Analysis of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and High-Fat Feeding Reveals Hepatic Transcriptome Reprogramming: Ironing out the Details

Highlights

- RYGB alters liver genes, reversing obesity-linked transcriptional changes.

- HFD after RYGB triggers liver stress, inflammation, and iron imbalance.

- Diet quality post-RYGB is key to sustaining liver and metabolic benefits.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental Design, Sample Collection and Preparation

2.2. RNA Sequencing and Library Preparation

2.3. Data Processing

2.4. Differential Expression Analysis

- Sham Chow vs. RYGB Chow;

- Sham HFD vs. RYGB HFD;

- RYGB Chow vs. RYGB HFD;

- Sham Chow vs. Sham HFD.

2.5. Identification of Commonly Regulated Genes

2.6. Permutation Analysis for Validation

2.7. Refinement of RYGB-Specific HFD Effects

2.8. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.9. PubMed Gene Association Analysis

2.10. Heatmap Generation

3. Data Availability

4. Results

4.1. Distinct Transcriptomic Landscapes Shaped by Surgical Intervention and Dietary Composition

4.2. RYGB-Driven Hepatic Transcriptomic Remodeling: Enhanced Extracellular/Adipogenesis Pathways and Reduced Metabolic Activity

4.3. Counteracting Obesity-Linked Dysregulation: RYGB-Mediated Reversal of DIO-Associated Gene Signatures

4.4. High-Fat Diet-Driven Hepatic Transcriptomic Reprogramming: Amplified Stress Response and Repressed Protein Synthesis

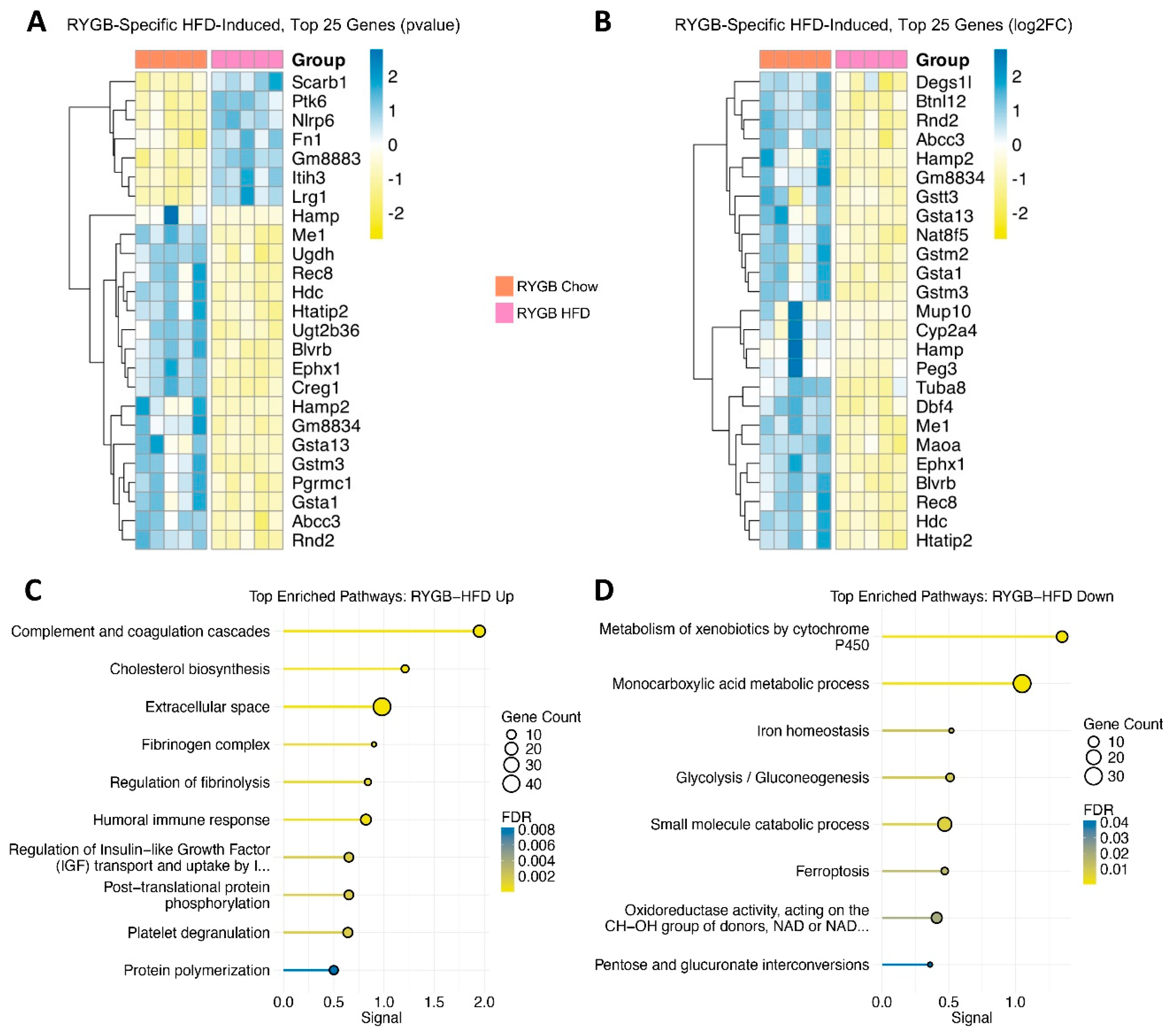

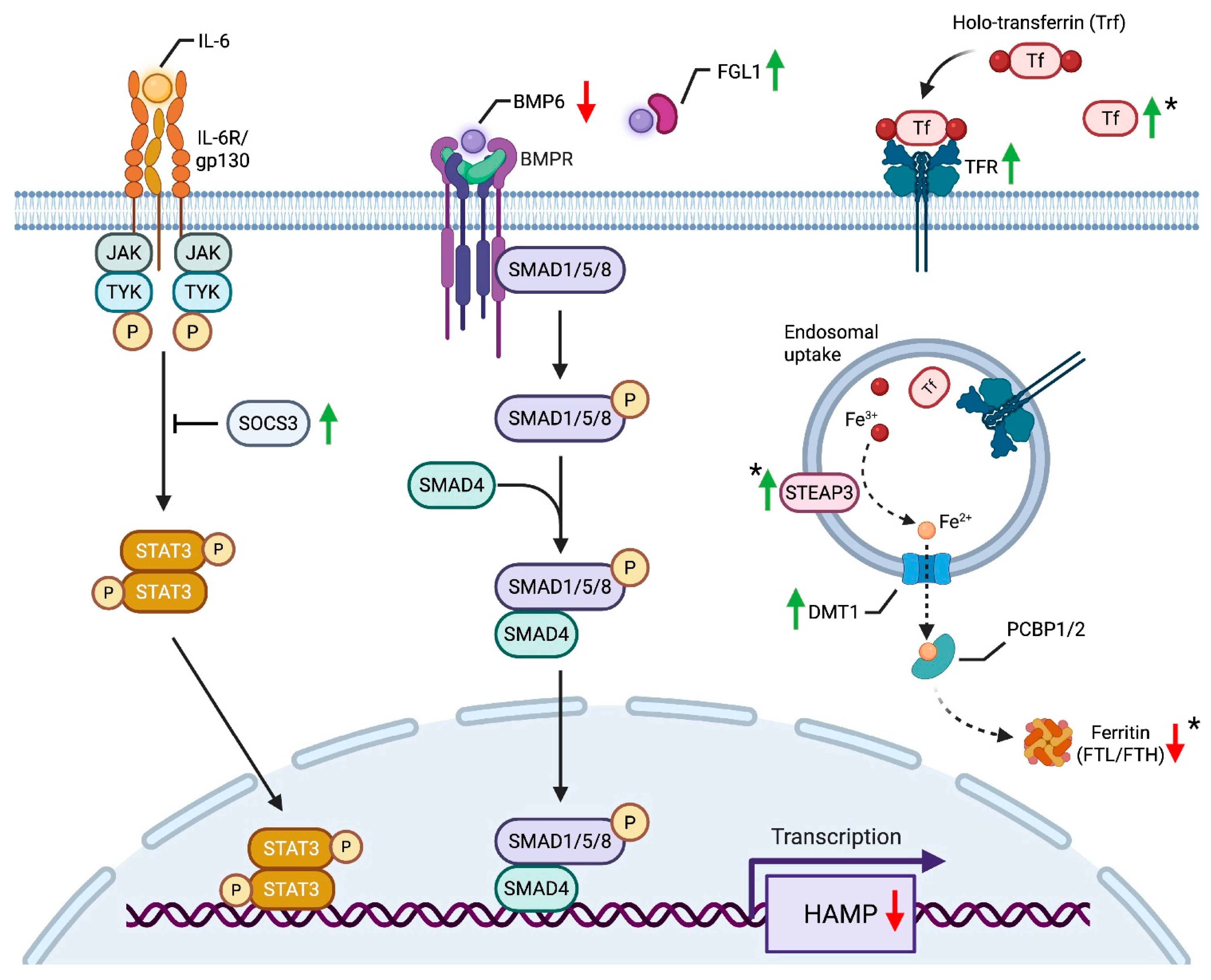

4.5. Residual High-Fat Burden in RYGB: Coagulatory Strain, Inflammatory Pressure, and Impaired Detoxification

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blüher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingvay, I.; Cohen, R.V.; le Roux, C.W.; Sumithran, P. Obesity in adults. Lancet 2024, 404, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeland, I.J.; Lim, S.; Tchernof, A.; Gastaldelli, A.; Rangaswami, J.; Ndumele, C.E.; Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Després, J.-P. Metabolic syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Quek, J.; Chan, K.E.; Wong, Z.Y.; Tan, C.; Tan, B.; Lim, W.H.; Tan, D.J.H.; Tang, A.S.P.; Tay, P.; Xiao, J.; et al. Global prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in the overweight and obese population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, M.; Srivastava, A.; Nacher, M.; Hall, C.; Palaia, T.; Lee, J.; Zhao, C.L.; Lau, R.; Ali, M.A.E.; Park, C.Y.; et al. The Effect of Diet Composition on the Post-operative Outcomes of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass in Mice. Obes. Surg. 2024, 34, 911–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhry, T.K.; Mhaskar, R.; Schwitalla, T.; Muradova, E.; Gonzalvo, J.P.; Murr, M.M. Bariatric surgery improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A contemporary systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefere, S.; Onghena, L.; Vanlander, A.; van Nieuwenhove, Y.; Devisscher, L.; Geerts, A. Bariatric surgery and the liver-Mechanisms, benefits, and risks. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Doumouras, A.G.; Yu, J.; Brar, K.; Banfield, L.; Gmora, S.; Anvari, M.; Hong, D. Complete Resolution of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease After Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 1040–1060.e11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sandvik, E.C.S.; Aasarød, K.M.; Johnsen, G.; Hoff, D.A.L.; Kulseng, B.; Hyldmo, Å.A.; Græslie, H.; Nymo, S.; Sandvik, J.; Fossmark, R. The Effect of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Fibrosis Assessed by FIB-4 and NFS Scores-An 11.6-Year Follow-Up Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4910. [Google Scholar]

- Głuszyńska, P.; Lemancewicz, D.; Dzięcioł, J.B.; Razak Hady, H. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery as Its Treatment Option: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5721. [Google Scholar]

- Khare, T.; Liu, K.; Chilambe, L.O.; Khare, S. NAFLD and NAFLD Related HCC: Emerging Treatments and Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkhomchuk, D.; Borodina, T.; Amstislavskiy, V.; Banaru, M.; Hallen, L.; Krobitsch, S.; Lehrach, H.; Soldatov, A. Transcriptome analysis by strand-specific sequencing of complementary DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; RStudio, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, A.; Ibrahim, J.G.; Love, M.I. Heavy-tailed prior distributions for sequence count data: Removing the noise and preserving large differences. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemerik, J.; Solari, A.; Goeman, J.J. Permutation-based simultaneous confidence bounds for the false discovery proportion. Biometrika 2019, 106, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Wang, X.; Xiao, G. A permutation-based non-parametric analysis of CRISPR screen data. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 545. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.; Fang, Z.; Hua, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, E.; Cowley, A.W.; Liang, M.; Liu, P.; Lu, Y. deGPS is a powerful tool for detecting differential expression in RNA-sequencing studies. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enjalbert-Courrech, N.; Neuvial, P. Powerful and interpretable control of false discoveries in two-group differential expression studies. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 5214–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgrebe, J.; Wurst, W.; Welzl, G. Permutation-validated principal components analysis of microarray data. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, RESEARCH0019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Morris, J.H.; Cook, H.; Kuhn, M.; Wyder, S.; Simonovic, M.; Santos, A.; Doncheva, N.T.; Roth, A.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING database in 2017: Quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D362–D368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Franceschini, A.; Wyder, S.; Forslund, K.; Heller, D.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Santos, A.; Tsafou, K.P.; et al. STRING v10: Protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D447–D452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, A.; Lin, J.; von Mering, C.; Jensen, L.J. SVD-phy: Improved prediction of protein functional associations through singular value decomposition of phylogenetic profiles. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1085–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschini, A.; Szklarczyk, D.; Frankild, S.; Kuhn, M.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Lin, J.; Minguez, P.; Bork, P.; von Mering, C.; et al. STRING v9.1: Protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D808–D815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Franceschini, A.; Kuhn, M.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Minguez, P.; Doerks, T.; Stark, M.; Muller, J.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING database in 2011: Functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D561–D568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.J.; Kuhn, M.; Stark, M.; Chaffron, S.; Creevey, C.; Muller, J.; Doerks, T.; Julien, P.; Roth, A.; Simonovic, M.; et al. STRING 8—A global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D412–D416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mering, C.; Jensen, L.J.; Kuhn, M.; Chaffron, S.; Doerks, T.; Krüger, B.; Snel, B.; Bork, P. STRING 7—Recent developments in the integration and prediction of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D358–D362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mering, C.; Jensen, L.J.; Snel, B.; Hooper, S.D.; Krupp, M.; Foglierini, M.; Jouffre, N.; Huynen, M.A.; Bork, P. STRING: Known and predicted protein-protein associations, integrated and transferred across organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, D433–D437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mering, C.; Huynen, M.; Jaeggi, D.; Schmidt, S.; Bork, P.; Snel, B. STRING: A database of predicted functional associations between proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snel, B.; Lehmann, G.; Bork, P.; Huynen, M.A. STRING: A web-server to retrieve and display the repeatedly occurring neighbourhood of a gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 3442–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D672–D677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y. Effectiveness of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Obes Surg. 2025, 35, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandvik, J.; Bjerkan, K.K.; Græslie, H.; Hoff, D.A.L.; Johnsen, G.; Klöckner, C.; Mårvik, R.; Nymo, S.; Hyldmo, Å.A.; Kulseng, B.E. Iron Deficiency and Anemia 10 Years After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass for Severe Obesity. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 679066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyfried, F.; Hoffmann, A.; Rullmann, M.; Schlegel, N.; Otto, C.; Hankir, M.K. Weight loss from caloric restriction vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery differentially regulates systemic and portal vein GDF15 levels in obese Zucker fatty rats. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 240, 113534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, J.W.; Pereira, M.J.; Kagios, C.; Kvernby, S.; Lundström, E.; Fanni, G.; Lundqvist, M.H.; Carlsson, B.C.L.; Sundbom, M.; Tarai, S.; et al. Short-term effects of obesity surgery versus low-energy diet on body composition and tissue-specific glucose uptake: A randomised clinical study using whole-body integrated 18F-FDG-PET/MRI. Diabetologia 2024, 67, 1399–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Örd, T.; Örd, D.; Örd, T. TRIB3 limits FGF21 induction during in vitro and in vivo nutrient deficiencies by inhibiting C/EBP-ATF response elements in the Fgf21 promoter. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2018, 1861, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T. Systemic iron homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1721–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.; Pauleau, A.-L.; Parganas, E.; Takahashi, Y.; Mages, J.; Ihle, J.N.; Rutschman, R.; Murray, P.J. SOCS3 regulates the plasticity of gp130 signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carow, B.; Rottenberg, M.E. SOCS3, a Major Regulator of Infection and Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardo, U.; Perrier, P.; Cormier, K.; Sotin, M.; Desquesnes, A.; Cannizzo, L.; Ruiz-Martinez, M.; Thevenin, J.; Billoré, B.; Jung, G.; et al. The hepatokine FGL1 regulates hepcidin and iron metabolism during the recovery from hemorrhage-induced anemia in mice. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynard, D.; Vaja, V.; Sun, C.C.; Corradini, E.; Chen, S.; López-Otín, C.; Grgurevic, L.; Hong, C.C.; Stirnberg, M.; Gütschow, M.; et al. Regulation of TMPRSS6 by BMP6 and iron in human cells and mice. Blood 2011, 118, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, Q.; Feng, D.; Wen, Y.; Xia, Y.; Colgan, S.P.; Eltzschig, H.K.; Ju, C. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2α Reprograms Liver Macrophages to Protect Against Acute Liver Injury Through the Production of Interleukin-6. Hepatology 2020, 71, 2105–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, M.; Srivastava, A.; Lee, J.; Hall, C.; Palaia, T.; Lau, R.; Brathwaite, C.; Ragolia, L. RYGB Is More Effective than VSG at Protecting Mice from Prolonged High-Fat Diet Exposure: An Occasion to Roll Up Our Sleeves? Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 3227–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsogiannos, P.; Kamble, P.G.; Pereira, M.J.; Sundbom, M.; Carlsson, P.-O.; Eriksson, J.W.; Espes, D. Changes in Circulating Cytokines and Adipokines After RYGB in Patients with and without Type 2 Diabetes. Obesity 2021, 29, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafida, S.; Mirshahi, T.; Nikolajczyk, B.S. The impact of bariatric surgery on inflammation: Quenching the fire of obesity? Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2016, 23, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockfield, S.; Chhabra, R.; Robertson, M.; Rehman, N.; Bisht, R.; Nanjundan, M. Links Between Iron and Lipids: Implications in Some Major Human Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramia, J.; Hao, Z.; Mumphrey, M.B.; Townsend, R.L.; Miard, S.; Carreau, A.-M.; Nadeau, M.; Frisch, F.; Baraboi, E.-D.; Grenier-Larouche, T.; et al. IGFBP-2 partly mediates the early metabolic improvements caused by bariatric surgery. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyoshi, M.; Katane, M.; Hamase, K.; Miyoshi, Y.; Nakane, M.; Hoshino, A.; Okawa, Y.; Mita, Y.; Kaimoto, S.; Uchihashi, M.; et al. D-Glutamate is metabolized in the heart mitochondria. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Qian, X.; Jiang, T.; Xiao, J.; Yin, M.; Xiong, M.; Wen, Z. Mechanism of dact2 gene inhibiting the occurrence and development of liver fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2022, 67, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Guo, Y.; Hamblin, M.; Chang, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.E. Inhibition of gluconeogenic genes by calcium-regulated heat-stable protein 1 via repression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 40584–40594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bononi, G.; Tuccinardi, T.; Rizzolio, F.; Granchi, C. α/β-Hydrolase Domain (ABHD) Inhibitors as New Potential Therapeutic Options against Lipid-Related Diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 9759–9785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. HDL and Scavenger Receptor Class B Type I (SRBI). Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022, 1377, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, K.; Quiñones, V.; Amigo, L.; Santander, N.; Salas-Pérez, F.; Xavier, A.; Fernández-Galilea, M.; Carrasco, G.; Cabrera, D.; Arrese, M.; et al. Lipoprotein receptor SR-B1 deficiency enhances adipose tissue inflammation and reduces susceptibility to hepatic steatosis during diet-induced obesity in mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 158909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, M.F.; Tao, H.; Linton, E.F.; Yancey, P.G. SR-BI: A Multifunctional Receptor in Cholesterol Homeostasis and Atherosclerosis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Xiong, J.; Cai, M.; Wang, C.; He, Q.; Wang, B.; Chen, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, B.; Han, S.; et al. SCARB1 links cholesterol metabolism-mediated ferroptosis inhibition to radioresistance in tumor cells. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 77, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilli, C.; Hoeh, A.E.; De Rossi, G.; Moss, S.E.; Greenwood, J. LRG1: An emerging player in disease pathogenesis. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stevenson, M.; Tirumalasetty, M.B.; Srivastava, A.; Miao, Q.; Brathwaite, C.; Ragolia, L. Analysis of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and High-Fat Feeding Reveals Hepatic Transcriptome Reprogramming: Ironing out the Details. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020479

Stevenson M, Tirumalasetty MB, Srivastava A, Miao Q, Brathwaite C, Ragolia L. Analysis of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and High-Fat Feeding Reveals Hepatic Transcriptome Reprogramming: Ironing out the Details. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):479. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020479

Chicago/Turabian StyleStevenson, Matthew, Munichandra Babu Tirumalasetty, Ankita Srivastava, Qing Miao, Collin Brathwaite, and Louis Ragolia. 2026. "Analysis of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and High-Fat Feeding Reveals Hepatic Transcriptome Reprogramming: Ironing out the Details" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020479

APA StyleStevenson, M., Tirumalasetty, M. B., Srivastava, A., Miao, Q., Brathwaite, C., & Ragolia, L. (2026). Analysis of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and High-Fat Feeding Reveals Hepatic Transcriptome Reprogramming: Ironing out the Details. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020479