Assessing Potential Valve-Preserving Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Degenerative Aortic Stenosis: A Propensity-Matched Study

Highlights

- Among patients with aortic stenosis, is SGLT2 inhibitor therapy associated with differences in key clinical outcomes, including all-cause mortality and progression to aortic valve replacement?

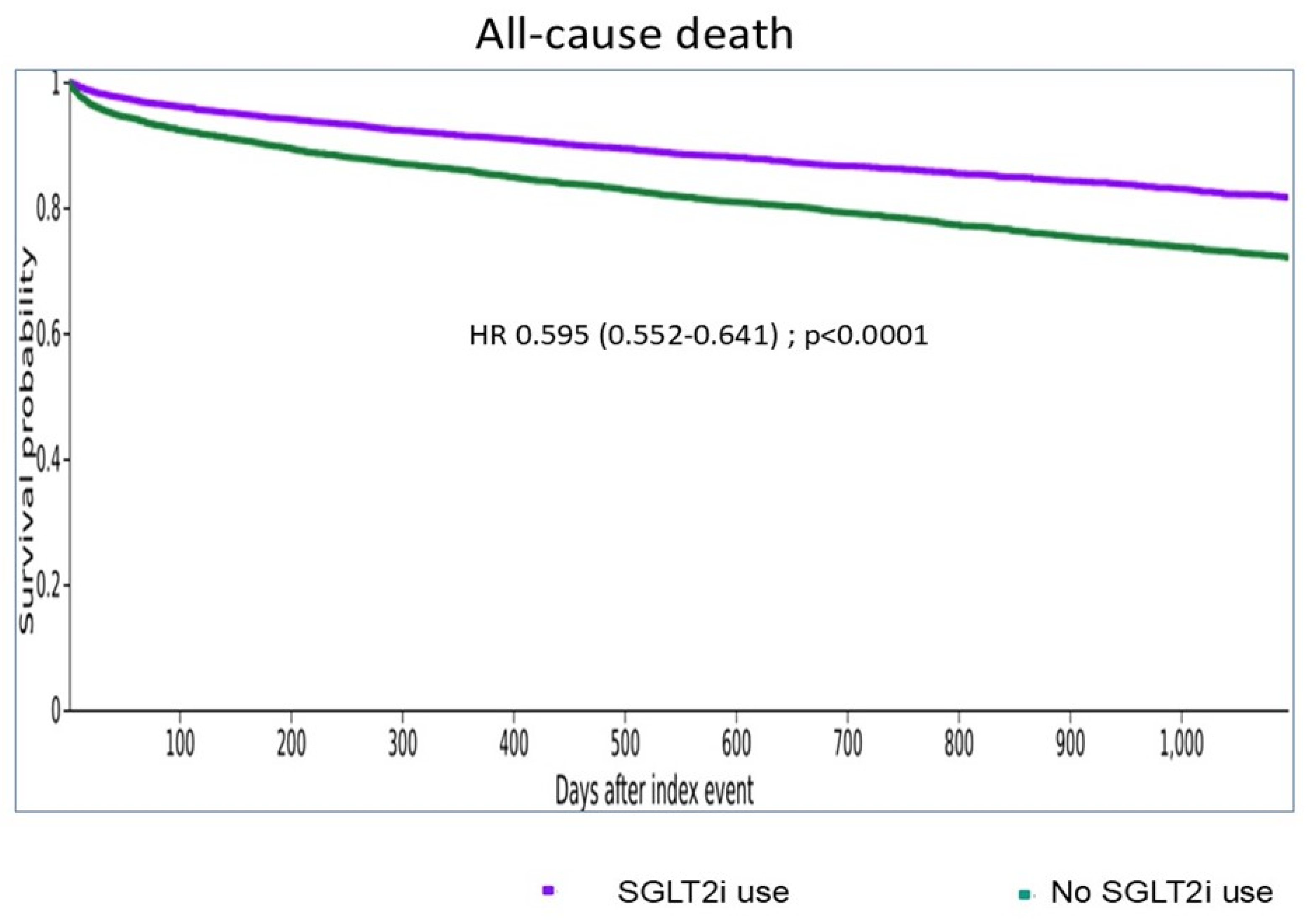

- In patients with aortic stenosis, SGLT2 inhibitor therapy was associated with lower risks of mortality and aortic valve replacement (SAVR or TAVR). These observations raise the possibility of a favorable effect on the clinical trajectory of aortic stenosis; however, the findings should be interpreted as associative given the absence of systematic longitudinal assessment of valvular disease progression.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury (if needed; appears indirectly via kidney outcomes) |

| ARNI | Angiotensin Receptor–Neprilysin Inhibitor |

| AS | Aortic stenosis |

| AT1R | Angiotensin II Type-1 Receptor |

| ATC | Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification |

| AVA | Aortic valve area |

| AVR | Aortic valve replacement |

| BNP | B-type natriuretic peptide |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CM | Clinical Modification (as in ICD-10-CM) |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| DPP-4 | Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 |

| EF | Ejection fraction (used as LVEF) |

| EMR | Electronic medical record |

| ESKD | End-stage kidney disease |

| FXa | Activated factor X |

| GFR | Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| ICD-9/ICD-10-CM | International Classification of Diseases, 9th/10th Revision, Clinical Modification |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| IV | Interventricular |

| LF/LG AS | Low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| MRA | Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist |

| MDRD | Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (formula for GFR) |

| NT-proBNP | N-Terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| PSM | Propensity score matching |

| SAVR | Surgical aortic valve replacement |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SGLT2 | Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 |

| SGLT2i | SGLT2 inhibitor |

| SMD | Standardized mean difference |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TAVR | Transcatheter aortic valve replacement |

| VEC | Valvular endothelial cell |

| Vmax | Peak Aortic Jet Velocity |

| VT/VF | Ventricular Tachycardia/Ventricular Fibrillation |

References

- Usman, M.S.; Siddiqi, T.J.; Anker, S.D.; Bakris, G.L.; Bhatt, D.L.; Filippatos, G.; Fonarow, G.C.; Greene, S.J.; Januzzi, J.L., Jr.; Khan, M.S.; et al. Effect of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Cardiovascular Outcomes Across Various Patient Populations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, L.R. The Pleiotropic Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors: Remodeling the Treatment of Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroueh, A.; Algara-Suarez, P.; Fakih, W.; Gong, D.S.; Matsushita, K.; Park, S.H.; Amissi, S.; Auger, C.; Kauffenstein, G.; Meyer, N.; et al. SGLT2 expression in human vasculature and heart correlates with low-grade inflammation and causes eNOS-NO/ROS imbalance. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 121, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmadeh, S.; Trimaille, A.; Matsushita, K.; Marchandot, B.; Carmona, A.; Zobairi, F.; Sato, C.; Kindo, M.; Hoang, T.M.; Toti, F.; et al. Human Aortic Stenotic Valve-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Induce Endothelial Dysfunction and Thrombogenicity Through AT1R/NADPH Oxidases/SGLT2 Pro-Oxidant Pathway. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci. 2024, 9, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimaille, A.; Hmadeh, S.; Matsushita, K.; Marchandot, B.; Kauffenstein, G.; Morel, O. Aortic stenosis and the haemostatic system. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scisciola, L.; Paolisso, P.; Belmonte, M.; Gallinoro, E.; Delrue, L.; Taktaz, F.; Fontanella, R.A.; Degrieck, I.; Pesapane, A.; Casselman, F.; et al. Myocardial sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 expression and cardiac remodelling in patients with severe aortic stenosis: The BIO-AS study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimaille, A.; Hmadeh, S.; Kikuchi, S.; Mroueh, A.; Carmona, A.; Marchandot, B.; Beras, F.; Truong, D.P.; Vu, M.C.; Granier, A.; et al. Detrimental effects of plasma from patients with severe aortic stenosis on valvular endothelial cells: Role of proinflammatory cytokines and factor Xa. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, e041701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucci, T.; Alam, U.; Fauchier, G.; Lochon, L.; Bisson, A.; Ducluzeau, P.H.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Fauchier, L. GLP-1 receptor agonists and cardiovascular events in metabolically healthy or unhealthy obesity. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 2418–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucci, T.; Gerra, L.; Lam, S.H.M.; Argyris, A.A.; Boriani, G.; Proietti, R.; Bisson, A.; Fauchier, L.; Lip, G.Y.H. Risk of death and thrombosis in patients admitted to the emergency department with supraventricular tachycardias. Heart Rhythm. Off. J. Heart Rhythm. Soc. 2024, 22, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, O.; Granier, A.; Lochon, L.; Trimaille, A.; Bisson, A.; Marchandot, B.; Bernard, A.; Fauchier, L. Association of SGLT2 Inhibitors with Mortality and Bioprosthesis Valve Failure After TAVR: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coisne, A.; Scotti, A.; Latib, A.; Montaigne, D.; Ho, E.C.; Ludwig, S.; Modine, T.; Genereux, P.; Bax, J.J.; Leon, M.B.; et al. Impact of Moderate Aortic Stenosis on Long-Term Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamperidis, V.; Anastasiou, V.; Ziakas, A. Could SGLT2 inhibitors improve outcomes in patients with heart failure and significant valvular heart disease? Need for action. Heart Fail. Rev. 2025, 30, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposeiras-Roubin, S.; Amat-Santos, I.J.; Rossello, X.; Gonzalez Ferreiro, R.; Gonzalez Bermudez, I.; Lopez Otero, D.; Nombela-Franco, L.; Gheorghe, L.; Diez, J.L.; Baladron Zorita, C.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, R.; Sakai, K.; Kameshima, S. Dapagliflozin inhibits TGF-beta-induced transdifferentiation of valvular interstitial cells and mitral valvular degeneration. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 104, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, T.; Zhang, Z.; Shah, H.; Fanaroff, A.C.; Nathan, A.S.; Parise, H.; Lutz, J.; Sugeng, L.; Bellumkonda, L.; Redfors, B.; et al. Effect of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors on the Progression of Aortic Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2025, 18, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, M.T.; Awad, K.; Farina, J.M.; Tamarappoo, B.K.; Lee, K.S.; Lester, S.J.; Alsidawi, S.; Sell-Dottin, K.A.; Ayoub, C.; Arsanjani, R. The Association Between Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors and Bioprosthetic Aortic Valve Degeneration. JACC Adv. 2025, 4, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeidat, O.; Alayyat, A.; Naser, A.; Ghanem, F.; Jabri, A.; Brankovic, M.; Jiao, T.; Ruzieh, M.; Haddad, A.; Alexy, T.; et al. Impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on long-term outcomes in TAVI patients with heart failure: A propensity-matched analysis. Rev. Esp. De Cardiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro Conde, A.; Marzal Martin, D.; Campuzano Ruiz, R.; Fernandez Olmo, M.R.; Morillas Arino, C.; Gomez Doblas, J.J.; Gorriz Teruel, J.L.; Mazon Ramos, P.; Garcia-Moll Marimon, X.; Soler Romeo, M.J.; et al. Comprehensive Cardiovascular and Renal Protection in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goes-Santos, B.R.; Castro, P.C.; Girardi, A.C.C.; Antunes-Correa, L.M.; Davel, A.P. Vascular effects of SGLT2 inhibitors: Evidence and mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2025, 329, C1150–C1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| AS, SGLT2 Inhibitors | AS, No SGLT2 Inhibitors | Std Diff. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 10,912) | (n = 10,912) | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 73.4 +/− 11.6 | 73.6 +/− 11.5 | 1.8 |

| Men, n (%) | 5933 (54.4%) | 5947 (54.5%) | 0.3 |

| White, n (%) | 7069 (64.8%) | 7031 (64.4%) | 0.7 |

| Black or African American, n (%) | 941 (8.6%) | 938 (8.6%) | 0.1 |

| Socioeconomic and psychosocial circumstances, n (%) | 224 (2.1%) | 210 (1.9%) | 0.9 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 7116 (65.2%) | 7029 (64.4%) | 1.7 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 5631 (51.6%) | 5786 (53%) | 2.8 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 1688 (15.5%) | 1685 (15.4%) | 0.1 |

| Overweight or obesity, n (%) | 2378 (21.8%) | 2405 (22%) | 0.6 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 6621 (60.7%) | 6598 (60.5%) | 0.4 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | |||

| Heart failure, n (%) | 4731 (43.4%) | 4724 (43.3%) | 0.1 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 4759 (43.6%) | 4775 (43.8%) | 0.3 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 1127 (10.3%) | 1116 (10.2%) | 0.3 |

| Ischemic stroke, n (%) | 548 (5%) | 558 (5.1%) | 0.4 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter, n (%) | 3182 (29.2%) | 3260 (29.9%) | 1.6 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 816 (7.5%) | 820 (7.5%) | 0.1 |

| Non-cardiovascular comorbidities | |||

| Kidney disease, n (%) | 3422 (31.4%) | 3406 (31.2%) | 0.3 |

| COPD, n (%) | 1271 (11.6%) | 1293 (11.8%) | 0.6 |

| Sleep apnea syndrome, n (%) | 1579 (14.5%) | 1561 (14.3%) | 0.5 |

| Previous cancer, n (%) | 2192 (20.1%) | 2157 (19.8%) | 0.8 |

| Cognitive impairment, n (%) | 93 (0.9%) | 81 (0.7%) | 1.2 |

| Laboratory tests and examinations | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 30.6 +/− 7.6 | 30.5 +/− 7.5 | 0.2 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 155.5 +/− 47.0 | 157.8 +/− 45.5 | 5 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 83.2 +/− 36.5 | 86.4 +/− 34.8 | 9 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 46.1 +/− 17.8 | 46.6 +/− 17.4 | 3.1 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 138.7 +/− 98.2 | 132.4 +/− 91.1 | 6.7 |

| HbA1c ≥ 6%, n (%) | 3058 (28%) | 2961 (27.1%) | 2 |

| Estimated GFR (MDRD, ml/min), mean ± SD | 62.3 +/− 25.7 | 60.3 +/− 27.2 | 7.6 |

| BNP, ng/L, mean ± SD | 1259.4 +/− 3194.1 | 1056.7 +/− 2706.7 | 6.8 |

| NT-proBNP, ng/L, mean ± SD | 4869.7 +/− 8035.9 | 5223.1 +/− 8777.1 | 4.2 |

| LVEF, mean ± SD | 54.9 +/− 14.5 | 54.1 +/− 16.0 | 5.3 |

| Medications | |||

| Beta blockers, n (%) | 6341 (58.1%) | 6386 (58.5%) | 0.8 |

| Calcium channel blockers, n (%) | 3845 (35.2%) | 3807 (34.9%) | 0.7 |

| ACE Inhibitors, n (%) | 3038 (27.8%) | 3027 (27.7%) | 0.2 |

| Angiotensin II Inhibitors, n (%) | 3264 (29.9%) | 3246 (29.7%) | 0.4 |

| ARNI, n (%) | 327 (3%) | 315 (2.9%) | 0.7 |

| MRA, n (%) | 1614 (14.8%) | 1639 (15%) | 0.6 |

| Digitalis glycosides, n (%) | 402 (3.7%) | 404 (3.7%) | 0.1 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 6306 (57.8%) | 6367 (58.3%) | 1.1 |

| Lipid lowering drugs, n (%) | 7200 (66%) | 7228 (66.2%) | 0.5 |

| Insulin, n (%) | 2893 (26.5%) | 2889 (26.5%) | 0.1 |

| Metformin, n (%) | 2711 (24.8%) | 2794 (25.6%) | 1.8 |

| Sulfonylureas, n (%) | 1323 (12.1%) | 1344 (12.3%) | 0.6 |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists, n (%) | 402 (3.7%) | 385 (3.5%) | 0.8 |

| DPP4 inhibitors, n (%) | 882 (8.1%) | 889 (8.1%) | 0.2 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors, n (%) | 10,912 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| Thiazolidinediones, n (%) | 230 (2.1%) | 261 (2.4%) | 1.9 |

| Antiplatelet therapy, n (%) | 5180 (47.5%) | 5238 (48%) | 1.1 |

| Anticoagulant, n (%) | 1376 (12.6%) | 1419 (13%) | 1.2 |

| Clinical Outcomes (Median FU 1.22, IQR 2.32) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Events (Yearly Rate, %) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| Death | 1045 (6.15) | 2084 (9.34) | 0.595 (0.552–0.641) | <0.0001 |

| SAVR | 251 (1.28) | 499 (1.90) | 0.514 (0.442–0.599) | <0.0001 |

| TAVR | 554 (2.81) | 698 (2.89) | 0.835 (0.746–0.934) | 0.002 |

| Ischemic stroke or thromboembolism | 328 (2.25) | 430 (2.29) | 0.914 (0.791–1.056) | 0.22 |

| Acute MI | 152 (0.84) | 205 (0.87) | 0.822 (0.666–1.015) | 0.07 |

| Incident HF | 1138 (10.38) | 1256 (9.64) | 1.023 (0.943–1.108) | 0.59 |

| Hospitalization for HF | 970 (4.01) | 706 (2.76) | 1.436 (1.303–1.582) | <0.0001 |

| Incident AF | 896 (6.97) | 1087 (7.03) | 0.918 (0.840–1.003) | 0.06 |

| Cardiac arrest | 159 (0.82) | 255 (1.21) | 0.71 (0.582–0.867) | 0.001 |

| VT/VF | 485 (2.68) | 529 (2.37) | 1.02 (0.901–1.155) | 0.75 |

| ESKD | 66 (0.40) | 243 (1.00) | 0.292 (0.222–0.384) | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Morel, O.; Guglieri, M.; Trimaille, A.; Marchandot, B.; Bisson, A.; Granier, A.; Schini-Kerth, V.; Bernard, A.; Fauchier, L. Assessing Potential Valve-Preserving Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Degenerative Aortic Stenosis: A Propensity-Matched Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020714

Morel O, Guglieri M, Trimaille A, Marchandot B, Bisson A, Granier A, Schini-Kerth V, Bernard A, Fauchier L. Assessing Potential Valve-Preserving Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Degenerative Aortic Stenosis: A Propensity-Matched Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):714. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020714

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorel, Olivier, Michael Guglieri, Antonin Trimaille, Benjamin Marchandot, Arnaud Bisson, Amandine Granier, Valérie Schini-Kerth, Anne Bernard, and Laurent Fauchier. 2026. "Assessing Potential Valve-Preserving Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Degenerative Aortic Stenosis: A Propensity-Matched Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020714

APA StyleMorel, O., Guglieri, M., Trimaille, A., Marchandot, B., Bisson, A., Granier, A., Schini-Kerth, V., Bernard, A., & Fauchier, L. (2026). Assessing Potential Valve-Preserving Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Degenerative Aortic Stenosis: A Propensity-Matched Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020714