Portopulmonary Hypertension and Hepatopulmonary Syndrome: Contrasting Pathophysiology and Implications for Liver Transplantation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Consolidated Epidemiology

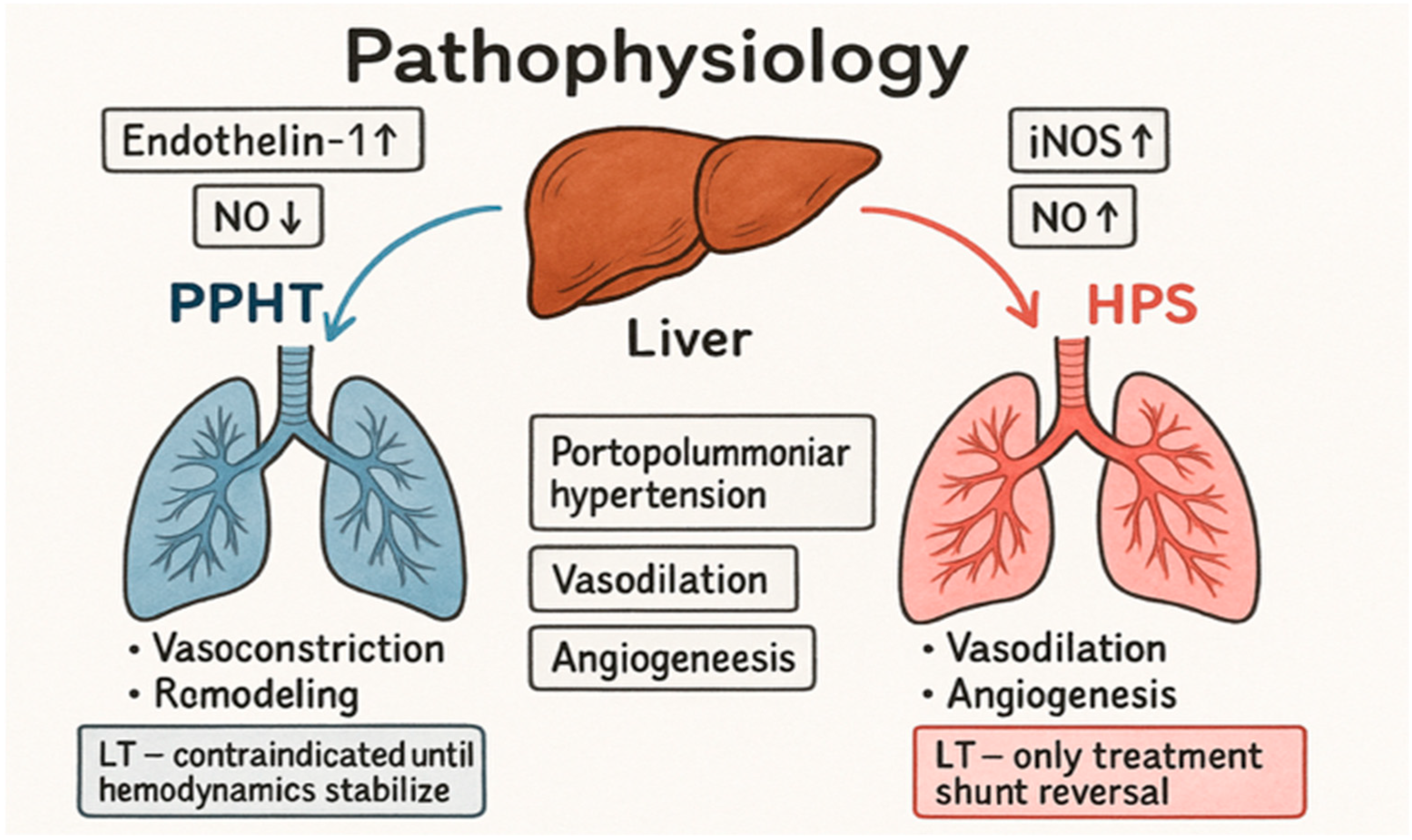

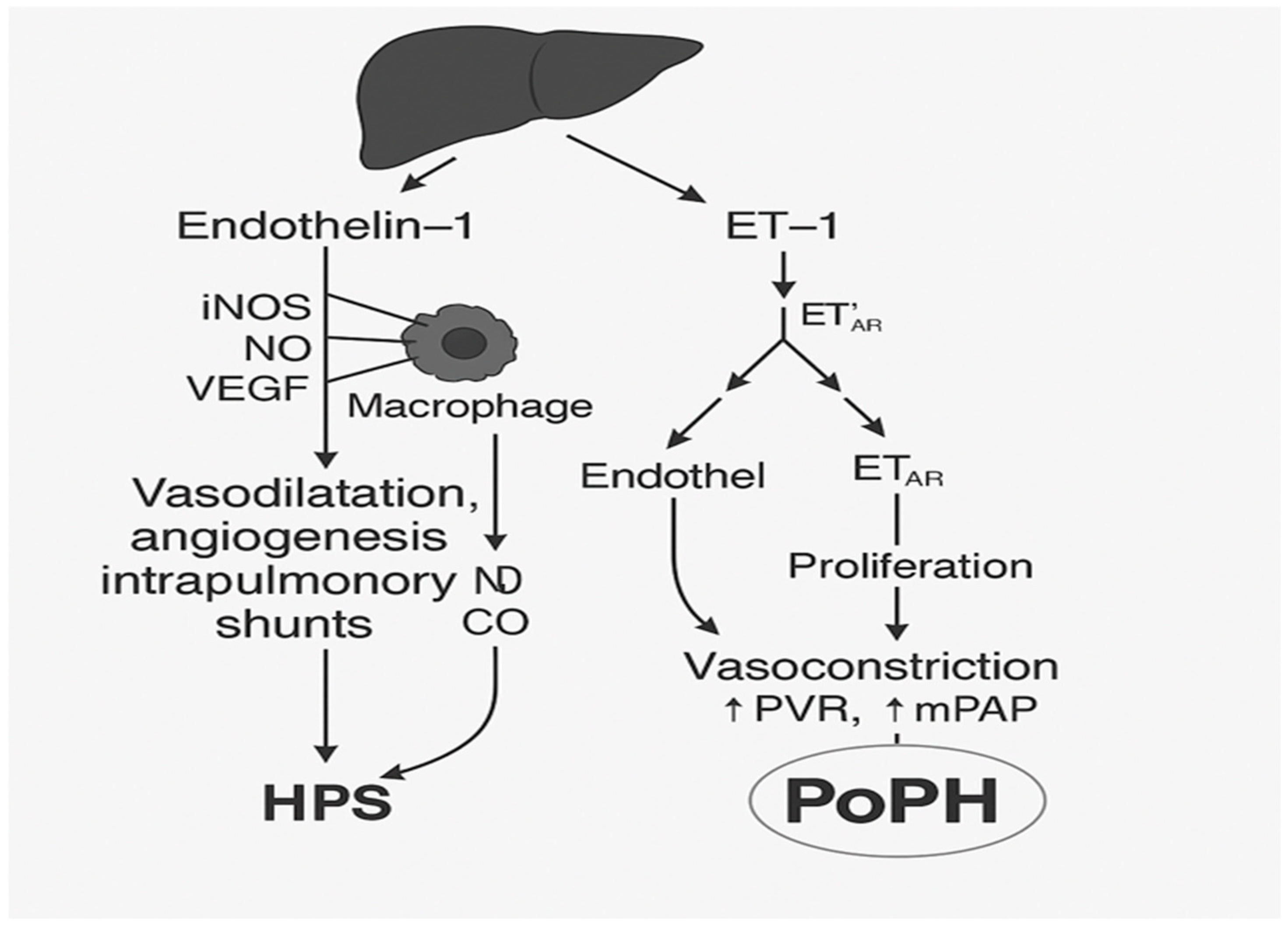

1.2. The Pathophysiology of Portopulmonary Hypertension and Hepatopulmonary Syndrome

2. Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Approach

- -

- mPAP > 20 mmHg;

- -

- PVR ≥ 2 Wood units;

- -

- PAWP ≤ 15 mmHg, excluding postcapillary PH.

- -

- Mild: mPAP 20–35 mmHg, PVR < 3 WU;

- -

- Moderate: 35–50 mmHg, PVR 3–5 WU;

- -

- Severe: mPAP > 50 mmHg, PVR > 5 WU.

- -

- -

- Chronic liver disease with portal hypertension;

- Arterial hypoxemia: PaO2 < 80 mmHg or elevated A—a gradient;

- Proof of intrapulmonary vasodilation, usually via contrast-enhanced echocardiography (microbubble test);

- Exclusion of alternative causes of hypoxemia.

- -

- Mild: PaO2 > 80 mmHg;

- -

- Moderate: 60–79 mmHg;

- -

- Severe: 50–59 mmHg;

- -

- Very severe: PaO2 < 50 mmHg.

3. Results and Treatment

3.1. Therapeutic Implications

3.2. Implications for Clinical Practice

3.2.1. Treatment of Portopulmonary Hypertension

- -

- Endothelin receptor antagonists (ERA);

- -

- Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDE-5i);

- -

- Prostacyclin analogs and agonists;

- -

- Soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulators.

3.2.2. Treatment of Hepatopulmonary Syndrome

3.3. Liver Transplantation and Outcomes

3.3.1. Hepatopulmonary Syndrome

3.3.2. Registry Data

3.4. Clinical Challenges and Implications

- -

- Precise hemodynamic monitoring;

- -

- Timely application of inhalational vasodilators, such as nitric oxide or prostacyclin;

- -

- Careful titration of inotropic drugs and vasopressors.

3.5. Case Examples

3.5.1. Case Example 1

3.5.2. Case Example 2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PoPH | Portopulmonary hypertension |

| HPS | Hepatopulmonary syndrome |

| ETA | Endothelin A |

| ETB | Endothelin B |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

References

- Krowka, M.J.; Miller, D.P.; Barst, R.J.; Dweik, R.A.; Badesch, D.B.; McGoon, M.D.; Taichman, D. Portopulmonary hypertension: A report from the US-based REVEAL registry. Chest 2012, 141, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawut, S.M.; Krowka, M.J.; Trotter, J.F.; Roberts, K.E.; Benza, R.L.; Badesch, D.B.; Taichman, D.B.; Horn, E.M.; Zacks, S.; Kaplowitz, N.; et al. Clinical risk factors for portopulmonary hypertension. Hepatology 2008, 48, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeper, M.M.; Krowka, M.J.; Strassburg, C.P. Portopulmonary hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome. Lancet 2004, 363, 1461–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Roisin, R.; Krowka, M.J.; Hervé, P.; Fallon, M.B. Pulmonary–hepatic vascular disorders (PHD). J. Hepatol. 2004, 41, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, M.B.; Zhang, J.; Luo, B. Hepatopulmonary syndrome: New insights into pathogenesis and clinical features. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 539–548. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Fallon, M.B. Hepatopulmonary syndrome: Update on pathogenesis and clinical features. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 9, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Roisin, R.; Krowka, M.J. Hepatopulmonary syndrome—Clinical features and diagnostic approach. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2378–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, M.B.; Krowka, M.J.; Brown, R.S., Jr.; Trotter, J.F.; Zacks, S.; Roberts, K.E.; Shah, V.H.; Kaplowitz, N.; Forman, L.; Wille, K.; et al. Impact of Hepatopulmonary Syndrome on Quality of Life and Survival in Liver Transplant Candidates. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1168–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Goyal, N.; Pyrrosopoulos, N. Portopulmonary hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome: Implications for liver transplantation. Clin. Liver Dis. 2021, 25, 357–378. [Google Scholar]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitbon, O.; Bosch, J.; Cottreel, E.; Csonka, D.; Groote, P.d.; Hoeper, M.M.; Kim, N.H.; Martin, N.; Savale, L.; Krowka, M. Macitentan for portopulmonary hypertension (PORTICO): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savale, L.; Guimas, M.; Ebstein, N.; Fertin, M.; Jevnikar, M.; Renard, S.; Horeau-Langlard, D.; Tromeur, C.; Chabanne, C.; Prevot, G.; et al. Portopulmonary hypertension in the current era of pulmonary hypertension management. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, P.; Lebrec, D.; Brenot, F.; Simonneau, G.; Humbert, M.; Sitbon, O.; Duroux, P. Pulmonary vascular disorders in portal hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 1998, 11, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, M.B.; Abrams, G.A. Pulmonary dysfunction in chronic liver disease. Hepatology 2000, 32, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Liver Transplantation Society (ILTS) Consensus Group. Consensus recommendations on the evaluation and management of portopulmonary hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome in liver transplantation candidates. Transplantation 2024, 108, e123–e136. [Google Scholar]

- Arguedas, M.R.; Abrams, G.A.; Krowka, M.J.; Fallon, M.B. Prospective evaluation of outcomes and predictors of mortality in patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome undergoing liver transplantation. Hepatology 2003, 37, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, G.A.; Jaffe, C.C.; Hoffer, P.B.; Binder, H.J.; Fallon, M.B. Diagnostic utility of contrast echocardiography and lung perfusion scan in patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome. Gastroenterology 1995, 109, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krowka, M.J.; Mandell, S.M.; Ramsay, M.A.; Kawut, S.M.; Fallon, M.B.; Manzarbeitia, C.; Pardo, M.; Marotta, P.; Uemoto, S.; Stoffel, M.P.; et al. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: A report of the multicenter liver transplant database. Liver Transplant. 2004, 10, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raevens, S.; Rogiers, X.; Geerts, A.; Verhelst, X.; Samuel, U.; van Rosmalen, M.; Berlakovich, G.; Delwaide, J.; Detry, O.; Lehner, F.; et al. Outcome of liver transplantation for hepatopulmonary syndrome: A Eurotransplant experience. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.S.; Krok, K.; Batra, S.; Trotter, J.F.; Kawut, S.M.; Fallon, M.B. Impact of the hepatopulmonary syndrome MELD exception policy on outcomes of patients after liver transplantation: An analysis of the UNOS database. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1256–1265.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadengue, A.; Benhayoun, M.K.; Lebrec, D.; Benhamou, J.P. Pulmonary hypertension complicating portal hypertension: Prevalence and relation to splanchnic hemodynamics. Gastroenterology 1991, 100, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.L.; Wiesner, R.H.; Nyberg, S.L.; Rosen, C.B.; Krowka, M.J. Survival in Portopulmonary Hypertension: Mayo Clinic Experience Categorized by Treatment Subgroups. Am. J. Transplant. 2008, 8, 2445–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, M.H.; Kwon, Y.; Kobierski, P.; Misra, A.C.; Lim, A.; Goldbeck, C.; Etesami, K.; Kohli, R.; Emamaullee, J. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease/Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease exception policy and outcomes in pediatric patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome requiring liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2023, 29, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machicao, V.I.; Fallon, M.B. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: Current status and implications for liver transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2012, 17, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Porres-Aguilar, M.; Duarte-Rojo, A.; Torre-Delgadillo, A.; Charlton, M.R.; Altamirano, J.T. Portopulmonary hypertension: A clinician-oriented review. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2012, 21, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiè, N.; Channick, R.N.; Frantz, R.P.; Grünig, E.; Jing, Z.C.; Moiseeva, O.; Preston, I.R.; Pulido, T.; Safdar, Z.; Tamura, Y.; et al. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, D51–D58. [Google Scholar]

- Simonneau, G.; Montani, D.; Celermajer, D.S.; Denton, C.P.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Krowka, M.; Williams, P.G.; Souza, R. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, M.B.; Zhang, J.; Luo, B. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and oxidative stress: Therapeutic implications. Semin. Liver Dis. 2012, 32, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Krowka, M.J.; Wiesner, R.H. Pulmonary complications of liver disease. Clin. Chest Med. 1996, 17, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeper, M.M.; Rabe, K.F.; Wilkens, H. Characteristics of pulmonary hypertension in patients with chronic liver disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 3, 918–925. [Google Scholar]

| Population | PoPH (%) | HPS (%) | Source/Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| General population with portal hypertension | 2–5 | 10–30 | PoPH is rare, HPS is a more frequent complication |

| Liver transplant candidates | 5–10 | 15–20 (up to 30) | Key group, since these entities affect transplantability |

| UNOS database (USA) | ~5 among recipients | 5–10 among recipients | HPS candidates receive MELD exceptions |

| Eurotransplant data | <5 | ~6 of all indications | Data from multicenter registries |

| Multicenter studies | — | 10–20 of listed candidates | High-risk group with progressive hypoxemia |

| Condition | Mandatory Criteria | Key Investigations | Thresholds/Findings | (Optional) Shunt Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PoPH | Portal hypertension (with or without cirrhosis) | Right-heart catheterization; Echocardiography. | mPAP > 20 mmHg; PVR ≥ 2 Wood units; PAWP ≤ 15 mmHg; Elevated RVSP or RV strain. | — |

| HPS | Chronic liver disease + portal hypertension | Arterial blood gas analysis; Contrast-enhanced transthoracic echocardiography (microbubble test). | PaO2 < 80 mmHg or A–a gradient ≥ 15 mmHg (≥20 mmHg if >64 y); Delayed microbubbles in left atrium (3–6 cardiac cycles). | 99mTc-MAA scan: extrapulmonary uptake > 6% |

| Condition | Therapy Class | Agents | Effects/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PoPH | 1. Endothelin receptor antagonists | Macitentan (first-line, PORTICO trial, Lancet Respir Med 2019), Bosentan, Ambrisentan | ↓ mPAP, improved RV function and tolerance; possible hepatotoxicity and drug interactions |

| 2. Prostacyclin analogs | Epoprostenol, Iloprost, Treprostinil | ↓ PVR, improved RV function; complex delivery, risk of hypotension | |

| 3. PDE-5 inhibitors | Sildenafil, Tadalafil | ↓ mPAP, improved exercise tolerance; pulmonary hypotension, limited data | |

| HPS | Oxygen therapy | Supplemental O2 | ↑ PaO2, symptomatic relief; no effect on disease course |

| Experimental therapies | NO inhibitors, somatostatin, steroids | Tested in small studies; no proven benefit |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Silić, V.; Pavlović, D.B.; Džubur, F.; Romić, I.; Petrović, I.; Pavlek, G.; Zedelj, J.; Redžepi, G.; Samaržija, M. Portopulmonary Hypertension and Hepatopulmonary Syndrome: Contrasting Pathophysiology and Implications for Liver Transplantation. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010072

Silić V, Pavlović DB, Džubur F, Romić I, Petrović I, Pavlek G, Zedelj J, Redžepi G, Samaržija M. Portopulmonary Hypertension and Hepatopulmonary Syndrome: Contrasting Pathophysiology and Implications for Liver Transplantation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilić, Vanja, Daniela Bandić Pavlović, Feđa Džubur, Ivan Romić, Igor Petrović, Goran Pavlek, Jurica Zedelj, Gzim Redžepi, and Miroslav Samaržija. 2026. "Portopulmonary Hypertension and Hepatopulmonary Syndrome: Contrasting Pathophysiology and Implications for Liver Transplantation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010072

APA StyleSilić, V., Pavlović, D. B., Džubur, F., Romić, I., Petrović, I., Pavlek, G., Zedelj, J., Redžepi, G., & Samaržija, M. (2026). Portopulmonary Hypertension and Hepatopulmonary Syndrome: Contrasting Pathophysiology and Implications for Liver Transplantation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010072