Left Atrial Thrombus and Cardioembolic Stroke in Chagas Cardiomyopathy Presenting with Atrial Flutter: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Case Report

3.1. Diagnostic Approach

3.2. Therapeutic Intervention

3.3. Clinical Follow-Up and Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CGS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| mRS | modified Rankin Scale |

| AHA/ASA | American Heart Association/American Stroke Association |

| ASPECTS | Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score |

| NIHSS | National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| ACM | Middle Cerebral Artery |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

References

- Winters, R.; Nguyen, T.; Waseem, M. Chagas Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Vásconez-González, J.; Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S.; Fernandez-Naranjo, R.; Gamez-Rivera, E.; Tello-De-la-Torre, A.; Guerrero-Castillo, G.S.; Ruiz-Sosa, C.; Ortiz-Prado, E. Severe Chagas Disease in Ecuador: A Countrywide Geodemographic Epidemiological Analysis from 2011 to 2021. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1172955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organizacion Mundial de la Salud Enfermedad de Chagas (Tripanosomiasis Americana). Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis) (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Cucunubá, Z.M.; Gutiérrez-Romero, S.A.; Ramírez, J.-D.; Velásquez-Ortiz, N.; Ceccarelli, S.; Parra-Henao, G.; Henao-Martínez, A.F.; Rabinovich, J.; Basáñez, M.-G.; Nouvellet, P.; et al. The Epidemiology of Chagas Disease in the Americas. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2024, 37, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, C.; Nolder, D.; García-Mingo, A.; Moore, D.A.J.; Chiodini, P.L. Diagnosis and Clinical Management of Chagas Disease: An Increasing Challenge in Non-Endemic Areas. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 2022, 13, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swett, M.C.; Rayes, D.L.; Campos, S.V.; Kumar, R.N. Chagas Disease: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2024, 26, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S.; Vásconez-Gonzáles, J.; Morales-Lapo, E.; Tello-De-la-Torre, A.; Naranjo-Lara, P.; Fernández, R.; Hidalgo, M.R.; Escobar, A.; Yépez, V.H.; Díaz, A.M.; et al. Beyond the Acute Phase: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Long-Term Sequelae Resulting from Infectious Diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1293782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lage, T.A.R.; Tupinambás, J.T.; de Pádua, L.B.; Ferreira, M.d.O.; Ferreira, A.C.; Teixeira, A.L.; Nunes, M.C.P. Stroke in Chagas Disease: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Practice. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2022, 55, e0575-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CARE CARE Case Report Guidelines. Available online: https://www.care-statement.org (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Rojas, L.Z.; Glisic, M.; Pletsch-Borba, L.; Echeverría, L.E.; Bramer, W.M.; Bano, A.; Stringa, N.; Zaciragic, A.; Kraja, B.; Asllanaj, E.; et al. Electrocardiographic Abnormalities in Chagas Disease in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathburn, C.M.; Mun, K.T.; Sharma, L.K.; Saver, J.L. TOAST Stroke Subtype Classification in Clinical Practice: Implications for the Get with The Guidelines-Stroke Nationwide Registry. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1375547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, R.L.; Adams, R.; Albers, G.; Alberts, M.J.; Benavente, O.; Furie, K.; Goldstein, L.B.; Gorelick, P.; Halperin, J.; Harbaugh, R.; et al. Guidelines for Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: Co-Sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: The American Academy of Neurology Affirms the Value of This Guideline. Stroke 2006, 37, 577–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, W.J.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Ackerson, T.; Adeoye, O.M.; Bambakidis, N.C.; Becker, K.; Biller, J.; Brown, M.; Demaerschalk, B.M.; Hoh, B.; et al. 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2018, 49, e46–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.C.P.; Kreuser, L.J.; Ribeiro, A.L.; Sousa, G.R.; Costa, H.S.; Botoni, F.A.; Souza, A.C.d.; Marques, V.E.G.; Fernandez, A.B.; Teixeira, A.L.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Embolic Cerebrovascular Events Associated with Chagas Heart Disease. Glob. Heart 2015, 10, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, M.C.P.; Beaton, A.; Acquatella, H.; Bern, C.; Bolger, A.F.; Echeverría, L.E.; Dutra, W.O.; Gascon, J.; Morillo, C.A.; Oliveira-Filho, J.; et al. Chagas Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Current Clinical Knowledge and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 138, e169–e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásconez-González, J.; Miño, C.; Salazar-Santoliva, C.; Villavicencio-Gomezjurado, M.; Ortiz-Prado, E. Chagas Disease as an Underrecognized Cause of Stroke: Implications for Public Health. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1473425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabuco, C.C.; Pereira de Jesus, P.A.; Bacellar, A.S.; Oliveira-Filho, J. Successful Thrombolysis in Cardioembolic Stroke from Chagas Disease. Neurology 2005, 64, 170–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carod-Artal, F.J.; Gascon, J. Chagas Disease and Stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli-Filho, M.; Marin-Neto, J.A.; Scanavacca, M.I.; de Paola, A.A.V.; Medeiros, P.d.T.J.; Owen, R.; Pocock, S.J.; de Siqueira, S.F.; CHAGASICS investigators. Amiodarone or Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator in Chagas Cardiomyopathy: The CHAGASICS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, C.; Migliavaca, C.B.; Colpani, V.; da Rosa, P.R.; Sganzerla, D.; Giordani, N.E.; Miguel, S.R.P.d.S.; Cruz, L.N.; Polanczyk, C.A.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; et al. Amiodarone for Arrhythmia in Patients with Chagas Disease: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khatib, S.M.; Stevenson, W.G.; Ackerman, M.J.; Bryant, W.J.; Callans, D.J.; Curtis, A.B.; Deal, B.J.; Dickfeld, T.; Field, M.E.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death. Circulation 2018, 138, e272–e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, D.O.; Towfighi, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Cockroft, K.M.; Gutierrez, J.; Lombardi-Hill, D.; Kamel, H.; Kernan, W.N.; Kittner, S.J.; Leira, E.C.; et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021, 52, e364–e467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassi, A.; Marin-Neto, J.A. Chagas Disease. Lancet 2010, 375, 1388–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, R.; da Matta, J.A.M.; Mota, G.; Gomes, I.; Melo, A. Cerebral Infarction in Autopsies of Chagasic Patients with Heart Failure. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2003, 81, 414–416, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira-Silva, T.; Gonçalves, B.M.; Pereira, C.B.; Porto, L.M.; Marques, M.E.; Santos, L.S.; Oliveira, M.A.; Félix, I.F.; de Sousa, P.R.P.; Muiños, P.J.; et al. Chagas Disease Is an Independent Predictor of Stroke and Death in a Cohort of Heart Failure Patients. Int. J. Stroke 2022, 17, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Filho, J. Stroke and Brain Atrophy in Chronic Chagas Disease Patients: A New Theory Proposition. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2009, 3, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásconez-González, J.; Miño, C.; Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S.; Salazar-Santoliva, C.; López-Cortés, A.; Ortiz-Prado, E. Cardioembolic Stroke in Chagas Disease: Unraveling the Underexplored Connection through a Systematic Review. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2024, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, P.M.M.; de Andrade, C.M.; Nunes, D.F.; de Sena Pereira, N.; Queiroga, T.B.D.; Machado-Coelho, G.L.L.; Nascimento, M.S.L.; Do-Valle-Matta, M.A.; da Câmara, A.C.J.; Chiari, E.; et al. Inflammation Enhances the Risks of Stroke and Death in Chronic Chagas Disease Patients. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinajá, D.; Aché, A. Alteraciones Electrocardiográficas en pacientes con Enfermedad de Chagas. Hospital José Rangel de Villa de Cura. 1998–2008. Rev. Inst. Nac. Hig. Rafael Rangel 2012, 43, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gula, L.J.; Redfearn, D.P.; Jenkyn, K.B.; Allen, B.; Skanes, A.C.; Leong-Sit, P.; Shariff, S.Z. Elevated Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke in Patients with Atrial Flutter-A Population-Based Study. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018, 34, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, B. Atrial Flutter—Cardiovascular Disorders. Available online: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/cardiovascular-disorders/specific-cardiac-arrhythmias/atrial-flutter (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Rassi, A.; Marin, J.A.; Rassi, A. Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy: A Review of the Main Pathogenic Mechanisms and the Efficacy of Aetiological Treatment Following the BENznidazole Evaluation for Interrupting Trypanosomiasis (BENEFIT) Trial. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2017, 112, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, J.C.P.; Ramos, A.N., Jr.; Gontijo, E.D.; Luquetti, A.; Shikanai-Yasuda, M.A.; Coura, J.R.; Torres, R.M.; Melo, J.R.d.C.; Almeida, E.A.d.; Oliveira, W.d., Jr.; et al. II Consenso Brasileiro em Doença de Chagas, 2015. Epidemiol. E Serviços Saúde 2016, 25, 7–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasslocher-Moreno, A.M.; Saraiva, R.M.; Sangenis, L.H.C.; Xavier, S.S.; de Sousa, A.S.; Costa, A.R.; de Holanda, M.T.; Veloso, H.H.; Mendes, F.S.N.S.; Costa, F.A.C.; et al. Benznidazole Decreases the Risk of Chronic Chagas Disease Progression and Cardiovascular Events: A Long-Term Follow up Study. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 31, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón, J.; Albajar, P.; Cañas, E.; Flores, M.; Gómez i Prat, J.; Herrera, R.N.; Lafuente, C.A.; Luciardi, H.L.; Moncayo, Á.; Molina, L.; et al. Diagnóstico, manejo y tratamiento de la cardiopatía chagásica crónica en áreas donde la infección por Trypanosoma cruzi no es endémica. Enfermedades Infecc. Microbiol. Clínica 2008, 26, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.S.d.; Xavier, S.S.; Freitas, G.R.d; Hasslocher-Moreno, A. Prevention Strategies of Cardioembolic Ischemic Stroke in Chagas’ Disease. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2008, 91, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, J.M.C.; San-Martin, D.L.; Silva, B.C.G.; Jesus, P.A.P.d.; Oliveira Filho, J. Anticoagulation in Patients with Cardiac Manifestations of Chagas Disease and Cardioembolic Ischemic Stroke. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2018, 76, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carod-Artal, F.J. Stroke: A Neglected Complication of American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ Disease). Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 101, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scale | Assessed Parameters/Relevant Subcomponents | Score Obtained | Total Possible Score | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) | Level of consciousness (1a–1c): 0 | 9 | 0–42 | Moderate neurological deficit |

| Eye movements and visual fields (2–3): 0 | ||||

| Facial palsy (4): 2 (left deviation) | ||||

| left arm motor function (5a): 3 | ||||

| left leg motor function (6a): 3 | ||||

| Language (9): 0 (no aphasia) | ||||

| Dysarthria (10): 1 (mild) | ||||

| Other items (ataxia, sensation, extinction): 0 | ||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) | Eye opening (O): 4 | 11/15 | 3–15 | Preserved consciousness; patient alert and oriented |

| Verbal response (V): 5 | ||||

| Motor response (M): 6 | ||||

| Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) | 0: No symptoms or functional limitations | 0 | 0–6 | Complete baseline functional independence before the event |

| 1: Mild symptoms without significant disability | ||||

| 2–5: Mild to severe disability |

| Time Point | Setting | Key Clinical Events & Findings | Diagnostics | Treatment | Outcome/Trajectory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −10 months | Outpatient | Chronic Chagas disease confirmed (T. cruzi IgG+). No etiologic treatment; irregular follow-up. | Serology | None (etiologic) | — |

| Months pre-admission | Outpatient | Recurrent, self-limited palpitations and mild exertional dyspnea. No known structural heart disease. | — | — | — |

| T0 (symptom onset, at rest) | Community | Sudden oppressive chest pain, severe dyspnea, rapid irregular palpitations, transient loss of consciousness; acute left-sided weakness with dysarthria and facial deviation. | — | — | — |

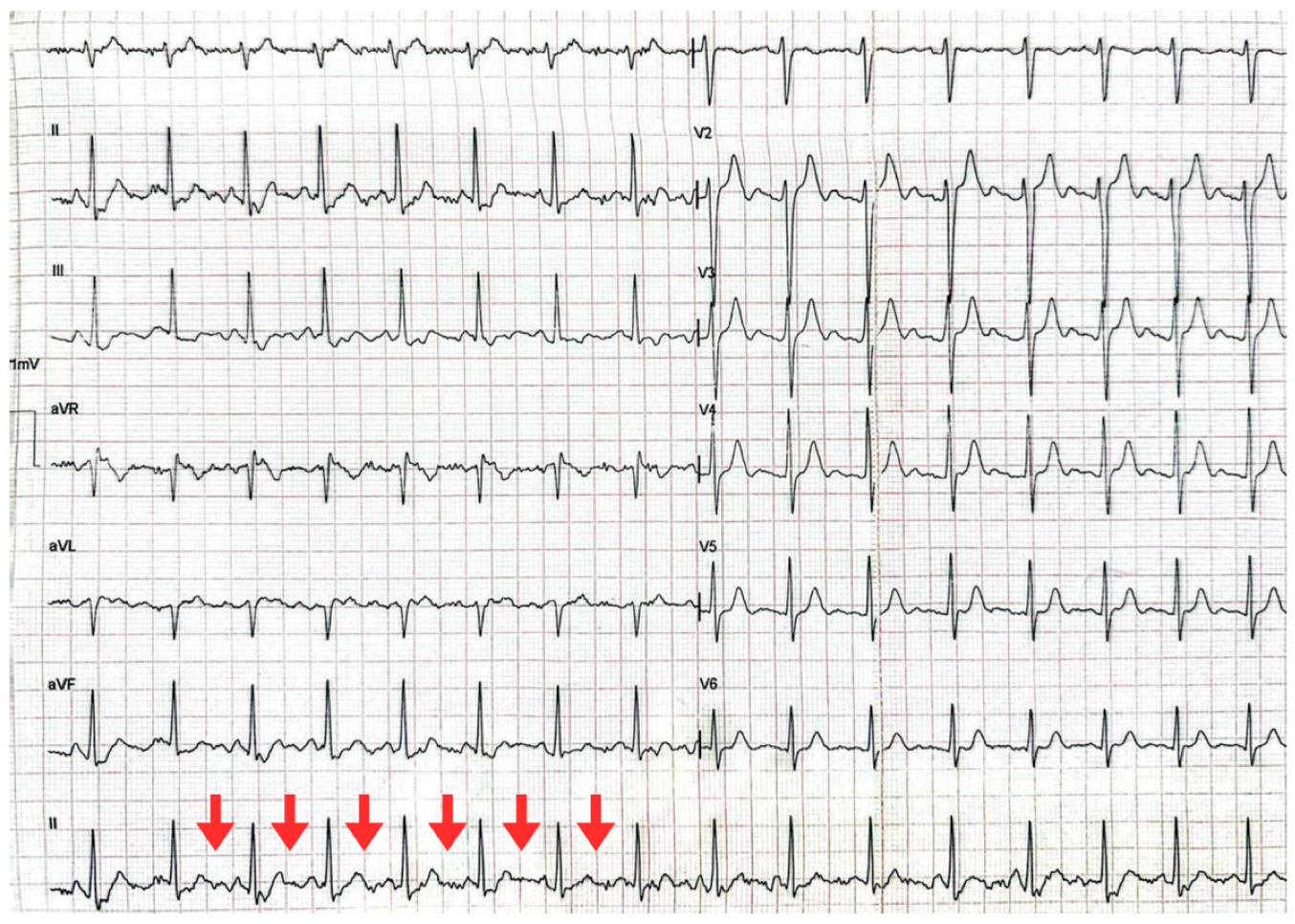

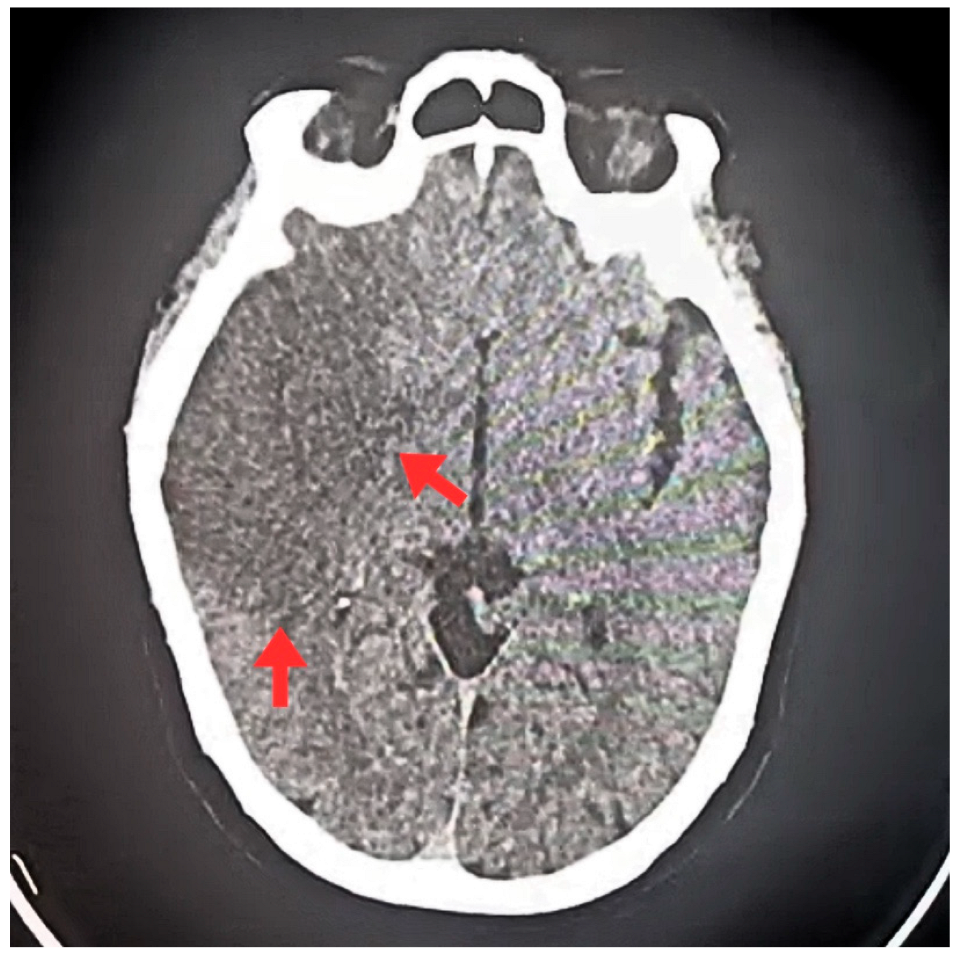

| T0 + ED arrival | Emergency Dept. | Stroke code activated. NIHSS 9, GCS 11/15, premorbid mRS 0. | ECG: typical atrial flutter with rapid ventricular response. Non-contrast CT brain: right MCA ischemic stroke (ASPECTS 7), no hemorrhage. | Supportive acute stroke care | Acute ischemic stroke suspected/confirmed |

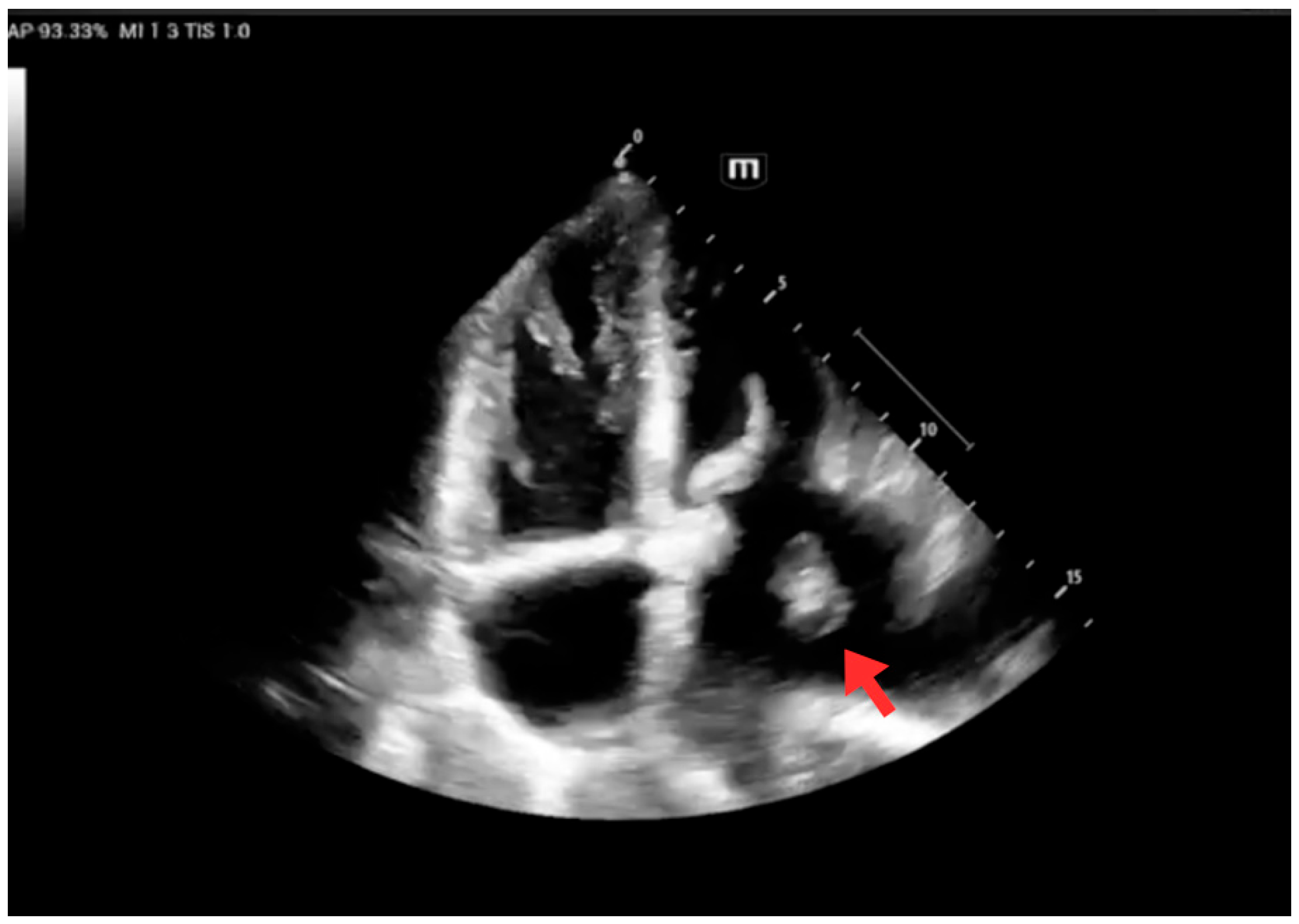

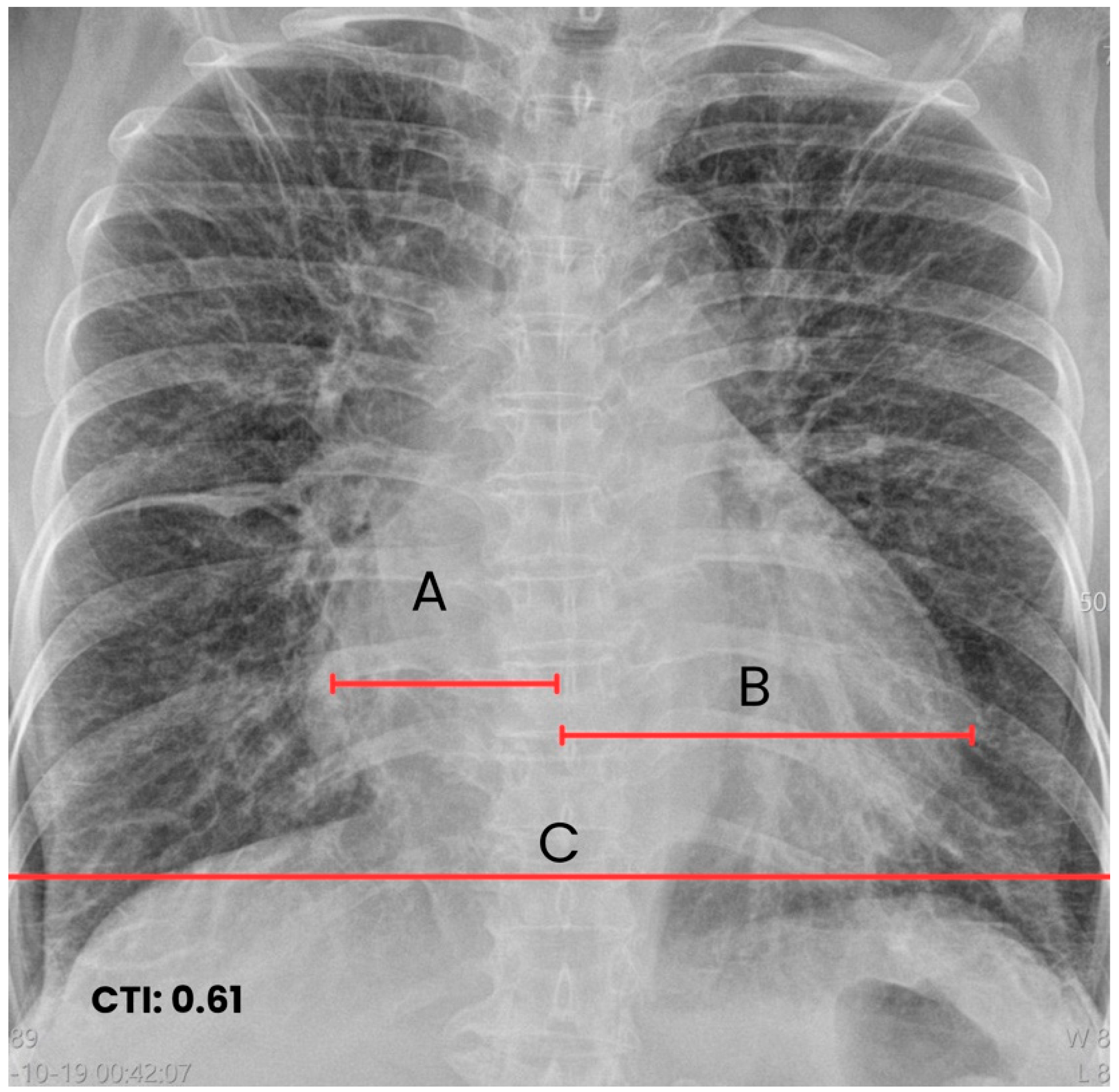

| Early inpatient workup (Day 0) | Hospital | Suspected cardioembolic source in context of arrhythmia/Chagas cardiomyopathy. | TTE: severe LA dilation + mobile LA thrombus; LVEF 45%. Labs: no major abnormalities; mild troponin I and NT-proBNP elevation. | — | Cardioembolic mechanism supported |

| ≤4.5 h from T0 | Hospital | Cardioembolic ischemic stroke diagnosis. | — | IV alteplase (thrombolysis). IV amiodarone for rhythm/rate control. | Stabilization after reperfusion therapy |

| First 24 h | Hospital | Hemodynamic and neurological stability. | Follow-up CT: no hemorrhagic transformation. | Continue monitoring/management | No bleeding complications documented |

| 48 h | Hospital | Marked neurological improvement. | — | — | NIHSS 3; dysarthria resolved; left strength improved (Daniels 4+/5) |

| Hospital course (after hemorrhage exclusion) | Hospital | Secondary prevention initiated. | Risk scores documented: CHA2DS2-VASc 3, HAS-BLED 1. | Warfarin anticoagulation started; transition to oral amiodarone. | Ongoing stability |

| Follow-up echocardiography | Hospital | Persistent LA thrombus, stable/partially organized; no fragmentation signs. | TTE: persistent thrombus; LVEF 48%. | Continue anticoagulation + rhythm control | Thrombus stable; preserved LV function |

| Day 7 (discharge) | Discharge | Clinically stable, minimal deficits. | — | Discharged on oral anticoagulation + rhythm control; outpatient follow-up scheduled. | NIHSS 2, mRS 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moreno-Bejarano, M.S.; Silva-Patiño, I.; Aragón-Jácome, A.C.; Aguilar, J.E.; Cepeda-Zaldumbide, A.S.; Velez-Reyes, A.; Salazar-Santoliva, C.; Vasconez-Gonzalez, J.; Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S.; Ortiz-Prado, E. Left Atrial Thrombus and Cardioembolic Stroke in Chagas Cardiomyopathy Presenting with Atrial Flutter: A Case Report. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020456

Moreno-Bejarano MS, Silva-Patiño I, Aragón-Jácome AC, Aguilar JE, Cepeda-Zaldumbide AS, Velez-Reyes A, Salazar-Santoliva C, Vasconez-Gonzalez J, Izquierdo-Condoy JS, Ortiz-Prado E. Left Atrial Thrombus and Cardioembolic Stroke in Chagas Cardiomyopathy Presenting with Atrial Flutter: A Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020456

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno-Bejarano, Mauricio Sebastián, Israel Silva-Patiño, Andrea Cristina Aragón-Jácome, Juan Esteban Aguilar, Ana Sofía Cepeda-Zaldumbide, Angela Velez-Reyes, Camila Salazar-Santoliva, Jorge Vasconez-Gonzalez, Juan S. Izquierdo-Condoy, and Esteban Ortiz-Prado. 2026. "Left Atrial Thrombus and Cardioembolic Stroke in Chagas Cardiomyopathy Presenting with Atrial Flutter: A Case Report" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020456

APA StyleMoreno-Bejarano, M. S., Silva-Patiño, I., Aragón-Jácome, A. C., Aguilar, J. E., Cepeda-Zaldumbide, A. S., Velez-Reyes, A., Salazar-Santoliva, C., Vasconez-Gonzalez, J., Izquierdo-Condoy, J. S., & Ortiz-Prado, E. (2026). Left Atrial Thrombus and Cardioembolic Stroke in Chagas Cardiomyopathy Presenting with Atrial Flutter: A Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020456