A Retrospective Analysis of Hepatic Disease Burden and Progression in a Hospital-Based Romanian Cohort Using Integrated Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data (2019–2023)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting and Patient Population

2.2. Data Source and Extraction

2.3. Data Preprocessing and Cohort Construction

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Descriptive Statistics and Distributional Analyses

2.6. Hospitalization Burden and Temporal Dynamics

2.7. Analysis of Comorbidities and Complications

2.8. Analysis of Liver Disease Severity

2.9. Correlation and Longitudinal Analyses

2.10. Cluster Analysis

3. Results

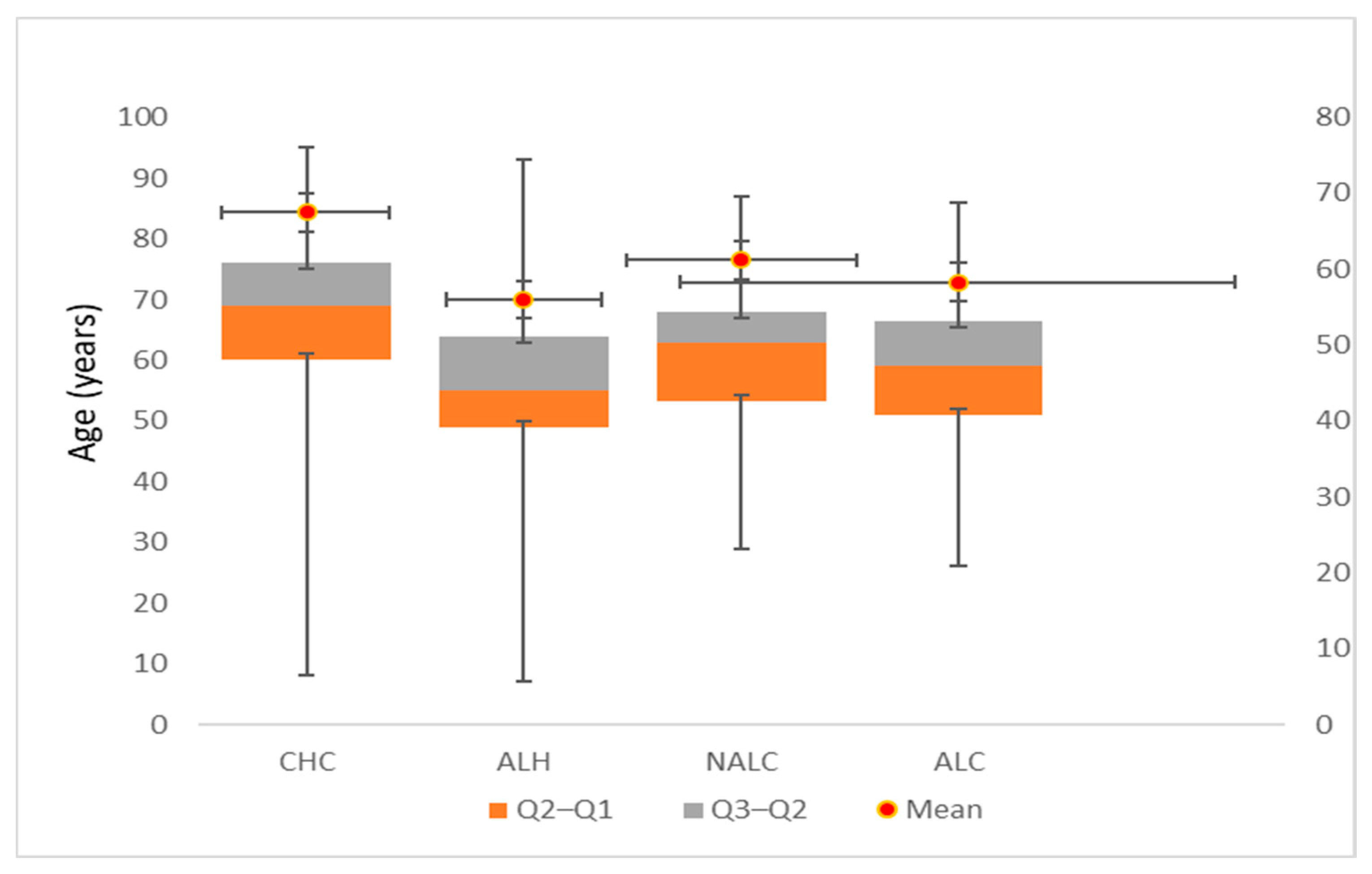

3.1. Cohort Characteristics and Age Distribution by Liver Disease Etiology

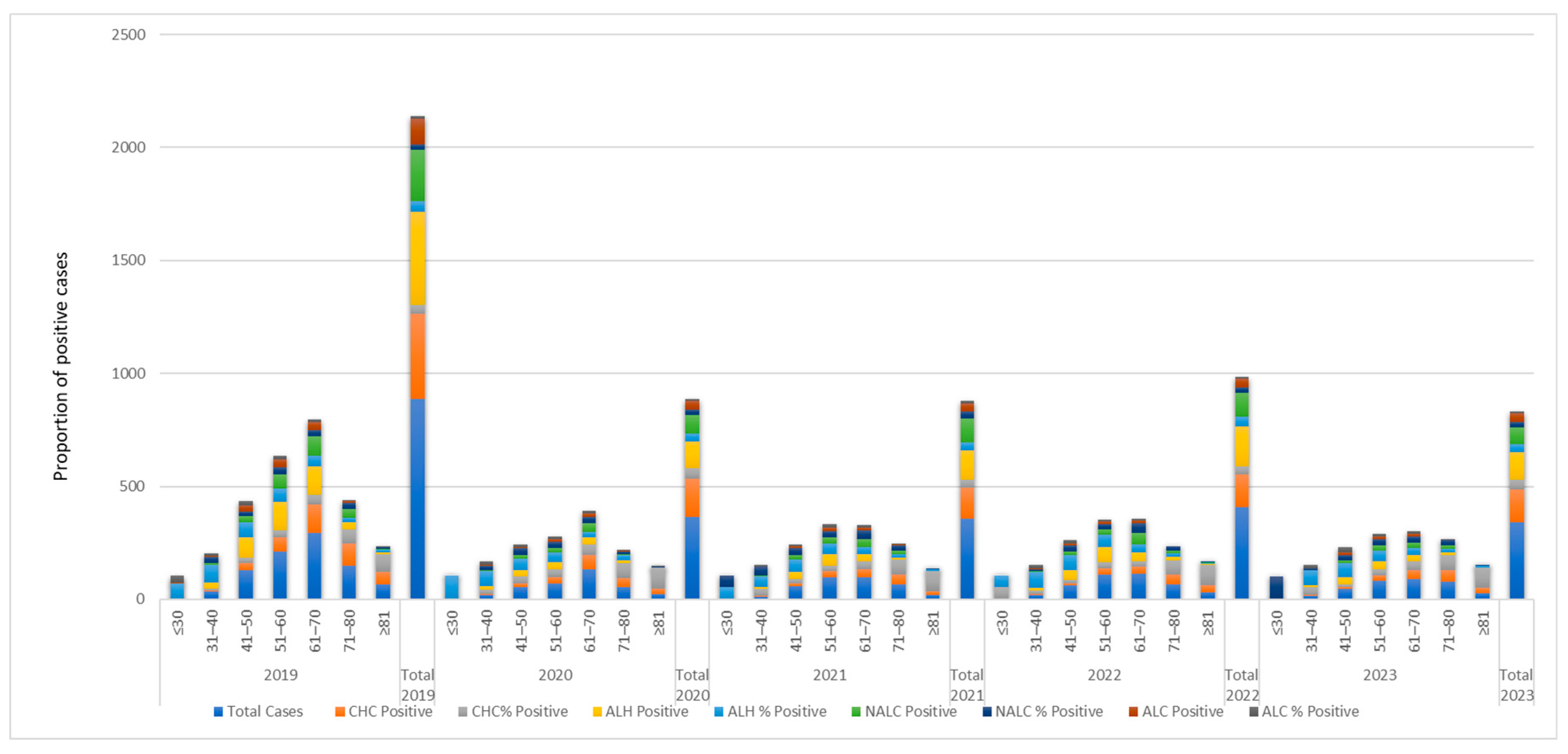

3.2. Age-Related Epidemiological Patterns of Liver Disease Etiologies

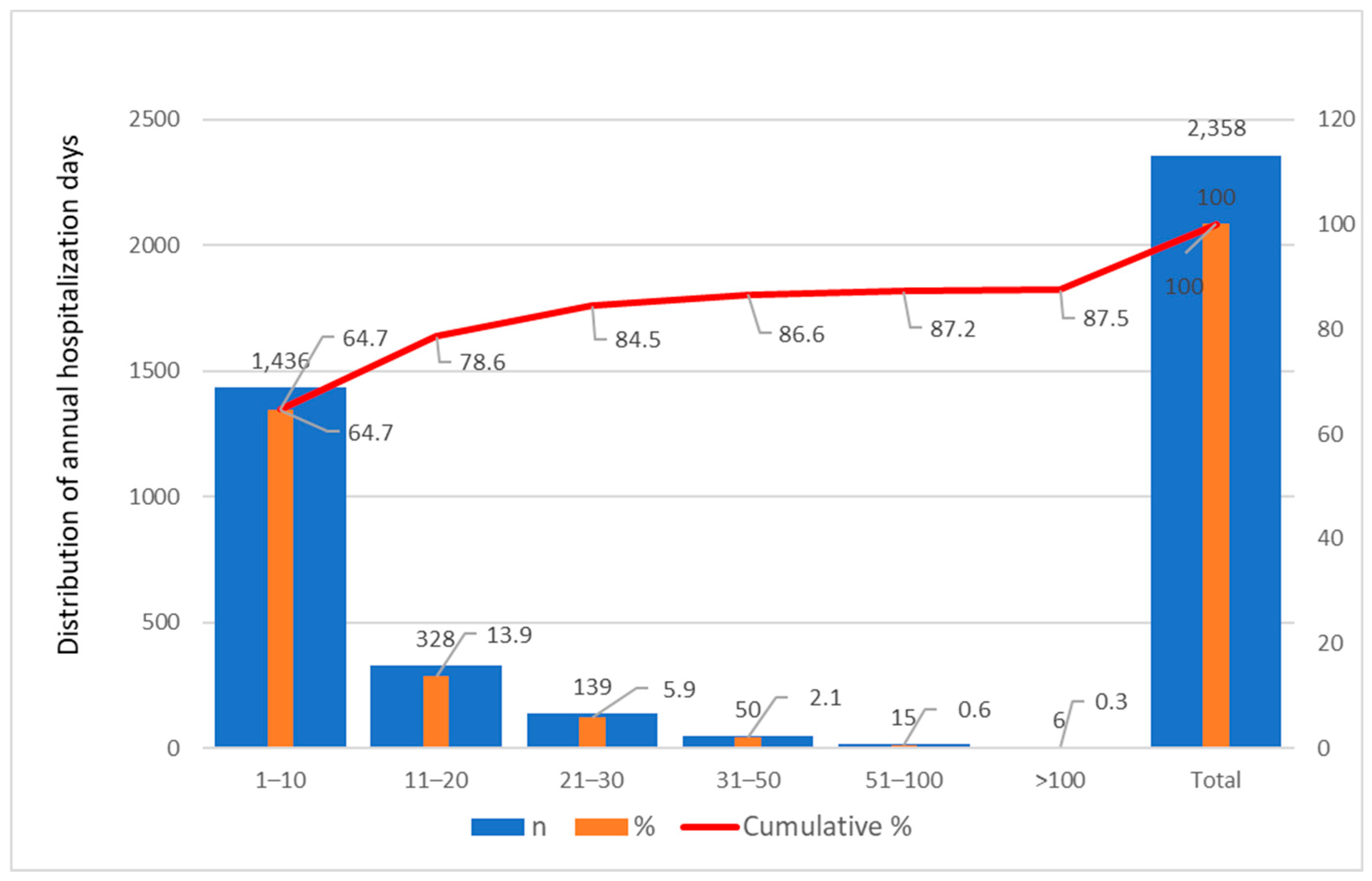

3.3. Temporal Trends in Hospitalization Duration (2019–2023)

3.4. Hospitalization Burden Stratified by Diagnosis and Temporal Trends

3.4.1. Diagnosis-Specific Hospitalization Duration

3.4.2. Temporal Trends and Stabilization of Hospital Stays

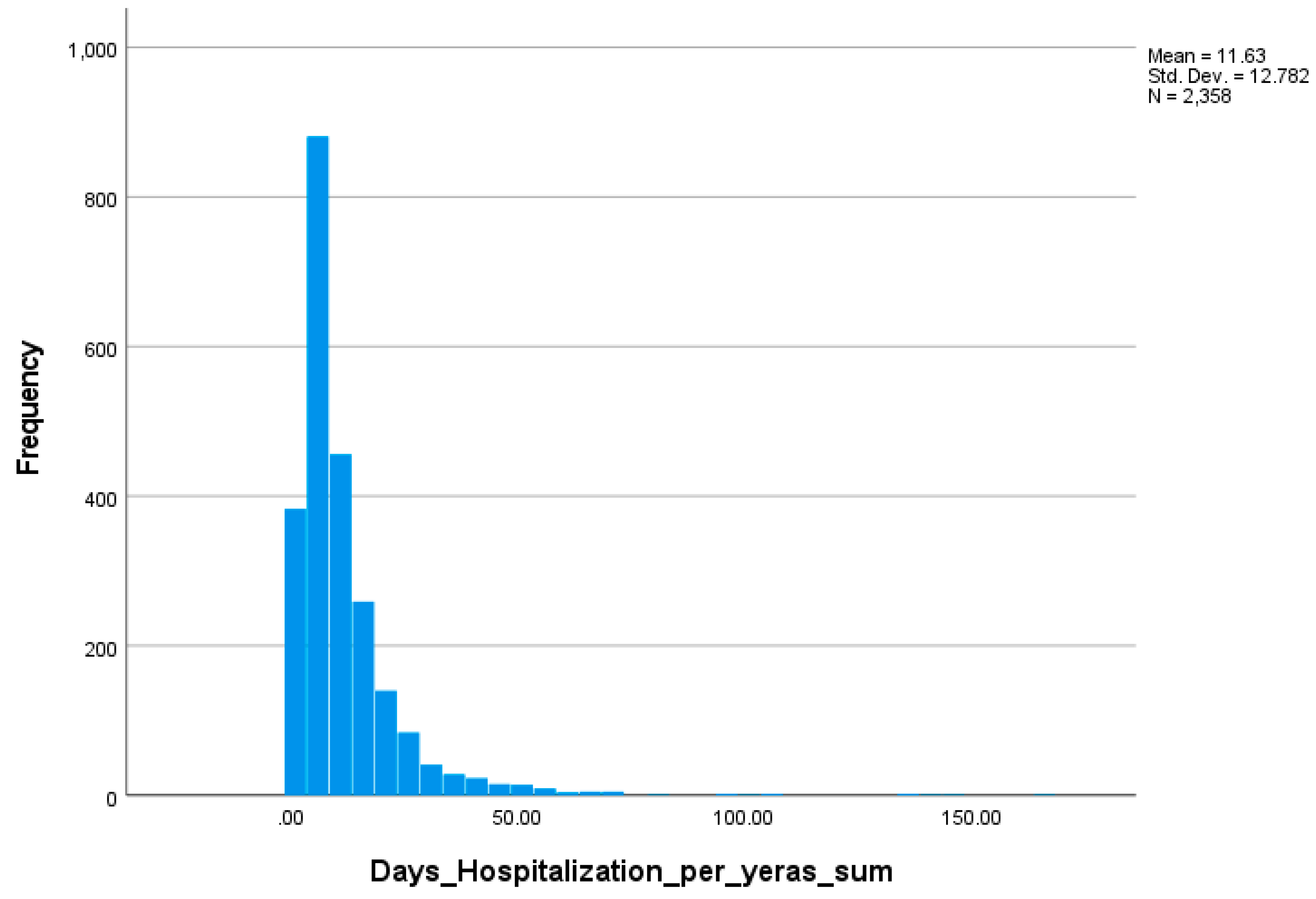

3.4.3. Statistical Modeling and Distributional Analysis

3.5. Predictors of Hospitalization Duration: Generalized Linear Model Analysis

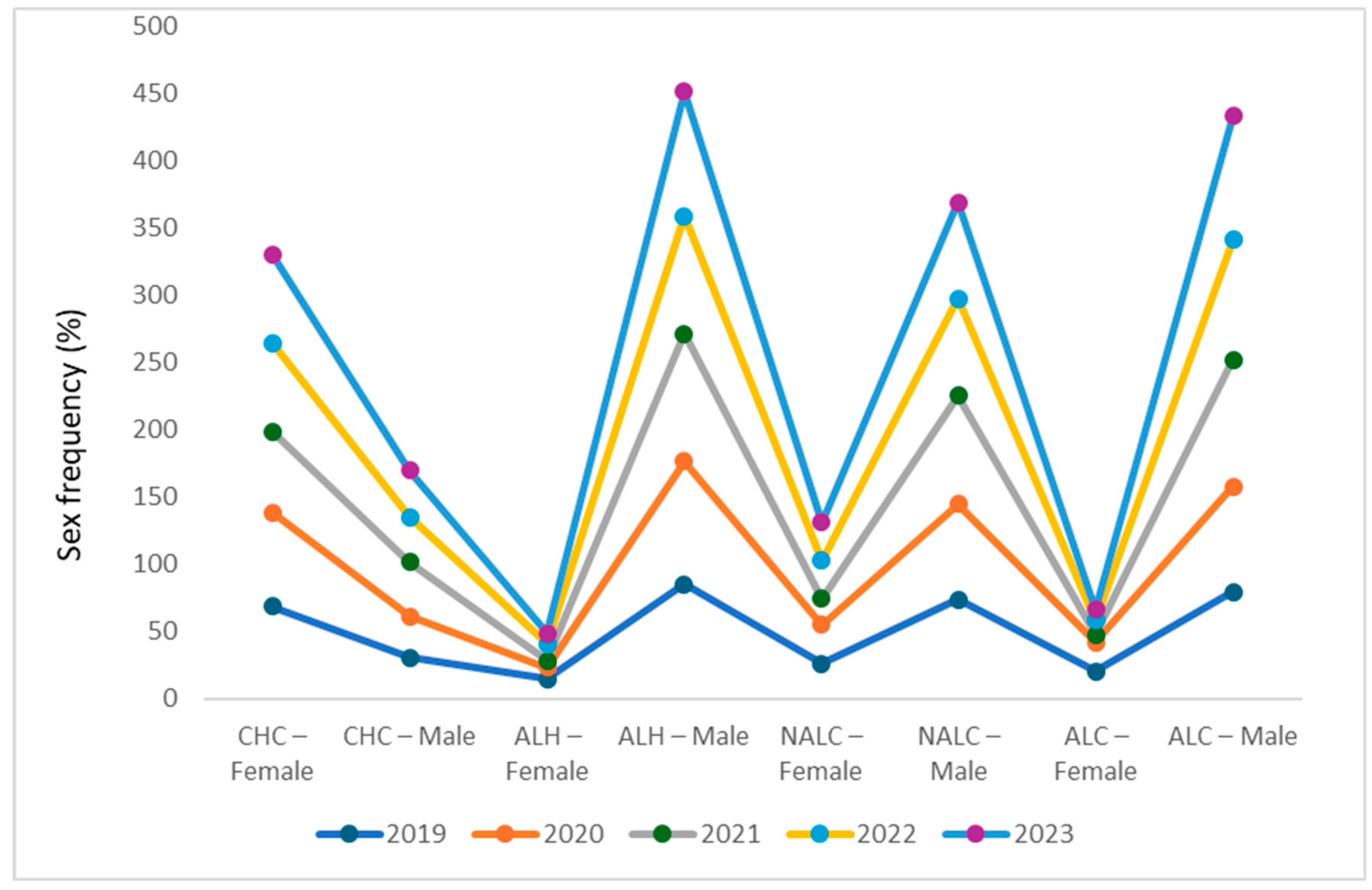

3.6. Distinct and Persistent Sex-Based Etiological Patterns

3.7. Child–Pugh Classification and Predictors

3.7.1. Univariate Associations Between Etiology and Disease Severity

3.7.2. Multivariate Predictors of Child–Pugh Class

3.7.3. Demographic and Temporal Distributions of Disease Severity

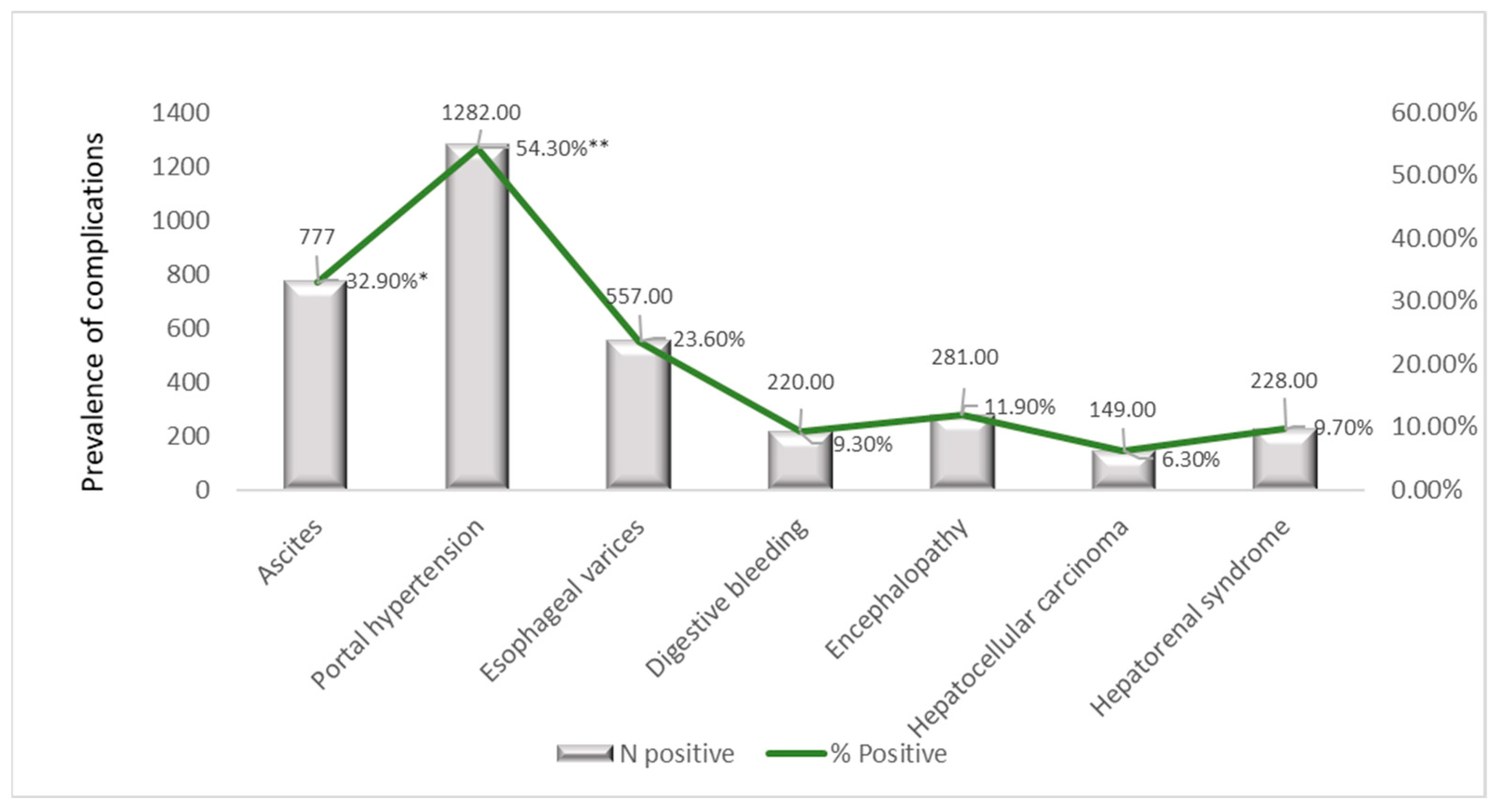

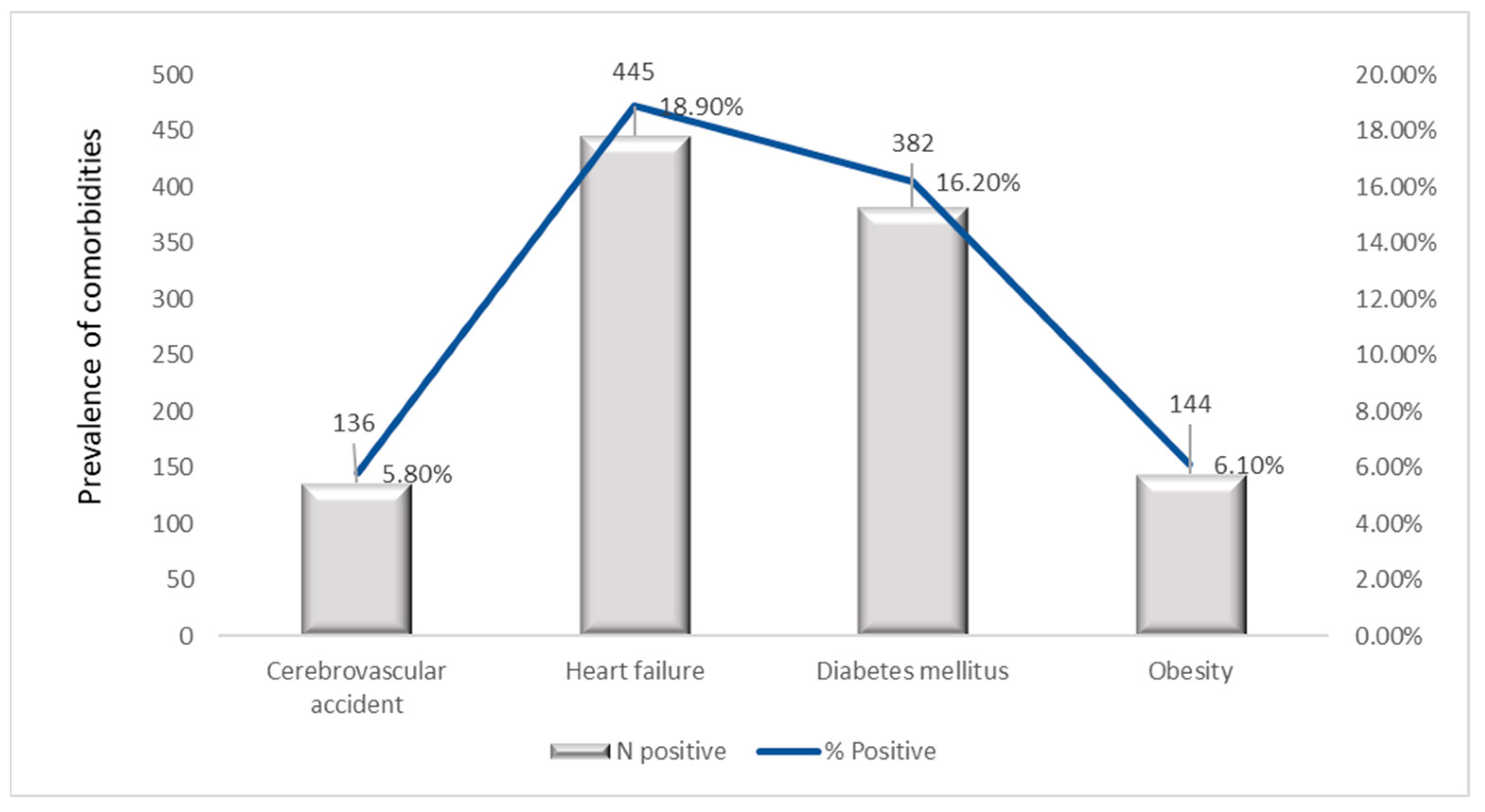

3.8. Prevalence of Comorbidities and Complications

3.8.1. Stratification of Comorbidities per Years

3.8.2. Age-Stratified Comorbidities Prevalence

3.8.3. Sex-Based Distribution of Comorbidities

3.8.4. Temporal Trends in Liver-Related Complications (2019–2023)

3.8.5. Prevalence of Liver-Related Complications by Age Group

3.8.6. Sex-Stratified Prevalence of Major Hepatic Complications

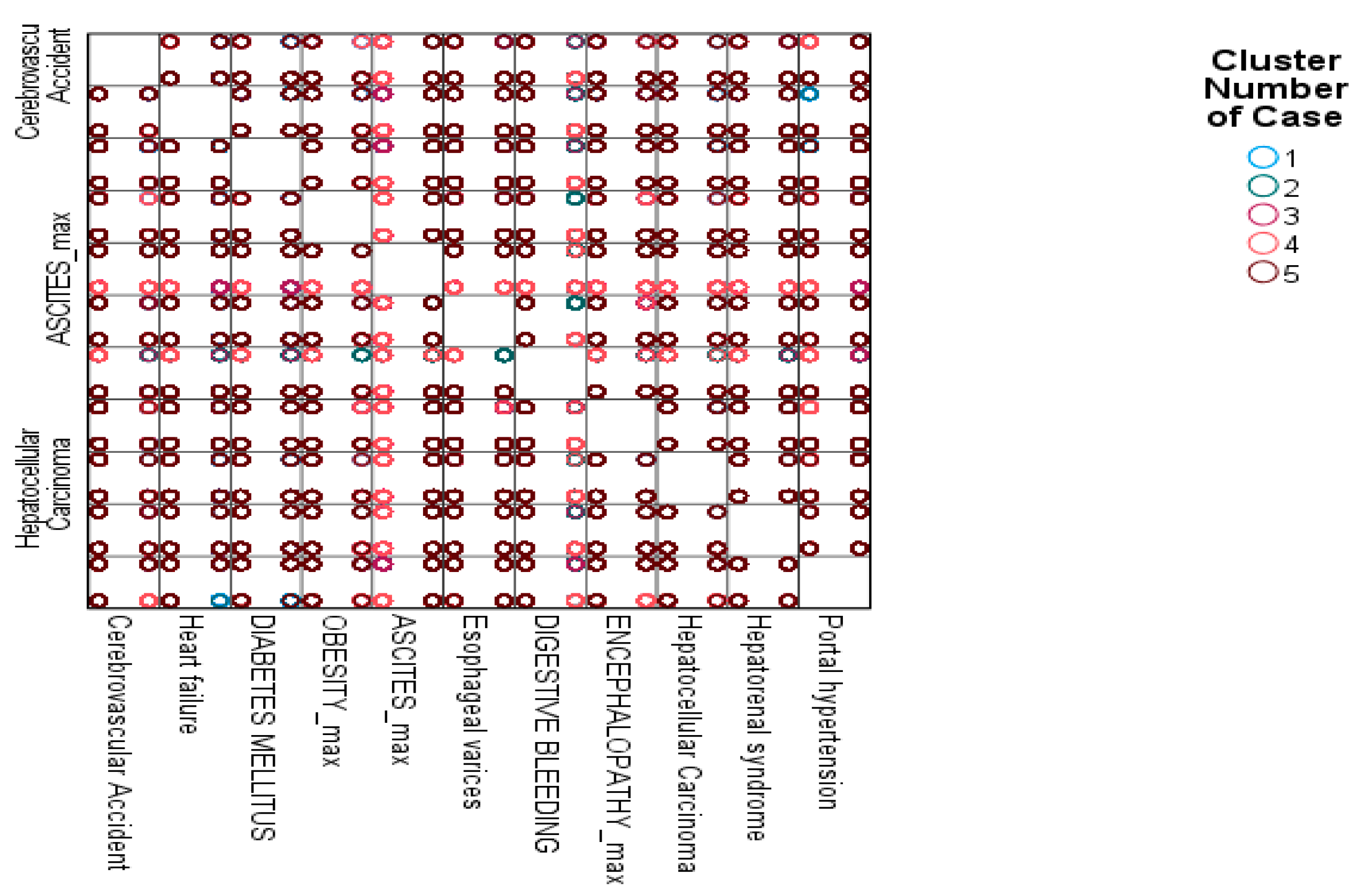

3.8.7. K-Means Clustering of Patient Profiles Based on Complications

3.9. Hospitalization Patterns in the Multiple ID Cohort

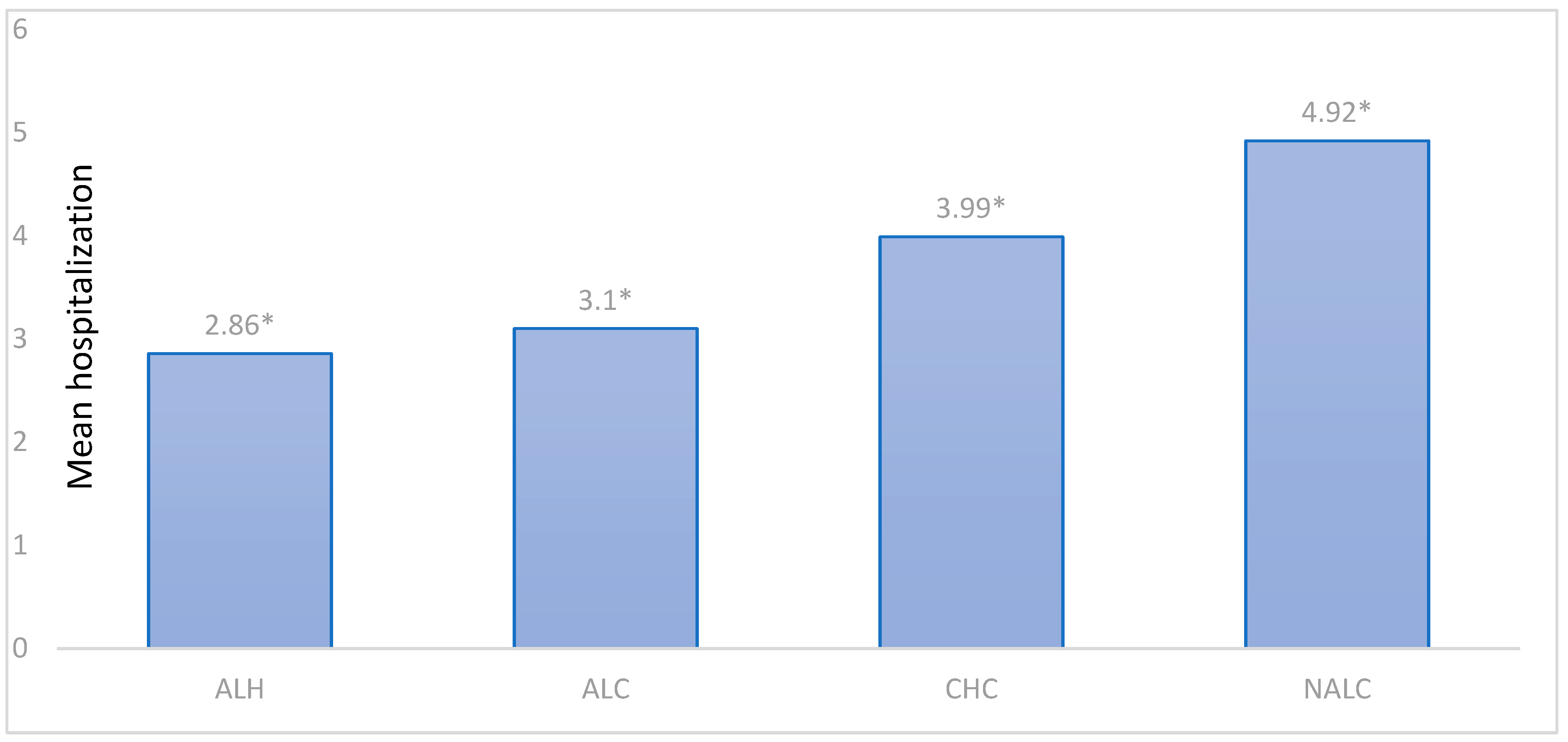

3.9.1. Hospitalization Frequency Stratification by Diagnostic

3.9.2. Patient-Level Hospitalization Stratification by Age Group

3.9.3. Descriptive Statistics of Hospitalization Frequency by Sex and Diagnostic Group

3.9.4. Hospitalizations Across Liver Disease Subtypes

3.9.5. Correlation Analysis

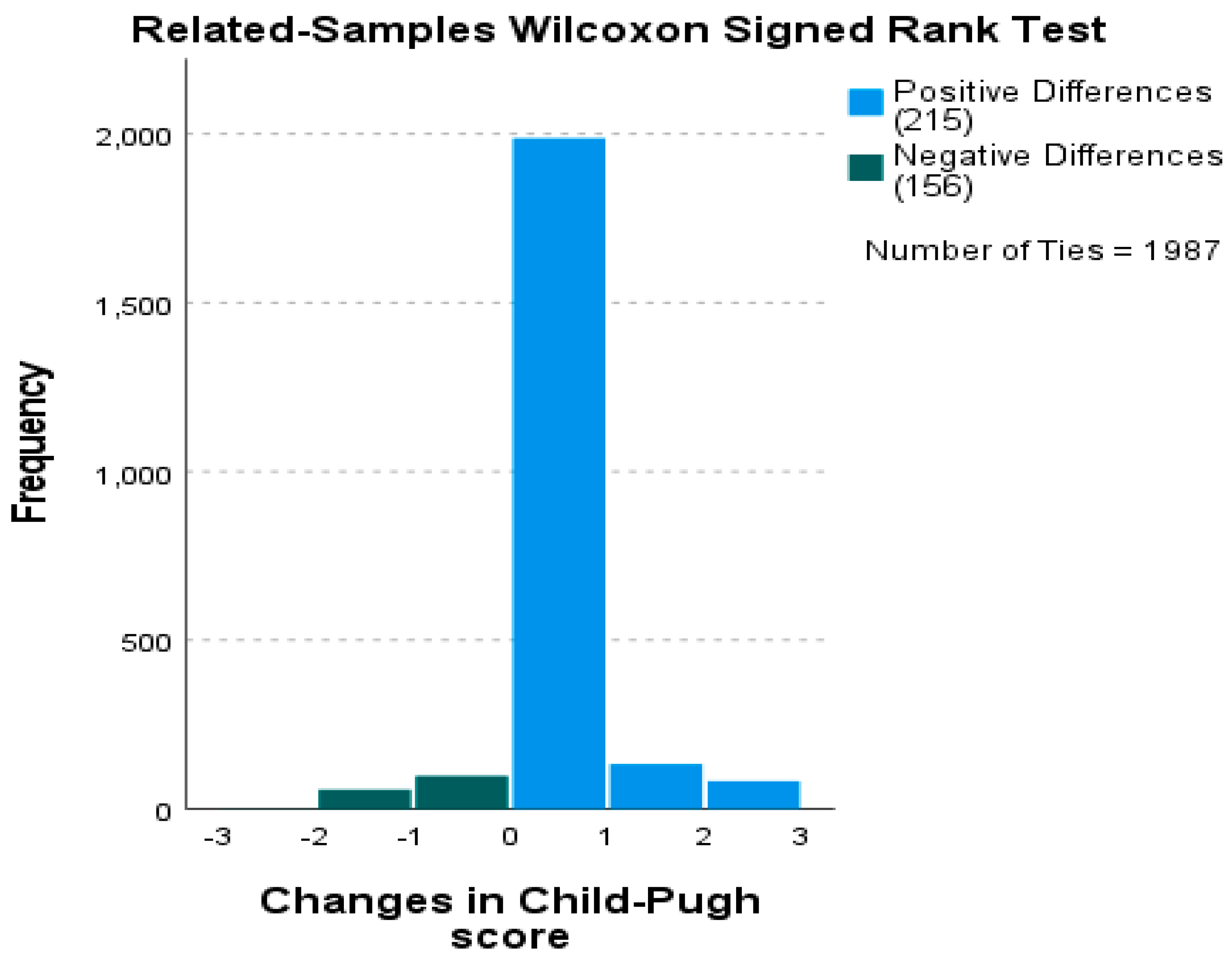

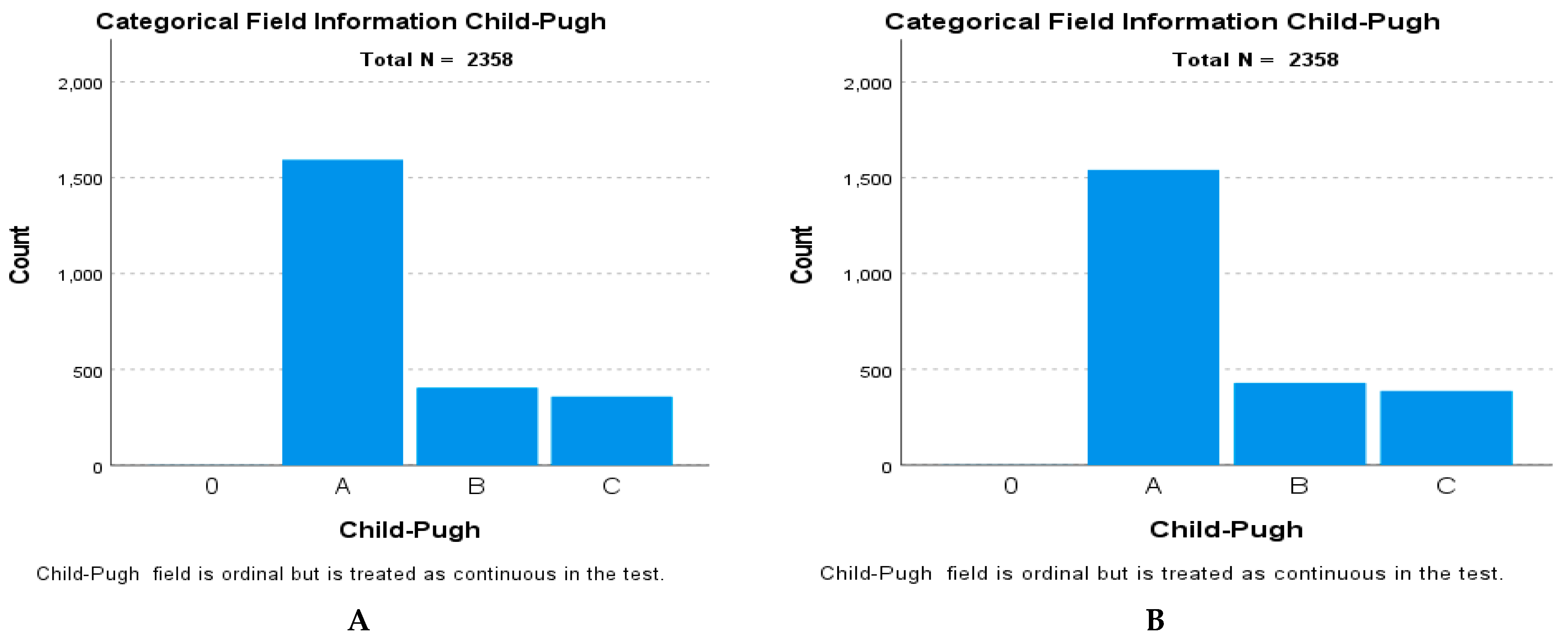

3.10. Longitudinal Child–Pugh Score Analysis

3.11. Pandemic vs. Non-Pandemic Periods and Hospitalization Burden

4. Discussion

4.1. Analytical Framework: Integrating Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Perspectives

4.2. Demographics and Hospitalization Patterns

4.3. Child–Pugh Classification

4.4. Comorbidities and Complications

4.5. Cluster-Defined Phenotypes and Their Clinical Significance

4.6. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHC | chronic hepatitis C |

| ALH | hepatitis associated with alcohol |

| ALC | cirrhosis associated with alcohol |

| NALC | non-alcoholic cirrhosis |

| CLD | chronic liver diseases |

| MASLD | metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| AH | arterial hypertension |

| CVA | cerebrovascular accident |

| HF | heart failure |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| Ob | obesity |

| EV | esophageal varices |

| DB | digestive bleeding |

| HE | hepatic encephalopathy |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HRS | hepatorenal syndrome |

| PH | portal hypertension |

| CIs | confidence intervals |

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model |

| EMMs | Estimated Marginal Means |

| ORs | odds ratios |

| N | number of patients in full cohort |

| n | number of patients in subcohort |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| Df | degrees of freedom |

References

- Moon, A.M.; Singal, A.G.; Tapper, E.B. Contemporary Epidemiology of Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2650–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posuwan, N.; Wasitthankasem, R.; Pimsing, N.; Phaengkha, W.; Ngamnimit, S.; Vichaiwattana, P.; Klinfueng, S.; Raksayod, M.; Poovorawan, Y. Hepatitis B Prevalence in an Endemic Area of Hepatitis C Virus: A Population-Based Study Implicated in Hepatitis Elimination in Thailand. J. Virus Erad. 2024, 10, 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global Burden of Liver Disease: 2023 Update. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Yuan, Y.; Shen, H.; Gao, J.; Kong, X.; Che, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Dong, E.; Xiao, J. Liver Diseases: Epidemiology, Causes, Trends and Predictions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asrani, S.K.; Devarbhavi, H.; Eaton, J.; Kamath, P.S. Burden of Liver Diseases in the World. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report 2024: Action for Access in Low- and Middle-Income Countries, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-92-4-009167-2. [Google Scholar]

- Duo, H.; You, J.; Du, S.; Yu, M.; Wu, S.; Yue, P.; Cui, X.; Huang, Y.; Luo, J.; Pan, H.; et al. Liver Cirrhosis in 2021: Global Burden of Disease Study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0328493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease—A Global Public Health Perspective. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Wong, G.; Anstee, Q.M.; Henry, L. The Global Burden of Liver Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 1978–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimpin, L.; Cortez-Pinto, H.; Negro, F.; Corbould, E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Webber, L.; Sheron, N. Burden of Liver Disease in Europe: Epidemiology and Analysis of Risk Factors to Identify Prevention Policies. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.L.; Ng, C.H.; Huang, D.Q.; Chan, K.E.; Tan, D.J.; Lim, W.H.; Yang, J.D.; Tan, E.; Muthiah, M.D. Global Incidence and Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, S32–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 13–27. [CrossRef]

- Stefan, N.; Cusi, K. A Global View of the Interplay between Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabb, D.W.; Im, G.Y.; Szabo, G.; Mellinger, J.L.; Lucey, M.R. Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcohol-Associated Liver Diseases: 2019 Practice Guidance From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2020, 71, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, R.; Ren, S.; He, T.; Mi, H.; Jiang, W.; Su, C. Global Burden of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease from 1990 to 2021 and the Prediction for the next 10 Years. Prev. Med. Rep. 2025, 59, 103248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golabi, P.; Owrangi, S.; Younossi, Z.M. Global Perspective on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis—Prevalence, Clinical Impact, Economic Implications and Management Strategies. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tilg, H. NAFLD and Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Clinical Associations, Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Pharmacological Implications. Gut 2020, 69, 1691–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, F.; Almukhtar, M.; Fazlollahpour-Naghibi, A.; Alizadeh, F.; Behzad Moghadam, K.; Jafari Tadi, M.; Ghadimi, S.; Bagheri, K.; Babaei, H.; Bijani, M.H.; et al. Hepatitis C Infection Seroprevalence in Pregnant Women Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 66, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, I.; Rekacewicz, C.; El Hosseiny, M.; Ismail, S.; El Daly, M.; El-Kafrawy, S.; Esmat, G.; Hamid, M.A.; Mohamed, M.K.; Fontanet, A. Higher Clearance of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Females Compared with Males. Gut 2006, 55, 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroffolini, T.; Stroffolini, G. Prevalence and Modes of Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Historical Worldwide Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamosas-Falcón, L.; Probst, C.; Buckley, C.; Jiang, H.; Lasserre, A.M.; Puka, K.; Tran, A.; Rehm, J. Sex-Specific Association between Alcohol Consumption and Liver Cirrhosis: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Gastroenterol. 2022, 1, 1005729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrache (Păunescu), A.; Ionescu (Șuțan), N.A.; Țânțu, M.M.; Ponepal, M.C.; Soare, L.C.; Țânțu, A.C.; Atamanalp, M.; Baniță, I.M.; Pisoschi, C.G. Evaluating the Discriminative Performance of Noninvasive Biomarkers in Chronic Hepatitis B/C, Alcoholic Cirrhosis, and Nonalcoholic Cirrhosis: A Comparative Analysis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genowska, A.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Dobrowolska, K.; Kanecki, K.; Goryński, P.; Tyszko, P.; Lewtak, K.; Rzymski, P.; Flisiak, R. Trends in Hospitalizations of Patients with Hepatitis C Virus in Poland between 2012 and 2022. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talić Drlje, I.; Šušak, B.; Skočibušić, S.; Tutiš, B.; Jakovac, S.; Arapović, J. Sociodemographic Characteristics, Risk Factors and Genotype Distribution of Hepatitis C Virus in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Single Center Experience. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2025, 31, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, J.; Ayer, T.; Bethea, E.D.; Tapper, E.B.; Chhatwal, J. Projected Prevalence and Mortality Associated with Alcohol-Related Liver Disease in the USA, 2019–2040: A Modelling Study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e316–e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirode, G.; Saab, S.; Wong, R.J. Trends in the Burden of Chronic Liver Disease Among Hospitalized US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e201997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Hu, W.; Fang, T. The Global Impact of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (Including Cirrhosis) in the Elderly from 1990 to 2021 and Future Projections of Disease Burden. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliaz, R.; Yuce, T.; Torun, S.; Cavus, B.; Gulluoglu, M.; Bozaci, M.; Karaca, C.; Akyuz, F.; Demir, K.; Besisik, F.; et al. Changing Epidemiology of Chronic Hepatitis C: Patients Are Older and at a More Advanced Stage at the Time of Diagnosis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 31, 1247–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narro, G.E.C.; Díaz, L.A.; Ortega, E.K.; Garín, M.F.B.; Reyes, E.C.; Delfin, P.S.M.; Arab, J.P.; Bataller, R. Alcohol-Related Liver Disease: A Global Perspective. Ann. Hepatol. 2024, 29, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Feng, A.; Ma, W.; Li, D.; Zheng, S.; Xu, F.; Han, D.; Lyu, J. Worldwide Long-Term Trends in the Incidence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease during 1990–2019: A Joinpoint and Age-Period-Cohort Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 891963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, T.; Seki, K.; Umemura, A.; Ogawa, R.; Horimoto, R.; Oya, H.; Sendo, R.; Mizuno, M.; Okanoue, T. Influence of Lifestyle-related Diseases and Age on the Development and Progression of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatol. Res. 2015, 45, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.-J.; Lee, D.H.; Chang, Y.; Jo, H.; Cho, Y.Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, L.Y.; Jang, J.Y.; The Korean Association for the Study of the Liver. Trends in Alcohol Use and Alcoholic Liver Disease in South Korea: A Nationwide Cohort Study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danpanichkul, P.; Ng, C.H.; Tan, D.J.H.; Wijarnpreecha, K.; Huang, D.Q.; Noureddin, M.; Nah, B.; Koh, J.H.; Teng, M.; Lim, W.H.; et al. The Global Burden of Alcohol-Associated Cirrhosis and Cancer in Young and Middle-Aged Adults. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 1947–1949.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, C.; Chen, W.; Yao, K.; Sun, T.; Wang, J. Global, Regional, and National Burdens of Alcohol-Related Cirrhosis among Women from 1992 to 2021 and Its Predictions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Dong, Y.; Li, X.; Shao, W.; Wang, G.; Wu, H.; Chang, X. TACE-HAIC versus HAIC Combined with TKIs and ICIs for Hepatocellular Carcinoma with a High Tumor Burden—A Propensity-Score Matching Comparative Study. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1664756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasjim, B.J.; Mohammadi, M.; Balbale, S.N.; Paukner, M.; Banea, T.; Shi, H.; Furmanchuk, A.; VanWagner, L.B.; Zhao, L.; Duarte-Rojo, A.; et al. High Hospitalization Rates and Risk Factors Among Frail Patients with Cirrhosis: A 10-Year Population-Based Cohort Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 23, 1152–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinsson, A.; Zolopa, C.; Vakili, F.; Udhesister, S.; Kronfli, N.; Maheu-Giroux, M.; Bruneau, J.; Valerio, H.; Bajis, S.; Read, P.; et al. Sex and Gender Differences in Hepatitis C Virus Risk, Prevention, and Cascade of Care in People Who Inject Drugs: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 72, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laswi, H.; Abusalim, A.-R.; Warraich, M.S.; Khoshbin, K.; Shaka, H. Trends and Outcomes of Alcoholic Liver Cirrhosis Hospitalizations in the Last Two Decades: Analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Gastroenterol. Res. 2022, 15, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Satija, M.; Chaudhary, A.; Singh, S.; Sharma, S.; Girdhar, S.; Gupta, V.K.; Bansal, P. Epidemiological Correlates of Hepatitis C Infection- A Case Control Analysis from a Tertiary Care Hospital. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 2099–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Tong, Y. Age and Gender Distribution of Hepatitis C Virus Prevalence and Genotypes of Individuals of Physical Examination in WuHan, Central China. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Cai, G.F.; Lv, H.K.; Xu, S.F.; Wang, Z.T.; Jiang, Z.G.; Hu, C.G.; Chen, Y.D. Factors Correlating to the Development of Hepatitis C Virus Infection among Drug Users—Findings from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-W.; Chang, H.-C.; Chang, S.-C.; Liaw, Y.-F.; Lin, S.-M.; Liu, C.-J.; Lee, S.-D.; Lin, C.-L.; Chen, P.-J.; Lin, S.-C.; et al. Role of Reproductive Factors in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Impact on Hepatitis B- and C-Related Risk. Hepatology 2003, 38, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.P.; Singh, M.; Prahraj, D.; Yadav, D.P.; Singh, A.; Uthansigh, K.; Pati, G.K. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): A Comparative Study of Clinico-Socio-Demographic Characteristics among Two Diverse Indian Population. Romanian Med. J. 2024, 71, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, C.; Malhotra, A.; Ranjan, P.; Vikram, N.K.; Dwivedi, S.N.; Singh, N.; Shalimar; Singh, V. Variation in Lifestyle-Related Behavior Among Obese Indian Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 655032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, K.; Azhari, H.; Charette, J.H.; Underwood, F.E.; King, J.A.; Afshar, E.E.; Swain, M.G.; Congly, S.E.; Kaplan, G.G.; Shaheen, A.-A. The Prevalence and Incidence of NAFLD Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, M.H.; Yeo, Y.H.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Zou, B.; Wu, Y.; Ye, Q.; Huang, D.Q.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, J.; et al. 2019 Global NAFLD Prevalence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 2809–2817.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruf, A.; Dirchwolf, M.; Freeman, R.B. From Child-Pugh to MELD Score and beyond: Taking a Walk down Memory Lane. Ann. Hepatol. 2022, 27, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, E. Prognostic Models Including the Child–Pugh, MELD and Mayo Risk Scores—Where Are We and Where Should We Go? J. Hepatol. 2004, 41, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, A.; Farhan, M.; Inam, Q.; Rehman, S.; Zehra, S.R.; Shoaib, A.; Saghit, N.A. Analysis of Hepatic Function Markers in Chronic Liver Disease Patients According to Child-Pugh Classifications. J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2024, 67, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, A.R.; Moorthy, S. A Comparative Analysis between Model for End-Stage Liver Disease Score (MELD), Modified Model for End-Stage Liver Disease Score (MELD-Na), and Child–Pugh Score (CPS) in Predicting Complications among Cirrhosis Patients. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 37, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Qi, X.; Guo, X. Child–Pugh Versus MELD Score for the Assessment of Prognosis in Liver Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Medicine 2016, 95, e2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, I.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Talukder, S.; Akhter, R.; Das, A.; Nasrin, S. Child-Pugh Score of Decompensated Chronic Liver Disease Patient as a Predictor of Short-Term Prognosis. SAS J. Med. 2022, 8, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Fernandez, A.; Banerjee, R.; Thomaides-Brears, H.; Telford, A.; Sanyal, A.; Neubauer, S.; Nichols, T.E.; Raman, B.; McCracken, C.; Petersen, S.E.; et al. Liver Disease Is a Significant Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Outcomes—A UK Biobank Study. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hadi, H.; Di Vincenzo, A.; Vettor, R.; Rossato, M. Relationship between Heart Disease and Liver Disease: A Two-Way Street. Cells 2020, 9, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, N.S.; Basu, E.; Hwang, M.J.; Rosenblatt, R.; VanWagner, L.B.; Lim, H.I.; Murthy, S.B.; Kamel, H. Management of Stroke in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease: A Practical Review. Stroke 2023, 54, 2461–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipupo, S.O.; Ezenabor, E.H.; Ojo, A.B.; Ogunlakin, A.D.; Ojo, O.A. Interplay of the Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Diabetes Mellitus, and Inflammation: A Growing Threat to Public Health. Obes. Med. 2025, 55, 100613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Gu, C. Epidemiological Transition of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease-Related Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis: A Comparative Study between China and the Global Population (1990–2021). Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1624440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecani, M.; Andreozzi, P.; Cangemi, R.; Corica, B.; Miglionico, M.; Romiti, G.F.; Stefanini, L.; Raparelli, V.; Basili, S. Metabolic Syndrome and Liver Disease: Re-Appraisal of Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment Through the Paradigm Shift from NAFLD to MASLD. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cariou, B.; Byrne, C.D.; Loomba, R.; Sanyal, A.J. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease as a Metabolic Disease in Humans: A Literature Review. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021, 23, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Nalli, G.; Baratta, F.; Desideri, G.; Savoia, C. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Silent Driver of Cardiovascular Risk and a New Target for Intervention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, N.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Heterogeneous Pathomechanisms and Effectiveness of Metabolism-Based Treatment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wei, W. Ascites Complications Risk Factors of Decompensated Cirrhosis Patients: Logistic Regression and Prediction Model. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, C.; Clària, J.; Szabo, G.; Bosch, J.; Bernardi, M. Pathophysiology of Decompensated Cirrhosis: Portal Hypertension, Circulatory Dysfunction, Inflammation, Metabolism and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, S49–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkić, N.; Jovanović, P.; Barišić Jaman, M.; Selimović, N.; Paštrović, F.; Grgurević, I. Machine Learning for Short-Term Mortality in Acute Decompensation of Liver Cirrhosis: Better than MELD Score. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdish, R.K.; Roy, A.; Kumar, K.; Premkumar, M.; Sharma, M.; Rao, P.N.; Reddy, D.N.; Kulkarni, A.V. Pathophysiology and Management of Liver Cirrhosis: From Portal Hypertension to Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1060073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalekos, G.; Gatselis, N.; Drenth, J.P.; Heneghan, M.; Jørgensen, M.; Lohse, A.W.; Londoño, M.; Muratori, L.; Papp, M.; Samyn, M.; et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, 453–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebayo, D.; Neong, S.F.; Wong, F. Ascites and Hepatorenal Syndrome. Clin. Liver Dis. 2019, 23, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, M.; Napolitano, C.; Vaia, P.; Di Nardo, F.; Borrelli, S.; Garofalo, C.; De Nicola, L.; Federico, A.; Dallio, M. Managing Ascites and Kidney Dysfunction in Decompensated Advanced Chronic Liver Disease: From “One Size Fits All” to a Multidisciplinary-Tailored Approach. Livers 2025, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gaetano, V.; Pallozzi, M.; Cerrito, L.; Santopaolo, F.; Stella, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ponziani, F.R. Management of Portal Hypertension in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma on Systemic Treatment: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2024, 16, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinter, M.; Trauner, M.; Peck-Radosavljevic, M.; Sieghart, W. Cancer and Liver Cirrhosis: Implications on Prognosis and Management. ESMO Open 2016, 1, e000042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlallah, H.; El Masri, D.; Bahmad, H.F.; Abou-Kheir, W.; El Masri, J. Update on the Complications and Management of Liver Cirrhosis. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanai, F.; Alghamdi, H.; Alswat, K.; Babatin, M.; Ismail, M.; Alhamoudi, W.; Alalwan, A.; Dahlan, Y.; Alghamdi, A.; Alfaleh, F.; et al. Greater Prevalence of Comorbidities with Increasing Age: Cross-Sectional Analysis of Chronic Hepatitis B Patients in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primary Diagnosis | Indicator | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Overall (2019–2023) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHC | Pearson χ2 | 124.91 | 48.25 | 61.81 | 98.13 | 71.04 | 382.24 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Gamma | 0.518 | 0.484 | 0.521 | 0.571 | 0.596 | 0.535 | |

| ALH | Pearson χ2 | 132.35 | 47.34 | 40.15 | 70.41 | 51.00 | 323.04 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Gamma | −0.537 | −0.508 | −0.473 | −0.571 | −0.545 | −0.525 | |

| NALC | Pearson χ2 | 18.96 | 14.75 | 10.68 | 29.02 | 12.95 | 56.98 |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.022 | 0.099 | 0.000 | 0.044 | 0.000 | |

| Gamma | −0.040 | −0.213 | −0.111 | 0.016 | −0.117 | −0.080 | |

| ALC | Pearson χ2 | 27.40 | 5.85 | 11.18 | 15.03 | 14.88 | 60.58 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.440 | 0.083 | 0.020 | 0.021 | <0.001 | |

| Gamma | −0.353 | −0.232 | −0.242 | −0.420 | −0.422 | −0.337 | |

| Valid N | 888 | 365 | 356 | 409 | 341 | 2359 |

| Primary Diagnosis | Year | Mean ± SD | Median | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHC | 2019 | 13.80 ± 15.71 | 9 | 1–147 | 3.58 | 19.40 | 12.76–14.83 |

| 2020 | 10.55 ± 11.51 | 7 | 1–137 | 5.28 | 47.06 | 9.37–11.74 | |

| 2021 | 10.47 ± 9.17 | 8 | 1–62 | 2.33 | 7.28 | 9.52–11.43 | |

| 2022 | 10.97 ± 12.05 | 8 | 1–164 | 6.18 | 66.00 | 9.80–12.14 | |

| 2023 | 9.10 ± 7.95 | 7 | 1–62 | 2.73 | 11.37 | 8.25–9.95 | |

| ALH | 2019 | 14.22 ± 15.88 | 10 | 1–147 | 3.70 | 18.95 | 13.18–15.27 |

| 2020 | 11.87 ± 11.82 | 8 | 1–137 | 5.01 | 46.10 | 10.57–13.17 | |

| 2021 | 11.46 ± 9.65 | 8 | 1–62 | 2.61 | 8.54 | 10.45–12.47 | |

| 2022 | 12.13 ± 12.47 | 8 | 1–164 | 6.25 | 65.84 | 10.93–13.33 | |

| 2023 | 10.11 ± 8.22 | 7 | 1–62 | 2.85 | 12.15 | 9.21–11.01 | |

| NALC | 2019 | 15.26 ± 16.12 | 10 | 1–147 | 3.75 | 21.14 | 14.10–16.42 |

| 2020 | 12.02 ± 12.10 | 8 | 1–137 | 5.14 | 48.32 | 10.70–13.34 | |

| 2021 | 11.73 ± 9.74 | 8 | 1–62 | 2.59 | 9.22 | 10.70–12.76 | |

| 2022 | 12.84 ± 12.52 | 9 | 1–164 | 6.34 | 67.01 | 11.63–14.05 | |

| 2023 | 10.56 ± 8.31 | 7 | 1–62 | 2.91 | 12.40 | 9.66–11.46 | |

| ALC | 2019 | 16.81 ± 17.04 | 11 | 1–147 | 3.93 | 22.68 | 15.60–18.02 |

| 2020 | 13.24 ± 13.12 | 9 | 1–137 | 5.22 | 49.15 | 11.90–14.58 | |

| 2021 | 12.68 ± 10.11 | 9 | 1–62 | 2.75 | 9.86 | 11.61–13.75 | |

| 2022 | 13.97 ± 12.94 | 9 | 1–164 | 6.40 | 68.12 | 12.74–15.20 | |

| 2023 | 11.24 ± 8.54 | 8 | 1–62 | 3.02 | 12.93 | 10.33–12.15 |

| Predictor | B * | Std. Error | 95% CI | Wald χ2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.245 | 0.141 | 3.970–4.521 | 912.37 | <0.001 |

| CHC (yes vs. no) | Reference | - | - | - | - |

| CHC (no vs. yes) | −0.784 | 0.062 | −0.904–−0.663 | 162.39 | <0.001 |

| ALH (no vs. yes) | −0.750 | 0.051 | −0.850–−0.651 | 220.10 | <0.001 |

| NALC (no vs. yes) | −0.940 | 0.048 | −1.034–−0.846 | 381.24 | <0.001 |

| ALC (no vs. yes) | −0.626 | 0.052 | −0.728–−0.524 | 144.33 | <0.001 |

| Child–Pugh | 0.007 | 0.022 | −0.036–0.051 | 0.112 | 0.738 |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 0.040 | 0.040 | −0.038–0.118 | 1.021 | 0.312 |

| Age | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001–0.007 | 8.776 | 0.003 |

| Diagnostic | Child–Pugh A | Child–Pugh B | Child–Pugh C | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHC | No | 708 (30.0%) | 363 (15.4%) | 317 (13.6%) | 1389 (59%) |

| Yes | 886 (37.6%) | 42 (1.8%) | 41 (1.7%) | 969 (41.1%) | |

| ALH | No | 1104 (46.8%) | 165 (7.0%) | 136 (5.8%) | 1405 (59.6%) |

| Yes | 491 (20.8%) | 240 (10.2%) | 222 (9.4%) | 954 (40.4%) | |

| NALC | No | 1277 (54.1%) | 252 (10.7%) | 226 (9.6%) | 1756 (74.4%) |

| Yes | 318 (13.5%) | 153 (6.5%) | 132 (5.6%) | 603 (25.6%) | |

| ALC | No | 1463 (91.7%) | 341 (84.2%) | 294 (82.2%) | 2099 (89.1%) |

| Yes | 132 (8.3%) | 64 (15.8%) | 64 (17.9%) | 260 (11.0%) | |

| Child–Pugh | Predictor | B | SE | Wald | df | p | Exp(B) | 95% CI (Lower-Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | CHC | −1.753 | 0.218 | 64.834 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.173 | 0.113–0.266 |

| EV | 0.393 | 0.124 | 10.066 | 1 | 0.002 | 1.481 | 1.162–1.888 | |

| HE | 0.483 | 0.149 | 10.509 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.620 | 1.210–2.169 | |

| HRS | 0.327 | 0.160 | 4.202 | 1 | 0.040 | 1.387 | 1.014–1.897 | |

| PH | 1.124 | 0.133 | 71.805 | 1 | 0.000 | 3.078 | 2.373–3.993 | |

| B | Sex | 0.192 | 0.164 | 1.376 | 1 | 0.241 | 1.211 | 0.879–1.669 |

| Year | reference | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| CHC | 1.797 | 0.273 | 43.286 | 1 | 0.000 | 6.031 | 3.531–10.301 | |

| ALH | 0.319 | 0.194 | 2.721 | 1 | 0.099 | 1.376 | 0.942–2.011 | |

| NALC | 0.163 | 0.191 | 0.730 | 1 | 0.393 | 1.177 | 0.810–1.710 | |

| ALC | 0.172 | 0.177 | 0.951 | 1 | 0.329 | 1.188 | 0.840–1.680 | |

| CVA | 0.357 | 0.328 | 1.189 | 1 | 0.276 | 1.429 | 0.752–2.716 | |

| HF | 0.146 | 0.208 | 0.497 | 1 | 0.481 | 1.158 | 0.771–1.739 | |

| DM | −0.302 | 0.174 | 3.017 | 1 | 0.082 | 0.739 | 0.525–1.040 | |

| Ob | 0.345 | 0.326 | 1.124 | 1 | 0.289 | 1.412 | 0.746–2.673 | |

| EV | −0.484 | 0.137 | 12.563 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.616 | 0.471–0.805 | |

| DB | −0.028 | 0.197 | 0.020 | 1 | 0.887 | 0.972 | 0.660–1.431 | |

| HE | −0.184 | 0.163 | 1.269 | 1 | 0.260 | 0.832 | 0.605–1.146 | |

| HCC | 0.076 | 0.248 | 0.093 | 1 | 0.760 | 1.079 | 0.663–1.754 | |

| HRS | 0.328 | 0.191 | 2.948 | 1 | 0.086 | 1.388 | 0.955–2.019 | |

| PH | −0.772 | 0.164 | 22.106 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.462 | 0.335–0.638 | |

| Age groups | - | - | 5.210 | 6 | 0.517 | - | - | |

| Constant | −3.023 | 0.799 | 14.332 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.049 | - | |

| C | Sex | −0.115 | 0.170 | 0.454 | 1 | 0.500 | 0.892 | 0.639–1.244 |

| CHC | 1.115 | 0.274 | 16.607 | 1 | 0.000 | 3.050 | 1.784–5.215 | |

| ALH | −0.045 | 0.199 | 0.051 | 1 | 0.822 | 0.956 | 0.647–1.413 | |

| NALC | 0.042 | 0.194 | 0.047 | 1 | 0.829 | 1.043 | 0.713–1.526 | |

| ALC | −0.128 | 0.179 | 0.509 | 1 | 0.476 | 0.880 | 0.619–1.251 | |

| CVA | 0.071 | 0.335 | 0.046 | 1 | 0.831 | 1.074 | 0.558–2.069 | |

| HF | 0.331 | 0.230 | 2.072 | 1 | 0.150 | 1.392 | 0.887–2.185 | |

| DM | −0.076 | 0.188 | 0.165 | 1 | 0.685 | 0.926 | 0.641–1.340 | |

| Ob | −0.199 | 0.313 | 0.404 | 1 | 0.525 | 0.819 | 0.443–1.514 | |

| EV | −0.010 | 0.147 | 0.005 | 1 | 0.943 | 0.990 | 0.742–1.319 | |

| DB | −0.302 | 0.201 | 2.264 | 1 | 0.132 | 0.739 | 0.499–1.096 | |

| HE | −0.426 | 0.165 | 6.666 | 1 | 0.010 | 0.653 | 0.473–0.903 | |

| HCC | −0.090 | 0.263 | 0.117 | 1 | 0.733 | 0.914 | 0.546–1.530 | |

| HRS | −0.691 | 0.170 | 16.480 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.501 | 0.359–0.699 | |

| PH | −1.055 | 0.183 | 33.325 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.348 | 0.244–0.498 | |

| Age groups | - | - | 7.727 | 6 | 0.259 | - | - | |

| Constant | −1.465 | 0.906 | 2.617 | 1 | 0.106 | 0.231 | - |

| Observed | Predicted | Corectly Classified (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Child–Pugh A | 0.00 | 451 | 312 | 59.1 |

| 1.00 | 311 | 1285 | 80.5 | |

| Overall percentage | 73.6 | |||

| Child–Pugh B | 0.00 | 1954 | 3 | 99.8 |

| 1.00 | 405 | 0 | 0 | |

| Overall percentage | 82.7 | |||

| Child–Pugh B | 0.00 | 1998 | 3 | 99.9 |

| 1.00 | 347 | 11 | 3.1 | |

| Overall percentage | 85.2 | |||

| Variable | Category | Child–Pugh A | Child–Pugh B | Child–Pugh C | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 701 (29.7%) | 74 (3.1%) | 73 (3.1%) | 848 (36.0%) |

| Male | 893 (37.9%) | 331 (14.0%) | 285 (12.1%) | 1510 (64.0%) | |

| Year | 2019 | 638 (27.1%) | 141 (6.0%) | 107 (4.6%) | 887 (37.7%) |

| 2020 | 251 (10.6%) | 55 (2.3%) | 59 (2.5%) | 365 (15.5%) | |

| 2021 | 226 (9.6%) | 63 (2.7%) | 67 (2.8%) | 356 (15.1%) | |

| 2022 | 249 (10.6%) | 90 (3.8%) | 70 (3.0%) | 409 (17.3%) | |

| 2023 | 230 (9.8%) | 56 (2.4%) | 55 (2.3%) | 341 (14.5%) | |

| Age group | ≤30 | 4 (0.2%) | 3 (0.1%) | 2 (0.2%) | 10 (0.5%) |

| 31–40 | 61 (2.6%) | 18 (0.8%) | 20 (0.8%) | 99 (4.2%) | |

| 41–50 | 208 (8.8%) | 83 (3.5%) | 67 (2.8%) | 358 (15.2%) | |

| 51–60 | 352 (14.9%) | 106 (4.5%) | 118 (5.0%) | 576 (24.4%) | |

| 61–70 | 494 (20.9%) | 135 (5.7%) | 103 (4.4%) | 732 (31.0%) | |

| 71–80 | 324 (13.7%) | 45 (1.9%) | 44 (1.9%) | 413 (17.5%) | |

| ≥81 | 151 (6.4%) | 15 (0.6%) | 4 (0.2%) | 170 (7.2%) |

| Source | df | F | Sig. | Partial η2 | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 14 | 2.266 | 0.005 | 0.013 | Significant overall model |

| Intercept | 1 | 9.926 | 0.002 | 0.004 | Constant effect significant |

| CHC | 1 | 0.047 | 0.829 | 0.000 | n.s. * |

| ALH | 1 | 2.756 | 0.097 | 0.001 | Trend-level effect |

| NALC | 1 | 0.042 | 0.838 | 0.000 | n.s. |

| ALC | 1 | 0.265 | 0.607 | 0.000 | n.s. |

| YEAR_min | 1 | 0.000 | 0.987 | 0.000 | n.s. |

| CHC × YEAR | 1 | 0.608 | 0.436 | 0.000 | n.s. |

| ALH × YEAR | 1 | 1.675 | 0.196 | 0.001 | n.s. |

| ALH × NALC | 1 | 1.810 | 0.179 | 0.001 | n.s. |

| ALH × NALC × ALC × YEAR | 6 | 0.541 | 0.777 | 0.001 | n.s. |

| Comorbidity | Year | Negative n (%) | Positive n (%) | Total n | χ2 (df) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVA | 2019 | 827 (93.1%) | 61 (6.9%) | 888 | 8.793 (4) | 0.066 |

| 2020 | 347 (95.1%) | 18 (4.9%) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 341 (95.8%) | 15 (4.2%) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 393 (96.1%) | 16 (3.9%) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 315 (92.4%) | 26 (7.6%) | 341 | |||

| HF | 2019 | 695 (78.3%) | 193 (21.7%) | 888 | 20.710 (4) | <0.001 |

| 2020 | 296 (81.1%) | 69 (18.9%) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 301 (84.6%) | 55 (15.4%) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 321 (78.5%) | 88 (21.5%) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 301 (88.3%) | 40 (11.7%) | 341 | |||

| DM | 2019 | 735 (82.8%) | 153 (17.2%) | 888 | 4.046 (4) | 0.400 |

| 2020 | 298 (81.6%) | 67 (18.4%) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 302 (84.8%) | 54 (15.2%) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 351 (85.8%) | 58 (14.2%) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 291 (85.3%) | 50 (14.7%) | 341 | |||

| Ob | 2019 | 821 (92.5%) | 67 (7.5%) | 888 | 9.135 (4) | 0.058 |

| 2020 | 342 (93.7%) | 23 (6.3%) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 341 (95.8%) | 15 (4.2%) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 393 (96.1%) | 16 (3.9%) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 318 (93.3%) | 23 (6.7%) | 341 |

| Comorbidity | Age (Years) | Total Prevalence | Chi-Square (p-Value) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–60 | 61–70 | 71–80 | ≥81 | |||

| CVA | 0% | 1.0% | 1.4% | 4.9% | 6.3% | 8.0% | 13.5% | 5.8% | 41.224 (<0.001) |

| HF | 0% | 2.0% | 3.9% | 13.5% | 19.0% | 29.8% | 52.4% | 18.9% | 240.610 (<0.001) |

| DM | 10.0% | 3.0% | 10.3% | 12.0% | 18.3% | 25.4% | 19.4% | 16.2% | 59.333 (<0.001) |

| Ob | 12.0% | 14.0% | 16.0% | 20.0% | 22.0% | 27.5% | 15.0% | 19.0% | 38.500 (<0.001) |

| Complication | Group | Count | % (Group N/Subgroup) | χ2 (df = 1) | p-Value (Two-Sided) | Cramér’s V (√(χ2/N)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVA | Total (N = 2359) | 136 | 5.77% | 16.474 | <0.001 | 0.083 |

| Female (n = 849) | 71 | 8.36% | ||||

| Male (n = 1510) | 65 | 4.31% | ||||

| HF | Total (N = 2359) | 445 | 18.86% | 74.739 | <0.001 | 0.178 |

| Female (n = 849) | 239 | 28.15% | ||||

| Male (n = 1510) | 206 | 13.64% | ||||

| DM | Total (N = 2359) | 382 | 16.19% | 14.338 | <0.001 | 0.078 |

| Female (n = 849) | 170 | 20.02% | ||||

| Male (n = 1510) | 212 | 14.04% | ||||

| Ob | Total (N = 2359) | 144 | 6.10% | 18.762 | <0.001 | 0.089 |

| Female (n = 849) | 76 | 8.95% | ||||

| Male (n = 1510) | 68 | 4.50% |

| Comorbidity | Year | Negative n (%) | Positive n (%) | Total n | Chi-Square (df) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascites | 2019 | 626 (70.5) | 262 (29.5) | 888 | 12.247 (4) | 0.016 |

| 2020 | 247 (67.7) | 118 (32.3) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 218 (61.2) | 138 (38.8) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 261 (63.8) | 148 (36.2) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 230 (67.4) | 111 (32.6) | 341 | |||

| EV | 2019 | 680 (76.6) | 208 (23.4) | 888 | 40.050 (4) | <0.001 |

| 2020 | 276 (75.6) | 89 (24.4) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 271 (76.1) | 85 (23.9) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 277 (67.7) | 132 (32.3) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 298 (87.4) | 43 (12.6) | 341 | |||

| DB | 2019 | 800 (90.1) | 88 (9.9) | 888 | 38.860 (4) | <0.001 |

| 2020 | 326 (89.3) | 39 (10.7) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 299 (84.0) | 57 (16.0) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 386 (94.4) | 23 (5.6) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 328 (96.2) | 13 (3.8) | 341 | |||

| HE | 2019 | 809 (91.1) | 79 (8.9) | 888 | 30.742 (4) | <0.001 |

| 2020 | 331 (90.7) | 34 (9.3) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 309 (86.8) | 47 (13.2) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 331 (80.9) | 78 (19.1) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 298 (87.4) | 43 (12.6) | 341 | |||

| HCC | 2019 | 810 (91.2) | 78 (8.8) | 888 | 16.470 (4) | 0.002 |

| 2020 | 346 (94.8) | 19 (5.2) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 344 (96.6) | 12 (3.4) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 386 (94.4) | 23 (5.6) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 324 (95.0) | 17 (5.0) | 341 | |||

| HRS | 2019 | 802 (90.3) | 86 (9.7) | 888 | 0.985 (4) | 0.912 |

| 2020 | 331 (90.7) | 34 (9.3) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 325 (91.3) | 31 (8.7) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 365 (89.2) | 44 (10.8) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 308 (90.3) | 33 (9.7) | 341 | |||

| PH | 2019 | 412 (46.4) | 476 (53.6) | 888 | 16.075 (4) | 0.003 |

| 2020 | 178 (48.8) | 187 (51.2) | 365 | |||

| 2021 | 151 (42.4) | 205 (57.6) | 356 | |||

| 2022 | 159 (38.9) | 250 (61.1) | 409 | |||

| 2023 | 177 (51.9) | 164 (48.1) | 341 |

| Complication | Age (Years) | Total Positive (%) | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–60 | 61–70 | 71–80 | ≥81 | |||

| Ascites | 30.0% | 26.0% | 39.9% | 38.7% | 36.9% | 22.5% | 11.2% | 777 (32.9%) | <0.001 |

| EV | 30.0% | 26.0% | 31.3% | 26.7% | 23.1% | 18.6% | 9.4% | 557 (23.6%) | <0.001 |

| DB | 0.0% | 7.0% | 12.8% | 9.4% | 10.0% | 8.0% | 4.1% | 220 (9.3%) | 0.034 |

| HE | 0.0% | 14.0% | 12.6% | 13.2% | 11.6% | 12.3% | 5.9% | 281 (11.9%) | 0.182 |

| HCC | 0.0% | 3.0% | 5.6% | 6.4% | 6.7% | 7.7% | 4.7% | 149 (6.3%) | 0.516 |

| HRS | 10.0% | 12.0% | 8.7% | 12.2% | 10.1% | 8.7% | 2.4% | 228 (9.7%) | 0.013 |

| PH | 80.0% | 69.0% | 72.1% | 62.7% | 55.1% | 37.0% | 17.6% | 1282 (54.3%) | <0.001 |

| Complication | Female (%) | Male (%) | Total Prevalence (%) | χ2 (df = 1) | p-Value | Effect Size (Cramer’s V) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascites | 23.4 | 38.3 | 32.9 | 54.17 | <0.001 | 0.152 | Moderate, males > females |

| EV | 18.4 | 26.6 | 23.6 | 20.17 | <0.001 | 0.093 | Weak, males > females |

| DB | 8.2 | 9.9 | 9.3 | 1.83 | 0.176 | 0.028 | n.s. |

| HE | 7.1 | 14.6 | 11.9 | 29.67 | <0.001 | 0.112 | Weak, males > females |

| HCC | 5.2 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 2.88 | 0.090 | 0.035 | n.s. (trend) |

| HRS | 6.0 | 11.7 | 9.7 | 20.33 | <0.001 | 0.093 | Weak, males > females |

| PH | 32.2 | 66.8 | 54.3 | 263.21 | <0.001 | 0.334 | Strong, males > females |

| Diagnosis Group | Status | N | Mean | Median | SD | Variance | Range | IQR | Skewness | Kurtosis | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHC | No | 2718 | 3.74 | 2 | 3.67 | 13.47 | 18 | 4 | 1.99 | 3.91 | 1 | 19 |

| CHC | Yes | 1622 | 3.99 | 2 | 5.39 | 29.03 | 30 | 4 | 3.20 | 11.57 | 1 | 31 |

| ALH | No | 3045 | 4.25 | 2 | 4.88 | 23.77 | 30 | 4 | 2.75 | 9.56 | 1 | 31 |

| ALH | Yes | 1295 | 2.86 | 2 | 2.72 | 7.41 | 16 | 2 | 2.16 | 5.08 | 1 | 17 |

| NALC | No | 3211 | 3.74 | 2 | 4.50 | 20.25 | 30 | 4 | 2.91 | 11.11 | 1 | 31 |

| NALC | Yes | 1129 | 4.17 | 3 | 5.39 | 29.03 | 30 | 6.5 | 3.20 | 11.57 | 1 | 19 |

| ALC | No | 4046 | 3.89 | 2 | 4.50 | 20.25 | 30 | 4 | 2.91 | 11.11 | 1 | 31 |

| ALC | Yes | 294 | 3.10 | 2 | 2.36 | 5.59 | 14 | 2 | 2.03 | 4.99 | 1 | 15 |

| Age Group (Years) | N Patients | Mean ± SE | Median | SD | Min–Max | IQR | Skewness | 95% CI Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤30 | 17 | 2.12 ± 0.26 | 2 | 1.05 | 1–4 | 2 | 0.47 | 1.67–2.63 |

| 31–40 | 158 | 2.77 ± 0.18 | 2 | 2.31 | 1–9 | 3 | 1.40 | 2.43–3.15 |

| 41–50 | 644 | 3.24 ± 0.10 | 2 | 2.65 | 1–15 | 3 | 1.41 | 3.04–3.45 |

| 51–60 | 1139 | 4.38 ± 0.14 | 3 | 4.55 | 1–19 | 5 | 1.72 | 4.14–4.66 |

| 61–70 | 1386 | 3.66 ± 0.09 | 2 | 3.47 | 1–19 | 4 | 1.84 | 3.47–3.85 |

| 71–80 | 732 | 3.33 ± 0.14 | 2 | 3.65 | 1–22 | 3 | 2.90 | 3.05–3.59 |

| ≥81 | 265 | 6.04 ± 0.61 | 1 | 9.95 | 1–31 | 3 | 1.93 | 4.83–7.28 |

| Sex | N | Mean ± SE | 95% CI Mean | Median | 5% Trimmed Mean | SD | Variance | Min– Max | Range | IQR | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 1582 | 4.19 ± 0.13 | 3.92–4.47 | 2 | 3.31 | 5.34 | 28.55 | 1–31 | 30 | 4 | 3.18 | 11.72 |

| Male | 2759 | 3.63 ± 0.07 | 3.49–3.77 | 2 | 3.11 | 3.73 | 13.90 | 1–19 | 18 | 3 | 2.08 | 4.27 |

| Primary Diagnostic | N | Mean * (±SE) | 95% CI | Min–Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHC | 1622 | 3.99 ± 0.13 | 3.73–4.26 | 1–31 |

| ALH | 1295 | 2.86 ± 0.08 | 2.71–3.01 | 1–17 |

| NALC | 1129 | 4.92 ± 0.13 | 4.66–5.18 | 1–19 |

| ALC | 294 | 3.10 ± 0.14 | 2.82–3.37 | 1–15 |

| Total | 4340 | 3.83 ± 0.07 | 3.70–3.97 | 1–31 |

| Variables | Number_ Hospitalizations | Age_Group | Sex | CHC | ALH | NALC | ALC | Arterial Hypertension | Cerebrovascular Accident | Heart Failure | Diabetes Mellitus | Obesity | Child-Pugh | Ascites | Esophageal Varices | Digestive Bleeding | Encephalopathy | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Hepatorenal Syndrome | Portal Hypertension |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number_ Hospitalizations | 1 | −0.048 ** | −0.02 | −0.066 ** | −0.133 ** | 0.206 ** | 0.01 | −0.122 ** | −0.092 ** | −0.072 ** | −0.038 * | −0.034 * | 0.079 ** | 0.206 ** | 0.091 ** | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.176 ** |

| Age_Group | −0.048 ** | 1 | −0.316 ** | 0.347 ** | −0.299 ** | −0.01 | −0.115 ** | 0.286 ** | 0.102 ** | 0.268 ** | 0.128 ** | 0.036 * | −0.172 ** | −0.109 ** | −0.072 ** | −0.039 * | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.226 ** |

| Sex | −0.02 | −0.316 ** | 1 | −0.521 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.160 ** | 0.120 ** | −0.210 ** | −0.063 ** | −0.164 ** | −0.088 ** | −0.061 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.160 ** | 0.048 ** | 0.01 | 0.100 ** | 0.042 ** | 0.076 ** | 0.303 ** |

| CHC | −0.066 ** | 0.347 ** | −0.521 ** | 1 | −0.504 ** | −0.458 ** | −0.208 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.072 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.160 ** | 0.100 ** | −0.404 ** | −0.339 ** | −0.113 ** | −0.01 | −0.132 ** | 0.01 | −0.150 ** | −0.543 ** |

| ALH | −0.133 ** | −0.299 ** | 0.331 ** | −0.504 ** | 1 | −0.387 ** | −0.176 ** | −0.160 ** | −0.041 ** | −0.168 ** | −0.087 ** | −0.069 ** | 0.185 ** | −0.131 ** | 0.075 ** | 0.00 | 0.066 ** | −0.01 | 0.073 ** | 0.275 ** |

| NALC | 0.206 ** | −0.01 | 0.160 ** | −0.458 ** | −0.387 ** | 1 | −0.160 ** | −0.188 ** | −0.03 | −0.101 ** | −0.057 ** | −0.02 | 0.202 ** | 0.420 ** | 0.061 ** | 0.01 | 0.081 ** | 0.03 | 0.105 ** | 0.321 ** |

| ALC | 0.01 | −0.115 ** | 0.120 ** | −0.208 ** | −0.176 ** | −0.160 ** | 1 | −0.092 ** | −0.02 | −0.059 ** | −0.051 ** | −0.040 ** | 0.088 ** | 0.159 ** | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.049 ** | −0.03 | −0.02 |

| Arterial Hypertension | −0.122 ** | 0.286 ** | −0.210 ** | 0.369 ** | −0.160 ** | −0.188 ** | −0.092 ** | 1 | 0.186 ** | 0.560 ** | 0.250 ** | 0.230 ** | −0.212 ** | −0.268 ** | −0.098 ** | −0.047 ** | −0.031 * | −0.01 | −0.079 ** | −0.309 ** |

| Cerebrovascular Accident | −0.092 ** | 0.102 ** | −0.063 ** | 0.072 ** | −0.041 ** | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.186 ** | 1 | 0.208 ** | 0.086 ** | 0.039 * | −0.065 ** | −0.087 ** | −0.044 ** | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.089 ** |

| Heart Failure | −0.072 ** | 0.268 ** | −0.164 ** | 0.281 ** | −0.168 ** | −0.101 ** | −0.059 ** | 0.560 ** | 0.208 ** | 1 | 0.223 ** | 0.160 ** | −0.154 ** | −0.187 ** | −0.076 ** | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.054 ** | −0.238 ** |

| Diabetes Mellitus | −0.038 * | 0.128 ** | −0.088 ** | 0.160 ** | −0.087 ** | −0.057 ** | −0.051 ** | 0.250 ** | 0.086 ** | 0.223 ** | 1 | 0.125 ** | −0.059 ** | −0.110 ** | −0.052 ** | −0.030 * | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.126 ** |

| Obesity | −0.034 * | 0.036 * | −0.061 ** | 0.100 ** | −0.069 ** | −0.02 | −0.040 ** | 0.230 ** | 0.039 * | 0.160 ** | 0.125 ** | 1 | −0.044 ** | −0.074 ** | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.087 ** |

| Child-Pugh | 0.079 ** | −0.172 ** | 0.220 ** | −0.404 ** | 0.185 ** | 0.202 ** | 0.088 ** | −0.212 ** | −0.065 ** | −0.154 ** | −0.059 ** | −0.044 ** | 1 | 0.294 ** | 0.143 ** | 0.03 | 0.122 ** | −0.01 | 0.135 ** | 0.394 ** |

| Ascites | 0.206 ** | −0.109 ** | 0.160 ** | −0.339 ** | −0.131 ** | 0.420 ** | 0.159 ** | −0.268 ** | −0.087 ** | −0.187 ** | −0.110 ** | −0.074 ** | 0.294 ** | 1 | 0.084 ** | 0.050 ** | 0.03 | 0.031 * | 0.122 ** | 0.380 ** |

| Esophageal Varices | 0.091 ** | −0.072 ** | 0.048 ** | −0.113 ** | 0.075 ** | 0.061 ** | −0.02 | −0.098 ** | −0.044 ** | −0.076 ** | −0.052 ** | 0.00 | 0.143 ** | 0.084 ** | 1 | 0.258 ** | 0.126 ** | 0.02 | −0.030 * | 0.208 ** |

| Digestive Bleeding | 0.00 | −0.039 * | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.047 ** | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.030 * | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.050 ** | 0.258 ** | 1 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.045 ** |

| Encephalopathy | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.100 ** | −0.132 ** | 0.066 ** | 0.081 ** | −0.01 | −0.031 * | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.122 ** | 0.03 | 0.126 ** | 0.02 | 1 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.112 ** |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.042 ** | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.049 ** | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.031 * | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 1 | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| Hepatorenal Syndrome | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.076 ** | −0.150 ** | 0.073 ** | 0.105 ** | −0.03 | −0.079 ** | 0.00 | −0.054 ** | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.135 ** | 0.122 ** | −0.030 * | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 1 | 0.111 ** |

| Portal Hypertension | 0.176 ** | −0.226 ** | 0.303 ** | −0.543 ** | 0.275 ** | 0.321 ** | −0.02 | −0.309 ** | −0.089 ** | −0.238 ** | −0.126 ** | −0.087 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.380 ** | 0.208 ** | 0.045 ** | 0.112 ** | −0.01 | 0.111 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dumitrache, A.; Șuțan, N.A.; Popescu, D.I.; Soare, L.C.; Ponepal, M.C.; Mihăescu, C.F.; Bondoc, M.D.; Atamanalp, M.; Țânțu, A.C.; Pisoschi, C.G.; et al. A Retrospective Analysis of Hepatic Disease Burden and Progression in a Hospital-Based Romanian Cohort Using Integrated Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data (2019–2023). J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020454

Dumitrache A, Șuțan NA, Popescu DI, Soare LC, Ponepal MC, Mihăescu CF, Bondoc MD, Atamanalp M, Țânțu AC, Pisoschi CG, et al. A Retrospective Analysis of Hepatic Disease Burden and Progression in a Hospital-Based Romanian Cohort Using Integrated Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data (2019–2023). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020454

Chicago/Turabian StyleDumitrache (Păunescu), Alina, Nicoleta Anca Șuțan, Diana Ionela Popescu (Stegarus), Liliana Cristina Soare, Maria Cristina Ponepal, Cristina Florina Mihăescu, Maria Daniela Bondoc, Muhammed Atamanalp, Ana Cătălina Țânțu, Cătălina Gabriela Pisoschi, and et al. 2026. "A Retrospective Analysis of Hepatic Disease Burden and Progression in a Hospital-Based Romanian Cohort Using Integrated Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data (2019–2023)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020454

APA StyleDumitrache, A., Șuțan, N. A., Popescu, D. I., Soare, L. C., Ponepal, M. C., Mihăescu, C. F., Bondoc, M. D., Atamanalp, M., Țânțu, A. C., Pisoschi, C. G., Baniță, I. M., & Țânțu, M. M. (2026). A Retrospective Analysis of Hepatic Disease Burden and Progression in a Hospital-Based Romanian Cohort Using Integrated Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data (2019–2023). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020454