang, R.; Yuan, S.; Xie, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, C. The feasibility, safety and short-term clinical efficacy of laparoscopic resection rectopexy with natural orifice specimen extraction surgery for the treatment of complete rectal prolapse. BMC Surg. 2025, 25, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, K.H.; Breithaupt, W.; Varga, G.; Schulz, T.; Reinisch, A.; Josipovic, N. Transanal hybrid colon resection: From laparoscopy to NOTES. Surg. Endosc. 2013, 27, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolthuis, A.M.; Van Geluwe, B.; Fieuws, S.; Penninckx, F.; D’Hoore, A. Laparoscopic sigmoid resection with transrectal specimen extraction: A systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2012, 14, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zattoni, D.; Popeskou, G.S.; Christoforidis, D. Left colon resection with transrectal specimen extraction: Current status. Tech. Coloproctol. 2018, 22, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompeu, B.F.; Guerra, L.S.; Guedes, L.; Brunini, J.H.; Delgado, L.M.; Poli de Figueiredo, S.M.; Formiga, F.B. Natural Orifice Extraction Techniques (Natural Orifice Specimen Extraction and Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery) for Left-Sided Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2025, 35, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; He, M.; Liu, Z.; Chen, K.; Denis, K.s.; Zhang, J.; Zou, J.; Semchenko, B.S.; Efetov, S.K. Evaluation of the efficacy of natural orifice specimen extraction surgery versus conventional laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2025, 27, e17279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mui, J.; Sarofim, M.; Cheng, E.; Gilmore, A. Laparoscopic natural orifice specimen extraction for diverticular disease: A systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 2025, 39, 3049–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wang, J.Q. Comparative analysis of safety and effectiveness between natural orifice specimen extraction and conventional transabdominal specimen extraction in robot-assisted colorectal cancer resection through systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Robot Surg. 2024, 18, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Huang, X.Z.; Gao, P.; Zhao, J.H.; Song, Y.X.; Sun, J.X.; Chen, X.W.; Wang, Z.N. Laparoscopic resection with natural orifice specimen extraction versus conventional laparoscopy for colorectal disease: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2015, 30, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, N.M.; Kalkdijk-Dijkstra, A.J.; van Westreenen, H.L.; Broens, P.; Pierie, J.; van der Heijden, J.; Klarenbeek, B.R. Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation After Rectal Cancer Surgery One-year follow-up of a Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial (FORCE trial). Ann. Surg. 2024, 281, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Chokshi, R.V. Low Anterior Resection Syndrome. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2020, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.T.; Lv, Y.M.; Zhou, S.C.; Luo, D.Y.; Sun, H.; Lao, W.F.; Zhou, W. Evaluation of surgical strategy for low anterior resection syndrome using preoperative low anterior resection syndrome score in China. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 17, 100910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, I.E.K.; Åkervall, S.; Molin, M.; Milsom, I.; Gyhagen, M. Severity and impact of accidental bowel leakage two decades after no, one, or two sphincter injuries. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, 447.e1–447.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, J.; Swatton, A.; Taylor, C.; Wilson, A.; Norton, C. Managing Bowel Symptoms After Sphincter-Saving Rectal Cancer Surgery: A Scoping Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liptak, P.; Duricek, M.; Banovcin, P. Diagnostic tools for fecal incontinence: Scoring systems are the crucial first step. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, A.; Marano, L.; Talento, P.; Brusciano, L.; Pezzolla, A.; Izzo, D.; Antropoli, C.; D’Aniello, F.; Di Sarno, G.; Minieri, G.; et al. Transverse perineal support improves long-term outcomes in patients undergoing stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation syndrome: A multicenter observational case-control study. Ann. Coloproctol. 2025, 41, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Ryan, É.J.; Davey, M.G.; McHugh, F.T.; Creavin, B.; Whelan, M.C.; Kelly, M.E.; Neary, P.C.; Kavanagh, D.O.; O’Riordan, J.M. Mechanical bowel preparation and antibiotics in elective colorectal surgery: Network meta-analysis. BJS Open 2023, 7, zrad040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerdán Santacruz, C.; Gancedo Quintana, Á.; Cerdán Miguel, J. Delorme’s Procedure for Rectal Prolapse. Dis. Colon Rectum 2022, 65, e956–e957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Dizer, A.M.; Kreis, M.E.; Gröne, J. Radiological Changes After Resection Rectopexy in Patients with Rectal Prolapse-Influence on Clinical Symptoms and Quality of Life. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2018, 22, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsunoda, A.; Yasuda, N.; Yokoyama, N.; Kamiyama, G.; Kusano, M. Delorme’s procedure for rectal prolapse: Clinical and physiological analysis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2003, 46, 1260–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frykman, H.M.; Goldberg, S.M. The surgical treatment of rectal procidentia. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1969, 129, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, J.D.; Rothenberger, D.A.; Buls, J.G.; Goldberg, S.M.; Nivatvongs, S. The management of procidentia. 30 years’ experience. Dis. Colon Rectum 1985, 28, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ates, M.; Dirican, A.; Kinaci, E.; Yonder, H. Laparoscopic resection rectopexy with trans-anal specimen extraction for complete rectal prolapse: Preliminary results. In Proceedings of the 10th Scientific and Annual Meeting of the European Society of Coloproctology, Dublin, Ireland, 23–25 September 2015; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar, J.S.; Prabhakaran, R.; Akbar, S.; Rajkumar, A.J.; Venkatesan, G.; Rajkumar, S. Totally laparoscopic resection rectopexy with transanal extraction of the specimen. Saudi Surg. J. 2018, 6, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, W.; Karlbom, U.; Påhlman, L.; Nilsson, S.; Ejerblad, S. Functional results after abdominal suture rectopexy for rectal prolapse or intussusception. Eur. J. Surg. 1996, 162, 905–911. [Google Scholar]

- Speakman, C.T.; Madden, M.V.; Nicholls, R.J.; Kamm, M.A. Lateral ligament division during rectopexy causes constipation but prevents recurrence: Results of a prospective randomized study. Br. J. Surg. 1991, 78, 1431–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madbouly, K.M.; Senagore, A.J.; Delaney, C.P.; Duepree, H.J.; Brady, K.M.; Fazio, V.W. Clinically based management of rectal prolapse. Surg. Endosc. 2003, 17, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deen, K.I.; Grant, E.; Billingham, C.; Keighley, M.R. Abdominal resection rectopexy with pelvic floor repair versus perineal rectosigmoidectomy and pelvic floor repair for full-thickness rectal prolapse. Br. J. Surg. 1994, 81, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauwereins, L.; D’Hoore, A.; Coeckelberghs, E.; Fieuws, S.; Wolthuis, A.; Bislenghi, G.; Van Molhem, Y.; Van Geluwe, B.; Debrun, L.; Devoogdt, N.; et al. A 2-year prospective study on the evolution of Low Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS) following rectal cancer surgery. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2025, 40, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, C.; Wells, C.; O’Grady, G.; Bissett, I.P. Defining low anterior resection syndrome: A systematic review of the literature. Colorectal Dis. 2017, 19, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanculea, F.; Ungureanu, C.O.; Roca, D.; Ginghina, O.; Mihailov, R.; Grama, F.; Iordache, N. The impact of Low-Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS) on the Quality of Life in Rectal Cancer Survivors: A Narrative Review. Maedica A J. Clin. Med. 2025, 20, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirbas, S.; Akin, M.L.; Kalemoglu, M.; Ogün, I.; Celenk, T. Comparison of laparoscopic and open surgery for total rectal prolapse. Surg. Today 2005, 35, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, H.; Hohenberger, W. Laparoscopic resection rectopexy for rectal prolapse. Dis. Colon Rectum 2005, 48, 1800–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubert, T.; Bader, F.G.; Kleemann, M.; Esnaashari, H.; Bouchard, R.; Hildebrand, P.; Schlöricke, E.; Bruch, H.P.; Roblick, U.J. Outcome analysis of elderly patients undergoing laparoscopic resection rectopexy for rectal prolapse. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2012, 27, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrenot, C.; Germain, A.; Scherrer, M.L.; Ayav, A.; Brunaud, L.; Bresler, L. Long-term outcomes of robot-assisted laparoscopic rectopexy for rectal prolapse. Dis. Colon Rectum 2013, 56, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihedioha, U.; Mackay, G.; Leung, E.; Molloy, R.G.; O’Dwyer, P.J. Laparoscopic colorectal resection does not reduce incisional hernia rates when compared with open colorectal resection. Surg. Endosc. 2008, 22, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winslow, E.R.; Fleshman, J.W.; Birnbaum, E.H.; Brunt, L.M. Wound complications of laparoscopic vs open colectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2002, 16, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, J.; Costantino, F.; Cahill, R.A.; D’Agostino, J.; Morales, A.; Mutter, D.; Marescaux, J. Laparoscopic resection with transanal specimen extraction for sigmoid diverticulitis. Br. J. Surg. 2011, 98, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolthuis, A.M.; de Buck van Overstraeten, A.; D’Hoore, A. Laparoscopic natural orifice specimen extraction-colectomy: A systematic review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 12981–12992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuschillo, G.; Selvaggi, L.; Cuellar-Gomez, H.; Pescatori, M. Comparison between perineal and abdominal approaches for the surgical treatment of recurrent external rectal prolapse: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2025, 40, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zou, Q.; Xian, Z.; Su, D.; Liu, C.; Lu, L.; Luo, M.; Chen, Z.; Cai, K.; Gao, H.; et al. External rectal prolapse: Abdominal or perineal repair for men? A retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2022, 10, goac007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedberg, J.; Graf, W.; Pekkari, K.; Hjern, F. Comparison of four surgical approaches for rectal prolapse: Multicentre randomized clinical trial. BJS Open 2022, 6, zrab140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellino, G.; Fuschillo, G.; Simillis, C.; Selvaggi, L.; Signoriello, G.; Vinci, D.; Kontovounisios, C.; Selvaggi, F.; Sciaudone, G. Abdominal versus perineal approach for external rectal prolapse: Systematic review with meta-analysis. BJS Open 2022, 6, zrac018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrle, F.; Sandra-Petrescu, F.; Rothenhoefer, S.; Hardt, J.; Seyfried, S.; Joos, A.; Herold, A.; Bussen, D.; Post, S.; Brunner, M.; et al. Laparoscopic Resection Rectopexy Versus Delorme’s Procedure In Full-thickness Rectal Prolapse: A Randomized Multicenter Trial (DELORES-RCT). Ann. Surg. 2025, 282, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohapatra, K.C.; Swain, N.; Patro, S.; Sahoo, A.K.; Sahoo, A.K.; Mishra, A.K. Laparoscopic Versus Open Rectopexy for Rectal Prolapse: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cureus 2021, 13, e14175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Statistical Features | Female | Male | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SD) | 48 (12) | 39 (16) | 45 (14) | 0.024 |

| 95%CI | [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] | [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] | [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] | ||

| ASA Score | ASA I | 20 (62.5) | 16 (76.2) | 36 (67.9) | 0.374 |

| ASA II | 12 (37.5) | 5 (23.8) | 17 (32.1) | ||

| BMI | Mean (SD) | 27.4 (3.6) | 26.8 (3.5) | 27.1 (3.5) | 0.544 |

| 95%CI | [26.1–28.7] | [25.2–28.3] | [26.1–28.1] | ||

| Hospital Stay | Mean (SD) | 5 (2) | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | 0.529 |

| 95%CI | [4,5,6] | [3,4,5,6,7,8] | [4,5,6] | ||

| ODS (Preop) | Mean (SD) | 12.2 (3.2) | 13.6 (2.9) | 12.8 (3.2) | 0.125 |

| 95%CI | [11.1–13.4] | [12.3–15.0] | [11.9–13.7] | ||

| ODS (POD90) | Mean (SD) | 2.7 (2.5) | 1.9 (1.2) | 2.4 (2.1) | 0.148 |

| 95%CI | [1.8–3.6] | [1.4–2.4] | [1.8–2.9] | ||

| ODS (POD180) | Mean (SD) | 4.3 (2.3) | 4.1 (2.1) | 4.2 (2.2) | 0.732 |

| 95%CI | [3.5–5.2] | [3.2–5.0] | [3.6–4.8] | ||

| ODS (POD365) | Mean (SD) | 5.2 (3.1) | 5.2 (2.6) | 5.2 (2.9) | 0.981 |

| 95%CI | [4.1–6.3] | [4.0–6.4] | [4.4–6.0] | ||

| LARS (POD90) | Mean (SD) | 18.6 (13.2) | 17.1 (12.1) | 18.0 (12.7) | 0.694 |

| 95%CI | [13.8–23.3] | [11.6–22.7] | [14.5–21.5] | ||

| LARS (POD180) | Mean (SD) | 9.0 (6.9) | 8.6 (6.6) | 8.8 (6.8) | 0.836 |

| 95%CI | [6.5–11.5] | [5.6–11.6] | [6.9–10.7] | ||

| LARS (POD365) | Mean (SD) | 4.0 (4.8) | 2.9 (3.3) | 3.5 (4.2) | 0.341 |

| 95%CI | [2.3–5.7] | [1.4–4.3] | [2.4–4.7] | ||

| WIS (Preop) | Mean (SD) | 4.0 (4.0) | 3.9 (3.7) | 4.0 (3.9) | 0.874 |

| 95%CI | [2.6–5.5] | [2.2–5.5] | [2.9–5.0] | ||

| WIS (POD90) | Mean (SD) | 9.2 (5.2) | 6.2 (4.6) | 8.1 (5.2) | 0.037 |

| 95%CI | [7.4–11.1] | [4.2–8.3] | [6.6–9.5] | ||

| WIS (POD180) | Mean (SD) | 3.5 (4.3) | 2.6 (2.8) | 3.2 (3.7) | 0.407 |

| Min-Max | [2.0–5.0] | [1.3–3.9] | [2.1–4.2] | ||

| WIS (POD365) | Mean (SD) | 2.6 (3.3) | 2.1 (2.5) | 2.4 (3.0) | 0.573 |

| 95%CI | [1.4–3.8] | [1.0–3.3] | [1.6–3.3] | ||

| Follow up (mo) | Mean (SD) | 77.4 (19.9) | 83.0 (18.7) | 79.6 (19.5) | 0.312 |

| 95%CI | [70.2–84.6] | [74.4–91.5] | [74.2–85.0] |

| Parameters | Statistical Features | BMI < 25 | BMI ≥ 25 | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SD) | 45 (14) | 44 (14) | 45 (14) | 0.739 |

| 95%CI | [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] | [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] | [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] | ||

| Gender | Male | 9 (50) | 12 (34.3) | 21 (39.6) | 0.417 |

| Female | 9 (50) | 23 (65.7) | 32 (60.4) | ||

| ASA Score | ASA I | 12 (66.7) | 24 (68.6) | 36 (67.9) | 1.000 |

| ASA II | 6 (33.3) | 11 (31.4) | 17 (32.1) | ||

| Hospital Stay | Mean (SD) | 6 (6) | 5 (2) | 0.148 | |

| 95%CI | [3,4,5,6,7,8,9] | [4,5] | |||

| ODS (Preop) | Mean (SD) | 13.6 (3.6) | 12.4 (2.9) | 12.8 (3.2) | 0.212 |

| 95%CI | [11.8–15.3] | [11.4–13.4 | [11.9–13.7] | ||

| ODS (POD90) | Mean (SD) | 2.8 (2.8) | 2.1 (1.6) | 2.4 (2.1) | 0.301 |

| 95%CI | [1.4–4.2] | [1.6–2.7] | [1.8–2.9] | ||

| ODS (POD180) | Mean (SD) | 4.7 (2.5) | 4.0 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.2) | 0.306 |

| 95%CI | [3.4–5.9] | [3.3–4.7] | [3.6–4.8] | ||

| ODS (POD365) | Mean (SD) | 5.3 (3.0) | 5.2 (2.9) | 5.2 (2.9) | 0.850 |

| 95%CI | [3.9–6.8] | [4.2–6.2] | [4.4–6.0] | ||

| LARS (POD90) | Mean (SD) | 16.0 (12.0) | 19.0 (13.1) | 18.0 (12.7) | 0.415 |

| 95%CI | [10.1–21.9] | [14.5–23.5] | [14.5–21.5] | ||

| LARS (POD180) | Mean (SD) | 8.6 (6.9) | 8.9 (6.8) | 8.8 (6.8) | 0.879 |

| 95%CI | [5.2–12.0] | [6.6–11.3] | [6.9–10.7] | ||

| LARS (POD365) | Mean (SD) | 4.5 (5.2) | 3.1 (3.6) | 3.5 (4.2) | 0.243 |

| 95%CI | [1.9–7.1] | [1.8–4.3] | [2.4–4.7] | ||

| WIS (Preop) | Mean (SD) | 4.6 (4.2) | 3.7 (3.7) | 4.0 (3.9) | 0.429 |

| 95%CI | [2.5–6.7] | [2.4–4.9] | [2.9–5.0] | ||

| WIS (POD90) | Mean (SD) | 7.7 (4.9) | 8.2 (5.4) | 8.1 (5.2) | 0.739 |

| 95%CI | [5.3–10.2] | [6.4–10.1] | [6.6–9.5] | ||

| WIS (POD180) | Mean (SD) | 4.1 (4.6) | 2.7 (3.2) | 3.2 (3.7) | 0.210 |

| 95%CI | [1.8–6.3] | [1.6–3.8] | [2.1–4.2] | ||

| WIS (POD365) | Mean (SD) | 3.2 (3.7) | 2.0 (2.5) | 2.4 (3.0) | 0.173 |

| 95%CI | [1.4–5.1] | [1.2–2.9] | [1.6–3.3] | ||

| Follow up (mo) | Mean (SD) | 75.9 (17.2) | 81.5 (20.5) | 79.6 (19.5) | 0.326 |

| 95%CI | [67.3–84.4] | [74.4–88.5] | [74.2–85.0] |

| Parameters | Statistical Features | Age < 50 yr | Age ≥ 50 yr | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 16 (45.7) | 5 (27.8) | 21 (39.6) | 0.333 |

| Female | 19 (54.3) | 13 (72.2) | 32 (60.4) | ||

| ASA Score | ASA I | 32 (91.4) | 4 (22.2) | 36 (67.9) | <0.001 |

| ASA II | 3 (8.6) | 14 (77.8) | 17 (32.1) | ||

| BMI | Mean (SD) | 27.4 (3.8) | 26.6 (2.9) | 27.1 (3.5) | 0.458 |

| 95%CI | [26.1–28.7] | [25.2–28.1] | [26.1–28.1] | ||

| Hospital Stay | Mean (SD) | 5 (4) | 5 (2) | 5 (4) | 0.707 |

| 95%CI | [4,5,6,7] | [4,5,6] | [4,5,6] | ||

| ODS (Preop) | Mean (SD) | 13.7 (2.9) | 11.1 (3.0) | 12.8 (3.2) | 0.005 |

| 95%CI | [12.7–14.7] | [9.6–12.6] | [11.9–13.7] | ||

| ODS (POD90) | Mean (SD) | 2.5 (2.2) | 2.0 (2.0) | 2.4 (2.1) | 0.377 |

| 95%CI | [1.8–3.3] | [1.0–3.0] | [1.8–2.9] | ||

| ODS (POD180) | Mean (SD) | 4.5 (2.2) | 3.7 (2.3) | 4.2 (2.2) | 0.240 |

| 95%CI | [3.7–5.2] | [2.6–4.9] | [3.6–4.8] | ||

| ODS (POD365) | Mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.8) | 4.2 (2.8) | 5.2 (2.9) | 0.056 |

| 95%CI | [4.8–6.7] | [2.8–5.6] | [4.4–6.0] | ||

| LARS (POD90) | Mean (SD) | 15.8 (13.0) | 22.3 (11.1) | 18.0 (12.7) | 0.078 |

| 95%CI | [11.3–20.3] | [16.8–27.8] | [14.5–21.5] | ||

| LARS (POD180) | Mean (SD) | 7.2 (6.6) | 11.9 (6.2) | 8.8 (6.8) | 0.016 |

| 95%CI | [5.0–9.5] | [8.8–15.0] | [6.9–10.7] | ||

| LARS (POD365) | Mean (SD) | 2.0 (3.0) | 6.6 (4.8) | 3.5 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| 95%CI | [1.0–3.0] | [4.2–8.9] | [2.4–4.7] | ||

| WIS (Preop) | Mean (SD) | 2.5 (2.8) | 6.9 (4.0) | 4.0 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| 95%CI | [1.5–3.4] | [4.9–8.9] | [2.9–5.0] | ||

| WIS (POD90) | Mean (SD) | 5.5 (3.5) | 13.0 (4.2) | 8.1 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| 95%CI | [4.3–6.7] | [10.9–15.1] | [6.6–9.5] | ||

| WIS (POD180) | Mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.8) | 6.4 (4.4) | 3.2 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| 95%CI | [0.8–2.1] | [4.3–8.6] | [2.1–4.2] | ||

| WIS (POD365) | Mean (SD) | 1.0 (1.2) | 5.2 (3.5) | 2.4 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| 95%CI | [0.6–1.5] | [3.4–6.9] | [1.6–3.3] | ||

| Follow up (mo) | Mean (SD) | 77.3 (16.4) | 84.1 (24.2) | 79.6 (19.5) | 0.291 |

| 95%CI | [71.6–82.9] | [72.1–96.2] | [74.2–85.0] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ates, M.; Akbulut, S.; Sahin, E.; Sarici, K.B.; Karabulut, E.; Sanli, M. Laparoscopic Resection Rectopexy with Transanal Specimen Extraction for Complete Rectal Prolapse: Retrospective Cohort Study of Functional Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020718

Ates M, Akbulut S, Sahin E, Sarici KB, Karabulut E, Sanli M. Laparoscopic Resection Rectopexy with Transanal Specimen Extraction for Complete Rectal Prolapse: Retrospective Cohort Study of Functional Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):718. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020718

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtes, Mustafa, Sami Akbulut, Emrah Sahin, Kemal Baris Sarici, Ertugrul Karabulut, and Mukadder Sanli. 2026. "Laparoscopic Resection Rectopexy with Transanal Specimen Extraction for Complete Rectal Prolapse: Retrospective Cohort Study of Functional Outcomes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020718

APA StyleAtes, M., Akbulut, S., Sahin, E., Sarici, K. B., Karabulut, E., & Sanli, M. (2026). Laparoscopic Resection Rectopexy with Transanal Specimen Extraction for Complete Rectal Prolapse: Retrospective Cohort Study of Functional Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020718