Magnetic Resonance-Based Determination of Local Tissue Infection Involvement in Patients with Periprosthetic Joint Infection Following Total Hip Arthroplasty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

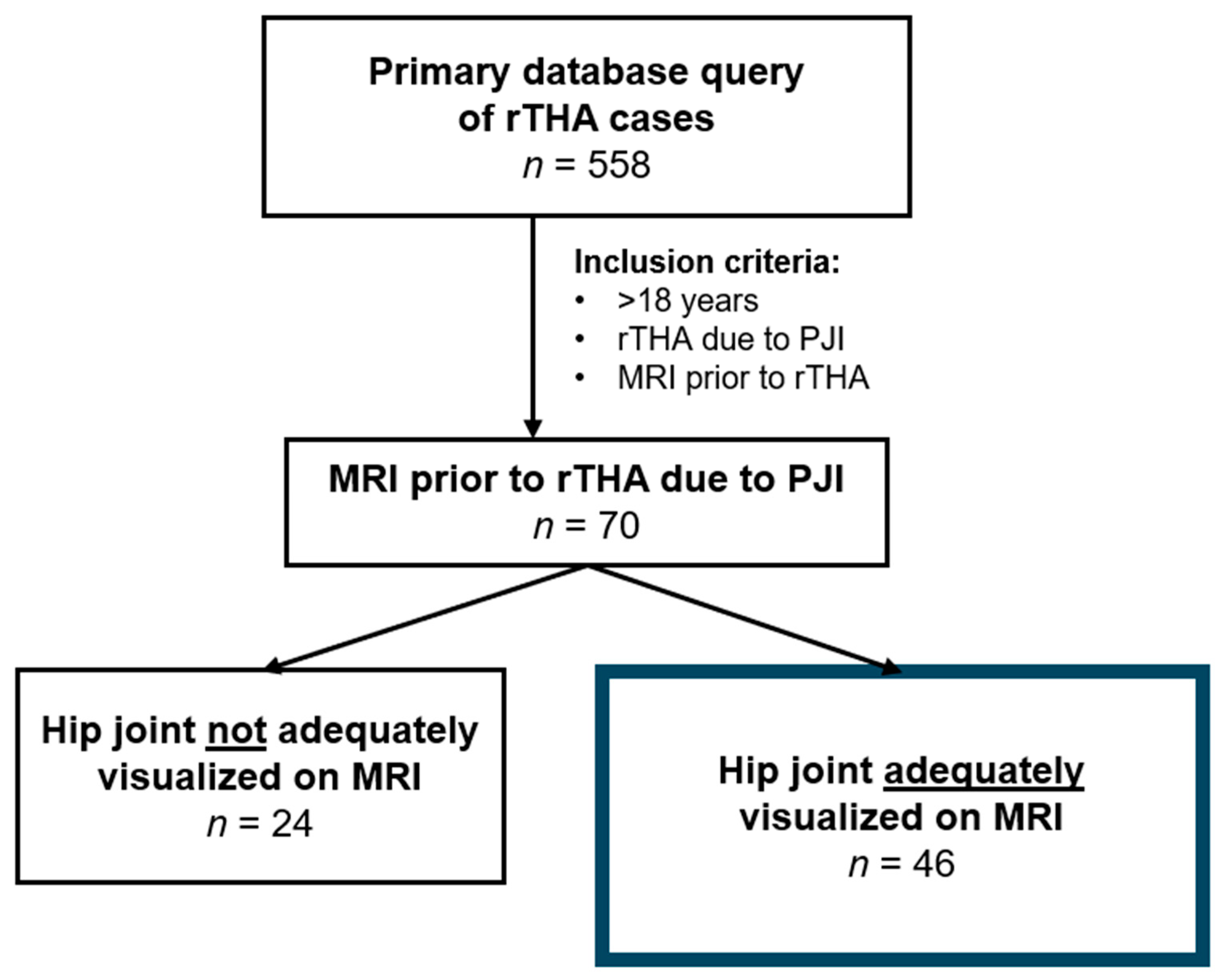

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Imaging Protocol

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

3.2. Operative Characteristics

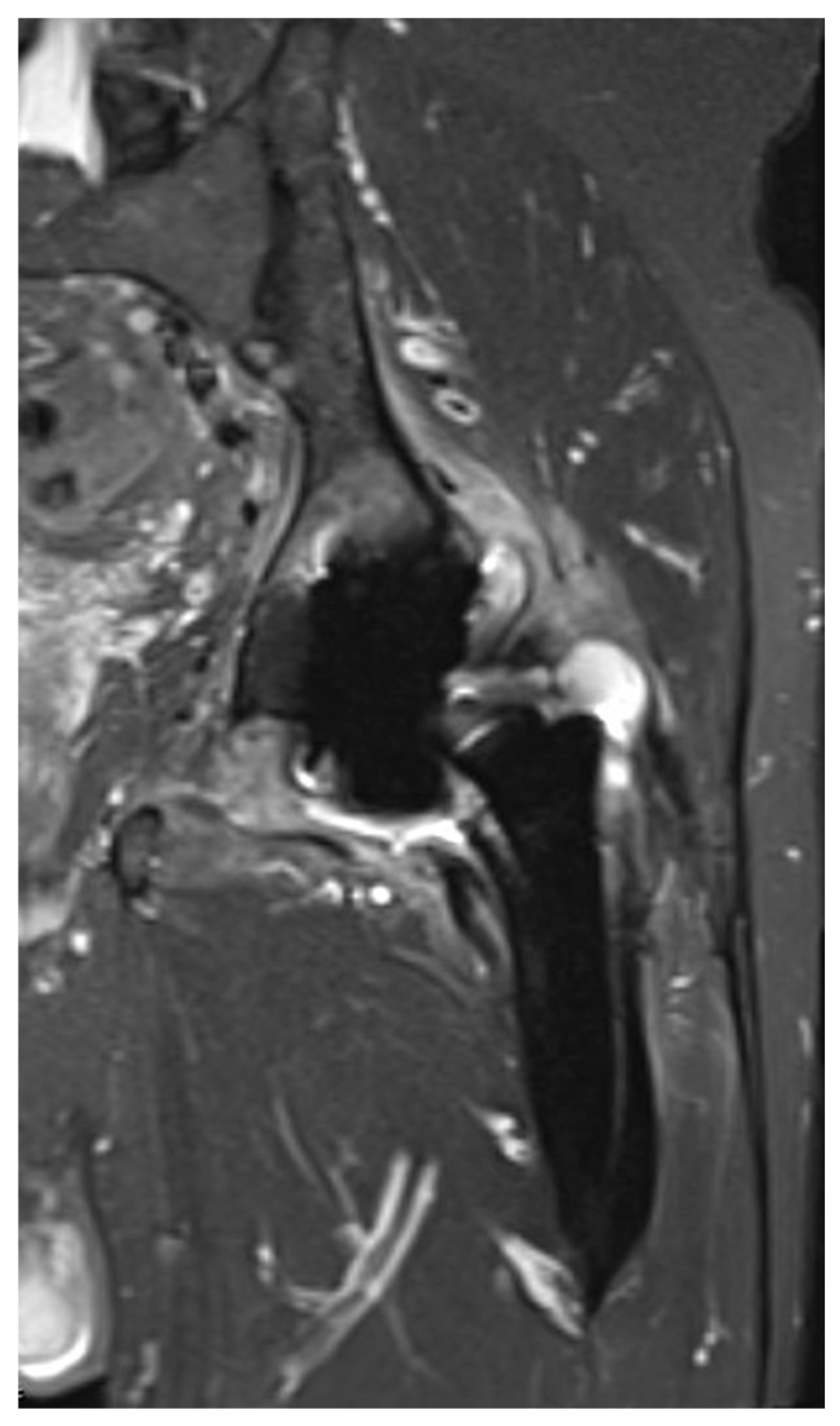

3.3. Imaging Findings

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Triantafyllopoulos, G.K.; Soranoglou, V.G.; Memtsoudis, S.G.; Sculco, T.P.; Poultsides, L.A. Rate and Risk Factors for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Among 36,494 Primary Total Hip Arthroplasties. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMaster Arthroplasty Collaborative (MAC). Risk Factors for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Following Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: A 15-Year, Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2020, 102, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.L.; Kurtz, S.M.; Lau, E.; Bozic, K.J.; Berry, D.J.; Parvizi, J. Prosthetic joint infection risk after total hip arthroplasty in the Medicare population. J. Arthroplast. 2009, 24, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, A.; Kolin, D.A.; Farley, K.X.; Wilson, J.M.; McLawhorn, A.S.; Cross, M.B.; Sculco, P.K. Projected Economic Burden of Periprosthetic Joint Infection of the Hip and Knee in the United States. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 1484–1489.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, J.; Tan, T.L.; Goswami, K.; Higuera, C.; Della Valle, C.; Chen, A.F.; Shohat, N. The 2018 Definition of Periprosthetic Hip and Knee Infection: An Evidence-Based and Validated Criteria. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 1309–1314.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, A.L.; DeSimone, C.A.; Lowenstein, N.A.; Deirmengian, C.; Fillingham, Y.A. Discrepancies in Periprosthetic Joint Infection Diagnostic Criteria Reporting and Use: A Scoping Review and Call for a Standard Reporting Framework. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2025, 483, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschke, E.; Kluge, T.; Stallkamp, F.; Roth, A.; Zajonz, D.; Hoffmann, K.T.; Sabri, O.; Kluge, R.; Ghanem, M. Use of PET-CT in diagnostic workup of periprosthetic infection of hip and knee joints: Significance in detecting additional infectious focus. Int. Orthop. 2022, 46, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoveidaei, A.; Tavakoli, Y.; Ramezanpour, M.R.; Omouri-Kharashtomi, M.; Taghavi, S.P.; Hoveidaei, A.H.; Conway, J.D. Imaging in Periprosthetic Joint Infection Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review. Microorganisms 2024, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galley, J.; Sutter, R.; Stern, C.; Filli, L.; Rahm, S.; Pfirrmann, C.W.A. Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Hip Joint Infection Using MRI with Metal Artifact Reduction at 1.5 T. Radiology 2020, 296, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwaiger, B.J.; Gassert, F.T.; Suren, C.; Gersing, A.S.; Haller, B.; Pfeiffer, D.; Dangelmaier-Dawirs, J.; Roski, F.; von Eisenhart-Rothe, R.; Prodinger, P.M.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI with metal artifact reduction for the detection of periprosthetic joint infection and aseptic loosening of total hip arthroplasty. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 131, 109253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, B.N.; Palestro, C.J.; Fox, M.G.; Bell, A.M.; Blankenbaker, D.G.; Frick, M.A.; Jawetz, S.T.; Kuo, P.H.; Said, N.; Stensby, J.D.; et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Imaging After Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2023, 20, S413–S432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, D.; Messina, C.; Zagra, L.; Andreata, M.; De Vecchi, E.; Gitto, S.; Sconfienza, L.M. Failed Total Hip Arthroplasty: Diagnostic Performance of Conventional MRI Features and Locoregional Lymphadenopathy to Identify Infected Implants. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2021, 53, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanò, C.L.; Petrosillo, N.; Argento, G.; Sconfienza, L.M.; Treglia, G.; Alavi, A.; Glaudemans, A.; Gheysens, O.; Maes, A.; Lauri, C.; et al. The Role of Imaging Techniques to Define a Peri-Prosthetic Hip and Knee Joint Infection: Multidisciplinary Consensus Statements. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shufen, C.; Jinmin, L.; Xiaohui, Z.; Bin, G. Diagnostic value of magnetic resonance imaging for patients with periprosthetic joint infection: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, A.; Jäger, M.; Beck, S.; Wegner, A.; Portegys, E.; Wassenaar, D.; Theysohn, J.; Haubold, J. Metal Artefact Reduction Sequences (MARS) in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) after Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA): A non-invasive approach for preoperative differentiation between periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) and aseptic complications? BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plodkowski, A.J.; Hayter, C.L.; Miller, T.T.; Nguyen, J.T.; Potter, H.G. Lamellated Hyperintense Synovitis: Potential MR Imaging Sign of an Infected Knee Arthroplasty. Radiology 2013, 266, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Lim, D.; Kim, E.; Kim, S.; Song, H.-T.; Suh, J.-S. Usefulness of slice encoding for metal artifact correction (SEMAC) for reducing metallic artifacts in 3-T MRI. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2013, 31, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, Y.; Ding, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Tu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Fang, X. Metal Artifact Reduction Sequences MRI: A Useful Reference for Preoperative Diagnosis and Debridement Planning of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Parvizi, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Zijlstra, W.P.; Tarabichi, S. Editorial: Management of PJI/SSI after joint arthroplasty. Arthroplasty 2024, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, H.; Zhou, Y. Management of soft tissues in patients with periprosthetic joint infection. Arthroplasty 2023, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R. Periprosthetic Joint Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basinger, H.; Hogg, J.P. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Femoral Triangle. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dauchy, F.A.; Dupon, M.; Dutronc, H.; de Barbeyrac, B.; Lawson-Ayayi, S.; Dubuisson, V.; Souillac, V. Association between psoas abscess and prosthetic hip infection: A case-control study. Acta Orthop. 2009, 80, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaratne, G.D.; Khan, R.J.; Tan, C.; Golledge, C. Bilateral prosthetic hip joint infections associated with a Psoas abscess. A Case Report. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2016, 6, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Charalampopoulos, A.; Macheras, A.; Charalabopoulos, A.; Fotiadis, C.; Charalabopoulos, K. Iliopsoas abscesses: Diagnostic, aetiologic and therapeutic approach in five patients with a literature review. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 44, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jesus Lopes Filho, G.; Matone, J.; Arasaki, C.H.; Kim, S.B.; Mansur, N.S. Psoas abscess: Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations in six patients. Int. Surg. 2000, 85, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stone, A.H.; King, P.J. Simultaneous combined retroperitoneal and posterior hip approach for the treatment of iliopsoas abscess with extension to a metal-on-metal prosthetic hip joint. Arthroplast. Today 2019, 5, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laratta, J.L.; Davis, E.G.; Glassman, S.D.; Dimar, J.R. The transperitoneal approach for anterior lumbar interbody fusion at L5-S1: A technical note. J. Spine Surg. 2018, 4, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberoğlu, M.; Uz, A.; Ozmen, M.M.; Bozkurt, M.C.; Erkuran, C.; Taner, S.; Tekin, A.; Tekdemir, I. Corona mortis: An anatomic study in seven cadavers and an endoscopic study in 28 patients. Surg. Endosc. 2001, 15, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, D.C.; Graney, D.O.; Routt, M.L., Jr. Retropubic vascular hazards of the ilioinguinal exposure: A cadaveric and clinical study. J. Orthop. Trauma 1996, 10, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakurt, L.; Karaca, I.; Yilmaz, E.; Burma, O.; Serin, E. Corona mortis: Incidence and location. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2002, 122, 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menge, T.J.; Cole, H.A.; Mignemi, M.E.; Corn, W.C.; Martus, J.E.; Lovejoy, S.A.; Stutz, C.M.; Mencio, G.A.; Schoenecker, J.G. Medial approach for drainage of the obturator musculature in children. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2014, 34, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, D.R.; Heller, K.D. Hip Abductor Deficiency after Total Hip Arthroplasty: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Methods. Z. Orthop. Unfall. 2023, 161, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.H.; Kim, E.H.; Song, H.S.; Cha, J.G. A case of primary psoas abscess presenting as buttock abscess. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2009, 10, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, H.L.T.; Ang, K.X.M.; Loh, S.Y.J. A reproducible reference point for the common peroneal nerve during surgery at the posterolateral corner of the knee: A cadaveric study. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2020, 32, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, S.; Nimura, A.; Ibara, T.; Chikazawa, K.; Nakazawa, M.; Akita, K. Anatomical basis for contribution of hip joint motion by the obturator internus to defaecation/urinary functions by the levator ani via the obturator fascia. J. Anat. 2023, 242, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteside, L.A. Surgical technique: Transfer of the anterior portion of the gluteus maximus muscle for abductor deficiency of the hip. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2012, 470, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, D.M.; Bornes, T.D.; Al Khalifa, A.; Kuzyk, P.; Gross, A.; Safir, O. Surgical Technique: Abductor Reconstruction With Gluteus Maximus and Tensor Fascia Lata in Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2022, 37, S628–S635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, E.J.; Woodson, C.; Holtom, P.; Roidis, N.; Shufelt, C.; Patzakis, M. Periprosthetic total hip infection: Outcomes using a staging system. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2002, 403, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, J.Y. Specificities of total hip and knee arthroplasty revision for infection. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2020, 106, S27–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, A.L.; Kildow, B.J.; Cortés-Penfield, N.W. Periprosthetic Joint Infections. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 39, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberne, S.J.; Raijmakers, P.G.; Temmerman, O.P. The Accuracy of Imaging Techniques in the Assessment of Periprosthetic Hip Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2016, 98, 1638–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardon, M.; Fritz, J.; Samim, M. Imaging approach to prosthetic joint infection. Skelet. Radiol. 2024, 53, 2023–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.H.; He, C.; Feng, J.M.; Li, Z.H.; Chen, Z.; Yan, F.H.; Lu, Y. Magnetic resonance imaging parameter optimizations for diagnosis of periprosthetic infection and tumor recurrence in artificial joint replacement patients. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartz, A.; Marsh, J.L. Methodologic issues in observational studies. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2003, 413, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunovic, N.; Sprague, S.; Bhandari, M. Methodological issues in systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies in orthopaedic research. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2009, 91, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.M.; Binnicker, M.J.; Campbell, S.; Carroll, K.C.; Chapin, K.C.; Gonzalez, M.D.; Harrington, A.; Jerris, R.C.; Kehl, S.C.; Leal, S.M., Jr.; et al. Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2024 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Cohort (n = 46) |

|---|---|

| Mean age at surgery ± SD [range], (years) | 64.3 ± 9.9 [33–81] |

| Mean BMI ± SD [range], (kg/m2) | 31.7 ± 6.7 [17.7–44.3] |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 21 (45.7) |

| Male | 25 (54.3) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 34 (73.9) |

| Black or African American | 7 (15.2) |

| Hispanic | 2 (4.3) |

| Other | 3 (6.5) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Never | 23 (50.0) |

| Former | 19 (41.3) |

| Current | 4 (8.7) |

| ASA score, n (%) | |

| I | 0 (0.0) |

| II | 24 (52.2) |

| III | 21 (45.7) |

| IV | 1 (2.2) |

| Anesthesia type, n (%) | |

| General | 31 (67.4) |

| Spinal | 15 (32.6) |

| Mean CCI ± SD | 3.5 ± 2.0 |

| Mean length of stay ± SD, (days) | 7.3 ± 6.6 |

| Mean length of follow-up ± SD, (months) | 25.3 ± 25.4 |

| Parameter | Cohort (n = 46) |

|---|---|

| Indication for rTHA, n (%) | |

| Acute PJI | 23 (50.0) |

| Chronic PJI | 20 (43.5) |

| Unknown | 3 (6.5) |

| Growth of cultures, n (%) | |

| MSSA | 22 (47.8) |

| Escherichia coli | 3 (6.5) |

| Morganella morganii | 1 (2.2) |

| MRSA | 3 (6.5) |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 2 (4.3) |

| Abiotrophia defectiva | 1 (2.2) |

| Candida species | 1 (2.2) |

| Culture-negative | 13 (28.3) |

| Treatment, n (%) | |

| DAIR | 24 (52.2) |

| Two-stage revision arthroplasty | 22 (47.8) |

| Surgical approach, n (%) | |

| Anterior-based | 3 (6.5) |

| Lateral-based | 2 (4.3) |

| Posterior-based | 41 (89.1) |

| Single or dual incisions, n (%) | |

| Single | 37 (80.4) |

| Dual | 9 (19.6) |

| Failure of treatment, n (%) | 13 (28.3) |

| Treatment following failure, n (%) | |

| DAIR | 2 (15.4) |

| One-stage revision arthroplasty | 2 (15.4) |

| Two-stage revision arthroplasty | 9 (69.2) |

| Surgical approach following treatment failure, n (%) | |

| Anterior based | 1 (7.7) |

| Lateral based | 2 (15.4) |

| Posterior based | 10 (76.9) |

| Parameter | Cohort (n = 46) |

|---|---|

| Any pathological finding, n (%) | 45 (97.8) |

| Location | |

| Anterolateral musculature | 6 (13.0) |

| Greater trochanter | 11 (23.9) |

| Iliotibial band | 2 (4.3) |

| Gluteal muscles | 4 (8.7) |

| Iliopsoas muscle | 8 (17.4) |

| Obturator muscles | 4 (8.7) |

| Sacroiliac joint | 1 (2.2) |

| Soft tissue and musculature adjacent to hip joint | 7 (15.2) |

| Joint effusion, n (%) | 34 (73.9) |

| Amount | |

| Small | 4 (8.7) |

| Moderate | 22 (47.8) |

| Large | 8 (17.4) |

| Location extension | 30 (65.2) |

| Anterolateral musculature | 6 (13.0) |

| Greater trochanter | 8 (17.4) |

| Iliotibial band | 2 (4.3) |

| Gluteal muscles | 4 (8.7) |

| Iliopsoas muscle | 7 (15.2) |

| Obturator muscles | 4 (8.7) |

| Surrounding soft tissue and musculature | 5 (10.8) |

| No joint effusion, n (%) | 12 (26.1) |

| Pathological finding | |

| Sinus tract | 5 (10.8) |

| Osteomyelitis | 1 (2.2) |

| Edematous changes | |

| Greater trochanter | 3 (6.5) |

| Iliopsoas | 1 (2.2) |

| Sacroiliac joint | 1 (2.2) |

| Soft tissue and musculature adjacent to hip joint | 2 (4.3) |

| Capsule thickening, n (%) | 11 (23.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Khury, F.; Ehlers, M.; Kurapatti, M.; Sarfraz, A.; Aggarwal, V.K.; Schwarzkopf, R. Magnetic Resonance-Based Determination of Local Tissue Infection Involvement in Patients with Periprosthetic Joint Infection Following Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020480

Khury F, Ehlers M, Kurapatti M, Sarfraz A, Aggarwal VK, Schwarzkopf R. Magnetic Resonance-Based Determination of Local Tissue Infection Involvement in Patients with Periprosthetic Joint Infection Following Total Hip Arthroplasty. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020480

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhury, Farouk, Mallory Ehlers, Mark Kurapatti, Anzar Sarfraz, Vinay K. Aggarwal, and Ran Schwarzkopf. 2026. "Magnetic Resonance-Based Determination of Local Tissue Infection Involvement in Patients with Periprosthetic Joint Infection Following Total Hip Arthroplasty" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020480

APA StyleKhury, F., Ehlers, M., Kurapatti, M., Sarfraz, A., Aggarwal, V. K., & Schwarzkopf, R. (2026). Magnetic Resonance-Based Determination of Local Tissue Infection Involvement in Patients with Periprosthetic Joint Infection Following Total Hip Arthroplasty. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020480