Proton Beam Therapy for Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: A Six-Case Series with Dosimetric Comparison and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection and Treatment

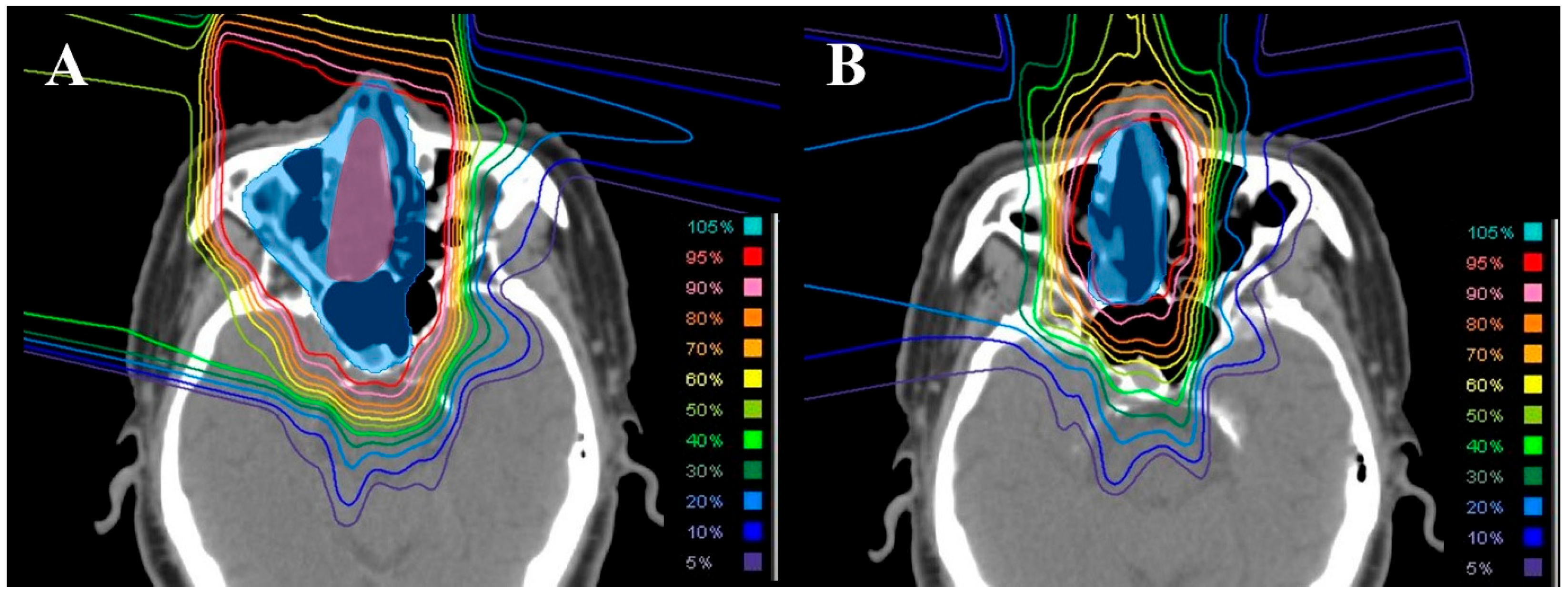

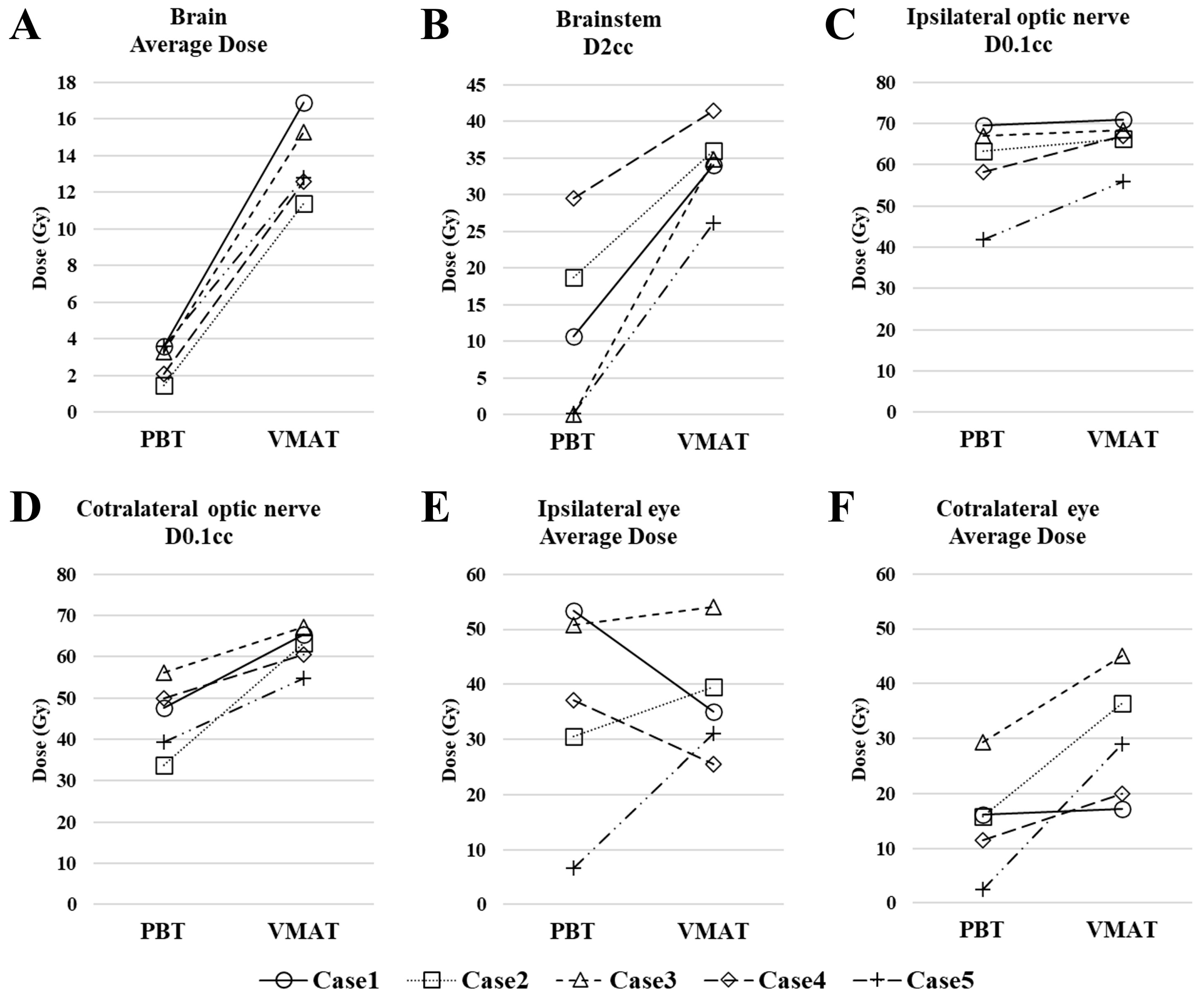

2.2. Dosimetric Comparison with Photon Therapy

3. Results

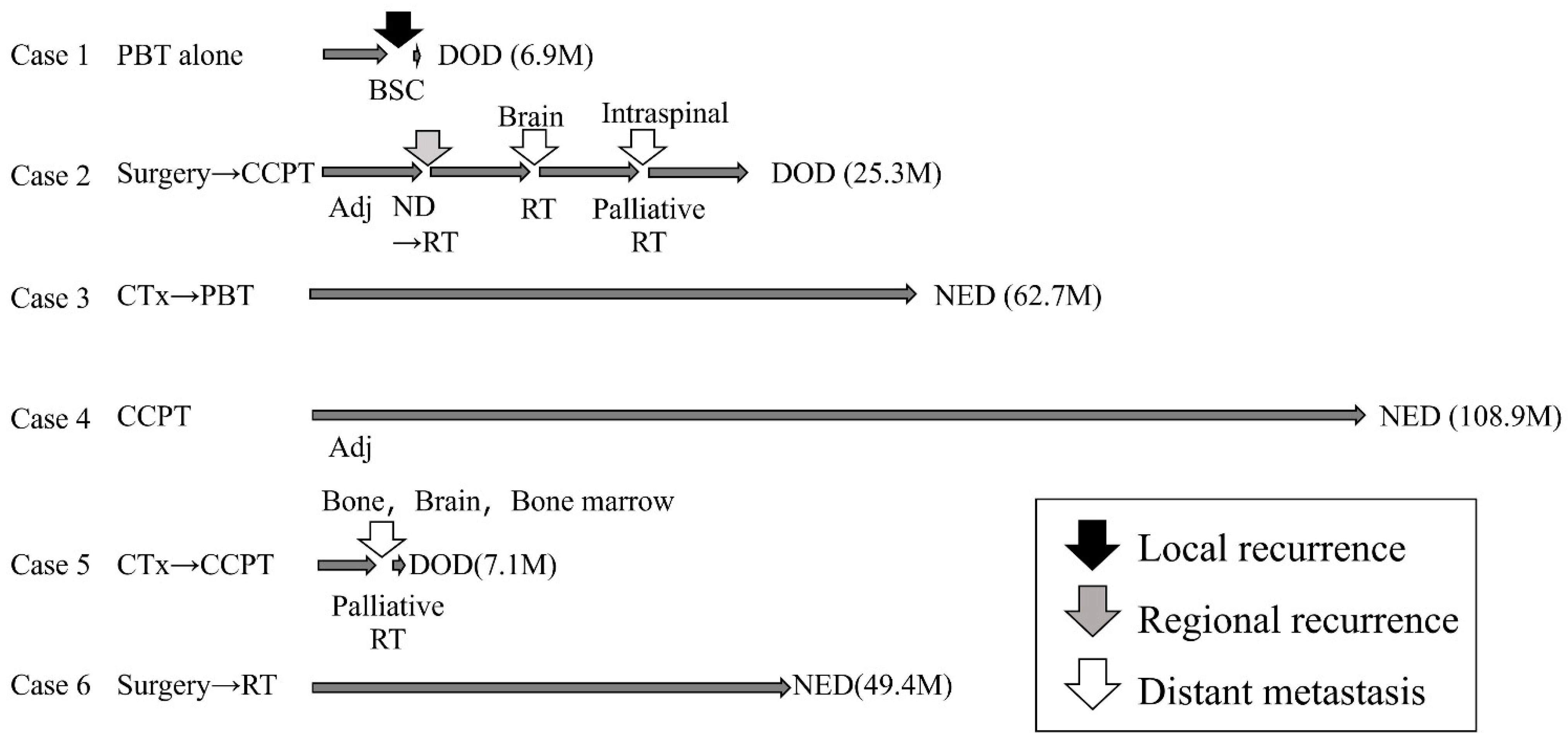

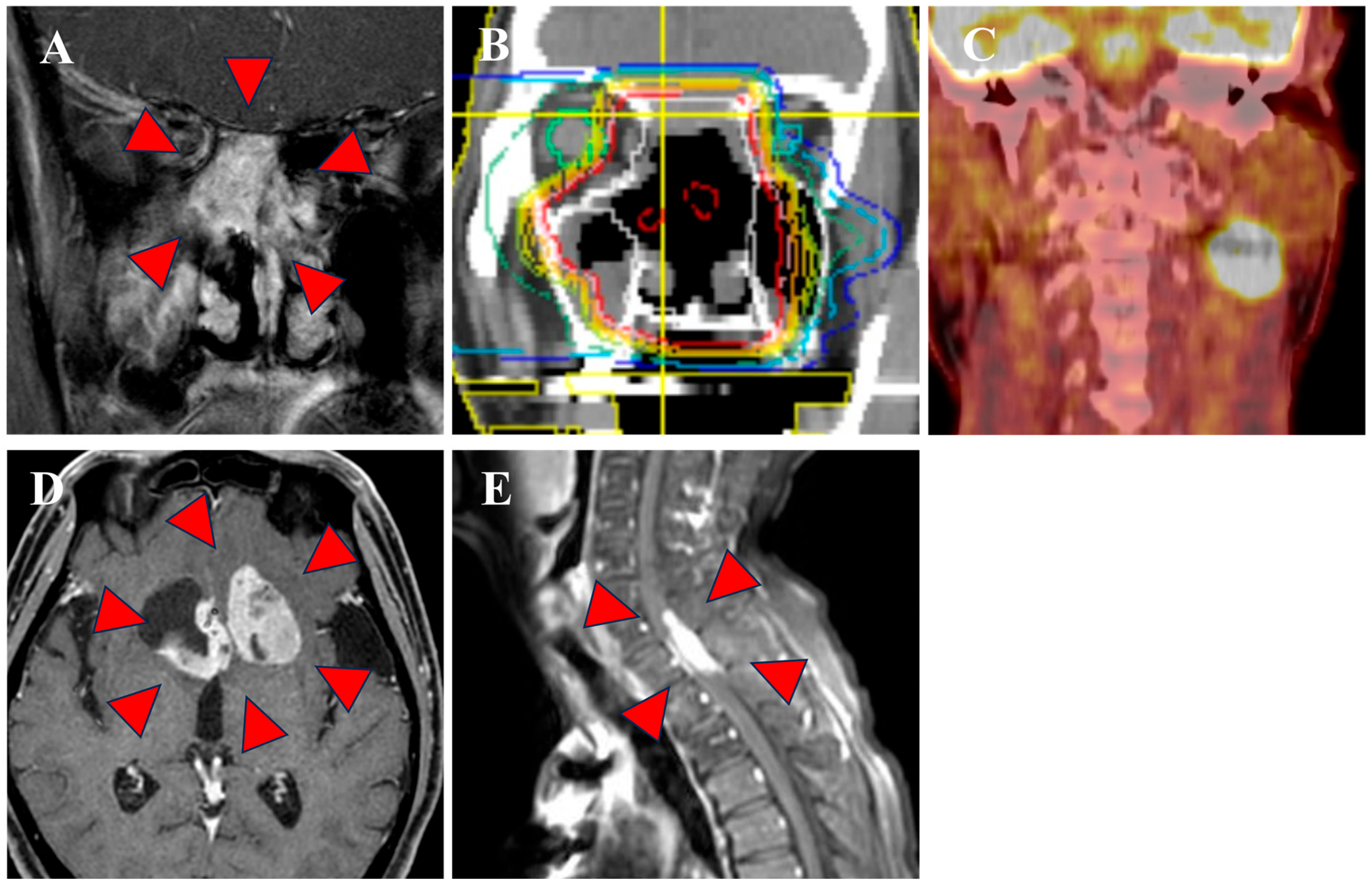

3.1. Clinical Outcomes

3.2. Dosimetric Comparison

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SNEC | sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma |

| PBT | proton beam therapy |

| RBE | relative biological effectiveness |

| IC | induction chemotherapy |

| EMA | epithelial membrane antigen |

| CD | cluster of differentiation antigen |

| GTV | gross tumor volume |

| CTV | clinical target volume |

| UICC | Union for International Cancer Control |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| VMAT | volumetric-modulated arc therapy |

| PTV | planning target volume |

| OAR | organs at risk |

| D2cc | most-exposed 2 cm3 |

| D0.1cc | most-exposed 0.1 cm3 |

References

- Patel, T.D.; Vazquez, A.; Dubal, P.M.; Baredes, S.; Liu, J.K.; Eloy, J.A. Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: A Population-Based Analysis of Incidence and Survival: Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015, 5, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keilin, C.A.; VanKoevering, K.K.; McHugh, J.B.; McKean, E.L. Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: 15 Years of Experience at a Single Institution. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 2022, 84, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, I.; Kishibe, K.; Takahara, M.; Katada, H.; Hayashi, T.; Harabuchi, Y. Sevens Cases of Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Nasal and Paranasal Sinuses. Jpn. J. Rhinol. 2021, 60, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turri-Zanoni, M.; Maragliano, R.; Battaglia, P.; Giovannardi, M.; Antognoni, P.; Lombardi, D.; Morassi, M.L.; Pasquini, E.; Tarchini, P.; Asioli, S.; et al. The Clinicopathological Spectrum of Olfactory Neuroblastoma and Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Refinements in Diagnostic Criteria and Impact of Multimodal Treatments on Survival. Oral Oncol. 2017, 74, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Laan, T.P.; Bij, H.P.; van Hemel, B.M.; Plaat, B.E.C.; Wedman, J.; van der Laan, B.F.A.M.; Halmos, G.B. The Importance of Multimodality Therapy in the Treatment of Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 270, 2565–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, E.H.; Diaz, A.; Yilmaz, T.; Roberts, D.; Levine, N.; De Monte, F.; Hanna, E.Y.; Kupferman, M.E. Multimodality Treatment for Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. Head Neck 2012, 34, 1372–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likhacheva, A.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Hanna, E.; Kupferman, M.; Demonte, F.; El-Naggar, A.K. Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: Impact of Differentiation Status on Response and Outcome. Head Neck Oncol. 2011, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.-P.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Chang, Y.-L.; Lou, P.-J.; Yang, T.-L.; Ting, L.-L.; Ko, J.-Y. Postirradiated Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Sinonasal Tract. Laryngoscope 2008, 118, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babin, E.; Rouleau, V.; Vedrine, P.O.; Toussaint, B.; de Raucourt, D.; Malard, O.; Cosmidis, A.; Makaeieff, M.; Dehesdin, D. Small Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2006, 120, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Network(NCCN), NCC. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Head and Neck Cancers. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Smith, S.R.; Som, P.; Fahmy, A.; Lawson, W.; Sacks, S.; Brandwein, M. A Clinicopathological Study of Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma and Sinonasal Undifferentiated Carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2000, 110, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.H.; Wang, Z.; Wong, W.W.; Murad, M.H.; Buckey, C.R.; Mohammed, K.; Alahdab, F.; Altayar, O.; Nabhan, M.; Schild, S.E.; et al. Charged Particle Therapy versus Photon Therapy for Paranasal Sinus and Nasal Cavity Malignant Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paré, A.; Blanchard, P.; Rosellini, S.; Aupérin, A.; Gorphe, P.; Casiraghi, O.; Temam, S.; Bidault, F.; Page, P.; Kolb, F.; et al. Outcomes of Multimodal Management for Sinonasal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amit, M.; Abdelmeguid, A.S.; Watcherporn, T.; Takahashi, H.; Tam, S.; Bell, D.; Ferrarotto, R.; Glisson, B.; Kupferman, M.E.; Roberts, D.B.; et al. Induction Chemotherapy Response as a Guide for Treatment Optimization in Sinonasal Undifferentiated Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Ohnishi, K.; Aihara, T.; Mizumoto, M.; Fukumitsu, N.; Sugawara, K.; Okumura, T.; Sakurai, H. Proton Beam Therapy for Locally Advanced and Unresectable (T4bN0M0) Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Ethmoid Sinus: A Report of Seven Cases and a Literature Review. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 10, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Nakayama, M.; Ohnishi, K.; Tanaka, S.; Nakamura, M.; Murakami, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Baba, K.; Fujii, K.; Mizumoto, M.; et al. Proton Beam Therapy in Multimodal Treatment for Locally Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinus. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 18, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argota-Perez, R.; Sharma, M.B.; Elstrøm, U.V.; Møller, D.S.; Grau, C.; Jensen, K.; Holm, A.I.S.; Korreman, S.S. Dose and Robustness Comparison of Nominal, Daily and Accumulated Doses for Photon and Proton Treatment of Sinonasal Cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2022, 173, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, E.G.; Butler, J.J.; Mackay, B.; Goepfert, H. Neuroblastomas and Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Nasal Cavity: A Proposed New Classification. Cancer 1982, 50, 2388–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case | Age | Sex | Stage | Reg Ion | Size | Pathological Markers | Treatment | Dose | Recurrence | Out Come | Adverse Event | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | N | (cm) | Mitosis (/10 HPF) | Apoptosis (/10 HPF) | AE1/AE3 | EMA | S-100 | SYP | CGA | CD56 | Ki67 (%) | (Regimen) | (Gy (RBE)) | |||||||

| 1 | 84 | M | 4b | 0 | Nasal cavity | 6.7 | 25 | ≥50 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | NA | 1 | 90 | PBT alone | 70 | Local | DOD | - |

| 2 | 72 | M | 2 | 0 | Nasal cavity | 2.5 | 40 | ≥50 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | NA | Surgery +CCPT (EP) +Adj (EP) | 66 | Cervical LN Distant | DOD | - |

| 3 | 62 | F | 4b | 0 | Ethmoid sinus | 4.5 | 20 | ≥50 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 70 | Induction (TPF) + PBT | 66 | - | NED | - |

| 4 | 76 | M | 1 | 0 | Nasal cavity | 4.1 | 25 | ≥50 | NA | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 100 | CCPT (EP) +Adj (EP) | 66 | - | NED | - |

| 5 | 31 | F | 4b | 2b | Nasal cavity | 5.6 | 20 | ≥50 | 1 | NA | NA | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | Induction (EP) + CCPT (AMR) | 60 | Distant | DOD | - |

| 6 | 81 | M | 3 | 0 | Nasal cavity | 7.2 | 8 | ≥50 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | NA | Surgery + RT (Photon + Proton) | Photon: 40 PBT: 20 | - | NED | Vision decreased Grade 4 |

| Author | Year | Number of Patients | Radiotherapy Modality | Median Observation Period (Months) | Treatment * | Overall Survival | Local Recurrence | Neck Recurrence | Distant Metastasis | Metastasis Region | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Chemotherapy | Radiotherapy | Radiation Dose (Gy) | ||||||||||

| Keilin et al. [2] | 2022 | 13 | Photon | - | 5 | 8 | 11 | 43.5–70 | 74.6% (5y) | 7.7% | 7.7% | 7.7% | Lung |

| 6.3–138.2 | |||||||||||||

| Sekine et al. [3] | 2021 | 7 | Photon | - | 2 | 7 | 6 | 40–60 | 28.6% (5y) | 14.3% | 14.3% | 42.9% | Brain, Liver, Bone |

| 2–192 | |||||||||||||

| Turri-Zanoni et al. [4] | 2017 | 22 | Photon | 22 | 22 | >10 | 20 | 50–66 | 42.6% (5y) | 13.6% | 18.2% | 63.6% | Brain, Liver, Bone, Lung, Kidney, Pancreas |

| van der Laan et al. [5] | 2013 | 12 | Photon | 30.5 | 8 | 0 | 9 | 30–70.2 | 41.7% | 16.7% | 16.7% | 8.3% | - |

| Mitchell et al. [6] | 2012 | 28 | Photon | 48.6 | 13 | 16 | 16 | - | 66.9% (5y) | 21.4% | 25% | 14.3% | - |

| Likhacheva et al. [7] | 2011 | 20 | Photon | 60 | 15 | 13 | 17 | >60 | - | 10% | 15% | 10% | Dura mater, Pia mater |

| Wang et al. [8] | 2008 | 10 | Photon | 74.5 | 10 | 4 | 5 | - | 70% (5y) | 20% (5y) | 0% | 40% (5y) | Brain, Liver, Bone, Lung |

| Babin et al. [9] | 2006 | 21 | Photon | 12 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 30–78 | - | 19% | 14.3% | 19% | Brain, Liver, Bone |

| Current study | 2025 | 6 | Proton | 37.4 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 60–70 (RBE) | 50% (4y) | 17% | 17% | 33% | Brain, Bone, Intraspinal, Bone marrow |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nitta, H.; Saito, T.; Matsuoka, R.; Matsumoto, S.; Tanaka, S.; Nakayama, M.; Osawa, K.; Murakami, M.; Baba, K.; Nakamura, M.; et al. Proton Beam Therapy for Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: A Six-Case Series with Dosimetric Comparison and Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020477

Nitta H, Saito T, Matsuoka R, Matsumoto S, Tanaka S, Nakayama M, Osawa K, Murakami M, Baba K, Nakamura M, et al. Proton Beam Therapy for Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: A Six-Case Series with Dosimetric Comparison and Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020477

Chicago/Turabian StyleNitta, Hazuki, Takashi Saito, Ryota Matsuoka, Shin Matsumoto, Shuho Tanaka, Masahiro Nakayama, Kotaro Osawa, Motohiro Murakami, Keiichiro Baba, Masatoshi Nakamura, and et al. 2026. "Proton Beam Therapy for Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: A Six-Case Series with Dosimetric Comparison and Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020477

APA StyleNitta, H., Saito, T., Matsuoka, R., Matsumoto, S., Tanaka, S., Nakayama, M., Osawa, K., Murakami, M., Baba, K., Nakamura, M., Fujii, K., Oshiro, Y., Mizumoto, M., Tabuchi, K., Matsubara, D., & Sakurai, H. (2026). Proton Beam Therapy for Sinonasal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: A Six-Case Series with Dosimetric Comparison and Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020477